Abstract

The identification of ricin toxin A-chain (RTA) epitopes and the molecular context in which they are recognized will allow strategies to be devised that prevent/suppress an anti-RTA immune response in patients treated with RTA-based immunotoxins. RTA-specific human T-cell lines and T-cell clones were produced by in vitro priming of PBMC. The T-cell clones used a limited set of Vβ chains (Vβ1, Vβ2 and Vβ8) to recognize RTA epitopes. The use of RTA deletion mutants demonstrated that T-cell lines and T-cell clones from three out of four donors responded to RTA epitopes within the domain D124-Q223, whereas one donor recognized the region I1-D124. The response to RTA peptides of T-cell lines and T-cell clones from two donors allowed the identification of immunogenic segments (D124-G140 and L161-T190) recognized in the context of different HLA-DRB1 alleles (HLA-DRB1*0801, and HLA-DRB1*11011 and B1*03011, respectively). The response to L161-T190 was investigated in greater detail. We found that the HLA-DRB1*03011 allele presents a minimal epitope represented by the sequence I175-Y183 of RTA, whereas the HLA-DRB1*11011 allele presents the minimal epitope M174-I184. RTA peptides and an I175A RTA point mutant allowed us to identify I175 as a crucial residue for the epitope(s) recognized by the two HLA-DRB1 alleles. Failure of T-cell clones to recognize ribosome inactivating proteins (RIPs) showing sequences similar but not identical to RTA further confirmed the role of I175 as a key residue for the epitope recognized in the context of HLA-DRB1*11011/03011 alleles.

Keywords: epitopes, immunotherapy, immunotoxins, ricin, T-cell clones

INTRODUCTION

Cell-selective cytotoxic reagents (immunotoxins, ITs) can be obtained by linking vehicle molecules (e.g. antibodies, ligands, growth factors) to potent enzymatic polypeptide toxins [1]. These pharmacological agents are being evaluated for their potential in the treatment of human diseases such as cancer, autoimmune disorders and GVHD [1].

Injection of ricin toxin A-chain (RTA) or RTA-based ITs in vivo elicits a host immune response directed against the heterologous toxin/ITs introduced. Indeed, following inoculation of whole ricin in both animals and humans, antitoxin antibodies have been detected [2]. Similarly, an immune response to both toxins and vehicle murine antibodies has been demonstrated in several animal models [3–5].

Although RTA-ITs achieved considerable therapeutic responses in phase I-II trials, in most of the studies reported (except those conducted in immunosuppressed patients) anti-ITs antibodies were generated [6–12]. Injection of RTA-ITs in patients resulted in the production of antibodies belonging to the IgG class, indicating that RTA is a T-cell dependent Ag able to induce a secondary immune response [13]. In some cases, these antibodies neutralized the cytotoxic potential of the injected ITs and in most cases reported they decreased the half-life of the ITs in the blood [7–13]. Therefore, anti-RTA antibodies can alter ITs pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and may also precipitate serum sickness or anaphylaxis. Thus, the potential value of RTA-ITs in the treatment of human diseases may be hampered in several ways by the development of host antibodies against the conjugate. The host immune response against the antibody moiety of the ITs could be greatly reduced by using humanized antibodies [14] or cell-selective ligands of human origin (e.g. human EGF or transferrin) [15,16]. However, abrogation of the host immune response against the heterologous toxin RTA would require more complex approaches.

Strategies to prevent or reduce the titre of anti-RTA-ITs antibodies were evaluated in animal models by treating mice with the immunosuppressive drug cyclophosphamide [17], with anti-RTA antibodies [18] or with other immunosuppressants [19]. In these instances a considerable decrease in the antibody response against the ITs was observed. These approaches, however, may not be directly applicable in humans. In fact, in melanoma patients treated with RTA-ITs co-injected with cyclophosphamide no diminution of the antibody response against the RTA-ITs was achieved [20].

In the present paper analysis of the response of human T-cells against RTA following in vitro immunization and identification of the T-cell epitopes of RTA are described for the first time. Identifying the main T-cell-dependent epitopes of RTA and the molecular context in which they are recognized may open the way to specific immunoprevention/immunosuppression strategies that may eventually lead to the abolishment/decrease of RTA immunogenicity in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Chemicals were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) used in cytofluorometry were from Becton-Dickinson. MoAbs to the MHC class II molecules DR, DP and DQ were kindly supplied by Dr R. S. Accolla (University of Insubria, Italy). Native Ricin A-chain purified from the holotoxin by biochemical procedures was obtained from Dr P. Casellas (Sanofi Recherche, Montpellier, France), Prof. F. Stirpe and Prof. L. Barbieri (Dipartimento di Patologia Sperimentale, University of Bologna, Italy) kindly supplied the RIPs-I (dianthin, momordin, saporin, pokeweed antiviral protein-S and gelonin) used herein. Synthetic peptides of RTA were prepared in an Applied Biosystems automated synthesizer by using the solid-phase method originally developed by Merrifield [21]. The purity of the peptides was assessed by HPLC and mass spectrometry and found to be > 90%.

RTA mutants

Deletion mutants

To obtain RTA deletion mutants the RTA gene was cloned into M13mp18 (Boehringer Mannheim) and base changes were introduced by using synthetic oligonucleotides carrying appropriate mutations that resulted in either stop codons (mutants RTA-Δ2 and RTA-Δ3) or in the insertion of BamHI restriction sites (mutants RTA-Δ4, RTA-Δ5 and RTA-Δ6). Mutagenized DNA fragments were then cloned into the pEX34A vector for expression in Escherichia coli [22]. Mutant proteins were purified by lysing the bacteria and collecting the inclusion bodies. Inclusion bodies were then resuspended in 7·0 m urea and following dilution to 1·0 m urea proteins were loaded onto a 12·5% SDS-PAGE [23]. Mutant RTAs were identified in the SDS-PAGE slab by reversible staining with copper stain [24] and electroeluted from the gel. Mutant proteins were then dialysed against PBS and used in proliferation assays as described below.

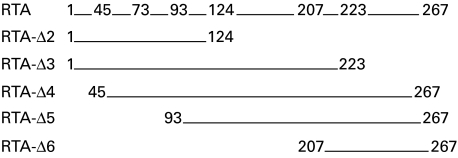

A schematic representation of RTA and its deletion mutants is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the sequence of native RTA and its deletion mutants. Positions identified by numbers represent key amino acids where the RTA sequence has been modified to create the deletion mutants. Amino acid number 1 is the first N-terminal amino acid (I, isoleucin), amino acid 267 (F, phenylalanine) is the last C-terminal amino acid. Superimposed numbers correspond to residues where the RTA mutant ends or to residues where the mutant RTA begins (sequence based on [37]).

