Abstract

Previously, we have found that immunosuppressive macrophages (Mφs) induced by Mycobacterium intracellulare-infection (MI-Mφs) required cell contact with target T cells to express their suppressor activity against concanavalin A (Con A)-induced T cell mitogenesis. In this study, we examined the profiles of cell-to-cell interaction of MI-Mφs with target T cells. First, MI-Mφs displayed suppressor activity in an H-2 allele-unrestricted manner, indicating that MHC molecules are not required for cell contact. The suppressor activity of MI-Mφs was reduced markedly by paraformaldehyde fixation or treatment with cytochalasin B or colchicine, indicating that vital membrane functions are required for their suppressor activity. Secondly, the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs was independent of cell-to-cell interaction via CD40 ligand/CD40 and Mφ-derived indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which causes rapid degradation of tryptophan in T cells. Thirdly, precultivation of splenocytes with MI-Mφs, allowing cell-to-cell contact, reduced Con A- or anti-CD3 antibody-induced mitogenesis but not phorbol myristate acetate/calcium ionophore A23187-elicited proliferation of T cells. In addition, co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs caused marked changes in profiles of the tyrosine phosphorylation of 33 kDa, 34 kDa and 35-kDa proteins and, moreover, the activation of protein kinase C and its translocation to the cell membrane. It thus appears that suppressor signals of MI-Mφs, which are transmitted to the target T cells via cell contact, principally cross-talk with the early signalling events before the activation of PKC and/or intracellular calcium mobilization.

Keywords: immunosuppressive macrophages, Mycobacterium intracellulare, signal transduction suppressor signal, T cell mitogenesis

INTRODUCTION

The generation of immunosuppressive macrophages (Mφs) is encountered frequently in hosts with mycobacterial infections, and leads to depressed cellular host immunity in the advanced stage of infection [1–3]. We have found previously that immunosuppressive Mφs induced in Mycobacterium intracellulare (MI)-infected mice (MI-Mφs) exhibited strong suppression of concanavalin A (Con A)-induced T cell mitogenesis by inhibiting IL-2 receptor expression and IL-2 production of Con A-stimulated T cells [4–6] and that MI-induced generation of immunosuppressive Mφs in vivo was mediated by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in combination with interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or interleukin-1 (IL-1) [7]. The suppressor activity of MI-Mφs was mediated by certain soluble mediators including nitric oxide (NO), free fatty acids (FFA), phosphatidylserine (PS), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which were produced by the MI-Mφs themselves [8–10]. Although MI-Mφs produced large amounts of IL-10, this immunosuppressive cytokine did not mediate the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs [8]. We also found that cell-to-cell contact of MI-Mφs with target T cells may be required for full manifestation of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs [10]. This suggests that cell contact may also play important roles in intercellular transmission of the suppressive signals from MI-Mφs to target T cells, as do the above soluble mediators, in MI-Mφ-mediated suppression of T cell mitogenesis. In the present study, we studied detailed profiles of cell-to-cell interaction of MI-Mφs with target T cells and subsequent cross-talk of MI-Mφ-derived suppressor signals with T cell signalling pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms

MI N-260 strain isolated from sputum of a patient with pulmonary MI infection was used. It belonged to serovar 16 in Schaefer's seroagglutination test.

Mice

Eight to 10-week-old male BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (Japan Clea Co., Osaka, Japan) and CBA/JN mice (Charles River Co., Kanagawa, Japan) were used.

Special agents

Special agents used in this study were as follows: Con A (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (Sigma), Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (Calbiochem Co., La Jolla, CA, USA), somatostatin (Sigma), cytochalasin B (Sigma), colchicine (Sigma), 1-methyl-l-tryptophan (Aldrich Chemistry Co., Milwaukee, WI, USA), anti-mouse CD40 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) (Serotec Ltd, Oxford, UK), anti-mouse CD3 MoAb (Serotec), anti-mouse CD28 MoAb (Pharmingen Co., San Diego, CA, USA), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine MoAb (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, USA), [3H]thymidine (3H-TdR) (NEN Life Science Products Inc., Boston, MA, USA), and mitomycin C (Kyowa Hakko Kogyo Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Medium

RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 25 mm HEPES, 2 mm glutamine, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, 100 units/ml of penicillin G, 5 × 100−5m 2-mercaptoethanol and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) was used for cell culture.

Suppressor activity of MI-Mφs

Spleen cells (SPCs) were harvested from mice infected intravenously with 1 × 108 colony-forming units of MI at 2–3 weeks after infection and cultured in 0·2 ml of the medium in four wells each of flat-bottom 96-well microculture plates at cell densities of 5 × 105–2 × 106 cells/well at 37°C in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2–95% humidified air) for 2 h. The wells were rinsed vigorously with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% FBS by pipetting and then 0·1 ml of the medium was poured onto the resulting wells. This procedure usually gave more than 90% pure Mφ monolayer cultures, with active pinocytic ability of neutral red and with phagocytic ability against latex particles, containing about 6 × 104 cells per culture well from 2 × 106 of MI-induced SPCs (MI-SPCs). Then, 2·5 × 105 of normal SPCs in 0·2 ml of the medium containing 2 μg/ml Con A were poured onto the resultant Mφ cultures. SPCs were then cultivated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 72 h and pulsed with 0·5 μCi of 3H-TdR (2 Ci/mmol) for the final 6–8 h. Cells were harvested onto glass fibre filters and counted for radioactivity using a 1450 Microbeta Trilux scintillation spectrometer (Wallac Co., Turku, Finland). Suppressor activity of MI-Mφs was calculated as:

|

Cytokine mRNA expression by MI-Mφs

Total RNA was isolated from MI-Mφs (3 × 106) given or not given 24-h precultivation with nylon wool column-purified T cells (5 × 106) were lysed using an Isogen kit (Nippon Gene Co., Toyama, Japan). The amounts of cytokine mRNAs were measured by the RNase protection assay [11] using RiboQuantTM Multi-Probe RNase Protection Assay System (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instruction manual. In this study, a mCK-3 mouse cytokine multi-probe template set was employed for measurement of mRNAs of TNF-α, TNF-β, IFN-γ, lymphotoxin-β and TGF-β.

