Abstract

Bronchiolitis caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is a major cause of hospitalization in children under 1 years of age. The disease characteristically does not induce protective immunity. However, a mononuclear peribronchiolar and perivascular infiltrate during RSV infection is suggestive of an immune-mediated pathogenesis. Macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) play an essential role in the initiation and maintenance of immune response to pathogens. To analyse interactions of RSV and immune cells, human cord blood derived macrophages and dendritic cells were infected with RSV. Both cells were found to be infected with RSV resulting in the activation of macrophages and maturation of dendritic cells as reflected by enhanced expression of several surface antigens. In the next set of experiments, generation of mediators was compared between cells infected with RSV, parainfluenza (PIV3) and influenza virus as well as ultracentrifuged virus free supernatant. Whereas the supernatant did not induce release of mediators, all three live virus infections induced IL-6 production from macrophages and DC. Influenza virus infection induced predominantly IL-12 p75 generation in DC. In contrast, RSV induced strong IL-11 and prostaglandin E2 release from both macrophages and DCs. In addition, RSV but not influenza and parainfluenza virus induced a strong IL-10 generation particularly from macrophages. Since IL-10, IL-11 and PGE2 are known to act immunosuppressive rather than proinflammatory, these mediators might be responsible for the delayed protective RSV specific immune response.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, dendritic cells, macrophages, interleukin-10, interleukin-11, prostaglandin E2

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus affects about 90% of infants and young children by the age of 2 years. Peak rates occur in infants aged 6 weeks to 6 months [1]. Recently, a long lasting change in forced expiratory volume has been attributed to an RSV infection during infancy [2]. In addition, an increase in Th2 mediated atopy detectable up to 7 years after RSV infection was reported [3]. A mononuclear peribronchiolar and perivascular infiltrate during RSV infection is suggestive of an immune-mediated pathogenesis. However, despite the vigorous inflammatory response protection against RSV is not complete and is of short duration. Even adults with the history of natural RSV infection are shown to be susceptible to reinfection with the same strain of the virus for several times [4]. These features point to a profound immunomodulatory capacity of the RSV virus. Clinical studies suggest that monocytes may play a role in the pathophysiology involved in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis. Monocytes of children who have to be ventilated produce low levels of IL-12 during the course of acute disease [5]. On the other hand, IL-10 levels generated by peripheral monocytes during the convalescent phase, are significantly higher in patients who developed recurrent wheezing during the year after RSV bronchiolitis than in patients without recurrent episodes of wheezing [6]. However, monocytes represent a pool of circulating precursors that differentiate into macrophages, the scavengers of the immune system, or dendritic cells (DCs), that are able to present pathogen-derived peptides to naive T cells thereby initiating immune responses [7]. Furthermore, other mediators as prostaglandin E2[8] and interleukin-11 [9] are implicated in the pathophysiology of RSV associated disease.

In this study, we have investigated the interactions of RSV with human macrophages and dendritic cells derived from cord blood myeloid progenitor cells. We have examined the modulation of host cell activation markers during RSV infection and analysed the cytokine gene expression from RSV-infected cells focusing on their ability to stimulate IL-6, IL-12p75, IL-10, IL-11 and PGE2 production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of macrophages and dendritic cells from cord blood

Heparinized cord blood was obtained from newborns at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Augusta or St. Elisabeth Hospital). Parents gave informed written consent before the blood was studied. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty. Blood was drawn by puncture of the umbilical vein of the placenta after maternal blood had been wiped off. No contamination with maternal IgA was detected. The blood for further cellular analysis was placed in a 50-ml sterile Falcon tube (Falcon, Heidelberg, Germany) containing 10ml of HBSS with 100IU penicillin, 100μg/ml streptomycin, 2·5μg/ml amphotericin B and 50IU/ml of heparin (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). Only samples not older than 60min were processed. Mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll density centrifugation. Hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from mononuclear fractions through positive selection, using anti-CD34 coated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and MiniMACS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec). In all experiments, the isolated cells were 95–99% CD34 positive.