Point mutant I175A

The mutant RTA I175A was created by a two-step PCR procedure, as described by Ho et al. [25]. Briefly, two segments of the RTA gene were first PCR-amplified independently and then fused together in a subsequent reaction. The I175→Ala mutation was introduced into the targeted region by the use of mutagenizing primers (TCCTTTATAATATG CATCCAAATGGCTTCAGAAGCA, forward, and TGCTTCTG AAGCCATTTGGATGCATATTATAAAGGA, reverse) containing nucleotide mismatches. The partially overlapping PCR products obtained were then subsequently extended and amplified with the outside primers ATGGGATCCTCTAGAGTCG (forward) and CATGATGCCGGATCCATAC (reverse) to form the final mutant product. Outside primers also introduced a BamHI restriction site at the 5′ and 3′ ends which allowed the cloning of the amplified mutated product into the pDS5/3 expression vector [26]. The I175A RTA mutant was then expressed and purified as described elsewhere [26].

Lymphocyte preparation and T-cell cloning

Blood was obtained from normal volunteers with no history of previous sensitization to RTA and with no evidence of anti-RTA antibodies in their serum, as evaluated by ELISA. PBMC were isolated on Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia). Following three washings with RPMI-1640 (Seromed) PBMC were cultured at a density of 2 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates (Greiner) in complete culture medium [RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% pooled heat-inactivated human AB serum (Sigma), with 2 mm l-glutamine] in the presence of 100 μg heat-denatured native RTA. After incubation for 7 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 athmosphere, 50–100 IU rIL-2 (Chiron) were added and the cells incubated for a further two cycles of stimulation with RTA. Cultures responding to stimulation with RTA were then cloned by limiting dilution by plating 0·3 cell/well in flat-bottomed 96-well culture plates (Costar) in the presence of 105 irradiated (4000 rad) autologous PBMC, 1% PHA (Gibco) and rIL-2. Complete culture medium containing rIL-2 was changed every 4 days until clones began to be visible by light microscopy. Wells positive for cell growth were further expanded and used as a source of cloned T-cells. An estimate of cloning efficiency was obtained by the minimum χ2 method from the Poisson distribution relationship between the number of plated cells and the logarithm of the percentage of wells without cell growth [27].

Proliferation assays

T-cell populations

Non-clonal RTA-stimulated long-term T-cell cultures (T-cell lines) were exposed to RTA in the presence of irradiated autologous PBMC or B-EBV cell lines as APC (see below) and cultured under the same general conditions as described in the previous paragraph. Proliferation was assessed by measuring 3H-TdR incorporation: at the end of the culture period 0·5 μCi of 3H-TdR (Amersham) were added and the cells incubated for a further 16 h. After this time the cells were harvested onto glass fibre filters, washed with water and dried. Radioactivity incorporated by the cells was then measured in a β-spectrometer. Values of cpm obtained from duplicate or triplicate microcultures with < 15% cpm variations were averaged and used to calculate the stimulation index (SI) (cpm of Ag-stimulated cell sample/cpm of unstimulated control mock-treated cell sample). Proliferation was considered significant when SI ≥ 2. Values of 3H-TdR incorporation in the absence of Ag were usually < 200 cpm.

Cloned T-cells

The response of cloned T-cells to RTA or to RIPs-I was assayed following exhaustive washings to eliminate rIL-2 from cell cultures and o.n. incubation in the absence of rIL-2. Two hundred thousand T-cells were then dispensed into each well of a 96-well flat-bottomed microtitre plate in the presence of heat-denatured native RTA, native RIPs-I, RTA deletion mutants (50 μg/ml to 6·5 μg/ml) or of the peptide under study (10–50 μg/ml peptide) and 1 × 105 irradiated autologous PBMC or EBV-immortalized B lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-EBV) (see below). After 3–4 days' culture, proliferation was assayed as described in the previous paragraph. Values of 3H-TdR incorporation by T-cell clones in the absence of Ag were usually < 500 cpm. Results are expressed as SI (see above).

B-lymphoblastoid cell lines

PBMC or T-cell depleted PBMC populations from normal donors were used. PBMC were depleted of T-cells by E-rosetting followed by separation of rosetting and non-rosetting cells by density gradient centrifugation as described by Mingari et al. [28]. B-cell lines were obtained by o.n. incubation of 107 PBMC or T-cell depleted PBMC populations with an EBV-containing supernatant of the marmoset cell line B95-8 (American Tissue Culture Collection). To identify the MHC class II alleles restricting the response of T-cell clones to RTA, the following human EBV transformed homozygous B-cell lines (from the European Collection For Biomedical Research) were used as APC in proliferation assays: JESTHOM (DRB1*0101), BM9 (DRB1*0801), SWEIG (DRB1*11011), WT 49 (DRB1 *03011), VAVY (DRB3*0101).

Flow cytometry

Expression of cell surface markers was evaluated by direct immunofluorescence and flow cytofluorometry as described previously [29]. Briefly, cells were treated with saturating amounts of fluoresceinated and phycoeritrin-labelled MoAbs anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD45RO and anti-CD45RA MoAbs (Becton-Dickinson). Stained cells were then evaluated by two-colour fluorescence analysis on an XL-MCL cytofluorometer (Coulter) with an exciting wavelength of 488 nm at 200 mW power. Controls included isotype-matched fluorochrome-labelled MoAbs.

Inhibition assay with MoAbs

Blocking experiments were performed with partially purified monoclonals directed against HLA-DR, HLA-DP and HLA-DQ MHC class II molecules (MoAbs D1·12, specific for HLA-DR monomorphic determinants; MoAbs B7/21, specific for HLA-DP monomorphic determinants; and a pool of MoAbs BT 3/4, XIII 358·4 and XIV 466·2 specific for epitopes present in the serological specificities HLA-DQ1, -DQ2, and -DQ3, respectively, thus including all known HLA-DQ alleles) [30] obtained by 50% (NH4)2S04 cut of ascitic fluid. Inhibition assays were performed by preincubation of APC (PBMC or B-EBV cell lines) and T-cells with anti-MHC class II MoAbs for 1 h at a final MoAbs concentration of approximately 10 μg/ml. In preliminary experiments this concentration was found to saturate all available sites present on the surface of APC. T-cells were then assayed for proliferation in response to RTA in the presence of autologous APC.

