Abstract

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the most frequently occurring primary immunodeficiency in both children and adults. The molecular basis of CVID has not been defined, and diagnosis involves exclusion of other molecularly defined disorders. X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP) is a rare disorder in which severe immunodysregulatory phenomena typically follow Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. Boys who survive initial EBV infection have a high incidence of severe complications, including progressive immunodeficiency, aplastic anaemia, lymphoproliferative disease and lymphoma. Survival beyond the second decade is unusual, although bone marrow transplantation can be curative. Until recently reliable diagnostic testing for XLP has not been available, but the identification of the XLP gene, known as SH2D1A, and coding for a protein known as SAP, means that molecular diagnosis is now possible, both by protein expression assays, and mutation detection, although the mutation detection rate in several series is only 55–60%. We describe three male patients initially diagnosed as affected by CVID, one of whom developed fatal complications suggestive of XLP, and all of whom lack expression of SAP. Two out of three have disease-causing mutations in the SAP gene, consistent with published data for XLP. These findings raise the possibility that a subgroup of patients with CVID may be phenotypic variants of XLP. Further studies are necessary to investigate this possibility, and also to clarify the prognostic significance of SAP abnormalities in such patients in the absence of typical features of XLP.

Keywords: immunodeficiency, lymphoproliferative disease, Epstein–Barr virus

Introduction

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the most common primary immunodeficiency, and is usually diagnosed in adolescence or young adulthood, although younger children can be affected [1]. CVID is characterized by low levels of at least two of the three major immunoglobulin isotypes, abnormal specific antibody production, and variable T and B cell numbers. Patients present with recurrent sinopulmonary or other infections, autoimmune phenomena and gastrointestinal disease [2]. CVID is highly heterogeneous, with an unpredictable inheritance pattern. In a few patients mutations in the genes responsible for X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) [3] or X-linked Hyper-IgM syndrome (XHM) have been found. Genetic linkage studies have also suggested linkage to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [4]. However, the genetic basis in most cases of CVID remains unknown.

X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP, Duncan's disease) [5] is a rare disorder in which severe immunodysregulatory phenomena occur typically after exposure to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), although in a few cases EBV has not been implicated [6–8]. Clinical manifestations are variable. Severe, often fatal, infectious mononucleosis is the most usual presentation (58%), and boys who survive the initial exposure to EBV may develop dysgammaglobulinaemia (31%), or lymphoma, usually of B cell origin (30%). Less frequent complications include aplastic anaemia, lymphoid granulomatosis and necrotizing vasculitis [6]. Survival beyond the second decade of life is unusual, although successful bone marrow transplantation (BMT) has been reported [9,10]. Diagnosis of XLP has, until recently, depended on a suggestive phenotype, sometimes with an X-linked pedigree. In some of these pedigrees linkage analysis has defined high-risk haplotypes [11]. In cases where a single male manifests an XLP phenotype and in atypical cases without EBV infection, the diagnosis is even more uncertain [12]. Affected boys are usually asymptomatic before exposure to EBV or other triggers, although minor immunoglobulin abnormalities have been described [7].

The XLP gene, identified in 1998, codes for a protein known as SAP (SLAM-associated protein, where SLAM is ‘signalling lymphocyte activation molecule’) [13,14]. SAP is expressed predominantly in T and NK cells, and is thought to act as a molecular switch regulating pathways involved in stimulation of T and NK cell cytotoxicity [15,16]. Abnormalities of SAP expression or function may lead to an uncontrolled immune response to EBV or other viruses as a result of dysregulation of this pathway.

Precise diagnosis of XLP by mutation analysis is now possible in many families, but the mutation detection rate using SSCP analysis in boys with typical XLP is only 55–65% in several series [13,14,17], lower than in other disorders, where the sensitivity of SSCP is 85–90%. The reasons for this are unclear, but significant numbers of cases remain unconfirmed. One series, however, reports a 95% detection rate [18]. Recently analysis of SAP expression in T cells has been shown to be a reliable diagnostic technique [19]. Absence of SAP has also been demonstrated in several cases of typical XLP where no mutation was found.

We describe three boys who were initially diagnosed with CVID, but who have been found to lack SAP expression. One boy developed fatal complications associated with EBV infection while the other two remain well at present on immunoglobulin therapy.

Case histories

All three boys were/are under the care of the department of Immunology at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London.