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity of MI-Mφs

MI-Mφs (7·5 × 106) suspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7·2) were sonicated at medium power for 60 s using a sonicator (Model Bioruptor, Cosmo Bio Co., Tokyo, Japan), centrifuged at 20000 g for 5 min. The protein concentration of the supernatant was adjusted to 0·2 mg/ml and used as a crude enzyme preparation (MI-Mφ cell lysate). The IDO activity of the MI-Mφ cell lysate was measured by the method of Yamamoto et al. [12]. Briefly, the reaction mixture (200 μl) consisting of 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7·5), 50 μm methylene blue, 10 mm ascorbic acid, 120 μl of MI-Mφs cell lysate (24 μg protein) and 3 mmd-tryptophan as a substrate with or without the addition of 600 μm of 1-methyl-l-tryptophan as an IDO inhibitor was incubated at 37C° for 30 min. After stopping the reaction with 1·7% zinc acetate and 0·06 N NaOH, the concentration of kynurenine, a reaction product, was determined in terms of the increase of the absorbance at 360 nm.

Tyrosine (Tyr) phosphorylation of Con A-stimulated T cells

Normal SPCs (4 × 106) were cultivated on a MI-Mφ monolayer (prepared on a 34-mm culture well by seeding 1·5 × 107 MI-SPCs) for 23 h. Non-adherent cells (5 × 106) recovered from the mixed culture were incubated in 1 ml of the medium in the presence of 2 μg/ml of Con A at 37°C for up to 10 min. At intervals, the cell lysate prepared using 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7·4) containing 0·15m NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1 mm Na2VO4 and 1 mm phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) was boiled for 5 min and then subjected to sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blotting was performed using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine MoAb (1 : 5000 dilution) and ECL plus kit, Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA), according to the method of Giacomini et al. [13].

Protein kinase C (PKC) activity of Con A-stimulated T cells

SPCs (1 × 106) were cultivated on a monolayer culture of MI-Mφs (2·5 × 105) prepared on a 16-mm culture well for 12 h, allowing cell-to-cell contact between SPCs and MI-Mφs. The resultant SPCs were stimulated with 20 μg/ml of Con A and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. After the addition of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, non-adherent cells consisting of lymphocytes were harvested by gentle rinsing with 2% FBS-HBSS and subjected to the preparation of cytosolic and membrane-bound PKC according to the method of Kvanta et al. [14]. Briefly, cells were permealized with 0·5 ml of 0·025% digitonin in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7·5) supplemented with 2 mm EDTA, 0·5 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin and 5 mm PMSF, centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant containing cytosolic PKC was removed. The pellet was suspended in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7·5) containing 2 mm EDTA, 0·5 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 mm PMSF and 0·2% Triton X-100. After 10 min centrifugation at 10000 g, the supernatant containing membrane-bound PKC was removed. Both the fractions were dialysed against 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7·5) containing 0·5 mm EDTA, 0·5 mm EGTA, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 0·5 mm PMSF and 0·05% Triton X-100. PKC activity of the resultant enzyme preparations was measured using a PKC assay kit (SignaTECTTM Protein Kinase C Assay System, Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA) and γ-32P] ATP (NEN Life Science Products Inc.) according to the manual provided by the manufacturer.

Expression of PKC isozymes by Con A-stimulated T cells

Splenic T cells (2 × 105) were cultured in the medium (0·2 ml) containing 2 μg/ml of Con A in microculture wells in the presence or absence of MI-Mφs (6 × 104). After 46 h cultivation, the cultured T cells were collected by centrifugation (200 g, 5 min) and smeared onto a glass slide. After formalin fixation, the resultant smears were subjected to staining with MoAbs specific to three PKC isozymes (PKCα, PKCβ, PKCγ) [15] and subsequent colour development using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine•HCl as a substrate by using a MEBPAP C-kinase Isozyme assay kit (MBL Co., Tokyo, Japan). All the procedures were performed according to the manual provided by the manufacturer. The numbers of T cells positive for individual PKC isozymes were counted microscopically.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we usually repeated the same experiments two or three times. Statistical analysis on the data obtained by the representative experiment shown in individual figures and tables was performed using Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Profiles of cell contact in expression of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs

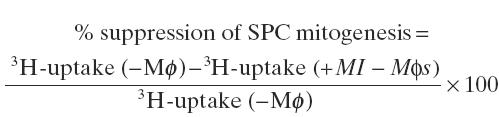

Our previous study, using a dual chamber system, revealed that cell-to-cell contact is needed for efficacious expression of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs against target T cells [10]. The present results shown in Fig. 1 confirm the previous findings. Expression of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs was reduced markedly by separating target T cells from MI-Mφs by a Millipore filter in a dual chamber. In this case, the addition of 5 × 105 of MMC-SPCs to a MI-Mφ monolayer in the ‘bottom chamber', allowing cell-to-cell contact of MI-Mφs with MMC-SPCs, did not potentiate the humoral factor-mediated expression of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs through a Millipore filter. This finding newly indicates that cell contact of MI-Mφs with SPCs did not modulate the production of suppressor mediators such as RNI, FFA, PS, PGE2 and TGF-β [9,10] by MI-Mφs themselves. In separate experiments using the dual chamber system, splenic Mφs induced by M. avium infection were found to express their suppressor activity via cell contact with target T cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Cell-to-cell contact-mediated expression of the suppressor activity of M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs) against Con A-induced T cell mitogenesis. Using a dual-chamber system, spleen cells (SPCs) (5 × 105) were cultured in either the ‘bottom chamber' (BT), on which monolayer cultures of MI-Mφs (3 × 105/well) were prepared (hatched bars) or not prepared (open bars), or the ‘top chamber' (TP) equipped with a 0·45 μm Millipore filter-bottom. In some cases, 5 × 105 of SPCs pretreated with 100 μg/ml mitomycin C for 1 h (MMC-SPCs) were also added to the ‘bottom chamber' (BT). Each bar indicates the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3).