Cytokine expression

The expression of cytokines by individual T-cell clones was investigated by RT-PCR as described by M. Yamamura et al. [31]. Briefly, cells were exposed to PMA (10 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml) for 4 h at 37°C. Cells (4 × 106) were then washed twice in PBS and the cell pellets from equal amounts of cells used as a source of RNA. Total RNA was isolated by the guanidium-isothiocyanate/CsCl gradient method. RT-PCR was performed with the RT-PCR kit by Perkin-Elmer Italia with oligo-dT priming, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Samples were amplified by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min and annealing-extension at 55°C (for IL-2 and IFN-γ) or 65°C (for IL-4) for 2 min using the primers described by M. Yamamura et al. [31] for each relevant cytokine. The β-actin PCR product was used as a standard control to compare the effects of the amplification procedure. PCR products were analysed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

TCR Vβ determination

Total RNA was prepared from 2–4 × 106 cloned T-cells or from T-cell lines using RNAzol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. TCR Vβ chain-specific first strand cDNA was synthesized using 4–8 μg of total RNA and the appropriate constant region specific oligonucleotide primer as described by C. Lunardi et al. [32]. PCR amplification of the V gene segments present in cDNA was performed using 24 Vβ family-specific oligonucleotides as 5′ primers [32,33] and a TCR β constant region oligonucleotide [32] as 3′ primer which were internal to those used for cDNA sytnthesis. PCR was performed for 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C and 1 min at 72°C. Amplification products were then analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

HLA typing

The HLA-DR haplotypes of donors used as a source of PBMC for anti-RTA T-cell clones and APC were determined by PCR and sequence-based typing, essentially as described [34,35]. Nomenclature of HLA-DR alleles is as described in [36].

Cytotoxicity assay

The effects of wild-type or of I175A mutant RTA toxins were compared in protein synthesis inhibition assays. Protein synthesis was assayed by dispensing 5 × 104 Jurkat cells in leucine-free, RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum in 96-well flat-bottomed microtitration plates. Ten-fold dilutions of toxins were then added (final volume of 100 μl, concentration range 10−6 − 10−12 m) in triplicate. Microcultures were incubated for 20 h. After this time, the cells were pulsed for 4 h with 1 μCi of [14C]Leu (314·3 mCi mmol/l; DuPont NEN). At the end of the assay, the cells were harvested onto glass-fibre filters, washed with water and dried. Radioactivity incorporated by the cells was then measured in a β-spectrometer. Radioactivity incorporated by control mock-treated cultures represented 100% of the incorporation.

Data analysis

To directly compare assays performed on different days and with different T-cell clones, the response to RTA mutants or to peptides is expressed as a percentage of the response to whole RTA or to the appropriate internal standards (peptides L161-T190 and C171-E185). The percentage was calculated by considering the SI value obtained with RTA or with other internal standards (see above) as 100% of the response. Unless specified otherwise the data shown represent the average of the responses of different individual T-cell clones and are expressed as mean percentage ± s.e. To facilitate interpretation of the results, SI of cultures stimulated with whole RTA or with other appropriate internal standards are reported in the legends to the Tables.

RESULTS

RTA domains recognized by human T-cell clones

T-cell enriched populations were obtained from PBMC of donors MC, GF, GCA and OP stimulated in vitro with RTA. RTA-specific T-cell lines were then cloned by limiting dilution. The cloning efficiency ranged between 32% and 100%. Of the T-cell clones developed, the percentages of those responding to RTA in a subsequent assay were 62·5% (GF), 100% (MC), 38% (GCA) and 87% (OP), respectively. A total of 170 RTA-reactive T-cell clones were obtained. The T-cell clones showing the greatest proliferative potential were selected for further studies.

To identify the regions of RTA recognized by RTA-specific human T-cells, RTA-reactive T-cell clones from all donors were restimulated with RTA deletion mutants. The pattern of response of representative T-cell clones from donors MC, GF, GCA and OP is shown in Table 1. T-cell clones obtained from MC, GF and GCA recognized predominantly the RTA mutants Δ3, Δ4 and Δ5 (Table 1). Common to these mutants is a region of RTA encompassing aa 124 (D124) through to aa 223 (Q223) (Fig. 1). T-cell clones from donor GF also appeared to recognize a region of RTA comprised of L207-F267 (RTA-Δ6). T-cell clones from donor OP recognized the RTA mutants Δ2 and Δ3 instead, and may therefore be directed against the segment I1-D124.

Table 1.

Proliferative response of T-cell clones to RTA deletion mutants

| Responding T-cell clones | RTA | RTA-Δ2 (I1-D124)* | RTA-Δ3 (I1-Q223) | RTA-Δ4 (L45-F267) | RTA-Δ5 (F93-F267) | RTA-Δ6 (L207-F267) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC† | 100‡ | 3·5 ± 1·6¶ | 112·3 ± 5·5 | 109·8 ± 2·8 | 77·4 ± 4·8 | 0 |

| GF | 100 | 0 | 75·0 ± 12·1 | 95·7 ± 7·6 | 62·2 ± 15·6 | 101·1 ± 10·5 |

| GCA | 100 | 0 | 245 | 232 | 71 | 0 |

| OP | 100 | 72·6 ± 11·4 | 46·8 ± 11·7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Numbers in parenthesis correspond to the first N-terminal and to the last C-terminal amino acid of the sequence of RTA reproduced in the RTA deletion mutant examined, as shown in Fig. 1. Amino acids are identified by the single letter code.

The response of individual T-cell clones of the donors listed is averaged. The number of clones used for each donor is supplied below.

The SI of RTA-stimulated cultures is taken as 100% of the response. The SI of RTA-stimulated cultures was 391·5 ± 35·7 (4 MC clones), 9·3 ± 1·9 (9 GF clones), 3·6 and 14 (2 GCA clones), and 9·3 ± 2·5 (5 OP clones).

Values reported represent the percentage response with respect to cultures stimulated with whole RTA ± s.e.

Human RTA-selective T-cell clones express a limited set of Vβ chains and belong to either the TH0 or the TH1 subtype

RTA-specific T-cell clones and T-cell lines were phenotypically characterized for expression of CD4, CD8, TCR Vβ chains, and the cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-4. Most of the T-cell clones isolated were CD4+ (77–92% CD4+ T-cell clones from donors MC and GCA, 50% from donor GF and 71% from donor OP, in several separate rounds of cloning). One MC T-cell clone (MC 2) expressed both CD4 and CD8 (CD4+/CD8+), whereas T-cell clones obtained from GF and OP were either CD4+ or CD8+.

PCR analysis of the Vβ gene family expression was performed with anti-RTA T-cell lines and clones from donors MC, GF and GCA (Table 2). This investigation revealed that in T-cell lines from GF and GCA all Vβ families were amplified after 2–3 cycles of stimulation. In T-cell lines from donor MC, which were exposed a greater number of times to RTA, only 5 Vβ families could be identified. In T-cell clones from MC and GF a restricted panel of Vβ family amplification was found (Table 2). T-cell clones from donor MC showed a predominant expression of Vβ8, whereas T-cell clones from donor GF showed preferential expression of Vβ2 chains. Two antitetanus toxoid (TT) T-cell clones from donor GF used as controls (GF 6TT and GF 7TT) expressed Vβ14 chains. By contrast, anti-RTA T-cell clones obtained from donor GCA showed a more heterogeneous pattern of Vβ chain expression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Expression of Vβ gene families by anti-RTA T-cells

| Responders | Number of stimulation with Ag | Vβ chains expressed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell lines | GF | 3 | 1–24 |

| GCA | 2 | 1–24 | |

| (3,6,8,13,17)* | |||

| MC | 4 | 1,6,7,8,13 | |

| T-cell clones | MC 2 | 8 | |

| MC 18 | 8 | ||

| MC 55 | 8 | ||

| MC 59 | 8 | ||

| MC 61 | 8 | ||

| MC 65 | 1 | ||

| GF 1 | 1 | ||

| GF 13 | 2 | ||

| GF 27 | 2 | ||

| GF 30 | 2 | ||

| GF 6TT | 14 | ||

| GF 7TT | 14 | ||

| GCA 10 | 14 | ||

| GCA 29 | 6 | ||

| GCA 33 | 13 |

Numbers in parenthesis correspond to Vβ chains showing quantitatively higher expression.

