Abstract

The cytokine osteopontin (Eta-1) leads to macrophage-dependent polyclonal B-cell activation and is induced early in autoimmune prone mice with the lpr mutation, suggesting a significant pathogenic role for this molecule. Indeed, C57BL/6-Faslpr/lpr mice crossed with osteopontin−/– mice display delayed onset of polyclonal B-cell activation, as judged by serum immunoglobulin levels. In contrast, they are subject to normal onset, but late exacerbation of lymphoproliferation and evidence of kidney disease. These observations define two stages of Faslpr/lpr disease with respect to osteopontin-dependent pathogenesis that should be taken into account in the design of therapeutic approaches to the clinical disease.

Keywords: Lymphoproliferation, immunoglobulin, osteopontin, knockout mase

INTRODUCTION

The lpr mutation of the fas gene, caused by insertion of an early transposable element and consecutively aberrant transcription, prevents apoptosis of autoreactive T cells and leads to a form of autoimmune disease that resembles systemic lupus erythematosus. An early pathological indicator is the induction of various cytokines. Among the first cytokines detectable to be induced is Eta-1/osteopontin, which may be secreted by double negative T cells. Dysregulation of osteopontin expression begins at the onset of autoimmune disease and continues throughout the course of this disorder. Total levels of osteopontin RNA in the peripheral lymph nodes of MRL/lpr but not MRL/n mice increase by approximately 4 orders of magnitude, in contrast to IL-2, IL-3, IL-4 or IFN-γ [1], suggesting a potentially prominent role for osteopontin in the pathophysiology of lpr disease.

In vitro analysis of osteopontin has shown that it induces polyclonal B-cell activation through up-regulation of IL-12 and preferentially enhances the IgG2a and IgG2b but not IgG1 response [2]. A second mechanism that may be responsible for early effects of osteopontin on Faslpr/lpr disease comes from the finding that B-cell-specific expression of an osteopontin transgene results in B-cell expansion and secretion of immunoglobulins [3]. These two observations open the possibility that elevated osteopontin expression early in the disease process may contribute to elevated levels of serum immunoglobulin characteristic of the early phase of disease.

A second class of effects of osteopontin that may serve to inhibit disease progression comes from its ability to inhibit type 2 responses, in part through ligation of CD44 that reduces expression of IL-10 and IL-4 [4,5]. In principle, this interaction may normally serve to ameliorate the elaboration of Th2 cytokines that drives the later part of this disorder and associated kidney disease. Here we test this hypothesis using gene-targeted mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 Faslpr/lpr mice (Taconic) were crossed for two generations with C57BL/6 × 129[k.o.]OPN G1 mice (generously provided by Drs Susan R. Rittling and David Denhardt, Rutgers University, New Jersey, USA) to yield the following groups: Fas+/+OPN+/+, Fas+/+OPN−/–, Faslpr/lprOPN+/+ and Faslpr/lprOPN−/–. Littermates were housed together in a 12-h light/dark cycle with chow and water ad libitum until the age of either 170–180 days or 200–220 days. In contrast to MRL mice, the C57Bl/6 and 129 strains are not prone to autoimmune disease. Their use allows the selective analysis of the manifestations mediated by the lpr mutation. Their immunogenetic similarity makes skewing of the results by incomplete back-crossing unlikely [6–9]. For each data point, unless indicated otherwise, 3–5 mice were analysed and the results are presented as mean value ± standard error.

Extraction of immune organs

Inguinal, axillar, submandibular and mesenteric lymph nodes were extracted and single cell suspensions were obtained by grinding with sieve and pestle. Spleen and thymus were excised and single cell suspensions were generated from them by grinding between frosted glass slides. From all three organs, red cells were removed by hypotonic lysis using ACK buffer for 5 min.

