Abstract

Previous studies have shown that autoantibodies to heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) are elevated in a significant proportion of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who are more likely to have renal disease and a low C3 level. Using samples from 24 patients, we searched for glomerular deposits of HSP90 in renal biopsy specimens from seven patients with lupus nephritis and 17 cases of glomerulonephritis from patients without SLE. Positive glomerular immunofluorescent staining for HSP90 was observed in six of seven cases of SLE and positive tubular staining in two of seven SLE patients. The staining for HSP90 was granular in nature and was located in subepithelial, subendothelial and mesangial areas. None of the non-SLE renal biopsies revealed positive staining for HSP90 deposition. Further we showed the presence of anti-HSP90 IgG autoantibodies in IgG from sera of patients with SLE as well as in normal human IgG (IVIg). In normal IgG this autoreactivity could be adsorbed almost completely on F(ab′)2 fragments from the same IgG preparation, coupled to Sepharose and could be inhibited by the effluent obtained after subjecting normal IgG to HSP90 affinity column. These findings indicate that anti-HSP90 natural autoantibodies are blocked by idiotypic interactions within the IgG repertoire. Unlike natural autoantibodies, anti-HSP90 IgG from SLE patients’ sera were only moderately adsorbed on F(ab′)2 fragments of normal IgG. These results demonstrate that immunopathogenesis of lupus nephritis is associated with HSP90 (as an autoantigen) and that the pathology is associated with altered idiotypic regulation of the anti-HSP90 IgG autoantibodies.

Keywords: autoantibodies, HSP90, idiotypes, SLE

INTRODUCTION

Heat shock proteins (HSP) are a family of ubiquitous and phylogenically highly conserved proteins [1]. Autoreactivity to HSP is often associated with autoimmune pathology. Previous studies have demonstrated the presence of autoantibodies to the HSP90 in a significant proportion of patients with systemic lupus. Anti-HSP90 autoantibodies of the IgG class were detected in approximately 50%[2] and 26%[3] and of IgM class in 35%[3] of unselected patients with SLE. The presence of high titre anti-HSP90 autoantibodies was found to correlate with renal involvement and low C3 levels [3]. Although HSP90 is an intracytoplasmic protein, surface expression of HSP90 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells was found in approximately 25% of the patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) during active disease [4]. It has been shown that the increased expression of HSP90 is due to the enhanced transcription of the HSP90α gene [5]. Although these results indicate an association of anti-HSP90 autoreactivity with SLE, no direct involvement of HSP90 and anti-HSP90 antibodies in the pathogenesis of the disease has been proven. Moreover, normal human IgG (represented by pooled preparation for i.v. use – IVIg) has been found to contain considerable amounts of low-affinity anti-HSP90 natural autoantibodies [6].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of HSP90 as an autoantigen in the renal injury in SLE by looking for HSP90 containing immune complexes in kidney biopsies of lupus patients. Since the most probable cause for such deposits is the presence of high titre anti-HSP90 autoantibodies in the sera of SLE patients and considering the fact that natural anti-HSP90 autoantibodies are found also in healthy individuals, we examined the possibility of using this autoreactivity as a model to study the relation between natural and disease-associated autoantibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monoclonal antibodies

Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for human HSP90 has been previously described. Briefly, BALB/c mice were immunized with purified HSP90 and hybridomas were raised following the routinely used procedure. Mouse myeloma P3U1 was used as a fusion partner. The hybridomas were screened by ELISA and Western blot and subcloned to monoclonality (at least twice). Monoclonal antibody 3F12 was selected on the basis of its high affinity and specificity to HSP90 [7].

Purification of HSP90

HSP90 was purified from spleen obtained from the Pathology department of the Medical University in Sofia. The tissue was frozen within 30 min of splenectomy in aliquots of 50g. An extract of cytosolic proteins was prepared by homogenizing 50g of tissue in 150 ml of 0·03m carbonate buffer pH 7·1 containing 5 mm PMSF, 5 mg/ml aprotinin. The homogenate was cleared by ultracentrifugation and subjected to ammonium sulphate precipitation at 50% after which the supernatant was brought to 70% saturation. The precipitate was dissolved and dialysed extensively against 0·02 m phosphate buffer, pH 7·4, 1mm EDTA, 0·2m NaCl. The solubilized proteins were then subjected to ion-exchange chromatography on a MonoQ column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) using a gradient of NaCl from 0·2 to 0·6m in phosphate buffer, pH 7·4. The fractions with the highest content of protein that migrated at about 90 kDa upon SDS-PAGE were pooled and fractionated further on a hydroxyapatite column using a gradient of 0·02–0·3m phosphate buffer pH 7·0 containing 0·1mm EDTA and 15 mm 2-mercaptoethanol. The fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using rat monoclonal antibody to human HSP90 16F1 (SPA-835, StressGen Biotechnologies Corp., Victoria BC, Canada). Fractions containing HSP90 at apparent homogeneities were pooled, dialysed against PBS, aliquoted and kept at −70°C until use. Purified HSP90 migrated in SDS-PAGE as a single protein band of approximately 85–90 kDa. The band specifically stained with antihuman HSP90 monoclonal antibody. The yield of the purification procedure was 5 mg of antigen per 50g wet weight of starting material.

