Abstract

The regulatory effect of prostaglandin (PG) E2 and a cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor on Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG)-induced macrophage cytotoxicity in a bladder cancer cell, MBT-2, was studied in vitro. BCG stimulated thioglycollate-elicited murine peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) to induce cytotoxic activity and to produce cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and PGE2. NS398, a specific COX-2 inhibitor, and indomethacin (IM), a COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor, enhanced viable BCG-induced cytotoxic activity and IFN-γ and TNF-α production of PEC. However, NS398 and IM did not enhance these activities induced by killed BCG. Enhanced cytotoxicity was mediated by increased amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Exogenous PGE2 reduced cytotoxic activity and IFN-γ and TNF-α production of PEC. These results suggest that PGE2 produced by BCG-activated macrophages has a negative regulatory effect on the cytotoxic activity of macrophages. Accordingly, a PG synthesis inhibitor may be a useful agent to enhance BCG-induced antitumour activity of macrophages.

Keywords: BCG, bladder cancer, cytotoxicity, prostaglandin E2, macrophage

INTRODUCTION

Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) has proved to be effective in immunotherapy for bladder cancer [1,2[, but its antitumour mechanism is not fully understood. There have been several reports that BCG stimulates cytotoxic activity of macrophages, T cells and NK cells [3,4]. The activated effector cells kill target cells by both non-specific soluble factors and direct cell to cell contact. It is reported that patients who failed in BCG immunotherapy showed a higher antibody response to BCG heat-shock proteins in their sera [5] and higher levels of interleukin (IL)-6 and/or IL-10 in the urine of patients [6]. These studies indicate that Th2 immune responses are more easily induced than Th1 immune responses during BCG-immunotherapy and suppress cellular immune responses. It is reported that prostaglandin (PG) inhibits the production of Th1 type cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-12, favouring the production of Th2-type cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-5 by human lymphocytes [7]. PGE2 suppressed the activation of NK cells, lymphokine-activated killer cells and cytotoxic T cells by inhibiting IL-2 receptor expression on effector cell surfaces [8]. Recently, we also found that PGE2 suppressed IFN-γ and IL-12 production by macrophages (9).

PGs are synthesized from cell membrane phospholipids by way of arachidonic acid. Two types of enzyme, cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and -2, are known to mediate this pathway [10]. COX-1 is an enzyme that is constitutively expressed in many types of tissues and is not significantly up-regulated by external stimuli. On the other hand, COX-2 is an inducible enzyme that is up-regulated by several internal or external stimuli such as lipopolysaccharides [11] and IL-1β [12]. Therefore, COX-1 and -2 are considered to play an important role in the production of PGs at inflammation sites.

Little is known about the expression of COX and the production of PGs in BCG-stimulated macrophages. To investigate the role of PGs in BCG-induced macrophage activities we used NS398, a COX-2 specific inhibitor, and indomethacin (IM), a COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor. This study demonstrates that PGs regulate BCG-induced macrophage antitumour activity negatively, while COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors augment its activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The culture medium was RPMI-1640 (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) containing 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), l-glutamine (2 mm) and penicillin-G (100 U/ml) (Grand Island Biological Co., Grand Island, NY, USA). PGE2 and IM were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA. NS398 was purchased from Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MA, USA. Anti-Pan-NK cell monoclonal antibody (MoAb), clone DX5 and anti-IFN-γ MoAb, clones R4–6A2, XMG1·2, were purchased from Pharmingen Co., San Diego, CA, USA. Anti-TNF-α mAb, clone G281-2626, was purchased from Dainihon Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan. Anti-Thy1·2 MoAb, clone F7D5, was purchased from Serotec Ltd, Oxford, UK. Low toxic rabbit complement was purchased from Cosmobio Co., Tokyo, Japan.

Animals

Female C3H/HeN mice were purchased from Seac Co., Ohita, Japan, maintained for at least 1 week in our laboratory and were then used for experiments at 6–8 weeks of age. All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines for the care and use of animals approved by the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan.