Attribution of the T-cell clones to the TH0, TH1 or TH2 subsets was determined based on the pattern of cytokines produced by the individual T-cell clones assayed, as evaluated by RT-PCR. The following T-cell clones were examined: MC 2, 3, 13, 16, 18, 42, 55, 61 and 65. RTA-specific T-cell clones were maximally stimulated with PMA + ionomycin and the cells were subsequently harvested and processed for RT-PCR analysis of cytokine mRNA transcripts. RT-PCR revealed that MC T-cell clones belonged to either the TH0 or the TH1 subtype. In fact, five out of nine T-cell clones (i.e. clones MC 3, 16, 18, 61 and 65) produced mRNA transcripts of both TH1- and TH2-type cytokines (i.e. IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-4) and four out of nine T-cell clones (i.e. clones MC 2, 13, 42 and 55) produced cytokine transcripts characteristic of the TH1 subtype of T-lymphocytes (i.e. IL-2 and IFN-γ but no IL-4). No TH2 T-cell clones were found.

Anti-RTA responses are restricted by HLA-DR molecules

T-cell clones with a T-helper CD4+ phenotype showed a higher proliferative potential upon stimulation with RTA, RTA deletion mutants and RTA-derived peptides than other phenotypes and were therefore selected for subsequent investigations.

The role of MHC class II molecules on RTA-induced T-cell proliferation was evaluated. Inhibition assays with MoAbs against HLA class II molecules DR, DP and DQ were performed to determine the type of restriction element used in RTA peptide recognition by the CD4+ T-cell clones and lines from the donors considered. T-cell lines and T-cell clones were therefore cultured with autologous PBMC or B-EBV cells as APC, RTA as stimulating Ag, and MoAbs to the HLA class II molecules DR, DP and DQ. As shown in Table 3, anti-DR antibodies showed the greatest inhibitory effect on antigen-induced proliferation (inhibition ranging from 51% to 98·8%). Therefore, these clones appeared to recognize RTA in the context of DR molecules. In a second set of experiments, designed to determine the DR alleles involved in the presentation of RTA epitopes, a panel of allogeneic lymphoblastoid cell lines, homozygous for the MHC class-II molecules expressed by the donors MC and GF, was used to present RTA to anti-RTA non-clonal T-cell populations. Table 4 shows the HLA-DR alleles of donors MC and GF, as evaluated by PCR and sequence-based typing. Table 4 also illustrates the response of T-cell lines from donors MC and GF to challenge with RTA processed and presented by autologous APC, by different homozygous B-EBV cell lines or by unrelated APC. From our results it can be concluded that RTA is recognized by MC T-cells in the context of the HLA-DR alleles DRB1*11011 and DRB1*03011, whereas RTA is recognized by GF T-cells in the context of the HLA-DR allele DRB1*0801.

Table 3.

Inhibition of anti-RTA response by anti MHC class II antibodies in RTA-specific T-cell clones and T-cell lines

| % Inhibition of response to RTA*,† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responders | APC | anti DR | anti DP | anti DQ |

| MC 55 | Autol. PBMC | 59·8 | n.d.‡ | n.d. |

| MC T-cell line | Autol. PBMC | 99·7 | n.d. | n.d. |

| GF 13 | Autol. PBMC | 89·7 | 41 | 0 |

| GF 27 | Autol. PBMC | 67 | 43 | 27 |

| GF 30 | Autol. PBMC | 51 | 20 | 40 |

| GF T-cell line | Autol. PBMC | 99·7 | n.d. | n.d. |

| GF PBMC | Autol. PBMC | 99·8 | n.d. | n.d. |

| GCA 33 | B-EBV | 57·2 | 25·7 | 0 |

Response to RTA was evaluated as 3H-TdR incorporation.

Percentage of inhibition was calculated taking the SI of samples exposed to RTA in the absence of anti-MHC class II antibodies as 100%.

n.d. = not determined.

Table 4.

Response of T-cell lines to RTA epitopes presented by homozygous B-EBV cell lines as APC

| Responders | HLA-DR alleles of responder | APC | HLA-DR alleles of APC | Stimulation index* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC T-cell line | DRB1*03011/11011, | Autol. PBMC | 7 | |

| DRB3*0101 | SWEIG† | DRB1*11011 | 6 | |

| WT 49 | DRB1*03011 | 7·5 | ||

| VAVY | DRB3*0101 | 2·2 | ||

| Unrelated | < 2 | |||

| GF T-cell line | DRB1*0101/0801 | Autol. PBMC | 5 | |

| BM 9 | DRB1*0801 | 8·2 | ||

| JESTHOM | DRB1*0101 | 2 | ||

| Unrelated | < 2 |

Responses of T-cell lines in the presence of different APC are compared. SI values are therefore shown without standardization to an internal control (as in the case of comparisons between response to RTA and to RTA mutants).

Cells of the homozygous B-EBV cell lines listed were used as APC.

RTA domains and epitopes recognized by human T-cell clones

To identify RTA domains in the region comprising amino acids D124–F267 capable of stimulating T-cell responses, CD4+ T-cell clones were first challenged in vitro with 25–30-mer peptides spanning this RTA sequence (Table 5). T-cell clones derived from donor GF recognized the peptide D124-A150. The GF T-cell line also recognized only peptide D124-A150. The epitope recognized by T-cell clones from donor GF is likely to be contained within the sequence DRLEQLAGNLRENIELG present in peptide D124-A150 but not in peptide N141-I170, representing a stretch of the RTA sequence closer to the C-terminus. Anti-RTA MC T-cell clones responded exclusively to peptide L161-T190 and the MC T-cell line behaved similarly. Inasmuch as T-cell clones of donor MC did not recognize peptides N141-I170 and F181-S210 overlapping the N-terminus and the C-terminus of L161-T190 by 10 aa, respectively (Table 5), it might be inferred that the core region (i.e. fragment C171-R180, sequence CIQMISEAAR) of peptide L161-T190 contained the residues necessary for binding to the restriction elements involved in peptide presentation and in the triggering of the TCR expressed by MC T-cell clones.

Table 5.