Patients’ sera and biopsy material

The SLE patients’ sera were obtained from the Rheumatology Department at the Medical University in Sofia. All patients were classified as having SLE and fulfilled the ARA revised criteria for the classification of SLE [8]. The diagnosis of SLE was made if four of the listed manifestations were present. The activity of the disease was assessed according to the BILAG score [9].

The renal tissue samples were obtained from the Department of Pathology, Medical University, Sofia. Non-selected, consecutive renal biopsy material from seven hospital patients with SLE were studied along with material from 17 cases of glomerulonephritis with other aetiology, including rheumatoid arthritis, renal amyloidosis, vasculitis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus type I and IgA glomerulonephritis.

Tissue samples and immunofluorescence studies

Cryostat tissue sections (4 μm thick) from needle biopsy specimens were air-dried for 1 h and fixed in cold acetone (−20°C) for 10 min, then washed twice in PBS. The slides were incubated at room temperature (RT) in a humidified chamber with MoAb 3F12 for 1h, washed three times for 5 min in PBS pH 7·3 and then FITC conjugated antimouse IgG antibody (SAPU, Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK) diluted in 2% BSA (Serva, Feinbiochemica, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions was added and the sections were incubated for 1h at RT. Following extensive washing in PBS pH 7·3 the sections were mounted in 50% glycerol in PBS (pH 8·2) and viewed using an epifluorescent microscope (Leitz, Austria). The sections were photographed with an automatic camera (WILD MPS 12, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) on Kodak T-400 CN films. Slides incubated with serum from non-immune BALB/c mice diluted 1:100 in 10% FCS (Gibco BRL, Inchinnan UK), RPMI-1640 culture medium (Flow Laboratories, Irvine, Scotland, UK) was used as negative controls. Sections from all biopsy specimens were also stained routinely for IgA, IgG and IgM as well as for complement components C1, C3 and C4 as a part of the diagnostic procedure. Two investigators judged the intensity of immunofluorescence independently; intensity of staining was graded semiquantitatively on a negative to 4+ scale; a positive staining was taken as staining of at least 2+ in intensity.

IgG purification on HiTrap protein G affinity column

Samples of 1ml from each serum were centrifuged and filtered through 0·45 mm filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and IgG was isolated by affinity chromatography using HiTrap Protein G Sepharose column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The bound IgG was eluted by washing the column with 0·1m glycine-HCL pH 2·8 and the pH was adjusted immediately using 1 m Tris-HCL pH 9·0. The eluted IgG samples were aliquoted and stored at −20°C.

IgM purification from patients’ sera

IgM was isolated by affinity chromatography using anti-IgM affinity column (Sigma). The effluent fractions, obtained after passing SLE patients’ sera through the HiTrap protein G Sepharose column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) were centrifuged, filtered through 0·45 μm filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and applied on an anti-IgM affinity column. Bound antibodies were eluted using glycine/HCL (0·1 m) buffer of pH 2·8, 2 m NaCl followed by PBS and then diethanolamin (0·1 m) buffer pH 11, 2m NaCl. The eluates obtained at different pH were brought to pH 7·0, pooled and dialysed against PBS.

Preparation of F(ab′)2 affinity columns

A sample of 30 mg IVIg was dissolved in acetate buffer (0·1 m, pH 4) and co-incubated with 0·6 mg pepsin for 16 h at 37°C. After adjustment to pH 7·5 with Tris buffer (2 m, pH 11) the sample was dialysed against PBS pH 7·2 and passed through a Protein G Sepharose® Fast Flow column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

For preparing IgM F(ab′)2 from IgM a sample or 15mg IVIgM (LFB, Les Ulis, France) was mixed with acetate buffer (0·1m, 0·2m NaCl, pH 4) and co-incubated with 0·75 mg pepsin for 16h at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adjusting the pH to 7 by adding Tris buffer (2 m, pH 11). The F(ab′)2 fragments were purified from the mixture by size exclusion chromatrography on a Sephacryl S200 15/800 mm column.

The affinity columns were prepared using 0·6g CNBr activated Sepharose 4B and 6 mg F(ab′)2 following the manufacturer's instructions. The column was equilibrated with PBS pH 7·2.

Affinity purification of antibodies

Immunoadsorbent columns were prepared with purified human HSP90 coupled to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Seven milligrams of protein were used for coupling to 3·5 ml of bed volume of CNBr-activated Sepharose. One g of IVIg (Novartis, Switzerland) dissolved in 100 ml of PBS was loaded onto the immunoadsorbent column and run twice at a speed of 1ml/min at room temperature. The column was washed with PBS until the absorbency of the flow-through at 280 nm reached baseline values. Bound antibodies were eluted using glycine/HCL (0·1 m) buffer, pH 2·8, 2m NaCl followed by PBS and then diethanolamin (0·1 m) buffer pH 11, 2m NaCl. The eluates obtained at different pH were brought to pH 7·0 and pooled. Two ml of the flow-through fractions were allowed to run through the sorbents for two more cycles and further used as effluent fractions. Eluates and effluents were dialysed against PBS.

