Abstract

Secretions of Paneth, intermediate and goblet cells have been implicated in innate intestinal host defense. We have investigated the role of T cells in effecting alterations in small intestinal epithelial cell populations induced by infection with the nematode Trichinella spiralis. Small intestinal tissue sections from euthymic and athymic (nude) mice, and mice with combined deficiency in T-cell receptor β and δ genes [TCR(β/δ)−/–] infected orally with T. spiralis larvae, were examined by electron microscopy and after histochemical and lineage-specific immunohistochemical staining. Compared with uninfected controls, Paneth and intermediate cell numbers increased significantly in infected euthymic and nude mice but not infected TCR(β/δ)−/– mice. Transfer of mesenteric lymph node cells before infection led to an increase in Paneth and intermediate cells in TCR(β/δ)−/– mice. In infected euthymic mice, Paneth cells and intermediate cells expressed cryptdins (α-defensins) but not intestinal trefoil factor (ITF), and goblet cells expressed ITF but not cryptdins. In conclusion, a unique, likely thymic-independent population of mucosal T cells modulates innate small intestinal host defense in mice by increasing the number of Paneth and intermediate cells in response to T. spiralis infection.

Keywords: innate immunity, defensin, goblet cells

Introduction

The small intestinal epithelium is a dynamic monolayer of four main cell types: absorptive enterocytes, goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells and Paneth cells. All cells of the monolayer are derived from multipotent stem cells present near the base of each crypt [1,2]. Enterocytes, goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells differentiate as they migrate from the crypt to the villus tip, where they are lost by apoptosis and/or exfoliation. The period from emergence from stem cells to the loss of mature epithelial cells at the villus tips takes 2–5 days in mice and other species [3]. A fourth epithelial lineage, Paneth cells, also derives from stem cells but migrates down to the crypt base [4], where they survive longer than the other three lineages, residing at the crypt base for approximately 20 days [3,5]. Normally, Paneth cells are not seen above the stem cells or on villi. Also, they are absent from the normal colon but may appear in chronic inflammatory diseases of the colon such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease [6,7], implying the induction of stem cells to differentiate along this lineage in response to factors produced in the inflamed mucosa. Currently, the factors that regulate the commitment of multipotent stem cells to differentiate along one lineage versus another are unknown [8]. The capacity of stem cells to differentiate preferentially along a particular lineage may allow the host to respond to an infectious or noxious challenge via enhanced secretion of protective factors and mediators produced by that particular cell type.

Secretory products of two small intestinal epithelial cell types, goblet cells and Paneth cells, appear to have a role in innate host defense in the intestine. Goblet cell-derived mucin glycoproteins are important in the formation of a surface layer of mucus, which inhibits the interaction between luminal micro-organisms and surface epithelial cells [9]. Recent studies have shown that goblet cells also produce intestinal trefoil factor (ITF; 10), which enhances defense in the viscoelastic mucus layer [11] and facilitates the process of epithelial restitution to re-establish epithelial continuity and barrier function following injury [12,13].

The Paneth cells have also been implicated in mucosal defence. These cells synthesize several molecules with potent biological activities, including tumour necrosis factor-α [14,15], epidermal growth factor [16], guanylin [17], matrilysin [18], phospholipase A2 [19], lysozyme [20] and α-defensins, termed cryptdins [21,22]. In normal small bowel, cryptdins are found in Paneth cells, and mice deficient in activated cryptdins are impaired in clearance of Gram-negative enteric infections [23].

Infection of mice with Trichinella spiralis, a parasitic nematode, leads to a T cell-dependent enteropathy characterized by villus atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and goblet cell hyperplasia [24–26]. Here, we report that the numbers of Paneth and intermediate cells increase and are more widespread in the epithelial monolayers of T. spiralis-infected mice. Although intermediate cells have morphological features of both Paneth cells and goblet cells, they expressed cryptdins but not ITF. Cyclosporin treatment significantly reduced Paneth and intermediate cell numbers in T. spiralis-infected mice. An increase in Paneth and intermediate cells was seen in T. spiralis-infected athymic mice, but in mice deficient in the T-cell antigen receptor [TCR(β/δ)−/–], such an increase only occurred following transfer of mesenteric lymph node cells from wild-type mice. These studies suggest that a unique population of mucosal T cells may regulate innate intestinal host defense.

