Abstract

The aetiology of chronic prostatitis is not understood. The aim of this study is to investigate an autoimmune hypothesis by looking for T cell proliferation in response to proteins of the seminal plasma. We studied peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation from 20 patients with chronic prostatitis and 20 aged-matched controls in response to serial dilutions of seminal plasma (SP) from themselves (autologous SP) and from a healthy individual without the disease (allo-SP). We found that the patients have a statistically greater lymphocyte proliferation to autologous SP at the 1/50 dilution on day 6 compared to controls (P=0·01). They also have a greater proliferation to allo-SP on both day 5 (P=0·001) and day 6 (P=0·01) at the same dilution. Using a stimulation index (SI) of 9 to either autologous SP or allo-SP on day 6 at the 1/50 dilution as a definition of a proliferative response to SP, then 13/20 patients as compared to 3/20 controls showed a proliferative response to SP (P=0·003, Fisher’s exact test). These data support an autoimmune hypothesis for chronic prostatitis.

Keywords: autoimmune, CPPS, prostatitis, seminal plasma

INTRODUCTION

Chronic abacterial prostatitis and prostatodynia (now referred to as CPPS types IIIa and IIIb, respectively, in the NIH classification [1]) are poorly understood conditions, which are insufficiently recognized [2]. They are surprisingly common and account for approximately 8% of visits to urologists in the United States. They affect men in all age groups but primarily those in the age group 36–50 years [3]. It has been documented that the impairment to quality of life from chronic prostatitis compares with that due to myocardial infarction, angina and Crohn’s disease [4].

Controversy exists concerning the aetiology of this condition. Current investigation has focused largely on a microbial or an autoimmune cause, though the two are not mutually exclusive. To investigate a microbial cause, investigators have used PCR to amplify microbial 16S rRNA genes from prostatic biopsies. Kreiger et al. demonstrated microbial 16S rRNA in 77% of the prostates of men with chronic prostatitis but did not investigate a control group [5]. A subsequent paper by Keay et al. found the 16S rRNA in the prostates of 8/9 men with prostate cancer (although this group had previously had trans-rectal biopsies) [6]. Hochreiter [7] found no 16S rRNA gene product in the stored prostates of 18 men whose prostates had been preserved at the time of organ donation and in whom there was no information on whether they had any prostatitis symptoms ante-mortem. In a subsequent study Kreiger found the 16S rRNA gene product in 20% of 107 patients with prostate cancer as compared to 46% of 170 men with chronic prostatitis. The median age of the men with prostate cancer was 64 and the median age of the men with prostatitis was 38 [8]. Essentially it is difficult to obtain aged matched controls to undergo a prostatic biopsy.

The autoimmune hypothesis suggests that types IIIa and IIIb prostatitis (CPPS) are caused by autoimmune mediated injury to the genital tract (including the prostate), which is precipitated by genitourinary inflammatory events such as urinary tract infection (UTI), acute bacterial prostatitis, urethritis and repetitive trauma. The male genital tract is an immune privileged site [9], and seminal plasma is highly immunosuppressive due to high concentrations of PGE2[10] in the semen. The seminal plasma is also capable of being recognized by the immune system. Halpern first described seminal plasma allergy in 1967 [11] in a woman who experienced postcoital anaphylaxis. Other authors have reported similar findings and suggested that the allergic component was a protein(s) in the range of 20–40 KD [12,13]. An antigen does not need to be produced by the prostate for the prostate to be affected as intraprostatic spermatozoa have been found on postmortem analysis [14] mainly in the peripheral zone.

