Abstract

As the effects of vitamin D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2-D3) (VD, calcitriol) on the proliferation and differentiation potential of normal and leukaemic cells in vitro of myeloid lineage are known, we investigated the response to VD on the growth of both normal and malignant lymphoid progenitors. Effects of vitamin D on normal human lymphoid progenitors and B lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) progenitors were assessed by using an in vitro cell colony assay specific for either B or T cell lineages. The expression of VDR on B untreated malignant progenitors at diagnosis was investigated by RT-PCR analysis. VD induced a significant inhibition of normal lymphoid cell progenitors growth of both T and B lineage. VD inhibited significantly also the growth of malignant B cell lineage lymphoid progenitors, without inducing cytotoxic effect. As it has been reported that VD effects on activated lymphocytes are mediated by 1,25-(OH)2-D3 nuclear receptor (VDR), we investigated VDR expression on malignant B cell progenitors. We did not detect VDR expression on these cells examined at diagnosis. We demonstrated that VD inhibited in vitro the clonogenic growth of both normal and malignant lymphoid B cell progenitors and that this inhibitory effect on malignant B cell progenitors was not related to VDR. Our work contributes to understanding of the mechanism of action of this hormone in promoting cellular inhibition of clonal growth of malignant lymphoid B cell progenitors, suggesting that the regulation of some critical growth and differentiation factor receptors could be a key physiological role of this hormone.

Keywords: 1, 25-(OH)2-D3; colony assay; lymphoid progenitors; vitamin D receptor

Introduction

The dihydroxylated form of vitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2-D3), as an immunohaematopoietic regulatory hormone, has been investigated extensively in the past few years. Most of the biological actions of VD are now thought to be exerted through the nuclear VD receptor (VDR)-mediated control of target genes. VDR belongs to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily and acts as a ligand-inducible transcription factor [1].

VD is able to induce differentiation in several haematological cells and may play an immunomodulating role in cellular proliferation for a number of malignant cell types [2]. In particular, previous studies suggested that myeloid precursors at all stages of differentiation are equipped with the machinery required to trigger a VD-dependent genetic programme, leading eventually to terminal differentiation [3]. In other words, they contain VDR protein that is fully active in binding their DNA sites and in promoting transcription [3].

To gain some insight into the VD activity on lymphoid lineage, we studied the effect of this hormone on the growth of normal and malignant lymphoid progenitors, by using an in vitro cell colony assay specific for either B or T cell lineages and investigated the expression of VDR on B untreated malignant progenitors.

Our work showed that VD significantly inhibited the growth of normal and malignant lymphoid progenitors without inducing a cytotoxic effect. As we did not detect VDR expression on leukaemic blast cells examined at diagnosis, our data indicate that VD inhibitory effect on these cells is not related to VDR.

Materials and methods

Normal and patient samples

Ten normal subjects and 10 B lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) patients, age ranging from 2 to 10 years, were included in the study. Diagnosis of B lineage ALL was performed on the basis of morphological, cytochemical and immunological surface marker profiles of marrow blasts, according to the French–American–British (FAB) criteria [4] and Italian–Berlin–Frankfurt–Muenster Study Group (I-BFM-SG) [5]. All cases were classified as B cell precursor ALL (BCP-ALL), either common ALL (CD19+, HLA-DR+, CD10+, CyIgM, six cases) or pre-B ALL (CD19+, HLA-DR+, CD10 +, CyIgM+, four cases). Two B lineage leukaemic cell lines, Nalm 6 and REH, were available from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures Department of Human and Animal Cell Cultures, Mascheroder Weeg 1b, Germany) and were maintained in RPMI-1640 tissue culture medium (Gibco, Milano, Italy) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco)