Materials and methods

Animals

Eight-week-old, age-matched, specific pathogen-free, female NIH and BALB/c inbred mice (Harlan-Olac Ltd, Bicester, UK) and CD1 outbred mice (Charles River Ltd. Margate, Kent, UK) were maintained in a conventional animal house. Each experimental group consisted of five animals. Athymic CD1 nu/nu mice were obtained from Charles River. The TCR(β/δ)−/– (C57.BL/6 background) [27] and nude mice were kept in microisolator cages and fed autoclaved food and water. All manipulations were carried out under laminar flow.

In some studies, NIH mice were administered 50 mg/kg cyclosporin subcutaneously (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Surrey, UK) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), daily for 10 days. The control group of mice was administered PBS only.

Parasitological technique

Trichinella spiralis was maintained and recovered as described previously [28] and mice were infected via oral administration of 300–400 infective larvae (L1). On various days after infection, the mice were sacrificed and intestinal samples taken from the duodenum (10 cm distal to the pylorus), jejunum (20 cm distal to pylorus), ileum (30 cm distal to pylorus) and colon (distal to caecum). Worm counts were performed on the remaining intestine following incubation of the opened small intestine in warm (37°C) Hanks Balanced Salt solution (Gibco) for 1 h.

Cell transfer experiments

Mesenteric lymph nodes were obtained from wild-type C57.BL/6 mice 8 days after infection with 300 T. spiralis larvae. Single cell suspensions were obtained and washed four times in 10% FCS/RPMI before transfer. Recipient TCR(β/δ)−/– mice (C57.BL/6 background) were each injected intraperitoneally with 3 × 107 mesenteric lymph node cells (MLNCs) 10 days before challenge with T. spiralis. Small intestinal tissue samples were taken 12 days after infection and studied as described below.

Histological techniques

Intestinal tissue samples were fixed in Carnoy's fluid or in 10% buffered formalin. All samples were subsequently dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were stained with Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) to visualize goblet cells, 1% acidic (pH 0·3) Alcian blue for mast cells, or phloxine-tartrazine for Paneth and intermediate cells [29,30]. Numbers of cells of interest are expressed per 10 villus crypt units (VCU).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on tissue sections using antibodies to cryptdin prosegment [23] and ITF [10] using Vectastain ABC peroxidase kit (Vector Labs, Burlington, CA, USA). In brief, sections (5 µm thick) were heated at 60°C for 1 h, rehydrated, and microwaved in Antigen Unmasking Solution (Vector Labs). After washing in PBS, the sections were immersed in 0·3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After blocking non-specific binding, the sections were incubated with antibodies to prosegment of cryptdin [23], ITF [10], pre-immune sera (control) or PBS. Following incubation with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies, streptavidin-peroxidase complex solution was applied before incubation with peroxidase substrate.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Tissue samples were fixed in 2·5% (v/v) gluteraldehyde in 0·1 m cacodylate buffer and processed for TEM.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean (± s.e.m.) and were analysed by one-way analysis of variance and Student's t-test.

Results

Phloxine-tartrazine staining shows increase in Paneth cells in the small intestine of T. spiralis-infected mice

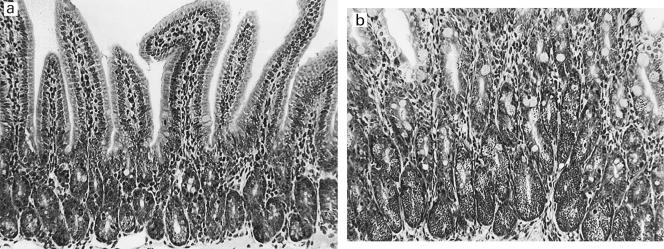

Paneth cells were identified by the staining of their characteristic apical secretory granules with phloxine-tartrazine [29,30]. In control NIH and BALB/c mice, phloxine-tartrazine positive cells were seen only at the base of crypts (Fig. 1a). On days 8–14 after infection with T. spiralis, phloxine-tartrazine positive cells occupied most of the crypt (basal and upper portions), and some positive cells were also seen along the villi and at villous tips (Fig. 1b). No phloxine-tartrazine positive cells were seen in control or infected colon (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in normal (a) and Trichinella spiralis-infected (b) duodenal mucosa. Mucosal samples were collected from control (uninfected) and T. spiralis-infected (for 14 days) BALB/c mice, and sections were stained histochemically with phloxine-tartrazine. In normal mice, positively-stained Paneth cells are confined to the crypt base. Following infection with T. spiralis, there is a marked increase in positive cells in the crypts. Some positive cells are also seen along the villi.

