Abstract

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a major regulatory cytokine of inflammatory responses that is considered to play an important role in specific immunotherapy. However, whether IL-10 enhances or inhibits B-cell IgE production has remained a matter of contention. To clarify the effect of IL-10 on IgE synthesis in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 signalling, we examined B-cell proliferation, germline ɛ transcripts and plasma cell differentiation. In addition, the effect of CD27 signalling on IgE synthesis in the presence of IL-10, IL-4 and CD40 signalling was investigated. IL-10 facilitated the production of IgE in mononuclear cells and highly purified B-cells, enhanced B-cell proliferation and, most importantly, promoted the generation of plasma cells. However, IL-10 did not enhance expression of germline ɛ transcripts. The addition of CD27 signalling through the use of CD32–CD27 ligand (CD70) double transfectants significantly diminished the B-cell proliferation, IgE synthesis and plasma cell differentiation enhanced by IL-10. IL-10 enhances B-cell IgE production by promoting differentiation into plasma cells. CD27/CD70 interactions under IL-10 and sufficient CD40 cosignalling exert the opposite effect on IgE synthesis. The results of this study indicate that precautions are critical when planning immunotherapy using IL-10 in IgE-related allergic diseases.

Keywords: IL-10, IgE, plasma cell, B cell, CD27

INTRODUCTION

Allergen-specific IgE plays a key role in the physiopathology of allergic disorders. The processes of IgE production by B cells are involved in germline ɛ transcript expression, IgE class switching, clonal expansion of B-cells, and differentiation into IgE-secreting plasma cells. All of these activities are controlled by a variety of cytokines and direct cell-to-cell contact between B cells and helper T cells [1–4]. IL-4, in addition to IL-13, is an important cytokine for promoting the expression of germline ɛ transcripts [5–7]. CD40 is a member of the TNF receptor family and its ligand CD154 is a reciprocal TNF-related ligand. Stimulation of CD40 is also necessary for IgE synthesis and probably for inducing switch recombinases or some proteins associated with switch recombinases [8,9]. CD40 signalling added to IL-4 induces mature ɛ transcripts and IgE is subsequently produced in vitro[3,10,11]. Several other regulatory molecules may also be involved in the regulation of B-cell IgE secretion [12–16].

IL-10 is a major regulatory cytokine involved in inflammatory responses. It is a general inhibitor of proliferation and cytokine responses in T-cells, and is considered to play a key role in specific immunotherapy [17]. The effect of IL-10 on the stimulation of IgA and IgG secretion from Staphylococus aureus Cowan strain- (SAC-) and CD40-activated human B cells is synergistic [18,19]. However, the functions of IL-10 in B-cell IgE synthesis are still under debate. The addition of IL-10 to purified B cells activated by soluble CD154 and IL-4 inhibits IgE synthesis [17]. Other evidence indicates that IL-10 promotes IgE synthesis in the presence of IL-4 and anti-CD40 moAb cross-linked with CD32-transfectants (CD40 moAb/CD32T) [18,20].

To clarify the functions of IL-10 in B-cell IgE synthesis, the present study investigated the effects of IL-10 on B-cell proliferation, expression of germline ɛ transcripts and differentiation into plasma cells. In addition, we examined the role of the CD27/CD70 interactions that play a crucial role in the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells, using an IgE-synthesis system in co-operation with IL-10.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

We purchased FITC-conjugated anti-CD20 moAb and PE- conjugated anti-CD20 moAb from DAKO Japan (Tokyo, Japan) and FITC-conjugated anti-CD38 moAb (T16; IgG1), anti-CD27 moAb (1A4; IgG1) (CD27 moAb) and anti-CD70 moAb (HNE51; IgG1) from Immunotech-Coulter (Marseille, France). Anti-CD40 moAb (G28-5; IgG1) (CD40 moAb) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Human IL-4 and IL-10 were obtained from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Cell preparation