Immunoadsorbent columns were prepared also with human IgM purified from SLE patients’ sera and from IVIgM (LFB, Les Ulis) as well as from F(ab′)2 IVIg and IVIgM coupled to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The anti-HSP90 antibodies from SLE patients’ sera or IVIg (Novartis, Switzerland) were loaded in 3 ml of PBS on the immunoadsorbent column and were incubated for 2h at room temperature and the effluent was collected.

Cross-blot assay

A prewetted piece of PVDF membrane was inserted into the miniblotter and incubated for 2h with a series of twofold dilutions of the antigen starting at 100 μg/ml. All procedures were performed at room temperature. The membrane was blocked with TBS pH 8·0, 0·2% Tween 20 for 1 h. Further the membrane was incubated in miniblotter with IgG antibodies to be tested for 2h. For the cross-blot the direction of the slots was perpendicular to that of the imprints of the slots that had contained antigen solutions during the first incubation. After washing three times with TTBS the membranes were incubated in a solution of secondary antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, USA). Immune reactivities were revealed using the nitroblue tetrazolium/bromo-chloro-indolyl-phosphate chromogenic substrate. Quantification of immunoreactivities was performed by densitometry in reflective mode using a scanner (UMAX) linked to a PC computer. The data were analysed using software ImageTool v2·0 for Windows (UTHSCSA, San Antonio, TX, USA). For quantification of cross-blot the densitometric profiles of the lanes loaded with antigen were taken. The baseline formed by the minima along the immunoreactivity profiles was subtracted from the densitometric profile. The intensity of the staining was represented by the average grey level of the specifically stained regions.

Statistics

The quantitative data differences were tested using Mann– Whitney U-test with level of significance P < 0·05.

RESULTS

Immunofluorescence studies on renal biopsy material

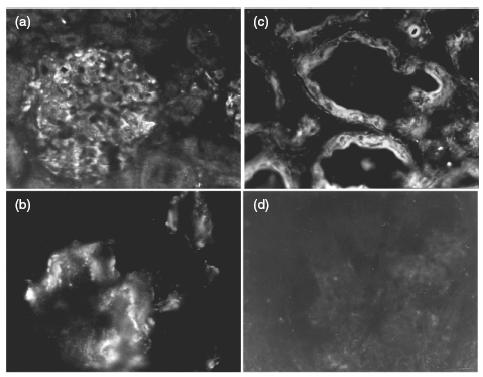

A total of 24 samples of renal tissue biopsies from patients with glomerulonephritis were treated with MoAb 3F12 to detect any depositions of HSP90 in the kidneys. All samples of renal tissue sections usually showed a weak intracellular staining. However, unequivocal specific glomerular staining with MoAb 3F12 was found in six of seven samples from patients with SLE. Two of the patients with SLE showed positive tubular staining with the MoAb 3F12 and the histopathological studies revealed a tubular atrophy to be manifested in one of these cases.

Three major patterns of deposition of HSP90 could be distinguished: subendothelial, subepithelial and deposits in the mesangium. The staining of all deposits along the glomerular basement membrane was finely granular or linear. Mesangial deposits were irregular with homogeneous strands lying between capillary loops. Tubular basement membrane deposits of HSP90 were granular. Examples of immunofluorescent staining for HSP90 are shown in Fig. 1. The immunofluorescent staining for HSP90 of the kidney biopsy material sections from the studied cases of glomerulonephritis not associated with SLE were classified as negative, although structure of the kidney was visualized as can be seen in Fig. 1d. No staining was observed in sections in which the primary antibody was replaced by appropriately diluted normal BALB/c mouse serum. These results clearly show that HSP90 is found in deposits in the kidney and is specific of SLE glomerulonephritis.

Fig. 1.

Indirect immunofluorescene. Cryostat sections of renal biopsy material from patients with glomerulonephritis were treated consequently with anti-HSP90 monoclonal antibody (MoAb 3F12) and antimouse IgG conjugated with FITC. (a) Glomerulus from SLE patient. Mostly subendothelial and subepithelial glomerular pattern of staining. Original magnification 250×. (b) Glomerular capillary loop from SLE patient. Intense mesangial and subepithelial granular staining. Original magnification 1250×. (c) Tubular staining and tubular atrophy in SLE patient. Original magnification 500×. (d) Glomerulus from patient with non-SLE associated glomerulonephritis. No staining for HSP90 can be seen. Original magnification 250×.

Comparison between the anti-HSP90 reactivity of IgG from healthy individuals and that from SLE patients

Previous experiments have shown that preparations of pooled normal human IgG (IVIg) contain anti-HSP90 autoantibodies and the presence of anti-HSP90 autoantibodies in SLE sera has been published previously [2,3]. In order to compare natural and disease-associated anti-HSP90 IgG autoantibodies in the present study, IgG was purified from sera from 15 SLE patients and from a pool of four healthy individuals’ sera by Protein G affinity chromatography. Anti-HSP90 autoantibodies were affinity purified from the IgG preparations, as well as from IVIg. The later was used because the pooling of immunoglobulins from over 10 000 healthy individuals in the IVIg preparations ensures that the reactivities found therein represent a constant ingredient of the normal human IgG repertoire.