The finding of increased levels of IgA and IgG in the expressed prostatic secretion of patients with abacterial prostatitis, compared to controls, supports an autoimmune aetiology for this condition, since this Ig was not specific for known microorganisms [15]. IgM deposition has also been demonstrated in the periglandular tissue of the prostate in 34/60 patients and 1/21 controls [16]. Alexander et al. noted CD4 positive T cell proliferation to a 1/100 dilution of pooled donor seminal plasma on day 5 in 3/10 men with prostatitis and 0/15 controls [17]. This group’s attempts to find the antigen recognized by CD4 T cells have hitherto been unsuccessful. They found no CD4 T-cell response to the purified prostatic proteins, β microseminoprotein and prostatic acid phosphatase, and while a stimulation index (SI) of 2 to prostate specific antigen (PSA) was recorded in 5/14 patients, this does not represent a substantial in vitro immune response [18]. A mouse model for chronic prostatitis suggests that it is possible to induce autoimmune inflammation in the lateral lobes of the prostate in a genetically susceptible mouse if a high enough dose of homogenized prostate is administered with adjuvant [19].

To test this autoimmune hypothesis we have measured lymphocyte proliferation to seminal plasma in patients with CPPS compared to healthy age-matched controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Local ethics committee approval was obtained prior to commencement of the study, and written informed consent was obtained from patients and controls. Patients were recruited from our Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome clinic with type IIIa/b prostatitis, duration of symptoms of at least 3 months, and a chronic prostatitis symptom index score (CPSI) [20] of at least 12 at the start of the study. They underwent the following assessment: history with CPSI and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), a physical examination, 24-h frequency voided urine volume chart, urinary flow rate and residual volume estimation, 4 Glass Stamey localization [21], semen analysis (to determine the classification under the 1995 NIH guidelines) and trans-rectal ultrasound. If interstitial cystitis was suspected cystoscopy was also performed. Controls were recruited by poster and were excluded from study if they had a CPSI pain score of >0, an IPSS of >7, or previous symptoms suggestive of chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS). They underwent the same assessment as the patients but did not have a Stamey localization. Both groups abstained from NSAIDs or steroid use for 4 weeks prior to and during the study.

Seminal plasma (SP)

Semen was obtained from the patient or control directly into a sterile container and is referred to as autologous seminal plasma (SP). The semen was obtained at the same visit as blood for proliferation assays. Semen was obtained from a single healthy individual with a total CPSI score of 1 and is referred to as allo-SP. The semen was allowed to liquefy for 30 min and was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min to remove spermatozoa and white cells. The supernant (SP) was collected, diluted in tissue culture medium, RPMI 1640 (Gibco), and filtered through a 0·2-μm filter to exclude bacteria. SP was used in culture at a final dilution of 1/25 doubling to 1/200 for the proliferation assays, as our early experiments suggested that the balance between in-vitro inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation (see below) and stimulation was fine and that optimum stimulation was within this range.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

Blood was taken at a second visit and collected to heparinized tube (100 μ/50 ml) and diluted 1:1 in PBS. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMCs) were obtained by Ficoll (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB) gradient centrifugation of whole blood. The cells were washed three times in PBS (Oxoid plc) before being resuspended in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10 mm Hepes buffer, pyruvate, non-essential amino acids, 2 mml-glutamine, 100 iμ/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Proliferation assays

Assays were performed using 200 μl 96 U-well plates, with the antigens in triplicate in the presence of 5% AB serum. PBMC were used at final concentration of 1 × 105 per well. Antigens and PBMC were incubated at 37°C in 5·2% CO2. Control wells were used with PBMC and no antigen. Standard antigens were also used: tuberculin protein (PPD) (Evans) at 1000 μ/ml (as a measure of a response to a recall antigen) and keyhole lymphocyte haemocyanin (KLH) (Calbiochem) at 100 μg/ml (as a measure of a primary in-vitro response to antigen). PBMC proliferation was measured by incorporation of 1 μCi/well methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB) during the last 18 h of culture. Results are expressed as counts/min (cpm). As our early experiments suggested that SP can delay an in-vitro immune response, PBMC proliferation was measured after 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 days incubation with autologous SP or allo SP at doubling dilutions of 1/25–1/200. An SI was calculated by dividing the mean cpm from the triplicate wells containing antigen by the mean cpm obtained from the control wells. Statistical analysis was performed using the t-test assuming unequal variance (two-tailed), and Fisher’s exact test.