Human adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from volunteers, having no history of allergic disorders (asthma, atopic dermatitis and/or perennial rhinitis) and whose serum IgE levels were less than 300 U/ml, after informed consent. PBMC were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA) density gradient centrifugation and separated with 5% sheep erythrocytes into erythrocyte rosette-positive and negative (E−) populations [21]. The positive selection of B cells was as described [22]. Briefly, monocytes were depleted with silica (IBL, Fujioka, Japan) or by adherence to a plastic surface, then E− cells were separated into B cells by positive selection with anti-CD19 moAb-coated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). Anti-CD19 moAb was removed using Detach-a-Bead (Dynal). B-cell proliferation was confirmed as negative in 97% of the population, which reacted with anti-CD20 moAb. No activation was evident in these B cells. The negative selection of B cells was also performed by using RosetteSep – human B cell cocktail (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), which included anti-CD2, CD3, CD16, CD36 and CD56 moAb. Whole blood was incubated with RosetteSep-human B cell for 20 min at room temperature and centrifuged over Ficoll-Hypaque. The cells at the interface were washed twice with PBS. The B-cell purity thus selected was 80 ± 5%.

Preparation and fixation of transfectants

CD32- (Fcγ II receptor-) transfectants (CD32T) were prepared by conventional methods. Total RNA was isolated by the single-step method [23] from the CD32+ human monocytic cell line U937. Primers used to generated a full-length CD32 cDNA were: sense primer, 5′-TAGTCGACAGTGCTGGGATGAC-3′ (including a SalI cloning site); and antisense, 5′-TAGCGGCCG CTACGCAAGCTGAGAGTA-3′ (including a NotI cloning site). The cDNA amplified by RT-PCR was ligated with the mammalian expression vector BCMGhyg[24]. The resulting plasmid or vector alone was transfected into the murine pre-B-cell line, 300–19 [25], by electroporation. CD32T were selected by growth in culture medium with 1 mg/ml of hygromycin B (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). We also constructed CD70-transfectants (CD70T) and the CD32–CD70 double transfectants (CD32– CD70T). Total RNA was isolated from a CD70− human B-cell line (Daudi cells). CD70 cDNA was isolated by RT-PCR using full-length CD70 cDNA primers: sense primer, 5′-TCAGTCG ACTCTCGGCAGCGCTCC-3′ (including a SalI cloning site); and antisense, 5′-TCGAGCGGCCGCCCTAATCAGCAG- 3′ (including a NotI cloning site), and inserted into the mammalian expression vector BCMGneo, and the resulting plasmid was transfected by electroporation into the 300–19 cell line or CD32T. Both transfectants were selected by growth in medium containing 1 mg/ml of the neomycin analogue G418 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). Cell lines expressing high levels of CD32, CD70 or CD32–CD70 were selected by monitoring CD32 and CD70 expression from colonies using flow cytometry. Transfected cells were then incubated with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min. After three washes with PBS, the cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 30 min, then analysed.

Flow cytometry

Activated purified peripheral blood (PB) B cells were stained with anti-CD38-FITC and anti-CD20-PE. Two-colour analysis of B-cell surface molecules was performed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA). Ab-coated cells were gated on viable cells by cell size and granularity. Dead cells were removed by propidium iodide (PI) staining. Remaining viable cells were then enumerated by flow cytometric analysis.