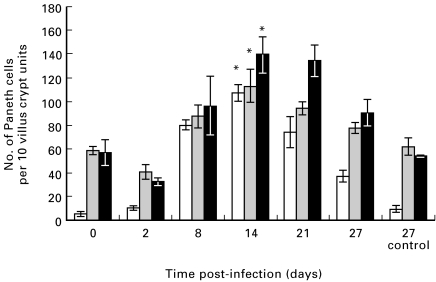

Phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in sections of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum were counted in uninfected control mice and in mice infected with T. spiralis. Infected BALB/c mice showed a marked increase in the number of phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in all regions of the small intestine (Fig. 2). A similar increase in these cells also occurred in the small intestine of NIH mice following infection with T. spiralis. [mean (± s.e.m.) of phloxine-tartrazine positive cells per 10 villus crypt units in control (days 0 and 27 combined) versus infected (day 8 or 14) NIH mice: duodenum – 7·0 (± 2·3) versus 55·5 (± 4·7), P < 0·001; jejunum – 31·7 (± 3.1) versus 77·4 (± 1.4) P < 0·05; ileum – 20·6 (±3·3) versus 57·7 (± 6.8), P < 0·001]. In both strains of mice, the number of phloxine-tartrazine positive cells peaked at days 8–14 after infection in the duodenum and jejunum, but between days 14–21 in the ileum. Over the subsequent days, the number of phloxine-tartrazine positive cells decreased such that at 27 days post-infection, the cell numbers were similar to those seen in control mice. Worms were completely expelled by day 14 in NIH mice and by day 21 in BALB/c mice (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Numbers of phloxine-tartrazine positive cells (per 10 crypt villus units) in BALB/c mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Data are shown as mean (± s.e.m.). There is a marked increase in phloxine-tartrazine positive cells throughout the small intestine: (□), duodenum; ( ), jejunum; (▪), ileum *P < 0·001 versus uninfected controls.

), jejunum; (▪), ileum *P < 0·001 versus uninfected controls.

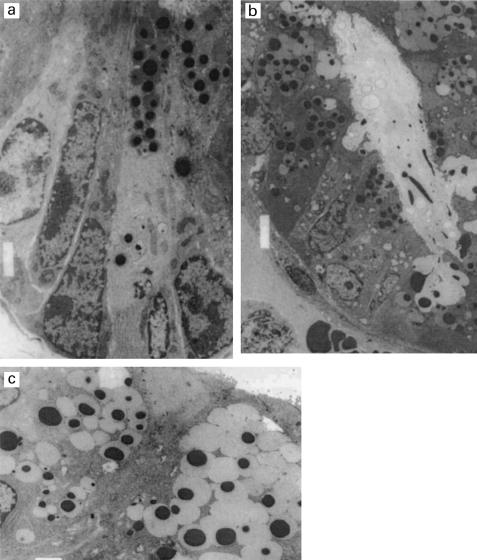

Many of the phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in infected mice are intermediate cells

TEM studies confirmed that in contrast to control uninfected mice (Fig. 3a), crypts of infected mice contained large numbers of Paneth cells. Cells with ultrastructural features characteristic of intermediate cells, i.e. containing mucin-rich secretory granules with electron-dense cores, were also abundant in infected mice. Many of the Paneth and intermediate cells appeared to be releasing granules into the lumen (Fig. 3b). The phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in the upper portion of crypts and on villi had ultrastructural features associated with intermediate cells (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3a.

Transmission electron micrographs of duodenal crypts of Lieberkuhn of control (a) and Trichinella spiralis-infected (b) BALB/c mice. In (a), two Paneth cells containing electron-dense granules are present at the crypt base. By contrast, Paneth cells occupy most of the crypt in (b), and some cells are seen to be discharging granules into the lumen. In (c), two intermediate cells (containing granules with electron-dense cores and pale halos) are present on the side of a villus of a duodenal section of a T. spiralis-infected BALB/c mouse.

