Abstract

To analyse the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) on T-lymphocyte functions we selected seven HIV-1 perinatally infected children (CDC immunological category 1 or 2) who had neither a fall in their plasma HIV-1 RNA levels nor a significant rise in CD4+ lymphocyte counts while receiving HAART. Clinical signs and symptoms were monitored monthly. Plasma viral load, CD4+, CD8+, CD19+ lymphocyte counts and in vitro T-lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens (anti-CD3, phytohaemoagglutinin, concanavalin A and pokeweed mitogen) and recall antigens (Candida albicans and tetanus toxoid) were tested at baseline and after 1, 3, 6 and 12 months of HAART. Twenty-two healthy age-matched children were studied as controls. A gain in body weight, no worsening of the disease and no recurrence of opportunistic infections were observed. At baseline, the majority of the children had low responses to mitogens, and all of them had a defective in vitro antigen-specific T-lymphocyte response (<2 standard deviations below the mean result for controls). During HAART, a significant increase in the response to mitogens and antigens was observed in all the patients. The T-lymphocyte response was restored more consistently against antigens to which the immune system is constantly exposed (Candida albicans, baseline versus 12 months: P < 0·001) compared with a low-exposure antigen (tetanus toxoid, baseline versus 12 months: P < 0·01). HAART restores in vitro T-lymphocyte responses even in the absence of a significant viral load decrease and despite any significant increase in CD4+ lymphocyte counts. It implies that a direct mechanism might be involved in the overall immune recovery under HAART.

Keywords: children, HAART, HIV, T-cell function

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 infection leads to a severe depletion of CD4+ T- lymphocytes in adults and children [1]. This decrease is associated with a progressive impairment of immune function. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, including at least 1 protease inhibitor PI]), allows for a significant decrease in plasma and tissue HIV-1 RNA load, as well as a quantitative recovery of peripheral CD4+ T-lymphocytes in the majority of adults with HIV-1 infection [2–5] resulting in a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality [6]. However, the mechanisms governing immune improvement under HAART are still controversial.

HIV-infected children demonstrate an expanded capacity for T-lymphocyte reconstitution because of the greater potential for regeneration by the paediatric thymus [7,8] and, in contrast to adults, the expression of CD45RA and CD62L (phenotypic markers of thymic derived naive T-lymphocytes) is very high [9,10].

Although children have higher viral burdens than adults, which would predict more rapid disease progression and a poorer prognosis [11], they exhibit a higher degree of responsiveness to therapy in terms of CD4+ T-lymphocyte reconstitution when compared with adults [12]. These findings suggest that the dynamics of immunoreconstitution is different in children.

We have recently reported a dissociated response to HAART in a group of HIV-1 infected children, with a recovery of CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte counts despite virological failure [13].

In this study we examined the effect of 12 months of HAART on in vitro T-lymphocyte responses to aspecific and specific immune stimuli in a group of HIV-1 infected children who had neither a fall in plasma HIV-1 RNA levels nor a significant rise in CD4+ lymphocytes while receiving therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Seven HIV-1 perinatally infected children (two males and five females aged 10·4 years median; range 7·1–14·10]) classified as immunological category 1 or 2 according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention criteria [14], were selected from a larger group of children enrolled in a prospective study aimed at investigating the effect of switching from a double combination antiretroviral therapy with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) to HAART.

The criteria of selection were: (1) all children were treatment-experienced but protease inhibitor-naive; (2) absence of a significant virological response (decrease in viral load <1·0 log10 ml–1) during 12 months of therapy; and (3) CD4+ count >200 cells/μl, at baseline. No concomitant active opportunistic infections were present at enrolment. Clinical signs and symptoms, HIV-related and AIDS-defining events were monitored monthly.