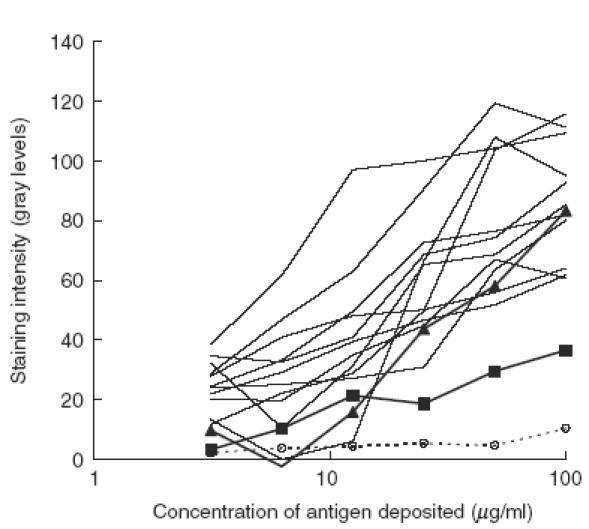

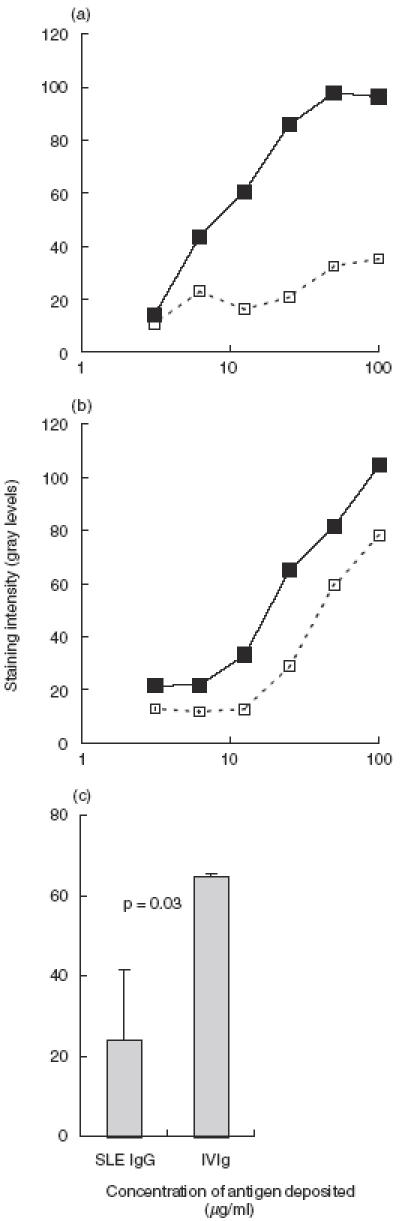

The specific reactivity of the autoantibodes was tested in cross-blot on human HSP90 (Fig. 2). All samples were adjusted to 0·1 mg/ml IgG content and were tested simultaneously on the antigen, deposited in a series of dilutions on PVDF membrane. Most of the anti-HSP90 autoantibodies from SLE sera showed higher apparent affinity to the antigen than anti-HSP90 from healthy donors and IVIg, but there was no clear cut difference between natural and disease-associated autoantibodies.

Fig. 2.

Reactivity with human HSP90 of anti-HSP90 antibodies, affinity-purified from different IgG preparations in cross-blot. The antigen is deposited on PVDF membrane in series of dilutions. All antibodies are applied at concentration 0·1 mg/ml of IgG. The figure shows graphically the results from the densitometry of the cross-blot. Thin lines: binding of IgG samples from SLE sera; thick lines: binding of IgG from healthy donors (filled triangles: pooled IgG from five healthy donors; filled squares: IVIg), dashed line with open circles: flow-through of IVIg through HSP90 column. On the abscissa: the concentration of HSP90 during deposition on PVDF membrane. On the ordinate: staining intensity, measured by densitometry on a grey scale of 256 discrete levels. The actual data are obtained by subtraction of the background reactivity of the antibodies to the blocked membrane.

