Abstract

The objective of the study was to evaluate the NO-producing potential of synovial fluid (SF) cells. SF from 15 patients with arthritis was compared with blood from the same individuals and with blood from 10 healthy controls. Cellular expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) was analysed by flow cytometry. High-performance liquid chromatography was used to measure l-arginine and l-citrulline. Nitrite and nitrate were measured colourimetrically utilizing the Griess’ reaction. Compared to whole blood granulocytes in patients with chronic arthritis, a prominent iNOS expression was observed in SF granulocytes (P < 0·001). A slight, but statistically significant, increase in iNOS expression was also recorded in lymphocytes and monocytes from SF. l-arginine was elevated in SF compared to serum (257 ± 78 versus 176 ± 65 µmol/l, P = 0·008), whereas a slight increase in l-citrulline (33 ± 11 versus 26 ± 9 µmol/l), did not reach statistical significance. Great variations but no significant differences were observed comparing serum and SF levels of nitrite and nitrate, respectively, although the sum of nitrite and nitrate tended to be elevated in SF (19·2 ± 20·7 versus 8·6 ± 6·5 µmol/l, P = 0·054). Synovial fluid leucocytes, in particular granulocytes, express iNOS and may thus contribute to intra-articular NO production in arthritis.

Keywords: arthritis, granulocytes, iNOS, nitric oxide

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown aetiology. Genetic, immunological and hormonal as well as external environmental factors are believed to have important roles in the aetiopathogenesis of RA [1–3]. Large numbers of polymorphonuclear neutrophilic granulocytes are recruited to the rheumatoid joint, but interest in their contribution to articular inflammation and destruction has been overshadowed by the great interest for the pathogenic roles of T cells and macrophages [1,4,5].

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous free radical synthesized, via l-arginine oxidation to l-citrulline, by a family of nitric oxide synthases (NOS). Isoforms of NOS are either constitutional (e.g. neuronal cNOS and endothelial cNOS), or inducible (iNOS). The cNOS isoforms are vital in regulation of circulation and nerve function. iNOS can be expressed in various cell types after exposure to proinflammatory cytokines [6]. Once induced, iNOS produces significant and sustained amounts of NO where l-arginine availability is considered the most important regulatory pathway. High output of NO is a non-specific microbicidal pathway as well as proinflammatory and damaging to surrounding cells [7].

Several pathways of NO metabolism have been described. In the presence of oxygen, NO rapidly forms nitrite and nitrate. Reactions with other reactive oxygen intermediates can yield peroxynitrite and subsequently hydroxyl radicals. NO can also react with proteins, either directly by nitrosylation or by reacting with free thiol groups to form S-nitrosothiol compounds, e.g. S-nitrosoalbumin and S-nitrosoglutathione. These compounds are significantly more stable than NO and can retain NO-like properties for several hours [8].

Increased production of NO has been implicated in several inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren's syndrome [8]. It has been shown in animal arthritis models that suppression of NO production can have profound effects on disease initiation and progression [9–12]. In humans, a relationship has been shown between serum NO levels and disease activity in RA [13]. In RA, chondrocytes, fibroblasts, synoviocytes, macrophages and lymphomononuclear cells in blood and synovial fluid have been shown to produce NO or to express iNOS [14,15]. Synovial fluid cells have not been studied to any great extent, and the published results are contradictory. Grabowski et al. could not demonstrate iNOS mRNA in synovial fluid cells [16], whereas Borderie et al. [17] reported expression of iNOS in lymphomononuclear cells in arthritic synovial fluid.

The aim of this study was to evaluate NO-producing abilities by blood and joint fluid leucocytes as reflected by the expression of iNOS. We also analysed the NO precursor l-arginine, and end products nitrate, nitrite and l-citrulline in synovial fluid and blood from the same patients and in blood samples from control subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Synovial fluid (obtained by therapeutic knee joint aspiration) and blood samples was collected from 15 patients with arthritis, age 45 ± 16 years (Table 1). All patients were recruited after informed consent. The 11 patients with a diagnosis of RA fulfilled the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (formerly, the American Rheumatism Association) [18]. Blood samples were also collected from 10 volunteers (department staff, eight women and two men, age 42 ± 14 years). All blood samples were drawn into heparinized tubes at room temperature. Synovial fluid samples were collected in sterile tubes without additives. Cell preparation was always performed within 45 min.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patient material

