Abstract

The expression of melanocortin MC1 receptors on human peripheral lymphocyte subsets was analysed by flow cytometry using rabbit antibodies selective for the human MC1 receptor and a panel of monoclonal antibodies against lymphocyte differentiation markers. The MC1 receptor was found to be constitutively expressed on monocytes/macrophages, B-lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and a subset of cytotoxic T-cells. Interestingly T-helper cells appeared to be essentially devoid of MC1 receptors. The results were confirmed by RT-PCR which indicated strong expression of MC1 receptor mRNA in CD14+, CD19+ and CD56+ cells. However, only a faint RT-PCR signal was seen in CD3+ cells, in line with the immuno-staining results that indicated that only part of the CD3+ cells (i.e. some of the CD8+ cells) expressed the MC1 receptor. The MC1 receptors' constitutive expression on immune cells with antigen-presenting and cytotoxic functions implies important roles for the melanocortic system in the modulation of immune responses.

Keywords: MC1 receptor, constitutive expression, monocytes, B-lymphocytes, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, natural killer cells

Introduction

The neuroendocrine transmitter α-MSH exerts a large array of central and peripheral effects by virtue of its binding to five subtypes of melanocortin receptors, MC1-5. The MC receptors are G-protein coupled and all five of them couple in stimulatory fashion to adenylate cyclase. The MC receptors are monomeric proteins thought to be built of seven transmembrane α-helices. The human MC receptors have a length of between 297 and 360 amino acids, with the proteins' extracellular N-terminus ranging 23–74 amino acids. The MC receptors show about 40–60% over all sequence homology, but share no obvious sequence similarity in their N-terminal domains [1]. The MC1 receptor was originally demonstrated on melanocyte-derived melanoma cells [1,2] and on melanocytes [3], but there is now also evidence that it is expressed on monocytes/macrophages [4,5], neutrophils [6] and dermal microvascular endothelial cells [7]. The reported effects of α-MSH on the immune system are primarily anti-inflammatory and include the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α [8], inhibition of NF-κB activation [9], induction of IL-10 synthesis [4], down-regulation of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells [10] and inhibition of neutrophil migration [11]. α-MSH is also shown to inhibit hapten-induced delayed-type hypersensitivity [12] and to reduce adjuvant arthritis [13]. A role for endogenous α-MSH in the control of the immune system appears probable. Many cells of the body, including the cells of the immune system express the α-MSH precursor pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and are shown to release MSH peptides [1]. Moreover, during various conditions of inflammation such release of MSH peptides is seen to be enhanced [1]. Still, the expression of MC1 on the main subsets of human lymphocytes has not been examined.

In this report we demonstrate for the first time the presence of the MC1 receptor on lymphocyte subsets by use of immunofluorescence labelling with polyclonal antibodies selective for the MC1 receptor and flow cytometry. Moreover we confirm the immuno-labelling data by mRNA analysis using RT-PCR with specific primers for the MC1 receptor. Our results show that, besides being expressed on the monocytes/macrophages, the MC1 receptor is constitutively expressed on B-cells, NK-cells and a subset of cytotoxic T-cells.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The isotypes, specificities and sources of the monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against different phenotypic lymphocyte differentiation markers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specificities of mAbs used herein

| Surface marker | mAb/clone | Isotype | Main reactivity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45 | 2B11 and | IgG1 | Leucocytes | Dako |

| PD7/26 | ||||

| CD3 | T3–4B5 | IgG1 | T cells and subsets of thymocytes | Dako |

| CD4 | MT310 | IgG1 | MHC class II restricted T cells | Dako |

| CD8 | DK25 | IgG1 | MHC class I restricted T cells | Dako |

| CD14 | TUK4 | IgG2a | Monocytes/macrophages | Dako |

| CD19 | HD37 | IgG1 | B cells | Dako |

| CD56 | MY 31 | IgG1 | Isoform of NCAM, NK-cells | Becton-Dickinson, |

| Negative control | DAK-G01 | IgG1 | A. niger glucose oxidase | Dako |

| Negative control | DAK-G05 | IgG2a | A.niger glucose oxidase | Dako |

The polyclonal M1-Y and M2-Y antibodies against the human MC1 receptor were previously described [14]. They had been raised by immunization of rabbits with, respectively, two unique 15 and 11 amino acid long synthetic peptides corresponding to the N-terminal of the MC1 receptor. Their specificity had been verified using various tests, which included their ability to stain cells expressing the recombinant MC1 receptor, while not staining cells lacking the MC1 receptor [14–16].