Intermediate cells express cryptdins but not ITF

In normal, uninfected mice, granules in Paneth cells at the base of crypts were immunoreactive for cryptdin prosegment, a general feature of all cryptdin precursors. Staining of sequential intestinal sections showed that all phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in infected mice were exclusively immunoreactive for cryptdins. Thus, the intermediate cells present predominantly at the upper portion of crypts and on villi expressed Paneth cell-specific defensins.

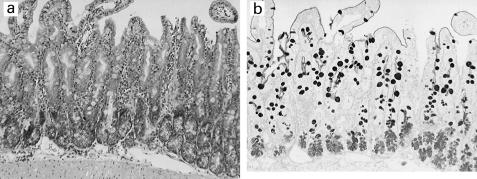

Alcian blue PAS stains mucin, and both goblet cells and Paneth cells of control uninfected mice stained positively, with Paneth cells staining less strongly than goblet cells. Following infection with T. spiralis, the size and number [duodenal sections of BALB/c mice, uninfected controls – mean 127·0 (± s.e.m. 8·2) versus day 14 infected sections 256·9 (± 15·4), P < 0·01] of goblet cells increased. The phloxine-tartrazine positive intermediate cells were also strongly positive for Alcian blue PAS (Fig. 4a,b).

Fig. 4.

Phloxine-tartrazine positive cells in Trichinella spiralis-infected mouse are also Alcian blue PAS positive. Sequential sections of intestinal tissue taken 14 days post-infection with T. spiralis were stained histochemically with phloxine-tartrazine (a) and Alcian blue PAS (b).

Intestinal trefoil factor (ITF) is normally expressed only by goblet cells in the small and large intestine [10]. Since the intermediate cells in infected mice were immunoreactive for cryptdin and stained strongly with Alcian blue PAS, studies were performed to determine if they also express ITF. Studies in serial sections of intestinal samples from infected mice (Fig. 5a-c) showed strong ITF immunoreactivity in goblet cells, but none of the phloxine-tartrazine positive intermediate cells were immunoreactive. Thus, intermediate cells do not express ITF, a goblet cell-specific protein.

Fig. 5.

Paneth and intermediate cells in Trichinella spiralis-infected mice do not express intestinal trefoil factor (ITF). Sections of intestinal tissue were taken 14 days post-infection with T. spiralis and stained immunohistochemically using anti-ITF antibody (a, b) and histochemically with phloxine-tartrazine (c). Figure 5a shows that cells in the base and upper portions of crypts (Paneth and intermediate cells) do not express ITF. Figures 5b and 5c represent sequential sections and show that phloxine-tartrazine positive intermediate cells (arrowed) on the lateral aspects of villi do not express ITF.

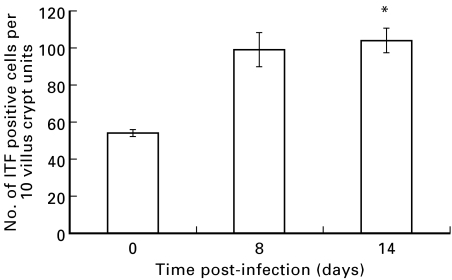

Counts of ITF positive goblet cells in the duodenum of BALB/c mice showed a significant increase following infection with T. spiralis (Fig. 6). Since intermediate cells do not express ITF (see above), these studies confirm an increase also in goblet cell numbers in the parasite-infected mice.

Fig. 6.

Increase in ITF positive cells in the duodenum of Trichinella spiralis-infected mice. Duodenal sections of uninfected control and T. spiralis-infected (days 8 and 14 post-infection) BALB/c mice were stained immunohistochemically with anti-ITF antibody, and the number of immunopositive cells are expressed per 10 crypt villus units. Data are shown as mean (± s.e.m.). *P < 0·01 versus uninfected controls.

