Abstract

Imbalance between Th1 and Th2 functions is considered to play a key role in the induction and development of several autoimmune diseases, and the correction of that imbalance has led to effective therapies of some experimental pathologies. To examine whether CD4+CD45RChigh (Th1-like) and CD4+CD45RClow (Th2-like) lymphocytes play a role in the pathogenesis of adjuvant arthritis (AA) and in its prevention by anti-CD4 antibody, CD45RC expression on CD4+ T cells was determined in arthritic rats and in animals treated with an anti-CD4 MoAb (W3/25) during the latency period of AA. The phenotype of regional lymph node lymphocytes from arthritic rats in the active phase of the disease was determined by flow cytometry. Peripheral blood lymphocytes from rats treated with W3/25 MoAb were also analysed for 2 weeks after immunotherapy finished. IgG2a and IgG1 isotypes of sera antibodies against the AA-inducing mycobacteria, considered to be associated with Th1 and Th2 responses, respectively, were also determined by ELISA techniques. Fourteen days after arthritis induction, regional lymph nodes presented an increase in CD4+CD45RChigh T cell proportion. Preventive immunotherapy with W3/25 MoAb inhibited the external signs of arthritis and produced a specific decrease in blood CD4+CD45RChigh T cells and a diminution of antibodies against mycobacteria, more marked for IgG2a than for IgG1 isotype. These results indicate a possible role of CD4+CD45RChigh T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of AA, and suggest that the success of anti-CD4 treatment is due to a specific effect on CD4+CD45RChigh T subset that could be associated with a decrease in Th1 activity.

Keywords: anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody, arthritis, CD45RC, immunotherapy, Th1/Th2

INTRODUCTION

Adjuvant arthritis (AA), a model of human rheumatoid arthritis (RA) induced in rats by an intradermal injection of heat-inactivated Mycobacterium butyricum (Mb), has been extensively used to elucidate pathogenic mechanisms and to identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention. AA pathogenesis is believed to depend on T lymphocytes, and treatments with anti-CD4 MoAb have proved successful in both preventing or ameliorating the course of the disease [1,2].

T helper lymphocytes were divided into Th1 and Th2 populations according to their profile of secreted cytokines [3]. Th1 cells produce IFNγ, IL-2 and TNFβ, and are invo1ved in cell-mediated immunity. On the other hand, Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and contribute to the humora1 immune response [4]. It has been demonstrated that imbalances between Th1 and Th2 cytokine production play a key role in the induction and development of several autoimmune diseases, and the correction of that imbalance has led to effective therapies of some experimental pathologies [5–7].

Restricted isoforms of the CD45 (CD45R) are expressed on the surface of T lymphocytes [8]. T helper cells are thus divided into two subsets depending on the expression of a high molecular weight isoform of CD45R (CD45RChigh/CD45RClow in rats) [9]. Functional similarities between species have led to widespread acceptance of the hypothesis that the CD4+CD45Rhigh and the CD4+CD45Rlow T lymphocytes are associated with naive and memory T cells, respectively [10]. However, it has been demonstrated in rats that there is a bi-directional switch between the two subsets [11]. Moreover, functional and cytokine expression studies of CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow T cells allow association of these phenotypes with Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes, respectively. In this sense, CD4+CD45RChigh T cells (Th1-like) are involved in T cell-mediated immune response [9], and express and produce high amounts of IL-2 and IFNγ but little or no IL-4 [12]. CD4+CD45RChigh T cells contribute to the development of both chronic intestinal inflammation [13] and autoimmune diabetes [12]. Moreover, graft rejection is attributed to CD4+CD45RChigh T cells [14] and transference of these T cells into nude rats induces a wasting disease with inflammatory infiltrates into multiple organs [15]. On the other hand, CD4+CD45RClow T cells (Th2-like) contribute to the humoral immune response [9], they produce little or no IL-2 and IFNγ, but express high levels of IL-4, IL-10 and TGFβ [12,16,17]. CD4+CD45RClow T lymphocytes are associated with allograft unresponsiveness induced by donor-specific blood transfusion [16] and are markedly deficient in inducing graft rejection [14]. CD4+CD45RClow T cells suppress the progress of autoimmune diabetes [18], autoimmune thyroiditis [17] and inflammatory bowel disease [19].