Response of MC and GF T-cell clones to RTA-peptides (25–30 mer)

| Donor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | GF | ||||

| Peptide | Sequence* | T-cell line† | T-cell clones‡ | T-cell line† | T-cell clones‡ |

| D124-A150 | DRLEQLA GNLRENIELG NGPLEEAISA | 0 | 0 | 133 | 121·7 ± 9·0 |

| N141-I170 | NGPLEEAISA LYYYSTGGTQ LPTLARSFII | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L161-T190 | LPTLARSFII CIQMISEAAR FQYIEGEMRT | 59 | 92·7 ± 14·0 | 0 | 0 |

| F181-S210 | FQYIEGEMRT RIRNRRSAPN DPSVITLENS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D201-I230 | DPSVITLENS WGRLSTAIQE SNQGAFASPI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S221-I251 | SNQGAFASPI QLQRRNGSKFS VYDVSILIPI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| V242-F267 | VYDVSILIPI IALMVYRCAPP PSSQF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The sequence of the peptides utilized for T-cell stimulations is shown. Single letter code identifies amino acids. Overlapping sequences are evidenced in bold characters.

The values shown represent a percentage of the response to whole RTA (MC T-cell line, SI = 75; GF T-cell line, SI = 4).

The responses of 8 T-cell clones from donor MC and of 3 T-cell clones from donor GF are averaged. The values reported are a percentage of the response to whole RTA (donor MC, SI = 34·2 ± 7·9; donor GF, SI = 8·9 ± 2·1.

We then investigated in greater detail the response of MC T-cell clones aiming, by using short (15-mer or 10-mer) peptides and peptides with N-terminal or C-terminal deletions, to identify the minimal sequence recognized by MC T-cells (summary Table 6). Experiments conducted with 15-mer overlapping peptides revealed that MC T-cell clones responded only to the region C171-E185. Considering the response of MC T-cell clones to peptides with N-terminal or C-terminal deletions it appeared that two minimal epitopes can be identified (i.e. I175-E185 and M174-E185), recognized in the context of the alleles HLA-DRB1*03011 and HLA-DRB1*11011, respectively. It must also be noticed that the allele HLA-DRB1*11011 presents RTA peptides with a lower efficiency than the allele HLA-DRB1*03011. In fact, the response of MC T-cell clones to RTA peptides presented by the APC SWEIG (homozygous for HLA-DRB1*11011) is 36% (in the case of peptide L161-T190), 23% (peptides with N-terminal or C-terminal deletions) and 17% (peptide C171-E185) of that observed when RTA peptides are presented by APC WT49 (homozygous for HLA-DRB1*03011).

Table 6.

Response of MC T-cell clones to RTA peptides and to I175A RTA mutant

| Peptide/protein | Sequence | MC EBV (HLA-DRB1*11011/03011) | APC SWEIG† (HLA-DRB1*11011) | WT49† (HLA-DRB1*03011) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L161-T190 | L | P | T | L | A | R | S | F | I | I | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Q | Y | I | E | G | E | M | R | T | 100* | 100 | 100 |

| L161-I175 | L | P | T | L | A | R | S | F | I | I | C | I | Q | M | I | 2·7 ± 0·4* | |||||||||||||||||

| R166-R180 | R | S | F | I | I | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| C171-E185 | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | 81·4 ± 4·8 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| S176-T190 | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | G | E | M | R | T | 2·0 ± 0·3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| C171-I184 | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | 130·8 ± 5·2‡ | 112 | 104 | |||||||||||||||||

| C171-Y183 | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | 125·2 ± 15·0 | 0 | 90 | ||||||||||||||||||

| C171-Q182 | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | 27·9 ± 12·6 | 0 | 29 | |||||||||||||||||||

| C171-F181 | C | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | 19·8 ± 12·3 | 0 | 30·4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| I172-E185 | I | Q | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | 137·0 ± 8·2 | 143 | 101 | |||||||||||||||||

| Q173-E185 | M | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | 126·2 ± 5·7 | 126 | 101 | |||||||||||||||||||

| M174-E185 | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | 150·2 ± 19·7 | 162 | 104 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| I175-E185 | I | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | 104·8 ± 15·6 | 0 | 87·8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| S176-E185 | S | E | A | A | R | F | Y | I | E | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Autologous PBMC | APCSWEIG | WT49 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RTA I175A | · | · | · | C | I | Q | M | A | S | E | A | A | R | F | Q | Y | I | · | · | · | 15·9 ± 3·6¶ | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

The response of 10 individual T-cell clones of the donor MC is averaged. The response to the 15-mer overlapping peptides (L161-T190, R166-R180, C171-E185 and S176-T190) is a percentage of the response to peptide L161-T190 (SI = 108·6 ± 6·2).

Values shown in these columns represent the response of a pool of five different T-cell clones. The response is a percent of the response to peptide C171-E185 (SI = 6 in the presence of SWEIG; SI = 34·5, in the presence of WT49). Shown are the results of a representative experiment.

The response to N- and C-deletion peptides is a percentage of the response of 5 T-cell clones to the peptide C171-E185 SI = 21·1 ± 2·9).

The response to the mutant RTA I175A is a percentage of the response of 4 T-cell clones to whole RTA (SI = 75·8 ± 8·6). Only the sequence containing the I175 A change is shown (bold).

When 10-mer peptides were used we could observe that the deletion of the I175 residue abolishes the response of MC T-cell clones, irrespective of the presenting allele (Table 6). To characterize the role of I175 further as the possible anchor site for presentation of RTA epitopes in the context of the two HLA-DR alleles we used PCR to substitute I175 with an Ala residue in the whole protein and then evaluated the ability of the I175A point mutant to induce responses in MC T-cell clones. As shown in Table 6, the I175A mutant exhibited an 85% reduction in stimulating potential compared with wild-type RTA when autologous PBMC were used as APC. No T-cell stimulation was observed when homozygous SWEIG or WT49 cells were utilized as APC. However, I175A retained full immunogenicity when used to stimulate T-cell clones from donor GF, who responds to a different RTA domain (data not shown). Moreover, in spite of the fact that I175 is close to residues crucial for RTA catalytic activity [37], in 24-h dose–response cytotoxicity assays against Jurkat cells we found that it retained 55–71% of the enzymatic activity displayed by the wild-type form of RTA.

