Abstract

The specific role of lymphocyte apoptosis and transplant-associated atherosclerosis is not well understood. The aim of our study was to investigate the impact of T cell apoptotic pathways in patients with heart transplant vasculopathy. Amongst 40 patients with cardiac heart failure class IV who have undergone heart transplantation, 20 recipients with transplant-associated coronary artery disease (TACAD) and 20 with non-TACAD were investigated one year postoperative. Expression of CD95 and CD45RO, and annexin V binding were measured by FACS. Soluble CD95, sCD95 ligand (sCD95L), tumour necrosis factor receptor type 1 (sTNFR1), and histones were measured in the sera by ELISA. The percentage of cells expressing CD3 and CD4 was significantly reduced in TACAD as well as in non-TACAD patients as compared with control volunteers. Interestingly, the proportion of CD19+ (B cells) and CD56+ (NK) cells was increased in TACAD groups (versus non-TACAD; P < 0·01, and P < 0·001, respectively). In contrast to sCD95, the expression of CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and CD45RO (memory T cells), and sCD95L were significantly increased in non-TACAD and TACAD patients. T cell activation via CD95 with consecutive apoptosis was increased in both groups. The concentration of sTNFR1, IL-10 and histones was significantly elevated in sera from TACAD than non-TACAD patients, and in both groups than in healthy controls. These observations indicate that the allograft may induce a pronounced susceptibility of CD4+ T cells to undergo apoptosis and antibody-driven activation-induced cell death. This data may suggest a paradox immune response similar to that seen in patients with autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: TNFR1, transplant-associated coronary artery disease, apoptosis, CD95, CD95L, heart allograft

INTRODUCTION

Transplant vasculopathy limits the long-term success of heart transplantation (HTX), and is the leading cause of late mortality [1,2]. Transplant-associated coronary artery disease (TACAD) is a diffuse and progressive thickening of the arterial intima that develops in the major and minor coronary arteries of transplanted heart allograft [3]. The result is sudden and/or chronic progressive ischaemia damage to the transplanted heart with subsequent functional organ failure. Similar phenomena exist between ordinary atherosclerosis and transplant vasculopathy, which includes the massive presence of subendothelial inflammatory cells, intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation, and extracellular matrix reorganization [4]. Transplant vasculopathy is diffuse and frequently involves long segments of arteries. It is characterized by concentric intimal thickening, whereas ordinary atherosclerosis usually involves one part of the artery more heavily than other parts, the latter producing prominent eccentric lesions [4].

Numerous pathomechanisms have been thought to be involved in the development of TACAD, which includes immune-mediated vascular injury, inflammation of the vascular endothelium, ischaemia-reperfusion injury, cytomegalovirus infection, or metabolic risk factor [1]. Although the role of platelets in the development of atherosclerosis has been well recognized in TACAD [5], T cell-dependent mechanisms have been poorly studied in the TACAD population. Recently, a shift to Th2 cytokine profile, with consecutive B cell hyperreactivity has been indicated in HTX patients [6], and that T cell receptor expression can be triggered by chronic antigen stimulation [7].

We hypothesized that allograft is inducing high levels of epitope and soluble death-inducing receptors (DIR), and that T cells of patients with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)-verified TACAD may have heightened apoptotic turnover which contributes to the initiation and perpetuation of the thrombotic/ atherosclerotic process. T cells from patients after implantation of left-ventricular assist device, as well as from HTX recipients, had increased surface expression of CD95, and a higher rate of spontaneous apoptosis [8].

Following these observations we aimed to investigate cell populations from HTX recipients with TACAD and non-TACAD. To appropriately address this question, soluble DIR, annexin V binding to T cells, and the content of histones in the sera were measured. Furthermore, we investigated if T cells of the TACAD group are more likely to undergo activation-induced cell death (AICD) and have increased IL-10 secretion.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

We prospectively included 20 patients with IVUS-verified TACAD, and 20 patients free of atherosclerotic processes (non-TACAD). IVUS-verified TACAD and non-TACAD was documented 12 month postoperative, and none of these patients had rejection episodes ISHLT 2–3. Some patient demographics/ clinical features are depicted in Table 1. Ten healthy volunteers served as control. Anti-thymocytes globulin (Pasteur Merieux Connaught, Lyon, France) was administered as induction therapy at a dosage of 2 mg/kg body weight per day for the first 7 days after transplantation in a 4 h course. Cyclosporin-A (CyA) was initially injected intravenously, switched to oral application and progressively adjusted to target levels of 250–300 ng/ml. After 1 month CyA was reduced to 200–250 ng/ml. Azathioprine was administered within 24 h post transplantation, and after extubation was given at a dosage of 2 mg/kg. Steroids were given intravenously (500 mg) during prerevascularization of the allograft, and then 375 mg daily for the first week. Oral dosage was initiated by 0·15 mg/kg. All patients received routine lipid lowering therapy and aspirin. Rejection of the allograft was assessed by endomyocardial biopsies, and surveillance performed after 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 weeks, and 3, 6 and 12 months after transplantation. All patients had at time point of blood draw no infection, C-reactive protein levels were below 0·5 mg/dl, and CyA levels ranged from 100 to 150 ng/ml.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features