Flow cytometry

Surface markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, B220) were analysed by fluorescence activated cell sorter following four-colour two-step staining (FITC, PE, APC, biotin–streptavidin–AMCA, antibodies from PharMingen, streptavidin–AMCA from Coulter). 1 × 106 cells were incubated on ice with 1 µg of the relevant antibody for 20 min followed by two washes with 200 µl PBS, then streptavidin–AMCA was added for additional 20 min on ice and two washes with 200 µl PBS. The cells were resuspended in 2% PFA in PBS for analysis within 48 h.

Anti-single-stranded DNA antibodies

ELISA plates were coated with protamine for 1 h at room temperature. The wells were washed and coated with heated salmon sperm DNA overnight followed by blocking with 1% BSA in PBS. Serum was added in a dilution series and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The wells were washed and probed with biotinylated anti-IgG for 1·5 h at room temperature. Streptavidin horseradish peroxidase was added and catalysed colour development from pnpp substrate was determined in an ELISA reader. The data were plotted double reciprocally and the half-maximal point was calculated from the regression line.

Anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies

Biotinylated double-stranded DNA was incubated at 2 µg/ml with various concentrations of serum in BSA blocked flexiplates at 37°C for 2 h. Simultaneously, ELISA plates were coated with avidin D before blocking with BSA. The serum/biotinylated DNA mixture was transferred to the ELISA plate wells and incubated for 1·5 h at room temperature. The wells were washed and probed with biotinylated anti-IgG for 1·5 h at room temperature. Streptavidin horseradish peroxidase was added and catalysed colour development from pnpp substrate was determined in an ELISA reader. The data were plotted double reciprocally and the half-maximal point was calculated from the regression line.

Immunoglobulin isotypes

Blood samples were drawn and allowed to clot for 2 h at room temperature. Serum was obtained by centrifugation and stored frozen until use. Isotypes of serum antibodies were screened in duplicates and in two separate experiments using a commercial kit (Pharmingen). The results were calculated as percentage difference from standards included in the kit after adjustment for background absorbance. The numbers were then converted to relative units with the mean values for Fas+/+OPN+/+ mice around day 175 equal to 1 (the percentages of standard for Fas+/+OPN+/+ mice were: IgG1 18·1%, IgG2a 38·1%, IgG2b 50·3%, IgG3 25·5%, IgM 21·7% and IgA 41·4%). The data are presented as mean ± standard error.

Histology

For analysis of autoimmune nephritis or encephalitis, kidneys and brains were preserved in 10% buffered formalin and haematoxilin/eosin-stained sections were prepared for microscopic evaluation.

Statistics

Differences among datasets were analysed for statistical significance according to the Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon U-tests.

