Abstract

Tissue damage during cold storage and reperfusion remains a major obstacle to wider use of transplantation. Vascular endothelial cells and complement activation are thought to be involved in the inflammatory reactions following reperfusion, so endothelial targeting of complement inhibitors is of great interest. Using an in vitro model of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) cold storage and an animal model of ex vivo liver reperfusion after cold ischaemia, we assessed the effect of C1-INH on cell functions and liver damage. We found that in vitro C1-INH bound to HUVEC in a manner depending on the duration of cold storage. Cell-bound C1-INH was functionally active since retained the ability to inhibit exogenous C1s. To assess the ability of cell-bound C1-INH to prevent complement activation during organ reperfusion, we added C1-INH to the preservation solution in an animal model of extracorporeal liver reperfusion. Ex vivo liver reperfusion after 8 h of cold ischaemia resulted in plasma C3 activation and reduction of total serum haemolytic activity, and at tissue level deposition of C3 associated with variable level of inflammatory cell infiltration and tissue damage. These findings were reduced when livers were stored in preservation solution containing C1-INH. Immunohistochemical analysis of C1-INH-treated livers showed immunoreactivity localized on the sinusoidal pole of the liver trabeculae, linked to sinusoidal endothelium, so it is likely that the protective effect was due to C1-INH retained by the livers. These results suggest that adding C1-INH to the preservation solution may be useful to reduce complement activation and tissue injury during the reperfusion of an ischaemic liver.

Keywords: complement, C1-inhibitor, inflammation, reperfusion, endothelium

INTRODUCTION

Organ transplantation is an established therapy for patients with end-stage organ disease [1]. However, the limited availability of donor organs and the territorial distribution of transplant units commonly make it necessary to preserve organs for several hours. During the last decade preservation methods have markedly improved, and grafts can now be used up to 12 h after removal from the donors [2–11]. Although cold storage of organs prolongs the period during which anoxic cells retain essential metabolic functions, there is evidence that hypothermia per se can induce tissue damage [12–16]. Therefore transplanted organs suffer from insult due to cold ischaemia and subsequent reperfusion. The duration of cold ischaemia correlates with delayed graft function, and seems to predispose transplanted organs to acute and chronic rejection [17,18].

The mechanisms of cold ischaemia and reperfusion injury are complex, involving both cellular and humoral immunity [19–22]. Experimental studies have shown that reperfusion after cold storage results in activation of the complement system (C) [23–30] through a pathway that may be antibody-dependent [31]. Local C activation [32] leads to generation of chemotactic factors C3a and C5a, to deposition of C4 and C3, and of the membrane attack complex. Deposition of the membrane attack complex even at a sublytic concentration may trigger tissue damage since it interferes with the anticoagulant and fibrinolytic capacity of vascular endothelial cells [33] and induces the expression of adhesion molecules [34]. Thus, C anaphylatoxins and injured endothelium may be involved in the recruitment of neutrophils that characteristically infiltrate reperfused tissues. Although it is not yet accepted as a clinical strategy, growing evidence suggests that inhibition of C activation at the time of reperfusion may improve the function and survival of the transplant.

Inflammatory reactions due to C activation can be prevented by inhibiting C activation products, increasing cell expression or plasma concentration of physiological inhibitors. Targeting C inhibitor to the site of utilization significantly improves the protective effect by increasing local bioavailability, and avoids having to inhibit C systemically [35]. C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) is a serine-proteinase inhibitor with a broad spectrum of activity, inhibiting activated C1s and C1r, in addition to factor XIIa, kallikrein, and factor XIa of the coagulation contact system [36]. In the last decade C1-INH has been thoroughly studied as an in vivo C inhibitor, and there is evidence that it can be successfully used in several diseases besides replacement therapy in patients with hereditary or acquired angioedema [37,38]. Early inhibition of classical pathway activation with C1-INH reduced ischaemia/reperfusion injury [39–43], and reduced C-mediated cytoxicity in vitro and in ex vivo models of xenotransplantation [44–50].

The present study, using human endothelial cells and an animal model of ex vivo liver reperfusion, was undertaken to investigate the utility of adding C1-INH to the storage solution in preventing C activation and tissue injury due to reperfusion after cold ischaemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultured human umbilical endothelial cells

Human umbilical cords (15–20 cm long) from normal delivery of healthy volunteer mothers were emptied of blood and stored in sterile bags at 4°C. The cannulated umbilical vein was perfused with Ca2+ and Mg2+ free-HBBS (Gibco-BRL, UK) and with a solution of 0·1% collagenase containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, and the cords were incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The released cells were washed in sterile tubes and centrifuged at 180 × g for 10 min, then resuspended in Medium 199 (Gibco-BRL, UK) containing 20% FBS (Gibco-BRL, UK), and transferred to a 5-ml flask (about 2–4 × 104/cm2). Successful cultures reached confluence in 7–10 days. After primary culture, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) can only be maintained for further passage in the presence of endothelial growth factor (50 μg/ml) and heparin (100 μg/ml) (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO). Cells were confirmed as endothelial on the basis of their typical cobblestone morphology and positive staining for Von Willebrand factor (DAKO A/S, Denmark).