The switch of treatment to HAART was performed in accordance with the criteria of the Italian guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in children with perinatal HIV-1 infection [15]. Drugs used in the double NRTI combination therapy included didanosine (180 mg/m2/day), lamivudine (8 mg/kg/day), stavudine (2 mg/ kg/day) and zidovudine (480 mg/m2/day). HAART included two new NRTI (or one new NRTI and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors nevirapine, 200 mg/m2/day]), and one protease inhibitor (nelfinavir90 mg/m2/day]).

Blood was taken during routine examination after the parents’ informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Hospital’s Ethic Committee.

Control group

To acquire reference values, 22 healthy children (eight males and 14 females aged 10·1 years median; range 6·5–14·6]) were studied. They were selected from children hospitalized for minor elective surgery. The criteria for inclusion in the control group was that the child had no known immune disease, was HIV-1 seronegative and free from infections and medication for at least 1 month before the blood sample. Blood samples were taken during routine examinations after the parents’ informed consent had been obtained.

Measurement of HIV-1 RNA

Plasma HIV-1 RNA load was quantified by quantitative HIV reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Amplicor HIV Monitor test, Hoffmann LaRoche Diagnostic System, Inc., Branchburg, NJ, USA), with a limit of detection of approximately 200 copies/ml. Results were expressed as log10 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml.

Lymphocyte phenotyping

Phenotyping of CD3+CD4+CD45+ and CD3+CD8+CD45+ T- lymphocyte subsets were performed on fresh EDTA-blood samples by three-colour flow cytometry using a whole blood staining technique as described previously [16]. Peripheral blood was stained with PerCP-conjugated CD45, phycoeritrin-conjugated CD3 and fluorescent isothiocyanate-conjugated CD4 or CD8 monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Analysis was performed on a three-colour multiparameter flow cytometer (FACScan, Becton Dickinson) using Lysis II software. Absolute CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts were calculated on the basis of absolute lymphocyte counts.

Lymphocyte proliferative assay

Mitogen-induced lymphoproliferative responses. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), obtained from whole blood and purified using Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation, were plated at 2 × 105 cells/well into 96-well plates in RPMI-1640 with 5% fetal calf serum. Anti-CD3 MoAb (OKT3), phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), concanavalin A (ConA) and pokeweed mitogen (PWM) at a final concentration of 25 ng/ml, 10 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml and 20 μg/ml, respectively, were added. Cultures were set up in triplicate. The control wells consisted of three replicates with no mitogen. On the second day of culture, 0·25 mCi 3H]-thymidine (Thy) was added to each well. The cells were harvested on the third day and counts per minute (cpm)/well were determined. Stimulation indices were calculated as cpm in culture with mitogen divided by cpm in culture without mitogen.

Antigen-specific lymphoproliferative responses. Cultures were set up essentially as described previously for mitogen cultures with the following differences: separated PBMC were plated in RPMI 1640 with 5% human AB serum, the control wells consisted of three replicates with no antigen, the addition of 0·25 mCi 3H]-Thy/well was on the fifth day of culture and the cells were harvested on the sixth day. To test proliferative response to recall antigens Candida albicans (heat killed bodies) and tetanus toxoid (TT) were added to the cultures at a concentration of 2 × 106 bodies/ml and 5 ng/ml, respectively. Stimulation indices were calculated as cpm in culture stimulated with antigen divided by cpm in unstimulated culture.

Definitions and statistical analysis

The decrease in viral load was considered significant if the reduction was >1·0 log10 ml−1 after 8–12 weeks of HAART. A significant decrease in CD4+ lymphocyte numbers was defined as a loss of 10 centiles over a period of 3 months. A loss of CD4+ lymphocytes lower than those values was considered as a stabilization in their level.

Baseline and follow-up data of patients receiving HAART were compared by the Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test. A one-way analysis of variance for repeated measures was carried out to compare single times. Differences were considered significant at P < 0·05.

RESULTS

Clinical evaluation

All patients reached the 12th month of follow-up. Before entry, the antiretroviral therapy consisted of two NRTI (zidovudine + lamivudine) in all seven children. The HAART regimen included one protease inhibitor (nelfinavir) plus two new NRTI (didanosine + stavudine) in six patients or one new NRTI plus a NNRTI (stavudine + nevirapine) in one patient.