Case 1

Case 1 was the first child of unrelated parents with no family history of immunodeficiency. He was fully immunized without complications and was well until the age of four, when he had severe haemophilus influenzae meningitis. Subsequently recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections required frequent antibiotics. At nine years of age he had a persistent productive cough, and a chest CT scan showed bilateral basal bronchiectasis. Ciliary function and sweat tests were normal. Immunological investigation showed panhypogammaglobulinaemia with CD4:CD8 ratio reversal (Table 1) consistent with CVID. He received regular intravenous immunoglobulin with considerable improvement in his respiratory symptoms. After this he was well for three years although there was a progressive reduction in B cell numbers. Molecular investigation excluded X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) and X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome (XHM) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Immunological and virological investigations

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 years | 14 years | 7 years | 8 years | 9 years | 12 years | |

| Absolute LC × 109/l (NR) | 2·92 (1·0–5·3) | 0·79 (1·0–5·3) | 2·59 (1·1–5·9) | 2·36 (1·1–5·9) | 2·32 (1·1–5·9) | 1·69 (1·0–5·3) |

| CD3 × 109/l (NR) | 2·34 (0·8–3·5) | 0·75 (0·8–3·5) | 2·15 (0·7–4·2) | 1·96 (0·7–4·2) | 1·69 (0·7–4·2) | 1·25 (0·8–3·5) |

| CD4 × 109/l (NR) | 0·91 (0·4–2·1) | 0·46 (0·4–2·1) | 0·83 (0·3–2·0) | 0·71 (0·3–2·0) | 0·56 (0·3–2·0) | 0·44 (0·4–2·1) |

| CD8 × 109/l (NR) | 1·37 (0·2–1·2) | 0·28 (0·2–1·2) | 1·04 (0·3–1·8) | 1·01 (0·3–1·8) | 0·97 (0·3–1·8) | 0·44 (0·2–1·2) |

| CD19 × 109/l (NR) | 0·32 (0·2–0·6) | U/D (0·2–0·6) | 0·01 (0·2–1·6) | 0·05 (0·2–1·6) | 0·35 (0·2–1·6) | 0·18 (0·2–0·6) |

| PHA (SI) | 468 | 19·8 | 49·7 | 98·9 | 62·6 | 41·8 |

| IgG (g/l) | < 0·51 | 9·03* | 0·83 | 7·5* | 1·15 | 9·8* |

| IgA (g/l) | < 0·11 | < 0·06 | < 0·06 | < 0·06 | < 0·03 | < 0·06 |

| IgM (g/l) | < 0·06 | < 0·04 | < 0·04 | < 0·04 | < 0·04 | < 0·04 |

| Hib abs | Absent | – | Absent | – | Absent | – |

| Tetanus abs | Absent | – | Absent | – | Absent | – |

| Pneumo abs | Absent | – | Absent | – | Very low | – |

| EBV serology | Neg | – | Neg | – | Neg | – |

| EBV PCR | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | – | Neg |

NR: normal range; U/D: undetectable.

On immunoglobulin replacement.

PHA normal range: Stimulation Index (SI) ≥ 100. Normal range derived from 150 normal adults (geometric mean SI = 288, 2 standard deviations below mean = 115).

Table 2.

Molecular investigations

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | BTK | Normal | Normal | ND |

| CD40L | Normal | Normal | ND | |

| SAP | Absent | Absent | Absent | |

| DNA | BTK | ND | Normal | ND |

| CD40L | ND | ND | ND | |

| SAP (SH2D1A) | Missense G39V | Intronic 5 bp deletion | No mutation found |

ND: not done.

At 13 years he developed mild neutropaenia, which progressed over a year to pancytopaenia. Bone marrow aspirate showed striking hypocellularity, increased macrophage numbers and very occasional haemophagocytic activity. He was treated initially with steroids for aplastic anaemia, but within a month developed jaundice and hepatitis. A severe coagulopathy was complicated by retinal and vitreous haemorrhages causing near total blindness, and intracranial haemorrhages resulting in severe hearing loss. High fevers, chest CT scan, and sinus opacification suggested fungal invasion. EBV DNA was detected in the plasma by PCR for the first time at this point. Antibiotics, antifungals and ganciclovir were ineffective in improving his clinical condition.

A diagnosis of EBV-induced haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytic (HLH) was made and he was treated with etoposide (VP16) and steroids according to the standard UK HLH protocol. After a poor response he received a five day course of antithymocyte globulin but continued to deteriorate. Further treatment with conditioning chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation was not considered appropriate. He died shortly afterwards.

Case 2

Case 2 is an eight-year-old boy, the second child of unrelated Russian parents with no family history of immunological disorders. He was born in Russia, and at four months of age developed suppurative cervical lymphadenitis requiring incision and drainage. Subsequently generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly were noted.