Hematopoietic progenitor cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells ml in 24 well flat bottom plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany). Culture medium consisted of endotoxin free RPMI 1640 (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) containing 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100IU penicillin, 100μg/ml streptomycin, 2mm of glutamine and 1mm of sodium pyruvate (all from Biochrom). Cultures were supplemented with rhGM-CSF (100ng/ml, Novartis, Nürnberg, Germany) rhTNF-α (2·5ng/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and rhSCF (100ng/ml; Peprotech). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere in the presence of 5% CO2 for 7 days. Thereafter, the cells were split and cultured with fresh medium with rhGM-CSF (100ng/ml), TNF-α (2·5ng/ml) and either IL-4 (50U/ml, Peprotech) to culture DCs or M-CSF (25U/ml, Peprotech) to generate macrophages. Macrophages were purified by positive sorting using anti-CD14-conjugated magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Dendritic cells were purified by using CD1a microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).

Preparation of viruses and infection with viruses

The viruses that were employed included: RSV Long strain, Parainfluenza type 3 (PIV3) C 243 strain, Influenza PR8 strain. Viral stocks were prepared by infection of sensitive cell systems with a low input multiplicity of infection (MOI). Hep-2 cells were used for RSV as described before [10], dog kidney epithelial cells (MDCK) were used for PIV3 and influenza. When infection was advanced, cell supernatants were harvested, cells disrupted by ultrasonication and debris pelleted by low speed centrifugation. Supernatants containing viruses were frozen at −80°C. Infectivity titres of stock viruses were determined by inoculation of serial dilutions into sensitive cell systems as indicated above. Virus growth was detected by observation of typical cytopathic effects followed by immuno-cytochemical staining of infected cell monolayers. Virus free supernatants were obtained after stock virus ultra centrifugation (130000 g). Cell lines and virus preparations were tested for mycoplasma by PCR with a mycoplasma detection kit as described in the manufacturer's manual (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA).

Fluorescence staining

Cultured cells were washed twice, the concentration adjusted to 2 × 105 cells in HBSS and incubated with the appropriately diluted antibodies against surface proteins for 20min at 4°C. Expression of costimulatory molecules was detected by appropriate FITC labelled antibodies specific for MHC class I, MHC class II, CD80, CD83, CD86, CD40, CD54 or CD18, respectively (all from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

To determine the rate of RSV infection permeabilization of the cell membrane was achieved by resuspension in 100μl HBSS containing 0·1% saponin and 0·01m Hepes buffer (saponin buffer). The permeabilized cells were incubated with biotinylated goat-anti-RSV (Biodesign, Saco, ME, USA) for 20min at 4°C, washed with saponin buffer and subsequently incubated with FITC-labelled streptavidin for 20min at 4°C in the dark. After washing with saponin buffer the cells were resuspended in 200μl HBSS for flow cytometric analysis.

Data acquisition and analysis

A FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, USA) equipped with filter settings for FITC (530nm) (FL-1), for PE (585nm) (FL-2) was used. Ten thousand events were acquired in list mode and analysed using LYSIS II software.

ELISA

Cytokines were measured with ELISA kits (R & D, Wiesbaden, Germany) on cell-free supernatants. Data are expressed as picograms per ml ± SD of triplicate cultures. The IL-12 ELISA detects the bioactive IL-12p75 heterodimer only.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

Samples for the determination of PGE2 were prepared as described before [11]. Measurements were performed on a Finnigan MAT TSQ700 GC/MS/MS system equipped with a Varian Model 3400 gas chromatograph and a CTC A200S autosampler.

RESULTS

Infection of human macrophages and DCs with RSV

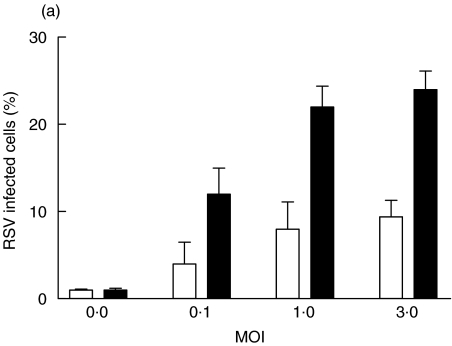

Initial studies were designed to determine the infectivity of RSV in macrophages and DCs. Macrophages and immature DCs were generated from the same blood donors and were allowed to differentiate in culture for 14 days. Once their differentiated phenotypes were acquired, the cells were infected with increasing MOI (Fig. 1). The percentages of infected cells were measured 24h after infection by staining with a RSV specific polyclonal antiserum. A clear difference was observed in the percentage of infected cells, which was 2-fold higher in macrophages compared with DCs.