Cell separation

Mononuclear cells (MNC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Uppsala, Sweden). Subsequently, MNC were depleted of adherent cells by 2 h incubation in α-MEM (Gibco) with 20% of FCS (Gibco) at 37°C, followed by collection of non-adherent cells by gentle pipetting. To isolate T and B cells, E rosette-forming T lymphocytes were removed by rosetting MNC with 2-aminoethylisothio uronium bromide (AET) (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, USA)-treated sheep red blood cells (SRBC) and successive Ficoll separation [6]. The B cell-enriched population contained < 0·5% E rosette-forming T cells. E rosette-enriched cells were collected from the pellet after hypotonic lysis of the SRBC. The purity of both populations was evaluated by flow cytometry (FACScan instrument and Cell Quest software: Becton Dickinson). The technique of lymphocyte gating was performed by combining the light-scattering gate and the expression of human leucocyte antigen CD45 conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE; Caltag Laboratories; Burlingame, CA, USA) to differentiate lymphocytes. The B cell-enriched population was incubated with Leu-12 (anti-CD19) monoclonal antibody (MoAb) conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Caltag Laboratories) and CD45. The T cell population was incubated with anti-CD3-FITC (Leu4, Becton Dickinson) and CD45-PE. They contained 91% of CD45/CD19+ cells and more than 92% of CD45/CD3+ cells, respectively.

Colony assay

We have reported previously the different biological properties of normal B and T cell precursors [7]. The method of Izaguirre et al. [8] was used for B cell colony assay, as described previously [7,9–11]. In brief, 2 × 105 cells from the E− cell fraction were seeded in 0·8% methylcellulose in minimal essential medium (MEM), supplemented with 10% FCS, 20% of a T conditioned medium (PHA-TCM) and 3 × 105 irradiated T lymphocytes, obtained from two normal donors. Conditioned medium by PHA-stimulated purified T lymphocytes was obtained by incubating purified T lymphocytes at a concentration of 106/ml for 3 days. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 days in a moist atmosphere under hypoxaemic conditions (7% O2 in air). For T colony assay, medium conditioned by PHA-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) (PHA-LCM) was prepared by incubating 106/ml PBL and used as source of growth factors. Cells (2 × 105) obtained from the E+ cell fraction were seeded in 0·8% methylcellulose in MEM, supplemented with 10% FCS and 20% of PHA-LCM. Cultures were incubated for 5 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. The same T lymphocyte donors and PHA-CM batch were used throughout this study.

Treatment of cells with 1,25-(OH)2-D3

VD was dissolved in absolute ethanol at 10−3 mol/l in order to create a stock solution that was then protected from light and stored at − 20°C. Further dilutions of the stock solution were made in MEM without FCS. A dose–response curve was performed by testing different VD concentrations (from 10−11 to 10−6) on the population of enriched B and T cell precursors. We added VD alone or in association with the conditioned medium to the test wells at final concentration of 10−6m. In control wells, absolute ethanol was added at a concentration equivalent to that present in the highest concentration of VD (0·01%).

Characterization of colony forming cells

Aggregates containing > 20 and > 50 cells, respectively, were counted as B and T colonies under an inverted microscope. Colonies were drawn up with a fine capillary pipette containing cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pooled and washed for further morphological and immunological characterization, as described previously [7,9–11]. In colony-forming units (CFU)-B lineage the colony-forming cells (CFC) were phenotyped for the presence of CD10 (J5, Instrumentation Laboratories, Coulter, Milan, Italy), HLA-DR (OKDR, Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Milan, Italy) and sIg (antihuman Ig F (antibody), Behring, L'Aquila, Italy) expression. In CFU-T lineage colonies the CFC were phenotyped for CD7 (Leu9, Becton Dickinson, Milan, Italy), CD3 (Leu4, Becton Dickinson) and CD38 (OKT10, Ortho Diagnostic Systems) expression. Isotypic controls were always added. Non-specific binding was prevented by incubation with AB serum.

Assesment of cytotoxicity and apoptosis

Cytotoxicity and apoptosis were evaluated by flow cytometry in two B lineage cell lines (Nalm-6 and REH) and two B cell precursor ALL, as described previously [12,13]. Cell lines and leukaemic samples were incubated for 48 and 72 h, respectively, with VD from 10−6 m to 10−8m.

At the beginning of the cultures, we set ‘gates’ around the area of the light-scatter dot plot that included virtually all blast cells. We used these gates to count cells with the predetermined light-scatter properties that were present after culture with and without VD. The formula (number of cells recovered with VD/number of cells recovered in parallel culture without VD) × 100 was used to calculate relative cell recovery after VD treatment. All results are reported as the mean of triplicate experiments. To detect the occurrence of apoptosis, we also measured cell labelling with FITC-conjugated Annexin-V (Bender MedSystems; MedSystems Diagnostics GmbH, A-1030 Vienna, Austria), which binds to phosphatidylserine exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells. To detect cell membrane permeabilization, cells were labelled with propidium iodide (5 mg/ml; Bender MedSystems) for 15 min at 20°C.