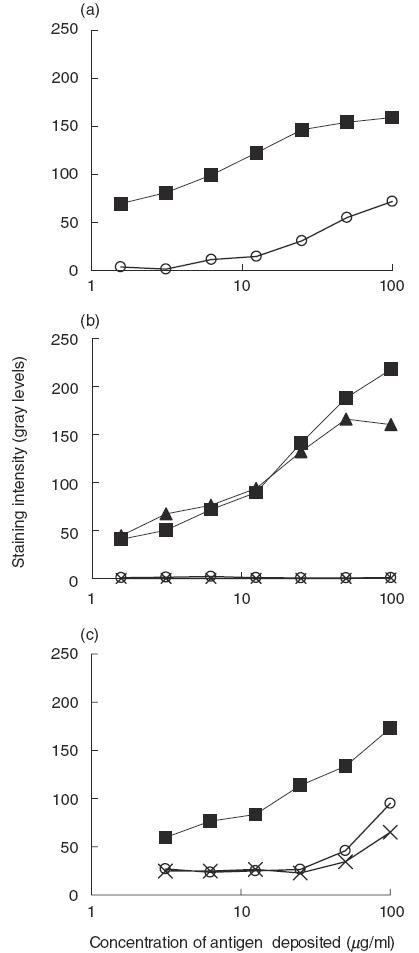

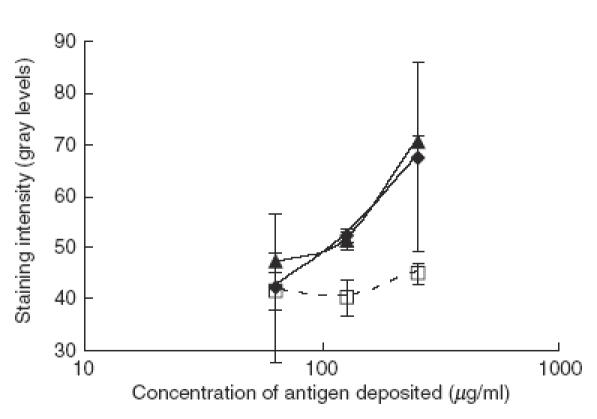

In order to test the hypothesis that these two types of antibodies differ in their idiotypic properties, purified IgG from patients with SLE or IVIg were adsorbed on a column of F(ab′)2 fragments from IVIg, and from IVIgM coupled to Sepharose. The concentration of the IgG samples was brought to 1 mg/ml before passing them eight times through each of the columns. The specific antibody reactivity to HSP90 of the effluent fractions and of the unfractionated IgG preparation was compared next in cross-blot. Passing of IVIg and lupus patients’ IgG through a column containing F(ab′)2 fragments of IVIgM did not change the anti-HSP90 activity in any of the two preparations (Fig. 3). To test the importance of the intact structure of the IgM molecules, affinity columns were prepared with pooled normal IgM or IgM from sera from patients with SLE, coupled to Sepharose. Pooled normal IgG was passed through the normal IgM column (Fig. 4a) while IgG from two SLE patients, respectively, was passed through columns with autologous IgM (Fig. 4b). In all three cases the passing of IgG through whole IgM columns depleted them of their anti-HSP90 activity. Moreover, passing of normal and SLE IgG in the same concentration through a column of normal IgM adsorbed their anti-HSP90 activity to a similar extent (Fig. 4c). These results indicate that the anti-HSP90 IgG autoantibodies in pooled normal IgG and in SLE patients’ IgG interact strongly with whole IgM, irrespective of its origin, but none appeared to interact with F(ab′)2 fragments of normal IgM.

Fig. 3.

Adsorption of anti-HSP90 reactivity of anti-HSP90 antibodies (filled symbols) from IVIg (a), from two lupus sera (b) and from a single lupus serum (c) by passing through affinity column prepared from IgM. (a) IVIgM, open circles; (b) autologous IgM, open circles and crosses. (c) Effect of both columns (open circles, IVIgM; crosses, autologous) assayed in cross-blot. For the conditions of the cross-blot see Fig. 2.

Fig. 4.

Anti-HSP90 autoreactivity in normal (IVIg) (circles) and SLE patient's IgG (squares) before (filled symbols) and after (open symbols) passing through IVIgM F(ab′)2 affinity column. Densitometry data from cross-blot. The conditions are the same as in the experiment presented in Fig. 2.

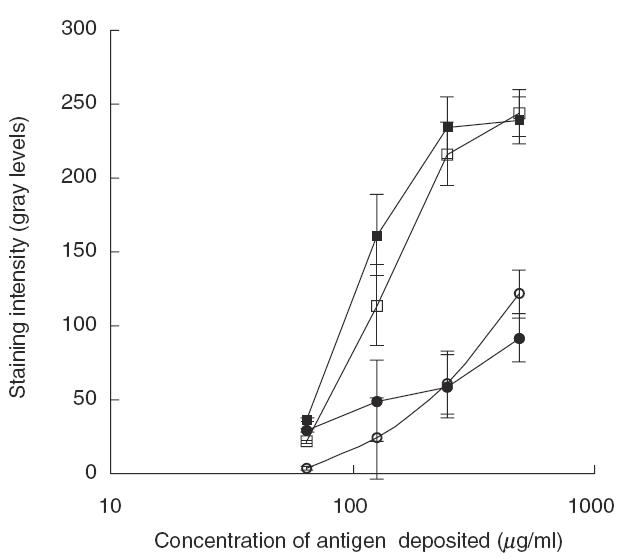

Next, the idiotypic interactions of the anti-HSP90 IgG autoantibodies within the IgG repertoire were tested. Passing of IVIg through F(ab′)2 of IVIg column led to a significant decrease in the anti-HSP90 autoantibody reactivity of the effluent fraction as compared to the unfractionated preparation (Fig. 5a). When IgG from SLE sera were passed through IVIg F(ab′)2 column, only a modest decrease in the anti-HSP90 activity of the effluent fraction was observed compared to the unfractionated IgG (Fig. 5b). Thus anti-HSP90 autoantibodies from normal IgG bind stronger to F(ab′)2 fragments from normal IgG than SLE associated anti-HSP90 autoantibodies.