The phenotype of cells in cultures responding to SP was determined by staining with antibodies to CD3 (Dako), CD4 (Dako), CD8 (Dako), TCRαβ (Becton Dickinson), TCRγδ (Pharmingen) and CD25 (Dako), and analysed by two-colour flow cytometry to identify those cells expressing CD25 as a marker of activation.

Measurement of SP immunosuppression

Phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), a non-specific T cell mitogen, was used at 1 μg/ml to measure inhibitory effects of SP on T cell proliferation. Autologous PBMC and SP were prepared as above. SP was used at doubling dilutions of 1/25–1/12,800, and PHA was added to the SP. 3H]thymidine incorporation was measured after 3 days. The SI obtained for PHA and for PHA plus SP were used to calculate percentage inhibition of the PHA response.

RESULTS

Patients and controls

We studied 20 patients and 20 age-matched controls. Table 1 shows that the groups were successfully age-matched. It also demonstrates that the patients have a significantly greater incidence of past inflammation of the genito-urinary tract defined as proven UTI, urethritis or trauma causing a scrotal haematoma than controls, and also a higher incidence of eczema and asthma.

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients and controls

| Patients mean (range) | Controls mean (range) | P-value (Fisher’s exact) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41 (25–67) | 39 (22–59) | n.s. |

| GU inflammation/trauma | 17 | 3 | <0·0001 |

| No. of GU events | 5 (1–18) | 1 (1–1) | |

| Vasectomy | 5 | 5 | n.s. |

| Asthma/eczema | 7 | 1 | 0·04 |

| CPSI score | 25 (12–43) | 1 (0–4) | |

| IPSS score | 18 (4–33) | 2 (0–5) | |

| Semen WCC/106/ml | 4·2 (0·5–28·8) | 2·5 (0·9–5·9) | n.s |

| NIH classification | IIIa n = 18 | ||

| IIIb n = 2 |

Seminal plasma inhibition of T cell response

Seminal plasma substantially inhibited T cell proliferation. Table 2 compares the mean percentage response to PHA at each SP dilution on day 3. This demonstrates no significant difference in the inhibitory effects of seminal plasma obtained from patients and controls.

Table 2.

The inhibitory effects of different dilutions of SP on PBMC proliferative responses to PHA measured and the results expressed as percentage of the c.p.m obtained in the absence of SP

| SP dilution | Patients | Controls | P-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/25 | 5·4 | 3·0 | 0·12 |

| 1/50 | 13·5 | 10·3 | 0·31 |

| 1/100 | 23·3 | 20·3 | 0·4 |

| 1/200 | 33·0 | 31·4 | 0·73 |

| 1/400 | 42·5 | 42·5 | 1·0 |

| 1/800 | 54·3 | 55·8 | 0·82 |

| 1/1600 | 65·9 | 66·5 | 0·93 |

| 1/3200 | 77·6 | 76·6 | 0·88 |

| 1/6400 | 84·0 | 80·0 | 0·56 |

| 1/12800 | 85·9 | 85·4 | 0·95 |

PBMC proliferation to autologous and allo-SP

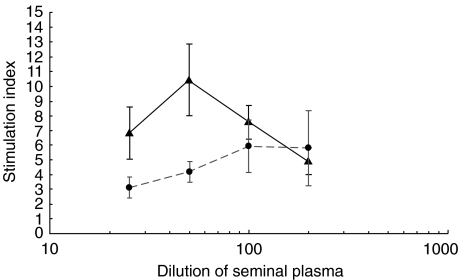

Despite the inhibition of the response to PHA seen at dilutions of 1/50, we demonstrated significant proliferation of lymphocytes from the patients in response to seminal plasma, which was less marked in controls. Table 3 demonstrates the difference in proliferation in response to SP which, as Fig. 1 shows, occurred in a dose-dependent manner. To illustrate the increased responsiveness of patient PBMC as compared to controls the proportions of each group achieving different levels of SI were examined. It was found that 13/20 patients compared to 3/20 controls achieved an SI of > 9 to either autologous SP or allo-SP on day 6, P=0·003, Fisher’s exact test. We have termed this as a proliferative response to SP.