Passage of cells

Cells were passaged using trypsin (0·05%) and EDTA (0·02%), and seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates coated with 0·5% gelatin (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) at 2–3 × 104 cells per well. The cells were confluent in about 12 h. All the experiments were performed at the second or third passage.

Cell viability measurements

HUVEC metabolic activity was assessed by the capacity to convert tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) to insoluble purple formazan, as previously described [51]. The cleavage and conversion of MTT require active mitochondrial dehydrogenases of living cells, so the amount of colour formed is proportional to the number of viable cells. Cell survival was evaluated by measuring lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) activity using a commercial ‘Cytotoxicity Detection Kit’ (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). At the times indicated, wells were washed and cells were lysed with 200 μl of Triton X-100 (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO). The supernatants were removed, spun at 2000 × g for 3 min, and LDH released from the cells was measured.

C1-INH binding to HUVEC during cold storage

A C1-INH specific cell-surface ELISA was developed. HUVEC were grown to confluence on 0·5% gelatinized 96-well plastic plates, washed several times with PBS and incubated in University of Wisconsin preservation solution (UW) [10] or UW containing different amounts (30–120 μg/ml) of C1-INH (Immuno-Baxter, Vienna) at 4°C for 0 or 24, 48 and 72 h. At the end of the storage, to detect C1-INH on the cell surface HUVEC were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (50 μl) for 30 min and washed again with PBS. The cells were then incubated at 4°C for 1 h with polyclonal rabbit antihuman C1-INH (1/5000 dilution) (DAKO A/S, Denmark) followed by incubation with peroxidase conjugated goat anti rabbit IgG (1/5000 dilution) (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO). HUVEC incubated with normal rabbit IgG (1/1000 dilution) (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) and peroxidase conjugated goat anti rabbit IgG served as control. After the cells were washed three times with PBS, the plates were developed with 50 μl of o-phenylenediamine-dihydrochloride (Sigma) and read at 492 nm.

For immunovisualization of C1-INH bound to HUVEC, the cells were grown to confluence on 0·5%-gelatinized cover slips and treated as above reported. Alternatively HUVEC were treated with highly purified C1-INH [52] that had been peroxidase conjugated with a commercial kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The cells were stained with diaminobenzidine tetrachloride, washed with H2O and dried with ethanol. The slides were then viewed by light microscopy at ×200 and ×400 magnification. Photographs were taken with Kodak Ektachrom film, ASA 400.

In additional experiments HUVEC were treated with peroxidase conjugated C1-INH (120 μg/ml) for 4 h at 4°C at the end of cold storage in presence of UW solution only.

Inhibition of C1s activity

HUVEC were grown on gelatin-coated 96-well microtiter plates and treated with UW or UW plus C1-INH for 48 h at 4°C. At the end of incubation the supernatants were discharged, and HUVEC were washed three times with 200 μl of PBS for 10 min in gentle agitation. With this washing procedure there was no C1-INH activity detectable in fluid phase (supernatants). The activity of C1-INH, both in supernatants and cell-bound, was measured by its ability to neutralize the amidolytic activity of exogenous C1s (Immunochrom C1-Inh, Immuno-Baxter).

Donor animals and reperfusion experiments

The Ethical Committee of the University of Milan approved the research protocol. Pigs weighing from 20 to 25 kg served as organ donors and recipients. General anaesthesia with sodium-pentotal and mechanical ventilation with isofluorane and oxygen was provided to all animals. The livers were removed from donors with a standard technique, perfused through the portal vein and hepatic artery with 250–300 ml of UW solution (group 1) or with UW plus C1-INH (20 IU/ml) (group 2) and stored at 4°C for 8 h. All livers were flushed through the portal vein and hepatic artery with 300 ml of saline and reperfused for 2 h in an extracorporeal circuit connected to a living pig according to the Abouna model [53]. Hepatic perfusion was carried out at 37°C through the hepatic artery and portal vein at physiological pressure and blood flow rate for 2 h.

Histology

Biopsies were taken from the donor livers before and at the end of cold storage, and after 30 min and 2 h of ex vivo reperfusion. For each biopsy, one tissue specimen was fixed for 12–24 h in buffered 4% formaldehyde for light microscopy; the second was embedded in OCT gel (Tissue-tek Miles Scientific, Naperville IL) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

For light microscopy, each biopsy was included in paraffin blocks; consecutive 4-micron sections were stained with haematoxilin-eosin, Masson thrichrome and PAS with and without diastase digestion. Under light microscopy, sections were blindly scored for tissue injury as follow: 0, no increase of the inflammatory infiltration; 1, mild portal and/or lobular inflammatory infiltration; 2, moderate portal and/or lobular inflammatory infiltration with occasional microabscesses; 3, diffuse portal and/or lobular inflammatory infiltration with microabscess formation and/or focal spotty hepatocyte necrosis/apoptosis; 4, diffuse portal and/or lobular inflammatory infiltration with microabscesses, multifocal/diffuse hepatocyte necrosis or apoptosis and microhaemorrhagies of the Disse space.