| Patient number | Age (years) | Gender | Diagnosis | Disease duration (years) | Medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | RA− | 10 | MTX 15 mg/wPre 2·5 mg/day |

| 2 | 53 | F | RA− | 25 | None |

| 3 | 47 | M | RA+ | 12 | None |

| 4 | 56 | M | RA+ | 40 | Pre 12·5 mg/day |

| 5 | 28 | M | JCA | 10 | Pre 5 mg/day |

| 6 | 60 | F | RA+ | 8 | SSZ 2 g/dayPre 7·5 mg/day |

| 7 | 50 | F | RA+ | 13 | MTX 10 mg/wCSA 100 mg/day MP 16 mg/day |

| 8 | 63 | M | RA+ | 15 | Aur 9 mg/day |

| 9 | 42 | M | RA+ | 25 | Lef 20 mg/day |

| 10 | 58 | F | RA- | 20 | MTX 12·5 mg/wPre 1·25 mg/day |

| 11 | 20 | F | JCA | 18 | None |

| 12 | 40 | F | RA+ | 5 | Aur 6 mg/day |

| 13 | 69 | F | RA+ | 33 | Aza 100 mg/dayPre 25 mg/day |

| 14 | 22 | F | JCA | 20 | MTX 15 mg/wPre 1·25 mg/day |

| 15 | 31 | F | PsoA | 1 | MTX 15 mg/w |

MTX = methotrexate, SSZ = sulphasalazine, CSA = ciclosporin, Aur = auranofin, Lef = leflunomide, Aza = azathioprine, Pre = prednisolone, MP = methyl prednisolone, RA + = seropositive RA, RA− = seronegative RA, JCA = juvenile chronic arthritis, PsoA = psoriatic arthritis

Cell preparation

A commercially available staining kit was used (Intrastain®, DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark). Blood samples and synovial fluid (50 µl), without consideration of the cell concentration, were fixed as described by the manufacturer. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7·3), and centrifugation (300 g, 5 min), the cell pellets were permeabilized and erythrocytes lysed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

iNOS determination

Cells were incubated for 15 min with fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated iNOS-specific polyclonal rabbit IgG antibodies raised against the amino terminus of human iNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and analysed immediately by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Ten thousand events were counted from each sample. Different cell populations were identified by their appearance in the forward/side scatter diagram and phycoerythrin-labelled anti-CD antibodies (Immunotech, Marseille, France). CD15+ cells were identified as neutrophils, CD14+ as monocytes, T and B lymphocytes as CD3+ and CD19+ cells, respectively. Proportions of the cell populations were controlled to avoid statistical errors. Non-antibody binding of IgG was assessed by stain with FITC-labelled polyclonal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz). A 50-fold excess of non-labelled polyclonal rabbit IgG (Dako) was given prior to incubation with the anti-iNOS antibody in order to block non-specific and/or Fc-mediated binding of the antibody. Furthermore, to demonstrate the specificity of the anti-iNOS antibody, preabsorption experiments were performed with a fivefold excess of its specific blocking peptide (Santa Cruz).

Comparison of anti-iNOS antibodies

Because iNOS in human neutrophils is firmly membrane-bound and because there are considerable differences between different detergents regarding their ability to solubilize iNOS [19], we compared two different anti-iNOS-antibodies directed against different epitopes. This comparison was made on exudated neutrophils resuspended to a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml. Permeabilization/fixation was performed either by Intrastain® or by the combination of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and different concentrations (0·02–0·5%) of saponin (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA). The samples were then incubated for 15 min with different concentrations of either of four different FITC-labelled Ig/antibody preparations, i.e. polyclonal rabbit IgG anti-iNOS antibodies, polyclonal rabbit IgG, monoclonal mouse IgG1 anti-iNOS antibodies (Santa Cruz) or polyclonal mouse IgG (Santa Cruz). After washing, the stained cells were counted by flow cytometry.