To assess whether Th1-like (CD4+CD45RChigh) and Th2-like (CD4+CD45RClow) lymphocytes play a role in the pathogenesis of adjuvant arthritis (AA), the CD45RC expression on CD4+ T cells was determined in regional lymph nodes of AA rats. In the second part of the study, AA was prevented by treatment with an anti-CD4 MoAb, and CD45RC expression on blood CD4+ cells was analysed for 2 weeks after immunotherapy finished. Moreover, the isotype of antibodies against the AA-inducing mycobacteria, considered to be associated with Th1 and Th2 responses, was also determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female Wistar rats (Charles River, Criffa, Barcelona, Spain), weighing 200–220 g, were housed three per cage, with food and water ad libitum. Temperature (20 ± 2°C), humidity (55%) and light cycle (on from 8 h to 20 h) were controlled. Housing conditions were clean but not pathogen free. The animals were allowed 2 weeks to adjust to the housing conditions before the experiments began.

Induction and assessment of AA

Rats were injected intradermally into the tail base with 0·5 mg of heat-killed M. butyricum (Mb) (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) in 0·1 ml of liquid vaseline. Assessment of AA was performed by means of body weight increase and articular arthritic score, which was established by grading each paw from 0 to 4 according to the extent of erythema and oedema of the periarticular tissue (the maximal score per animal was 16). All scoring was performed in a blinded fashion.

Experimental design

Two experiments were carried out. In the first, arthritic and healthy groups were killed on day 14 post-induction and inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were excised. In the second experiment, rats were divided into four groups. One group was treated i.p. with 2 mg of W3/25 anti‐rat CD4 MoAb (mouse IgG1, hybridoma from ECACC, Salisbury, UK) [20] during the latency period of AA, i.e. on day 0, before AA induction and on days 2, 4, 7, 9, 11 and 14 thereafter (AA + W3/25 group). Healthy animals, PBS-treated arthritic rats (AA group) and animals injected with 2 mg of an isotype control MoAb (mouse IgG1, anti‐human CD7, hybridoma 124 1D1 kindly provided by Dr Vilella, Barcelona, Spain) (AA + IgG1 group), were used as negative and positive controls. Antibody vehicle was PBS, and the delivery volume was 2 ml per injection. Dose and treatment protocol were established in previous studies [21].

Cell suspension

In the first experiment, regional lymph node lymphocytes (LNL) were obtained from healthy and 14-day post-induction arthritic rats as described previously [22]. Briefly, inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were pressed together through stainless-steel sieves into RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland, UK) containing 5% FCS (Gibco) in a plastic dish. After washing once in PBS containing 2% FCS and 0·1% NaN3, LNL were ready for immunofluorescence staining.

In the second experiment, on days 14, 21 and 28 post-induction, peripheral blood samples were taken by retro-orbital puncture from healthy, AA, AA + W3/25 and AA + IgG1 rats. Erythrocytes were lysed with NH4Cl and after washing, peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were ready for immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out with the following mouse anti‐rat MoAb obtained from the hybridomes (ECACC, Salisbury, UK): OX19 (anti-CD5) [23], W3/25 (anti-CD4), OX8 (anti-CD8 α chain) [24] and OX22 (anti-CD45RC) [9]. OX19, W3/25 and OX8 MoAb were conjugated to FITC and were used at 1/50 dilution. FITC-labelled rabbit anti‐rat Ig (1/100) (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) were used to label B lymphocytes. OX22 (1/250) was applied in double immunofluorescence staining and therefore PE-labelled goat anti‐mouse IgG (1/80) (Sigma, Alcobendas, Spain) was used as secondary antibody. For each animal, a negative control staining was included using an isotype-matched MoAb (124 1D1).

Viable cells with the forward and side-scatter characteristics of lymphocytes were analysed on a Epics Elite flow cytometer (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, FL, USA). Results are expressed as percentages of stained cells with respect to total lymphocyte population. In order to distinguish CD4+ cells with high and low expression of CD45RC, analysis regions were carefully set on OX22/W3/25 histograms.