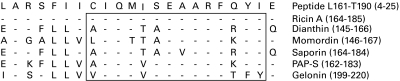

Anti-RTA MC T-cell clones do not recognize RIPs-I showing stretches similar but not identical to fragment L161-T190

Ricin is a member of the ribosome inactivating proteins (RIPs) family which also includes a number of single-chain RIPs-I, such as dianthin, momordin, saporin, pokeweed antiviral protein (PAP) and gelonin [38,39]. The enzymatic subunit of ricin (RTA) and toxins belonging to the RIPs-I group are all of similar size, all carry out the same N-glycosidation reaction and show a high degree of sequence similarity [40]. In Fig. 2 we have aligned the sequences of RTA and several other RIPs-I showing similarity with the RTA peptide L161-T190 recognized by CD4+ T-cell clones from donor MC. These T-cell clones recognize a region of RTA containing the enzymatic site of action of the toxin and which also shows a high degree of similarity with domains belonging to other RIPs-I [38]. To examine whether anti-RTA T-cell clones from donor MC recognized domains of toxins belonging to the RIPs-I family, they were challenged with various heat-denatured RIPs-I in the presence of autologous APC. Failure to respond to RIPs-I containing different residues, compared with RTA, at discrete points in the domain L164 to E185 would help to identify critical amino acids involved in recognition of this stretch of the molecule. We observed no response by MC T-cell clones against the panel of RIPs-I assayed. To make sure that donor MC was not a non-responder against RIPs-I, PBMC from the same donor were challenged with the RIPs-I listed in Fig. 2. With the exception of PAP-S, a good proliferative response was observed against all the RIPs-I assayed (SI ranging between 3·2 and 11). It should be noted that one of the residues differing between RTA and the other RIPs assayed here is I175, thus indirectly confirming the crucial role of this amino acid for recognition by MC T-cell clones.

Fig. 2.

The sequence of peptide L161-T190 (fragment L164-E185 is shown) is aligned to the sequences of RTA and the other RIPs-I listed in the table. Regions considered for the various RIPs-I (numbers in brackets) are as follows: ricin A-chain (aa 164–aa 185), dianthin (aa 145–aa 166), momordin (aa 146–aa 167), saporin (aa 164–aa 184), PAP-S (aa 162–aa 183) and gelonin (aa 199–aa 220). Identities with the sequence of peptide L161-T190 are indicated by dashes, differences are evidenced by indicating the substituded amino acid (one-letter code). Active site regions of the various RIPs are boxed.

DISCUSSION

Several ricin- and ricin A-chain (RTA)-based ITs against various blood-borne as well as solid malignancies have demonstrated potent antitumour effects in vitro and in animal models [1]. Some of these have already undergone clinical phase-I/II trials. Applied to broad groups of patients with various malignancies, targeted toxins yielded response rates of 25–35% with response durations averaging months [41]. In particular, ITs made with RTA or with blocked ricin have been used successfully in the treatment of post-transplant lymphoma [42], T-cell LGL leukaemia [43] and a variety of other haematological malignancies [44]. Nevertheless, the appearance of anti-ITs antibodies limits the efficacy of antitumour ITs severely and hampers the development of optimized administration schedules based on repeated courses of therapy, thus often restricting the treatment to single bolus infusions [1,41]. Therefore, strategies are warranted that may ultimately allow injection of RTA-ITs in non-immunocompromised humans without eliciting the production of unwanted blocking antibodies. To this end, mapping RTA T-cell epitopes is an essential prerequisite. We thus set out to investigate anti-RTA responses in vitro with the aim of identifying T-cell dependent epitopes.

The majority of anti-RTA T-cell clones developed showed a T-helper CD4+ phenotype. These T-cell clones were studied in further detail. CD8+ T-cell clones were also obtained (donor GF and OP), although with a lower frequency. The possible role of such CD8+ T-cells in anti-RTA responses in vivo will have to be determined.

Evaluation of cytokine mRNA expression indicated that the CD4+ T-helper cell clones assayed belonged to either a TH0 or TH1 T-cell population. The lack of polarization/prevailing TH1 polarization may have been favoured by the culture conditions adopted in our studies without necessarily representing the predictable outcome of in vivo RTA inoculation.

In our experiments primary in vitro immunization was chosen because it may offer a wide representation of the potential anti-RTA TCR repertoire available in non-immunized individuals. In two of the subjects examined, TCR recognition of RTA epitopes appeared to involve a limited set of Vβ chains (Vβ8 for donor MC and Vβ2 for donor GF). Restricted Vβ usage is unlikely to represent a sampling error due to cloning procedures because non-clonal anti-RTA T-cell lines also express a limited set of Vβ chains (donor MC) or a quantitatively greater expression of some Vβ chains (donor GCA). Restricted usage of Vβ chains appears to take place early after Ag stimulation. In fact, T-cell cloning procedures took place after only two cycles of stimulation with Ag and T-cell lines displayed restricted Vβ chain expression after only 2–4 cycles of stimulation with RTA. Restricted TCR Vβ usage could be exploited to control unwanted responses by RTA-specific T-cell clones, as shown for autoimmune T-cell mediated reactions [45,46]. Control T-cell clones directed against a non-relevant Ag (T-cell clones GF 6TT and GF 7TT to tetanus toxoid) expressed a Vβ chain different from the one expressed by anti RTA T-cell clones obtained from the same individual, again confirming that Vβ chain selection is likely to be an RTA-driven process.

Using in-frame deletion mutants of RTA we found that all T-cell clones derived from three out of four HLA-unrelated donors recognize the central part of the molecule, comprised of residues D124 and Q223. Taken together our data indicate that the region D124-F267 may represent the principal source of immunodominant epitopes in the RTA molecule. This finding, however, will have to be confirmed in a larger number of human subjects. It must be also mentioned that the RTA domains recognized in secondary responses of ITs treated patients might differ from those found in our study; however, the information gathered from both in vitro and in vivo studies could be combined to devise strategies to prevent/reduce the anti-RTA immune response.

Experiments aimed at defining the HLA elements restricting the response to RTA epitopes by T-cell clones indicated that HLA-DR molecules are the dominant restricting elements of this response. A panel of homozygous B-EBV cell lines expressing the HLA-DR alleles possibly involved in the restriction phenomenon enabled the identification of the HLA-DR alleles presenting the RTA epitopes recognized by MC and GF T-cell clones. We could thus conclude that MC T-cell clones recognize RTA epitopes in the context of the HLA-DRB1*11011 and HLA-DRB1*03011 alleles, whereas GF T-cell clones recognize RTA epitopes in the context of HLA-DRB1*0801. MHC class II allele DRB1 *11011 is found with a frequency (genomic) of 8·3–20·6% in the Italian Caucasian population and is one of the HLA-DRB1 alleles occurring with a higher frequency in most other Caucasian populations. The HLA-DRB1*03011 allele is distributed in the Italian Caucasian population with a frequency of 7·0–9·5% [47] whereas the HLA-DRB1*0801 allele is found with a lower frequency (1·2–3·6% in the Italian Caucasian population) [47]. Whether these epitopes could behave as promiscuous epitopes will have to be determined experimentally. Recognition of RTA domains in association with multiple MHC class II alleles would obviously broaden the potential usefulness of immunoprevention/immunosuppression strategies aimed at discrete RTA epitopes.