BCG and culture medium

BCG (Tokyo 172 strain) were kindly supplied by Japan BCG Production Co., Tokyo, Japan and were grown to the mid-log phase in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI, USA) supplemented with the following enrichment: 10% albumin-dextrose-catalase (ADC) (Difco Laboratories Inc.), 0·2% glycerol and 0·5% Tween 80. The grown bacteria were washed and suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7·4. The concentration of the bacteria suspension was adjusted spectrophotometrically at a 590-nm wave length. Killed BCG was prepared by heating the viable bacteria at 121°C for 30 min. After extensive washing of killed bacteria with PBS, the concentration was adjusted equal to that of viable BCG. Viability was tested by culturing on 7H10 agar and Ziehl–Neelsen staining confirmed that the structure of bacteria was intact.

Target cell for cytotoxicity

The target cell used in this study was N-[4-(5-nitro-2-furyl)-2-thiazolyl] formamide (FANFT)-induced transitional cell carcinoma, MBT-2, from C3H/HeN mice [13].

In vitro culture of peritoneal exudate cells (PEC)

PEC were harvested from C3H/HeN mice that had been injected i.p. with 2 ml of 5% thioglycollate (Difco Laboratories Inc.) medium 3 days previously. Cells were collected by washing out the peritoneal cavity with PBS. PEC were composed of more than 90% macrophages and less than 10% lymphocytes by flow cytometric analysis. After washing several times with PBS, the cells were suspended in RPMI 1640–10% FCS medium. One hundred μl of PEC (1 × 105 cells/well) suspension were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed microtitre culture plates (Falcon #3072, Becton Dickinson Co., Frankline Lake, NJ, USA). After 2h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air, BCG (1 × 105 bacilli/well) and/or other agents were added, and final volumes in wells were adjusted to 200 μl. The culture supernatants were harvested after 12 h (for TNF-α) or 24 h (for IFN-γ). As a preliminary experiment, we confirmed that these culture periods were best for the assay of each cytokine. The amounts of IFN-γ in the culture supernatants were assayed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using capture MoAb, biotinylated detection MoAb, streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase and p-nitrophenyl-phosphate as a substrate (Zymed Laboratory Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). PGE2 was assayed with an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (Cayman Chemical Co.) [9]. TNF-α was measured by a L929 bioassay [14].

Depletion of T cells and NK cells from PEC

PEC (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well flat-bottomed culture plates (Falcon #3072) at 37°C for 1h in 5% CO2 and 95% air. After that, anti-Thy-1 and/or anti-NK MoAb with complement were added to each well and cultured for a further 2 h. Non-adherent cells and dead cells were removed by aspirating the media. These treated PEC, composed of more than 98% Mac-1(+) cells and less than 2% T cells and NK cells as detected by a flowcytometry, were used for the following experiments.

Cytotoxicity assay

One hundred μl of PEC (1 × 105 cells/well) suspension were seeded in 96-well flat-bottomed microtitre culture plates. After 2 h culture, BCG (1 × 105 bacilli/well) and/or other agents were added, and final volumes in wells were adjusted to 200 μl and incubated at 37°C for 12 h in 5% CO2 and 95% air. MBT-2 murine bladder cancer cells were radiolabelled with 100 μCi of [51Cr]sodium chromate (NEN Life Science Co., Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C for 12 h in 5% CO2 and 95% air. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS, detached by 0·25% trypsin (Difco Laboratories Inc.) and suspended at a concentration of 1 × 105/ml in RPMI-10% FCS medium. Fifty μl of 51Cr-labelled target cells (5 × 103 cells/well) suspension were added to 96-well flat-bottomed microtitre culture plates containing 200 μl of effector cells which had been incubated with several agents for 12 h. After a further 20h incubation, the supernatants were harvested and released 51Cr was counted with a gamma counter.