Cyclosporin treatment reduces the number of Paneth and intermediate cells in T. spiralis-infected mice

Goblet cell hyperplasia in T. spiralis-infected rodents is regulated by T cells [25,26]. To investigate the role of T lymphocytes in the increase in Paneth and intermediate cell numbers in the intestine of T. spiralis-infected mice, the effect of cyclosporin was studied. There was a significant reduction in the number Paneth and intermediate cells in the small intestine of T. spiralis-infected mice treated with cyclosporin (T. spiralis infection only – 101·7 (± 9·4) positive cells per 10 villus crypt units, T. spiralis infection + cyclosporin – 69·6 (±9·3), P < 0·025). However, the number of Paneth and intermediate cells in infected mice treated with cyclosporin remained significantly higher than in non-infected controls[69.6 (± 9.3) versus 15·2 (±2·2), P < 0·025]. The in vivo efficacy of cyclosporin in treated mice was confirmed by a marked reduction in the number of mast cells present in intestinal sections of infected mice [84·0 (±4.6) versus 9·9 (±2·3), P < 0·001].

Paneth and intermediate cell numbers increase in T. spiralis-infected athymic mice but not TCR(β/δ)−/– mice

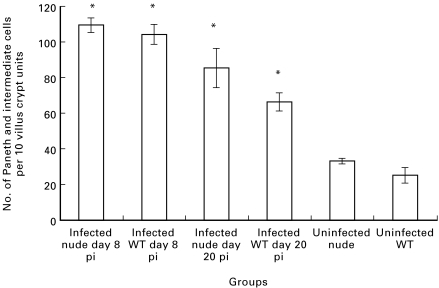

To investigate further the importance of T cells in the increase in intestinal Paneth and intermediate cells following T. spiralis infection, athymic and TCR(β/δ)−/– mice were studied. As for studies in NIH and BALB/c mice (see above), infection with T. spiralis induced an increase in Paneth and intermediate cells in the intestine of wild-type CD1 mice, and a similar increase in Paneth and intermediate cells was seen in the small intestine of athymic mice with a CD1 background (Fig. 7). Moreover, intermediate cells were also seen on the lateral aspect of villi in the wild-type and athymic animals. As expected, and in contrast to wild type mice, worm expulsion was delayed in the athymic mice (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Numbers of Paneth and intermediate cells in CD1 athymic (nude) and wild-type (WT) mice increase following infection with Trichinella spiralis. Duodenal sections of uninfected control and T. spiralis-infected (8 and 20 days post-infection, pi) mice were stained with phloxine-tartrazine and positive cells were counted as described above. Data are shown as mean (± s.e.m.). *P <0·01 versus uninfected controls.

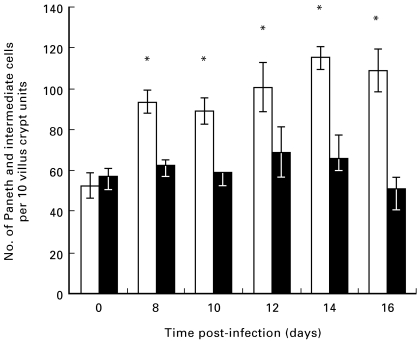

In wild-type C57.BL/6 mice, T. spiralis infection induced an increase in Paneth and intermediate cells, but this was not the case in TCR(β/δ)−/– mice (Fig. 8). Worm expulsion was delayed in TCR(β/δ)−/– mice (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Numbers of Paneth and intermediate cells increase in the duodenum of Trichinella spiralis-infected wild-type C57.BL/6 mice (□) but not TCR(β/δ)−/– mice (▪). Duodenal sections of uninfected control and T. spiralis-infected mice (days 8–16 post-infection) were stained with phloxine-tartrazine and positive cells were counted as described above. Data are shown as mean (± s.e.m.). *P < 0·01 versus uninfected mice.

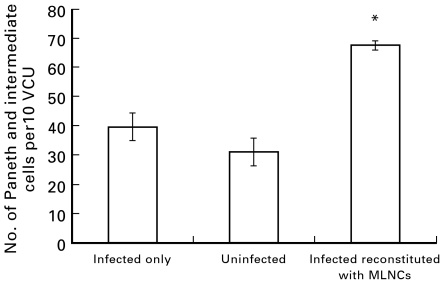

Transfer of mesenteric lymph node cells (MLNCs) induces an increase in Paneth and intermediate cells in T. spiralis-infected TCR(β/δ)−/– mice

To obtain further evidence for a role of T cells in the increase in Paneth and intermediate cells, adoptive transfer experiments were performed using MLNCs, obtained from T. spiralis-infected wild-type C57.BL/6 mice. Compared with infection only controls, transfer of MLNCs prior to T. spiralis infection led to a significant increase in the number of Paneth and intermediate cells in TCR(β/δ)−/– mice (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Transfer of MLNCs induces an increase in Paneth and intermediate cells in Trichinella spiralis-infected TCR(β/δ)−/– mice. MLNCs were obtained from T. spiralis-infected wild-type C57.BL/6 mice and intraperitoneally injected into TCR(β/δ)−/– mice 10 days prior to challenge with T. spiralis. Numbers of Paneth and intermediate cells in duodenal sections were determined 12 days after infection. *P = 0·005 versus infected and uninfected controls.