RNA analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted using a modification of the guanidium–caesium chloride centrifugation technique [14] and digested with RQ1-DNase (Promega, Madison, WT, USA) to avoid DNA contamination, as described previously [15]. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out using a modification of a previously described technique [15]. RT-PCR analysis was performed using an oligodeoxynucleotide primers specific for VDR [16,17] and β2 microglobulin (β2m) [18]. The oligonucleotides used as DPs or RPs were as follows: (a) VDR-DP (5-GGAGACTTTGACCGGAACGTG-3) and VDR-RP (5 GAACTGGCAGAAGTCGGAGTA-3); (b) VDR primary transcript-DP (5 –CAGTGACGTGACCAAAGGTATGCC TAG -3) and VDR primary transcript-RP (5-GGGAGACGATGCAGATGGCCATGAGCA-3); and (c) β2m-DP (5–CTCGCGCTACTCTCTCTTTCT-3) and β2m-RP (5–TCCATTCTTCAGTAAGTCAACT-3).

Results

Clonogenic responses of normal peripheral haematopoietic lymphoid precursors to VD

Ethanol, the vehicle for VD, had no effect on cell viability. The maximal inhibitory responsiveness to VD was observed at 10−6 m for both cell lymphoid populations, suggesting that, at this VD concentration, target cells presented the highest avidity to VDR. B and T cell progenitors from normal controls generated 54 ± 15·87 and 64·6 ± 30·9 colonies/105 cells, respectively, when PHA-TCM and PHA-LCM were used as the source of stimulation. The addition of calcitriol to the positive control showed a significant inhibition (P < 0·05) in both B and T lineage colonies (Table 1). PHA alone induced clusters that were not reduced significantly by the addition of calcitriol in both T and B lineage colonies.

Table 1.

Effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the growth of normal and malignant lymphoid progenitors

| Progenitor cells | Sample | Source of stimulation | Colonies/105 cells Mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-lineage | PB | None | 0 (0) |

| PHA-TCM | 54 (15.8) | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 0 (0) | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 + PHA-TCM | 12.7 (6.97) | ||

| T-lineage | PB | None | 0 (0) |

| PHA-LCM | 64.6 (30.1) | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 0 (0) | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 + PHA-TCM | 23.2 (7.89) | ||

| B-lineage ALL | BM | None | 2.1 (1) |

| PHA-TCM | 50 (8.5) | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 8.3 (3.5) | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 + PHA-TCM | 11.7 (3.1) |

PB: peripheral blood; BM: bone marrow; PHA-LCM: PHA-leucocyte conditioned medium; PHA-TCM: PHA-T lymphocytes conditioned medium.

Effect of VD on cell viability

To determine whether VD was cytotoxic against leukaemic cells we assessed light-scatter variations of pre- and post-VD-treated cell samples. Nalm 6 and REH cell lines showed 96·6 ± 1·2 and 68·5 ± 1·9% of viable cells, respectively, in the control versus 93·6 ± 0·8 and 68·1 ± 2·6% in the culture treated with VD at a concentration of 10−6m. Overlapping results were observed at the other tested concentrations (10−7m, 10−8m) and similarly in two B lineage ALL (Fig. 1). The investigation of apoptosis by labelled Annexin-V did not show any difference between control and following VD treatment in the two B lineage ALL samples, confirming the above results (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

VD cytotoxicity in one case of ALL as measured by flow cytometry. Panels (a) and (c) show side-scatter (SSC) versus forward-scatter (FSC) of leukaemic lymphoblasts after 48 h of culture without and with VD (10-7m), respectively. (b) and (d) Binding of fluorescein-Annexin-V after 48 h of culture without and with VD, respectively.