For the experiment using culture inserts, PEC (5 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in 1 ml of medium in 24-well flat-bottomed microtitre culture plates (Falcon #3047) and 51Cr-labelled target cells (2·5 × 104 cells/well) in 250 μl medium were added in the presence or absence of a cell culture insert (Falcon #3095). All assays were performed in triplicate. Spontaneous 51Cr release was determined by incubating radiolabelled target cells in the absence of PEC. Maximal 51Cr release was determined by incubating the same amount of target cells in 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma Chemical Co.). The percentage of specific cytotoxicity was calculated as follows:

%(cytotoxicity) = [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximal release − spontaneous release)] × 100

Statistical analysis

All determinations were made in triplicate and each result was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Statistical significance was determined by paired Student’s t-test. A P-value of 0·05 or less was considered significant [15].

RESULTS

Cytotoxic activity and cytokine production of PEC stimulated with BCG plus a COX inhibitor

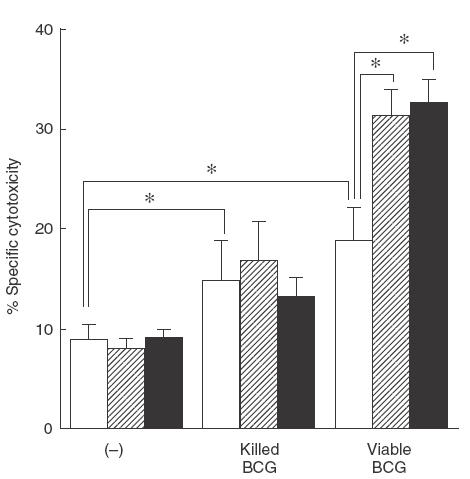

Since PG is reported to have suppressive activity on cellular immunity, we studied the effect of inhibitors of PG synthesis, NS398 and IM, on BCG-induced PEC cytotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 1, BCG enhanced PEC-mediated cytotoxicity. Viable BCG enhanced PEC-mediated cytotoxicity more efficiently than killed BCG. In addition, NS398 and IM further enhanced viable BCG-induced cytotoxicity. There was no significant difference between the enhancing effect of NS398 and IM. Interestingly, NS398 and IM did not enhance killed BCG-induced cytotoxicity. Neither NS398 nor IM alone enhanced PEC-mediated cytotoxicity without BCG. The amount of PGE2 in the culture supernatant is shown in Table 1. PEC without stimulators did not produce a detectable amount of PGE2. However, BCG stimulated PEC to produce PGE2. Viable BCG stimulated PEC more efficiently to produce PGE2 than killed BCG. NS398 and IM (1 μm) completely diminished PGE2 production. This suggests that PGE2 produced by PEC stimulated with both killed and viable BCG depends on both COX-1 and COX-2.

Fig. 1.

Effect of NS398 or IM on cytotoxicity of PEC stimulated with BCG against MBT-2 cells. PEC (1 × 105) were treated with killed or viable BCG (1 × 105) in the absence or presence of NS398 or IM (1 μm) for 12 h, cultured with 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 for a further 20 h, and then the released 51Cr in the supernatants was counted. The effector/target ratio was 20/1. The results are expressed as the percentage specific killing of MBT-2 cells ± s.d. of triplicate cultures. *Significantly enhanced. □, (−);  , NS398; ■, IM.

, NS398; ■, IM.

Table 1.

Cytokine and prostaglandin production of PEC stimulated with killed and viable BCG and COX inhibitors1

| Stimulator | Agents (1μm) | IFN-γ (pg/ml) | TNF-α (U/ml) | PGE2 (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−) | (−) | <32 | <100 | <0·01 |

| NS398 | <32 | <100 | <0·01 | |

| IM | <32 | <100 | <0·01 | |

| Killed BCG | (−) | 118 ± 9 | <100 | 2·2 ± 0·4* |

| NS398 | 211 ± 22* | <100 | <0·01 | |

| IM | 183 ± 17* | <100 | <0·01 | |

| Viable BCG | (−) | 967 ± 31 | 1028 ± 21 | 4·8 ± 0·7* |

| NS398 | 2117 ± 124* | 1200 ± 105* | <0·01 | |

| IM | 2429 ± 64* | 1448 ± 172* | <0·01 |

PEC were cultured with killed or viable BCG in the presence or absence of NS398 or IM for 12 h (for TNF-α) or for 24 h (for IFN = γ and PGE2), and cytokines and PGE2 in the culture supernatant were assayed. The results are expressed as mean ± s.d. of thriplicate cultures.