Discussion

In rodents, infection with the parasites T. spiralis and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis induces a well characterized sequence of changes in the small intestine, which include villous atrophy, increase in crypt length and an increase in goblet cell numbers [24–26]. During the course of infection, the animals become immunized, leading to rapid expulsion of the parasites upon subsequent challenge. Lymphocyte transfer studies have shown that this immunity is mediated by T cells [31]. Studies of cytokine expression defined an initial Th1 response followed by a Th2 response [32]. In addition to mediating host protection against the parasite, the Th2 type response also appears to be important in the induction of goblet cell accumulation [26]. In this study, we have used the mouse T. spiralis infection model to investigate changes in Paneth cells in the small intestine.

Studies in four different strains of mice (NIH, BALB/c, CD1 and C57.BL/6) showed that there is an increase in phloxine-tartrazine positive cells following infection with T. spiralis. Although most striking in the duodenum, the increase in phloxine-tartrazine positive cells occurred along the entire length of the small intestine and peaked at days 8–21 after infection. In addition to an increase at the crypt base, tartrazine-positive cells were also seen in the upper portion of crypts and on the lateral aspects and tips of villi. Because Paneth cells are normally only present at the crypt base [4], further studies were performed by electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry to characterize the phloxine tartrazine-positive cells in the infected mice.

Ultrastructural studies showed that the phloxine-tartrazine-positive cells in the upper portion of crypts, and some also at the crypt base, had morphological features of intermediate cells containing characteristic secretory granules with electron-dense cores [5,30]. Such cells have been described in normal mice over many years, and have been considered by some to be transitional cells or cells intermediate between Paneth and goblet cells [5]. Others have suggested that they are an independent cell type functionally distinct from goblet and Paneth cells [33]. The intermediate cells in T. spiralis-infected mice are immunoreactive for cryptdin but not ITF. Since the expression of cryptdin and ITF is normally confined to Paneth cells and goblet cells, respectively, our studies suggest that the phloxine-tartrazine positive intermediate cells in the infected mice functionally bear a closer relationship to Paneth cells. In normal adult mice, intermediate cells occur above the stem cell zone [34], and it is likely that T. spiralis induces an expansion of this population of cells. One explanation for our findings is that infection with T. spiralis induces stem cells to differentiate preferentially along the lineages of Paneth cells and intermediate cells. In contrast to Paneth cells (which migrate to the base of crypts), the presence of intermediate cells on the lateral aspect and tips of villi suggests that their route of migration and ultimate loss into the lumen is similar to that of enterocytes and goblet cells.

Previous studies using Alcian blue PAS showed that goblet cells accumulate in the T. spiralis infection model [26]. Since we showed that the intermediate cells are strongly Alcian blue PAS positive, studies were performed to determine whether the previously described increase in goblet cell numbers in T. spiralis-infected mice was indeed due to an increase in intermediate cells. Immunohistochemical studies using antiserum to ITF (which is expressed by goblet cells but not intermediate cells, see above) confirmed that there is an increase in the number, as well as size, of goblet cells in T. spiralis-infected mice.

Goblet cell accumulation in T. spiralis-infected rodents has previously been shown to be likely to be dependent on T cells [26]. In the studies described above, T. spiralis-induced Paneth and intermediate cell accumulation was partially reversed by treatment with cyclosporin, implying that T cells contribute to this process. The increase in Paneth and intermediate cells was also seen in athymic (nude) mice infected with the nematode but not in TCR(β/δ)−/– mice. Transfer of MLNCs from infected wild-type C57.BL/6 mice led to an increase in Paneth and intermediate cells in TCR(β/δ)−/– mice. These epithelial cell changes also occurred after transfer of CD4-positive MLNCs (data not shown). Taken together, our studies suggest that a unique population of mucosal T cells induces the increase in Paneth and intermediate cell numbers following infection with T. spiralis. Such cells may have arisen from cryptopatches [35]. Transfer of cryptopatches from nude mice to irradiated SCID mice has been shown to lead to the development of CD4- and CD8-positive T cells expressing α/β and γ/δ T-cell receptors [35]. Our findings imply that the cells regulating the increase in Paneth and intermediate cells in T. spiralis infection are likely to be thymic-independent mucosal T cells derived from cryptopatches.