For immunohistochemical in situ detection of C1-INH and C3, sections were obtained from frozen specimens, adherent to poly l-lysin-coated slides, dewaxed and rehydrated. Slides were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antihuman C1-INH (1 : 1000) (Dako A/S, Denmark) or sheep polyclonal antipig C3 (1 : 500) (The Binding Site, UK) for 1 h at room temperature, washed and further incubated with En Vision System (Dako) for 30 min. The immunohistochemical reaction was developed with diaminobenzidine tetrachloride.

Complement measurements

Plasma (EDTA 10 mm) and serum samples were obtained from the afferent and efferent lines of the extracorporeal circuit 5, 30 and 120 min after liver reperfusion. C activation was evaluated by measuring total haemolytic activity (The Binding Site, UK) and the degree of C3 activation. C3 activation was assessed on immunostained blotting membranes after SDS-PAGE. This method simultaneously evaluates the native protein and its activation fragments. Briefly, plasma samples were loaded onto a SDS-8% polyacrylamide gel and separated under nonreducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene-difluoride membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA) by electroblotting, blocked for 2 h at 4°C with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline-0·1% Tween-20, washed and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with polyclonal sheep antipig C3 (1 : 2000) (The Binding Site, UK). The C3 bands were visualized with biotin conjugated donkey anti sheep IgG (Sigma) and an avidin-alkaline phosphatase substrate (Sigma). The blotting membranes were analysed with a high-performance scanner and Image Master software (Pharmacia, Upsala, S) to establish the level of protein activation, the cleaved protein being expressed as a percentage of total protein (band II versus bands I plus II). The interassay variation of this method is 10% and the lower limit of detection of cleaved C3 is 5–7% of total C3.

Clinical chemistry

Serum samples were obtained from the afferent and efferent lines of the extracorporeal circuit 5, 30 and 120 min after liver reperfusion. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity was measured by a standard assay in use at hospital laboratory.

Statistics

Results are reported as mean ± s.d.. For statistical comparisons, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used.

RESULTS

In vitro binding of C1-INH to HUVEC

Greater than 2–3 times more rabbit anti C1-INH bound to monolayers of HUVEC than did the control rabbit IgG, confirming the previous data [54] that HUVEC can express C1-INH. When HUVEC were cold stored in presence of C1-INH there was an increase in the binding of polyclonal anti C1-INH. The binding was maximum after 48 h at 4°C in presence of 120 μg/ml C1-INH (Fig. 1, upper panel). C1-INH bound to HUVEC was also readily detected by immunohistochemistry using peroxidase-conjugated C1-INH. The inhibitor appeared to be present on HUVEC in a diffuse pattern (Fig. 1, lower panel). Similar results were obtained when, after 48 h of cold storage in UW solution, HUVEC were treated with C1-INH for 4 h at 4°C.

Fig. 1.

Binding of C1-INH to endothelial cells in vitro. (a) shows that the binding of C1-INH (120 μg/ml) was maximum after 48 h of cold storage. (Shown are means ± s.d. of three experiments in triplicate.) (b) the immunostaining for C1-INH in HUVEC treated with UW preservation solution or peroxidase conjugated C1-INH. HUVEC receiving C1-INH showed a diffuse pattern of staining. (Sections were counterstained with eosin.)

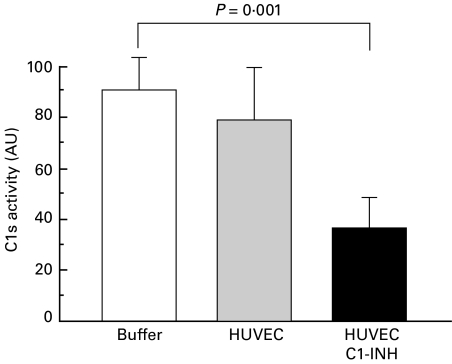

Inhibitory activity by cell-bound C1-INH

Figure 2 shows clearly that C1-INH on the HUVEC surface had the ability to inhibit amidolytic activity of exogenous C1s, whereas HUVEC per se did not.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of C1s activity by C1-INH bound to HUVEC. Shown are the changes in amidolytic activity of exogenous C1s induced by HUVEC or HUVEC treated with C1-INH (120 μg/ml). Means ± s.d. of three experiments run in triplicate for each group. AU = arbitrary unit.