At baseline the children were disease stage N2 (1/7), A1 (3/7), B2 (2/7) and C2 (1/7). All of them experienced a gain in body weight from baseline in the first 6 months of therapy (mean increase 2·6 ± 0·5 kg). Constitutional symptoms, when present, resolved shortly after starting HAART. The patient who was disease stage C2 had no recurrences of opportunistic infections. In the other six patients no worsening of clinical class occurred.

Changes in viral load and lymphocyte subsets

Table 1 shows the changes in viral load and in CD4+, CD8+ and CD19+ lymphocyte counts during the 12 months of HAART. Considering the viral load, no patients showed a significant reduction. One child had an increase of 0·5 log10 ml–1 HIV-RNA copies/ml. In general, the trend for CD4+, CD8+ and CD19+ lymphocytes was a stabilization in their numbers during the 12 months of HAART. In fact, no significant changes were observed in all lymphocyte subsets studied when comparing the baseline with the later time point values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in viral load and in CD4+, CD8+ and CD19− lymphocytes in the seven HIV-1+ children

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-RNA | |||||||

| log10 copies/ml | |||||||

| Baseline | 3·51 | 4·11 | 2·92 | 5·11 | 4·9 | 4·8 | 4·58 |

| 1 month | 3·14 | 3·2 | 2·94 | 4·28 | 3·35 | 4·9 | 2 |

| 3 months | 2·95 | 4·05 | 2·27 | 4·33 | 2·94 | 5·08 | 3·21 |

| 6 months | 2·69 | 4·64 | 2·27 | 4·8 | 4·03 | 4·96 | 4·3 |

| 12 months | 2·95 | 3·61 | 2·54 | 4·3 | 4·3 | 5·31 | 3·9 |

| CD4+ cells/ml (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 468 (29) | 816 (42) | 450 (15) | 342 (17) | 630 (37) | 997 (37) | 210 (18) |

| 1 month | 523 (30) | 725 (39) | 405 (15) | 447 (13) | 771 (30) | 1286 (26) | 241 (24) |

| 3 months | 768 (33) | 668 (35) | 365 (15) | 663 (18) | 95 (32) | 1267 (32) | 200 (23) |

| 6 months | 685 (29) | 826 (34) | 360 (15) | 388 (16) | 543 (27) | 1547 (38) | 342 (17) |

| 12 months | 596 (25) | 727 (38) | 450 (18) | 420 (18) | 626 (32) | 1558 (38) | 342 (17) |

| CD8+ cells/ml (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 775 (48) | 796 (41) | 1230 (41) | 844 (42) | 749 (44) | 862 (32) | 467 (40) |

| 1 month | 895 (39) | 651 (35) | 1050 (40) | 2510 (73) | 925 (36) | 2472 (50) | 533 (53) |

| 3 months | 1280 (55) | 668 (35) | 993 (41) | 2580 (70) | 825 (38) | 1742 (44) | 365 (42) |

| 6 months | 1282 (50) | 850 (35) | 984 (41) | 1576 (65) | 765 (38) | 1588 (39) | 460 (36) |

| 12 months | 1210 (46) | 688 (36) | 775 (31) | 1519 (65) | 844 (43) | 1722 (42) | 531 (41) |

| CD19+ cells/ml (%) | |||||||

| Baseline | 145 (9) | 117 (6) | 420 (14) | n.t. | 204 (12) | 162 (6) | 187 (16) |

| 1 month | 157 (8) | 186 (10) | 420 (15) | 69 (2) | 540 (21) | 544 (11) | 60 (6) |

| 3 months | 163 (7) | 267 (14) | 399 (14) | 147 (4) | 413 (19) | 396 (10) | 130 (15) |

| 6 months | 236 (10) | 316 (13) | 327 (12) | 170 (7) | 483 (24) | 448 (11) | 243 (19) |

| 12 months | 238 (10) | 218 (11) | 400 (16) | 164 (7) | 333 (17) | 451 (11) | 259 (20) |