B-cell proliferation and IgE assays

Purified PB B-cells or PBMC were cultured with medium in 96-well round-bottom plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark), and stimulated with 50 ng/ml of IL-4, 50 ng/ml each of IL-10 and IL-4 plus 1 μg/ml of CD40 moAb in the presence of fixed CD32T (20% of the B-cell numbers added) with or without IL-10 at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The final cell density was 5–10 × 105 cells/ml in a volume of 200 μl/well. For other analyses, highly purified B-cells were cultured in the presence of IL-4, IL-10 and CD40 moAb with CD32T, CD32–CD70T (20% of the B-cell numbers added), CD32T + CD70T (20% of the B-cell numbers added) or CD32T + CD27 moAb with or without anti-CD70 blocking moAb under the same conditions. 20% of the B-cell numbers of each transfectants was added. After a 3-day incubation, the purified B-cells were pulsed with 0·5 μCi 3H]thymidine for 18h and harvested with an automatic cell harvester (Packard, Meriden, CT, USA). Radioactive incorporation was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (Packard). Cultured supernatants of MNCs and purified B-cells were harvested on days 12–14 for IgE assays, then the supernatants were added to 96-well flat ELISA plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The plates were coated with anti-human IgE moAbs (CIA-E-7·12 and CIA-E-4·15, provided by Dr A. Saxon, Division of Clinical Immunology/ Allergy, University of California, School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA, USA). After overnight incubation at 4°C, the supernatants were discarded and the wells were washed with 0·05% Tween 20 in PBS. Alkaline phosphatase-labelled goat anti-human IgE (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added at a dilution of 1/5000. After 2h incubation at room temperature, colour was detected in 3-cyclohexylamino]-1-propanesulphonic acid (CAPS) buffer containing p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) (Sigma). The optical density was determined with an automated ELISA plate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). The standard curves were constructed using serial 1/2 dilutions of standard human IgE (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) from 500 ng/ml to 8 ng/ml. The limit of detection sensitivity for IgE was 5 ng/ml.

Germline ɛ transcript expression

Purified PB B cells (2 × 106) were stimulated with medium, 50 ng/ml of IL-4 or IL-4 plus 1 μg/ml of CD40 moAb in the presence of CD32T with or without IL-10 50 ng/ml for 16 h. Total RNA was extracted with acid-guanidine thiocyanate-phenol- chloroform using a TRIzol rapid RNA purification kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). First-strand cDNA copies were synthesized using murine Moloney leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) with oligo (dT) (Life Technologies) as the primer in a total volume of 20 μl. Two microlitres of cDNA were amplified by PCR using each primer and Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies). Amplified products were resolved on a 1·2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized by ultraviolet light illumination. Quantitative real-time PCR was also performed using a LightCycler (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). The RT reaction (2 μl) was amplified in a final volume of 20 μl, containing 2 μl of Master SYBR Green I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), 0·16 μl of Taqstart Antibody (CLONTECH Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and 3 mm magnesium chloride. A standard curve was generated using diluted RT reaction mixtures obtained from PB B-cells stimulated with IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T. The following oligonucleotide primers were used for PCR and quantitative real-time PCR: the Cɛ primer, 5′-ACGGAGGTGGCATTGG AGGGAATGT-3′, and a primer based on a region located in the germline exon, 5′-AGGCTCCACTGCCCGGCACAGAAAT-3′[6].

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using the t-test or paired t-test.

RESULTS

Effect of IL-10 on IgE synthesis

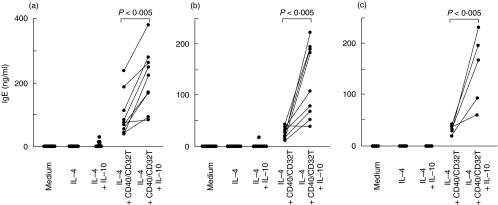

We first investigated the effects of IL-10 on B cell IgE synthesis by human PBMC or highly purified PB B cells. PBMC obtained from healthy individuals did not secrete detectable levels of IgE in the presence of medium alone, IL-4 or IL-4 + IL-10, but produced substantial amounts of IgE in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T. IL-10 considerably augmented IgE production as compared with IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T (P < 0·005, paired t-test, n = 9) (Fig. 1a). To exclude the effect of contaminating T-cells and monocytes, we purified PB B cells by positive selection and examined IgE synthesis. Similarly to PBMC, B cells purified by positive selection cultured in the presence of medium alone, IL-4 or IL-4 + IL-10 did not produce IgE, but did produce IgE in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T. IL-10 in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T also markedly enhanced the amount of IgE produced by positive selected B cells (P < 0·005, paired t-test, n = 9) (Fig. 1b). Similar results were observed by using B cells purified by negative selection (P < 0·005, paired t-test, n = 5) (Fig. 1c). Purified B cells appeared to produce a less amount of IgE than PBMC in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T with or without IL-10. These data demonstrate that IL-10 induces IgE synthesis by PBMC and purified B cells activated with IL-4 and CD40 signalling.