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood samples were donated by 5 healthy adult individuals, diluted 1: 2 with Tris-buffered Hank's salt solution, pH 7·2 (TH) and subjected to Ficoll-isopaque (Lymphoprep, Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) gradient centrifugation. The interface containing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was collected, washed in TH, supplemented with 0·2% human serum albumin (HSA) and antibiotics, and used in the immunofluorescence labelling experiments. Subpopulations of PBMC, were separated by Dynabeads (see below) and used for total RNA extraction.

Two-colour immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometric analysis of isolated PBMC

One hundred thousand living cells per well were plated into U-shaped microtitre plates in TH containing 0·2% HSA and 0·02% NaN3 and incubated with an appropriate concentration of rabbit-anti human MC1 antibodies for 30 min on ice. After the incubation the cells were washed three times in the same medium, containing 0·2% HSA and 0·02% NaN3. During the first wash the cells were centrifuged through a layer of neat FCS. After washing, FITC-conjugated swine antirabbit antibodies (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) were applied for 30 min in the dark on ice followed by a further wash, as described above. A final 30 min incubation with a phycoerythrin-conjugated mAb for a lymphocyte differentiation antigen was then applied, followed by another washing step. Appropriately labelled isotype-matched irrelevant mAbs (Dako or Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA; Table 1) and normal rabbit serum were used as controls for the determination of unspecific fluorescence. Flowcytometric analyses were performed using a FACScan flow-cytometer (Beckton Dickinson). The fluorescence data were displayed as dot plots and quantified using Cell Quest software. Anti CD45 mAbs were used to verify the staining of the whole leucocyte population.

Separation of subpopulations of PBMC

Subpopulations of PBMC from individual donors were obtained by positive selection using magnetic separation with goat antimouse immunomagnetic beads (Dynal) labelled with mAbs specific for T-cells (anti-CD3), B cells (anti-CD19), monocytes/macrophages (anti-CD14) and NK cells (anti-CD56), as previously described [17] and used for preparation of total RNA. The cells bound to the immunomagnetic beads were subjected to five washes with 10–20 times the initial cell/bead volume of ice-cold PBS, allowing nonbound cells to be completely removed. A minimum of 1000–1500 cells/sample were counted using a light microscope in order to ascertain that only cells bound to beads were present in the selected population [17]. The cells attached to the beads were then lysed, and the lysate was used for extraction of total RNA.

Total RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cell lysates of positively selected subpopulations of PBMC (see above) by the acid guanidinum thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method [18]. Single strand cDNA copies were made from 1 μg of total RNA using random hexamers and murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (PE Biosystems Nordic, Stockholm, Sweden). The RT step was performed at 42°C for 15 min followed by denaturation at 99°C for 5 min. The cDNA was used as template for PCR with primer pairs specific for the human MC1 receptor (MC1 forward 5′-TGGTGAGCTTGGTGGAGAACGC-3′ and MC1 reverse 5′-TCTTGAAGATGCAGCCGCACG-3′). The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 µl containing 20 pmol of each primer, 400 µm dNTPs and 3 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, 20 mm Tris pH 8·8, and 1 U Taq polymerase (Fermentas AB, Vilnius, Lithuania) and 2 µl cDNA. The PCR program was as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 63°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min The primers used would amplify a 686-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the MC1 receptor sequence. Samples containing the pE-11D plasmid with the cloned human MC1 receptor DNA served as a positive control [2]. For β-actin primers and protocols were as described [17]. PCR products were analysed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained by ethidium bromide and visualized by UV illumination. Amplified products were sequenced using an ABI Prism 377 sequencer and ABI sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer).