HUVEC viability

Cell viability was evaluated by measuring LDH release and MTT conversion before and after cold storage. After 48–72 h at 4°C, LDH and MTT levels were 85–95% of the basal values without significant difference between cells stored in presence of UW or UW plus C1-INH (120 μg/ml).

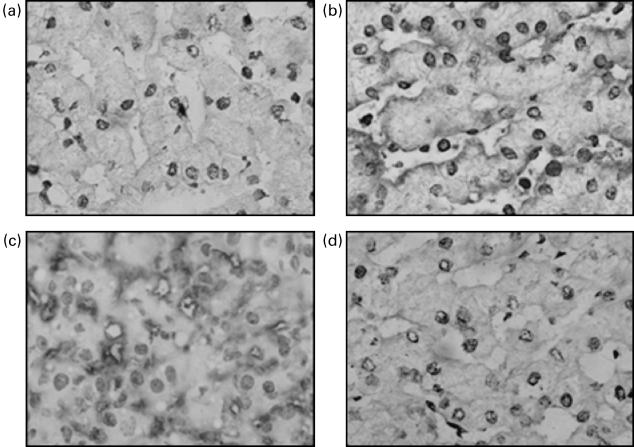

Immunohistochemical localization of C1-INH after liver cold storage

The finding that in vitro C1-INH can bind to endothelial cells was confirmed by immunohistochemistry on liver tissue. Sections of livers cold stored in presence of C1-INH demonstrated a definite immunoreactivity localized on the sinusoidal pole of the liver trabeculae, linked to sinusoidal endothelium (Fig. 3a, b). This was not seen in sections of livers stored in presence of UW alone.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical detection of C1-INH and C3 in liver tissue.Before reperfusion, sections of UW-treated livers showed no staining using rabbit anti-C1-INH (a), whereas definite immunoreactivity was evident at the sinusoidal pole of livers treated with UW plus C1-INH (b). After 2 h of reperfusion, C3 deposition was present at the sinusoidal borders of the trabeculae in UW-treated livers (c), while it was not detected in C1 INH-treated livers (d). (× 1000).

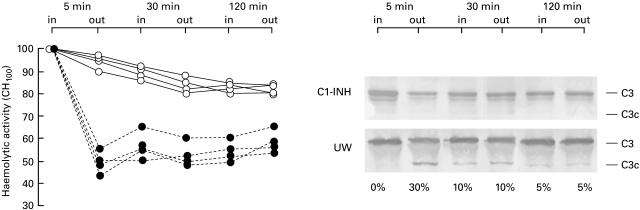

Inflammatory reactions during reperfusion of pig liver

We found that C1-INH can bind to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells during hypothermia, so we investigated whether cell-bound C1-INH could reduce C activation and tissue inflammatory reactions at the time of liver reperfusion. Immediately after the beginning of reperfusion of untreated livers, there was clear evidence of C activation, as indicated by the decrease in total complement activity (CH100) and generation of C3 activation products in plasma from the efferent line (Fig. 4). C activation at tissue level was assessed by immunohistochemical analysis of C3 fixation in the livers. In biopsies taken before storage or within 30 min from reperfusion there was no or scanty C3 deposition, whereas marked C3 sinusoidal immunoreactivity was observed in liver specimens obtained after 2 h of reperfusion (Fig. 3c). C activation was not seen in plasma and tissue from livers cold stored with C1-INH (Fig. 3d). However, we can not exclude that some activation occurred below the sensibility of our detection methods.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of complement activation during liver reperfusion by cell-bound C1-INH. At specific time points CH100 and C3 activation were measured in samples from the portal vein (in) and hepatic vein (out) of pig livers cold stored in the presence of UW (U25CF) or of UW plus C1-INH (○). The percentage of cleaved C3 is reported at the bottom of each lane of the immunoblotting membrane.