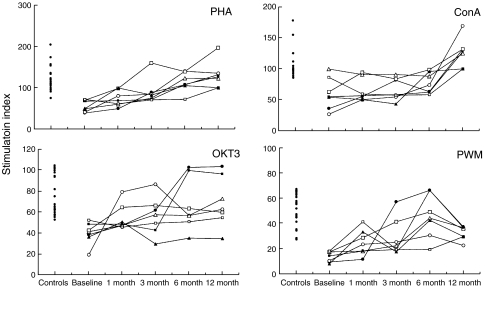

Lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens

At baseline, the majority of the children had low responses to mitogens as compared with the HIV-1 negative controls (Fig. 1). The in vitro response was <2 standard deviation (s.d.) below the mean result of controls in 7/7, 4/7, 3/7 and 2/7 patients for PWM, PHA, anti-CD3 and ConA, respectively. However, with the exception of two children who showed a response to ConA comparable to the lower response range of the controls, the remaining patients displayed a response <1 s.d. below the mean of controls for all the tested mitogens. Thus, a high proportion of patients with CD4 counts >200 cells/μl had dysfunctional CD4+ T-lymphocytes.

Fig. 1.

Time-course of the lymphocyte proliferative response in the presence of the indicated mitogens in the seven HIV-1 infected children enrolled in the study. Each symbol represents a single patient. Data are expressed as stimulation index (cpm in culture with mitogen divided by cpm in culture without mitogen). Time is reported in the x-axis. The lymphocyte proliferative response of 22 healthy controls is reported on the left side of each graph.

During the 12 months of HAART, a significant increase in the response to all the mitogens tested was observed. The recovery of the PHA-response was significant after 3 months of therapy and raised at the following time points (0 versus 3 months: P < 0·01; 0 versus 6 or 12 months, P < 0·001). The increase in the responses to anti-CD3 and PWM was slower and became significant only after 6 months (0 versus 6 or 12 months: P < 0·05). Twelve months was necessary to obtain a significant increase in the response to Con A (0 versus 12 months: P < 0·001).

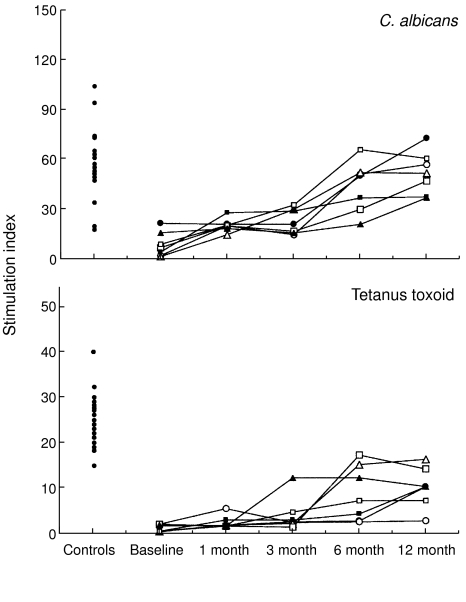

Lymphocyte proliferative responses to antigens

All seven children had a defective in vitro antigen-specific T- lymphocyte response at baseline (Fig. 2). In particular, the response to C. albicans was <2 s.d. below the mean result of the controls in six of seven cases and <1 s.d. in the last child. On the other hand, seven of seven cases had a response to tetanus toxoid markedly lower than 2 s.d. below the mean result of the controls.

Fig. 2.

Time-course of the lymphocyte proliferative response in the presence of the indicated antigens in the seven HIV-1 infected children enrolled in the study. Each symbol represents a single patient. Data are expressed as stimulation index (cpm in culture with antigen divided by cpm in culture without antigen). Time is reported in the x-axis. The lymphocyte proliferative response of 22 healthy controls is reported on the left side of each graph.