RESULTS

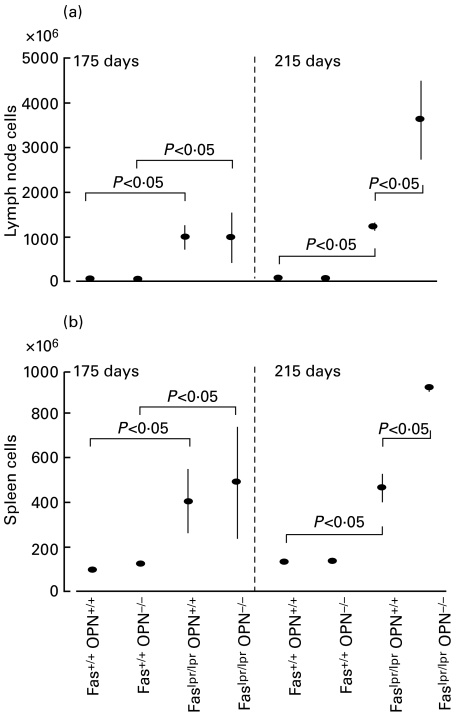

The absence of osteopontin causes late augmented proliferation of spleen and lymph nodes. Progression of lymphoproliferation as judged by cell numbers of lymph nodes and spleens was assessed on days 175 and 215. At 175 days, the total number of lymph node cells in Faslpr/lpr mice was around 1 × 109 for both OPN+/+ and OPN−/– genotypes (compared to 2–3 × 107 for Fas+/+ mice). Similarly, splenomegaly was manifest at 3·5–4·5 × 108 cells in both OPN+/+ and OPN−/– genotypes (compared to 1 × 108 cells in Fas+/+ mice). In contrast, by day 215 the lymph node cell numbers for Faslpr/lprOPN+/+ mice remained around 1–2 × 109 while they increased to 3·5 × 109 in Faslpr/lprOPN−/– mice and the spleen cell numbers of Faslpr/lprOPN+/+ mice remained around 4 × 108 while they increased to more than 8 × 108 in Faslpr/lprOPN−/– mice. (Fig. 1a,b).

Fig. 1.

Disease progression in lymph nodes and spleen. (a,b) Proliferation was assessed in early (175 days) and late (215 days) disease by determination of cell numbers of combined inguinal, brachial, submandibular and mesenteric lymph nodes (a) or of whole spleens (b). Each data point represents mean ± standard error from three to six mice. (c) The composition of subpopulations of cells in lymph nodes was determined by flow cytometry. Various hatches represent the percentages of total for the indicated cell types (CD4 stands for CD3+CD4+CD8−, CD8 is short for CD3+CD4−CD8+).

Lymphoproliferation in lpr disease is caused largely by expansion of CD3+CD4−CD8− T cells. Such cells constitute less than 5% of regular lymph nodes but increase to some 40–60% in the Faslpr/lpr genotype. The lymph node composition of B cells, conventional T cells (CD3+CD4+CD8− or CD3+CD4−CD8+) or double-negative T cells was unaffected by the absence of osteopontin gene products (Fig. 1c).

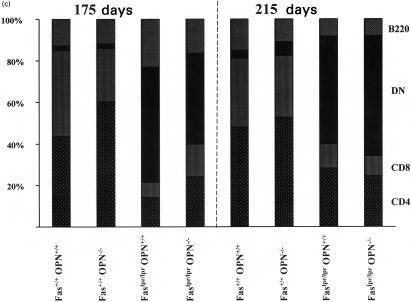

Osteopontin knockout delays polyclonal B-cell activation. Osteopontin has been shown to induce polyclonal B-cell activation and isotype switching in vitro [2] and in osteopontin transgenic mice [3]. Overproduction of this cytokine may contribute to the excessive polyclonal B-cell activation that characterizes lpr-disease. On C57Bl/6 background, Faslpr/lpr mice have elevated immunoglobulins of the IgG and IgM classes [8]. Mice with homozygous lpr mutation and wild-type osteopontin displayed substantial elevations of IgG, IgM and IgA at 175 days and maintained increased levels to day 215. In Faslpr/lpr mice with deleted osteopontin gene the elevation of serum immunoglobulins was largely absent on day 175. Unexpectedly, on day 215 induction of all immunoglobulin isotypes reached or exceeded the elevations seen in Faslpr/lpr OPN+/+ mice (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Immunoglobulin levels in serum. (a) Immunoglobulin isotypes in serum were measured with a commercially available kit (PharMingen) and results are plotted as -fold induction with Fas+/+OPN+/+ equal to 1. (b) Antibody of the IgG class to single-stranded DNA and double-stranded DNA (not shown) were determined by ELISA. Each data point represents mean value ± standard error. Statistical significance was analysed with the non-parametric U-test.

Autoimmunity is part of the lpr phenotype. One of its manifestations is the generation of anti-DNA antibodies. On day 175, no substantial levels of anti‐single stranded DNA IgG are induced in Faslpr/lpr mice. However, by day 215, Faslpr/lprOPN+/+ mice have generated anti-DNA antibodies and this is comparable to Faslpr/lpr mice with OPN−/– background. Consistent with earlier reports [8], antibodies to double-stranded DNA were elevated only modestly (data not shown) (Fig. 2B).