Determination of anti-Mb antibodies

Total, IgG2a and IgG1 anti-Mb antibody levels in sera were determined by using an indirect ELISA technique, as described previously [25]. Polystyrene microELISA plates (Nunc Maxisorp, Wiesbaden, Germany) were incubated with a soluble protein fraction of Mb in PBS (3 µg/ml). For total antibody determination, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti‐rat Ig (1/2000) (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) was used. For IgG2a, mouse anti‐rat IgG2a MoAb (1/3200) (MARG2a-1, Serotec, Oxford, UK), followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti‐mouse (Fab-specific) IgG (1/2000) (Sigma) were added. For IgG1, biotin-labelled mouse anti‐rat IgG1 MoAb (1/500) (MARG1–2, Serotec) followed by ExtrAvidin-peroxidase (1/4000) (Sigma) were used. Since standards were not available, several dilutions of pooled sera from arthritic control animals were added to each plate. This pool was arbitrarily assigned 8000 U/ml for total anti-Mb antibodies and 1000 U/ml for both IgG2a and IgG1 anti-Mb antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analysed by means of the Mann–Whitney U-test. To evaluate the relative effect of AA and anti-CD4 treatment on T CD4+ subsets (CD45RChigh and CD45RClow) and on anti-Mb antibodies isotypes (IgG2a and IgG1), the ratio between both subsets and both isotypes was calculated individually. Data from total, IgG2a, IgG1 anti-Mb antibodies and IgG2a/IgG1 anti-Mb antibodies ratio were log-transformed to have a better approximation to normal distribution. In this case comparison between groups was assessed by Student's t-test. All analysis were performed using the StatisticaTM computers package for Windows (Stat Soft®, Tulsa, UK). Significant differences were accepted for P < 0·05.

RESULTS

Arthritis development and anti-CD4 MoAb treatment effect

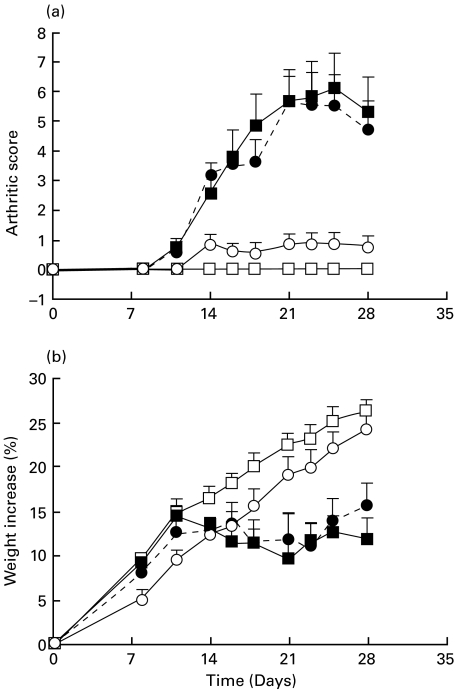

In both experiments, arthritic rats developed a full-blown arthritic syndrome on day 14. In Fig. 1, arthritic scores (a) and body weight increase (b) time-course are shown for the rats of the second experiment. Animals from AA + IgG1 group followed a similar time-course to the AA group throughout the experiment. Treatment with W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb produced significantly lower arthritic scores than those from the AA and AA + IgG1 groups from day 14 until day 28 post-induction (P < 0·01). Moreover, AA + W3/25 group followed a body weight increase similar to that of healthy animals, showing significant differences with both AA and AA + IgG1 groups from day 21 (P < 0·05).

Fig. 1.

Time-course of arthritic score (a) and body weight increase (b) in healthy, arthritic control (AA), arthritic treated with the anti-CD4 MoAb (AA + W3/25) and arthritic treated with control isotype (AA + IgG1) groups. Differences between AA and AA + W3/25 groups are significant for arthritic scores on days 14–28 (P < 0·01) and for body weight increase from day 21 (P < 0·05) (Mann–Whitney U-test). Values are summarized as mean + s.e.m of six rats. □, Healthy; ▪AA; •, AA + IgG1; ○, AA + W3/25.

Main regional LNL populations

On Table 1, percentages of the main lymphocyte populations obtained from healthy and arthritic inguinal and popliteal LN are summarized. After 14 days of induction, the proportion of B and T cells in the LN did not change significantly although a slight increase in B cells was observed. In T cells, there was a significant decrease in CD4+ cell percentage (P < 0·05) and a tendency to increase CD8+ LNL proportion in arthritic animals.

Table 1.

Percentage of regional LNL respect to gated cells. Ratio were individually calculated for each rat. Differences between healthy and arthritic rats are significant for CD4+ cells, CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow subsets and CD4+CD45RChigh/CD4+CD45RClow T cell ratio (P < 0·05) (Mann–Whitney U-test). Results are summarized as mean ± s.e.m. of six rats