From four years he had recurrent episodes of otitis media and respiratory infections. Investigation in Russia showed panhypogammaglobulinaemia and mild lymphopenia. No further evaluation was performed. He was treated with ‘bio-stimulators’, but his infections continued, with an episode of arthritis at the age of seven, when he came to the UK. He was unwell and emaciated, his weight being at the 0·4th centile and height on the 9th centile. He had widespread lymphadenopathy, discharging otitis media, left basal pneumonia and osteomyelitis of the left femur. MRI scan confirmed a bone abscess, but culture of biopsy material was negative. A prolonged course of intravenous and oral antibiotics led to complete resolution of the infections.

Immunological investigation showed panhypogammaglobulinaemia, with very low circulating B cells (Table 1). He was started on intravenous immunoglobulin, with a tentative diagnosis of XLA. However, ‘btk’ (Bruton's tyrosine kinase) expression was normal, and no mutation was detected in the ‘btk’ gene. CD154 (CD40 ligand) expression was also normal, excluding X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome (XHM) (Table 2). Currently he remains well on subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement.

Case 3

Case 3 is a 13-year-old boy, who was well until three years when he developed recurrent otitis media requiring frequent oral antibiotics and insertion of grommets on four occasions. He was fully immunized without problems. There was no family history suggestive of X-linked immunodeficiency. At nine years he developed a chronic cough and persistent right mid-zone pneumonia. Further investigation showed panhypogammaglobulinaemia and a reversed CD4:CD8 ratio (Table 1), suggestive of CVID. He commenced intravenous immunoglobulin with significant improvement of his chest symptoms, and is currently well on immunoglobulin.

Methods

SAP expression analysis and SAP mutation screening

SAP expression analysis was performed by immunoblotting of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and mutation screening was performed by initial SSCP analysis of PCR amplified genomic DNA using SH2D1A-specific primers, followed by sequencing of abnormal exons, all as described by Gilmour [19]. mRNA purification from Case 2, Case 3 and controls was also as in Gilmour [19], and SAP cDNA was amplified using SAP specific primers as decribed by Sayos [15].

Results

Immunology and virology

Results of investigations in the three boys at presentation and most recently are shown in Table 1. All three had severe panhypogammaglobulinaemia at diagnosis. Case 2 had extremely low circulating B cells at presentation, while Case 1 progressively lost B cells over a three year period and Case 3 has so far maintained normal B cells. All three had CD4:CD8 ratio reversal, although in Case 1 this normalized, and in Case 3 improved with time. EBV serology was negative in all three, not surprising in view of the severe hypogammaglobulinaemia and lack of other specific antibody responses. EBV PCR testing on plasma became positive in Case 1 only after he had developed HLH, while EBV PCR analysis remains negative in the other two boys.

Molecular analysis

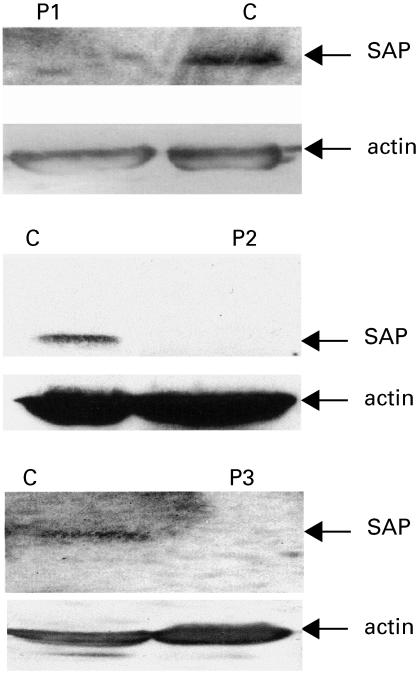

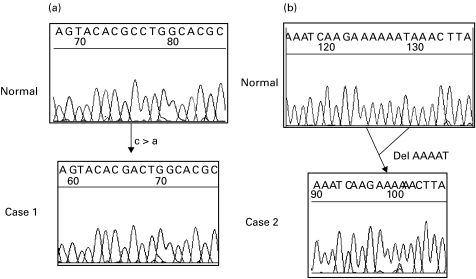

Molecular investigations excluded XLA and CD40 ligand deficiency in Cases 1 and 2, but were not performed in Case 3 because his phenotype did not suggest either of these diagnoses (Table 2). SAP expression analysis performed during the final illness in Case 1 confirmed absence of SAP in mononuclear cells (Fig. 1). Subsequently a missense mutation was identified in the SH2D1A gene (Fig. 2a). This mutation results in a single amino-acid substitution (glycine to valine, G39V) at the beginning of a beta-pleated sheet in a highly conserved region of the SAP protein, and would be predicted to disrupt protein folding at this crucial point. The same mutation is present in his mother, but not in his maternal grandmother, or in 100 normal X chromosomes. These findings are highly suggestive that the mutation is disease causing, and, in combination with absence of SAP expression, confirm a diagnosis of X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome.

