Abstract

Epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) play a pivotal role in the initiation of cutaneous immune responses. The maturation of LCs and their migration from the skin to the T cell areas of draining lymph nodes are essential for the delivery and presentation of antigen to naïve T cells. CD40, which acts as a costimulatory molecule, is present on LCs and the basal layer of keratinocytes in the skin. We show here that systemic treatment of mice with anti-CD40 antibody stimulates the migration of LCs out of the epidermis with a 70% reduction in LC numbers after 7 days, although changes in LC morphology are detectable as early as day 3. LC numbers in the epidermis returned to 90% of normal by day 21. As well as morphological changes, LC showed up-regulated levels of Class II and ICAM-1, with only minimal changes in CD86 expression 3 days following anti-CD40 treatment. Despite increased levels of Class II and ICAM-1, epidermal LC isolated from anti-CD40 treated mice were poor stimulators of a unidirectional allogeneic mixed leucocyte reaction (MLR), as were epidermal LC isolated from control mice. These results indicate that CD40 stimulation is an effective signal for LC migration, distinct from maturation of immunostimulatory function in the epidermis, which is not altered. These observations may have important implications for the mechanism of action of agonistic anti-CD40 antibodies, which have been used as an adjuvant in models of infection and experimental tumours and the primary immunodeficiency Hyper IgM syndrome caused by deficiency of CD40 ligand.

Keywords: Langerhans cell, migration, CD40

INTRODUCTION

Epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) are the best studied example of immature dendritic cells (DCs) and play a pivotal role in the induction of cutaneous immune responses. The main functions of LCs are the recognition, internalization, processing, transport and, eventually, presentation of antigen that is encountered in the skin. Following the application of a chemical allergen LCs are induced to migrate from the skin to the draining lymph nodes, where they interact with naïve T cells migrating in from the blood [1]. During this migration the functional maturation from an antigen-uptake and processing phenotype, typical of immature DCs in nonlymphoid tissues, to an antigen-presenting phenotype, typical of DCs in lymphoid tissues, takes place [2].

Migration and maturation are central events in the initiation of cutaneous immune responses. During migration, LCs dissociate from neighbouring keratinocytes, cross the basement membrane (BM) into the dermis, enter the afferent lymphatics and subcapsular sinus leading into the draining lymph node, and relocate in the paracortical or T cell area. Epidermal cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β are known to promote LC migration from the epidermis [1]. CD40 is a cell surface receptor belonging to the TNF receptor family. It is found on B cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, haemopoietic precursors, endothelial cells and keratinocytes [3]. CD40 ligand (CD154) is found on activated T cells, activated platelets, basophils, mast cells [3] and NK cells [4]. CD40 is an important costimulatory molecule in the development of cytotoxic T cell memory, T-dependent antibody responses and B cell class switching [5]. It is also a potent survival signal for DCs [6,7] and has been shown to induce the expression of matrix metalloproteinases in human monocytes [8]. CD40 has been shown to play a role in LC migration as migration is impaired in CD40 ligand knockout mice [9]. We hypothesized that CD40 ligation may be involved in both the migration and maturation of LC’s. In this study we investigated the effects of several agonistic anti-CD40 antibodies in vivo on LC numbers in the epidermis and DC numbers in lymph nodes of mice. LC maturity was assessed by expression of CD86, ICAM-1 and MHC Class II and the immunostimulatory function of LCs determined in a unidirectional allogeneic mixed leucocyte reaction (MLR) [10].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female, six to eight week old BALB/c, CBA × C57BL/10 F1, 129Sv and CD40 knockout mice (Dr D. Gray, University of Edinburgh), bred in the Specific Pathogen Free Unit, National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), Mill Hill, London, UK, were used for these studies.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for these studies: M5/114 [11] (anti I-Ad and anti I-Ed, rat IgG2b); isotype matched control MAC193 (anti-ovine placental lactogen, rat IgG2a) obtained from Dr G. Butcher (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK), 3/23 (anti-murine CD40, rat IgG2a), 1C-10 (anti-murine CD40, rat IgG2a) and 24G2 (anti-murine CD32, rat IgG) obtained from Dr G. Klaus, NIMR, London, NLDC-145 (anti-interdigitating cell, rat IgG2a [12] obtained from Dr B. Stockinger, NIMR, London. These antibodies were purified from hybridoma tissue culture supernatants by affinity chromatography using a protein G HiTrap column (Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Fifty mg of FITC (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) per mg of antibody (M5/114) was used for conjugation. R-PE conjugated hamster anti-mouse CD86 (B7-2) and ICAM-1 (3E2) were obtained from Pharmingen, Becton Dickinson, UK Ltd.