Fig. 1.

Infection of DCs and macrophages with RSV. Human cord blood derived DCs and macrophages were infected with increasing MOI. After 24 h of infection at 37°C, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained for RSV antigen. The percentage of infected cells was determined by flow cytometry. (a) illustrates the results are expressed as mean ± SD of four independent experiments. ▪ macrophages; □ dendritic cells. (b) illustrates a histogram obtained with DCs at a MOI of 3 and (c) a histogram obtained with macrophages at a MOI of 3. The shaded histograms represent the controls stained with irrelevant biotinylated goat antibody.

Phenotypic changes induced by RSV infection

To analyse whether the effect of RSV infection alters cell surface expression of markers involved in antigen presentation and T cell interaction, macrophages and DCs were infected with RSV at a MOI of 1 and the cell surface expression of antigen presenting, costimulatory and adhesion molecules was examined. RSV-infected macrophages as well as DCs showed enhanced expression of MHC class I, MHC class II, CD80, CD86, CD83 and CD40. No changes in CD54 and CD18 were observed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Expression of surface markers in RSV infected cells.

| Macrophages | Dendritic cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RSV-infected | Control | RSV-infected | |

| MHC-I | 395 ± 57† | 720 ± 458 | 326 ± 134 | 437 ± 161 |

| MHC-II | 338 ± 185 | 464 ± 228 | 868 ± 576 | 1444 ± 317 |

| CD80 | 26 ± 3 | 39 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 | 82 ± 22 |

| CD86 | 42 ± 8 | 109 ± 81 | 84 ± 32 | 230 ± 77 |

| CD83 | 38 ± 7 | 50 ± 11 | 132 ± 33 | 330 ± 44 |

| CD40 | 58 ± 18 | 106 ± 20 | 57 ± 37 | 97 ± 40 |

| CD54 | 114 ± 27 | 125 ± 12 | 185 ± 23 | 185 ± 16 |

| CD18 | 80 ± 5 | 83 ± 12 | 161 ± 15 | 163 ± 18 |

Mean fluorescence intensity.

Release of mediators upon viral infection

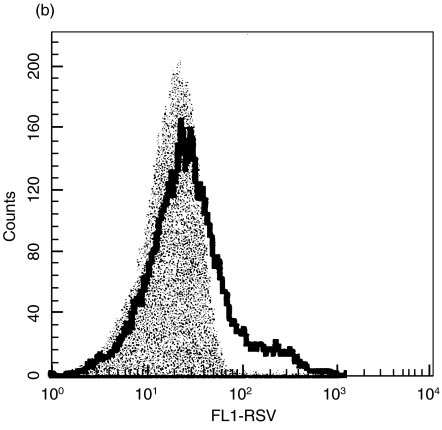

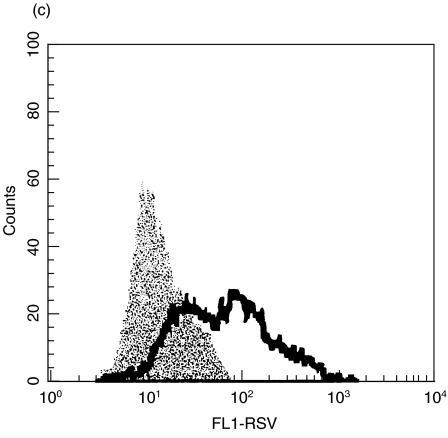

Next, we analysed the kinetics and the profile of mediators generated by macrophages and DCs during RSV infection. Cell culture supernatants were collected at different time points after the infection. Cytokine levels were determined by ELISA and PGE2 concentrations by GC-MS (Fig. 2). Macrophages infected with RSV showed enhanced production of IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, and PGE2. Some differences in the kinetics were seen. In fact, IL-10 and IL-11 production was fast and evident already at 6–16h after infection, while PGE2 steadily increased up to 24 or 48h after infection. A clearly different situation was observed in RSV-infected DCs, which produced low, but reproducible, levels of IL-12 p75 but only low amounts of IL-10. In contrast, IL-6, IL-11 and PGE2 were generated similarly to macrophages (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of cytokine production following RSV-infected DCs and macrophages. Cells were infected with RSV at a MOI of 1 and supernatants were collected at different time points after infection and analysed with specific ELISA or GC-MS. The results represent the means ± SD of six separate experiments.