Significantly increased from the control group.

To study the mechanism of COX inhibitor-induced enhancement of BCG-induced cytotoxicity, we measured cytokines in the culture supernatant. As shown in Table 1, viable BCG markedly stimulated PEC to induce IFN-γ and TNF-α. NS398 and IM further enhanced viable BCG-induced cytokine production. PEC stimulated with killed BCG only slightly induced IFN-γ, but not TNF-α production in the presence and absence of NS398 and IM. NS398 and IM alone did not enhance these productions.

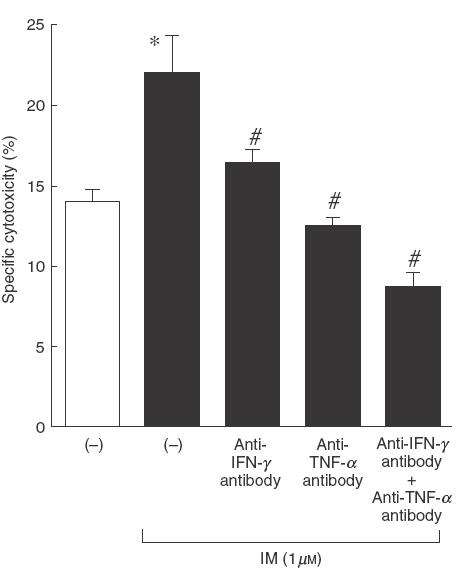

Anti-IFN-γ and/or TNF-α antibodies reduced cytotoxicity of PEC stimulated with BCG plus a COX inhibitor

To determine more directly the participation of IFN-γ and TNF-α in COX inhibitor-induced enhancement of cytotoxic activity, we added anti-IFN-γ and/or anti-TNF-α antibody to the culture with BCG plus a COX inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 2, anti-IFN-γ, and especially anti-TNF-α antibody, significantly reduced the cytotoxicity of PEC against MBT-2. The combination of both antibodies completely inhibited the cytotoxicity to below the control level. Both IFN-γ and TNF-α in the culture supernatant were also diminished by these two antibodies (data not shown). These results indicate that the enhanced cytotoxicity of PEC induced with a COX inhibitor is mediated by enhanced production of IFN-γ and TNF-α.

Fig. 2.

Effect of anti-IFN-γ and/or anti-TNF-α antibody on cytotoxicity of PEC stimulated with BCG and a COX inhibitor. PEC (1 × 105) were stimulated with viable BCG (1 × 105) plus IM (1 μm) in the presence or absence of anti-IFN-γ (5 μg/ml) and/or anti-TNF-α (5 μg/ml) antibody for 12h in 96-well plates, and then 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 cells were seeded onto the effector cells. After a further 20 h incubation, released 51Cr in the supernatants was counted. The effector/target ratio was 20/1. *Significantly increased from IM(−) group. #Significantly decreased from antibody (−) group.