These responses increased significantly during HAART and the level of recovery was antigen-dependent. The rise in the Candida-specific T-lymphocyte response started very early, becoming significant at just 1 month (0 versus 1 and versus 3 months: P < 0·05; 0 versus 6 or 12 months: P < 0·001). The increase in the tetanus-specific T-lymphocyte response was slower but sustained over time (0 versus 6 and versus 12 months: P < 0·01).

DISCUSSION

The in vitro T-lymphocyte response is restored in adults [17] and children [18] following fully successful antiretroviral therapy. Several reports suggest that under HAART some HIV-infected adults and children can have significant increases in CD4+ lymphocyte counts despite incomplete virus suppression or even virological failure [19–23].

In a recent study Chougnet et al.[24] observed that in a group of HIV-1 infected children treated with HAART for >2 years there was a marked increase in the proliferative response and skin reactivity to recall antigen. However, this improvement was associated with a decrease in viral load and an increase in CD4+ T- lymphocyte numbers. Similarly, over 24 weeks in HIV-1 infected children, HAART increased CD4+ cell counts and decreased viral loads, in addition to inducing a strong rise in both the DTH response to C. albicans and the production of IL-12p70 by monocytes [25]. In contrast, no significant increase in the lymphoproliferative response to recall antigens was noted by Borkowsky et al.[26] in HIV-1 infected children after 44 and 48 weeks of HAART, despite the increase in CD4+ T-lymphocytes, perhaps reflecting the fact that baseline immune function was relatively intact in this population.

This study demonstrates for the first time that, under HAART, there is a restoration of mitogen and antigen-specific T-lymphocyte responses in vitro despite a virological failure and even in the absence of a significant increase in CD4+ lymphocyte counts. These results support the hypothesis that the immunological benefits of HAART derive from mechanisms other than just the antiretroviral activity [13,27,28].

HAART has significantly reduced morbidity rates in HIV-1 positive patients [6,29]. Many patients experienced both virological and immunological responses to HAART in terms of reduced levels of plasma HIV-1 RNA as well as increased levels of CD4+ T-lymphocytes [2,30]. Between 7% and 15% of HAART adult patients, however, have a seemingly paradoxical response to HAART in that their CD4+ lymphocytes levels increase substantially but their levels of plasma HIV-1 RNA remain high [23,31,32]. Although virological responders have a better clinical outcome than virological non-responders, the probability of clinical progression is low even in the latter group [33]. HAART is highly effective in reducing the mortality of perinatally infected children [34] despite the fact that the proportion of virological failure is high [19]. The present study has evaluated the in vitro T-lymphocyte function in children with virological failure of HAART.

In a previous study carried out in perinatally HIV-1 infected children we demonstrated that both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte numbers might raise despite virological failure [13]. In this report, we selected seven patients that had neither a fall in their plasma HIV-1 RNA levels nor a significant rise in CD4+ lymphocyte numbers while receiving HAART. At baseline, before the introduction of PI in the therapy, all patients were of immunological CDC class 1 or 2 and therefore had normal or moderately reduced CD4+ T-lymphocyte numbers. On the other hand, in all the selected HIV-1 perinatally infected children a T-lymphocyte dysfunction was observed, because the in vitro mitogen and antigen-specific responses were significantly lower than those of the control group. This observation is in agreement with previous reports showing that HIV-1 infected children may have more profound impairment in cell-mediated immunity than asymptomatic seropositive adults, even when they maintain normal CD4+ T- lymphocyte counts [35]. Marked defects in CD4+ lymphocyte function precede the decline in peripheral CD4+ lymphocyte number. An early marker of this immune defect is the inability to respond to recall antigens in vivo and in vitro[36].