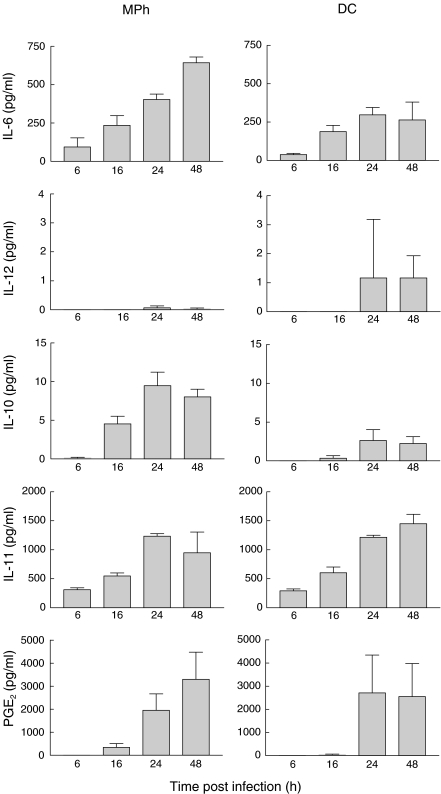

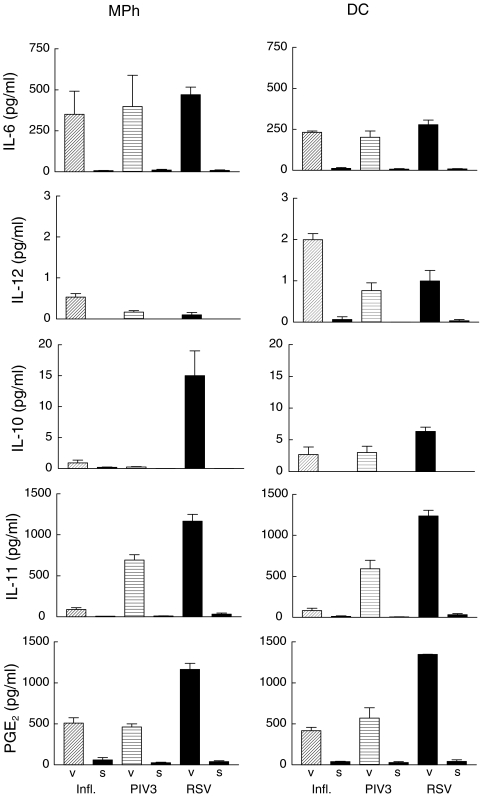

To investigate whether the cytokine profile is specific for RSV we analysed the profile of cytokine secretion during infection with RSV, PIV3 and influenza at a MOI of 1 (Fig. 3). In parallel, cells were treated with ultracentrifuged supernatants free of viral particles as controls. While the control supernatants did hardly induce any cytokine production, all three live virus infections induced a considerable IL-6 production in macrophages as well as DCs. Dendritic cells stimulated by influenza virus produce the highest amount of IL-12p75. In contrast IL-10 is induced predominantly by RSV in macrophages as well as in DCs. High concentrations of IL-11 are produced by macrophages as well as dendritic cells stimulated with RSV and with PIV3, whereas influenza virus induced only low concentrations of IL-11. Likewise, RSV induces the highest concentrations of PGE2.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different viruses on cytokine production from DCs and macrophages. Cells were treated with influenza virus (infl.), parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV3) or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and supernatants were collected after 24 h and analysed with specific ELISA or GC-MS. The results represent the means ± SD of six independent experiments. ‘V’ denotes results from cultures treated with virus and ‘S’ the results from cultures treated with virus free ultracentrifuged supernatants.