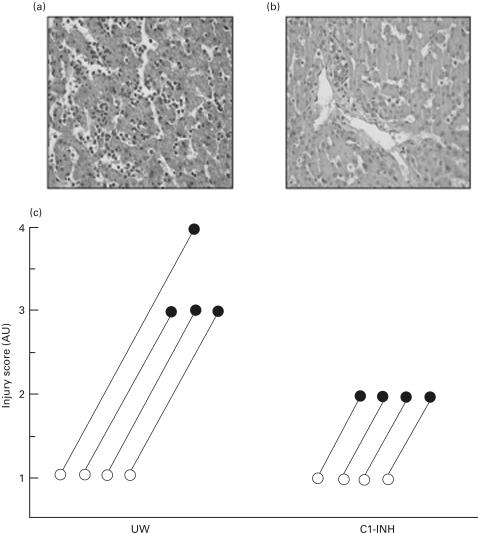

Morphological analysis of porcine liver tissues showed the typical picture of ischaemia/preservation injury. In all cases, basal biopsies showed no or scanty inflammatory cells, predominantly polymorphonucleated type, in the portal spaces or sinusoids, without evidence of hepatocyte damage. Neutrophil infiltration progressively increases in biopsies taken after 30 min and 2 h of reperfusion, both in C1-INH treated and untreated animals. However, in untreated livers inflammation was much more evident, with microabscesses formation and spotty necrosis in centrilobular areas (Fig. 5a), while in C1-INH treated animals only a mild increase in portal and lobular inflammatory infiltration was generally observed (Fig. 5b), with no or minimal cell injury. Injury scores in basal and after 2 h reperfusion biopsies are reported in Fig. 5c, for untreated (UW) and treated (UW + C1-INH) animals, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Histological pictures after 2 h reperfusion of an untreated pig liver showing diffuse necro-inflammatory activity (a) compared with C1INH-treated liver featuring only mild increase in sinusoidal neutrophils (b). (Haematoxilin-eosin, 400 ×.) (c) The injury scores in basal and after 2 h reperfusion biopsies, in the group of untreated (UW) and C1INH-treated animals (UW + C1INH). Reperfusion injury was scored from 0 to 4 as reported in Material and Methods. AU = arbitrary unit.

Clinical chemistry

Compared with basal values, during liver reperfusion there was a slight increase in AST and ALT plasma levels without difference between livers treated with UW or UW plus C1-INH.

DISCUSSION

The increasing use of transplantation as the therapy of choice for end stage organ failure has brought to the fore the problem of how best to preserve the ischaemic organ. It is widely believed that pathological events during reperfusion are at least in part an amplification of the cell damage induced by cold storage. Low temperature itself interferes with cell homeostatic processes, and endothelial cells are especially vulnerable to the effect of cold.

This study demonstrates that C1-INH can bind to endothelial cells and that cell-bound C1-INH can reduce effectively C activation, and probably also tissue inflammatory reactions during liver reperfusion.

Incubation of HUVEC with C1-INH after cold storage, resulted in the binding of the inhibitor to the cell surface (Fig. 1). The level of binding increased during cold storage, indicating that C1-INH binds to some ligand that is newly expressed by cold-activated cells. C1-INH inhibits its target proteinase by a suicide substrate mechanism that leads to the formation of inactive complex with the enzyme [36]. Cell-bound C1-INH was functionally active since retained the ability to inactivate exogenous C1s (Fig. 3); thus the majority of the inhibitor is unlikely to be bound to C1s expressed on the cell surface [55].

Previous studies [56–59] have shown that at the tissue level C1-INH can bind to several ligands, including heparin, and various components of the extracellular matrix, e.g. collagen IV, laminin, entactin and fibrin, but to our knowledge, there is no information on any endothelial ligand induced by hypothermia. We can speculate that C1-INH might interact with heparin or heparin-like molecules expressed by cold-activated endothelial cells [60]. In this case heparin would also potentiate C1-INH activity [61]. Whatever the ligand, the binding to endothelial cells results in a high local concentration that might enhance the anti-inflammatory effects of C1-INH at the level of damaged endothelium.

To assess whether our in vitro findings could have any clinical relevance, we chose an animal model of ex vivo allo-reperfusion of isolated liver. Livers were stored up to 8 h in presence of UW solution or UW with C1-INH added (20 IU/ml). In preliminary experiments we had found that cold storage in UW solution for 8 h was the minimum time to induce clear signs of tissue inflammation and C activation, and that 20 IU/ml was the optimal concentration of C1-INH to show its protective effects and the binding to endothelium. In our ex vivo model of reperfusion, C activation can occur through the alternative pathway in the early phase of extra-corporeal circulation. We therefore compared the level of C activation in blood samples collected from portal vein and hepatic veins at the same time. Much of the C activation occurred during the passage of blood through the organs (Fig. 4) indicating that C would be activated locally. In the early steps of the inflammatory response, recruitment of PMN into reperfused tissue is associated with rapid endothelial expression of adhesion molecules, in part due to C activation. Thus, C1-INH bound to endothelial cells (Fig. 3) would reduce PMN infiltration by preventing or reducing C activation. The effectiveness of C1-INH in the storage solution is clearly demonstrated by the normal levels of C haemolytic activity and the absence of C3 activation products (Fig. 4) in plasma samples collected directly at site of blood efflux from the reperfused organs. To prevent the passage of C1-INH into extracorporeal circuit, all livers have been extensively flushed with saline through the portal vein and hepatic artery before reperfusion. Thus it is likely that in the C1-INH treated livers, the absence or the very low levels of C activation (Fig. 4) in plasma from the efferent line was due to cell-bound C1-INH (Fig. 3). Although the ligand remains to be identified, the findings that after cold storage there was an increased binding of C1-INH to endothelial cells seems to indicate that this reaction take place as a response to cell damage. Since cell-bound C1-INH retains the ability to inhibit C activation in perfused livers, this vascular–perivascular cross-linking of C1-INH could represent an important mechanism for in vivo control of local C activation and vascular permeability [62]. Concomitant with the inhibitory effect on C activation in plasma, cell-bound C1-INH markedly reduced sinusoidal tissue deposition of C3 [24], the portal and lobular inflammatory infiltration and microabscess formation compared to those observed in livers of untreated animals (Fig. 5). At variance with the study of Straatsburg et al. [32], we had no evidence of intrahepatocyte C3 deposition both in UW and UW plus C1-INH treated livers.