Fig. 1.

Enhancement of IgE synthesis by IL-10. (a) PBMC (n = 9), (b) PB B cells obtained by positive selection (n = 9) and (c) PB B cells obtained by negative selection (n = 5) were cultured with medium alone, IL-4 or IL-4 plus CD40 moAb plus CD32T with or without IL-10 at a final cell density of 1–2 × 105/well in 96-well round-bottom plates. After 12–14 days, supernatants were harvested and IgE content was measured by ELISA. PBMC and purified B cells by positive selection were obtained from same blood samples. Lines drawn between points show that data were derived from cells from a single individual. Statistics were performed using the paired t-test.

Effect of IL-10 on B-cell proliferation

We next assessed the effects of IL-10 on the B-cell proliferation in the presence of various stimuli involved in IgE synthesis. Table 1 shows that IL-4 induced B-cell proliferation, but this proliferation was then diminished by the addition of IL-10. CD40 signalling by CD40 moAb/CD32T markedly enhanced IL-4 induced B-cell proliferation. The addition of IL-10 further augmented the proliferative effects (Table 1). These findings indicate that although IL-10 diminished the B-cell proliferation activated by IL-4, IL-10 promoted B-cell proliferation under the combined stimuli of IL-4 and CD40 together.

Table 1.

Effect of IL-10 on B-cell proliferation

| [3H] thymidine incorporation (cpm) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | |

| Medium | 117 ± 55 | 220 ± 42 |

| IL-10* | 177 ± 38 | 187 ± 53 |

| IL-4* | 822 ± 118 | 1344 ± 48 |

| IL-4 + IL-10 | 483 ± 18 | 840 ± 47 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb*/CD32T† | 27889 ± 4180 | 23467 ± 3355 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T + IL-10 | 36393 ± 1799‡ | 32633 ± 2462‡ |

IL-4, IL-10 and CD40 moAb were each added at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml, 50 ng/ml and 1 μg/ml.

Transfectants were present as 20% of the B-cell numbers added.

P <0·05 compared with IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T. Statistical analyses were performed by t-test

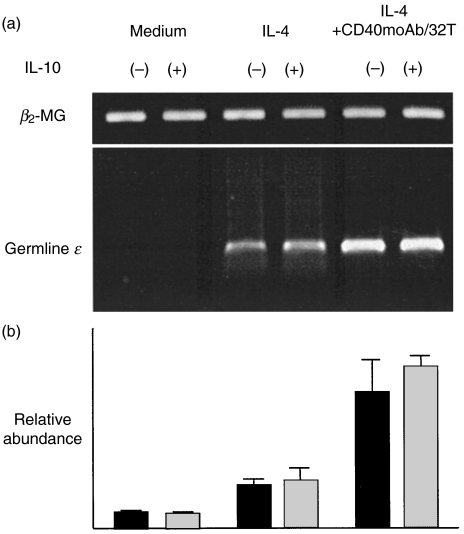

Effect of IL-10 on expression of germline ɛ transcripts

The induction of germline ɛ transcripts is an early process in IgE synthesis and is necessary for IgE production. We therefore investigated whether or not IL-10 promotes the induction of germline ɛ transcripts. Germline ɛ transcripts were undetectable in highly purified PB B cells cultured with medium or IL-10 alone. However, these transcripts were induced by IL-4 and were not thereafter affected by IL-10, but were enhanced by CD40 moAb/CD32T (Fig. 2). The germline ɛ expression induced by IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T was unaffected by the addition of IL-10 (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that the enhancement of IgE production by IL-10 does not depend on the induction of germline ɛ transcripts.

Fig. 2.