Clonogenic response of malignant B cell progenitors

Malignant B cell progenitors from ALL were cultivated in a semisolid assay at an optimal concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml. The addition of VD to the positive control showed a significant inhibition of the growth in B colony assays (mean: 50 ± 8·5 versus 11·7 ± 3·1; P < 0·05) (Table 1). Similar to that observed in normal B progenitors, the addition of calcitriol to PHA in the colony assay did not significantly reduced the clusters' number.

Characterization of colony-forming cells

Morphological examination of CFU from normal and neoplastic progenitors did not present any difference between control and VD-inhibited colonies, showing lymphoblastoid appearance in both cases. Immunophenotypic analysis of pooled colony-forming cells (CFC) from normal T and B cell progenitors indicated the presence of mature markers of B and T cell lineage both in PHA-CM-induced colonies (positive control) and in calcitriol-inhibited assays. Immunophenotypic analysis of pooled CFC from two B lineage ALL patients did not show any differentiation effect by confirming the immunological characterization observed on fresh blast cells.

VDR expression on ALL blast cells

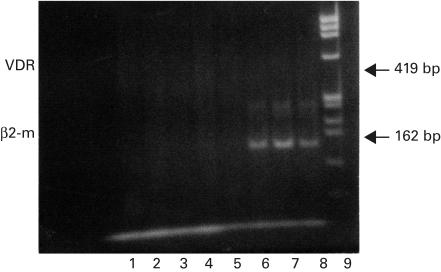

To clarify whether the VD effect on malignant lymphoid progenitors could be related to the expression of VDR, we performed RT-PCR analysis in four ALL patients by examining their frozen blast cells at diagnosis. RT-PC products and β2m mRNA were used to monitor the presence of the RNA in each sample and reported in Fig. 2, lanes 5–8.

Fig. 2.

Detection by RT-PCR of VDR in four cases of B cell precursors ALL: lanes 1–4. Blast cells were tested at diagnosis. RT-PCR products of β2mRNA are shown in lanes 5–8. Lane 9 shows molecular weight φX174/HAE III marker. The different genes studied and the size of the amplified fragments are labelled on the left and right sides of the panel, respectively.

Figure 2 shows that VDR mRNA are not detectable in all samples examined (four of four patients, lanes 1–4). One of the four patients, lane 5, was not available for the contemporary absence of both VDR and β2m (RNA).

Discussion

VD is not only the positive regulator of the calcium homeostasis, but also an immunomodulator. It has been reported that it inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation [19], as well as B cell differentiation and the antibody response [20]. The physiological role of VD on normal haematopoiesis is, however, not fully elucidated. These biological activities on the immune system are mediated by binding to nuclear receptor for 1,25-(OH)2-D3 [21], which belongs to the steroid receptor superfamily, and acts as a ligand-inducible transcription factor [22]. Its appearance on lymphocytes coincides with cell entry into G1 phase of the cell cycle, and the concentration of the receptor protein reaches a peak at G1 beta and declines during the S phase [19]. In our work, we show that VD inhibits clonogenic growth of in vitro normal activated lymphoid B and T cell progenitors.

VD is also a differentiation-inducing agent and an important modulator of cellular proliferation for a number of malignant cell types. The presence of its receptor has been shown in breast cancer [23], in human melanoma [24], neuroblastoma [25], prostate cancer [26] and myeloid leukaemia cells [27]. Concerning myeloid lineage, it has been reported previously that myeloid precursors at all stages of differentiation are equipped with the machinery required to trigger the VD-dependent genetic programme, leading eventually to terminal differentiation. In other words, they contain VDR protein that is fully active in binding their sites and in promoting transcription [13]. Recently it has been shown that VD induces differentiation of a retinoid acid-resistant acute promyelocytic leukaemia cell line (UF-1) [28] and that VD-responsive genes are induced by all-trans-retinoic acid treatment of M2-type leukaemic blast cells [27].