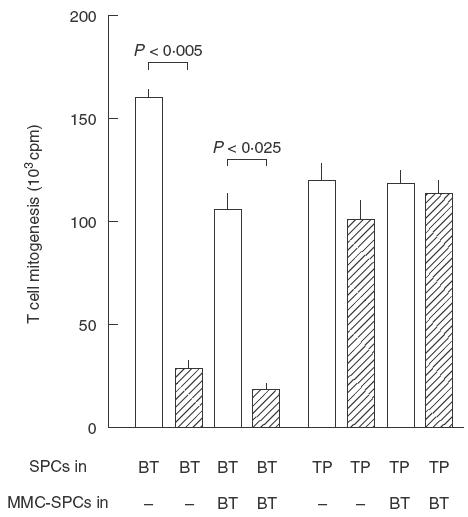

Secondly, we examined expression of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs from BALB/c mice observed when co-cultured with SPCs from syngeneic (BALB/c: H-2d) or allogeneic (C57BL/6 : H-2b; CBA/JN: H-2k) strains of mice. As shown in Fig. 2, MI-Mφs of BALB/c mice also displayed comparable levels of suppressor activity against splenic T cells of allogeneic strains of mice with H-2 alleles different from those of BALB/c mice. Thus, there is no MHC restriction in the expression of the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs against T cells.

Fig. 2.

MHC-unrestricted expression of the suppressor activity by M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs) against target T cells. Con A-stimulated spleen cells (SPCs) (2·5 × 105) from BALB/c (H-2d), C57BL/6 (H-2b) or CBA/JN (H-2k) mice were co-cultured with MI-Mφs (2 × 104/well) from BALB/c mice. Each bar indicates the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4).

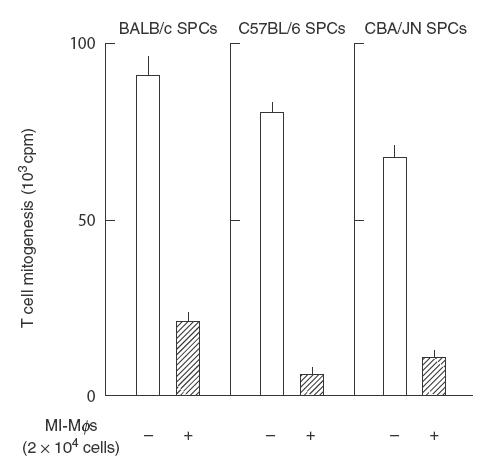

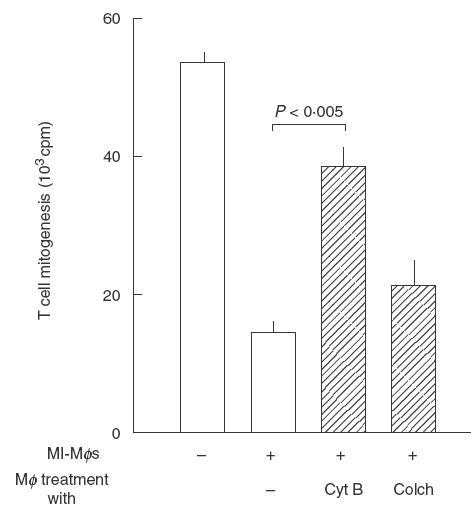

Thirdly, we examined whether MI-Mφs retain suppressor activity even after fixation with paraformaldehyde. As shown in Fig. 3, fixed MI-Mφs exhibited no suppression of Con A-induced T cell mitogenesis, indicating that cell-to-cell contact alone is insufficient for complete transmission of suppressive signals from MI-Mφs to target T cells. In this context, as shown in Fig. 4, it was found that treatment of MI-Mφs with either cytochalasin B (microfilament inhibitor) or colchicine (microtuble inhibitor) attenuated the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs (cytochalasin B-mediated attenuation was significant; P <0·005). This finding indicates that microfilament-dependent and, presumably, microtuble-dependent membrane functions of MI-Mφs play roles in the manifestation of Mφ suppressor activity through cell contact.

Fig. 3.

Deprivation of the suppressor activity from M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs) by paraformaldehyde fixation. MI-Mφs prepared on microculture wells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and measured for their suppressor activity against Con A-induced T cell mitogenesis. Dotted bar: co-cultured with live MI-Mφs. Hatched bar: co-cultivated with fixed MI-Mφs. Each bar indicates the mea± s.e.m. (n = 8).

Fig. 4.

Effects of microfilament and microtuble inhibitors on the suppressor activity of M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs). MI-Mφs (4 × 104) were pretreated with cytochalasin B (CytB) or colchicine (Colch) at 2 μm each for 30 min, washed with 2% FBS-HBSS, and measured for the suppressor activity against Con A-induced T cell mitogenesis. Each bar indicates the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3).