Under HAART, a significant increase in the lymphocyte proliferative responses to anti-CD3 and PHA, despite persisting high viral load, have been reported [37]. In our study, the recovery of the in vitro T-lymphocyte response was earlier and sustained over time for those mitogens which explore exclusively T-lymphocyte reactivity (PHA) compared with those that induce both B and T-lymphocyte responses (PWM). It is known that the mitogenic selectivity of such polyclonal activators (PHA, PWM) is not dependent on their binding specificity for particular cell populations but, rather, reflects the heterogeneity in glycoproteins expressed on various cells [38]. In addition, their mitogenic effects for T-cells are felt to depend on their ability to bind and cross-link relevant receptors, component chains of the TCR, involved in physiological T-cell activation [38]. We could speculate that HAART induces a ‘better’ expression and function of these receptors in vivo, increasing by different measures the ability of different mitogens to activate and induce lymphocyte responses in vitro.

It has been reported that HAART induces an improvement in CD4+ T-lymphocyte reactivity for clinically relevant pathogens [3,4,17]. However, the restoration of antigen-specific T-lymphocyte responses was closely related with an increase in CD4+ T-lymphocyte numbers [17] and was associated (in the majority of cases) with a suppression of viral load.

In adults the restoration of CD4+ T-lymphocyte responses in vitro is more frequent to antigens of high exposure pathogens (C. albicans) than to those of low exposure antigens (tetanus toxoid) [17]. In contrast, in the population of children enrolled in this study, the frequency of restoration of the T-lymphocyte response was the same for both antigens (seven of seven cases). The latter observation is probably related to a more recent exposure of the immune system to tetanus toxoid (due to vaccination) in children. However, the recovery of responsiveness to C. albicans occurred earlier and was overall of a higher degree in comparison with that to tetanus toxoid. These results could be of clinical relevance. The rapid recovery of the Candida-specific CD4+ T-lymphocyte proliferation is in agreement with epidemiological data showing a rapid decrease in the incidence of candidal oesophagitis after a few months of HAART treatment in patients with advanced immune dysfunction [39].

The restoration of in vitro T-lymphocyte responsiveness despite virological failure of HAART is difficult to explain, but different hypotheses can be proposed. Improvement of in vitro lymphocyte proliferation could be explained, at least in part, by an increase in CD4+CD45RO+‘memory’ lymphocytes (as a result of recirculation) demonstrated in the early stage of HAART and not strictly associated with the suppression of viraemia [18]. However, in HIV-1 infected children treated with a protease inhibitor-containing regime, CD4+CD45RA+‘naive’ T cells were the major contributor to CD4+ T-cell expansion, as well as in those children who achieve only incomplete or minimal viral suppression [23].

Lu and Andrieu [28] have demonstrated that in vitro PIs enhance the survival of HIV-1 infected patients’ T-lymphocytes by restoring their responsiveness to immune stimuli at a dose 30-fold less than that required for achieving viral inhibition. This observation could suggest that patients experiencing a lack of virological response to HAART might have a PI concentration that is insufficient to suppress viral replication but is, however, effective for restoring T-cell responsiveness [28].

Alternatively, drug-resistant virus may have decreased replicative capacity [31,40]. Reductions in viral fitness have been observed in association with resistance to nucleoside reverse transciptase inhibitors [21]. Such decreased replication capacity would result in reduced CD4+ T lymphocyte death or increased CD4+ T lymphocyte production. Consequently, more CD4+ T lymphocytes become available to support increased viral replication. A new steady state is therefore achieved when, in the presence of a less fit virus, CD4+ T lymphocyte increases are maintained whereas HIV RNA levels return toward pretherapy baseline. However, in a previous study [13] we reported that in a group of HIV-1 infected children who remained highly viraemic while receiving HAART, only some of them showed drug-resistant HIV-1 mutants after 12 months of therapy and the development of this resistance did not influence negatively the increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte counts.

Recent studies have reported that the susceptibility of peripheral blood T cells to apoptosis decreased in HIV-1 infected adults and children under HAART [41,42]. However, whether such a phenomenon reflects the direct down-regulation of T- lymphocyte apoptosis by PIs or is merely the consequence of normalized T-lymphocyte function (such as increased proliferation to recall antigens, decreased plasma cytokines, declined serum β2-microglobulin and other soluble activation markers) [2,4,28] remains unclear. Further studies will be needed in order to clarify the mechanism of immunological correction during HAART.