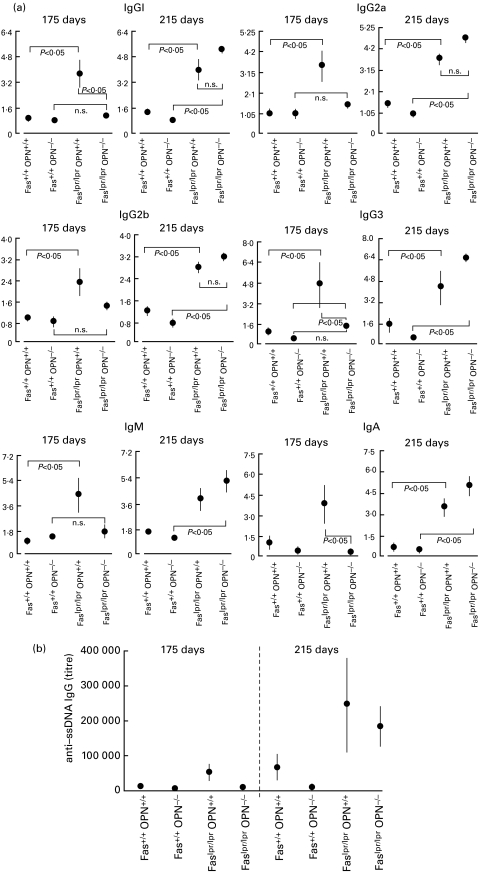

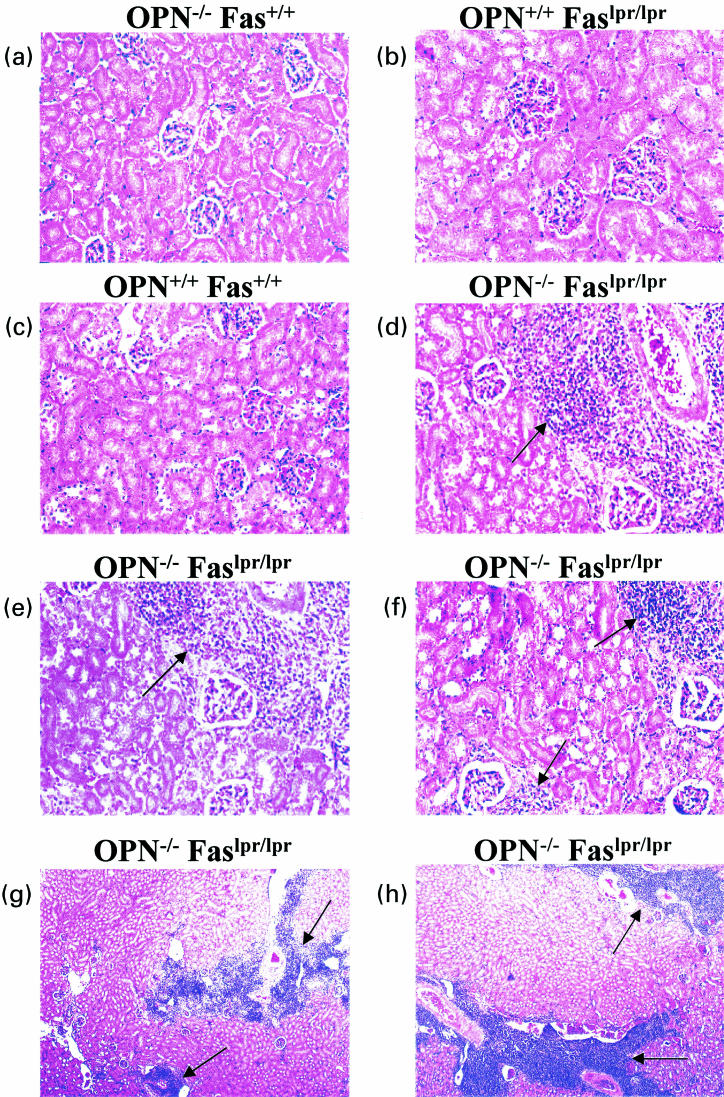

The absence of osteopontin gene products predisposes to autoimmune nephritis. Affection of the kidneys by the lpr mutation of the fas gene becomes manifest as immune complex glomerulonephritis and depends on the genetic background. It is most severe in MRL mice and mild in C57BL/6 mice. Consistently, we did not observe glomeruloneophritis in Faslpr/lprOPN+/+ mice. However Faslpr/lprOPN−/– mice had histological evidence of moderate nephritis, characterized mainly by lymphocytic infiltrates, which worsened from day 175 to day 215. This was not independent of the lpr mutation because kidney histology of Fas+/+OPN−/– mice was unremarkable at both time points. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

Autoimmune nephritis. At 215 days, kidneys were extracted from mice with the indicated genotypes and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Histology slides were prepared and stained with haematoxilin/eosin. (a–f) One microscopic field, representative for 3–5 mice, is shown for each genotype under study, with the exception of Faslpr/lprOPN−/–, for which three representative fields (from distinct mice) are shown to illustrate the lymphocytic infiltrates. (g,h) A lower magnification of the kidneys from two distinct Faslpr/lprOPN−/– mice indicates the wide distribution of the lymphocytic infiltrates.

Autoimmune encephalitis has been reported to occur in conjunction with the lpr-phenotype in mice [10,11]. Haematoxilin-eosin stains of mouse brains (one section per mouse) did not reveal signs of encephalitis in any of the groups of mice (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest progression of lpr-disease in two stages. Early in disease osteopontin mediates