| non-TACAD | TACAD | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 20 | 20 |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 7·3 | 58 ± 8·3 |

| Gender (m/f) | 14/6 | 12/8 |

| Diagnosis (ICM/DCMP/other) | 8/11/1 | 7/12/2 |

| Duration of ischaemia (min) | 155 ± 45 | 120 ± 60 |

| Therapy | Induction/triple th. | Induction/triple th. |

| Diagnosis TACAD | 12 m postoperative | 12 m postoperative |

Heart catheterization and IVUS

After intracoronary administration of 0·2 mg nitroglycerine, an intravascular ultrasound catheter was pushed into the coronaries, and catheter pullback was performed manually. For longitudinal orientation, septal or diagonal branches were used as anatomic landmarks. HTX recipients were angiographically evaluated after 1·5 or 10 years on regular basis or when they developed angina pectoris.

Cell phenotype

Differential and complete white blood cell count was acquired by Coulter analysis (Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Fluorochrome-labelled monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD95, CD45RO, CD56 or CD19, purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), were used in two and three-colour immunofluorescence staining [9]. Cells were subjected to FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) analyses.

Soluble CD95 (sCD95), soluble CD95 ligand (sCD95L), and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNFR1)

Serum samples obtained from study populations were aliquoted and kept frozen. Circulating sCD95 and sCD95L were measured in a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using polyclonal antibodies against human CD95 and CD95L (Cytoscreen, BioSource International, Inc., Camarillo, CA). The concentration of sTNFR1 (TNFR p55; CD120a) was measured by ELISA using polyclonal antibodies against human TNFR1 (R & D Systems Inc, McKinley Place, MN). The sensitivity of the ELISA for sCD95 and sCD95L was 20 pg/ml, and for sTNFR1 3 pg/ml. The amount of sCD95, sCD95L or sTNFR1 in each serum sample was calculated according to a standard curve.

T cell apoptosis in vivo

A flow cytometric apoptosis detection kit (Becton Dickinson Systems, McKinley, MN) was used to detect programmed cell death. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC; 3 × 105) were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated MoAb to CD3, fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled annexin V (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) to detect phosphatidylserine expression on cells during early apoptotic phases, and 7-aminoactinomycin (7-AAD) dye to exclude dead cells [8]. The samples were analysed on a FACScan 500 (Becton Dickinson).

Activation-induced cell death (AICD)

The amount of 3 × 106 PBMC were placed on 48-well plates and cultured for 18 h at 37°C with MoAb to CD3/CD28 (10 μg/ml) or isotype control antibodies, purchased from Pharmingen. T cells were stained simultaneously with fluorochrome-conjugated MoAb to CD4/7-AAD, and subjected to flow cytometry analysis.

Quantification of histones and of IL-10 by ELISA

Serum samples were obtained from study populations and kept frozen. Soluble histones were measured by a commercial ELISA (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), using MoAb directed against DNA-associated fragments of histones (H1, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4). This allows the specific determination of the cytoplasmic derived mono- and oligonucleosomes in the serum samples.

Circulating serum levels of IL-10 were measured by ELISA using polyclonal antibodies against human IL-10 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The sensitivity of the ELISA is 0·1 pg/ml. The amount of protein in each sample was calculated according to a standard curve of optical density values constructed for known levels of IL-10 protein.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Continuous variables and differences between groups were analysed by anova and Student’s t-test. A value of P < 0·05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Changes in cell immunophenotype

The amount of CD3+ T cells and their CD4 and CD8 subsets in patients with TACAD was not different from non-TACAD patients. The levels of CD3 and CD4 were significantly reduced when compared with the control healthy group (Table 2). Furthermore, the proportion of B lymphocytes (CD19+) and NK cells (CD56+) was significantly increased in TACAD versus non-TACAD patients (P < 0·05 and P < 0·001, respectively).

Table 2.