Results

Expression of the MC1 receptor on peripheral blood mononuclear cells

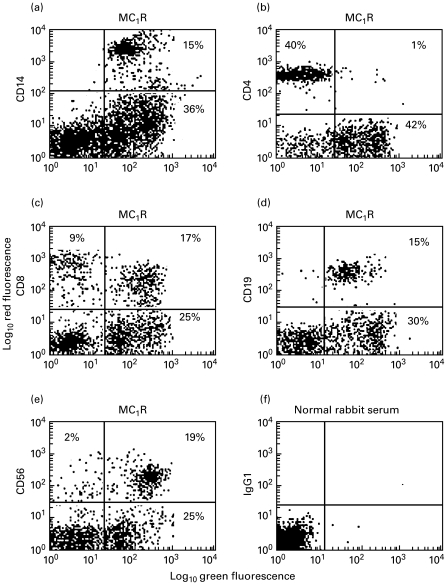

Peripheral blood lymphocytes were isolated from five donors and double-stained using monoclonal antibodies against lymphocyte differentiation markers and the polyclonal antibody M1-Y against the MC1 receptor. The results from 5 individual donors are summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 1. As can be seen practically all CD19 positive cells (B-lymphocytes) were stained by the MC1 receptor antibody. Also the majority of CD14 positive cells (monocytes) and CD56 positive NK cells were stained by the MC1 receptor antibody. Moreover, a subset of CD8+ cells expressed MC1 receptors. However, very few (i.e. virtually none) of the CD4+ cells stained for the MC1 receptor (Table 2 and Fig. 1b). Additional experiments, where the MC1 receptor M2-Y antibody was used, showed essentially the same pattern for the frequency of MC1R positive cells of the CD19, CD14, CD56, CD4 and CD8 positive leucocyte subsets (data not shown). Unspecific staining was excluded by using normal rabbit serum and isotype matched monoclonal antibodies (Table 1 and Fig. 1f). Thus, as can be seen from Fig. 1f an irrelevant IgG1 isotype-matched mAb did not bind to PBMC incubated with normal rabbit serum. Similar results as in Fig. 1f were obtained using an irrelevant IgG2a isotype-matched mAb and normal rabbit serum (data not shown).

Table 2.

Expression of the MC1 receptor (MC1R) on subpopulations of freshly isolated human PBMC. The table represents data from 5 different healthy adult donors using mAbs according to Table 1 for surface marker detection and the M1-Y antibody for MC1 receptor detection in conjunction with FACS analysis. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM

| Surface marker | Marker expression (% of total cell number) | Proportion of MC1R positive cells (% of marker positive cells) |

|---|---|---|

| CD14 | 10 ± 2 | 100 |

| CD19 | 12 ± 4 | 95 ± 5 |

| CD4 | 38 ± 6 | 4 ± 2 |

| CD8 | 30 ± 7 | 39 ± 15 |

| CD56 | 14 ± 2 | 86 ± 8 |

Fig. 1.

Dual colour flow cytometric analysis of MC1 receptor (MC1R) expression on subsets of isolated PBMC from a healthy adult donor. Anti-CD14 mAb was used to stain monocytes/macrophages (a), anti-CD4 mAb to stain TH cells (b), anti-CD8 mAb to stain CTLs (c), anti-CD19 mAb to stain B-cells (d) and anti-CD56 mAb to stain NK cells (e). Staining of MC1Rs was done using the M1-Y antiserum. An irrelevant IgG1 isotype mAb and normal rabbit serum served as one of the negative controls (f). (Similar results as in F were obtained using an irrelevant IgG2a isotype mAb and normal rabbit serum; data not shown).