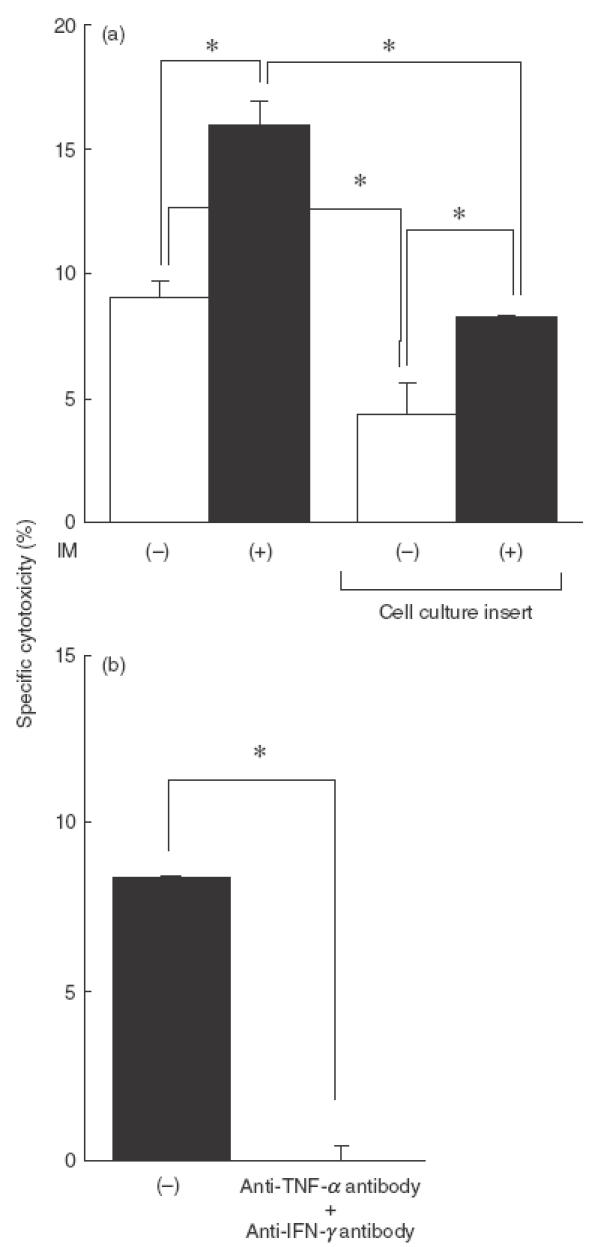

To clarify the role of soluble factors in COX inhibitor-enhanced cytotoxicity, we used a cell culture insert to separate target cells from effector cells and assayed its cytotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 3a, in the presence of the cell culture insert the cytotoxic activity was diminished by about 50%. This means that BCG-induced cytotoxicity depends on both soluble factors and direct cell-to-cell killing. Cytotoxicity was again enhanced by BCG with a COX inhibitor both in the absence and presence of the cell culture insert. As shown in Fig. 3b, COX inhibitor-enhanced cytotoxicity in the presence of the cell culture insert was completely inhibited by the combination of anti-IFN-γ and anti-TNF-α antibody. These results suggest that BCG-induced cytotoxicity enhanced by a COX inhibitor was mediated mainly by soluble factors such as IFN-γ and TNF-α. In fact, exogeneous IFN-γ and TNF-α killed MBT-2 directly in a dose-dependent manner, while the cytotoxic activity of IFN-γ or TNF-α alone was marginal (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Cytotoxic activity of PEC stimulated with BCG and a COX inhibitor in the presence of the culture insert. (a) PEC (5 × 105) were cultured with viable BCG (5 × 105) plus IM (1 μm) for 24 h in 24-well plates, and then 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 cells were seeded onto the effector cells directly or indirectly using the cell culture insert. (b) PEC (5 × 105) were cultured with viable BCG (5 × 105) plus IM (1 μm) in the presence or absence of anti-IFN-γ (5 μg/ml) and/or anti-TNF-α (5 μg/ml) antibody for 12 h in 24-well plates, and then 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 cells were seeded into the cell culture insert. After a further 20 h incubation, released 51Cr in the supernatants was counted. The effector/target ratio was 20/1. *Significantly different.

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxic activity of IFN-γ and TNF-α on MBT-2 cells. 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 cells (5 × 105) were cultured with various concentrations of IFN-γ, TNF-α or IFN-γ/TNF-α for 20h and released 51Cr in the supernatant was counted. *Significantly killed. □, IFN-γ, ◊, TNF-α; •, IFN-γ + TNF-α.