The use of specific peptides enabled the characterization of RTA domains recognized by T-cell clones from two donors (GF and MC). 25–30-mer peptides allowed us to identify a 17 aa RTA stretch (DRLEQLAGNLRENIELG) containing epitope(s) recognized by GF T-cell clones in the context of HLA-DRB1*0801. Further investigation will be needed to identify the minimal epitope recognized by GF T-cell clones. Using 15-mer overlapping peptides and N-terminal and C-terminal deletions, more detailed information could be gathered on the RTA domains recognized by MC T-cell clones. It thus appeared that the shortest peptide recognized in the context of HLA-DRB1*03011 is I175-E185, whereas the shortest peptide that provided a stimulating signal when presented by the allele HLA-DRB1*11011 is M174-E185. However, it should be noted that experiments with N-terminal and C-terminal deleted peptides revealed that residues E185 and I184 are dispensable for presentation by the allele HLA-DRB1*03011, thus restricting the minimal epitope to the sequence I175-Y183. On the other hand, E185 appears not to be necessary for presentation by the allele HLA-DRB1*11011, but M174 and I184 seem to be required. This suggests that the minimal epitope recognized in the context of HLA-DRB1*11011 could be M174-I184.

Cell lines homozygous for HLA-DRB1*11011 (SWEIG) or HLA-DRB1*03011 (WT49) present stimulating peptides with different efficiency. This could be due to the different binding properties of the peptides to the two presenting alleles. In fact, HLA-DRB1*11011 requires the presence of residue M174 for T-cell activation, whereas HLA-DRB1*03011 does not. Alternatively, differences in the stimulating abilities of the two alleles could be explained in terms of TCR recognition. Binding experiments with the appropriate peptides will help to address this question.

Several observations indicated that I175 could be the primary anchor site for the minimal epitope(s) recognized in the context of the two HLA-DRB1 alleles: (1) a 10-mer S176-E185 peptide lacking I175 failed to stimulate MC T-cell clones in the context of either allele; (2) a I175A RTA mutant showed drastically reduced ability to stimulate MC T-cell clones; and (3) RIPs differing from RTA at positions corresponding to I175 are not recognized by MC T-cell clones. The crucial role of I175 is compatible with it being the primary anchor site for both minimal sequences identified (i.e. I175-Y183 and M174-I184). A178, R180, F181 and Y183 would then represent the four other anchor residues binding to the MHC class II molecule pockets. The chemistry of the five anchor sites required for binding to the MHC class II molecules would fit the main criteria defining the ‘pocket specificity’ of a peptide recognized in the context of the allele HLA-DRB1*03011 [48]. This is also in accordance with the findings of Hammer et al. [49], demonstrating that deletion of the primary anchor residue (as in our 10-mer peptides) or substitution with Ala (as in our I175A RTA mutant) prevents binding to HLA-DR molecules. The fact that residue 175, a Ile, could behave as the primary anchor site is also supported by Wu et al. [50], who found that substituting a primary anchor Leu with Ile would not interfere with MHC binding or T-cell stimulation, whereas substitution with Ala abolished both.

Thus, having identified the minimal sequences needed to stimulate T-cells and the possible primary anchor residue, strategies might now be undertaken to minimize anti-RTA responses in vivo: (1) the RTA mutant I175A does not stimulate MC T-cell clones and is not recognized in the context of the two alleles studied by us. ITs constructed using this mutant might therefore escape immune recognition in vivo. We found that I175A retains 55–71% activity with respect to the wild-type toxin in a 24-h assay in vitro. We have no information concerning its long-term in vitro or in vivo stability, however. If I175A behaves like the wild-type counterpart, one could produce ITs with antitarget cell cytotoxicity and reduced immunogenicity in vivo in the context of the alleles described in this paper. (2) Antagonist or partial agonist altered peptide ligands (APLs) could be designed based on the epitopes described herein. APLs, analogues of the wild-type peptide, are partial agonists of the TCR and can generate abortive activation phenomena in T-cells, leading to hyporesponsiveness and to the induction of anergy in an Ag-specific context [51]. Their success in the treatment of experimental models of autoimmune diseases [52] may also encourage their use as inhibitors of anti-RTA immune responses.