Effect of UV irradiation

To further evaluate the mechanism, which might be involved in the stimulation of cytokine secretion, we compared the stimulatory capacity of intact virus with UV inactivated virus. Only active but not UV inactivated virus was able to stimulate IL-12p75 generation in dendritic cells. In contrast, active virus as well as inactivated virus induced IL-11 and PGE2 in both macrophages and dendritic cells (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of UV radiation

| Macrophages | Dendritic cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RSV-UV | RSV | Control | RSV-UV | RSV | |

| IL-6 | 9·0 ± 3·1† | 284 ± 28 | 350 ± 142 | 8·0 ± 2·3 | 271 ± 31 | 231 ± 9 |

| IL-12p75 | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 0·05 ± 0·01 | 0·10 ± 0·08 | 0·03 ± 0·03 | 0·1 ± 0·02 | 1·20 ± 0·25 |

| IL-10 | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 1·1 ± 0·53 | 15·0 ± 4·04 | 0·0 ± 0·0 | 3·18 ± 1·22 | 6·33 ± 0·66 |

| IL-11 | 31·6 ± 13·3 | 971 ± 49 | 1166 ± 83 | 33·3 ± 12·1 | 1023 ± 97 | 1236 ± 69 |

| PGE2 | 41·0 ± 9·8 | 1003 ± 130 | 1166 ± 73 | 43·3 ± 18·5 | 1203 ± 41 | 1346 ± 44 |

pg/ml.

DISCUSSION

Clinical and experimental data demonstrate that respiratory syncytial virus interacts with antigen presenting cells. To investigate the effects of the initial interactions between RSV and macrophages or DCs, we used in vitro cultured human cord blood derived DCs and macrophages. Both cell types were infected by RSV although macrophages appeared to be more active than dendritic cells to internalize virus.

We extended our analysis to the expression of cell surface markers (Table 1). DCs and macrophages infected with RSV expressed high levels of costimulatory and adhesion molecules following RSV infection. A significant increase of MHC class II was observed. The up-regulation of these surface markers in infected cells underlines the capacity of antigen presenting cells to mature following RSV infection, which correlates with the acquired ability to present antigen to T lymphocytes. Thus, our results suggest that RSV infection induces a direct activation and maturation of antigen presenting cells followed by enhanced presentation of antigen and enhanced capacity to stimulate T cells.

Production of cytokines is essential for modulation of the host immunity against RSV. Expression of immunoregulatory cytokines was therefore analysed in supernatants obtained from macrophages and DCs infected with RSV and compared with supernatants obtained after infection with PIV3 and influenza virus. In agreement with previous results [12,13], all three viruses induced IL-6 in macrophages as well as DCs. It has been show that symptoms and fever in natural viral infections correlate with the release of IL-6 [14] and plays a role in induction of protective immunity against the offending virus [15].

All three viruses induced IL-12p75 production by dendritic cells but not by macrophages. IL-12p75 will enhance specific Th1 immune response and thus protective cellular immunity against viral infection. Influenza virus, which induced the highest amount of IL-12p75, is known to induce Th1 cells in vivo[16] and in vitro[17]. IL-12p75 as indicated by our results seems also to play a role in RSV-induced disease. In a clinical study of infants with RSV bronchiolitis a highly significant inverse correlation was found between disease severity and production of IL-12p75 by peripheral monocytes [5]. In mice infected with RSV, IL-12p75-activated NK cells express high levels of IFN-γ and inhibited lung eosinophilia without causing illness [18].

It has been shown before that in vivo monocytes from infants with RSV infection displayed an increased IL-10 generation [6]. A striking result of our study is the high generation of IL-10 release in particular in macrophages induced by RSV but not by influenza or parainfluenza virus. IL-10 has been shown to mitigate inflammatory responses through a variety of mech-anisms [19]. It is conceivable that an up-regulation IL-10 production during RSV infections is one of the reasons for the limited immunity to RSV.