| Healthy rats | Arthritic rats | |

|---|---|---|

| CD4+ cells | 58·18 ± 1·22 | 52·94 ± 1·47 |

| CD8+ cells | 16·60 ± 0·81 | 18·13 ± 1·43 |

| CD5+ cells | 74·88 ± 1·32 | 75·65 ± 2·81 |

| B cells | 21·28 ± 1·42 | 24·92 ± 2·38 |

| CD4+ CD45RChigh T cells | 23·65 ± 1·32 | 28·15 ± 1·69 |

| CD4+ CD45RClow T cells | 28·00 ± 1·92 | 17·33 ± 0·97 |

| CD4+CD45RChigh/CD4+CD45RClow T cell ratio | 0·872 ± 0·09 | 1·63 ± 0·07 |

Effect of anti-CD4 MoAb treatment on the main PBL populations

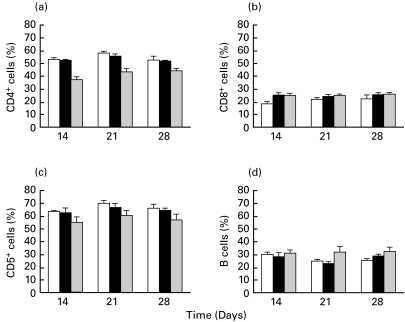

Percentages of blood CD4+, CD8+, CD5+ and B lymphocytes from healthy, AA and AA + W3/25 groups are shown in Fig. 2. Results from AA + IgG1 group were similar to those from AA rats and therefore they are not shown. As can be seen, the induction of AA did not modify, with respect to healthy animals, the percentage of blood CD4+ lymphocytes, which was of about 52–55%. Treatment with W3/25 produced a marked decrease in the percentage of cells with normal expression of CD4 respect to both healthy and AA control groups on days 14–28 (P < 0·05), showing the lowest values on day 14 (end of the treatment). Induction of AA produced higher CD8+ percentage, with respect to healthy values, showing significant differences on day 14 (P < 0·05) (Fig. 2b). The group AA + W3/25 also presented significantly higher percentages of CD8+ cells with respect to healthy animals on day 14 (P < 0·05).

Fig. 2.

Time-course of percentages of CD4+ (a), CD8+ (b), CD5+ (c) and B (d) lymphocytes in healthy, arthritic control (AA) and arthritic treated with the anti-CD4 MoAb (AA + W3/25). Differences in CD4+ cells between AA + W3/25 group and AA and healthy groups are significant on days 14–28 (P < 0·05). In CD8+ cells there are significant differences on day 14 between AA rats and healthy group, and between AA + W3/25 rats and healthy group (P < 0·05) (Mann–Whitney U-test). Values are summarized as mean + s.e.m of six rats. □, Healthy; ▪, AA;  , AA + W3/25.

, AA + W3/25.

No differences in the percentages of CD5+ lymphocytes were found between healthy and AA control rats throughout the study (Fig. 2c). On the other hand, the group treated with anti-CD4 showed lower percentages of CD5+ cells than the other groups, achieving significant differences on days 14–28 with respect to healthy animals (P < 0·05). Figure 2d shows B lymphocyte percentages. In healthy and arthritic control groups, B cell percentages did not change significantly throughout the study (20–30% of total gated lymphocytes). In AA + W3/25 rats, B cells tended to increase although not significantly.

Expression of CD45RC on CD4+ T cells and effect of W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb treatment

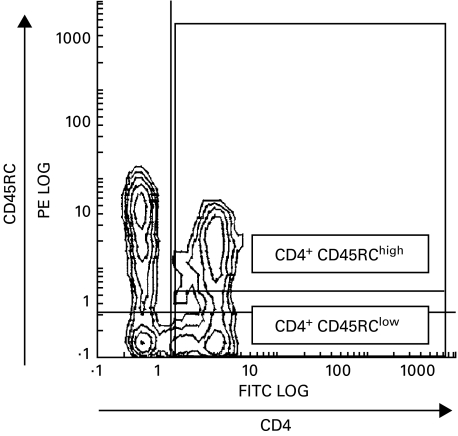

Double staining OX22/W3/25 was performed in order to distinguish the two subpopulations of CD4+ T cells. Threshold between CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow was set after testing several samples of healthy rat lymphocytes. Figure 3 shows the wide rank of CD45RC expression in CD4+ T cells and the gates used to establish high and low expression of CD45RC.

Fig. 3.

Representative histogram of frequency distribution of fluorescence intensity obtained after staining with FITC-anti‐rat CD4 and PE-anti‐rat CD45RC MoAb. Analysis regions set to distinguish CD4+ T cells with high and low expression of CD45RC molecule.

In LNL from healthy rats the ratio between CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow T cells was about 0·87 (Table 1). Fourteen days after induction, arthritic animals showed a higher percentage of CD4+CD45RChigh T cells and lower proportion of CD4+CD45RClow T cells in regional LNL than healthy animals (P < 0·05). Consequently, CD4+CD45RChigh/CD4+CD45RClow T cell ratio in AA rats was significantly higher than that of healthy rats (P < 0·01).