Changes in the phenotype of peripheral white blood cells

| Cell phenotype | Controls | non-TACAD | TACAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+ (μl) | 1259 ± 118 | 961 ± 97* | 834 ± 103* |

| CD4+ (μl) | 727 ± 87 | 435 ± 39** | 379 ± 47** |

| CD8+ (μl) | 520 ± 53 | 501 ± 70 | 417 ± 78* |

| CD4/8 ratio | 1·42 ± 0·1 | 1·2 ± 0·3* | 1·3 ± 0·3* |

| CD19+ (μl) | 50 ± 10 | 57 ± 10 | 80 ± 35*/† |

| CD56+ (μl) | 77 ± 10 | 82 ± 14 | 167 ± 44**/†† |

Cell type and their subsets in PBMC were identified by immunofluorescence and FACS analysis. Data from non-TACAD (n = 20), TACAD (n = 20) and healthy controls (n = 10) represent the mean ± s.e.m.

Statistical significant differences between cells from non-TACAD or TACAD patients versus control:

P < 0·05

P < 0·001. A significant increase in the amount of CD19 + (B cells) and CD56+ (NK cells) in TACAD versus non-TACAD patients was calculated:

P < 0·05;

P < 0·001, respectively.

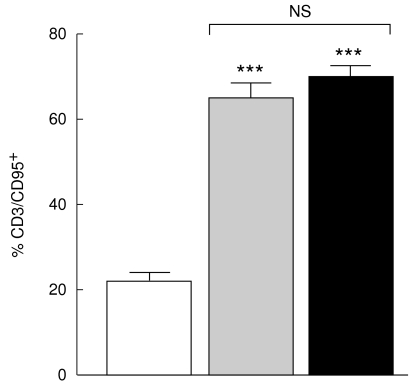

Expression of CD95 and CD45RO on peripheral T cells

The expression of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) was increased to a similar degree in CD3+ T cells from non-TACAD and TACAD (64·3 ± 4·2 and 69·1 ± 2·9%, respectively) patients, as compared with controls (21·8 ± 1·9%). The differences between both non-TACAD and TACAD, and control group were highly significant, P < 0·001 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Expression of CD95. PBMC from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD95 MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. In the percentage of CD95 from non-TACAD (64·3 ± 4·2) and TACAD (69·1 ± 2·9) groups compared with the healthy control (21·8 ± 1·9) a significant increase was calculated: ***P < 0·001. There were no significant (NS) differences between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD95 MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. In the percentage of CD95 from non-TACAD (64·3 ± 4·2) and TACAD (69·1 ± 2·9) groups compared with the healthy control (21·8 ± 1·9) a significant increase was calculated: ***P < 0·001. There were no significant (NS) differences between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

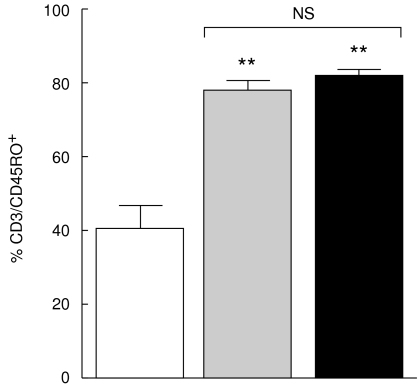

The percentage of cells expressing CD45RO, a T cell memory marker, was up regulated on CD3+ T cells from both non-TACAD and TACAD patient groups (77·5 ± 2·9 and 81·9 ± 1·9%, respectively), as compared with the healthy controls (40·3 ± 6·2%). This differences were significant; P < 0·001 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Expression of CD45RO. PBMC from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD45RO MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. In the percentage of CD45RO from non-TACAD (77·5 ± 2·9) and TACAD (81·9 ± 1·9) groups compared with the healthy control (40·3 ± 6·3) a significant increase was calculated: **P < 0·01. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD45RO MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. In the percentage of CD45RO from non-TACAD (77·5 ± 2·9) and TACAD (81·9 ± 1·9) groups compared with the healthy control (40·3 ± 6·3) a significant increase was calculated: **P < 0·01. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