Message for MC1 receptors is expressed in isolated subpopulations of PBMC

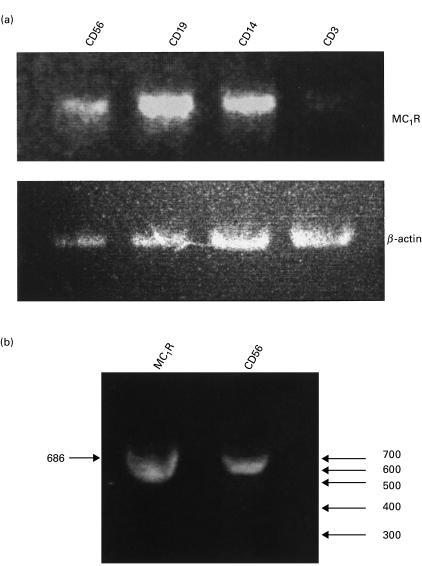

In order to investigate the expression of MC1 receptors in lymphocyte subsets RT-PCR was applied using specific primers for the human MC1 receptor on cDNA obtained from lymphocytes positively selected for CD3, C14, CD19 and CD56 by mAb-coupled immunomagnetic beads. As shown in Fig. 2 CD14, CD19 and CD56 selected cells invariably gave PCR products of the size corresponding to that of the MC1 receptor (686 bp). By contrast CD3+ cells gave only weak or faint signals (Fig. 2a). The lack of the MC1 mRNA signal in the latter cells were not due to differences in cDNA levels. This can be seen from Fig. 2a where the bands are compared with the band for β-actin PCR product (540 bp) of the identical samples. Figure 2b compares the MC1 receptor band of CD56 cells with the band obtained using a plasmid containing the human MC1 receptor. As seen both bands show similar mobility on the agarose gel. The identity of the presumed MC1 receptor DNA was verified by sequencing of the PCR product isolated from the CD56 cells. The sequence corresponding to nucleotides 138–523 of the PCR product could be read, and matched that of nucleotides 603–989 of the reported [2] MC1 receptor DNA sequence.

Fig. 2.

Detection of MC1 receptor transcripts in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by RT-PCR. Subpopulations of PBMCs were obtained by positive selection and used for preparation of cDNA followed by RT-PCR amplification and detection on agarose gels using ethidium bromide staining. (A) From left to right lanes represent RT-PCR bands using MC1R and β-actin selective primers for cells positively selected for CD56, CD19, CD14 and CD3. (B) RT-PCR bands obtained using an MC1R plasmid or cDNA from cells positively selected for CD56. Indicated by arrows to the right are the mobility of standard DNA, nt 300–700. Indicated by the arrow to the left is the 686 nt size of the band amplified from the MC1R plasmid.

Discussion

The present study gives unambiguous evidence for the expression of the MC1 receptor on subsets of peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy adult humans. The identity of the MC1 receptor is verified on several levels. Firstly, the same pattern for the distribution of the MC1 receptor on the lymphocyte subsets was seen using two different antibodies that had been raised by immunizing rabbit with two different peptides corresponding to 15 and 11 amino acid long epitopes in the N-terminus of the human MC1 receptor [14]. Simultaneous 2-colour immunofluorescense flow cytometry showed that all or almost all CD14+, CD19+ and CD56+ cells express MC1 receptors on their surface. By contrast no or only very few CD4+ cells were MC1 receptor positive, while approximately 1/3 of CD8+ cells stained for the MC1 receptor. Secondly, the expression of the MC1 receptor message was demonstrated in lymphocyte subsets with a distribution entirely compatible with the immunostaining. Thus, by use of RT-PCR a band with the correct size for an MC1 receptor message was demonstrated in CD14, CD19 and CD56 positive cells. By contrast CD3 positive cells (i.e. a T-cell population consisting of the CD4+ and CD8+ cells) showed only a faint signal corresponding to the MC1 receptor product, reflecting that only a part of the CD3+ population (CD8+ cells) expressed the message for the MC1 receptor. Thirdly, unambiguous verification for the MC1 receptor identity of the PCR amplified band was reached by the DNA sequencing.

According to the present results four important immune cell populations: monocytes/macrophages, B cells, CTLs and NK cells express MC1 receptors constitutively. Thus, MC1 receptors seem to be expressed in immune cells with antigen presenting and cytotoxic functions. Monocytes/macrophages participate both in the processing and presentation of the antigen to T-helper (TH) cells. After the activation with the aid of TH cells, macrophages mediate the delayed type hypersensitivity. B-cells are also important antigen presenting cells, besides their effector functions. CTLs and NK-cells are cytotoxic effector cells involved in the defence against viral infections and tumour cells.

The melanocortic peptides are known to affect immune and inflammatory responses, but their exact site(s) and mode of actions are still not very well defined. The melanocortic peptides act on the five subtypes of melanocortin receptors MC1-5. Melanocortic peptides are derived from a larger POMC precursor that may generate the shorter ACTH, α-, β- and γ-MSH peptides. All of these peptides are capable of activating the MC1 receptor, with the largest activity being shown by α-MSH. The MC2 receptor on the other hand is responsive only to ACTH (and fragments of ACTH down to ACTH(1–24)). The MC3-5 receptors are also responsive to the various MSH peptides with some variation in relative sensitivity compared to the MC1 receptor.