Preparation and analysis of epidermal sheets

Epidermal sheets were prepared from mouse ears, or from skin explants, as previously described by Cumberbatch et al.[13]. Briefly, dorsal ear halves from naïve mice, or following culture, were incubated in 0·02m ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma Chemical Co.) in PBS, for 1–1·5h. The epidermal sheet was separated using forceps. Epidermal sheets were fixed in acetone for 20 min at −20°C, washed three times with PBS and then incubated for a minimum of 30min at room temperature with anti-MHC class II – FITC (M5/114 – FITC; 25μg/ml), diluted in PBS containing 0·2% BSA. Sheets were then mounted onto glass microscope slides in Citifluor (Citifluor Ltd, London, UK) for fluorescence analysis.

LC were enumerated by counting MHC class II positive cells in epidermal sheets. For each sheet, five areas were chosen at random, photographed at ×440 magnification using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70 inverted microscope, Japan). Digital images were acquired using a Photometrics CH350L liquid cooled CCD camera and Deltavision Deconvolution software. Image analysis was performed using Scionimage shareware and the number of MHC class II positive cells counted per image, which corresponded to an area of 0·12mm2. Cell frequency was converted to LC/mm2 and results expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of a minimum of 10 images. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's T-test.

Skin explant assay

Naïve mice were killed by CO2 inhalation and the ears cut at the base with scissors. The ears were washed twice with PBS and then with 70% ethanol to sterilize. Under sterile conditions the ears were allowed to dry and split into dorsal and ventral halves with forceps. The dorsal halves were floated individually on 1–2ml of RPMI-FCS (RPMI-1640 medium, Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd, Irvine, UK) in 16mm diameter wells of 24 well cluster trays (Costar Corp., Cambridge, MA). The explants were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. At 48 h, epidermal sheets were removed and epidermal cell suspensions made as described below.

Preparation of epidermal cell and lymph node suspensions

Ears from naïve and anti-CD40 moAb (3/23) treated mice, or skin explants were separated into dorsal and ventral halves with forceps. Dorsal halves were incubated in 0·6% trypsin (Gibco BRL) in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco BRL) and ventral halves in 1% trypsin for 60 min at 37°C. Epidermal sheets were removed with forceps and agitated in RPMI-1640 containing supplements (see above) and 10% (v/v) FCS. Single cell suspensions of epidermal cells were prepared by filtration to remove the epidermal sheet remnants. The cells were washed twice in RPMI containing 10% FCS and then resuspended in RPMI-FCS. The cells were analysed by flow cytometry (FACS Vantage, San Jose, CA) using Win MDI 2·8 shareware for CD86, ICAM-1 and MHC Class II expression (the epitope seen by anti-CD80 moAb 16–10A1 (Becton Dickinson) is trypsin sensitive). Each analysis used at least 50000 events of which 2–4% were LC.

Auricular lymph nodes were removed and cell suspensions made by disruption through 70 μm cell strainers (Becton Dickinson). The cells were washed twice in RPMI containing 10% FCS and then resuspended in RPMI-FCS. DCs were enriched for by density gradient centrifugation, 2 ml of metrizamide (Nycomed; 14·5% in RPMI-FCS) were layered under 8 ml of Lymph node cells and centrifuged (600 g) for 15 min at room temperature. Interface cells (the low buoyant density fraction) were collected, washed once and resuspended in RPMI-FCS. The cells were stained and analysed by flow cytometry for MHC Class II and NLDC-145 expression.

Antibody treatment

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 250 μg of anti-CD40 antibody or an isotype matched control antibody (MAC-193) diluted in sterile PBS. This dose of antibody was chosen as it had been previously optimized in mice to produce splenomegaly (data not shown) and corresponded with other studies using similar amounts (200 μg) [9]. Ears were taken and Langerhans cells enumerated on days 3, 4 and 7 or as otherwise stated.

Flow cytometric sorting of Langerhans cells

Epidermal cell suspensions were made as described and the resulting cells resuspended in 1ml of RPMI-1640 containing supplements (see above) and 10% (v/v) FCS. The Langerhans cells were stained with FITC conjugated anti-CD32 antibody (24G2 rat anti-murine CD32, IgG) for 30min at 4°C, washed twice in RPMI-1640 containing supplements and 10% (v/v) FCS and 1 × 105 CD32 positive cells sorted using the MoFlo sorter (Cytomation, Colorado, USA) to a purity of greater than 90%.