Nitrate/nitrite determination

Heparin plasma and cell-free synovial fluid supernatants (centrifuged 2600 g, 5 min) were stored at −70°C awaiting nitrite/nitrate analyses. All nitrite/nitrate analyses were performed simultaneously. In order to avoid absorbance disturbances due to the presence of proteins, all plasma and synovial fluid samples (200 µl) were placed in a Por-SPECTRUM® membrane (Spectrum Companies, Gardena, CA, USA), and dialysed against 800 µl of PBS overnight. Ten µl of the protein-free dialysate was incubated with 10 µl 1 mm NADPH (Sigma) in PBS and 1% (v/v) nitrate reductase (10 U/ml; Boehringer-Mannheim Scandinavia AB, Bromma, Sweden) at 37°C for 30 min. This mixture was used for the Griess assay of nitrite by adding 244 µl sulphanilamide in 0·1 m HCl (Merck & Co Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). After 10-min incubation, 26 µl naphtylethylendiamine (1 mg/ml H2O; Fluka, Milwaukee, WI, USA) was added. The 540-nm absorption was read after 30 min with a DU 68 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA). The detection limit was 1 µmol/l using this method.

l-arginine/l-citrulline determinations

A slight modification of the method described by Meyer et al. [20] was used to measure l-arginine and l-citrulline. After filtration (Microcon YM-3, Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA), 600 µl of the plasma or synovial fluid samples were reacted with 400 µl o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) reagent (Sigma) for 2 min at room temperature in order to obtain fluorescent derivatives of l-arginine and l-citrulline. Prior to derivatization, the OPA reagent had been supplemented with 1 µl mercaptoethanol. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)/fluorescence detection analysis was carried out using a Kontron HPLC equipped with an autosampler (Tegimenta AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) and a Shimadzu Model RF-535 fluorescence detector (Kyoto, Japan). The HPLC column (LiChrospher 100 RP-18, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was eluted isocratically with 10 mm KH2PO4 (pH 5·8)/acetonitrile/methanol/tetrahydrofuran in the following proportions: 80/9·5/9·5/1 at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, followed by 5 min wash with 10 mm KH2PO4/acetonitrile/methanol/tetrahydrofuran (50/24/24/2). The amount of l-arginine and l-citrulline was calculated on the basis of the peak height relative to a standard curve on a PC-Integration system.

Determinations of nitrite/nitrate and l-arginine/l-citrulline were performed on the nine patients first included. These samples were analysed at the same occasion together with the 10 controls.

Statistics

The Wilcoxon sign rank and rank sum test, Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-tests were used. P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

RESULTS

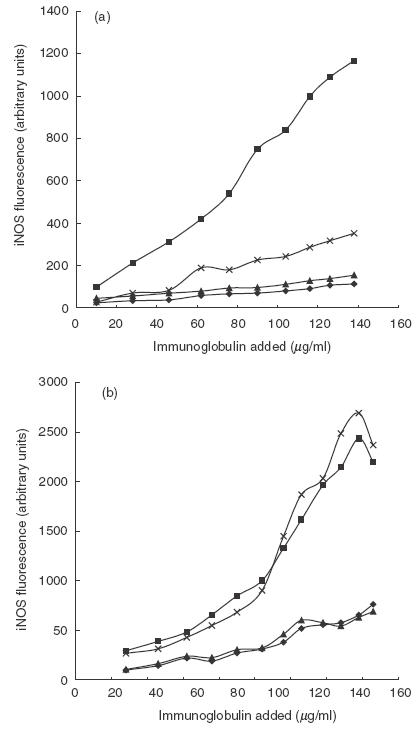

Figure 1 illustrates the binding characteristics of polyclonal rabbit anti-iNOS and monoclonal mouse anti-iNOS antibodies to exudated human polymorphonuclear granulocytes. Compared to the rabbit antibody, specific for an epitope at the aminoterminus of iNOS, the monoclonal mouse antibody directed to an epitope at the C-terminus bound poorly to cells prepared with Intrastain® (Fig. 1a). Using cells permeabilized with 0·1% saponin, however, the binding of the mouse monoclonal anti-iNOS antibody was equally efficient to the polyclonal rabbit antibody (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Fluorescence after labelling of exudated polymorhonuclear leucocytes with different concentrations of antibodies/Ig. (a) Fixation and permeabilization with Intrastain®. (b) Samples are fixed and permeabilized with PFA 4% and saponin 0·1%, respectively. ♦, Polyclonal rabbit IgG; ▪, polyclonal rabbit IgG anti-iNOS; ▴, polyclonal mouse IgG; ×, monoclonal mouse IgG anti-iNOS.