Germline ɛ transcript expression by highly purified PB B cells. B cells were stimulated with medium alone, IL-10, IL-4, IL-4 + IL-10 or IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T with or without IL-10. (a) Germline ɛ transcript expression was determined using RT-PCR. (b) Quantification by real-time RT-PCR of the data shown in A proceeded as described in Materials and Methods. Each template contained the same amount of RNA extracted from 2 × 106 highly purified PB B cells. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Generation of plasma cells by IL-10

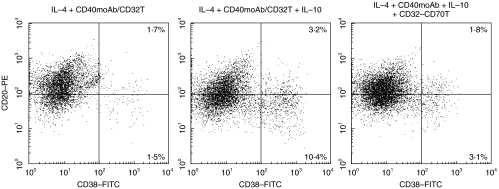

Since the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells is crucial to IgE production, we studied the effects of IL-10 on PB B-cell differentiation in the presence of IL-4 with CD40 signalling. Human PB B cells expressed high levels of CD20 and CD40 and a low level of CD38. After differentiation into plasma cells, they expressed high levels of CD38 and diminished expression of CD20. Interestingly, B cells stimulated with IL-10 in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T for 12–14 days differentiated into plasma cells. In contrast, IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T without IL-10 induced slight increase in the number of plasma cells (Fig. 3). Morphological analysis revealed these CD20−CD38high cells were typical plasma cells, displaying basophilic cytoplasm with a pale Golgi zone and an eccentric nucleus (data not shown). Moreover, flow cytometry analyses of intracellular immunoglobulins (Igs) in the CD20−CD38high cells revealed a high expression of Igs (data not shown). These results demonstrated that IL-10 promotes the generation of plasma cells in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 signalling.

Fig. 3.

Effect of IL-10 and CD27 signalling on plasma cells differentiation in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T. Highly purified PB B cells were cultured with IL-4 plus CD40 moAb in the presence or absence of IL-10, CD32T or CD32–70T for 12–14 days. Cells were then stained with anti-CD38-FITC and anti-CD20-PE. Ab-coated cells were gated on living cells according to size and granularity, then dead cells were removed by propidium iodide staining. Remaining cells were enumerated by flow cytometry. Expression of CD38 and CD20 on B cells is shown with log scale.

Effect of CD27 signalling on IgE production

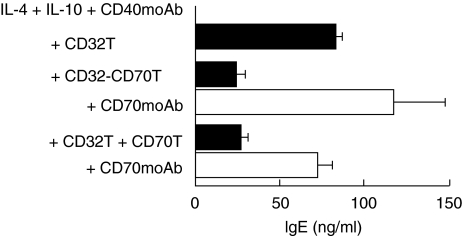

We demonstrated that CD27 signalling enhances IgE synthesis by promoting B-cell differentiation into plasma cells under IL-4 and CD40 moAb stimulus [22]. Accordingly, we investigated the effect of CD27 signalling on IgE production in the presence of IL-4, CD40 moAb/CD32T and IL-10. As reported previously [22], addition of CD70T enhanced B-cell IgE production in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb without CD32T (Table 2). In the presence of a mixture of IL-4 + IL-10 + CD40 moAb, IgE production was decreased in B cells by CD32–CD70T as compared with CD32T. Similar results were obtained with mixtures of CD32T + CD70T or CD32T + CD27 moAb (Table 2). The inhibition of IgE synthesis via CD27 by CD32–CD70T or CD32T and CD70T was restored by the addition of anti-CD70 blocking moAb (Fig. 4)

Table 2.

IgE synthesis and B-cell proliferation by CD27 signalling in the presence of IL-10

| IgE (ng/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | [3H]thymidine incorporation (cpm) | |

| Medium | ≤8 | ≤8 | 426 ± 155 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb* | ≤8 | 30 ± 12 | 2560 ± 605 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb*+ CD70T† | 43 ± 10 | 65 ± 14 | 5044 ± 678 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T‡ | 14 ± 12 | 43 ± 13 | 17042 ± 3907 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T + IL-10* | 183 ± 13 | 159 ± 18 | 51547 ± 2346 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb + CD70: CD32T† + IL-10 | 21 ± 15 | 65 ± 14 | 26758 ± 2346 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T + CD27 moAb* + IL-10 | 73 ± 23 | 60 ± 14 | 39565 ± 5605 |

| IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T + CD70T + IL-10 | 50 ± 20 | 18 ± 12 | 34165 ± 1888 |

added at a final concentration of IL-4 50 ng/ml, IL-10 50 ng/ml, CD40 moAb 1 μg/ml and CD27moAb 1 μg/ml.