Mixed leucocyte reaction

Female BALB/c mice were injected ip with either 250 μg MAC193 or 3/23. Ears and lymph nodes were removed and cell suspensions prepared. Epidermal cells suspensions were made as previously described. Lymph node cell suspensions from CBA × C57BL/10 F1 mice were generated by mechanical disaggregation through a mesh, and fragments were removed by filtration. These responder cells were used at a concentration of 2 × 105 per well. Langerhans cells were stained with anti-CD32 FITC and 1 × 105 sorted to greater than 90% purity by flow cytometry. Cells were plated in 96 well round -bottomed plates (Nunclon), in IMDM plus 10% FCS and incubated for a total of four days at 37°C. 3H thymidine (0·5 μCi/well) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) was added for 16h incubation, the cells harvested using an automated cell harvester and counted for thymidine incorporation (Wallac 1205 Betaplate counter). The proliferation index was calculated by dividing the incorporated counts by the background counts (lymph node responder cells alone) and results are mean ± SEM of three replicates. The software package used was GraphPad Prism 2·00.

RESULTS

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on epidermal Langerhans cell numbers and morphology

We first analysed the effect of anti-CD40 antibody (clone 3/23) on the numbers of epidermal LC on days 3, 4 and 7 following a single intraperitoneal injection of 250μg antibody in BALB/c mice, Fig. 1a. The numbers of LC started to decline by day 4 and were reduced to 30% of control value by day 7. LC numbers returned to 90% of normal by day 21 (data not shown), by which time the antibody would have been cleared. Isotype matched control antibody MAC 193 had no effect on LC numbers at any time point studied. To determine whether these findings were related to the use of clone 3/23, we performed similar studies using another anti-CD40 antibody, clone 1C10 [14]. The data for 1C10 are shown in Fig. 1b and the kinetics of LC decline are similar to those for 3/23 in that a reduction in LC numbers is seen after 3 days and by day 7 LC numbers are reduced to 20% of control.

Fig. 1.

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on epidermal Langerhans cell numbers and morphology in the ear skin of mice. (a) The numbers of LC in the epidermis at days 3, 4 and 7 days following a single i.p. injection of 250μg anti-CD40 antibody (clone 3/23) or isotype-matched control antibody (MAC193) are shown. Results are average numbers of LC ± SEM per mm2 measured in 10 digital images taken at random from 2 ears per group and are from one representative experiment of at least three performed. □ MAC 193;  ; anti-CD40. P-values are: *P = 1·6 × 10−11, **P = 2·3 × 10−15. (b) The numbers of LC in the epidermis at days 1, 3, and 7 following a single i.p. injection of 250 μg moAb 1C10 (anti-CD40) are shown. The control moAb, MAC 193, had no effect on LC numbers and the data on days 1, 3 and 7 have been pooled. P-values are: *P = 4 × 10−8, **P = 1·1 × 10−25. Results are as described in legend to Fig. 1a. (c) Langerhans cells stained with MHC Class II FITC in epidermal sheets of anti-CD40 (3/23) and control moAb (MAC193)-treated mice at days 3, 4 and 7 after a single i.p. injection of 250 μg antibody (original magnification × 200). Increases in the size of LC and MHC Class II expression are seen on days 3 and 4 before effects on LC numbers, which are most marked by day 7. (d) CD40 knockout and 129/Sv wildtype mice were given a single i.p. injection of anti-CD40 antibody (3/23) or control moAb (MAC193) and the numbers of LC counted on day 7. The statistical difference in the LC numbers between the anti-CD40 treated control and CD40 knockout mice is *P = 3·1 × 10−5. Results are as described in legend to Fig. 1a.