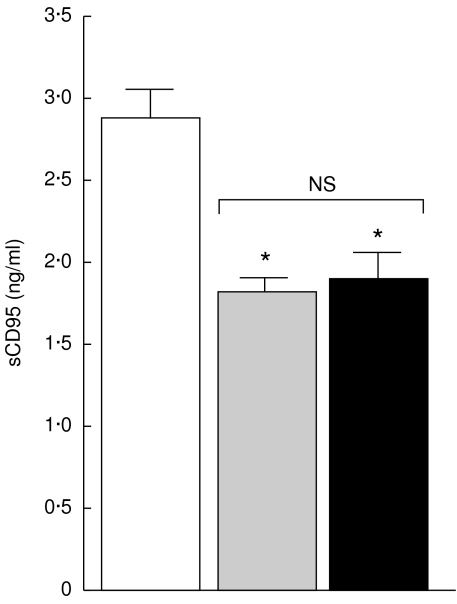

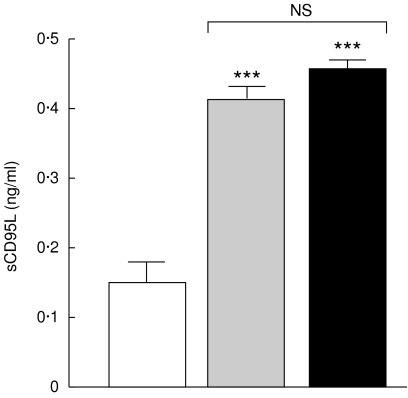

Soluble CD95, sCD95L and sTNFR1

As shown in Fig. 3, the mean serum levels of sCD95 in non-TACAD and TACAD patients (1·8 ± 0·08 and 1·9 ± 0·2 ng/ml, respectively), was significantly reduced (P < 0·05), as compared with that in control volunteers (2·9 ± 0·1 ng/ml). In contrast, as can be seen from Fig. 4, the concentration of sCD95L in non-TACAD as well as in TACAD patients (0·41 ± 0·02 and 0·45 ± 0·012 ng/ml, respectively) was significantly increased (P < 0·001) compared with control (0·15 ± 0·05 ng/ml).

Fig. 3.

Soluble CD95. The concentrations of sCD95 in the sera from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of sCD95 (ng/ml ± s.e.m.). In the concentration of sCD95 in the sera from non-TACAD (1·8 ± 0·08) and TACAD (1·9 ± 0·23) groups compared with the healthy control (2·9 ± 0·17) a significant reduction was calculated: *P < 0·05. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of sCD95 (ng/ml ± s.e.m.). In the concentration of sCD95 in the sera from non-TACAD (1·8 ± 0·08) and TACAD (1·9 ± 0·23) groups compared with the healthy control (2·9 ± 0·17) a significant reduction was calculated: *P < 0·05. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

Fig. 4.

Soluble CD95L. The concentrations of sCD95L in the sera from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of sCD95L (ng/ml ± s.e.m.). In the concentration of sCD95L in the sera from non-TACAD (0·41 ± 0·02) and TACAD (0·45 ± 0·01) groups compared with the healthy control (0·15 ± 0·05) a significant increase was calculated: ***P < 0·001. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of sCD95L (ng/ml ± s.e.m.). In the concentration of sCD95L in the sera from non-TACAD (0·41 ± 0·02) and TACAD (0·45 ± 0·01) groups compared with the healthy control (0·15 ± 0·05) a significant increase was calculated: ***P < 0·001. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

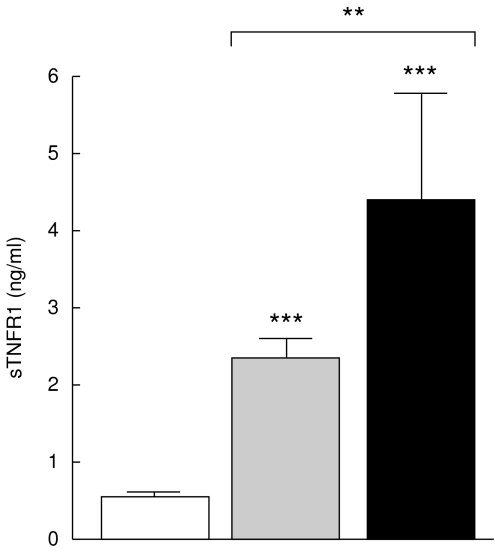

Figure 5 shows an increased concentration of sTNFR1 in the sera from non-TACAD and TACAD patients (2·2 ± 0·2 and 4·4 ± 1·3 ng/ml, respectively), for both groups P < 0·001 as compared with the control (0·53 ± 0·05 ng/ml). Interestingly, the mean serum level of sTNFR1 was significantly lower in non-TACAD versus TACAD patients (P < 0·01).

Fig. 5.