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of SAP expression in Case 1, 2 and 3. C: normal control; P1: Case 1; P2: Case 2; P3: Case 3. The SAP specific band is absent in all three affected boys. Normal actin specific bands are present in all affected boys and controls.

Fig. 2.

Sequencing data from Cases 1(a) and 2 (b). In Case 1 a single nucleotide substitution results in a single amino acid alteration (Glycine to Valine, G39V). In Case 2 a 5-bp intronic deletion (IVS3 − 28 to − 32 del ATTTT) probably leads to transcription of an unstable mRNA.

Case 2 has no detectable SAP protein (Fig. 1), and he has a 5 base pair deletion in intron 3 of the SH2D1A gene (Fig. 2b). Although this mutation does not affect the conserved sequence of the splice acceptor site, it may affect the branch point. 100 normal X chromosomes have been analysed and do not contain this deletion. cDNA analysis showed no SAP cDNA in Case 2 while the expected two bands were observed in control samples. β-Actin cDNA amplified normally from Case 2 and the control samples indicating that all samples had intact cDNA. This result is consistent with the intronic deletion affecting splicing and creating an unstable mRNA product.

Case 3 has been shown to lack SAP expression on multiple occasions (Fig. 1), but direct sequencing of the four exons and exon/intron boundaries of the SH2D1A gene has not revealed a mutation, and normal SAP mRNA is also present (data not shown).

Discussion

CVID is an heterogeneous disorder for which the genetic basis is unknown in most cases. A wide variety of complications can be associated with CVID, including lymphoproliferative disease and lymphoma [2], although these occur in a minority of patients, and life expectancy in CVID is usually well into adulthood. By contrast, typical XLP is very rare and is associated with a very poor outlook, survival beyond adolescence without BMT being unusual [6]. However, the clinical manifestations in XLP are variable, and the association with EBV is not absolutely consistent [8]. Diagnosis has historically been hampered by lack of a specific test, and SH2D1A mutation analysis has only allowed confirmation in 55–60% of cases in several series [13,14,17], although Sumegi [18] reports a 95% detection rate. SAP expression analysis provides a quick and specific diagnostic test, which has so far proved highly reliable in classical XLP [19].

All three cases described presented in early childhood and fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for CVID. None of them had a family history suggestive of an X-linked disorder. There was no early history suggestive of EBV infection, and both serology and PCR testing were negative in all except Case 1 who became PCR positive during his final illness. XLP was considered in Case 1 when he developed an HLH-like syndrome following a period of bone marrow aplasia, and was confirmed by the findings of absent SAP expression and a disease-causing mutation. The other two boys were subsequently also found to lack SAP expression, and a mutation confirmed in Case 2. Although no mutation has been found in Case 3, we believe that absence of SAP represents a primary abnormality. SAP expression analysis in a wide range of other situations, including normal controls, other EBV-infected children, children with severe sepsis, and children affected by other immunodeficiencies, has in all cases been normal [19]. The mutation pick-up rate of 2/3 in this group is consistent with the overall 55–60% detection rate in other series of typical XLP. Possible explanations for the failure to detect mutations in some patients include defects in promotor or other transcriptional control genes, or insensitivity of the SSCP technique.

These observations raise the possibility of SAP abnormalities in other male patients affected by CVID, and of significant phenotypic variation in XLP. One of the three boys developed typical complications of XLP, but the other two at present have no evidence of EBV infection or other complications. Although typical XLP is associated with severe complications and a poor outlook, phenotypic variation may mean that some patients have a better outlook, without the need for aggressive intervention such as BMT. This spectrum of clinical phenotypes is well described in other primary immunodeficiencies, including XLA [20], CD40 ligand deficiency [21] and Wiskott Aldrich syndrome. An extensive study of the frequency of SAP mutations in males with CVID, along with an assessment of associated clinical phenotype, is necessary before the significance of these findings can be assessed. Such a study is planned in the near future.

Precise molecular definition would allow screening of other at risk males, and carrier testing for female family members. Early diagnosis in asymptomatic affected males would allow early immunoglobulin prophylaxis – although this may be of limited value – and consideration for early BMT. Prenatal diagnosis would also be available. Assessment of the appropriateness of such interventions will depend on further definition of the significance of SAP abnormalities in the absence of typically affected family members. Intra-familial phenotypic variation, as is well described for XLA [22], may also need consideration when managing these families.