; anti-CD40. P-values are: *P = 1·6 × 10−11, **P = 2·3 × 10−15. (b) The numbers of LC in the epidermis at days 1, 3, and 7 following a single i.p. injection of 250 μg moAb 1C10 (anti-CD40) are shown. The control moAb, MAC 193, had no effect on LC numbers and the data on days 1, 3 and 7 have been pooled. P-values are: *P = 4 × 10−8, **P = 1·1 × 10−25. Results are as described in legend to Fig. 1a. (c) Langerhans cells stained with MHC Class II FITC in epidermal sheets of anti-CD40 (3/23) and control moAb (MAC193)-treated mice at days 3, 4 and 7 after a single i.p. injection of 250 μg antibody (original magnification × 200). Increases in the size of LC and MHC Class II expression are seen on days 3 and 4 before effects on LC numbers, which are most marked by day 7. (d) CD40 knockout and 129/Sv wildtype mice were given a single i.p. injection of anti-CD40 antibody (3/23) or control moAb (MAC193) and the numbers of LC counted on day 7. The statistical difference in the LC numbers between the anti-CD40 treated control and CD40 knockout mice is *P = 3·1 × 10−5. Results are as described in legend to Fig. 1a.

Changes in the morphology of LC preceded their rapid egress from the epidermis and can be observed by day 3 following anti-CD40 treatment (3/23), Fig. 1c (original magnification ×200 for all images). LC increased in size, the number and length of dendrites appeared to increase and the intensity of MHC Class II staining was up-regulated. These observations suggested that LC maturation may be occurring while the cells were still in the epidermis.

To eliminate the possibility that the effects on LC numbers and maturation were due to a contaminant in the anti-CD40 antibody preparations, the effect of anti-CD40 moAb was studied in the CD40−/− mouse, Fig. 1d. LC numbers declined normally in response to anti-CD40 in the matched wildtype 129/Sv mouse and were reduced to 37% of control. In contrast, the numbers of epidermal LC were not affected at 7 days following administration of 3/23 to CD40−/− mice. The results suggest that antibody binding to CD40 is required to stimulate LC migration and that non specific factors are not playing a major role in this system.

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on the phenotype of epidermal Langerhans cells

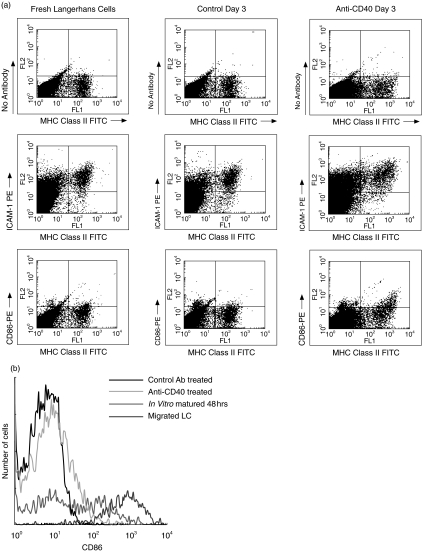

Following the observation that MHC Class II staining was increased, Fig. 1c, the expression of MHC Class II and other markers of dendritic cell maturation (CD86 and ICAM-1) were analysed by flow cytometry of epidermal cell suspensions, Fig. 2a. LC were isolated from ear skin of mice 3 days following treatment with anti-CD40 or control moAb and compared with LC isolated from fresh skin, LC isolated from skin explants following 48h culture and LC which had migrated out of explants. MHC Class II positive LC isolated from fresh skin did not express CD86 but did express ICAM-1, as described previously [13,15,16]. LC isolated from ear skin of control moAb treated mice were indistinguishable from fresh LC. However, anti-CD40 treatment up-regulated MHC Class II, ICAM-1 and CD86 expression on LC after 3 days. The extent of CD86 up-regulation was not as great as on LC which had matured in skin explants and been isolated following 48h of culture, or on LC which had migrated out of explants by 48h, Fig. 2b, and was confined to LC expressing highest levels of MHC Class II. Together, these results suggest that while anti-CD40 driven maturation occurs, it is incomplete for LC in the epidermis. In keratinocytes (upper and lower left quadrants of plots in Fig. 2a) ICAM-1 and, to a lesser extent, MHC Class II expression were also up-regulated in a proportion of cells in the anti-CD40 antibody treated group, however, a clear distinction remained between KC and LC (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on the phenotype of epidermal Langerhans cells. (a) BALB/c mice injected with either anti CD40 antibody (3/23) or control antibody (MAC 193) were killed after 3 days. Epidermal cell suspensions were made, the cells stained for MHC Class II, CD86 and ICAM-1 and analysed by flow cytometry. The expression of MHC Class II, CD86 and ICAM-1 on fresh Langerhans cells isolated from ear skin of normal mice were compared. The level of expression of these markers of maturity is increased in the CD40 treated LC. (b) In vitro matured epidermal Langerhans cells isolated from 48h skin explant organ cultures and migrated LC were used to compare the expression of CD86. The expression of CD86 is increased in the CD40 treated LC but not to the extent of the epidermal LC which have a bimodal expression of CD86 or the migrated LC derived from explants.