Conversely, the activity of VD on the growth and differentiation of acute lymphoid leukaemia cells have scarcely been investigated. Therefore, we turned our attention to the effects of this hormone on B lineage malignant progenitor cells. We have demonstrated that VD inhibited in vitro the growth of B lineage leukaemic cells without inducing a cytotoxic effect. Additionally, in preliminary experiments we observed that VD did not induce differentiation either in semisolid or liquid culture (two B lineage ALL tested; data not shown). VDR expression investigated in frozen B lineage blast cells at diagnosis and before treatment was not detected in all samples tested. As its expression in distinct leukaemic cell lines is regulated differentially upon the effect of proliferation or differentiation inducers [29,30], further investigation should be performed after the beginning of the culture. In addition, as in most antigen expression, the VD receptor is influenced by the cells' relationship with the bone marrow microenvironment [31], and its expression in malignant cryopreserved lymphoblastic cells may not become evident before a brief period of culture.

Furthermore, our results suggest that distinct factors may regulate such an interplay (e.g. VD binding proteins, alterations of cellular oncogenes regulating cellular proliferation and differentiation, effect of VD on growth factors modulating haemopoietic precursors). In particular, these interactions between VD and growth factors have been demonstrated previously in other cell systems. The capacity of the hormone to modulate the expression of a macrophage-derived cytokine (granlulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) [32] and to inhibit IL12 production by activated macrophages and dendritic cells by acting at the transcriptional level has been reported [33]. The involvement of TGF-beta 1 in the mechanism of action of VD on some leukaemic cell lines has been demonstrated recently: it is an autocrine mediator of human myelomonocytic U937 leukaemia cell growth arrest and differentiation induced by VD and retinoids [34], and is involved in the antiproliferative effect of a VD analogue, EB1089, on HL60 cells [35]. In human prostate cancer cell lines the VDR content and transcriptional activity do not fully predict antiproliferative effects of VD, suggesting that growth inhibition by VD requires VDR, but is modulated by non-receptor factors that are cell-line-specific [26].

Our work, together with the above observations, leads us to suggest that the regulation of some critical growth and differentiation factor receptors could play a key physiological role of this hormone.

The possibility of enhancing the effects of VD in vitro by combining the hormone with other molecules such as growth factors or other chemotherapic agents has been explored. Recently the synergistic effect of VD with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on the differentiation of the human monocytic cell line U937 has been demonstrated [36] with interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor in inducing the monocytoid differentiation of human promyelocytic cells [37], and with IL4 in enhancing its antiproliferative effect on mouse monocytic leukaemia cells [38]. Another approach is to combine VD with other inducers of differentiation presenting a synergistic effect [39]. The interaction of VD with 5-Aza-2′deoxycytidine was shown to be synergistic with respect to the loss of clonogenicity of the HL-60 leukaemic cells [40]. The combined treatment of VD or its analogue novel 20-epi VD and 9-cis retinoic acid has been shown recently to produce a synergistic decrease of clonal proliferation, induction of differentiation and apoptosis of acute promyelocytic leukaemia cells [41].

The clinical use of 1,25-(OH)2-D3 for leukaemia is limited, due not only to its calcaemic side-effects but also because 1,25-(OH)2-D3 alone fails to eliminate the leukaemic clone [41]. More recently, new vitamin D derivatives have been generated with extraordinarily potent inhibitory effects on leukaemic cell growth in vitro [42], without producing hypercalcaemia [43] and inhibition of normal myeloid clonal proliferation [44]. Therefore the synergistic effect of the hormone and its analogues with either chemotherapeutic agents or growth factors must be explored further.

The possibility of using growth inhibitors or inducers of differentiation for the therapy of leukaemias or other tumours has recently received considerable interest. Concerning acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), therapy fails in approximately one-third of children and two-thirds of adult patients [45,46]. In childhood ALL, particularly, the immediate challenge is to develop new approaches for cases that have relapsed after intensive multi-agent chemotherapy [45].

In conclusion, our work suggests that the in vitro study of VD and its analogues in combination with other drugs or growth factors in acute leukaemias deserves further investigation. Furthermore, it contributes to understanding of the mechanism of action of this hormone in promoting cellular inhibition of clonal growth of malignant lymphoid B cell progenitors.