The present and previous studies suggest that during infection with T. spiralis, mucosal T cells may induce stem cells to differentiate preferentially into goblet, Paneth and intermediate cells. The subsequent change in the surface epithelium is likely to enhance host intestinal defence. Goblet and Paneth cells have been shown to be important in this process via their secreted products. In vivo, the release of these products into the intestinal lumen can be enhanced either by increased synthesis/secretion per cell, or via an increase in the total number of these cells. Both of these mechanisms appear to be operative in the T. spiralis-infection model. Increased secretion of mucin and ITF by goblet cells would be expected to enhance protection at the mucosal surface and may be responsible for the lack of ulceration, despite the fact that the parasite can invade and induce epithelial cell death [36,37]. Enhanced secretion of Paneth cell products such as cryptdins and other antimicrobial proteins (such as lysozyme and phospholipase A2) would also be expected to contribute to mucosal defence. Whether the Paneth cell-derived products mediate an effect on the nematode itself has not been determined. Since the expelled worms remain viable and can re-establish in the intestine when orally administered to naïve mice, it is possible that the increase in Paneth and intermediate cells contributes to changes in the small intestinal luminal environment, to one that is hostile to the worms and thereby facilitating their expulsion. In addition, changes in the small intestinal epithelium may affect fecundity of the worms. It is also conceivable that the Paneth and intermediate cell response is related to changes in the microbial composition of the small intestinal lumen resulting from a worm-altered microenvironment.

In conclusion, in addition to an increase in goblet cell numbers, the number of Paneth and intermediate cells increases in the small intestine of mice infected with T. spiralis. The intermediate cells expressed the Paneth cell-specific cryptdins but not the goblet cell-specific ITF. Studies in nude and TCR(β/δ)−/– mice have shown that a unique, likely thymic-independent population of mucosal T lymphocytes regulates the changes in Paneth and intermediate cells to enhance innate immunity in the intestinal mucosa.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the University of Nottingham and the Medical Research Council (UK).