pathology, whereas during a late stage osteopontin limits further exacerbation. These studies highlight earlier findings that lpr disease was marked by excessive expression of osteopontin, beginning very early in the course of this condition [1]. Osteopontin provokes polyclonal B-cell activation in the early phase of lpr disease and Faslpr/lprOPN−/– mice fail to develop significant levels of polyclonal B-cell activation in the first 6 months. This may reflect the contribution by osteopontin to the generation of Th1 cells through an IL-12/γ-interferon pathway. The later phase of disease, characterized by a second burst of polyclonal B-cell activation and production of pathogenic autoantibodies, is thought to depend on production of Th2 cytokines including IL-10/IL-4. Faslpr/lprOPN−/– mice display enhanced serum immunoglobulin levels and exacerbated lymphocyte expansion. Osteopontin-dependent down-regulation of IL-10 and induction of Type 1 mediators may normally inhibit this phase of disease. A biphasic mode of disease progression has also been described for β2-microglobulin-deficient mice [12]. During an early phase, there is a substantial increase in serum immunoglobulin in β2-microglobulin-deficient and -expressing mice alike, driven presumably by CD4+ T cells. In later disease, MHC class I wild-type mice produce increasingly excessive levels of immunoglobulin and pathogenic autoantibodies. In contrast, mice deficient in β2-microglobulin revert to almost normal levels in a later disease stage with consecutively substantially moderated renal pathology. The early phase of the disease is thought to reflect mainly dysregulated type 1 cytokine expression [13], while the late phase may be associated with increased production of type 2 cytokines by CD8+ cells or NK1+ cells [12].