Earlier studies indicate that the melanocortins have a complex and multifaceted role in regulating the immune system. It is well established that POMC is expressed in cells of the immune system and is processed to ACTH in cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages [19]. Processing into α-MSH may also occur and has been demonstrated in a monocytic cell line [20]. Interestingly the α-MSH production in these cells was shown to be strongly up-regulated by stimulation with IL-6, TNF-α or concanavalin A [20]. Moreover, γ-MSH immunoreactivity was demonstrated in neutrophils of human eosinophilic patients [21].

The overall effect of melanocortic peptides appears to be anti-inflammatory, something that has been demonstrated in a number of animal models of inflammation where α-MSH was administered exogenously [1]. Exogenously applied α-MSH also inhibits the release of immuno-stimulatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α in whole blood, as well as in isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, after stimulation with bacterial lipopolysacharide [7,22]. These effects have earlier been attributed to the presence of MC1 receptors in monocytes/macrophages [1], a location for the MC1 receptor, which is also confirmed by the results of the present study. The fact that MC1 receptors are expressed not only on monocytes/macrophages, but also on the antigen presenting B-cells and on cells with cytotoxic functions (CTLs and NK-cells) strongly suggest that anti-inflammatory and immuno-modulatory effects of the melanocortic peptides are also mediated by actions on these cells. E.g. a previous study report that, depending on the concentrations used, ACTH and α-MSH could either augment or inhibit the IgE synthesis in an in vitro mononuclear cell system [23]. Our finding that only about one third of the CD8+ population express the MC1 receptors is also quite interesting. It thus appears that the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte subclass is heterogeneous with respect to MC1 receptor expression, something that might be taken as an indication for quite specific roles of the melanocortic system in propagating cytotoxic T-cell responses. The presence of the MC1 receptor on NK cells may also indicate a role of the melanocortic system for the regulation of MHC nonrestricted cell cytoxocicity.

It has been shown that the in vivo administration of α-MSH can induce hapten specific tolerance [12], thus further indicating very specific mode of actions of the POMC peptides in immune regulation. The essential complete absence of MC1 receptors on TH cells (results of present study) thus seems to disfavour a role of these cells in mediating the α-MSH effect in the delayed-hypersensitivity response and for the initiation of hapten specific tolerance, at least if these effects were to be propagated by the activation of MC1 receptors. A role for monocytes/macrophages is supported by the observation that hapten-specific α-MSH induced tolerance is dependent on IL-10 [12], a cytokine produced by the monocytes/macrophages. It is thus tempting to speculate that it is indeed the MC1 receptors on the monocytes/macrophages that are responsible for the development of the tolerance, rather than MC1 receptor lacking CD4+T cells. Studies directed towards how the melanocortins affect the interplay of TH cells and macrophages/monocytes might give insight into these questions.

There are some indications that other MC receptors besides the MC1 receptor might also have roles in the regulation of the immune system. Thus, expression of MC3 receptors has been demonstrated in murine macrophages [24]. There is also evidence for the expression of MC5 receptors on mouse B-lymphocytes [25]. Moreover, the expression of both MC1 and MC5 receptors were reported on a human mast cell line [26]. Finally, it should be mentioned that part of the α-MSH mediated effects may even be conveyed via a nonmelancortin receptor mediated pathway that mediate anti-inflammatory effects via the inhibition of NF-κB activation [1].