In conclusion, even if the results have been obtained with a relatively small sample of children, this study indicates that HAART should be considered as a ‘crucial’ therapeutic strategy in HIV-1 infected children for its capacity to effectively reconstitute immune function. Treatment should be continued even in the absence of a significant increase in CD4+ lymphocyte numbers and/or in the presence of virological failure. Moreover, impaired immunological functions in HIV-1 infected children and their correction with HAART may have clinical implications for vaccination strategies. Functional studies of CD4+ T-lymphocytes might help to guide decisions regarding the discontinuation of treatments to prevent opportunistic infections in patients with normal levels of CD4+ lymphocytes under HAART.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sei S, Sandelli SL, Theofan G, et al. Preliminary evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) immunogen in children with HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:626–40. doi: 10.1086/314944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hugher MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogs plus indinavir in patients with of human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Autran B, Carcelain G, Li TS, et al. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4 T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV-1 disease. Science. 1997;227:112–6. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li TS, Tubiana R, Katlama C, Calvez V, Ait Mohand H, Autran B. Long-lasting recovery in CD4 T cell function and viral load reduction after highly antiretroviral therapy in advanced HIV-1 disease. Lancet. 1998;351:1682–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)10291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller BU, Nelson RP, Jr, Sleasman J, et al. A phase I/II study of the protease inhibitor ritonavir in children with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 1998;101:335–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Age, thymopoiesis, and CD4+ T-lymphocyte regeneration after intensive chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:143–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998;396:690–5. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibb DM, Newberry A, Klein N, de Rossi A, Grosch-Woerner I, Babiker A. Immune repopulation after HAART in previously untreated HIV-1-infected children. Lancet. 2000;355:1331–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resino S, Navarro J, Bellon JM, Gurbindo D, Leon JA, Munoz- Fernandez MA. Naive and memory CD4+ T cell activation markers in HIV-1 infected children on HAART. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:266–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shearer WT, Quinn TC, La Russa P, et al. Viral load and disease progression in infants infected with in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1337–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705083361901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammer SM, Kazenstein DA, Hughes MD, et al. A trial comparing nucleoside monotherapy with combination therapy in HIV-infected adults with CD4 cell counts from 200 to 500 per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1081–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Martino M, Galli L, Moriondo M, et al. Dissociation of responses to highly antiretroviral therapy: notwithstanding virologic failure and virus drug resistance, both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes recover in HIV-1 perinatally infected children. J AIDS. 2001;26:196–7. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200102010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Center for Disease Control. 1994 revised classification for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR. 1994;43:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Italian Register for HIV Infection in Children. Italian guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in children with human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection. Acta Pediatr. 1999;88:228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Martino M, Rossi ME, Azzari C, et al. Viral load and CD69 molecule expression on freshly-isolated and cultured mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes of children with perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:513–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01011.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendland T, Furrer H, Vernazza PL, et al. HAART in HIV-infected patients: restoration of antigen-specific CD4 T-cell responses in vitro is correlated with CD4 memory T-cell reconstitution, whereas improvement in delayed hypersensitivity is related to a decrease in viraemia. AIDS. 1999;13:1857–62. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00007. 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sleasman JW, Nelson RP, Goodenow MM, et al. Immunereconstitution after ritonavir therapy in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection involves multiple lymphocyte lineages. J Pediatr. 1999;134:597–606. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essajee SM, Kim M, Gonzalez C, et al. Immunologic and virologic responses to HAART in severely immunocompromised HIV-1 infected children. AIDS. 1999;13:2523–32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thuret I, Michel G, Chambost H, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy including ritonavir in children infected with human immunodeficiency. AIDS. 1999;13:81–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00011. 