Table 3.

Proliferative responses of PBMC from patients and controls to autologous and allo SP at a 1/50 dilution on the days shown. Results expressed as SI

| SP | Day | Dilution | Patient SI (range) | Control SI (range) | P-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| autologous | 6 | 1:50 | 10·4 | 4·0 | 0·01 |

| (0·1–36·6) | (0·1–10·4) | ||||

| allo-SP | 5 | 1:50 | 9·9 | 1·9 | 0·001 |

| (0·2–30·0) | (0·1–9·4) | ||||

| allo-SP | 6 | 1:50 | 12·9 | 2·8 | 0·01 |

| (0·2–74·0) | (0·01–16·1) |

Fig. 1.

Mean proliferative responses of PBMC from 20 patients and 20 controls to different concentrations of autologous SP (1/25–1/200). Results are expressed as SI (±s.e.m.) on day 6. ▴, Patients; •, controls.

The phenotype of the cells present in responding cultures was examined by flow cytometry. The percentage of CD4+ T cells which had been stimulated with SP and expressed CD25 was 7·1% (±1·8, n = 6), whereas only 2·9% (±1) of the CD8+ T cells which had been stimulated with SP expressed CD25. The corresponding values for cells cultured in medium were 4·6% (±1·2%) for CD4+ T cells and 1·2% (±1·0) for CD8+ cells; these results are consistent with the idea that proliferation is principally mediated by CD4 positive T cells. The activated cells were also shown to express TCRαβ rather than TCRγδ. Definitive determination of the responding cell type awaits further evaluation of the responses of purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Responses to PPD and KLH

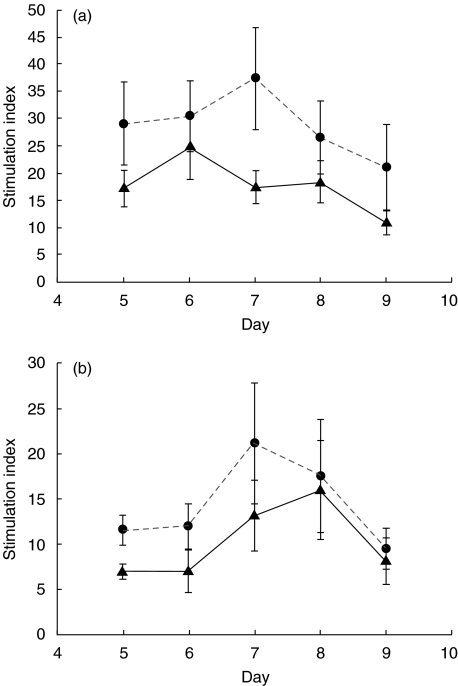

The patients’ increased response to SP is not caused by greater in-vitro responses to antigens in general, as the patients actually showed reduced PBMC proliferation to a recall antigen, PPD, and to a novel antigen, KLH (see Fig. 2a,b.)

Fig. 2.

Proliferative responses of PBMC from patients and controls to the antigens 1000 units/ml PPD (a) and 100 μg/ml KLH (b). Results are expressed as the mean SI on days 5–9 of culture. ▴, Patients; •, controls.