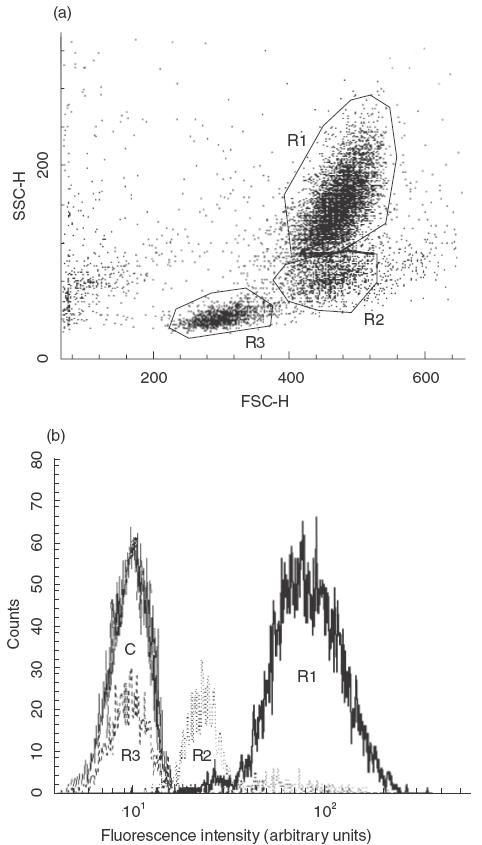

Figure 2 illustrates a typical cytofluorometrical analysis of synovial fluid. From forward and side scatter it was possible to identify three distinct cell populations consisting of granulocytes (R1), monocytes (R2) and lymphocytes (R3). Gating as shown in Fig. 2a revealed clear-cut differences in fluorescence intensity. The degree of iNOS expression was highest in the granulocytes, followed by monocytes and lymphocytes (Fig. 2b). The differences in iNOS expression among the cell populations were also confirmed by gating for CD3, CD14, CD 15 and CD19, where the CD15+ cells were clearly iNOS+.

Fig. 2.

A representative example of flow cytometric iNOS expression in different cell populations in synovial fluid (patient number 9). (a) Forward/side scatter plot providing cell size versus granularity. The cell populations were gated and the resulting fluorescence profiles are shown in (b). The granulocyte population is clearly iNOS+ while mononuclear cells show lower iNOS expression. R1 represents granulocytes, R2 monocytes and R3 lymphocytes. C is FITC-labelled rabbit IgG in an R1-gating (granulocyte population).

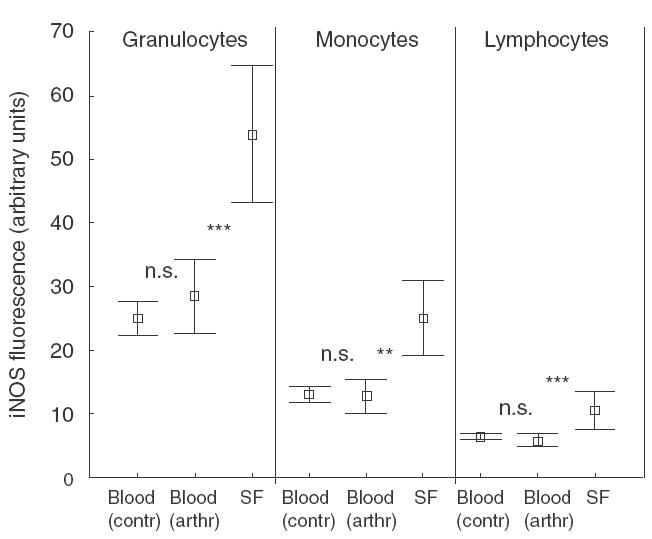

The fluorescence achieved by staining for iNOS was equally low in blood granulocytes from the controls and patients (Fig. 3). Statistically significant induction of granulocyte iNOS was seen in synovial fluid compared to blood cells (P < 0·001). This finding was consistent in all arthritis patients. Similarly, statistically significant differences in iNOS expression were observed in the monocyte/lymphocyte populations when comparing synovial fluid with blood, although less pronounced than in the granulocytes.

Fig. 3.

iNOS expression in different cell populations from control blood (n =10), patient blood (n =15) and synovial fluid (n =15). All synovial fluid leucocyte populations show statistically significant iNOS expression compared to the corresponding cell population in blood. *** =P < 0.001; ** =P < 0.01. Mean values ± standard deviations are given.