Soluble TNFR1. The concentration of sTNFR1 in the sera from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) was measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of sTNFR1 (ng/ml ± s.e.m.). A significant increase in the concentration of sCD95L in the sera from non-TACAD (2·27 ± 0·23) and TACAD (4·42 ± 1·32) groups compared with the healthy control (0·53 ± 0·05) was calculated: ***P < 0·001. Significant differences at a **P < 0·01 were found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) was measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of sTNFR1 (ng/ml ± s.e.m.). A significant increase in the concentration of sCD95L in the sera from non-TACAD (2·27 ± 0·23) and TACAD (4·42 ± 1·32) groups compared with the healthy control (0·53 ± 0·05) was calculated: ***P < 0·001. Significant differences at a **P < 0·01 were found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

Spontaneous T cell apoptosis in vivo

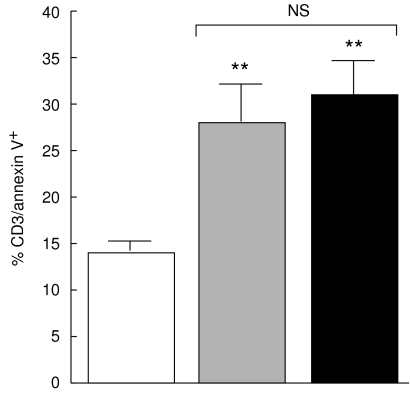

In further experiments we addressed the question whether the elevated state of T cell activation is associated with increased percentage of peripheral T cells undergoing apoptosis. Figure 6 shows that CD3+ T cells from non-TACAD and TACAD patients bind annexin V to a similar extent (28·6 ± 4·4 and 30·9 ± 3·8%, respectively), and these values are significantly higher (P < 0·01) than those of control donors (14·2 ± 1·0%).

Fig. 6.

Spontaneous T cell apoptosis. Freshly isolated PBMC from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-annexin V MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis are expressed as percentage mean ± s.e.m. A significant increase in the percentage of CD3+ stained by annexin V from non-TACAD (28·6 ± 4·4) and TACAD (30·9 ± 3·8) groups compared with the healthy control (14·2 ± 1·0) was calculated: **P < 0·01. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-annexin V MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis are expressed as percentage mean ± s.e.m. A significant increase in the percentage of CD3+ stained by annexin V from non-TACAD (28·6 ± 4·4) and TACAD (30·9 ± 3·8) groups compared with the healthy control (14·2 ± 1·0) was calculated: **P < 0·01. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

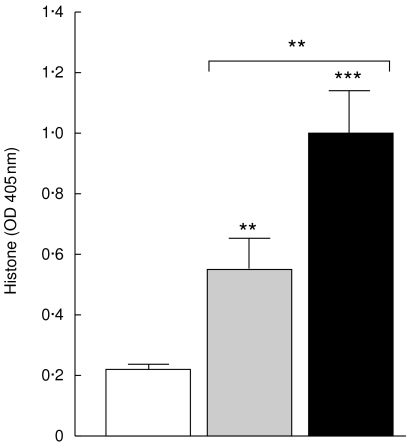

Histones content

The results presented in Fig. 7 show lower concentration of histones in the sera from non-TACAD than from TACAD patients (P < 0·01), and histone concentration from both groups was higher than that of controls (0·22 ± 0·1; P < 0·01 and P < 0·001, respectively).

Fig. 7.

Soluble histones. The concentration of soluble histones in the sera from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) was measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of histones in arbitrary units ± s.e.m. In the sera from non-TACAD (0·56 ± 0·1) and TACAD (0·99 ± 0·2) groups compared with the healthy control (0·22 ± 01) a significant increase in the concentration of histones was calculated: **P < 0·01 and ***P < 0·001, respectively. Significant differences at a **P < 0·01 were found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) was measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of histones in arbitrary units ± s.e.m. In the sera from non-TACAD (0·56 ± 0·1) and TACAD (0·99 ± 0·2) groups compared with the healthy control (0·22 ± 01) a significant increase in the concentration of histones was calculated: **P < 0·01 and ***P < 0·001, respectively. Significant differences at a **P < 0·01 were found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

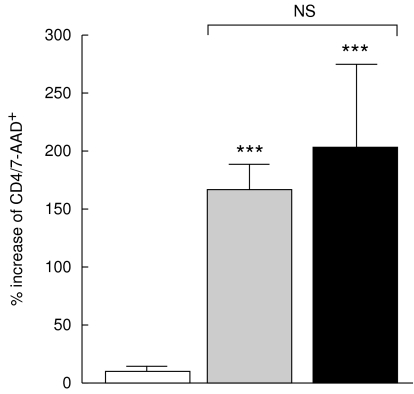

Susceptibility to AICD after T cell receptor involvement

As shown in Fig. 8, the potency of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies to induce AICD was markedly elevated in the non-TACAD and TACAD study group (166·4 ± 23·5 and 204·7 ± 72·6%, respectively) versus control (7·8 ± 6·3%). The difference in the percentage of CD4/7-AAD+ cells from non-TACAD and TACAD patients cultured for 18 h with anti-CD3/CD28 MoAb was not significant.