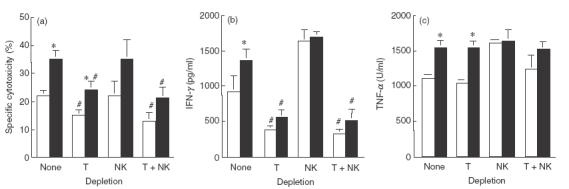

Cytotoxic activity in T cells and NK cells-depleted PEC stimulated with BCG and a COX inhibitor

We depleted T cells and NK cells by antibody plus complement treatment, to study the participation of T cells and NK cells in BCG and COX inhibitor-induced cytotoxicity of PEC. The depletion of T cells decreased the cytotoxicity about by 30%, but the depletion of NK cells had no effect on the cytotoxicity in the presence or absence of a COX inhibitor (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α was also reduced by T cell depletion, but not by NK cell depletion. These results suggest that T cells play some roles in the expression of cytotoxicity of PEC induced with BCG and a COX inhibitor.

Fig. 5.

Cytotoxic activity and cytokine production of T cell and/or NK cell-depleted PEC. (a) PEC (1 × 105) were cultured in 96-well culture plates for 1h, treated with anti-Thy-1·2 and/or anti-NK antibody with a complement for 2 h, then the media were removed and replaced with fresh media. These treated PEC were stimulated with BCG (1 × 105) in the presence (■) or absence (□) of IM (1 μm) for 12 h, and then 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 cells were added. After a further 20h incubation, released 51Cr in the supernatants was counted. (b) IFN-γ production in the supernatant was assayed 24h after BCG stimulation. (c) TNF-α production in the supernatant was assayed 12 h after BCG-stimulation. *Significantly increased from IM (−) group. #Significantly decreased from non-depleted group.

Exogenous PGE2 suppresses BCG-induced cytotoxicity and cytokine production

To elucidate further the role of PGE2 in viable BCG-induced cytotoxicity, the effect of exogenous PGE2 on the cytotoxicity of PEC stimulated with viable BCG was studied. As shown in Fig. 6a, IM again enhanced cytotoxicity of BCG-treated PEC, while PGE2 reduced the cytotoxicity of IM and BCG-treated PEC in a dose-dependent manner. Exogenous PGE2 also suppressed IFN-γ and TNF-α production by IM and BCG-treated PEC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6b,c).

Fig. 6.

Effect of exogenous PGE2 on cytotoxicity and cytokine production of PEC stimulated with viable BCG against MBT-2 cells. (a) PEC (1 × 105) were treated with viable BCG (1 × 105) in the absence or presence of IM (1 μm) and various concentrations (1–100 nm) of exogenous PGE2 for 12 h, incubated with 51Cr-labelled MBT-2 for a further 20 h, and then the released 51Cr in the supernatants was counted. The effector/target ratio was 20/1. (b) IFN-γ production in the supernatant was assayed 24 h after BCG-stimulation. (c) TNF-α production in the supernatant was assayed 12 h after BCG-stimulation. *Significantly increased from IM (–) group. #Significantly decreased from PGE2 (–) group.

DISCUSSION

It is reported that infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis or M. bovis BCG induces PGs in human monocytes [16]. PGs inhibited immune effector cell functions such as the activity of cytotoxic T cells, NK cells and macrophages in a Mycobacterium infection model [17]. Other groups reported that arachidonic acid metabolites had immunosuppressive effects on mouse splenic macrophages infected with Mycobacterium [18]. In particular, PGE2 produced at the early stage of infection inhibited TNF-α production in macrophages [19]. To elucidate the role of PGE2 in BCG-induced macrophage cytotoxicity, we studied the effect of COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors on the cytotoxic activity of BCG-activated macrophages against murine bladder cancer cells in vitro.

We found that two COX inhibitors, NS398 and IM, enhanced the cytotoxic activity of PEC stimulated with viable BCG, but did not enhance the cytotoxicity induced with killed BCG (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in the enhancing activity on BCG-induced cytotoxicity between NS398 and IM. PEC stimulated with viable BCG produced large amounts of PGE2. However, the amount of PGE2 produced by killed BCG-treated PEC was about half that of viable BCG-treated PEC (Table 1). Exogenous PGE2 reduced viable BCG-induced cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that the endogenous PGE2 produced by BCG-activated macrophages down-regulates BCG-induced macrophage cytotoxicity.