References

- 1.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisman JA. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor and role of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in human cancer cells. In: Kumar R, editor. Vitamin D. Boston: Martinus-Nijhoff Publishing; 1984. pp. 365–82. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grande A, Manfredini R, Pizzanelli M, et al. Presence of a functional vitamin D receptor does not correlate with vitamin D3 phenotypic effects in myeloid differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 1997;4:497–505. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. The morfological classification of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: concordance among observers and clinical correlation. Br J Haematol. 1981;47:553–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1981.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Does-Van der Berg A, Bartram C, Basso G, et al. Minimal requirements for diagnosis, classification and evaluation of he treatment of childood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in the ‘BFM’ Family Cooperative Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1992;20:497–505. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madsen M, Johnsen HE, Hansen PW, Christiansen SE. Isolation of human T and B lymphocytes by E rosette gradient centrifugation. Characterization of the isolated populations. J Immunol Meth. 1980;33:323–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgoulias V, Marion S, Consolini R, Jasmin C. Characterization of normal peripheral blood T and B cells colony forming cells: growth factors(s) and accessory cell requirements for their in vitro proliferation. Cell Immunol. 1985;90:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(85)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izaguirre CA, Curis J, Messner H, McCulloch EA. A colony assay for blast cell progenitors in non T non B (common) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1981;7:823–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Consolini R, Bréard J, Bourinbaiar S, et al. Abnormal in vitro differentiation of peripheral blood clonogenic B cells in common acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1986;67:796–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Consolini R, Legitimo A, Cattani M, et al. The effect of cytokines, including IL-4, IL-7, stem cell factor, insulin-like growth factor on childood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 1997;21:753–61. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(97)00048-9. 10.1016/s0145-2126(97)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consolini R, Scamardella F, Legitimo A, et al. Evaluation of minimal residual disease in high risk childood acute lymphoblastic leukemia using an immunological approach during complete remission. Haematologica. 1993;78:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Consolini R, Pui C-H, Behm FG, Raimondi S, Campana D. In vitro cytotoxicity of docetaxel in childhood acute leukemias. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:907–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legitimo A, Consolini R, Di Stefano R, Bencivelli W, Calleri A, Mosca F. Evaluation of the immunomodulatory mechanisms of photochemotherapy in transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)01985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald RJ, Swift GH, Przybyla AE, Chirgwin JM. Isolation of RNA using guanidinium salts. Meth Enzymol. 1987;152:219–27. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grande A, Manfredini R, Tagliafico E, et al. All-trans retinoic acid induces simultaneously granulocytic differentiation and expression of inflammatory cytokines in HL60 cells. Exp Hematol. 1995;23:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker AR, McDonnel DP, Hughes M, et al. Cloning and expression of full-length cDNA encoding human vitamin D receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3294–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miiyamoto K, Kesterson RA, Yamamoto H, et al. Structural organization of the human vitamin D receptor chromosal gene and its promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1165–79. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.8.9951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suggs SV, Wallace RB, Hirose T, Kawzshima EH, Itakura K. Use of synthetic oliginucleotides as hybridization probes: isolation of cloned cDNA sequences for human B2-microglobulin. Biotechnology. 1992;24:140–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigby WF, Noelle RJ, Krause K, Fanger MW. The effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human T lymphocyte activation and proliferation: a cell cycle analysis. J Immunol. 1985;135:2279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen WC, Vayuvegula B, Gupta S. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated inhibition of human B cell differentiation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;69:639–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veldman CM, De Cantorna MT, Luca HF. Expression of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D receptor in the immune system. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;374:334–8. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1605. 10.1006/abbi.1999.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato S. The function of vitamin D receptor in vitamin D action. J Biochem. 2000;27:717–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisman JA, Martin TJ, MacIntyre I, Moseley JM. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D receptor in breast cancer cells. Lancet. 1979;2:1335–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92816-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans SR, Houghton AM, Schumaker L, et al. Vitamin D receptor and growth inhibition by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in human malignant melanoma cell lines. J Surg Res. 1996;1:127–33. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Celli A, Treves C, Stio M. Vitamin D receptor in SH–SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells and effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on cellular proliferation. Neurochem Int. 1999;34:117–24. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(98)00075-8. 