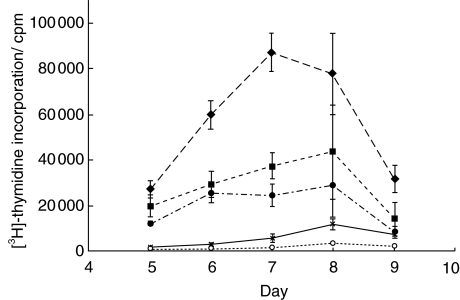

Prostasomes and PBMC proliferation

The antigen(s) causing the proliferative response to SP does not appear to be present in prostasomes (see Fig. 3). In this experiment the SP from a responder was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min, the supernatant further centrifuged at 10 000 g for 15 min and the supernatant collected and further centrifuged at 100 000 g to precipitate prostasomes [22], which were re-suspended in medium. The patient’s response to autologous SP was similar to the response to 100 000 g supernatant. The proliferation to his preparation of prostasomes was not significantly above background.

Fig. 3.

Proliferative responses of PBMC from an individual patient to unfractionated autologous and allogeneic SP, and to fractions of autologous SP produced by ultracentrifugation (i.e. prostasomes and supernatant). Results are expressed as 3H]-thymidine incorporation mean c.p.m. (±s.e.m.). ○, Control: no antigen; ▪, autologous SP 1/50; ♦, allo-SP 1/50; •, autologous SP 100 000g supernatant; ×, autologous prostasomes 1/12·5.

DISCUSSION

As far as we are aware, this is the first report of a study of immune responses in chronic prostatitis, which has selected a control group using the newly developed NIH CPSI. There were 10 men who presented for this study as controls, who could not be recruited as they scored above 0 on the pain domain of the CPSI, or who were moderately symptomatic on the IPSS. This is an important consideration in selecting a control group, given that prostatitis-like symptoms in men are relatively common.

The inhibitory effects of SP have not previously been measured in men with CPPS. From this investigation, we conclude that the patients’ PBMC proliferation in response to autologous SP therefore does not reflect a reduction in immunosuppressive factors. This study also provides indirect evidence that the seminal vesicles are unaffected by the disease process (see below).

The presence of spermatozoa in the normal prostate demonstrates semen–prostatic reflux. This semen–prostatic reflux is likely to occur in many more men than the 9/100 that Nelson [14] demonstrated in his post-mortem study, as not all the men were likely to be sexually active before their deaths. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the immunosuppressive factors of the seminal plasma reflux into the prostate. In the healthy prostate these factors probably have little effect, although they may render this organ an immune privileged site. If, however, an autoimmune process is occurring in the prostate in CPPS, these factors may actually have a positive impact upon the disease process, especially the prostaglandins produced by the seminal vesicles [23]. Treatment of patients with NSAIDs, which lower semen prostaglandin levels [24], may therefore have a negative impact on CPPS. This may explain why Rofecoxib has minimal benefit in this group of patients [25].

We found that a greater percentage of our patients had a proliferative response to SP 13/20 (65%) than did Alexander et al., who noted 3/10 (30%) [17]. This suggests that an autoimmune process affecting these men may be more common than thought previously. We also found no statistically significant difference in PBMC proliferation to either autologous SP or allo-SP at 1/100 (data not shown), the dilution that Alexander used to compare his groups. We believe that the differences in detecting a proliferative response to SP in our study, compared to that of Alexander, was due to our examination of a range of SP dilutions and time-points. We have found, using autologous SP and allo-SP, that 1/50 is the optimum dilution for observing PBMC proliferation in patients, with the optimum day being day 6. Alexander et al. measured CD4 T cell proliferative responses to pooled donor SP at 1:100 dilution on day 5 in their study. There were further differences in Alexander’s methods, other than the dilution, source of SP and the time-point measured, which may account for some of the differences in detection of lymphocyte proliferation. Alexander used antigen-presenting cells (APC) and immunoaffinity purified CD4+ T cells, while we used PBMC. This may be relevant, as a recently published study has found that the ratio of CD8+/CD4+ T cells found on prostatic biopsy was increased in pathological inflammation in a group of category IIIb prostatitis patients [26]. While it is possible that CD8+ T cells proliferated from the PBMC we used, this in itself is unlikely to account for the differences detected. Finally, Alexander et al. compared their 10 patients and 15 normal men by defining a specific recall proliferative response to SP as a ‘cutoff point of 3 standard deviations above the mean CPM for unpulsed autologous PBMC’ rather than calculating stimulation indices: this is unlikely to have affected the detection rate. Our study did, however, confirm Alexander’s findings that seminal plasma is capable of elicting lymphocyte responses in men with chronic prostatitis.