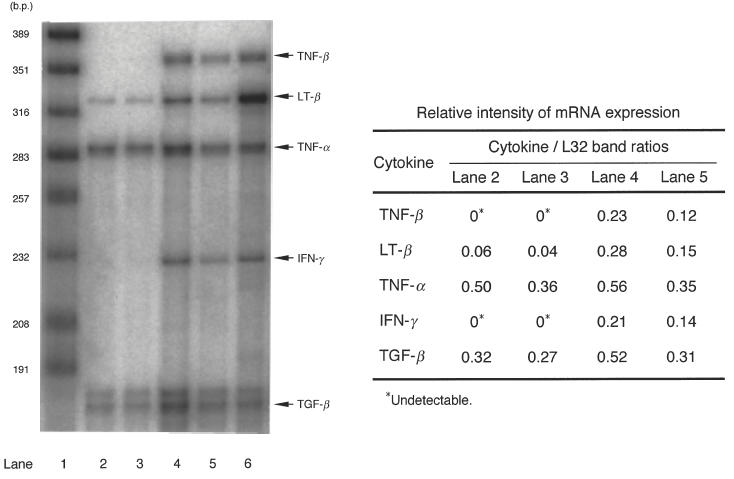

Another possibility remains that sufficient amounts of soluble suppressor mediators released from MI-Mφs only when these Mφs face the target SPCs through cell-to-cell interaction and receive stimulatory signals from the SPCs. In this context, it is known that the binding of CD40 ligand (CD40L) to CD40 molecules on Mφs cause Mφ activation, resulting in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β [16]. Moreover, CD40L/CD40 interaction between Mφs and CD40L-transfected embryonic kidney cells causes the potentiation of Mφ antimycobacterial activity [17]. Therefore, it is possible that the ability of MI-Mφs to produce the suppressor mediators may be up-regulated by CD40L/CD40 interaction. As shown in Fig. 5, when MI-Mφs were co-cultivated with target T cells in the presence of Con A at 37°C for 24 h, mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, TNF-β, lymphotoxin β and IFN-γ) by MI-Mφs was increased. Notably, pretreatment of MI-Mφs with anti-CD40 MoAb (50 μg/ml) decreased their mRNA expression of these cytokines, indicating that the CD40L/CD40 interaction plays important roles in the up-regulation of the expression of these cytokines. However, the pretreatment of MI-Mφs with anti-CD40 MoAb at the same concentration did not affect MI-Mφ-mediated suppression of Con A-induced T cell mitogenesis (data not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs is modulated by CD40L/CD40 interaction.

Fig. 5.

Effects of anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) blocking on cytokine mRNA expression by M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs) with or without cocultivation with T cells in the presence of Con A (2 μg/ml). Levels of mRNA expression of test cytokines were measured by the RNase protection assay. Lane 1, MW marker; lane 2, MI-Mφs; lane 3, anti-CD40 MoAb treated (50 μg/ml at 4°C for 3 h) MI-Mφs; lane 4, MI-Mφs co-cultivated with T cells in the presence of Con A for 24 h; lane 5, MI-Mφs which were pretreated with anti-CD40 MoAb and then co-cultivated with T cells in the presence of Con A for 24 h; lane 6, positive control for each cytokine. The mRNA expression levels of a housekeeping gene (L32) of lanes 2–5 were essentially the same as each other (data not shown). In the right table, relative intensities of cytokine mRNA expression in terms of cytokine/L32 band ratio are indicated.

In this context, a recent study by Munn et al. [18] indicated that Mφs activated with Mφ colony-stimulating factor are able to suppress T cell proliferation via rapid and selective degradation of tryptophan by the enzyme IDO produced by Mφs. This enzyme is induced in Mφs by a synergistic combination of the T cell-derived signals IFN-γ and CD40 ligand. However, 1-methyl-l-tryptophan (IDO inhibitor) did not affect the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs when added at the concentration of 600 μm, although the same dose of the IDO inhibitor caused strong inhibition (73 ± 0·5% inhibition) of the IDO activity in the MI-Mφ cell lysate when added to the reaction mixture. It thus appears that IDO, a novel mediator of suppressor Mφs, does not play an important role in the expression of MI-Mφ suppressor activity.

The mode of suppressor signal transmission between MI-Mφs and target SPCs

We next examined the mode of transmission of suppressive signals from MI-Mφs to target T cells. SPCs were co-cultured with MI-Mφs for 6 or 23 h, and non-adherent cells (lymphocytes) were then transferred to new culture wells and measured for mitogenesis in response to stimulation with either Con A or the combination of PMA with calcium ionophore A23187 (PMA/A23187). As shown in Table 1, 23-h but not 6-h co-cultivation of naive SPCs with MI-Mφs allowing cell-to-cell contact markedly reduced the Con A mitogenic response of the resultant SPCs. On the other hand, 23-h co-cultivation of target SPCs with MI-Mφs caused a slight reduction in their proliferative response to PMA/A23187- induced signalling. As shown in Table 2, 23-h co-cultivation of target SPCs with MI-Mφs also caused marked reduction of SPC mitogenesis induced by anti-CD3 MoAb or the combination of anti-CD3 MoAb with anti-CD28 MoAb. Such a strong suppression was not observed for SPC mitogenesis in response to PMA + A23187, PMA + Con A or A23187 + Con A signalling.

Table 1.