The two other mediators tested, IL-11 and PGE2, were produced abundantly by macrophages as well as DCs. It is known that these mediators exert inhibitory effects on DCs as well as T-cells. IL-11 production following RSV infection of DCs is a novel finding. IL-11 has been detected before in nasal aspirates from RSV infected infants [9] and in biopsies from adult asthmatics [20]. The generation of IL-11 has been attributed to epithelial cells. Epithelial cell lines are able to secrete IL-11 [9] and the epithelium of asthmatics expresses IL-11 mRNA [20]. Overexpression of this cytokine in the bronchial epithelium of transgenic mice results in a remodelling of the airways and the development of airway hyperresponsiveness and airway obstruction [21]. These alterations mimic important pathologic and physiologic changes in the airways of asthmatic patients. Recently, a long lasting change in forced expiratory volume has been found in children suffering from RSV infection during infancy [2]. This change might be due to the enhanced generation of IL-11. In addition, IL-11 exerts a strong anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in vivo. By inhibiting nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB [22], IL-11 reduces production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-, IL-1 and IL-12 by macrophages [22–24]. Generation of IL-11 by DCs as described in this report will have further implications. DCs are known to emigrate to afferent lymph and traffic to draining lymph nodes for T-cell activation after antigen exposure and uptake at peripheral tissue sites [7]. Polarization of naive T-cells might be modulated by IL-11 inasmuch as Curti et al.[25] were able to show that IL-11 directly prevented Th1 polarization and favoured Th2 polarization of highly purified naïve T-cells. In control experiments, IL-11 generation was also induced by infection with PIV3 but not by infection with Influenza virus. Interestingly, PIV3 shares many clinical and immunological features with RSV [26]. PIV3 is a respiratory tract pathogen and primary infection occurs during infancy and early childhood [27]. In addition, PIV3 has the ability to reinfect individuals within a short time interval [28,29], it modulates T-cell responses [30] and at least in animal models it enhances allergic sensitization [31]. There was however, a difference between RSV and PIV3 with regard to a higher generation of PGE2 generation induced by RSV. PGE2 promotes maturation of immature DCs to CD83 positive DCs, which produce only low amounts of IL-12p75 and bias the development of naive T-cells toward the production of Th2-type cytokines [32]. In addition, PGE2 is known to inhibit T-cell activation directly by suppression of IL-2 synthesis [33].

In order to elucidate the mechanisms leading to RSV mediated cytokine generation, we used in addition to active virus, UV inactivated virus attaching to the cell surface. Interestingly, attachment by UV inactivated virus alone elicited generation of IL-11 and PGE2 in macrophages as well as DCs but no IL-10 and IL-12p75.

Taken together, it is conceivable that in addition to IL-10 production by macrophages IL-11 and PGE2 generation by DCs in vivo might contribute to the predominance of Th2 cells found in ongoing RSV induced bronchiolitis [16,34,35] and thus might be responsible for the delayed protective RSV specific immune response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (01GC9801). We thank B. Watzer, Children's Hospital, Philipps University Marburg, Germany for the determination of PGE2 and Dr J. Gregersen, Chiron Behring Marburg, Germany for providing Influenza and Parainfluenza virus and MDCK cells.