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on lymph node dendritic cell numbers

To determine whether the decline in epidermal LC numbers was due to migration out of the epidermis rather than due to apoptosis, the numbers of dendritic cells in the auricular and trochlear lymph nodes were measured 7 days following treatment of mice with anti-CD40 or control moAb. Lymph node cell suspensions were made and dendritic cells enriched by gradient centrifugation. Dendritic cells were identified by dual staining for MHC Class II and NLDC 145 (DEC-205), Fig. 3. The results show a clear increase in the number of dendritic cells in LN of anti-CD40 treated mice from 7 to 22%. This is likely to represent an underestimate of the true increase as the percentage does not take into account the two to three fold increase in the size of the lymph nodes in anti-CD40 treated mice (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on lymph node dendritic cell numbers. BALB/c mice injected with either (a) anti-CD40 antibody (3/23) or (b) control antibody (MAC 193) were killed on day 7. Lymph nodes were removed and cell suspensions were enriched for dendritic cells by metrizamide gradient centrifugation. Dendritic cells were identified by coexpression of MHC Class II and NLDC-145. The double positive cells in the control antibody treated group is 7% compared with 22% in the CD40 treated mice.

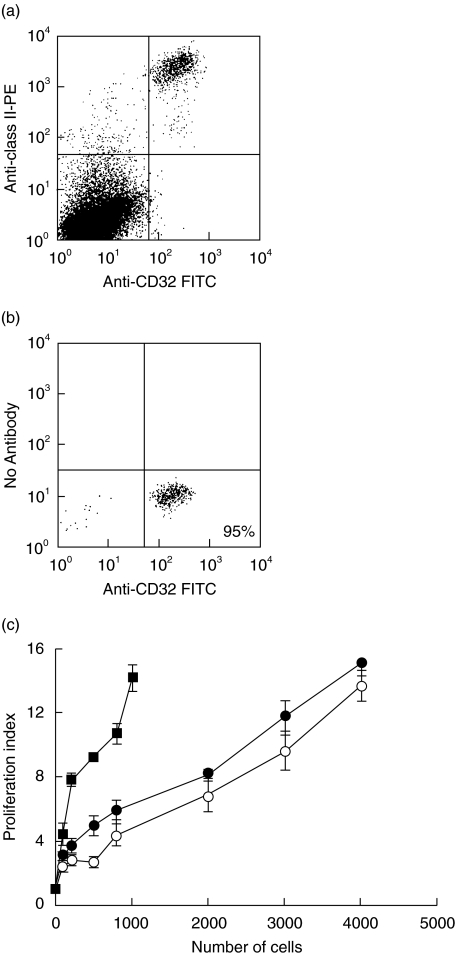

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on antigen presenting cell function of purified epidermal Langerhans cells

Following the observation that anti-CD40 treatment generated LC with a more mature phenotype, the effect on antigen presenting cell function of LC was determined in a unidirectional mixed leucocyte reaction (MLR). In epidermal cell suspensions LC express CD32 (FcγRII), Fig. 4a; this marker was therefore used to sort LC from other epidermal cells such as keratinocytes and dendritic epidermal T cells, which could affect the MLR. This approach also allowed the number of LC added to each well in the MLR to be more accurately determined than using unsorted epidermal cell suspensions in which the percentage of LC may differ between treatment and control groups. Another dendritic cell marker, NLDC 145 (DEC 205) was found to be trypsin sensitive and anti-MHC Class II moAb inhibited the MLR (data not shown); these antibodies could therefore not be used for sorting and/or analysis of LC in the MLR. Dendritic cells also express CD32 and inclusion of anti-CD32 antibody in an MLR in which lymph node dendritic cells were used as stimulator cells had minimal effect on proliferation by responder cells (data not shown). LC were purified from epidermal cell suspensions of anti-CD40 and control moAb-treated BALB/c mice 3 days following injection of antibody by gating on CD32 positive cells and sorting using the flow cytometer. Populations of LC enriched to >90% purity were routinely isolated using this method (Fig. 4b). Increasing numbers of sorted LC were incubated with a fixed number of responder cells isolated from lymph nodes of CBA × C57BL/10 F1 mice and incubated for 4 days. The proliferation of responder cells was compared to that stimulated by LC which had been matured in vitro for 48 h in skin explant organ culture and subjected to the same isolation and sorting procedures. As shown in Fig. 4c, LC isolated from the epidermis of anti-CD40 treated mice stimulated proliferation of responder cells but the responses were similar to those elicited by LC from control moAb-treated mice. However, in vitro matured LC which had migrated out of the epidermis were at least 4-fold more potent when compared on a cell dose basis. In order to ensure that the anti-CD40 moAbs did not block CD40 costimulation in an MLR, they were incubated with migrated LC (from explants after 48 h of culture) for 30 min The LC were then washed and these cells then used as stimulators. There was no inhibition of the MLR compared with controls (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

The effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on antigen presenting cell function of purified epidermal Langerhans cells. (a) BALB/c mice injected with either anti CD40 antibody (3/23) or control antibody (MAC 193), were killed on day 3. Epidermal cell suspensions were stained with anti-CD32 FITC and anti-MHC Class II PE to verify the anti-CD32 staining of LC. (b) Epidermal cell suspensions were made and the cells stained with CD32 FITC and sorted to >90% purity by flow cytometry. (c) Sorted LC were used as stimulators in a unidirectional MLR. In vitro matured and sorted LC which had migrated from 48 h skin explant organ cultures were used as a positive control (these had also been subjected to trypsin). ○ Control Ab; • Anti-CD40; ▪ Migrated cells Results are mean proliferation index of each triplicate ± SEM from a representative experiment which has been repeated 3 times with similar results.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that systemic treatment of mice with anti-CD40 antibody stimulates the migration of epidermal LC over a period of 7 days resulting in a 70% reduction of cell numbers in the skin. This was associated with an increase in MHC Class II+, NLDC145+ DC in the draining lymph nodes. This subset may include DC other than LC and it will be of interest to stain these DC with the new LC specific marker Langerin. The epidermal LC phenotype in anti-CD40 treated mice was found to be more mature in terms of MHC Class II and ICAM-1 expression. However, CD86 up-regulation was incomplete when compared with LC isolated from skin explants cultured for 48h, or with LC, which migrated out of skin explants over this time period.

In a recent paper Moodycliffe et al.[9] demonstrated a role for CD40/CD40L interactions in LC migration using the CD40L knockout mouse. Langerhans cells in CD40L knockout mice were shown to have impaired migration from the epidermis following contact sensitization. Systemic treatment with the anti-CD40 antibody (1C10), or local administration of TNF-α, were shown to restore LC migration in these mice with almost an 80% reduction in LC by 18h. Our data clearly support a role for CD40 ligation in LC migration, although we find virtually no change in LC numbers by 24h following systemic treatment with moAb 1C10.

This discrepancy may be explained by differences in experimental technique, as Moodycliffe et al.[9] studied shaved abdominal skin whereas we used unshaved ear skin. In addition, Moodycliffe et al. studied C57BL/6 mice following injection of 200μg of anti-CD40 (1C10) and we have analysed BALB/c mice following 250μg of 3/23 or 1C10. LC enumeration was also different in that Moodycliffe et al. identified LC in skin using the moAb DEC205 and we have used an anti-MHC Class II moAb (M5/114).

The migration kinetics of LC following anti-CD40 treatment in our study are clearly very different in comparison with the reduction in LC numbers of ~80% following the intradermal injection of TNF-α or systemic treatment with anti-CD40 reported by Moodycliffe et al.[9]. It has been shown that CD40 ligation induced secretion of TNF-α by CD40 positive basal keratinocytes [17], which is a migration stimulus for LC [18]. The effects of TNF-α have been reported to be very rapid as changes in LC density were observed at 30 min [19] following intradermal TNF-α injection. The percentage of LC which migrated out of the epidermis following intradermal TNF-α in BALB/c mice was between 15% and 27% at 30min with no further increase in migration at 2h [19].

Our results demonstrate a gradual migration of LC from the epidermis following anti-CD40 moAb, suggesting either a gradual build up of a second messenger like TNF-α, or that TNF-α is not the effector, because of its expected rapid effects [19] on LC expressing the TNFR2 [20]. The study using the CD40 knockout mice suggests that factors such as LPS are unlikely to play a major role as migration of LC would be expected in the absence of CD40 ligation. The systemic effects of anti-CD40 antibodies on cytokine and chemokine production also need to be considered. Indeed mice treated with anti-CD40 moAbs have been demonstrated to have significant splenomegaly [21].