Fig. 5.

Effect of reducing the content of anti-idiotypic antibodies in IgG preparations on the antiself HSP90 reactivity assayed by cross-blot. IVIg (a) or SLE patients’ IgG samples ((b) shows a typical case) were passed through affinity column containing F(ab′)2 fragments prepared from IVIg. The anti-HSP90 reactivity of the effluents (dashed line) was compared to that of the untreated IgG sample (solid line). The conditions of the cross-blot are as in the experiment described in Fig. 2. The differences in the reactivity of untreated and treated IgG to antigen deposited at 0·05 mg/ml on PVDF membrane were quantitatively compared between IgG from SLE patients and IVIg (c). Results are presented for IgG samples from eight SLE sera and IVIg, all tested in two experiments at 0·1 mg/ml in cross-blot. The fall in anti-HSP90 reactivity of IVIg after passing through F(ab′)2 column is significantly greater than that of SLE IgG (P < 0·05, Mann–Whitney U-test).

The observed difference in the idiotypic interactions between natural and SLE associated anti-HSP90 IgG was quantified more precisely by comparing the binding to HSP90 of multiple samples at one optimal concentration of IgG. Eight individual samples of disease-associated anti-HSP90 autoantibodies and two samples of natural anti-HSP90 antibodies were tested before and after passing through the column containg F(ab′)2 fragments from IVIg. The binding of 0·1 mg/ml of IgG to HSP90, deposited on PVDF membrane in concentration 0·05 mg/ml, was tested in cross-blot. The data from two experiments, carried out under identical conditions, were analysed. Figure 5c shows the mean differences of the intensity of the binding as measured by densitometry of the cross-blot. Adsorbing on a F(ab′)2 column led to a significantly greater decrease in the anti-HSP90 activity of IVIg compared to that of the SLE IgG (P < 0·05, Mann–Whitney U-test).

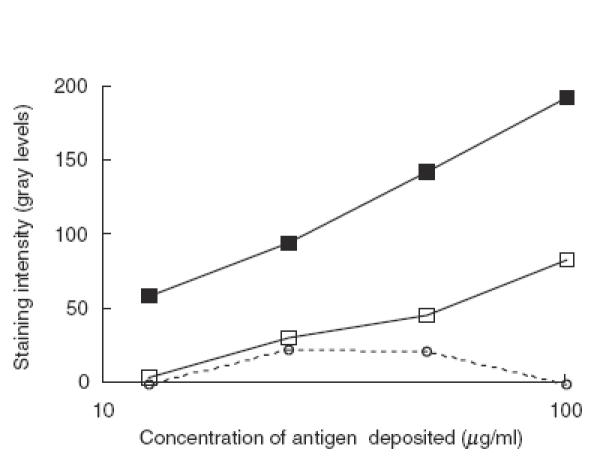

In order to rule out the possibility that the adsorbing of the anti-HSP90 activity is due to non-specific protein–protein interactions, the same experiment was repeated with a F(ab′)2 affinity column, prepared from IVIg, preadsorbed on a F(ab′)2 affinity column. A sample of IVIg was run twice through the F(ab′)2 affinity column, prepared from whole IVIg, to adsorb the anti-idiotypic antibodies. F(ab′)2 fragments, prepared from the effluent, were coupled to Sepharose in the same concentration as for the first F(ab′)2 affinity column (this second column is designated hereafter F(ab′)2-Id). The effect of passing through each of these two F(ab′)2 columns on the anti-HSP90 activity of IVIg was tested in cross-blot (Fig. 6). While the F(ab′)2 column retains most of the anti-HSP90 activity, passing IVIg through a F(ab′)2-Id column did not change it significantly, thus demonstrating that the IgG/IgG interactions of anti-HSP90 IgG, observed in the previous experiments, are due most probably to specific anti–idiotypic interactions.

Fig. 6.

Specificity of the anti-idiotype interactions leading to reduced anti-HSP90 activity in IVIg. Samples of IVIg were passed through F(ab′)2 (dashed line) and F(ab′)2-Id columns (filled diamonds) (see text for details) and their anti-HSP90 reactivity was compared to that of non-treated IVIg (filled triangles) in cross-blot. For the conditions of the cross-blot see Fig. 2. Only a column with F(ab′)2 fragments, derived from normal IgG with intact repertoire, retains the anti-HSP90 reactivity of IVIg while a column with F(ab′)2 fragments from the IgG pool, from which the anti-idiotypic antibodies have been removed, does not change this reactivity.