10.1016/s0197-0186(98)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhuang SH, Schwartz GG, Cameron D, Burnstein KL. Vitamin D receptor content and trascriptional activity do not fully predict antiproliferative effects of vitamin D in human prostate cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;126:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manfredini R, Trevisan F, Grande A, et al. Induction of a functional vitamin D receptor in all-trans-retinoic acid-induced monocytic differentiation of M2-type leukemic blast cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3803–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muto A, Kizaki M, Yamato K, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D induces differentiation of a retinoid acid-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line (UF-1) associated with expression of p21 (WAF1/CIP1) p27 (KIP1) Blood. 1999;93:2225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folgueira MA, Federico MH, Katayama ML, Silva MR, Brentani MM. Expression of vitamin D receptor (VDR) in HL-60 is differentially regulated during the process of differentiation induced by phorbol ester, retinoic acid or interferon-gamma. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;664:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folgueira MA, Federico MH, Roela RA, Maistro S, Katayama ML, Brentani MM. Differential regulation of vitamin D receptor expression in distinct leukemic cell lines upon phorbol ester-induced growth arrest. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:559–68. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito M, Kumagai M, Okazaki T, et al. Stromal cell-mediated transcriptional regulation of the CD13/aminopeptidase N gene in leukemic cells. Leukemia. 1995;9:659–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobler A, Miller C, Norman AW, Koeffler HP. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates the expression of a lymphokine (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) posttrascriptionally. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1819–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI113525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Ambrosio D, Cippitelli M, Cocciolo MG, et al. Panina–Bordignon P inhibition of IL-12 production by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Involvment of NF-kappaB downregulation in transcriptional repression of p40 gene. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:252–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Defacque H, Piquemal D, Basset A, Marti J, Commes T. Tranforming growth factor-beta1 is an autocrine mediator of U937 cell growth arrest and differentiation induced by vitamin D and retinoids. J Cell Physiol. 1999;178:109–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199901)178:1<109::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-X. 10.1002/(sici)1097-4652(199901)178:1<109::aid-jcp14>3.3.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung CW, Kim ES, Scol JG, et al. Antiproliferative effect of a vitamin D analog, EB1089, on HL-60 cells by the induction of TGF-beta receptor. Leuk Res. 1999;23:1105–12. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(99)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuckerman SH, Suprenant YM, Tang J. Sinergistic effectof granulocyte-macrophage colony-stiulating factor and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D on the differentiation of the human monocytic cell line U937. Blood. 1988;71:619–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberg JB, Larrik JW. Receptor-mediated monocytoid differentiation of human promyelocytic cells by tumor necrosis factor: synergistic actions with interferon-γ and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 1987;70:994–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasukabe T, Okabe-Kado J, Honma Y, Hozumi M. Interleukin-4 inhibits the differentiation of mouse myeloid leukemia M1 cells induced by dexamethasone, d-factor/leukemia inhibitory factor and interleukin-6, but not by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:181–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81278-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.James SY, Williams MA, Newland AC, Colston K. Leukemia cell differentiation: cellular and molecular interactions of retinoid and vitamin D. Gene Pharmacol. 1999;2:143–54. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Momparler RL, Dorè BT, Labibertè J, Momparler LF. Interaction of 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine with amsacrine or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, on HL-60 myeloid leukemic cells and inhibitors of cytidine deaminase. Leukemia. 1992;7:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elstner E, Linker-Israeli M, Le J, et al. Synergistic decrease of clonal proliferation, induction of differentiation, and apoptosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells after combined treatment with novel 20-epi vitamin D3 analogs and 9-cis retinoic acid. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:349–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI119164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pakkala S, Devos S, Elstner B, et al. Vitamin D3 analogs: effects on leukemic clonal growth differentiation and on serum calcium levels. Leuk Res. 1995;19:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(94)00065-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou J-Y, Norman AW, Akashi M, et al. Development of a novel 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 analog with potent ability to induce HL-60 cell differentiation without modulating calcium metabolism. Blood. 1991;78:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asou H, Koike M, Elstner E, et al. 19-nor vitamin D analogs: a new class of potent inhibitors of proliferation and inducers of differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cell lines. Blood. 1998;92:2441–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rivera GK, Raimondi SC, Hancock ML, et al. Improved outcome in childood acute lymphoblastic leukemia with reiforced early treatment and rotational combination chemotherapy. Lancet. 1991;337:61–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90733-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoelzer D. High-dose chemotherapy in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 1991;28:84–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]