The only CD40 expressing cells in the epidermis are basal keratinocytes and LC, however, the mechanisms of anti-CD40 moAb induced LC migration are not clear as to whether an indirect or direct stimulus is needed. The question whether LC migration is stimulated by anti-CD40 binding to LC or keratinocytes in the skin is critical. This could be addressed in further studies using bone marrow chimeras generated by irradiating normal CD40+/+ mice and reconstituting with CD40−/− bone marrow, resulting in mice with CD40 positive keratinocytes and CD40 negative LC, which would then be given anti-CD40 moAbs.

CD40 ligation has been shown to enhance immune responses in a number of tumour and infection models [22–24]. However in this study the MLR results indicate no difference between epidermal LC isolated from anti-CD40 and control moAb treated mice in their capacity to act as APC. At first these results appear to conflict, but it is clear that the overall result of CD40 ligation is likely to be immunostimulatory, however, LC taken from an epidermal location appear not to have attained full antigen presenting function. Indeed it would seem detrimental for LC to become fully mature while in the epidermis as they would be unable to prime T cells in this location and may induce immunopathology.

The increase in CD86 expression in the anti-CD40 treated epidermal LC is only partial and it is not clear whether other factors, such as cytokine secretion, in addition to up-regulated CD86 expression, determine the full functional maturity of LC. The anti-CD40 moAb 3/23 did not inhibit an MLR when added to LC which had migrated out of skin explants after 48h (data not shown), suggesting it did not block costimulation or induce apoptosis.

It would be of interest to determine whether the effects of anti-CD40 on LC migration are mediated by up-regulation of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Expression of CCR7 is up-regulated upon maturation of dendritic cells cultured from human monocytes and CD1a positive DC's [25] and the migration of LC from the epidermis to the draining lymph node is impaired in CCR7 deficient mice [26]. However, antibodies to mouse CCR7 are not yet available and antibodies to human CCR7 do not cross-react with murine CCR7.

The reproducible kinetics of LC migration in this model suggest that the effects of anti-CD40 antibody may also be used as an in vivo system to study the effects of other interventions which may interfere with LC mobilization and maturation. Anti-CD40 therapy has also been proposed as a potential vaccine adjuvant [27] and has been demonstrated to bypass T cell help in murine models [23, 28–30]. The finding that anti-CD40 antibody causes the in vivo mobilization of a substantial antigen presenting cell population from the skin (the largest organ in the body), is of importance for vaccine design and may explain some of these reported findings.