Controversy exists concerning the incidence of histological inflammation of the prostate in patients with CPPS. We have studied the immune responses to seminal plasma, so any antigen(s) implicated may be produced anywhere along the genital tract. Two large biopsy studies have studied prostatic histological inflammation in patients with chronic prostatitis. True and coworkers [27] found prostatic inflammation in only 33% of patients with 29% having mild inflammation and 4% moderate inflammation. This group examined 124 biopsies taken from 97 men. Their biopsy technique used finger-guided 18G needle biopsies, one from each lobe of the prostate. Using this method it was unlikely that the peripheral zone of the prostate was sampled. Doble et al.[16] used trans-rectal ultrasound-guided, trans-perineal biopsy, with a 14G needle, to sample the area of abnormality, which was usually in the peripheral zone. Using this technique they found that 88% of the 60 men examined had histological inflammation. Both Kreiger’s [26] and Doble’s [16] group found that the inflammation was located primarily in the periglandular and stromal tissue. It is likely that the different biopsy techniques explain the varying incidence of histological inflammation in these two papers, as one or two biopsies would, by current standards, seem an inadequate method for sampling the prostate [28]. Weidner [29] found that seminal plasma PSA is normal in men with chronic prostatitis, suggesting that the glandular PSA secreting cells of the prostate are unaffected by CPPS.

Our data support the hypothesis that immune recognition of SP is a feature of CPPS. This immune recognition may be responsible for continuing autoimmune mediated injury to the genital tract, which results in a persistent inflammatory reaction after an eliciting event has subsided. The inciting antigen is present in the SP of healthy individuals who may also have T lymphocytes potentially able to react to SP. However, it requires sensitization from an inflammatory ‘event’ to prime T cell responses to SP and produce chronic autoimmune prostatitis.

In recent experiments we have purified SP by gel filtration and have noted responses to a high molecular weight (HMW) antigen. We are in the process of characterizing this HMW antigen, and testing our original cohort of patients and controls with a purified preparation of this protein.