The transfectants were present as 20% of the B-cell numbers added.

Fig. 4.

Blockage of inhibitory effect on IgE synthesis promoted by CD27 signalling. Highly purified PB B cells were cultured with IL-4 + IL-10 + CD40 moAb in the presence of CD32T, CD32–CD70T or CD32T plus CD70T with or without anti-CD70 moAb at final density of 1 × 105/well in 96-well round-bottom plates for 12–14 days. IgE levels were determined by ELISA. Results are expressed as means ± SD of ELISA triplicates.

CD27 signalling inhibited B-cell proliferation in cultures of purified B cells in the presence of a mixture of IL-4 + IL-10 + CD40 moAb (Table 2). In the presence of a mixture of IL-4 + IL-10 + CD40 moAb, plasma cell generation was also reduced by the CD32–CD70T as compared with CD32T (Fig. 3). These results suggest that CD27 signalling inhibits IgE production in the presence of IL-4, IL-10 and CD40 moAb/CD32T, by reducing B-cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells.

DISCUSSION

The present study focused on the role of IL-10 on IgE synthesis by human circulating B cells in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 signalling. IL-10 enhanced IgE production by PBMC and purified PB B cells in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 moAb/CD32T. The addition of IL-10 to B cells in the presence of the stimuli induced B-cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells, but did not affect germline ɛ transcription. In addition, CD27 signalling inhibited B-cell proliferation as well as IgE synthesis and differentiation into plasma cells in the presence of IL-10, IL-4 and CD40 moAb/CD32T.

Whether IL-10 enhances or inhibits IgE production by B cells in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 signalling has been a matter of dispute. Since IgE plays a central role in the onset of allergic disease, it is important to address the effects of IL-10, which is considered a suppressive agent in immune response, on the regulation of IgE synthesis. Several reports indicate that IL-10 inhibits IgE production by PBMC [26] or by tonsillar B cells [27] in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 moAb. Akdis et al. [17] reported that IL-10 added to purified PB B cells stimulated with IL-4 and soluble CD154 inhibited IgE production. In contrast, IL-10 has been shown to increase the IgE production by tonsillar B cells in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 moAb/CD32T [18,20]. This discrepancy is probably due to the source of B cells or a difference in B-cell stimulation, particularly CD40 signalling. To clarify the effect of IL-10 on IgE synthesis, we stimulated highly purified PB B-cells with IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T. In agreement with the findings using purified tonsillar B cells, our in vitro data demonstrated the strong enhancing effect of IL-10 on B-cell IgE synthesis.

The levels of IgE production by positive selected B cells were lower than those by PBMC. One explanation for this is that the high IgE producing cells were removed by positive selection. However, this possibility was ruled out by the fact that similar results were observed by using B cells purified by negative selection. Additional signallings from T cells and/or monocytes may induce IgE synthesis.

To produce IgE, B-cell activation, proliferation, germline ɛ transcription, class switching and differentiation into plasma cells are required. With regard to B-cell proliferation, IL-10 decreases the proliferation of SAC-stimulated B cells by promoting apoptosis [28]. However, B-cell proliferation is enhanced by IL-10 in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 moAb [18,27]. In addition, IL-10 enhances tonsillar B-cell proliferation in the presence of IL-4 + CD40 moAb/CD32T [29], similar to our findings using circulating B cells.

An early step in IgE class switching is the transcription of immature RNA from the Cɛ region, termed germline ɛ. A relationship between transcript expression and subsequent switching to Cɛ has been reported [29]. We reported previously that adding CD40 moAb alone to IL-4 did not enhance germline ɛ transcription by B cells [22]. However, after cross-linking CD40 moAb with CD32T, IL-4 and CD40 signalling enhanced germline ɛ expression compared with IL-4 alone (Fig. 2). Punnonen et al. [26] reported that IL-10 inhibits IL-4-induced germline ɛ expression in cultures of PBMC and that IL-10 has no direct effect on IL-4-induced germline ɛ transcripts in purified B cells. Since IL-10 did not enhance germline ɛ transcription by PB B cells using IL-4 and CD40 moAb/CD32T, IL-10 may not be involved in the transcription of germline ɛ.