Finally there may be implications for patients with the human primary immunodeficiencies (PID) such as Hyper IgM Syndrome in whom there is a deficiency of CD40 ligand [31] resulting in a combined immunodeficiency affecting both humoral and cellular arms of the immune system. CD40/CD40 Ligand effects on the migration of LC and potentially other DC subsets may underlie some of the observed immunological impairment. Another PID is idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia, which is associated with very severe warts. Induction of the migration and maturation of LC by CD40 ligation and the simultaneous ability to bypass the requirement for CD4 T cell help [23] potentially inducing human papilloma virus specific cytotoxic effector cells, is theoretically attractive especially as treatment could be delivered locally.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Jenny Hughes for careful reading of the manuscript, Chris Atkins for assistance with flow cytometry, Dr Stamatis Pagakis for assistance with immunofluorescence and digital images, and Frank Johnson, Lesley Millar and Joe Brock for the figures. Stephen Jolles is currently a Leukaemia Research Foundation Fellow and was supported by an MRC Clinical Training Fellowship and Peel Medical Research Trust Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kimber I, Cumberbatch M, Dearman RJ, Bhushan M, Griffiths CE. Cytokines and chemokines in the initiation and regulation of epidermal Langerhans cell mobilization. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:401–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, et al. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner JG, Rakhmilevich AL, Burdelya L, Neal Z, Imboden M, Sondel PM, Yu H. Anti-CD40 antibody induces antitumor and antimetastatic effects: the role of NK cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:89–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. Functions of CD40 on B cells, dendritic cells and other cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:330–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLellan A, Heldmann M, Terbeck G, Weih F, Linden C, Brocker EB, Leverkus M, Kampgen E. MHC class II and CD40 play opposing roles in dendritic cell survival. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2612–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2612::AID-IMMU2612>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane PJ, Brocker T. Developmental regulation of dendritic cell function. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:308–13. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik N, Greenfield BW, Wahl AF, Kiener PA. Activation of human monocytes through CD40 induces matrix metalloproteinases. J Immunol. 1996;156:3952–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moodycliffe AM, Shreedhar V, Ullrich SE, Walterscheid J, Bucana C, Kripke ML, Flores-Romo L. CD40–CD40 Ligand Interactions In Vivo Regulate Migration of Antigen-bearing Dendritic Cells from the Skin to Draining Lymph Nodes. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2011–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen CP, Steinman RM, Witmer-Pack M, Hankins DF, Morris PJ, Austyn JM. Migration and maturation of Langerhans cells in skin transplants and explants. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1483–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhattacharya A, Dorf ME, Springer TA. A shared alloantigenic determinant on Ia antigens encoded by the I-A and I-E subregions: evidence for I region gene duplication. J Immunol. 1981;127:2488–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraal G, Breel M, Janse M, Bruin G. Langerhans’ cells, veiled cells, and interdigitating cells in the mouse recognized by a monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1986;163:981–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.4.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cumberbatch M, Gould SJ, Peters SW, Kimber I. MHC class II expression by Langerhans’ cells and lymph node dendritic cells: possible evidence for maturation of Langerhans’ cells following contact sensitization. Immunology. 1991;74:414–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heath AW, Wu WW, Howard MC. Monoclonal antibodies to murine CD40 define two distinct functional epitopes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1828–34. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cumberbatch M, Kimber I. Phenotypic characteristics of antigen-bearing cells in the draining lymph nodes of contact sensitized mice. Immunology. 1990;71:404–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuler G, Steinman RM. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells mature into potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1985;161:526–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.3.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peguet-Navarro J, Dalbiez-Gauthier C, Moulon C, et al. CD40 ligation of human keratinocytes inhibits their proliferation and induces their differentiation. J Immunol. 1997;158:144–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cumberbatch M, Griffiths CE, Tucker SC, Dearman RJ, Kimber I. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha induces Langerhans cell migration in humans. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:192–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cumberbatch M, Fielding I, Kimber I. Modulation of epidermal Langerhans’ cell frequency by tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Immunology. 1994;81:395–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larregina A, Morelli A, Kolkowski E, Fainboim L. Flow cytometric analysis of cytokine receptors on human Langerhans’ cells. Changes observed after short-term culture. Immunology. 1996;87:317–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.451513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia de Vinuesa C, MacLennan IC, Holman M, Klaus GG. Anti-CD40 antibody enhances responses to polysaccharide without mimicking T cell help. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3216–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3216::AID-IMMU3216>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferlin WG, von der Weid T, Cottrez F, Ferrick DA, Coffman RL, Howard M. C., The induction of a protective response in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice with anti-CD40 moAb. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:525–31. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<525::AID-IMMU525>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.French RR, Chan HT, Tutt AL, Glennie MJ. CD40 antibody evokes a cytotoxic T-cell response that eradicates lymphoma and bypasses T-cell help. Nat Med. 1999;5:548–53. doi: 10.1038/8426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaussabel D, Jacobs F, de Jonge J, de Veerman M, Carlier Y, Thielemans K, Goldman M, Vray B. CD40 ligation prevents Trypanosoma cruzi infection through interleukin-12 upregulation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1929–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1929-1934.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caux C, Ait-Yahia S, Chemin K, et al. Dendritic cell biology and regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by chemokines. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2000;22:345–69. doi: 10.1007/s002810000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dullforce P, Sutton DC, Heath AW. Enhancement of T cell- independent immune responses in vivo by CD40 antibodies. Nat Med. 1998;4:88–91. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diehl L, den Boer AT, Schoenberger SP, van der Voort EI, Schumacher TN, Melief CJ, Offringa R, Toes RE. CD40 activation in vivo overcomes peptide-induced peripheral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte tolerance and augments anti-tumor vaccine efficacy. Nat Med. 1999;5:774–9. doi: 10.1038/10495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Tubb E, et al. Conversion of tumor-specific CD4+ T-cell tolerance to T-cell priming through in vivo ligation of CD40. Nat Med. 1999;5:780–7. doi: 10.1038/10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermans IF, Ritchie DS, Daish A, Yang J, Kehry MR, Ronchese F. Impaired ability of MHC class II-/- dendritic cells to provide tumor protection is rescued by CD40 ligation. J Immunol. 1999;163:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Union of Immunological Societies. Primary immunodeficiency diseases. Report of an IUIS Scientific Committee. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118(Suppl. 1):1–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]