In a previous paper we have reported that BCG-induced macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity was regulated by soluble factors such as IFN-γ and TNF-α [20]. We also found that IFN-γ and TNF-α production by PEC were down-regulated by PGE2 and up-regulated by COX inhibitors (Fig. 6 and Table 1). The enhanced cytotoxicity of BCG-treated PEC by COX inhibitors was also reduced by the depletion of T cells and NK cells (Fig. 5). The participation of T cells and NK cells in this experiment seems to be mediated by cytokines such as IFN-γ, because cytokine production was also reduced by T cells and NK cells depletion and MBT-2 cells were not susceptible for T cells and NK cells.

It is reported that IL-12 is produced mainly by macrophages, playing an important role in the induction of IFN-γ production by T cells and NK cells. Furthermore, it was reported that PGE2 was a potent inhibitor of IL-12 production [21,22]. In our study, IL-12 production by BCG-treated macrophages was down-regulated by exogenous PGE2 as well as IFN-γ and TNF-α, but not enhanced by COX inhibitors (data not shown).

The important finding in this study is the difference between viable and killed BCG for the induction of macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity and PGE2. Viable BCG induced macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity and produced IFN-γ, TNF-α and PGE2 more efficiently than killed BCG. This seems to be caused by the longer survival of BCG in macrophages which can stimulate macrophages continuously.

PGE2 plays an important role in the induction of inflammation and regulates negatively immune responses. Accordingly, depletion of PGE2 results in the diminution of inflammation and the enhancement of immune responses such as cytokine production, as shown in this report. When PEC were stimulated with killed BCG, PGE2 was also produced, but its amount was about half that induced with viable BCG. Killed BCG did not stimulate IFN-γ and TNF-α production significantly (Table 1), but antitumour activity was almost the same as viable BCG (Fig. 1). However, NS398 and IM did not enhance antitumour activity and cytokine productions of killed BCG-treated PEC.

In a previous paper we have reported that antitumour activity of BCG-treated PEC was mediated by both direct cell-to-cell contact killing and cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α [20]. In fact, MBT-2 were susceptible to the killing activity of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 4). In the experiment using cell culture insert, the COX inhibitor seems to up-regulate both cytokines and cell-to-cell contact killing. However, killed BCG seem to induce only cell-to-cell contact killing in the presence or absence of a COX inhibitor, because killed BCG enhanced only small amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Therefore, the suppressive effect of PGE2 seems to be on cytokine production which enhances antitumour activity.

There are some reports that cancer cells produce PGE2 [23,24]. We also studied the effect of PGE2 and COX inhibitors on the growth of MBT-2 cells. We found that MBT-2 (1 × 105/ml) produced 1·9 nm of PGE2. However, the growth of MBT-2 was not influenced by 1 μm of a COX inhibitor and exogeneous addition of PGE2 (data not shown). Thus, the effect of PGE2 and COX inhibitors seemed to be on PEC, but not on tumour cells directly, in this report.