Fig. 8.

Antibodies-induced cell dead (AICD). PBMC from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were cultured for 18 h with IgG control or MoAb to CD3/CD28, and stained with anti-CD4 and anti-7-AAD MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis represent an increase in the percentage of CD4 cells stained by 7-AAD, relative to IgG control. The results obtained with cells from non-TACAD (166·4 ± 23·5) and TACAD (204·7 ± 72·6) patients were significantly increased (***P < 0·001), as compared with the healthy control (7·8 ± 6·3). There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) were cultured for 18 h with IgG control or MoAb to CD3/CD28, and stained with anti-CD4 and anti-7-AAD MoAb. Data from two-colour immunofluorescence and FACS analysis represent an increase in the percentage of CD4 cells stained by 7-AAD, relative to IgG control. The results obtained with cells from non-TACAD (166·4 ± 23·5) and TACAD (204·7 ± 72·6) patients were significantly increased (***P < 0·001), as compared with the healthy control (7·8 ± 6·3). There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

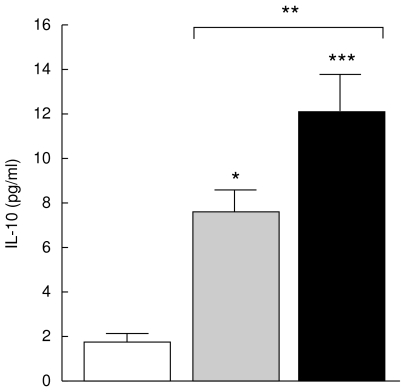

Interleukin-10

The Th1 subset is selectively susceptible towards programmed cell death, which leads to a predominance of Th2 cytokine production. As shown in Fig. 9, the mean serum level of IL-10 was significantly increased in TACAD (12·1 ± 1·7 ng/ml) than in non-TACAD (7·6 ± 1·06 ng/ml, P < 0·001) patients. The concentration of IL-10 in both groups of patients was higher that in controls (1·8 ± 0·4 ng/ml).

Fig. 9.

IL-10 production. The concentration of IL-10 in the sera from non-TACAD ( n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) was measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of IL-10 (pg/ml ± s.e.m.). In the concentration of IL-10 in the sera from non-TACAD (7·6 ± 1·1) and TACAD (12·1 ± 1·7) group, compared with the healthy control (4·5 ± 1·8) a significant increase was calculated: **P < 0·01 and ***P < 00·1, respectively. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

n = 20) and TACAD (▪ n = 20) patients, and from healthy controls (□ n = 10) was measured by ELISA. The results represent the mean of IL-10 (pg/ml ± s.e.m.). In the concentration of IL-10 in the sera from non-TACAD (7·6 ± 1·1) and TACAD (12·1 ± 1·7) group, compared with the healthy control (4·5 ± 1·8) a significant increase was calculated: **P < 0·01 and ***P < 00·1, respectively. There were no significant (NS) differences found between non-TACAD and TACAD groups.

DISCUSSION

In this report we have shown that IVUS-verified TACAD is associated with increased T cell apoptosis in vivo and enhanced pronicity to undergo AICD in vitro. Moreover, a Th2 type pattern of cytokine, as shown by IL-10 production, was accompanied by quantitative increased B cell compartment in patients with TACAD (see Table 1). It has been shown previously that IL-2 producing Th1 cells are selectively susceptible to AICD following CD95 engagement. The Th2 subset of CD4+ cells, appear to be resistant to this special type of apoptosis [10,11], which in transplant recipients may be caused by up-regulation of protective molecules such as Bcl-HL and Bag-1 [12]. Since autoimmune disease patients demonstrate excessive T cell apoptosis [13,14], together with reduced Th1-like cytokines (IL-2, IL-12 and IFN-γ) production and increased Th2 cytokine (IL-4, IL-10) profile [15,16], HTX patients with TACAD immune reactivity seem to resemble a smouldering picture similar to autoimmune diseases.

Maintenance of T cell homeostasis and peripheral tolerance to self-antigens following repeated lymphocyte stimulations is mainly regulated by apoptosis. Apoptosis is initiated and controlled by a large number of professional death receptors of the TNF receptor superfamily and their corresponding ligands [17]. One of the best-characterized death receptors is CD95/APO-1/Fas. Following cross-linking of CD95, the cytoplasmic domain of this receptor, so-called death domain, is responsible for the transduction of the apoptotic signal into the cell [18,19]. The Bcl-2 family of proteins, which contains pro-apoptotic members like Bax, Bak and Bad, and anti-apoptotic members like Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, tightly regulates the death machinery [17].