In summary, we have demonstrated absent SAP expression in three boys originally diagnosed with CVID. SAP mutations have been found in two out of three, and one of these two developed fatal complications typical of XLP. Further studies are needed to evaluate the frequency of SAP abnormalities in CVID, and to establish the significance of such findings in order to offer optimal management to affected families.

Acknowledgments

This work was undertaken by Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust, which received a portion of its funding from the NHS Executive. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS Executive.

References

- 1.Conley ME, Notarangelo LD, Etzioni A. Diagnostic criteria for primary immunodeficiencies. Representing PAGID (Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiencies) Clin Immunol. 1999;93:190–7. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:34–48. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4725. 10.1006/clim.1999.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanegane H, Tsukada S, Iwata T, et al. Detection of Bruton's tyrosine kinase mutations in hypogammaglobulinaemic males registered as common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) in the Japanese Immunodeficiency Registry. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:512–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01244.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vorechovsky I, Cullen M, Carrington M, Hammarstrom L, Webster AD. Fine mapping of IGAD1 in IgA deficiency and common variable immunodeficiency: identification and characterization of haplotypes shared by affected members of 101 multiple-case families. J Immunol. 2000;164:4408–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purtilo DT, Cassel CK, Yang JP, Harper R. X-linked recessive progressive combined variable immunodeficiency (Duncan's disease) Lancet. 1975;1:935–40. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seemayer TA, Gross TG, Egeler RM, et al. X-linked lymphoproliferative disease: twenty-five years after the discovery. Pediatr Res. 1995;38:471–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grierson HL, Skare J, Hawk J, Pauza M, Purtilo DT. Immunoglobulin class and subclass deficiencies prior to Epstein–Barr virus infection in males with X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Am J Med Genet. 1991;40:294–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strahm B, Rittweiler K, Duffner U, et al. Recurrent B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in two brothers with X-linked lymphoproliferative disease without evidence for Epstein–Barr virus infection. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:377–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01884.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross TG, Filipovich AH, Conley ME, et al. Cure of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP) with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): report from the XLP registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:741–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann T, Heilmann C, Madsen HO, Vindelov L, Schmiegelow K. Matched unrelated allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for recurrent malignant lymphoma in a patient with X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP) Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:603–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuster V, Seidenspinner S, Grimm T, Kress W, Zielen S, Bock M, Kreth HW. Molecular genetic haplotype segregation studies in three families with X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:432–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01983408. 10.1007/s004310050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grierson HL, Skare J, Church J, et al. Evaluation of families wherein a single male manifests a phenotype of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP) Am J Med Genet. 1993;47:458–63. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffey AJ, Brooksbank RA, Brandau O, et al. Host response to EBV infection in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease results from mutations in an SH2-domain encoding gene. Nat Genet. 1998;20:129–35. doi: 10.1038/2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols KE, Harkin DP, Levitz S, et al. Inactivating mutations in an SH2 domain-encoding gene in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13765–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13765. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayos J, Wu C, Morra M, et al. The X-linked lymphoproliferative-disease gene product SAP regulates signals induced through the co-receptor SLAM. Nature. 1998;395:462–9. doi: 10.1038/26683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tangye SG, Lazetic S, Woollatt E, Sutherland GR, Lanier LL, Phillips JH. Cutting edge: human 2B4, an activating NK cell receptor, recruits the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 and the adaptor signaling protein SAP. J Immunol. 1999;162:6981–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin L, Ferrand V, Lavoue MF, et al. SH2D1A mutation analysis for diagnosis of XLP in typical and atypical patients. Hum Genet. 1999;105:501–5. doi: 10.1007/s004390051137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumegi J, Huang D, Lanyi A, et al. Correlation of mutations of the SH2D1A gene and Epstein–Barr virus infection with clinical phenotype and outcome in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2000;96:3118–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilmour KC, Cranston T, Jones A, et al. Diagnosis of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease by analysis of SLAM-associated protein expression. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1691–7. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1691::AID-IMMU1691>3.0.CO;2-K. 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1691::AID-IMMU1691>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto S, Miyawaki T, Futatani T, et al. Atypical X-linked agammaglobulinemia diagnosed in three adults. Intern Med. 1999;38:722–5. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.38.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy J, Espanol-Boren T, Thomas C, et al. Clinical spectrum of X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. J Pediatr. 1997;131:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornfeld SJ, Haire RN, Strong SJ, Brigino EN, Tang H, Sung SS, Fu SM, Litman GW. Extreme variation in X-linked agammaglobulinemia phenotype in a three-generation family. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:702–6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]