Next we tested the possibility that anti–idiotypic interactions interfere with the anti-HSP90 natural autoreactivity in purified normal IgG, suppressing it partially. To this end 2 ml IVIg at 1 mg/ml were adsorbed by passing several times through the HSP90 column to reduce maximally the anti-HSP90 activity. This effluent was divided into two and one of the aliquots adsorbed further on the F(ab′)2 column. Anti-HSP90 antibodies from IVIg were added to each of these effluents (IVIg depleted of anti-HSP90 and IVIg depleted both of anti-HSP90 and anti-Id) in the ratio of 1:13 and the mixtures were incubated overnight at 4°C. The reactivity to HSP90 of the preincubated mixtures of affinity purified anti-HSP90 antibodies with HSP90 column effluent was tested in cross-blot in comparison to pure anti-HSP90 antibodies at the same concentration of anti-HSP90 IgG (Fig. 7). The effluent fraction, adsorbed on HSP90 column, suppressed the anti-HSP90 reactivity of the specific fraction almost completely, while the effluent of HSP90 column which was passed in addition through a F(ab′)2 column suppressed the specific reactivity only moderately. Together these findings indicate that anti-idiotypic IgG antibodes block much more efficiently anti-HSP90 autoantibodies’ reactivites in the normal IgG repertoire than in the IgG repertoire of SLE patients.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of anti-HSP90 reactivity of anti-HSP90 antibodies from IVIg (filled squares) by flow-through of HSP90 affinity column (dashed line, open circles) and by flow-through of HSP90 affinity column also passed through a F(ab′)2 affinity column (open squares) assayed in cross-blot. For the conditions of the cross-blot see Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates to our knowledge for the first time the presence of self-HSP90 in the glomerular (subendothelial, subepithelial and mesangial) and tubular immune complex deposits in the kidneys of patients with lupus nephritis. The appearance of the glomerular and tubular staining with the anti-HSP90 antibody 3F12 in renal biopsy sections from SLE patients corresponded to that observed with antibodies specific for immunoglobulin and for complement components in cross-sections of the same samples. The presence of HSP90 in the renal deposits is characteristic of SLE because no deposition of HSP90 was found in the kidney biopsies of patients with glomerulonephritis with non-SLE origin. There was no correlation found between the onset of the disease, the disease treatment histories and the presence of renal HSP90 deposits.

Although the aetiology of SLE is still unclear, deposition of antigen–antibody complexes plays a role in the tissue damage of blood vessels and kidney [10]. Autoantibodies of different specificities are found in the sera of patients with SLE. Antibodies to double-strand DNA are found in 52% of the patients with SLE [11], anti-Sm antibodies – in 25%[12], antibodies to SS-A/Ro and SS-B/La (components of RNP particles) – in 25% and 10%, respectively [13], etc. Anti-HSP90 antibodies were present in 30–50% of the patients with SLE and those patients were more likely to have renal disease and a low C3 level [2,3]. In this study the presence of anti-HSP90 autoreactivity was found in 6/10 sera from lupus patients with active disease according to their BILAG score [9]. The presence of high titre anti-HSP90 autoantibodies in the sera of SLE patients seems the most probable cause for the deposition of HSP90 in the kidneys. The increased expression of HSP90, found in lupus [5,14], could hardly explain the bright glomerular and tubular staining found. Neither can it, alone, be the cause of the kidney deposits. HSP90 is abundant in normal tissues and the relative increase found is hardly enough to explain the deposits. With these considerations the results of the present study are in support of the hypothesis that anti-HSP90 autoreactivity is involved specifically in the renal pathology associated with SLE.

Apart from high titre anti-HSP90 autoantibodies found in the sera of SLE patients, it has been shown that natural anti-HSP90 autoantibodies also exist in the sera of healthy individuals [6]. Therefore anti-HSP90 autoreactivity was used as a model to compare the physiological and SLE-associated pathological IgG autoreactivity. The average apparent affinity of the antibodies isolated from SLE patients’ sera was higher than that of the natural antibodies, but no discrete difference was found between natural and SLE associated anti-HSP90 autoantibodies.

Previously it has been demonstrated that SLE associated autoantibodies have a more diverse repertoire of autoreactivities as compared to the natural antibodies [15]. It has also been found that autoantibodies in SLE are not blocked by the serum factors that normally mask the natural autoreactivity in the sera of healthy individuals and are most probably related to anti-idiotypic interactions [16–18].

IgG autoantibodies to HSP90 from SLE patients are found to be less idiotypically regulated within the normal IgG repertoire than natural anti-HSP90 antibodies. These results were supported by the demonstration of an anti-idiotypic inhibition of natural anti-HSP90 autoantibodies by IgG antibodies which was more pronounced in normal than in SLE IgG. A similar inhibition by anti-idiotypic IgG antibodies of natural antiribosomal P protein IgG autoantibodies has been found previously in normal but not in SLE sera [19]. Further presence of anti-DNA and antiphospholipid antibodies, together with their anti-idiotypic antibodies in IVIg, has been demonstrated by Krause et al.[20]. These autoreactivities appear not only physiologically controlled in IVIG but the complete IgG repertoire present therein seems to be beneficial in experimental SLE and primary antiphospholipid syndrome [21]. The importance of the idiotypic network for autoimmune pathogenesis has also been demonstrated in the case of antiproteinase-3 (anti-PR3) ANCA. The specific 5/7 anti-Id antibodies blocked the activity of these ANCA [22] and injecting anti-PR3 autoantibodies could induce disease in mice by the idiotypic cascade Ab1-Ab2-Ab3 [23].