An increased in vivo IL-10 production was demonstrated in TACAD, and to a lower extent also in non-TACAD patients. The role of IL-10 in pathophysiology of vasculopathy is not well understood. IL-10 has been identified as a cytokine capable to suppress multiple activity of the immune response [20]. In vitro studies have shown that IL-10 prevents antigen-specific T cell proliferation by reducing MHC class II antigen expression on antigen presenting cells, and suppressing IL-2 production by Th1 cells [21,22]. In patients with severe combined immunodeficiency transplanted with HLA mismatched haematopoietic stem cells, elevated IL-10 production was associated with tolerance induction [23].

In addition to the classical DNA fragmentation that accompanies cellular apoptosis, a consequence of cell activation following CD95 legation is the export of phosphatidylserine from the inner leaflet to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane [24]. Translocation of phosphatidylserine to the external cell surface occurs during apoptosis as well as necrosis, and facilitates the specific recognition and engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages [25]. Annexin V binding is indicative for early stage of apoptosis, before the loss of cell membrane integrity. By contrast, in necrosis the cell membrane looses its integrity and becomes leaky, and this may be visualized by 7-AAD staining, a dye indicative for necrosis.

The granzyme A is a specific triptase which synergistically enhances DNA fragmentation induced by the caspase-activator granzyme E, leading to complete degradation of histone H1, and cleaves core histones into 16 kDa fragments [26]. In apoptotic cells, double-stranded cleavage DNA generate mainly long chromatin fragments, H1-rich oligonucleosomes bound to the nucleus, and short oligonucleosomes and mononucleosomes which are not attached to the nucleus [27]. In line with these data, in the present study, the amount of histones was significantly increased in the sera from non-TACAD, and even more evidently from TACAD patients.

TNF is a proinflammatory cytokine produced during infection, tissue injury or invasion, and probably is the most potent molecule that signal apoptosis. TNF activated both cell-survival and cell-death mechanisms simultaneously. Activation of NF- B-dependent genes regulates the survival and proliferative effects of TNF, whereas activation of caspases regulates the apoptotic pathway [28]. TNF, like other cytokines, exerts its biological function by binding to specific, high affinity cell receptors. Two types of TNF receptors, type I (TNFR1; TNFR-p55; CD120a) and type 2 (TNFR2; TNFR-p75; CD120b) have been identified and characterized [29]. Cleaved fragments of both TNFR1 and TNFR2 may mediate the host immune response, in a cytokine-like manner, and determine the course and outcome of the disease by interacting with TNF and competing with highly polymorphic receptors. Recently, plasma concentration of sTNFR1 increased significantly during cardiopulmonary bypass [30]. Therefore, sTNFR are considered as parameters of cell-mediated activation, and their measurement may have diagnostic value for monitoring post-transplant allograft and predicting immunological complications such as rejection or infection causing postoperative morbidity. In our study, particularly intriguing was the high level of TNFR1 shedding in patients with TACAD. This suggests augmented TNF-α gene transcription and cytokine production, as shown in monocytes after stimulation with lipopolysaccaride via CD14/LPS receptor [31]. Since monocytes could phagocytose apoptotic cells via CD14 antigen [32], and binding of TNF-α to TNFR1 augments the FADD/FLICE-dependent cell death pathway [33,34], a vicious cycle may be set up in TACAD susceptible patients culminating in accelerated apoptosis of CD4+ Th1 cells.

Our study show that TACAD patients may serve as a model for disease with augmented T cell reactivity to alloantigens and/or autoantigens, an increase in the expression and secretion of death receptors, heightened production of IL-10, and susceptibility of Th1 cells to undergo AICD. A further progress in understanding the mechanisms which control programmed cell death may help to develop new therapy protocols for transplant vasculopathy.