The identification and characterization of the antigen should help to resolve some of the controversy concerning the pathogenesis of chronic prostatitis and result in diagnostic tests. Strategies aimed at modulating immune responses to this antigen (possibly by desensitization) may be useful therapeutically.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Addenbrooke’s Hospital Charities Committee and Prostate Research Campaign UK for financial support; Dr Joyce Young for flow cytometry on responding cells; and Dr Brian Toms, Cambridge University Department of Public Medicine for statistical advice.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Workshop on Chronic Prostatitis: Summary Statement. Bethseda, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. December. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MM, O’Leary MP, Barry MJ. Prevalence of bothersome genitourinary symptoms and diagnoses in younger men on routine primary care visits. Urology. 1998;52:422–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins MM, Stafford RS, O’Leary MP, Barry MJ. How common is prostatitis? A national survey of physician visits. J Urol. 1998;159:1224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenniger K, Heiman JR, Rothman I, Berghuis JP, Berger RE. Sickness impact of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and its correlates. J Urol. 1996;155:965–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krieger JN, Riley DE, Roberts MC, Berger RE. Prokaryotic DNA sequences in patients with chronic idiopathic prostatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3120–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3120-3128.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keay S, Zhang CO, Baldwin BR, Alexander RB. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of bacterial 16s rRNA genes in prostate biopsies of men without chronic prostatitis. Urology. 1999;53:487–91. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochreiter WW, Duncan JL, Schaeffer AJ. Evaluation of the bacterial flora of the prostate using a 16s rRNA gene based polymerase chain reaction. J Urol. 2000;163:127–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreiger JN, Riley DE, Vessella RL, Miner DC, Ross SO, Lange PH. Bacterial in DNA sequences in prostate tissue from patients with prostate cancer and chronic prostatitis. J Urol. 2000;164:1221–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollanen P, Cooper TG. Immunology of the testicular excurrent ducts. J Reprod Immunol. 1994;26:167–216. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quayle AJ, Kelly RW, Hargreave TB, James K. Immunosuppression by seminal prostaglandins. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75:387–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halpern BN, Ky T, Robert B. Clinical and immunological study of an exceptional case of reaginic type sensitization to human seminal fluid. Immunology. 1967;12:247–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blair H, Parish WE. Asthma and urticaria induced by seminal plasma in a woman with IgE antibody and T-lymphocyte responsiveness to a seminal plasma antigen. Clin Allergy. 1985;15:117–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1985.tb02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein JA, Herd ZA, Bernstein DI, Korbee L, Bernstein L. Evaluation and treatment of localized vaginal immunoglobulin E-mediated hypersensitivity to human seminal plasma. Obset Gynaecol. 1993;82:667–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson G, Culberson DE, Gardner WA. Intraprostatic spermatozoa. Human Pathol. 1988;19:541. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shortcliffe LMD, Wehner N. The characterization of bacterial and nonbacterial prostatitis by prostatic immunologlobulins. Medicine. 1986;65:399–414. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doble A, Walker MM, Harris JRW, Taylor-Robinson D, Withrow RON. Intraprostatic antibody deposition in chronic abacterial prostatitis. BJU. 1990;65:598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1990.tb14827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander RB, Brady F, Ponniah S. Autoimmune prostatitis. evidence of T cell reactivity with normal prostatic proteins. Urology. 1997;50:893–9. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00456-1. 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponniah S, Arah I, Alexander RB. PSA is a candidate self-antigen in Autoimmune chronic prostatitis/CPPS. Prostate. 2000;44:49–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000615)44:1<49::aid-pros7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keetch DW, Humphrey P, Ratliff TL. Development of a mouse model for nonbacterial prostatitis. J Urol. 1994;152:247–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32871-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, et al. The National institutes of health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. J Urol. 1999;162:369–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meares EM, Stamey TA. Bacteriologic localization patterns in bacterial prostatitis and urethritis. Invest Urol. 1968;5:492–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly RW, Holland P, Skibinski G, et al. Extracellular organelles (prostatsomes) are immunosuppressive components of the human semen. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;86:550–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb02968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benvold E, Gottlieb C, Svanborg K, et al. Absence of prostaglandins in semen of men with cystic fibrosis is and indication of the contribution of the seminal vesicles. J Reprod Fertil. 1986;78:311–4. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0780311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bendvold E, Gottlieb C, Svanborg K, Bydeman M, Eneroth P, Cai QH. The effects of naproxen on the concentration of prostaglandins in human seminal fluid. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:922–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48623-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nickel JC, Gittleman M, Malek G, et al. Effects of Rofecoxib in patients with chronic nonbacterial prostatitis: a placebo controlled pilot study. J Urol. 2001;165(Suppl. 5):27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubert J, Barghorn A, Funke G, et al. Noninflammatory chronic pelvic pain syndrome: immunological study in blood, ejaculate and prostate tissue. Eur Urol. 2001;39:72–8. doi: 10.1159/000052415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.True LD, Berger RE, Rothman I, Ross SO, Kreiger JN. Prostate Histopathology and the chronic prostatitis/Chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective biopsy study. J Urol. 1999;162:2014–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babaian RJ, Toi A, Kamoi K, et al. A comparative analysis of sextant and an extended 11-core multisite directed biopsy strategy. J Urol. 2000;163:152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig M, Kummel C, Schroeder-Printzen I, Ringert RH, Weidner W. Evaluation of seminal plasma parameters in patients with chronic prostatitis or leukocytospermia. Andrologia. 1998;30(Suppl. 1):41–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1998.tb02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]