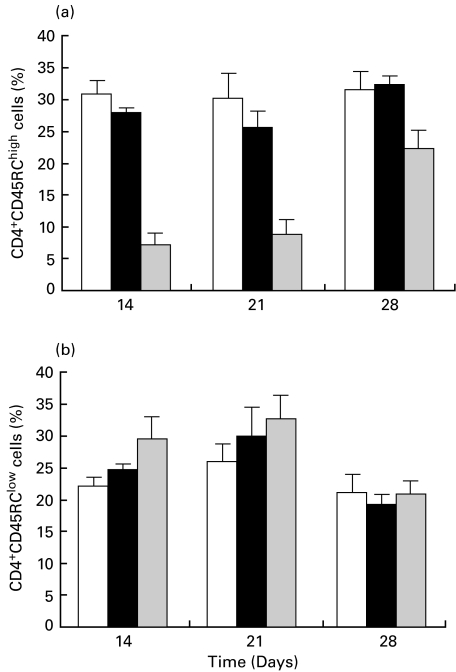

Percentages of blood CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow T lymphocytes from healthy, AA and AA + W3/25 groups are summarized in Fig. 4(AA + IgG1 group showed similar results to the AA group). While the induction of AA did not significantly modify the percentages of the two subpopulations considered, treatment with W3/25 MoAb produced a significant decrease in CD4+CD45RChigh T cells with respect to both healthy and AA groups (P < 0·05). The lowest values were measured on days 14 and 21 and, on day 28, CD4+CD45RChigh T cells tended to recover, although significant differences were still present. The decrease in CD4+CD45RChigh T cells was accompanied by a parallel increase in CD4+CD45RClow T cells, although there were no significant differences (Fig. 4b). In blood the CD4+CD45RChigh/CD4+CD45RClow T cells ratio, which was 1·4 ± 0·23 (mean ± SEM) in healthy rats and 1·1 ± 0·51 in AA animals, fell to 0·24 ± 0·12 and 0·27 ± 0·11 on days 14 and 21, respectively (P < 0·05) in the AA + W3/25 group.

Fig. 4.

Time course of percentages of CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow lymphocytes in healthy, arthritic control (AA) and arthritic treated with the anti-CD4 MoAb (AA + W3/25). Differences in CD4+CD45RChigh cells between AA and AA + W3/25 groups are significant on days 14–28 (P < 0·05) (Mann–Whitney U-test). Values are summarized as mean + s.e.m of six rats. □, Healthy; ▪, AA;  , AA + W3/25.

, AA + W3/25.

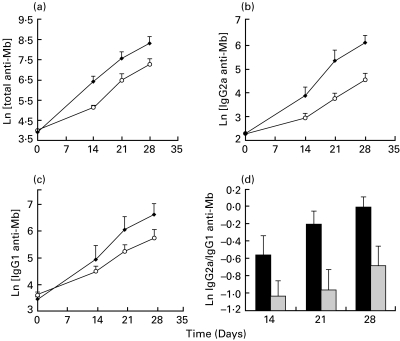

Anti-Mb antibodies and effect of anti-CD4 MoAb treatment

Sera anti-Mb antibody levels from AA control and AA + W3/25 groups are shown in Fig. 5. Values from AA + IgG1 group followed a similar time-course to AA group throughout the study and therefore they are not shown. Absorbances obtained on day 0 were very low and similar among all rats belonging to heatlhy group, AA control, AA + IgG1 and AA + W3/25 groups.

Fig. 5.

Time-course of log-transformed serum anti-Mb antibody levels (a) total; (b) IgG2a; (c) IgG1) developed in AA group (•) and AA + W3/25 group (○). Differences in total and IgG2a anti-Mb levels between log-transformed values of both groups are statistically significant on days 14–28 (P < 0·05) applying a Student's t-test. (d) Time-course of log-transformed IgG2a/IgG1 anti-Mb antibodies ratio in AA group (▪) and AA + W3/25 group ( ). Differences between both groups are significant on days 21 and 28 (P < 0·05) applying a Student's t-test. Values are summarized as mean + s.e.m of six rats.

). Differences between both groups are significant on days 21 and 28 (P < 0·05) applying a Student's t-test. Values are summarized as mean + s.e.m of six rats.