Transmission of suppressive signals from M. intracellulare (MI)-induced macrophages(MI-Mφs) to target T cells via cell-to-cell interaction*

| Precultivation of SPCs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MI-Mφs | Cultivation time | Con A-induced mitogenesis (103cpm ± s.e.m.; n = 3) | PMA/A23187-induced mitogenesis (103cpm ±s.e.m.; n = 3) |

| − | 6h | 67·3 ± 2·3 | 69·5 ± 1·6 |

| + | 6 h | 53·3 ± 4·8 (21%)† | 66·7 ± 4·6 (4%) |

| − | 23 h | 46·7 ± 3·0 | 59·2 ± 2·6 |

| + | 23 h | 5·8 ± 0·7‡ (88%) | 47·3 ± 1·3 (20%)§ |

Spleen cells (SPCs) (4 × 106) were cultivated in 34-mm culture wells with or without the monolayer cultures of MI-Mφs, which were prepared by seeding 1·5 × 107 of MI-induced SPCs at 37°C for indicated time length. The resultant non-adherent cells (lymphocytes) were then transferred to new microculture wells (2 × 105/well), washed with 2% FBS-HBSS and measured for their mitogenesis during 72-h cultivation in response to stimulation with either Con A (2 μg/ml) or the combination of PMA (2nm) with A23187 (0·1mm) (PMA/A23187).

In parenthesis, percent inhibition of mitogenesis due to cell-to-cell interaction with MI-Mφs is indicated.

P <0·01 versus control (−MI-Mφs).

Significantly smaller than the value of MI-Mφ-mediated suppression of Con A-induced mitogenesis (P <0·01).

Table 2.

Differential effects of the cell contact-dependent suppressor signals of M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs) on T cell mitogenesis in response to various stimuli*

| T cell mitogenesis (103cpm ± s.e.m.; n = 3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Triggers for T cell mitogenesis | −MI-Mφs | +MI-Mφs | % Inhibition of mitogenesis |

| − | 0·5 ± 0·1 | 0·7 ± 0·1 | 0 |

| Anti-CD3 MoAb | 36·4 ± 2·2 | 9·4 ± 1·5 | 74 |

| Anti-CD3 MoAb+anti-CD28 MoAb | 47·6 ± 7·3 | 10·1 ± 0·9 | 79 |

| PMA + A23187 | 45·9 ± 0·8 | 41·0 ± 0·6 | 11† |

| PMA + Con A | 60·6 ± 6·7 | 55·6 ± 7·4 | 8† |

| A23187 + Con A | 37·0 ± 0·8 | 36·2 ± 0·9 | 2† |

As described in Table 1, spleen cells (SPCs) were precultivated with or without MI-Mφs for 23 h and the resultant non-adherent cells were then measured for their mitogenesis in response to stimulation with either anti-CD3 MoAb (1 μg/ml, fixed onto culture wells), anti-CD3 MoAb + anti-CD28 MoAb (1 μg/ml each, fixed onto culture wells), PMA + A23187 (2nm and 0·1 μm, respectively), PMA + Con A (2nm and 2 μg/ml, respectively), A23187 + Con A (0·1 μm and 2 μg/ml, respectively).

Significantly smaller than the value of MI-Mφs-mediated suppression of anti-CD3 MoAb-induced mitogenesis (P <0·01).

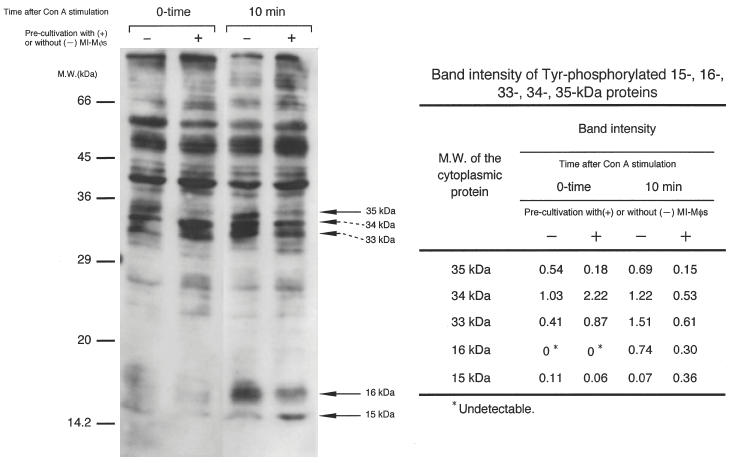

Because these findings suggested that MI-Mφ suppressive signals, which were transmitted to target T cells, interfered with the upstream signalling pathways of PKC activation and/or intracellular calcium mobilization, we examined the profiles of Tyr phosphorylation of cytoplasmic proteins of T cells in the early phase (10 min) after Con A stimulation when the T cells were precultivated with or without cell-to-cell contact with MI-Mφs for 23 h. As shown in Fig. 6, co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs caused significant changes in profiles of the Tyr phosphorylation of some cytoplasmic proteins, as follows. First, Con A stimulation up-regulated Tyr phosphorylation of a 16-kDa protein and co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs markedly suppressed this phenomenon. Secondly, the Tyr phosphorylation of a 15-kDa protein induced by Con A stimulation was observed for T cells which had been co-cultivated with MI-Mφs but not for the control T cells precultivated without cell contact with MI-Mφs. Thirdly, co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs markedly down-regulated the spontaneous Tyr phosphorylation of a 35-kDa protein in the resting stage prior to Con A stimulation. In addition, in the case of T cells co-cultivated with MI-Mφs, the degree of Tyr phosphorylation of this protein was slightly decreased after Con A stimulation, while that in the control T cells was increased to some extent after Con A stimulation. Fourthly, the levels of spontaneous Tyr phosphorylation of 33-kDa and 34-kDa proteins of T cells in the resting stage before Con A stimulation were increased strongly due to co-cultivation with MI-Mφs. Notably, in the case of T cells co-cultivated with MI-Mφs, the levels of Tyr phosphorylation of the 33-kDa and 34-kDa proteins were more or less decreased after Con A stimulation whereas, conversely, the Tyr phosphorylation of these proteins in the control T cells was up-regulated.