In conclusion, PGE2 produced by BCG-stimulated macrophages has a suppressive effect on macrophage-mediated cytotoxic activity and IFN-γ and TNF-α production, and COX inhibitors enhances these activities. Therefore, inhibitors of PG synthesis may be useful agents to reduce inflammatory responses and enhance BCG-immunotherapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kavoussi LR, Torrence RJ, Gillen DP, Hudson M, Haaff EO, Dresner SM, Ratliff TL, Catallona WJ. Results of 6 weekly intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin instillations on the treatment of superficial bladder tumors. J Urol. 1988;139:935–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42722-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Meijden APM. Nonspecific immunotherapy with Bacille Calmette–Guerin (BCG) Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123:179–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohle A, Nowc CH, Ulmer AJ, et al. Elevations of cytokines of interleukin-1, interleukin-2 and tumor necrosis factor in the urine of patients after intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy. J Urol. 1990;144:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohle A, Gerdes J, Ulmer AJ, Hofstetter AG, Flad HD. Effect of local Bacillus Calmette–Guérin therapy in patients with bladder carcinoma on immunocompetent cells of the bladder wall. J Urol. 1990;144:53–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zlotta AR, Drowart A, Huygen K, et al. Humoral response against heat shock proteins and other mycobacterial antigens after intravesical treatment with Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) in patients with superficial bladder cancer. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:157–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4141313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esuvaranathan K, Alexandroff AB, McIntyre M, et al. Interleukin-6 production by bladder tumors is upregulated by BCG immunotherapy. J Urol. 1995;154:572–5. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snijdewint FG, Kalinski P, Wierenga EA, Bos JD, Kapsenberg ML. Prostaglandin E2 differentially modulates cytokine secretion profiles of human T helper lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;150:5321–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chouaib S, Welte K, Mertelsmann R, Dupont B. Prostaglandin E2 acts at two distinct pathway of T lymphocyte activation: inhibition of interleukin 2 production and down-regulation of transferrin receptor expression. J Immunol. 1985;135:1172–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuroda E, Sugiura T, Zeki K, Yoshida Y, Yamashita U. Sensitivity difference to the suppressive effect of prostaglandin E2 among mouse strains: a possible mechanism to polarize Th2 type response in BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 2000;164:2386–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith WL, Garavito RM, DeWitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (cyclooxygenases) -1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33157–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ristimaki A, Garfinkel S, Wessendorf J, Maciag T, Hla T. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 by interleukin-1α1: evidence for post-transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1996;269:11769–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hempel SL, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. LPS induces prostaglandin H synthase-2 protein and mRNA in human alveolar macrophages and blood monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:391–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI116971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mickey DD, Mickey GH, Murphy WM, Niell HB, Soloway MS. In vitro characterization of four N-[4-(5-nitro-2-furyl) -2-thiazolyl] formamide (FANFT) induced mouse bladder tumors. J Urol. 1982;127:1233–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flick DA, Gifford GE. Comparison of in vitro cell cytotoxicity assays for tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol Meth. 1984;68:167–75. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zar JH. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; Biostatical analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vankataprasad N, Shiratsuchi H, Johnson JL, Ellner JJ. Induction of prostaglandin E2 by human monocytes infected with Mycobacterium avium complex: modulation of cytokine expression. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:806–11. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahr GM, Rook GAW, Stanford JL. Prostaglandin-dependent regulation of the in vitro proliferative response to mycobacterial antigens of peripheral blood lymphocytes from normal donors and from patients with tuberculosis or leprosy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;45:646–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomioka H, Saito H, Sato K. Characteristics of immunosuppressive macrophages induced in host spleen cells by Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:283–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denis M, Gregg EO. Modulation of Mycobacterium avium growth in murine macrophages: reversal of unresponsiveness to interferon-gamma by indomethacin or interleukin-4. J Leuko Biol. 1991;49:65–72. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada H, Matsumoto S, Matsumoto T, Yamada T, Yamashita U. Enhancing effect of an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis on BCG induced macrophage cytotoxicity against murine bladder cancer cell, MBT-2 in vitro. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:534–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarrios-Rodiles M, Chadee K. Novel regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 production by IFN-γ in human macrophages. J Immunol. 1988;161:2441–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Pouw Kraan TC, Boeije LC, Smeenk RJ, Wijdenes J, Aarden LA. Prostaglandin-E2 is a potent inhibitor of human interleukin 12 production. J Exp Med. 1995;181:775–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed SI, Knapp DW, Bostwick DG, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in human invasive transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5647–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitayama W, Denda A, Okajima E, Tsujiuchi T, Konishi Y. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 protein in rat urinary bladder tumors induced by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:2305–10. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2305. 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]