Acknowledgments

Dr HJ Ankersmit designed the study. This work was supported by research grant Nr 8290 of Austrian National Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weis M, von Scheidt W. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a review. Circulation. 1997;96:2069–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranda JM, Hill J. Cardiac transplant vasculopathy. Chest. 2000;118:1792–800. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.6.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young JB. Allograft vasculopathy: diagnosing the nemesis of heart transplantation. Circulation. 1999;100:458–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon D. Transplant atherosclerosis. In: Fuster V, Ross R, Topol EJ, editors. Atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 715–26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fateh-Moghadam S, Bocksch W, Ruf A, et al. Changes in surface expression of platelet membrane glycoproteins and progression of heart transplant vasculopahty. Circulation. 2000;102:890–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulligan MS, Warner RL, McDuffie JE, et al. Regulatory role of Th-2 cytokines, IL-10 and IL-4, in cardiac allograft rejection. Exp Mol Pathol. 2000;69:1–9. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2000.2304. 10.1006/exmp.2000.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liuzzo G, Goronzy JJ, Yang H, et al. Monoclonal T-cell proliferation and plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2000;101:2883–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ankersmit HJ, Tugulea S, Spanier T, et al. Activation-induced T-cell death and immune dysfunction after implantation of left-ventricular assist device. Lancet. 1999;354:550–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ankersmit HJ, Deicher R, Moser B, et al. Impaired T cell function, increased soluble death-inducing receptors, and activation-induced T cell death in patients undergoing haemodialysis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:142–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledru E, Lecoer H, Garcia S, Debord T, Cougeon ML. Differential susceptibility to activation-induced apoptosis among peripheral Th1 subsets: correlation with Bcl-2 expression and consequences for AIDS pathogenesis. J Immunol. 1998;160:3194–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varadhachary AS, Pedrow SN, Hu C, Ramanarayanan M, Salgame P. Differential ability of T cell subsets to undergo activation-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5778–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ke B, Ritter T, Kato H, et al. Regulatory cells potentiate the efficacy of IL-4 gene transfer by up-regulating Th2-dependent expression of protective molecules in the infectious tolerance pathway in transplant recipients. J Immunol. 2000;164:5739–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mysler E, Bini P, Drappa J, et al. The apoptosis-1/Fas protein in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1029–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI117051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeher M, Szodoray P, Gyimesi E, Szondy Z. Correlation of increased susceptibility to apoptosis of CD4+ T cells with lymphocyte activation and activity of disease in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1673–81. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1673::AID-ANR16>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funauchi M, Ikoma S, Enomoto H, Horiuchi A. Decreased Th-1-like and increased Th2-like cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 1998;27:219–24. doi: 10.1080/030097498440859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz DA, Gray JD, Behrendsen SC, et al. Decreased production of interleukin 12 and other Th-1 type cytokines in patients with recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:838–44. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<838::AID-ART10>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krammer PH. CD95 (APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis: live and let die. Adv Immunol. 1999;71:163–210. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boldin MP, Varfolomeev EE, Pancer Z, et al. A novel protein that interacts with the death domain of Fas/APO-1 contains a sequence motif related to the death domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7795–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzio M, Chinnaiyan AM, Kischkel FC, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death-inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore KW, O’Gaara A, de Waal Malefyt R, Vieira P, Mosmann TR. Interleukin-10. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:165–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, et al. IL-10 and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via down-regulation of class II MHC expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spittler A, Schiller C, Willheim M, et al. IL-10 augments CD23 expression on U937 cells and down-regulates IL-4-driven CD23 expression on cultured human blood monocytes: Effects of IL-10 and other cytokines on cell phenotype and phagocytosis. Immunology. 1995;85:311–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacchetta R, Bigler M, Touraine J-L, et al. High levels of interleukin-10 production in vivo are associated with tolerance induction in SCID patients transplanted with HLA mismatched hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:493–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin SJ, Reutelingsperger CP, McGahon AJ, et al. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1545–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, et al. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang D, Pasternack MS, Beresford PJ, et al. Induction of rapid histone degradation by the cytotoxic T lymphocyte protease granzyme A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3683–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang D, Zheng L, Leonardo MJ. Caspases and T-cell receptor-induced thymocyte apoptosis. Cell Death Diff. 1999;6:402–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. Regulated commitment of TNF receptor signaling: a molecular switch for death or activation. Immunity. 1999;11:783–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Leonardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies. Integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marano CW, Garulacan LA, Laughlin KV, et al. Plasma concentrations of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and tumor necrosis factor during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1313–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01932-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson AG, Symons JA, McDowell TL, McDevitt HO, Duff GW. Effects of a polymorphism in the human tumor necrosis factor alpha promotor on transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3195–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlegel RA, Krahling S, Callahan MK, Williamson P. CD14 is a component of multiple regulation systems used by macrophages to phagocytose apoptotic lymphocytes. Cell Death Diff. 1999;6:583–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Louis E, Franchimont D, Piron A, et al. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) gene polymorphism influences TNF-alpha production in lipopoysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated whole blood cell culture in healthy humans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:401–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00662.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chinnaiyan AM, Tepper CG, Seldin MF, et al. FADD/MORT1 is a common mediator of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) and tumor necrosis factor receptor-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4961–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]