Fig. 6.

Profiles of Con A signal-associated tyrosine phosphorylation of cytoplasmic proteins in T cells co-cultivated with M. intracellulare-induced macrophages (MI-Mφs). The splenic lymphocytes which had been precultivated with or without MI-Mφs for 23 h were cultivated for 10 min after Con A stimulation, and then cytoplasmic proteins were extracted as mentioned in the Method section. The cell lysate preparation containing cytoplasmic proteins (35 μg each) was subjected to sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Western blotting using antiphosphotyrosine antibody. In control experiments, the SDS-PAGE patterns of cytoplasmic proteins extracted from splenic T cells with or without co-cultivation with MI-Mφs were the same as each other, indicating that the profile of protein expression by T cells was not altered due to cell contact with MI-Mφs (data not shown). In the right table, the band intensities of the 15-kDa, 16-kDa, 33-kDa, 34-kDa and 35-kDa proteins measured using a densitometer are indicated.

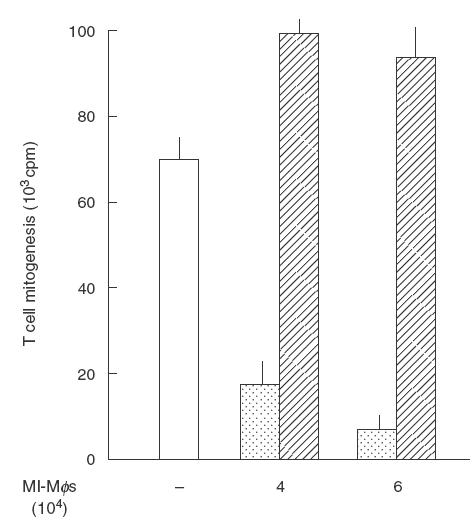

Next, we examined the effect of MI-Mφs upon PKC activation and the translocation of PKC from the cytoplasm to cell membrane in Con A-stimulated T cells. SPCs were co-cultured for 12 h with MI-Mφs allowing cell-to-cell contact, then given Con A stimulation, and incubated for 10 min allowing cell contact with MI-Mφs. Then, Mφ-depleted cells were subjected to the measurement of membranous and cytosolic PKC activities. As shown in Table 3, a marked reduction of the Con A-induced PKC activation and translocation to cell membrane was observed when the SPCs had been co-cultivated with MI-Mφs. This finding supports the above concept that MI-Mφ-mediated suppressor signals interfere principally with the upstream pathways of PKC activation and translocation.

Table 3.

Inhibition of Con A-induced protein kinase C (PKC) activation and translocation to the cell membrane of splenic T cells due to cell-to-cell contact with M. intracellulare-induced macrophages(MI-Mφs)*

| PKC activity (pmoles/min/μg protein)† | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-cultivation with MI-Mφs | Con A-stimulation | Cytosolic PKC | Membrane-bound PKC |

| − | − | 23·9 ± 1·4 | 12·9 ± 2·1 |

| − | + | 70·4 ± 1·0 | 22·5 ± 0·4 |

| + | − | 26·5 ± 2·0 | 6·49 ± 0·70 |

| + | + | 33·9 ± 3·9‡ | 3·70 ± 0·58 |

SPCs (1 × 106) were cultivated on a monolayer culture of MI-Mφs (2·5 × 105) prepared on a 16-mm culture well for 12 h, and then 20 μg/ml of Con A was added. After 10 min incubation at 37°C, non-adherent cells (lymphocytes) were harvested and measured for activity of cytosolic and membrane-bound PKC (see Materials and methods).

Mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3).

P <0·01 versus controls (Con A-stimulated T cells without co-cultivation with MI-Mφs).

In this context not only PKCθ, a novel PKC isozyme, which is known to play central roles in T cell activation via JNK/SAPK signalling [19,20], but also PKCα and PKCβ play important roles in T cell-signalling pathways causing its activation [21,22]. Thus, we examined the effects of MI-Mφs on the expression of PKCα and PKCβ in Con A-stimulated T cells. Immunocytochemical studies using anti-PKCα, anti-PKCβ and anti-PKCγ MoAbs revealed that MI-Mφs reduced the expression of PKCα and PKCβ in Con A-stimulated T cells. The values of % positive cells for PKCα, PKCβ and PKCγ in resting splenic T cells before Con A stimulation were 26 ± 5, 6 ± 1 and 1 ± 1%, respectively. These values were increased to 41 ± 4, 42 ± 5 and 23 ± 6%, respectively, at 46 h after Con A-stimulation. When Con A-stimulated T cells were co-cultured with MI-Mφs, the values of % positive cells of PKCα, PKCβ and PKCγ were 35 ± 1, 25 ± 3 and 26 ± 4%, respectively. Thus, MI-Mφs reduced the expression of PKCα and PKCβ but not of PKCγ in Con A-stimulated T cells.