Treatment with anti-CD4 MoAb significantly decreased total anti-Mb antibody levels respect to AA group (P < 0·05). When measuring IgG2a anti-Mb antibodies (Fig. 5b) a significant decrease was also observed in AA + W3/25 rats with respect to the AA group on days 14–28 (P < 0·05). W3/25 treated animals developed lower levels of IgG1 isotype (Fig. 5c), but no significant differences were found with respect to the AA group. IgG2a/IgG1 ratio was calculated individually from rats of AA control and AA + W3/25 groups (Fig. 5d) and significant differences were obtained between means from days 21 and 28 (P < 0·05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, an increase in CD4+CD45RChigh T cell proportion was observed in regional LN of arthritic rats, and a preventive immunotherapy with the W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb, that inhibited the external signs of arthritis, produced a specific decrease in blood CD4+CD45RChigh T lymphocytes and serum antibodies against mycobacteria, more marked for IgG2a than for the IgG1 isotype.

Arthritis produces an inflammatory reaction in synovial membrane that is commonly associated with Th1 activity. Numerous studies have shown an intra-articular predominance of Th1 cell function in RA joints and Th1 cells are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of RA [26,27]. In experimental models of arthritis, an increase in Th1 cytokine pattern has been observed in LN of mice with collagen-induced arthritis [28] and in LN of rats with adjuvant arthritis [29]. Our results concerning CD4+CD45RChigh T lymphocytes in regional LN obtained on day 14, during the active phase of AA, agree with those results. However, the increase in this T helper phenotype was not observed in peripheral blood, where the ratio between CD4+CD45RChigh and CD4+CD45RClow T cells remained unchanged on days 14–28 post-induction. These results could mean that Th1-like phenotype was accumulated in lymphoid tissues draining the joint or in the joint itself, as it has been postulated in RA patients whose Th1 activity did not increase in blood [30].

On the other hand, a preventive immunotherapy with W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb was carried out in AA. This treatment inhibited the external signs of arthritis, i.e. articular inflammation and lower body weight increase, as seen in previous studies [1]. As described [1], W3/25 MoAb mainly down-regulates CD4 molecule on the lymphocyte surface. In the present study, seven doses of W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb produced, as expected, a reduction in the percentage of cells with normal expression of CD4. However, a certain decrease in CD5+ lymphocyte percentage was also observed, indicating a partial depletion of CD4+ cells. The effect of anti-CD4 MoAb on Th lymphocytes decreased blood CD4+CD45RChigh T cells while CD4+CD45RClow T cell percentage remained even higher than that of healthy and arthritic rats. In consequence, the effect of W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb on rat lymphocytes seems to be specific to Th cells with high expression of CD45RC, i.e. Th1-like cells. A selective effect of anti-CD4 MoAb upon cells with high expression of restricted forms of CD45 has also been described. Thus, anti-CD4 MoAb therapy produces a reduction of CD4+CD45RChigh infiltrating lamina propria cells in a model of colitis in rats [13], and depletes more CD4+CD45RBhigh T cells than CD4+CD45RBlow cells in mice [31]. In addition, treatment with a chimeric anti-CD4 MoAb in RA patients has been associated with a relative loss of CD4+CD45RA+ cells [32].

Serum levels of IgG2a and IgG1 antibodies against mycobacteria, considered to be associated with Th1 and Th2 cytokines, respectively [33], were also quantified. Anti-CD4 treatment caused a significant reduction of total antimycobacteria antibodies. When considering the different isotypes separately, the decrease in IgG2a was higher than that in IgG1 antibodies, thus involving a reduced IgG2a/IgG1 antibody ratio. Therefore, W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb treatment produced a greater decrease in antibodies associated with Th1 response than in Th2-linked antibodies. Similar results were found in collagen-induced arthritis after treatment with anti-CD4 MoAb [5], where a decrease in the levels of anticollagen IgG2a antibodies was detected. Moreover, studies that down-regulate Th1 responses in this arthritis model by collagen pretreatment demonstrate a reduction of IgG2a anticollagen antibodies [6,7].

Anti-CD4 MoAb therapy has proved effective in animal models of rheumatoid arthritis and in some clinical studies. It has been suggested that a switch from Th1 to Th2 response is a mechanism by which anti-CD4 MoAb exert their effect on autoimmune diseases [5,34]. In the present work, the beneficial effect of W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb in preventing adjuvant arthritis could be related to a specific effect on CD4+CD45RChigh cells with Th1 activity. In vitro and in vivo studies agree with this suggestion. Thus, it has been shown in vitro that W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb suppresses IFNγ synthesis and enhances IL-4 and IL-13 production [34]. In collagen-induced arthritis in mice, a decrease in the production of Th1-type cytokines after treatment with a non-depleting anti-CD4 MoAb was described [5]. Moreover, a reduction of blood Th1 cell activity after treatment with a non-depleting anti-CD4 MoAb has been demonstrated in RA patients [35]. The suppression of allograft rejection in the rat by anti-CD4 MoAb was associated with a decrease in Th1 cytokines and maintenance of Th2 production by graft-infiltrating cells [36,37]. In multiple sclerosis patients treated with anti-CD4 MoAb, the immunotherapy seemed to act preferentially on Th1 cells [38]. However, in spite of these lines of evidence, in other studies of anti-CD4 MoAb treatments a reduction of Th1 activity or an increase of Th2 response was not so clear [32,39].