References

- 1.Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. Am J Anat. 1974;141:537–62. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potten CS. Stem cells in the gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Phil Trans R Soc Lond. 1998;353:821–30. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stappenbeck TS, Wong MH, Saam JR, Mysorekar IU, Gordon JI. Notes from some crypt watchers: regulation of renewal in the mouse intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:702–9. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng H. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine IV. Paneth cells. Am J Anat. 1974;141:521–36. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troughton WD, Trier JS. Paneth and goblet cell renewal in mouse duodenum. J Cell Biol. 1969;41:251–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paterson JC, Watson SH. Paneth cell metaplasia in ulcerative colitis. Am J Pathol. 1961;38:243–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunliffe R, Rose FRAJ, Keyte J, Abberley L, Chan WC, Mahida YR. Human defensin 5 is stored in precursor form in Paneth cells and is expressed by some villous epithelial cells and by metaplastic Paneth cells in the colon in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48:178–85. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon JI. Understanding gastrointestinal epithelial cell biology: lessons from mice with help from worms and flies. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:315–24. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90703-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamont JT. Mucus: the front line of intestinal mucosal defense. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;664:190–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb39760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podolsky DK, Lynch-Devaney K, Stow JL, et al. Identification of human intestinal trefoil factor. Goblet cell-specific expression of a peptide targeted for apical secretion. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6694–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kindon H, Pothoulakis C, Thim L, Lynch-Devaney K, Podolsky DK. Trefoil peptide protection of intestinal epithelial barrier function: cooperative interaction with mucin glycoprotein. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:516–23. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dignass A, Lynch-Devaney K, Kindon H, Thim L, Podolsky DK. Trefoil peptides promote epithelial migration through a transforming growth factor β-independent pathway. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:376–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI117332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mashimo H, Wu D-C, Podolsky DK, Fishman MC. Impaired defense of intestinal mucosa in mice lacking intestinal trefoil factor. Science. 1996;274:262–5. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.262. 10.1126/science.274.5285.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keshav S, Lawson L, Chung LP, Stein M, Perry VH, Gordon S. Tumor necrosis factor mRNA localized to Paneth cells of normal murine intestinal epithelium by in situ hybridization. J Exp Med. 1990;171:327–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan X, Hseuh W, Gonzalez-Crussi F. Cellular localization of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α transcripts in normal bowel and in necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1858–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen SS, Nexo E, Olsen PS, Hess J, Kirkegaard P. Immunohistochemical localization of epidermal growth factor in rat and human. Histochemistry. 1986;85:389–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00982668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Sauvage FJ, Keshav S, Kuang WJ, Gillett N, Henzel W, Goeddel DV. Precursor structure, expression and tissue distribution of human guanylin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9098–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson CL, Heppner KJ, Rudolph LA, Matrisian LM. The metalloproteinase matrilysin is preferentially expressed by epithelial cells in a tissue-restricted pattern in the mouse. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:851–69. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwig SSL, Tan L, Qu X, Cho Y, Eisenhauer PB, Lehrer RI. Bactericidal properties of murine intestinal phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:603–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI117704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erlandsen SL, Parsons JA, Taylor TD. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of lysozyme in the Paneth cells of humans. Histochem Cytochem. 1974;22:401–13. doi: 10.1177/22.6.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selsted ME, Miller SI, Henschen AH, Ouellette AJ. Enteric defensins: antibiotic components of intestinal host defense. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:929–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.4.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cells and innate immunity in the crypt microenvironment. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1779–84. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson CL, Ouellette AJ, Satchell DP, et al. Regulation of intestinal α-defensin activation by the metalloproteinase matrilysin in innate host defense. Science. 1999;286:113–7. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5437.113. 10.1126/science.286.5437.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson A, Jarrett EE. Hypersensitivity reactions in the small intestine. I. Thymus dependence of experimental ‘partial villous atrophy’. Gut. 1975;16:114–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garside P, Grencis RK, Mowat MACI. T lymphocyte dependent enteropathy in murine Trichinella spiralis infection. Parasite Immunol. 1992;14:217–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1992.tb00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa N, Wakelin D, Mahida YR. Role of T helper 2 cells in intestinal goblet cell hyperplasia in mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:542–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts SJ, Smith AL, West AB, et al. T-cell alphabeta+ and gammadelta+ deficient mice display abnormal but distinct phenotypes toward a natural, widespread infection of the intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1774–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakelin D, Lloyd M. Immunity to primary and challenge infections of Trichinella spiralis in mice: a re-examination of conventional parameters. Parasitology. 1976;72:173–82. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000048472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subbuswamy SG. Paneth cells and goblet cells. J Pathol. 1973;111:181–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1711110306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garabedian EM, Roberts LLJ, McNevin MS, Gordon JI. Examining the role of Paneth cells in the small intestine by lineage ablation in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23729–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23729. 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakelin D, Wilson MM. T and B cells in the transfer of immunity against Trichinella spiralis in mice. Immunology. 1979;37:103–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishikawa N, Goyal PK, Mahida YR, Li KF, Wakelin DW. Early cytokine responses during intestinal parasite infections. Immunology. 1998;93:257–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calvert R, Bordeleau G, Grondin G, Vezina A, Ferrari J. On the presence of intermediate cells in the small intestine. Anat Rec. 1988;220:291–5. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjerknes M, Cheng H. The stem-cell zone of the small intestinal epithelium. III. Evidence from columnar, enteroendocrine, and mucous cells in the adult mouse. Am J Anat. 1981;160:77–91. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito H, Kanamori Y, Takemori T, et al. Generation of intestinal T cells from progenitors residing in gut cryptopatches. Science. 1998;280:275–8. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.275. 10.1126/science.280.5361.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunn IJ, Wright KA. Cell injury caused by Trichinella spiralis to the mucosal epithelium of BIOA mice. J Parasitol. 1983;71:757–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li KF, Seth R, Gray T, Bayston R, Mahida YR, Wakelin D. Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators in human intestinal epithelial cells after invasion by Trichinella sp1iralis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2200–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2200-2206.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]