In separate experiments, the cAMP-elevating agents NaF (1 mm) [23] and PGE2 (10 μm) [24] markedly decreased Con A-induced mitogenic responses of SPCs, with inhibitions of 91 ± 10 and 85 ± 4%, respectively. However, the reduction of cAMP levels in SPCs due to somatostatin, an adenylate cyclase inhibitor, did not interfere significantly with suppression by MI-Mφs of SPC mitogenesis: MI-Mφs (2 × 104) suppressed Con A mitogenic response of SPCs with or without treatment with somatostatin (0·25 μm) at an inhibition ratio of 98 ± 4 and 98 ± 2%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the case of MI-Mφs, cell-to-cell contact is required for Mφ-mediated suppression of T cell mitogenesis, in addition to Mφ-derived soluble suppressor molecules such as RNI, FFA, PS, PGE, and TGF-β [8–10]. Because MI-Mφs displayed suppressor activity in an H-2 allele-independent manner, it appears that MHC molecules are not required for such cell contact. Fixation of MI-Mφs with paraformaldehyde diminished their suppressor activity, although the fixed MI-Mφs retained their ability to bind with splenic lymphocytes: live MI-Mφs, 2·57 ± 0·26 cells/Mφ; fixed MI-Mφs, 2·27 ± 0·24 cells/Mφ (unpublished observation). In addition, cytochalasin B strongly attenuated the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs, suggesting that microfilament-dependent membrane function and movement may be required for cell-to-cell interactions of MI-Mφs with target T cells. These findings imply that vital membrane functions, particularly actin filament-mediated membrane functions, which are known to play roles in the formation of focal adhesion and stress fibres [25], are required for the suppressor activity of MI-Mφs.

It is known that Con A binds the CD3 component of the T cell receptor (TCR) and shares most stimulatory properties of anti-CD3 or anti-TCR MoAbs [26]. As indicated in Tables 1 and 2, when MI-Mφ-derived suppressive signals were transmitted to resting T cells in which TCR-coupled signalling pathways were in the resting state via cell-to-cell contact during 23-h co-cultivation and the resultant T cells were then stimulated with either Con A, anti-CD3 MoAb, or the combination of anti-CD3 MoAb with anti-CD28 MoAb, T cell mitogenesis in response to Con A signals was potently inhibited. In contrast, T cell mitogenesis induced by either PMA + A23187, PMA + Con A or A23187 + Con A signalling was not suppressed, even after 23 h co-cultivation with MI-Mφs. These findings suggest that suppressive signals, which are transmitted from MI-Mφs to resting T cells via cell-to-cell contact, interfere with the signalling cascades of T cell activation that occur upstream of PKC activation and/or intracellular calcium mobilization, such as the pathways consisting of ZAP-70, LAT and phospholipase C-γ 1 or ZAP-70, LAT, Shc, Grb2 and Sos [27–29]. This concept is supported by the findings that co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs allowing cell contact caused marked changes in profiles of the Tyr phosphorylation of some cytoplasmic proteins (Fig. 6) and, moreover, PKC activation and its translocation to cell membrane (Table 3).

As shown in Fig. 6, co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs caused marked changes in the profiles of Tyr phosphorylation of some cytoplasmic proteins of target T cells, including the 15-kDa, 16-kDa, 33-kDa, 34-kDa and 35-kDa proteins after Con A stimulation and, in some cases, before Con A stimulation. It thus appears that these proteins may play the roles in a cross-talk of MI-Mφ-derived suppressor signals with the early signalling pathways of Con A-stimulated T cells. Since co-cultivation of T cells with MI-Mφs markedly up-regulated the spontaneous Tyr phosphorylation of the 33-kDa and 34-kDa proteins before Con A stimulation, it is possible that these proteins may play roles as the portal of the entry of MI-Mφ-derived suppressive signals into T cells.

Although these proteins have not yet been identified, the following can be stated. First, these five proteins are distinguished from Fyn, Lck, ZAP-70, Vav, Hsl, Cbl, SLP-76, Grb-2, SOS and PI3 k, which are known to play roles in the early stages of TCR signalling [27–29] on the basis of their molecular weights. Similarly, on the basis of molecular weight, the 33-kDa and 34-kDa proteins are also distinguished from Csk and SHP-1, both of which suppress TCR signalling pathways via inhibition of Fyn and Lck [27–29]. Secondly, the 16-kDa protein may correspond to LMPTP-C, a novel isoform of the low molecular weight phosphotyrosine phosphatase [30] or a TCR-associated protein (TRAP)-related protein [31], although no evidence has been reported that these two proteins are Tyr-phosphorylated. Thirdly, the 35-kDa protein may correspond to HAX-1 protein, which is directly associated with HS1, a substrate of Src family and Syk/ZAP-70 Tyr kinases that play important roles in the early events of TCR-mediated signalling in T cells [32]. The 35-kDa protein may also correspond to a protein which is phosphorylated by a CD8 coupled protein-Tyr kinase p56lck [33]. This is, to our knowledge, the first observation of cross-talk of Mφ-mediated suppressor signals, which are transmitted to target T cells via cell-to-cell contact, with TCR-associated signalling pathways, thereby causing the inhibition of Tyr phosphorylation of certain proteins.