In summary our study provides evidence that MC1 receptors are expressed on subsets of lymphocytes, namely B-cells, NK cells and a subpopulation of cytotoxic T cells. By contrast the MC1 receptor was absent on T-helper cells. Moreover we confirm that MC1 receptors are present on monocytes/macrophages. The expression of MC1 receptors on antigen presenting cells, and cells with cytotoxic functions, lends support to specific roles for the melanocortic system in the regulation of the immune system.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Swedish MRC (04X-05957) and a grant from Melacure Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wikberg JES, Muceniece R, Mandrika I, Prusis J, Post C, Skottner A. New aspects on the melanocortins and their receptors. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42:393–420. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0725. 10.1006/phrs.2000.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chhajlani V, Wikberg JES. Molecular cloning and expression of the human melanocyte stimulating hormone receptor cDNA. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:417–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80820-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loir B, Perez Sanches C, Ghanem G, Lozano JA, Garcia-Borron JC, Jimenez-Cervantes C. Expression of the MC1 receptor gene in normal and malignant human melanocytes. A semiquantitative RT-PCR study. Cell Mol Biol. 1999;45:1083–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhardwaj R, Becher E, Mahnke K, Hartmeyer M, Schwarz T, Scholzen T, Luger TA. Evidence for the differential expression of the functional alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor MC-1 on human monocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:3378–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taherzadeh S, Sharma S, Chhajlani V, et al. α-MSH and its receptors in regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α production by human monocyte/macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1289–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catania A, Rajora A, Capsoni F, Minonzio F, Star RA, Lipton JM. The neuropeptide α-MSH has specific receptors on neutrophils and reduces chemotaxis in vitro. Peptides. 1996;17:675–9. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00037-x. 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmeyer M, Scholzen T, Becher E, Bhardwaj RS, Schwartz T, Luger TA. Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells express the melanocortin receptor type 1 and produce levels of IL-8 upon stimulation with alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone. J Immunol. 1997;159:1930–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catania A, Cutuli M, Garofalo L, Airaghi L, Valenza F, Lipton JM, Gattinoni L. Plasma concentrations and anti-l-cytokine effects of alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone in septic patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1403–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200005000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manna SK, Aggarwal BB. α-melanocyte stimulating hormone inhibits the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB activation induced by various inflammatory agents. J Immunol. 1998;161:2873–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalden DH, Scholzen T, Brzoska T, Luger TA. Mechanisms of the antiinflammatory effects of α-MSH. Role of transcription factor NF-κB and adhesion molecule expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;885:254–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elferink JG, de Koster BM. Inhibition of interleukin-8-activated human neutrophil chemotaxis by thapsigargin in a calcium- and cyclic AMP-dependent way. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:369–75. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00342-1. 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabbe S, Bhardwaj RS, Mahnke K, Simon MM, Schwarz T, Luger TA. α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone induces hapten-specific tolerance in mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipton JM, Ceriani G, Macalusco A, McCoy D, Carnes K, Biltz J, Catania A. Antiinflammatory effects of the neuropeptide α-MSH in acute, chronic, and systemic inflammation. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1994;741:137–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb39654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia Y, Skoog V, Muceniece R, Chhajlani V, Wikberg JES. Polyclonal antibodies against human melanocortin MC1 receptor. preliminary immunohistochemical localisation of melanocortin MC1 receptor to malignant melanoma cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;288:277–83. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia Y, Muceniece R, Wikberg JES. Immunological localisation of melanocortin 1 receptor on the cell surface of WM266-4 human melanoma cells. Cancer Letter. 1995;98:157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia Y, Wikberg JES, Chhajlani V. Expression of melanocortin 1 receptor in periaqueductal gray matter. Mol Neurosci. 1995;6:2193–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199511000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mincheva-Nilsson L, Kling M, Hammarström S, Nagaeva O, Sundquist K-G, Hammarström M-L, Baranov V. γδ T cells of human early pregnancy decidua: Evidence for local proliferation, phenotypic heterogeneity, and extrathymic differentiation. J Immunol. 1997;159:3266–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinum thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blalock JE. Proopiomelanocortin and the immune-neuroendocrine connection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;885:161–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajora N, Ceriani G, Catania A, Star RA, Murphy MT, Lipton JM. Alpha-MSH production, receptors, and influence on neopterin in a human monocyte/macrophage cell line. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:248–53. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson O, Virtanen M, Hilliges M, Hansson LO. Gamma-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-like immunoreactivity in blood cells of human eosinophilic patients. Acta Haematol. 1991;86:206–8. doi: 10.1159/000204836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catania A, Garofalo L, Cutuli M, Gringeri A, Santagostino E, Lipton JM. Melanocortin peptides inhibit production of proinflammatory cytokines in blood of HIV-infected patients. Peptides. 1998;19:1099–104. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00055-2. 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aebischer I, Stampfli MR, Zurcher A, et al. Neuropeptides are potent modulators of human in vitro immunoglobulin E synthesis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1908–13. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Getting SJ, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Agonism at melanocortin receptor type 3 on macrophages inhibits neutrophil influx. Inflamm Res. 1999;48(Suppl.):S140–1. doi: 10.1007/s000110050557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buggy JJ. Binding of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone to its G-protein-coupled receptor on B-lymphocytes activates the Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J. 1998;331:211–6. doi: 10.1042/bj3310211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artuc M, Grutzkau A, Luger T, Henz BM. Expression of MC1- and MC5-receptors on the human mast cell line HMC-1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;885:364–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]