FITC-labelled normal rabbit IgG did not give rise to significant fluorescence of blood or synovial fluid cells, and binding of iNOS-specific rabbit IgG was not blocked by an excess of normal rabbit IgG (not illustrated). Preabsorption of anti-iNOS antibody with blocking peptide inhibited iNOS fluorescence by 60% (range 40–100%, not illustrated). No proportional disturbances between the different cell populations in blood versus synovial fluid were noted.

Non-permeabilized cells were not stained by anti-iNOS antibodies.

Nitrite levels were significantly lower in patient plasma (n =9) compared to plasma from control subjects (n =10) (9·1 ± 3·5 µmol/l versus 14·5 ± 3·3, mean ± s.d., P =0·003). Synovial fluid nitrite levels (9·0 ± 5·9 µmol/l) did not differ significantly from patient plasma. Measurements of the sum of nitrite/nitrate showed large variations in the patients as well as in the controls. Here too, patients had significantly lower levels in plasma than controls (8·6 ± 6·5 versus 28·5 ± 22 µmol/l, P =0·007). The sum of nitrite/nitrate concentrations in synovial fluid varied considerably and a tendency towards higher levels in synovial fluid compared to plasma did not quite reach statistical significance (19·2 ± 20·7 versus 8·6 ± 6·5 µmol/l, P =0·054). Furthermore, the levels of nitrite and nitrate did not correlate to the expression of iNOS.

l-arginine was significantly lower in plasma from arthritic patients (n =9) (176 µmol/l ±65) compared to controls (n =10) (237 ± 39, P =0·022), whereas synovial fluid (n =9) (257 ± 78) exhibited significantly higher levels compared to patient plasma (P =0·015). A similar pattern was observed for l-citrulline, but here the differences did not reach statistical significance (controls 31·3 µmol/l ± 2·7; patient blood 26·2 ± 8·9; synovial fluid 33·4 ± 11·4). A weak correlation (0·55; P =0·12) was observed between l-arginine levels in synovial fluid and blood. Synovial fluid levels of l-citrulline, on the other hand, showed no correlation with blood levels (− 0·002; P =0·995).

DISCUSSION

Although the initial clinical focus of this study was rheumatoid arthritis, we also chose to include a few patients with other diagnoses, as similar results were obtained in all inflammatory synovial fluids tested, regardless of the type of arthritis. Hence, the main finding was the up-regulation of iNOS in synovial fluid granulocytes compared to blood granulocytes in patients with chronic arthritis. This has not been reported previously.

By immunostaining of biopsy specimens from patients with rheumatoid arthritis iNOS has been demonstrated in synovial lining cells, synovial fibroblasts, macrophages, chondrocytes, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, but not in lymphocytes or neutrophils [21–23]; nor did Grabowski et al. find iNOS mRNA expression or NO production by unstimulated or cytokine-stimulated synovial fluid leucocytes [16]. However, since the expression of iNOS m-RNA is short-lived [24], we believe that protein detection is preferable. Studies on cell cultures from inflamed joints introduces an evident selection bias which may lead to erroneous conclusions, because cell culturing results in loss of non-dividing cells such as neutrophils [4].

By means of flow cytometry, Borderie et al. [17] reported iNOS expression in monocytes as well as in lymphocytes, but not in granular cells in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Using a similar approach, comparing blood and synovial fluid cells, we could confirm the expression of iNOS in synovial fluid monocytes, and also faintly in lymphocytes. However, the most striking finding was the obvious up-regulation of iNOS in synovial fluid granulocytes both compared to circulating cells, and in comparison with synovial fluid lymphomononuclear cells. The explanation for the discrepant results concerning granulocyte iNOS expression in arthritis is not obvious, but should be sought in methodological differences such as fixation/permeabilization, and the use of different anti-iNOS antibodies. We could demonstrate that the granulocyte binding of a monoclonal mouse antibody directed against the carboxyterminus of iNOS was dependent on the permeabilization method used. Thus, a commercial permeabilization/fixation kit did not allow iNOS detection by this antibody, whereas this was achieved by cell permeabilization/fixation with a saponin/paraformaldehyde. This could, hypothetically, depend on exposure of a hidden (membrane-bound?) iNOS epitope achieved by the latter method. Others have shown that the method of membrane solubilization is essential for the release of membrane-bound iNOS from human neutrophil granulocytes [19].