In conclusion, adjuvant arthritis in rats seemed to cause an accumulation of CD4+CD45RChigh T cells, Th1-like phenotype, in regional lymph nodes. A preventive treatment with W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb, which prevented arthritis signs, produced two effects related with the down-regulation of the Th1 response: a decrease in blood CD4+ T cells expressing the CD45RC molecule and a reduction of serum levels of IgG2a anti-Mb antibodies. These results suggest that the success of immunotherapy by means of the W3/25 anti-CD4 MoAb can be due to a specific effect on the CD4+CD45RChigh T cell subset, and that could be associated with a decrease in Th1 activity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya (1998SGR-033).The authors thank the ‘Serveis Científico-Tècnics’ of the University of Barcelona, especially Dr J. Comas, for expert assistance in flow cytometry. The authors also thank Professor Dr Miguel Angel Canela for his advice in statistical analysis. They are also grateful to Francisco José Pérez and Silvia Peñuelas for their great help and Paula Queralt and Rosario González for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pelegrí C, Morante MP, Castellote C, Castell M, Franch A. Administration of a nondepleting anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (W3/25) prevents adjuvant arthritis, even upon rechallenge: parallel administration of a depleting anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (OX8) does not modify the effect of W3/25. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:177–82. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelegrí C, Morante MP, Castellote C, Franch A, Castell M. Treatment with an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody strongly ameliorates established rat adjuvant arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:273–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mossman TR, Coffman RL. Th1 and Th2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Ann Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Constant SL, Bottomly K. Induction of Th1 and Th2, CD4+ T cell responses: the alternative approaches. Ann Rev Immunol. 1997;15:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu CQ, Londei M. Induction of Th2 cytokines and control of collagen-induced arthritis by nondepleting anti-CD4 Abs. J Immunol. 1996;157:2685–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattsson L, Lorentzen JC, Svelander L, Bucht A, Nyman U, Klareskog L, Larsson P. Immunization with alum-collagen II complex suppresses the development of collagen-induced arthritis in rats by deviating the immune response. Scand J Immunol. 1997;46:619–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu CQ, Londei M. Differential activities of immunogenic collagen type II peptides in the induction of nasal tolerance to collagen-induced arthritis. J Autoimmun. 1999;12:35–42. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas ML. The leukocyte common antigen family. Ann Rev Immunol. 1989;7:339–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spickett GP, Brandon MR, Mason DW, Williams AF, Woollet GR. MRC OX-22, a new monoclonal antibody that labels a new subset of T lymphocytes and reacts with the high molecular weight form of the leukocyte-common antigen. J Exp Med. 1983;158:795–810. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackay CR. T-cell memory: the connection between function, phenotype and migration pathways. Immunol Today. 1991;12:189–92. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90051-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarawar SR, Sparshott SM, Sutton P, Yang CP, Hutchinson IV, Bell EB. Rapid re-expression of CD45RC on rat CD4 T cells in vitro correlates with a change in function. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:103–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung YH, Jun HS, Son M, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanism for Kilham rat virus-induced autoimmune diabetes in DR-BB rats. J Immunol. 2000;165:2866–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe M, Hosoda Y, Okamoto S, et al. CD45RChighCD4+ intestinal mucosal lymphocytes infiltrating in the inflamed colonic mucosa of a novel rat colitis model induced by TNB immunization. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:45–55. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang CP, Bell EB. Functional maturation of recent thymic emigrants in the periphery: development of alloreactivity correlates with the cyclic expression of CD45RC isoforms. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2261–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powrie F, Mason D. OX-22high CD4+ T cells induce wasting disease with multiple organs pathology: prevention by the OX-22low subset. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1701–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyanari N, Yamaguchi Y, Matsuno K, et al. Persistent infiltration of CD45RC− CD4+ T cells, Th2-like effector cells, in prolonging hepatic allografts in rats pretreated with a donor-specific blood transfusion. Hepatology. 1997;25:1008–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seddon B, Mason D. Regulatory T cells in the control of autoimmunity: the essential role of transforming growth factor β and interleukin 4 in the prevention of autoimmune thyroiditis in rats by peripheral CD4+CD45RC− cells and CD4+CD8− thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1999;189:279–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saoudi A, Seddon B, Fowell D, Mason D. The thymus contains a high frequency of cells that prevent autoimmune diabetes on transfer into pre-diabetic recipients. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2393–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Menon S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted by CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–62. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White RAH, Mason DW, Williams AF, Galfre G, Milstein C. T-lymphocyte heterogeneity in the rat: separation of functional subpopulations using a monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1978;148:664–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.3.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caballero F, Pelegrí C, Castell M, Franch A, Castellote C. Kinetics of W3/25 anti-rat CD4 monoclonal antibody. Studies on optimal doses and time-related effects. Immunopharmacology. 1998;39:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(98)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez-Palmero M, Pelegrí C, Ferri MJ, Castell M, Franch A, Castellote C. Prevention of adjuvant arthritis by the W3/25 anti‐CD4 monoclonal antibody is associated with a decrease of blood CD4+CD45RChigh T cells. Inflammation. 1999;23:153–65. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dallman MJ, Thomas ML, Green JR. MRC OX-19: a monoclonal antibody that labels rat T lymphocytes and augments in vitro proliferative responses. Eur J Immunol. 1984;14:260–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830140311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brideau RJ, Carter PB, McMaster WR, Mason DW, Williams AF. Two subsets of rat T lymphocytes defined with monoclonal antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 1980;10:609–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830100807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franch A, Cassany S, Castellote C, Castell M. Time course of antibodies against IgG and type II collagen in adjuvant arthritis. Role of mycobacteria administration in antibody production. Immunobiology. 1994;190:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolhain RJEM, van der Heiden AN, ter Haar NT, Breedveld FC, Miltenbrug AMM. Shift toward T lymphocytes with a T helper 1 cytokine-secretion profile in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1961–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miossec P, van den Berg W. Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2105–15. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mauri C, Williams RO, Walmsley M, Feldmann M. Relationship between Th1/Th2 cytokine patterns and the arthritogenic response in collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1511–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt-Weber CB, Pohlers D, Siegling A, et al. Cytokine gene activation in synovial membrane, regional lymph nodes, and spleen during the course of rat adjuvant arthritis. Cell Immunol. 1999;195:53–65. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Roon JAG, Verhoef CM, van Roy JLAM, et al. Decrease in peripheral type 1 over type 2 T cell cytokine production in patients with rheumatoid arthritis correlates with an increase in severity of disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:656–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.11.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice JC, Bucy RP. Differences in the degree of depletion rate of recovery, and the preferential elimination of naive CD4+ T cells by anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (GK1.5) in young and aged mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:6644–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Lubbe P, Breedveld FC, Tak PP, Schantz A, Woody J, Miltenburg AMM. Treatment with a chimeric CD4 monoclonal antibody is associated with a relative loss of CD4+/CD45RA+ cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 1997;10:87–97. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross DJ, Moudgil A, Bagga A, et al. Lung allograft dysfunction correlates with gamma-interferon gene expression in bronchoalveolar lavage. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:627–36. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stumbles P, Mason D. Activation of CD4+ T cells in the presence of a nondepleting monoclonal antibody to CD4 induces a Th2-type response in vitro. J Exp Med. 1995;182:5–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulze-Koops H, Davis LS, Haverty TP, Wacholtz MC, Lipsky PE. Reduction of Th1 cell activity in the peripheral circulation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with a non-depleting humanized monoclonal antibody to CD4. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:2065–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Wasowska B, Papp I, et al. CD4 mAb therapy modulates alloantibody production and intracardiac graft deposition in association with selective inhibition of Th1 lymphokines. J Immunol. 1993;151:5053–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegling A, Lehmann M, Riedel H, et al. A nondepleting anti-rat CD4 monoclonal antibody that suppresses T helper 1-like but not T helper 2-like intragraft lymphokine secretion induces long-term survival of renal allografts. Transplantation. 1994;57:464–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199402150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez E, Racadot E, Bataillard M, et al. Interferon γ, IL‐2, IL‐10, TNFα secretions in multiple sclerosis patients treated with an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. Autoimmunity. 1999;29:87–92. doi: 10.3109/08916939908995377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L, Crowley M, Nguyen A, Lo D. Ability of a nondepleting anti-CD4 antibody to inhibit Th2 responses and allergic lung inflammation is independent of coreceptor function. J Immunol. 1999;163:6557–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]