During reperfusion there was only a slight increase in ALT and AST plasma levels both in UW and C1-INH treated livers. Although the lowest levels were measured in plasma from C1-INH treated livers, the difference was not significant. The short reperfusion time in our model, associated with the effectiveness of UW solution per se was probably the reason of the absence of significant change in AST and ALT plasma levels.

Several C inhibitors are under investigation for their ability to attenuate tissue injury in many models of ischaemia and reperfusion [63–66]. Each one seems to be effective in reducing damage, but a growing body of evidences indicates that C1-INH represents a good candidate to attenuate reperfusion injury. Modulation of C activation by C1-INH appears to be an effective mean of preserving ischaemic tissues from reperfusion injury [41], attenuating graft failure after transplantation [40,67], and prolonging graft survival in xenotransplantation [48,49]. Recently it has been shown that targeting the sites of C activation with C inhibitors [50,66] has the advantage to increase the protective effects and to obviate the need to inhibit C systemically.

In conclusion, the ability of C1-INH to bind to endothelial cells during graft storage, its broad inhibitory activity, the stability and the half-life of the protein, together with the relatively low risk of disease transmission, favour its use for better protection of organs against storage and reperfusion injuries.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Al Davis Jr., Boston, for his critical comments, and Dr A. Mancini of Immuno-Baxter, Italy, for the supply of complement C1 inhibitor.

This work was supported by a grant from Ministero della Sanità (Progetto Finalizzato, IRCCS, 1998–00)