No difference in the idiotypic interactions could be found with respect to the normal IgM repertoire. This finding seems at variance with previous reports of lower anti-idiotypic connectivity of IgG with IgM in pathology associated anti-DNA, anti-RNP, antithyroglobulin and anti-endothelial autoantibodies compared to natural antibodies [15,16,24]. The data presented here do not exclude the possibility of the existence of disturbed IgM/IgG idiotypic interactions of anti-HSP90 autoantibodes in SLE. The affinity range in which this may be observable when the IgM antibodies are immobilized may be too narrow, the solid phase giving additional advantage to the higher avidity of the pentamer IgM. In the case of IgM F(ab′)2 affinity column, the inhibitory IgG anti-idiotypic antibodies, present in the sample, may be of higher affinity and thus compete with the immobilized IgM F(ab′)2.

Thus pathogenic anti-HSP90 autoreactivity seems specific of SLE, since self-HSP90 participates in the formation of the kidney deposits only in SLE glumerulonephritis. It appears to be a functional expression of the naturally occurring anti-HSP90 IgG autoreactivity due, at least in part, to an altered idiotypic the IgG repertoire in the sera of SLE patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by INSERM grant 4E007C, NATO Linkage grant CNS 972092 and the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Research National Research Fund (grant K702)

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minota S, Koyasu S, Yahara I, Winfield J. Autoantibodies to the heat-shock protein hsp90 in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:106–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI113280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy SE, Faulds GB, Williams W, Latchman DS, Isenberg DA. Detection of autoantibodies to the 90 kDa heat shock protein in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:923–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.10.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erkeller-Yuksel FM, Isenberg DA, Dhillon VB, Latchman DS, Lydyard PM. Surface expression of heat shock protein 90 by blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 1992;5:803–14. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(92)90194-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twomey BM, Dhillon VB, McCallum S, Isenberg DA, Latchman DS. Elevated levels of the 90 kD heat shock protein in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are dependent upon enhanced transcription of the hsp90 beta gene. J Autoimmun. 1993;6:495–506. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1993.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pashov A, Kenderov A, Kyurkchiev S, et al. Autoantibodies to heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) in the human natural antibody repertoire. Int Immunol. 2002;14:453–61. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenderov A, Pashov A, Kyurkchiev S, Kehayov I. Development of a panel of monoclonal anti-heat shock proteins (HSP90) antibodies. Comp R Acad Bulg Sci. 2000;53:101–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay EM, Bacon PA, Gordon C, et al. The BILAG index: a reliable and valid instrument for measuring clinical disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Q J Med. 1993;86:447–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrmann M, Voll RE, Kalden JR. Etiopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Today. 2000;21:424–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emlen W, Jarusiripipat P, Burdick G. A new ELISA for the detection of double-stranded DNA antibodies. J Immunol Meth. 1990;132:91–101. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90402-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp GC. Anti-nRNP and anti-Sm antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:757–60. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Synkowski DR, Reichlin M, Provost TT. Serum autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus and correlation with cutaneous features. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:380–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephanou A, Conroy S, Isenberg DA, et al. Elevation of IL-6 in transgenic mice results in increased levels of the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) and the production of anti-hsp90 antibodies. J Autoimmun. 1998;11:249–53. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ronda N, Haury M, Nobrega A, Kaveri SV, Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD. Analysis of natural and disease-associated autoantibody repertoires: anti-endothelial cell IgG autoantibody activity in the serum of healthy individuals and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1651–60. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.11.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurez V, Kaveri SV, Kazatchkine MD. Expression and control of the natural autoreactive IgG repertoire in normal human serum. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:783–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melero J, Tarrago D, Nunez-Roldan A, Sanchez B. Human polyreactive IgM monoclonal antibodies with blocking activity against self-reactive IgG. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:393–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kra OZ, Lorber M, Shoenfeld Y, Scharff Y. Inhibitor (s) of natural anti-cardiolipin autoantibodies. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 1993;93:265–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb07977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan ZJ, Anderson CJ, Stafford HA. Anti-idiotypic antibodies prevent the serologic detection of antiribosomal P autoantibodies in healthy adults. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:215–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krause I, Blank M, Shoenfeld Y. Anti-DNA and antiphospholipid antibodies in IVIG preparations: in vivo study in naive mice. J Clin Immunol. 1998;18:52–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1023239904856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause I, Blank M, Kopolovic J, et al. Abrogation of experimental systemic lupus erythromatosus and primary antiphospholipid syndrome with intravenous gamma globulin. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1068–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strunz HP, Csernok E, Gross WL. Incidence and disease associations of a proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody idiotype (5/7 Id) whose antiidiotype inhibits proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody antigen binding activity. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:135–42. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank M, Tomer Y, Stein M, et al. Immunization with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) induces the production of mouse ANCA and perivascular lymphocyte infiltration. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 1995;102:120–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb06645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melero J, Núñez-Roldán A, Tarragó D, Wichmann I, Sánchez B. Lack of suppressive antibody activity in sera from patients with active-phase autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity. 1998;28:47–56. doi: 10.3109/08916939808993844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]