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deeks SG, Barbour JD, Martin JN, Swanson MS, Grant RM. Sustained CD4+ cell response after virologic failure of protease inhibitor-based regimens in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:946–53. doi: 10.1086/315334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connick E, Lederman MM, Kotzin BL, et al. Immune reconstitution in the first year of potent antiretroviral therapy and its relationship to virologic response. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:358–63. doi: 10.1086/315171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jankelevich S, Mueller BU, Mackall CL, et al. Long-term virologic and immunologic responses in human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infected children treated with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1116–20. doi: 10.1086/319274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chougnet C, Jankelevich S, Fouke K, et al. Long-term protease inhibitor-containing therapy results in limited improvement in T cell function but not restoration of interleukin-12 production in pediatric patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:201–5. doi: 10.1086/322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blazevic V, Jankelevich S, Steinberg SM, Jacobsen F, Yarchoan R, Shearer GM. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children. analysis of cellular immune responses. Clin Diagn Laboratory Immunol. 2001;8:943–8. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.5.943-948.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borkowsky W, Stanley K, Douglas SD, et al. Immunologic response to combination nucleoside analogue plus protease inhibitor therapy in stable antiretroviral therapy-experienced human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:96–103. doi: 10.1086/315672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fessel WJ, Krowka JF, Sheppard HW, et al. Dissociation of immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J AIDS. 2000;23:314–20. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu W, Andrieu JM. HIV protease inhibitors restore impaired T-cell proliferative response in vivo and in vitro: a viral-suppression- independent mechanism. Blood. 2000;96:250–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogg RS, O’Shaughnessy MV, Gataric N, et al. Decline in deaths from AIDS due to new antiretrovirals. Lancet. 1997;349:1294. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulick RM, Mellors JW, Havlir D, et al. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:734–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufmann D, Pantaleo G, Sudre P, Telenti A. CD4-cell count in HIV-1 infected individuals remaining viraemic with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Lancet. 1998;351:723–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)24010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barreiro PM, Dona MC, Castilla J, Soriano V. Patterns of response (CD4 count and viral load) at 6 months in HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:525–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199903110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledergerber B, Egger M, Opravil M, et al. Clinical progression and virologic failure on highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 patients: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 1999;353:863–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Martino M, Tovo PA, Balducci M, et al. Reduction in mortality with availability of antiretroviral therapy for children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. JAMA. 2000;284:190–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borkowsky W, Rigaud M, Krasinski K, Moore T, Lawrence R, Pollack H. Cell-mediated and humoral immune responses in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus during the first four years of life. J Pediatr. 1992;120:371–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucey DR, Melcher GP, Hendrix CW. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in US Air force. seroconversions, clinical staging, and assessment of a T helper cell functional assay to predict change in CD4+ T cell counts. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:631–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mezzaroma I, Carlesimo M, Pinter E, et al. Long-term evaluation of T-cell subsets and T-cell function after HAART in advanced stage HIV-1 disease. AIDS. 1999;13:1187–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00006. 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss A. T-Lymphocyte activation. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental immunology. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Press; pp. 411–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egger M, Hirschel B, Francioli P, et al. Impact of new antiretroviral combination therapies in HIV infected patients in Switzerland: prospective multicentre study, Swiss HIV Cohort Study. BMJ. 1997;315:1194–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7117.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuste E, Sanchez-Palomino S, Casado C, Domingo E, Lopez-Galindez C. Drastic fitness loss in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon serial bottleneck events. J Virol. 1999;73:2745–51. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2745-2751.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sloand EM, Kumar PN, Kim S, Chaundhuri A, Weichold FF, Young NS. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor modulates activation of peripheral blood CD4+ T cells and decreases their susceptibility to apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 1999;94:1021–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohler T, Walcher J, Holzl-Wening G, et al. Early effects of antiretroviral combination therapy on activation, apoptosis and regeneration of T cells in HIV-1 infected children and adolescents. AIDS. 1999;13:779–89. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]