The expert technical assistance of Veronika Baumeister and Angelika Michel is acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simoes EA. Respiratory syncytial virus infection. Lancet. 1999;354:847–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein RT, Sherrill D, Morgan WJ, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Taussig LM, Wright AL, Martinez FD. Respiratory syncytial virus in early life and risk of wheeze and allergy by age 13 years. Lancet. 1999;354:541–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigurs N, Bjarnason R, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1501–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall CB, Walsh EE, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:693–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bont L, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, van Vught AJ, Kimpen JL. Monocyte interleukin-12 production is inversely related to duration of respiratory failure in respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1772–5. doi: 10.1086/315433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bont L, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A, van Aalderen WM, Brus F, Draaisma JT, Geelen SM, Kimpen JL. Monocyte IL-10 production during respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis is associated with recurrent wheezing in a one-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1518–23. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9904078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt PG, Stumbles PA. Regulation of immunologic homeostasis in peripheral tissues by dendritic cells: the respiratory tract as a paradigm. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:421–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Midulla F, Huang YT, Gilbert IA, Cirino NM, McFadden ER, Jr, Panuska JR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human cord and adult blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:771–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einarsson O, Geba GP, Zhu Z, Landry M, Elias JA. Interleukin-11. stimulation in vivo and in vitro by respiratory viruses and induction of airways hyperresponsiveness. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:915–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI118514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thurau AM, Streckert HJ, Rieger CH, Schauer U. Increased number of T cells committed to IL-5 production after respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection of human mononuclear cells in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:450–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweer H, Watzer B, Seyberth HW, Nusing RM. Improved quantification of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha and F2-isoprostanes by gas chromatography/triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometry: partial cyclooxygenase-dependent formation of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha in humans. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:1362–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199712)32:12<1362::AID-JMS606>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bender A, Amann U, Jager R, Nain M, Gemsa D. Effect of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor on human monocytes infected with influenza A virus. Enhancement of virus replication, cytokine release, and cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1993;151:5416–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franke-Ullmann G, Pfortner C, Walter P, Steinmuller C, Lohmann-Matthes ML, Kobzik L, Freihorst J. Alteration of pulmonary macrophage function by respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro. J Immunol. 1995;154:268–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser L, Fritz RS, Straus SE, Gubareva L, Hayden FG. Symptom pathogenesis during acute influenza. interleukin-6 and other cytokine responses. J Med Virol. 2001;64:262–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SW, Youn JW, Seong BL, Sung YC. IL-6 induces long-term protective immunity against a lethal challenge of influenza virus. Vaccine. 1999;17:490–6. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz PV, Calhoun WJ, Hinton KL, et al. Differential effects of respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus on mononuclear cell cytokine responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1157–64. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9804075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella M, Salio M, Sakakibara Y, Langen H, Julkunen I, Lanzavecchia A. Maturation, activation, and protection of dendritic cells induced by double-stranded RNA. J Exp Med. 1999;189:821–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussell T, Openshaw PJ. IL-12-activated NK cells reduce lung eosinophilia to the attachment protein of respiratory syncytial virus but do not enhance the severity of illness in CD8 T cell-immunodeficient conditions. J Immunol. 2000;165:7109–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard M, O'Garra A. Biological properties of interleukin 10. Immunol Today. 1992;13:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90153-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minshall E, Chakir J, Laviolette M, Molet S, Zhu Z, Olivenstein R, Elias JA, Hamid Q. IL-11 expression is increased in severe asthma. association with epithelial cells and eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:232–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang W, Geba GP, Zheng T, Ray P, Homer RJ, Kuhn C III, Flavell RA, Elias JA. Targeted expression of IL-11 in the murine airway causes lymphocytic inflammation, bronchial remodeling, and airways obstruction. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2845–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI119113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trepicchio WL, Wang L, Bozza M, Dorner AJ. IL-11 regulates macrophage effector function through the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB. J Immunol. 1997;159:5661–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leng SX, Elias JA. Interleukin-11 inhibits macrophage interleukin-12 production. J Immunol. 1997;159:2161–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redlich CA, Gao X, Rockwell S, Kelley M, Elias JA. IL-11 enhances survival and decreases TNF production after radiation- induced thoracic injury. J Immunol. 1996;157:1705–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curti A, Ratta M, Corinti S, et al. Interleukin-11 induces Th2 polarization of human CD4 (+) T cells. Blood. 2001;97:2758–63. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plotnicky-Gilquin H, Cyblat D, Aubry JP, Delneste Y, Blaecke A, Bonnefoy JY, Corvaia N, Jeannin P. Differential effects of parainfluenza virus type 3 on human monocytes and dendritic cells. Virology. 2001;285:82–90. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed G, Jewett PH, Thompson J, Tollefson S, Wright PF. Epidemiology and clinical impact of parainfluenza virus infections in otherwise healthy infants and young children <5 years old. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:807–13. doi: 10.1086/513975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marx A, Gary HE, Jr, Marston BJ, et al. Parainfluenza virus infection among adults hospitalized for lower respiratory tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:134–40. doi: 10.1086/520142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welliver R, Wong DT, Choi TS, Ogra PL. Natural history of parainfluenza virus infection in childhood. J Pediatr. 1982;101:180–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sieg S, Muro-Cacho C, Robertson S, Huang Y, Kaplan D. Infection and immunoregulation of T lymphocytes by parainfluenza virus type 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6293–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riedel F, Krause A, Slenczka W, Rieger CH. Parainfluenza-3-virus infection enhances allergic sensitization in the guinea-pig. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996;26:603–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalinski P, Schuitemaker JH, Hilkens CM, Kapsenberg ML. Prostaglandin E2 induces the final maturation of IL-12-deficient CD1a+CD83+ dendritic cells: the levels of IL-12 are determined during the final dendritic cell maturation and are resistant to further modulation. J Immunol. 1998;161:2804–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rappaport RS, Dodge GR. Prostaglandin E inhibits the production of human interleukin 2. J Exp Med. 1982;155:943–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smyth RL, Fletcher JN, Thomas HM, Hart CA. Immunological responses to respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:210–14. doi: 10.1136/adc.76.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roman M, Calhoun WJ, Hinton KL, Avendano LF, Simon V, Escobar AM, Gaggero A, Diaz PV. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants is associated with predominant Th-2-like response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:190–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9611050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]