Finally, the reduction of cAMP levels in target T cells did not affect the efficacy of MI-Mφ-mediated suppression of Con A-induced T cell mitogenesis. It is thus unlikely that the suppressive signals from MI-Mφs cross-talk with the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase or its downstream events hindering T cell activation processes, such as inhibition of TCR ligation-coupled Lck autophosphorylation and intervention at the activation of ERK and JNK [34]. Further studies are currently under way to examine in detail the profiles of cross-talk of suppressive signals from MI-Mφs with T cell signalling pathways, including identification of the 15-kDa, 16-kDa, 33-kDa, 34-kDa and 35-kDa proteins of T cells, Tyr-phosphorylation profiles of which were significantly modified due to cell-to-cell contact with MI-Mφs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ellner JJ. Suppressor adherent cells in human tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1978;121:2573–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards CK, Hedegaar HB, Zlotnik A, et al. Chronic infection due to Mycobacterium intracellulare in mice: association with macrophage release of prostaglandin E2 and reversal by injection of indomethacin, muramyl dipeptide, and interferon-γ. J Immunol. 1986;136:1820–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomioka H. Immunosuppressive macrophages. Clin Immunol. 2000;33:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomioka H, Saito H, Yamada Y. Characteristics of immunosuppressive macrophages induced in spleen cells by Mycobacterium avium complex infections in mice. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:965–74. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-5-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomioka H, Saito H, Sato K. Characteristics of immunosuppressive macrophages induced in host spleen cells by Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:283–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomioka H, Saito H. Characterization of immunosuppressive functions of murine peritoneal macrophages induced with various agents. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:24–31. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomioka H, Maw WW, Sato K, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor-α in combination with interferon-γ or interleukin-1 in the induction of immunosuppressive macrophages because of Mycobacterium avium complex infection. Immunology. 1996;88:61–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomioka H, Sato K, Maw WW, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor, interferon-γ, transforming growth factor-β, and nitric oxide in the expression of immunosuppressive functions of macrophages induced by Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:704–12. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.6.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomioka H, Kishimoto T, Maw WW. Phospholipids and reactive nitrogen intermediates collaborate in expression of the T cell mitogenesis-inhibitory activity of immunosuppressive macrophages induced in mycobacterial infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:219–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maw WW, Shimizu T, Tomioka H, et al. Further study on the roles of the effector molecules on immunosuppressive macrophages induced by mycobacterial infection in expression of their suppressor function against mitogen-stimulated T cell proliferation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:26–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fixman ED, Fournier TM, Kamikura DM, et al. Pathways downstream of Shc and Grb2 are required for cell transformation by the Tpr-Met oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13116–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto S, Hayaishi O. Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (Tryptophan pyrrolase) In: Colowick SP, Kaplan NO, editors. Methods in enzymology. XVII. New York: Academic Press; 1970. pp. 434–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giacomini E, Iona E, Ferroni L, et al. Infection of human macrophages and dendritic cells with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a differential cytokine gene expression that modulates T cell response. J Immunol. 2001;166:7033–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kvanta A, Jondal M, Fredholm BB. Translocation of the α- and β- isoforms of protein kinase C following activation of human T-lymphocytes. FEBS Lett. 1991;283:321–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80618-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidaka H, Tanaka T, Onoda K, et al. Cell type-specific expression of protein kinase C isozymes in the rabbit cerebellum. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4523–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuroiwa T, Lee FG, Danning CL, et al. CD40 ligand-activated human monocytes amplify glomerular inflammatory responses through soluble and cell-to-cell contact-dependent mechanisms. J Immunol. 1999;163:2168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi T, Rao SP, Meylan PR, et al. Role of CD40 ligand in Mycobacterium avium infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3558–65. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3558-3565.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, et al. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1363–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monks CR, Kupfer H, Tamir I, et al. Selective modulation of protein kinase C-theta during T-cell activation. Nature. 1997;385:83–6. doi: 10.1038/385083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villalba M, Courdronniere N, Deckert M, et al. A novel functional interaction between Vav and PKCθ is required for TCR-induced T cell activation. Immunity. 2000;12:151–60. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggaewal S, Lee S, Mathur A, et al. 12-Deoxyphorbol-13-O-phenylacetate 20 acetate [an agonist of protein kinase C beta (PKC β1)] induces DNA synthesis, interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, IL-2 receptor alpha-chain (CD25) and beta chain (CD122) expression, and translocation of PKC beta isozyme in human peripheral blood lymphocytes: evidence for a role of PKC beta in human T cell activation. J Clin Immunol. 1994;14:248–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01552311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Lago MA, Freire-Moar J, Barja P. Inhibition of protein kinase C alpha expression by antisense RNA in transfected Jurkat cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:466–76. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<466::AID-IMMU466>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckner SK, Farrar WL. Potentiation of lymphokine-activated killer cell differentiation and lymphocyte proliferation by stimulation of protein kinase C or inhibition of adenylate cyclase. J Immunol. 1988;140:208–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aussel C, Mary D, Peyron J, et al. Inhibition and activation of interleukin 2 synthesis by direct modification of guanosine triphosphate-binding proteins. J Immunol. 1988;140:215–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huttenlocher A, Sandborg RR, Hoewitz AF. Adhesion in cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:697–706. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chilson OP, Kelly-Chilson AE. Mitogenic lectins bind to the antigen receptor on human lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1988;19:389–96. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clements JL, Boerth NJ, Lee JR, et al. Integration of T cell receptor-dependent signaling pathways by adaptor proteins. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:89–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Germain RN, Stefanova I. The dynamics of T cell receptor signaling: complex orchestration and the key roles of tempo and cooperation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:467–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latour S, Veillette A. Proximal protein tyrosine kinases in immunoreceptor signaling. Cur Opin Immunol. 2001;13:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tailor P, Gilman J, Williams S, et al. A novel isoform of the low molecular weight phosphotyrosine phosphatase, LMPTP-C, arising from alternative mRNA splicing. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:277–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antusch D, Bonifacino JS, Burgess WH, et al. The T cell receptor-associated protein is proteolytically cleaved in a pre-Golgi compartment. J Immunol. 1990;145:885–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki Y, Demoliere C, Kitamura D, et al. HAX-1; a novel intracellular protein, localized on mitochondria, directly associates with HS1, a substrate of Src family tyrosine kinases. J Immunol. 1997;158:2736–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barber EK, Dasgupta JD, Schlossman SF, et al. THe CD4 and CD8 antigens are coupled to a protein-tyrosine kinase (p56lck) that phosphorylates the CD3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3277–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamir A, Granot Y, Isakov N. Inhibition of T lymphocyte activation by cAMP associated with down-regulation of two parallel mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, the extracellular signal-related kinase and c-jun N-terminal kinase. J Immunol. 1996;157:1514–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]