Morphological analyses have demonstrated that IL-10 causes the terminal differentiation of tonsillar B cells into plasma cells in B-cell activation systems involving CD40 moAb/CD32T without IL-4 [20]. However, how IL-10 exerts effects on B-cell differentiation into plasma cells in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 signalling remains unclear. We demonstrated here that IL-10 promotes the differentiation of PB B cells to plasma cells in the presence of IL-4 and CD40 signalling, based on phenotypic evidence provided by flow cytometry with anti-CD38 moAb.

CD27 is well known as another molecule inducing B-cell differentiation into plasma cells [30,31]. We have previously reported that CD27 signalling promotes IL-4-induced IgE synthesis with CD40 moAb alone without cross-linking by enhancing B-cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells [22]. In this study, we examined the effect of CD27 signalling on IgE production in the presence of IL-10, IL-4 and CD40 moAb cross-linked by CD32T. Surprisingly, CD27 signalling reduced IgE production by B-cells activated with IL-10, IL-4 and CD40 moAb/CD32T. We speculated that discrepancies in the effects of CD27/CD70 interactions on IgE production were attributable to differences in stimulation. Here, the stimuli with CD40 moAb/CD32T and IL-10 in the presence of IL-4 strongly promoted IgE synthesis, compared to the system utilized in our previous study. Upon these strong stimuli, the CD27/CD70 interaction inhibited IgE synthesis. The present study found that CD27 signalling reduced IgE synthesis by purified PB B cells through inhibiting B-cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells. However, CD27 signalling did not influence the germline ɛ transcripts (data not shown). Further investigations will be needed to clarify the mechanisms of the suppressive effects on IgE synthesis of signalling via CD27.

In this study, we used the samples obtained from donors, having no allergic symptoms. In the study using allergic patient's PBMC, it was reported that IL-10 enhanced IgE synthesis in the presence of IL-4 and CD 40 moAb [15]. In contrast, IL-10 has been shown to decrease IgE production of purified PB B cells in the presence of IL-4 and soluble CD154 [17]. Further studies are necessary in order to elucidate whether IL-10 enhances or reduces IgE production of purified B cells from allergic patients.