REFERENCES

- 1.Gridelli B, Remuzzi G. Strategies for making more organs available for transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:404–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belzer FO, Southard JH. Principles of solid-organ preservation by cold storage. Transplantation. 1988;45:673–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198804000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeschke H. Preservation injury: mechanisms, prevention and consequences. J Hepatol. 1996;25:774–80. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menasche P, Termignon JL, Pradier F, et al. Experimental evaluation of Celsior, a new heart preservation solution. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1994;8:207–13. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orak JK, Singh AK, Rajagopalan PR, Singh I. Morphological analysis of mitochondrial integrity in prolonged cold renal ischemia utilizing Euro-Collins versus University of Wisconsin preservation solution in a whole organ model. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:122–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemasters JJ, Thurman RG. Reperfusion injury after liver preservation for transplantation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:327–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingemansson R, Bolys R, Budrikis A, Lindgren A, Sjoberg T, Steen S. Addition of calcium to Euro-Collins solution is essential for 24-hour preservation of the vasculature. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:408–13. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)00897-1. 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)00897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minor T, Vollmar B, Menger MD, Isselhard W. Cold preservation of the small intestine with the new Celsior-solution. First experimental results. Transpl Int. 1998;11:32–7. doi: 10.1007/s001470050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moutabarrik A, Mourid M, Nakanishi I. The effect of organ preservation solutions on kidney tubular and endothelial cells. Transpl Int. 1998;11:58–62. doi: 10.1007/s001470050103. 10.1007/s001470050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kevelaitis E, Nyborg NC, Menasche P. Protective effect of reduced glutathione on endothelial function of coronary arteries subjected to prolonged cold storage. Transplantation. 1997;64:660–3. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199708270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clavien PA, Harvey PR, Strasberg SM. Preservation and reperfusion injuries in liver allografts. An overview and synthesis of current studies. Transplantation. 1992;53:957–78. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen TN, Dawson PE, Brockbank KG. Effects of hypothermia upon endothelial cells: mechanisms and clinical importance. Cryobiology. 1994;31:101–6. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1994.1013. 10.1006/cryo.1994.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook NS, Zerwes HG, Rudin M, Beckmann N, Schuurman HJ. Chronic graft loss: dealing with the vascular alterations in solid organ transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2413–8. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00703-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullen S, Haworth SG, Warren JD. Donor organ preservation fluids differ in their effect on endothelial cell function. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1991;10:999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carles J, Fawaz R, Hamoudi NE, Neaud V, Balabaud C, Bioulac-Sage P. Preservation of human liver grafts in UW solution. Ultrastructural evidence for endothelial and Kupffer cell activation during cold ischemia and after ischemia-reperfusion. Liver. 1994;14:50–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1994.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidalgo MA, Sarathchandra P, Fryer PR, Fuller BJ, Green CJ. Effects of hypothermic storage on the vascular endothelium: a scanning electron microscope study of morphological change in human vein. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1995;36:525–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halloran PF, Aprile MA, Farewell V, et al. Early function as the principal correlate of graft survival. A multivariate analysis of 200 cadaveric renal transplants treated with a protocol incorporating antilymphocyte globulin and cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1988;46:223–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagano H, Tilney NL. Chronic allograft failure: the clinical problem. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313:305–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toledo-Pereyra LH, Suzuki S. Neutrophils cytokines, and adhesion molecules in hepatic ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:758–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Moine O, Louis H, Demols A, et al. Cold liver ischemia-reperfusion injury critically depends on liver T cells and is improved by donor pretreatment with interleukin 10 in mice. Hepatology. 2000;31:1266–74. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.7881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiagarajan RR, Winn RK, Harlan JM. The role of leukocyte and endothelial adhesion molecules in ischemia- reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linke R, Wagner F, Terajima H, Thiery J, Teupser D, Leiderer R, Hammer C. Prevention of initial perfusion failure during xenogeneic ex vivo liver perfusion by selectin inhibition. Transplantation. 1998;66:1265–72. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199811270-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chenoweth DE, Cooper SW, Hugli TE, Stewart RW, Blackstone EH, Kirklin JW. Complement activation during cardiopulmonary bypass: evidence for generation of C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:497–503. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102263040901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scoazec JY, Borghi-Scoazec G, Durand F, et al. Complement activation after ischemia-reperfusion in human liver allografts: incidence and pathophysiological relevance. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:908–18. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scoazec JY, Delautier D, Moreau A, et al. Expression of complement-regulatory proteins in normal and UW-preserved human liver. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:505–16. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill JH, Ward PA. The phlogistic role of C3 leukotactic fragments in myocardial infarcts of rats. J Exp Med. 1971;133:885–900. doi: 10.1084/jem.133.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaeschke H, Farhood A, Bautista AP, Spolarics Z, Spitzer JJ. Complement activates Kupffer cells and neutrophils during reperfusion after hepatic ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:G801–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.4.G801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinckard RN, O'Rourke RA, Crawford MH, et al. Complement localization and mediation of ischemic injury in baboon myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:1050–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI109933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin BB, Smith A, Liauw S, Isenman D, Romaschin AD, Walker PM. Complement activation and white cell sequestration in postischemic skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H525–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collard CD, Vakeva A, Bukusoglu C, Zund G, Sperati CJ, Colgan SP, Stahl GL. Reoxygenation of hypoxic human umbilical vein endothelial cells activates the classic complement pathway. Circulation. 1997;96:326–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiser MR, Williams JP, Moore FD, Jr, Kobzik L, Ma M, Hechtman HB, Carroll MC. Reperfusion injury of ischemic skeletal muscle is mediated by natural antibody and complement. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2343–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straatsburg IH, Boermeester MA, Wolbink GJ, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, Frederiks WM, Hack CE. Complement activation induced by ischemia-reperfusion in humans: a study in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy. J Hepatol. 2000;32:783–91. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80247-0. 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christiansen VJ, Sims PJ, Hamilton KK. Complement C5b-9 increases plasminogen binding and activation on human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:164–71. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tedesco F, Pausa M, Nardon E, Introna M, Mantovani A, Dobrina A. The cytolytically inactive terminal complement complex activates endothelial cells to express adhesion molecules and tissue factor procoagulant activity. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1619–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahu A, Lambris JD. Complement inhibitors: a resurgent concept in anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Immunopharmacology. 2000;49:133–48. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)80299-4. 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis AE 3rd. C1 inhibitor and hereditary angioneurotic edema. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:595–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.003115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caliezi C, Wuillemin WA, Zeerleder S, Redondo M, Eisele B, Hack CE. C1-Esterase inhibitor: an anti-inflammatory agent and its potential use in the treatment of diseases other than hereditary angioedema. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:91–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirschfink M, Nurnberger W. C1 inhibitor in anti-inflammatory therapy: from animal experiment to clinical application. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:225–32. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00048-6. 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heimann A, Takeshima T, Horstick G, Kempski O. C1-esterase inhibitor reduces infarct volume after cortical vein occlusion. Brain Res. 1999;838:210–3. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01740-0. 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehmann TG, Heger M, Munch S, Kirschfink M, Klar E. In vivo microscopy reveals that complement inhibition by C1-esterase inhibitor reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury in the liver. Transpl Int. 2000;13:S547–50. doi: 10.1007/s001470050399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buerke M, Murohara T, Lefer AM. Cardioprotective effects of a C1 esterase inhibitor in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1995;91:393–402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buerke M, Prufer D, Dahm M, Oelert H, Meyer J, Darius H. Blocking of classical complement pathway inhibits endothelial adhesion molecule expression and preserves ischemic myocardium from reperfusion injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:429–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horstick G, Heimann A, Gotze O, et al. Intracoronary application of C1 esterase inhibitor improves cardiac function and reduces myocardial necrosis in an experimental model of ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1997;95:701–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.3.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dalmasso AP. The complement system in xenotransplantation. Immunopharmacology. 1992;24:149–60. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(92)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalmasso AP, Platt JL. Prevention of complement-mediated activation of xenogeneic endothelial cells in an in vitro model of xenograft hyperacute rejection by C1 inhibitor. Transplantation. 1993;56:1171–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199311000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalmasso AP, Platt JL. Potentiation of C1 inhibitor plus heparin in prevention of complement-mediated activation of endothelial cells in a model of xenograft hyperacute rejection. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:1246–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Stefano R, Frosini F, Scavuzzo M, et al. C1-Inh and heparan sulfate can prevent discordant rejection. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:1172–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heckl-Ostreicher B, Wosnik A, Kirschfink M. Protection of porcine endothelial cells from complement-mediated cytotoxicity by the human complement regulators CD59, C1 inhibitor, and soluble complement receptor type 1. Analysis in a pig-to-human in vitro model relevant to hyperacute xenograft rejection. Transplantation. 1996;62:1693–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199612150-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fiane AE, Videm V, Johansen HT, Mellbye OJ, Nielsen EW, Mollnes TE. C1-inhibitor attenuates hyperacute rejection and inhibits complement, leukocyte and platelet activation in an ex vivo pig-to-human perfusion model. Immunopharmacology. 1999;42:231–43. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00008-9. 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsunami K, Miyagawa S, Yamada M, Yoshitatsu M, Shirakura R. A surface-bound form of human C1 esterase inhibitor improves xenograft rejection. Transplantation. 2000;69:749–55. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Denizot F, Lang R. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. Modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J Immunol Meth. 1986;89:271–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pilatte Y, Hammer CH, Frank MM, Fries LF. A new simplified procedure for C1 inhibitor purification. A novel use for jacalin-agarose. J Immunol Meth. 1989;120:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abouna GM, Ganguly PK, Hamdy HM, Jabur SS, Tweed WA, Costa G. Extracorporeal liver perfusion system for successful hepatic support pending liver regeneration or liver transplantation: a pre-clinical controlled trial. Transplantation. 1999;67:1576–83. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199906270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmaier AH, Murray SC, Heda GD, Farber A, Kuo A, McCrae K, Cines DB. Synthesis and expression of C1 inhibitor by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drouet C, Reboul A. Biosynthesis of C1r and C1s subcomponents. Behring Inst Mitt. 1989;84:80–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perlmutter DH, Glover GI, Rivetna M, Schasteen CS, Fallon RJ. Identification of a serpin-enzyme complex receptor on human hepatoma cells and human monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3753–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sahu A, Pangburn MK. Identification of multiple sites of interaction between heparin and the complement system. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:679–84. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90079-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patston PA, Schapira M. Regulation of C1-inhibitor function by binding to type IV collagen and heparin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230:597–601. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.6010. 10.1006/bbrc.1996.6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hauert J, Patston PA, Schapira M. C1 inhibitor cross-linking by tissue transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14558–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marcum JA, Rosenberg RD. Heparinlike molecules with anticoagulant activity are synthesized by cultured endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;126:365–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caldwell EE, Andreasen AM, Blietz MA, et al. Heparin binding and augmentation of C1 inhibitor activity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;361:215–22. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0996. 10.1006/abbi.1998.0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nurnberger W, Heying R, Burdach S, Gobel U. C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate for capillary leakage syndrome following bone marrow transplantation. Ann Hematol. 1997;75:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s002770050321. 10.1007/s002770050321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Narayana SVBY, Volanakis JE. Therapeutic intervention in the complement system. New Jersey: The Humana Press; 2000. Inhibition of Complement Serine Proteases as a Therapeutic Strategy. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kroshus TJ, Salerno CT, Yeh CG, Higgins PJ, Bolman RM 3rd, Dalmasso AP. A recombinant soluble chimeric complement inhibitor composed of human CD46 and CD55 reduces acute cardiac tissue injury in models of pig-to-human heart transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69:2282–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill J, Lindsay TF, Ortiz F, Yeh CG, Hechtman HB, Moore FD., Jr Soluble complement receptor type 1 ameliorates the local and remote organ injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion in the rat. J Immunol. 1992;149:1723–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mulligan MS, Warner RL, Rittershaus CW, et al. Endothelial targeting and enhanced antiinflammatory effects of complement inhibitors possessing sialyl Lewisx moieties. J Immunol. 1999;162:4952–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Struber M, Hagl C, Hirt SW, Cremer J, Harringer W, Haverich A. C1-esterase inhibitor in graft failure after lung transplantation. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1315–8. doi: 10.1007/s001340051065. 10.1007/s001340051065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]