In conclusion, we believe that the scene is set for studies aimed at developing strategies for anti-RTA immune response manipulation in humans by either deletion/substitution of key residues involved in recognition of the RTA epitopes identified by T-cell clones or by inducing specific unresponsiveness through the use of altered peptide ligands.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by AIRC, MURST and Regione Veneto. Chiron is gratefully aknowledged for supplying human recombinant IL-2. Dr C. Servis (Institut de Biochimie, Université de Lausanne) kindly synthesized the peptides used in our study. Prof. F. Stirpe and Prof. L. Barbieri (Department of Experimental Pathology, University of Bologna) are gratefully thanked for providing RIPs-I. We are also indebted to Dr R. S. Accolla (Department of Clinical and Biological Sciences, University of Insubria, Varese) for supplying anti-MHC class-II monoclonal antibodies and to Dr C. Lunardi (Medicina Interna B, University of Verona) for valuable advice. We also thank Dr L. Adorini (Roche Milano Ricerche) for critically reviewing the manuscript. Dr M. Fabbi (Advanced Biotechnology Center, Genova) and Dr D. Ramarli (Azienda Ospedaliera di Verona) are thanked for suggestions and advice and for careful review of our manuscript. The expert technical help of Ms. Sabrina Righetti is also thankfully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trush GR, Lark LR, Clinchy BC, Vitetta E. Immunotoxins: an update. Ann Rev Immunol. 1996;14:49–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godal A, Fodstad Ø, Pihl A. Antibody formation against the cytotoxic proteins abrin and ricin in humans and mice. Int J Cancer. 1983;32:515–21. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910320420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harkonen S, Stoudemire JB, Mischak LE, et al. Toxicity and immunogenicity of monoclonal antimelanoma antibody-ricin A-chain immunotoxins in rats. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramakrishnan S, Houston LL. Prevention of growth of leukemia cells in mice by monoclonal antibodies directed against Thy 1.1 antigen disulfide linked to two ribosomal inhibitors: pokeweed antiviral protein or ricin A-chain. Cancer Res. 1982;44:1398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertler AA, Schlossman DM, Borowitz MJ, Poplack DG, Frantiel AE. An immunotoxin for the treatemnt of T‐acute lymphoblastic leukemic meningitis: studies in resus monkeys. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1989;28:59–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00205802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner LM, O'Dwyer J, Kitson J, et al. Phase I evaluation of an anti-breast carcinoma monoclonal antibody 260F9-recombinant ricin A-chain immunoconjugate. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4062–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byers VS, Rodvien R, Grant K, et al. Phase I study of monoclonal antibody-ricin A-chain immunotoxin XomaZyme-791 in patients with metastatic colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6153–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeMaistre CF, Rosen S, Frankel A, et al. Phase I trial of H65-RTA immunoconjugate in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1991;78:1173–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amlot PL, Stone MJ, Cunningham D, et al. A phase I study of an anti-CD22-deglycosylated ricin A-chain immunotoxin in the treatment of B-cell lymphomas resistant to conventional therapy. Blood. 1993;82:2624–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sausville EA, Headlee D, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Continuous infusion of the anti-CD22 immunotoxin IgG-RFB4-SMPT-dgA in patients with B-cell lymphoma: a phase I study. Blood. 1995;85:3457–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LoRusso PM, Lomen PL, Redman PG, et al. Phase I study of monoclonal antibody-ricin A-chain immunoconjugate Xomazyme-791 in patients with metastatic colon cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1995;18:307–12. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199508000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engert A, Diehl V, Schnell R, et al. A phase-I study of an anti-CD25 ricin A-chain immunotoxin (RFT5-SMPT-dgA) in patients with refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;89:403–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mischak RP, Foxall C, Rosendorf LL, et al. Human antibody responses to components of the monoclonal antimelanoma antibody ricin A-chain immunotoxin XomaZyme-MEL. Mol Biother. 1990;2:104–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hird V, Verhoeyen M, Bradley RA, et al. Tumor localisation with a radiolabelled reshaped human monoclonal antibody. Br J Cancer. 1991;64:911–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laske DW, Youle RJ, Oldfield EH. Tumor regression with regional distribution of the targeted toxin TF-CRM107 in patients with malignant brain tumors. Nat Med. 1997;3:1362–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sweeney EB, Murphy JR. Diphtheria toxin-based receptor-specific chimaeric toxins as targeted therapies. Essays Biochem. 1995;30:119–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoudemire JB, Mischak R, Foxall C, et al. The effects of cyclophosphamide on the toxicity and immunogenicity of ricin A-chain immunotoxins in rats. Mol Biother. 1990;2:179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byers VS, Austin EB, Clegg JA, et al. Suppression of antibody responses to ricin A-chain (RTA) by monoclonal anti-RTA antibodies. J Clin Immunol. 1993;13:406–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00920016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin FS, Youle RJ, Johnson VG, et al. Suppression of the immune response to immunotoxins with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1991;146:1806–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oratz R, Speyer JL, Wernz JC, et al. Antimelanoma monoclonal antibody-ricin A-chain immunoconjugate (XMMME-001-RTA) plus cyclophosphamide in the treatment of metastatic malignant melanoma: results of a phase II trial. J Biol Response Mod. 1990;9:345–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrifield RB. Solid-phase peptide synthesis. Adv Enzymol. 1969;32:221–96. doi: 10.1002/9780470122778.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeMagistris MT, Romano M, Bartoloni A, et al. Human T cell clones define S1 subunit as the most immunogenic moiety of pertussis toxin and determine its epitope map. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1519–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C, Levine A, Branton D. Copper staining: a five-minute protein stain for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:308–12. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Hare M, Roberts LM, Thorpe PE, et al. Expression of ricin A-chain in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1987;216:73–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80759-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taswell C. Limiting dilution assays for the determination of immunocompetent cell frequencies. I. Data analysis. J Immunol. 1981;126:1614–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mingari MC, Gerosa F, Carra G, et al. Human interleukin-2 promotes proliferation of activated B cells via surface receptors similar to those of activated T cells. Nature. 1984;312:641–3. doi: 10.1038/312641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chignola R, Colombatti M, Dell'Arciprete L, et al. Distribution of endocytosed molecules to intracellular acidic environments correlates with immunotoxin activity. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:1117–23. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scupoli MT, Sartoris S, Tosi G, et al. Expression of MHC class I and class II antigens in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Tissue Antigens. 1996;48:301–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Deans RJ, et al. Defining protective responses to pathogens: cytokine profiles in leprosy lesions. Science. 1991;254:277–9. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunardi C, Marguerie C, So AK. An altered repertoire of T-cell receptor V gene expression by rheumatoid synovial fluid T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:440–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi Y, Kotzin B, Merron L, et al. Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus toxin ‘superantigens’ with human T cells. Immunology. 1989;86:8941–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pera C, Delfino L, Morabito A, et al. HLA-A typing: comparison between serology, the amplification refractory mutation system with polymerase chain reaction and sequencing. Tissue Antigens. 1997;50:372–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delfino L, Morabito A, Longo A, et al. HLA-C high resolution typing: analysis of exons 2 and 3 by sequence based typing and detection of polymorphisms in exons 1–5 by sequence specific primers. Tissue Antigens. 1998;52:251–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson J, Malik A, Parham P, et al. IMGT/HLA database – a sequence database for the human major histocompatibility complex. Tissue Antigens. 2000;55:280–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.550314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katzin BJ, Collins EJ, Robertus JD. Structure of ricin A-chain at 2·5 Å. Proteins. 1991;10:251–9. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartley MR, Legname G, Osborn R, et al. Single-chain ribosome inactivating proteins from plants depurinate Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. FEBS Lett. 1991;290:65–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stirpe F, Barbieri L. Ribosome-inactivating proteins up to date. FEBS Lett. 1986;195:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Endo Y, Mitsui K, Motizuki M, et al. The mechanism of action of ricin and related toxic lectins on eukaryotic ribosomes. The site and the characteristics of the modification in 28 S ribosomal RNA caused by the toxins. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5908–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frankel AE, Tagge EP, Willingham MC. Clinical trials of targeted toxins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:307–17. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senderowicz AM, Vitetta E, Headlee D, et al. Complete sustained response of a refractory, post-transplantation, large B-cell lymphoma to an anti-CD22 immunotoxin. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:882–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-11-199706010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frankel AE, Laver JH, Willingham MC, et al. Therapy of patients with T-cell lymphomas and leukemias using an anti-CD7 monoclonal antibody-ricin A-chain immunotoxin. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26:287–98. doi: 10.3109/10428199709051778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Toole JE, Esseltine D, Lynch TJ, et al. Clinical trials with blocked ricin immunotoxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;234:35–56. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72153-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Acha-Orbea H, Mitchell DJ, Timmermann L, et al. Limited heterogeneity of T cell receptors from lymphocytes mediating autoimmune encephalomyelitis allows specific immune intervention. Cell. 1998;54:263–73. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90558-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urban JL, Kumar V, Kono DH, et al. Restricted use of T cell receptor V genes in murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis raises possibilities for antibody therapy. Cell. 1998;54:577–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gjertsen DW, Terasaki PI. HLA. Lenexa, Kansas: ASHI; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rammensee HG. Chemistry of peptides associated with MHC class I and class II molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammer J, Belunis C, Bolin D, et al. High affinity binding of short peptides to major histocompatibility complex class II molecules by anchor combinations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4456–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu S, Gorski J, Eckels DD, et al. T cell recognition of MHC class II-associated peptides is independent of peptide affinity for MHC and sodium dodecyl sulfate stability of the peptide/MHC complex. Effects of conservative amino acid substitutions at anchor position 1 of influenza matrix protein19–31. J Immunol. 1996;156:3815–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM. Altered peptide ligand-induced partial T cell activation: molecular mechanisms and role in T cell biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderton S, Burkhart C, Metzler B, et al. Mechanisms of central and peripheral T-cell tolerance: lessons from experimental models of multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev. 1999;169:123–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]