Although contrary to the results of others, our demonstration of iNOS in synovial fluid granulocytes is not surprising considering that neutrophil iNOS expression has been shown in many other inflammatory conditions [25–30]. In subsequent studies we have also been able to confirm the occurrence of granulocyte iNOS by Western blot analysis (to be published). Neutrophilic granulocytes have the most destructive potential of all cells within the rheumatoid joint and, as pointed out by Edwards and Hallet [4], their role in rheumatic joint destruction has probably been underestimated. The predominance of neutrophils in synovial fluid is well known, but they also invade the synovium and possess the ability to directly invade cartilage and attack chondrocytes within the lacunae [31–33]. Bone destruction in RA may, at least in part, be caused by enhanced production of immature neutrophils [34]. Furthermore, neutrophils are capable of degrading intact cartilage, proteoglycans and collagens [35,36].

Several investigators have shown increased nitrite concentrations in synovial fluid [17,37–39], a finding not reproduced in the present study. In order to avoid protein interference in the Griess assay of nitrite, we chose to perform the analyses in protein-free dialysates of serum and synovial fluid. Unfortunately, the nitrite concentrations in the dialysates were too close to the detection limit to allow reliable conclusions to be drawn, although we did indeed find a tendency towards increased sum of nitrite/nitrate in synovial fluid.

Accessibility of l-arginine is of fundamental importance for the production of NO, because it is the substrate for NO production. Once induced, iNOS is considered a high-output enzyme and will generate NO as long as l-arginine is available. Consumption of l-arginine by arginases thus down-regulates the production of NO [40]. In the present study we found subnormal levels of l-arginine in plasma in arthritic patients compared to controls. The levels of l-arginine in synovial fluid, however, were higher than in plasma of the arthritic patients. The plasma levels of l-arginine in the controls were within the same magnitude as reported by others [41]. We are not aware of any previous studies where l-arginine has been analysed in synovial fluid. Elevated l-citrulline in synovial fluid without correlation to blood levels may be a result of local metabolism and NO production, but here the differences did not reach statistical significance. The finding of elevated l-arginine in synovial fluid is more surprising. This could, hypothetically, be due to local protein catabolism, but may also represent an active production or even transport of l-arginine into synovial fluid. It is known that enzymes responsible for the conversion of l-citrulline back to l-arginine can be activated in certain inflammatory situations [42]. Regardless of the cause, our study demonstrate that the substrate for NO production is present in high concentrations in synovial fluids from patients with arthritis.