The results of the present study conform with recent insights into the immunoregulatory activity of osteopontin. Characterization of OPN−/– mice has placed this cytokine at the centre of events that regulate the development of Th1 versus Th2 immunity through reciprocal effects on IL-12 and IL-10 expression [4]. Thus, OPN−/– mice do not develop sarcoid-type granulomas unless provided with purified osteopontin, they do not develop significant antiviral (HSV-1) delayed type hypersensitivity despite unimpaired T-cell proliferative responses to HSV-1 and they are defective in their ability to clear listeria after systemic infection. These in vivo models indicated characteristic alterations in the cytokine profile. T cells in the draining lymph nodes of HSV-1-infected OPN−/– mice produced elevated levels of IL-10 and markedly reduced levels of the type 1 cytokine IL-12 in comparison with controls. Addition of osteopontin to resident peritoneal macrophages in vitro efficiently induced IL-12 secretion and actively suppressed the IL-10 response. Osteopontin induction of IL-12 reflects engagement of the αvβ3 integrin. Conversely, osteopontin dependent inhibition of IL-10 depends on engagement of the CD44 receptor.

Susceptibility to glomerulonephritis of mice with the lpr mutation of the fas gene depends on the genetic background and is minimal in C57Bl/6 mice. Thus, the lpr mutation needs endogenous factors to generate severe renal injury [8,9]. Autoimmune glomerulonephritis in Faslpr/lpr mice is mediated by immunoglobulins [14,15] and depends on CD4+ T cells. MHC class II-deficient mice, which lack CD4+ T cells, develop lymphadenopathy but not autoantibodies or autoimmune renal disease [16]. Similarly, Faslpr/lpr mice with targeted disruption of the gene encoding MCP-1, an essential chemokine for T-cell and macrophage recruitment, have diminished lymph node and kidney pathology despite elevated serum immunoglobulin levels and kidney Ig/C3 deposits. This highlights the requirement for MCP-1 dependent leucocyte recruitment to initiate autoimmune disease [17]. Osteopontin knockout mice, in contrast to wild-type controls, develop kidney pathology. This becomes manifest predominantly through infiltrating immune cells whereas the glomeruli are only modestly affected. The lymophocytic infiltrations may in part be secondary to excessive lymphoproliferation during late disease in those mice.

Effects on lymphadenopathy, polyclonal immunoglobulin induction and autoimmune glomerulonephritis may involve distinct mechanisms because these phenomena can occur independently of one another. This is due, in part, to the involvement of distinct T-cell subsets. The expanding population of double negative T cells is derived from the CD8+ lineage, whereas kidney disease is mediated by autoreactive CD4+ cells [16,18]. Mice treated with cyclosporin A have a marked decrease in lymphoproliferation, expansion of double negative T cells, arthritis and glomerulonephritis and show significantly prolonged survival. These beneficial effects occur despite a lack of reduction in antibodies reactive with DNA, circulating immune complexes, rheumatoid factor titres or immunoglobulin concentrations, indicating that the B-cell hyperactivity of MRL-lpr/lpr mice can proceed without the T‐cell proliferative disease [19]. Nevertheless, the delay in polyclonal immunoglobulin secretion by B cells and late exacerbation of T-cell expansion in the absence of osteopontin may represent a single molecular mechanism. Diminished IL-12 induction at an early stage may reduce polyclonal activation of B cells, while the unopposed Th2 profile late in the disease may exacerbate both lymphoproliferation and immunoglobulin secretion leading to the unusual occurrence of nephritis in this strain.