In summary, IL-10 significantly augments IgE production by highly purified PB B cells cultured with cross-linked CD40 moAb and IL-4 by enhancing B-cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells. This is achieved without increasing the expression of germline ɛ transcripts. In contrast, CD27 signalling reduces IgE production in the presence of IL-10, IL-4 and CD40 moAb/CD32T. These findings will provide an aid to therapeutic studies of allergic diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Atsushi Komiyama for his kind guidance and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pene J, Rousset F, Briere F, et al. Interleukin 5 enhances interleukin 4-induced IgE production by normal human B cells. The role of soluble CD23 antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:929–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maggi EPG, Parronchi P, et al. Role for T cells, IL-2 and IL-6 in the IL-4-dependent in vitro human IgE synthesis. Immunology. 1989;68:300–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jabara HH, Fu SM, Geha RS, et al. CD40 and IgE. synergism between anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody and interleukin 4 in the induction of IgE synthesis by highly purified human B cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1861–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banchereau J, de Paoli P, Valle A, et al. Long-term human B cell lines dependent on interleukin-4 and antibody to CD40. Science. 1991;251:70–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1702555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebman DA, Coffman RL. Interleukin 4 causes isotype switching to IgE in T cell-stimulated clonal B cell cultures. J Exp Med. 1988;168:853–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauchat JF, Lebman DA, Coffman RL, et al. Structure and expression of germline epsilon transcripts in human B cells induced by interleukin 4 to switch to IgE production. J Exp Med. 1990;172:463–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Punnonen J, Aversa G, Cocks BG, et al. Interleukin 13 induces interleukin 4-independent IgG4 and IgE synthesis and CD23 expression by human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3730–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapira SK, Vercelli D, Jabara HH, et al. Molecular analysis of the induction of immunoglobulin E synthesis in human B cells by interleukin 4 and engagement of CD40 antigen. J Exp Med. 1992;175:289–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, et al. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gascan H, Gauchat JF, Aversa G, et al. Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies or CD4+ T cell clones and IL-4 induce IgG4 and IgE switching in purified human B cells via different signaling pathways. J Immunol. 1991;147:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, et al. The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice. impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1994;1:167–78. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muraguchi A, Hirano T, Tang B, et al. The essential role of B cell stimulatory factor 2 (BSF-2/IL-6) for the terminal differentiation of B cells. J Exp Med. 1988;167:332–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimata H. Selective enhancement of production of IgE, IgG4, and Th2-cell cytokine during the rebound phenomenon in atopic dermatitis and prevention by suplatast tosilate. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82:293–5. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimata H, Yoshida A, Ishioka C, et al. RANTES and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha selectively enhance immunoglobulin (IgE) and IgG4 production by human B cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2397–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeannin P, Delneste Y, Lecoanet HS, et al. CD86 (B7–2) on human B cells. A functional role in proliferation and selective differentiation into IgE- and IgG4-producing cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15613–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimata H, Fujimoto M, Ishioka C, et al. Histamine selectively enhances human immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG4 production induced by anti-CD58 monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1996;184:357–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akdis CA, Blesken T, Akdis M, et al. Role of interleukin 10 in specific immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:98–106. doi: 10.1172/JCI2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rousset F, Garcia E, Defrance T, et al. Interleukin 10 is a potent growth and differentiation factor for activated human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1890–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armitage RJ, Macduff BM, Spriggs MK, et al. Human B cell proliferation and Ig secretion induced by recombinant CD40 ligand are modulated by soluble cytokines. J Immunol. 1993;150:3671–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rousset F, Peyrol S, Garcia E, et al. Long-term cultured CD40-activated B lymphocytes differentiate into plasma cells in response to IL-10 but not IL-4. Int Immunol. 1995;7:1243–53. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.8.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morimoto C, Letvin NL, Distaso JA, et al. The isolation of characterization of the human suppressor inducer T cell subset. J Immunol. 1985;134:1508–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagumo H, Agematsu K, Shinozaki K, et al. CD27/CD70 interaction augments IgE secretion by promoting the differentiation of memory B cells into plasma cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6496–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karasuyama H, Kudo A, Melchers F. The proteins encoded by the VpreB and lambda 5 pre-B cell-specific genes can associate with each other and with mu heavy chain. J Exp Med. 1990;172:969–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streuli M, Morimoto C, Schrieber M, et al. Characterization of CD45 and CD45R monoclonal antibodies using transfected mouse cell lines that express individual human leukocyte common antigens. J Immunol. 1988;141:3910–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Punnonen J, de Waal Malefyt R, van Vlasselaer P, et al. IL-10 and viral IL-10 prevent IL-4-induced IgE synthesis by inhibiting the accessory cell function of monocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:1280–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uejima Y, Takahashi K, Komoriya K, et al. Effect of interleukin-10 on anti-CD40- and interleukin-4-induced immunoglobulin E production by human lymphocytes. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996;110:225–32. doi: 10.1159/000237291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itoh K, Hirohata S. The role of IL-10 in human B cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation. J Immunol. 1995;154:4341–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeannin P, Lecoanet S, Delneste Y, et al. IgE versus IgG4 production can be differentially regulated by IL-10. J Immunol. 1998;160:3555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacquot S, Kobata T, Iwata S, et al. CD154/CD40 and CD70/CD27 interactions have different and sequential functions in T cell-dependent B cell responses: enhancement of plasma cell differentiation by CD27 signaling. J Immunol. 1997;159:2652–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagumo H, Agematsu K, Shinozaki K, et al. Synergistic response of IL-10 and CD27/CD70 interaction in B cell immunoglobulin synthesis. Immunology. 1998;94:388–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]