In conclusion, we found that iNOS is expressed in granulocytes exudated into arthritic joints. We also showed that prerequisites for NO-production exist in synovial fluid, as both leucocyte iNOS and l-arginine are present. Our results also support the notion of local production of NO in the joints of patients with arthritis. Based upon these findings we conclude that synovial fluid leucocytes, in particular granulocytes, may contribute to NO production in arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the county council of Östergötland, the University Hospital's Research Funds, King Gustav V 80 years foundation and the Swedish Association Against Rheumatism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. T-cell responses in rheumatoid arthritis: systemic abnormalities – local disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:210–7. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yocum DE. Pathogenic cells and therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999;29:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(99)80035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masi AT, Bijlsma JWJ, Chikanza IC, Pitzalis C, Cutolo M. Neuroendocrine, immunologic, and microvascular system interactions in rheumatoid arthritis: physiopathogenetic and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999;29:65–81. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(99)80039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards S, Hallet M. Seeing the wood for the trees: the forgotten role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:320–4. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pillinger MH, Abramson SB. The neutrophil in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995;21:691–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases. structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boucher JL, Moali C, Tenu JP. Nitric oxide biosynthesis, nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and arginase competition for l-arginine utilization. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:1015–28. doi: 10.1007/s000180050352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clancy RM, Amin AR, Abramson SB. The role of nitric oxide in inflammation and immunity. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1141–51. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1141::AID-ART2>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miesel R, Kurpisz M, Kroger H. Suppression of inflammatory arthritis by simultaneous inhibition of nitric oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawand NB, Willis WD, Westlund KN. Blockade of joint inflammation and secondary hyperalgesia by L-NAME, a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Neuroreport. 1997;8:895–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor JR, Manning PT, Settle SL, et al. Suppression of adjuvant-induced arthritis by selective inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;273:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00672-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Berg WB, van de Loo F, Joosten LA, Arntz OJ. Animal models of arthritis in NOS2-deficient mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:413–5. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueki Y, Miyake S, Tominaga Y, Eguchi K. Increased nitric oxide levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:230–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stichtenoth DO, Frolich JC. Nitric oxide and inflammatory joint diseases. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:246–57. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang D, Murrel GAC. Nitric oxide in arthritis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:1511–9. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski P, Macpherson H, Ralston S. Nitric oxide production in cells derived from the human joint. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:207–12. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borderie D, Hilliquin P, Hernvann A, Kahan A, Menkes CJ, Ekindjian OG. Nitric oxide synthase is expressed in the lymphomononuclear cells of synovial fluid in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2083–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheeler MA, Smith SD, Garcia-Cardena G, Nathan CF, Weiss RM, Sessa WC. Bacterial infection induces nitric oxide synthase in human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:110–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI119121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer J, Richter N, Hecker M. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of nitric oxide synthase-related arginine derivatives in vitro and in vivo. Anal Biochem. 1997;247:11–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabowski PS, Wright PK, Van ‘t Hof RJ, Helfrich MH, Ohshima H, Ralston SH. Immunolocalization of inducible nitric oxide synthase in synovium and cartilage in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:651–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakurai H, Kohsaka H, Liu MF, et al. Nitric oxide production and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in inflammatory arthritides. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2357–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI118292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pozza M, Guerra M, Manzini E, Calzà L. A histochemical study of the rheumatoid synovium: focus on nitric oxide, nerve growth factor high affinity receptor, and innervation. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallerath T, Gath I, Aulitzky WE, Pollock JS, Kleinert H, Förstermann U. Identification of the NO synthase isoforms expressed in human neutrophil granulocytes, megakaryocytes and platelets. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda I, Kasajima T, Ishiyama S, et al. Distribution of inducible nitric oxide synthase in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1339–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singer II, Kawka DW, Scott S, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in colonic epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:871–85. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson FM, Long BW, Tober KL, Ross MS, Oberyszyn TM. Gene expression and cellular sources of inducible nitric oxide synthase during tumor promotion. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2053–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.9.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forster C, Clark HB, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human cerebral infarcts. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1999;97:215–20. doi: 10.1007/s004010050977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeichi O, Saito I, Okamoto Y, Tsurumachi T, Saito T. Cytokine regulation on the synthesis of nitric oxide in vivo by chronically infected human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Immunology. 1998;93:275–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukahara Y, Morisaki T, Horita Y, Torisu M, Tanaka M. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in circulating neutrophils of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and septic patients. World J Surg. 1998;22:771–7. doi: 10.1007/s002689900468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bromley M, Wooley DE. Histopathology of the rheumatoid lesion. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:857–63. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohr W, Westerhellweg H, Wessinghage D. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes in rheumatic tissue destruction. III. An electron microscopic study of PMNs at the pannus cartilage junction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40:396–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.40.4.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohr W, Pelster B, Wessinghage D. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes in rheumatic tissue destruction. Rheumatol Int. 1984;5:39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00541364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohtsu S, Yagi H, Nakamura M, et al. Enhanced neutrophilic granulopoiesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Involvement of neutrophils in disease progression. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1341–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catham WW, Swaim R, Froshin H, Heck LW, Miller EJ, Blackburn WD. Degradation of human articular cartilage by neutrophils in synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:51–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowanko IC, Ferrante A. Adhesion and TNF priming in neutrophil-mediated cartilage damage. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;79:36–42. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farrell AJ, Blake DR, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Increased concentrations of nitrite in synovial fluid and serum samples suggest increased nitric oxide synthesis in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:1219–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.11.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hilliquin P, Borderie D, Hernvann A, Menkes CJ, Ekindjian OG. Nitric oxide as s-nitrosoproteins in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1512–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stichtenoth DO, Fauler J, Zeidler H, Frölich JC. Urinary nitrate excretion is increased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and reduced by prednisolone. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:820–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.10.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bune AJ, Shergill JK, Cammack R, Cook HT. l-arginine depletion by arginase reduces nitric oxide production in endotoxic shock: an electron paramagnetic resonance study. FEBS Lett. 1995;366:127–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00495-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo L, Chapman TE, Sanchez M, et al. Plasma arginine and citrulline kinetics in adults given adequate and arginine-free diets. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:7749–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nathan C, Xie QW. Regulation of biosynthesis of nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13725–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]