These findings, together with previous reports [20–22], provide additional evidence for a differential role of type 1 and type 2 immunity during the course of lpr disease and indicate that the dominant form of immunity in individual patients with lpr-like disorders must first be established to allow rational and effective therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health research grants CA76176 to GFW and A137833 to HC. The authors are grateful to Colette Gramm for expert technical assistance. Drs Susan R. Rittling and David T. Denhardt generously provided the OPN−/– mice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patarca R, Wei FY, Singh P, Morasso MI, Cantor H. Dysregulated expression of the T cell cytokine Eta-1 in CD4−8− lymphocytes during the development of murine autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1177–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lampe MA, Patarca R, Iregui MV, Cantor H. Polyclonal B cell activation by the Eta-1 cytokine and the development of systemic autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 1991;147:2902–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iizuka J, Katagiri Y, Tada N, et al. Introduction of an osteopontin gene confers the increase in B1 cell population and the production of anti-DNA autoantibodies. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1523–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashkar S, Weber GF, Panoutsakopoulou V, et al. Eta-1 (osteopontin): an early component of type-1 (cell-mediated) immunity. Science. 2000;287:860–4. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.860. 10.1126/science.287.5454.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber GF, Ashkar S, Glimcher MJ, Cantor H. Receptor–ligand interaction between CD44 and osteopontin (Eta-1) Science. 1996;271:509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manheimer A, Bona C. Age-dependent isotype variation during secondary immune response in MRL/lpr mice producing autoanti-gamma-globulin antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15:718–22. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stassin V, Coulie PG, Birshtein BK, Secher DS, Van Snick J. Determinants recognized by murine rheumatoid factors: molecular localization using a panel of mouse myeloma variant immunoglobulins. J Exp Med. 1983;158:1763–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.5.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izui S, Kelley VE, Masuda K, Yoshida H, Roths JB, Murphy ED. Induction of various autoantibodies by mutant gene lpr in several strains of mice. J Immunol. 1984;133:227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley VE, Roths JB. Interaction of mutant lpr gene with background strain influences renal disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1985;37:220–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(85)90153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Sullivan FX, Vogelweid CM, Besch-Williford CL, Walker SE. Differential effects of CD4+ T cell depletion on inflammatory central nervous system disease, arthritis and sialadenitis in MRL/lpr mice. J Autoimmun. 1995;8:163–75. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1995.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelweid CM, Johnson GC, Besch-Williford CL, Basler J, Walker SE. Inflammatory central nervous system disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice: comparative histologic and immunohistochemical findings. J Neuroimmunol. 1991;35:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(91)90164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christianson GJ, Blankenburg RL, Duffy TM, et al. β2-microglobulin dependence of the lupus–like autoimmune syndrome of MRL-lpr mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:4932–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagi K, Haneji N, Hamano H, Takahashi M, Higashiyama H, Hayashi Y. In vivo role of IL-10 and IL-12 during development of Sjögren's syndrome in MRL/lpr mice. Cell Immunol. 1996;168:243–50. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolaja GJ, Fast PE. Renal lesions in MRL mice. Vet Pathol. 1982;19:663–8. doi: 10.1177/030098588201900611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hewicker M, Kromschroder E, Trautwein G. Detection of circulating immune complexes in MRL mice with different forms of glomerulonephritis. Z Versuchstierkd. 1990;33:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jevnikar AM, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH. Prevention of nephritis in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient MRL-lpr mice. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1137–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tesch GH, Maifert S, Schwarting A, Rollins BJ, Kelley VR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-dependent leukocytic infiltrates are responsible for autoimmune disease in MRL-Fas (lpr) mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1813–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pestano GA, Zhou Y, Trimble LA, Daley J, Weber GF, Cantor H. Inactivation of misselected CD8 T cells by CD8 gene methylation and cell death. Science. 1999;284:1187–91. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1187. 10.1126/science.284.5417.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mountz JD, Smith HR, Wilder RL, Reeves JP, Steinberg AD. CS-A therapy in MRL-lpr/lpr mice: amelioration of immunopathology despite autoantibody production. J Immunol. 1987;138:157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu C, Sun K, Tsai C, et al. Expression of Th1/Th2 cytokine mRNA in peritoneal exudative polymorphonuclear neutrophils and their effects on mononuclear cell Th1/Th2 cytokine production in MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Immunology. 1998;95:480–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zavala F, Masson A, Hadaya K, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor treatment of lupus autoimmune disease in MRL-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:5125–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magilavy DB, Foys KM, Gajewski TF. Liver of MRL/lpr mice contain interleukin-4-producing lymphocytes and accessory cells that support the proliferation of Th2 helper T lymphocyte clones. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2359–65. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]