Abstract

Anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECA) have been found to play an important role in many vascular disorders. In order to determine the presence of AECA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP), and to elucidate the pathogenic and clinical value of their measurement in this disease, AECA were detected by immunofluorescence staining and a human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC)-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in 20 children with HSP, 10 children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) without vasculitis and 10 normal healthy children. Antibodies against another endothelial cells, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC-d) were also detected by cell-based ELISA. In some experiments, we compared the binding activity of antibodies to HUVEC with and without tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) or interleukin-1 (IL-1) pretreatment. Patients with acute onset of HSP had higher serum levels of IgA antibodies, both against HUVEC and against HMVEC-d, than healthy controls (P = 0·001, P = 0·008, respectively). Forty-five per cent of patients had positive IgA AECA to HUVEC, and 35% had positive IgA AECA to HMVEC-d. The titres of IgA antibodies to HUVEC paralleled the disease activity. After TNF-α treatment, the values of IgA AECA to HUVEC in HSP patients were significantly increased (P = 0·02). For IgG and IgM AECA, there was no difference between HSP patients and controls (P = 0·51, P = 0·91). Ten JRA children without vasculitis had no detectable IgG, IgM or IgA AECA activity. The results of this study showed that children with HSP had IgA AECA, which were enhanced by TNF-α treatment. Although the role of these antibodies is not clear, IgA AECA provide another immunological clue for the understanding of HSP.

Keywords: anti-endothelial cell antibodies, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, TNF-α

INTRODUCTION

Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a systemic form of small vessel vasculitis that primarily affects children. It is characterized by normal platelet count, cutaneous palpable purpura, arthritis or arthralgia, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding and glomerulonephritis [1]. Most patients have symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of disease. Although recurrences occur in more than one-third of patients, HSP is usually self-limited. Renal involvement with progressive functional impairment and bowel perforation are two rare but major complications [2]. Treatment consists of supportive care and anti-inflammation drugs (non-steroid or steroid) [1,2].

The real pathogenesis of HSP is still unknown; however, elevated serum IgA levels, vascular deposition of IgA-contained immune complexes, and the finding of IgA anticardiolipin antibodies suggest the possibility of immune-mediated mechanisms [3–5]. In vasculitis, the endothelial cells forming the interphase between the bloodstream and the vessel wall are the initial sites of vascular damage. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECA), a heterogeneous group of antibodies directed against a variety of antigen determinants on endothelial cells [6,7], have been reported to exist and play a pathogenic role in Kawasaki disease, Wegener's granulomatosis and Takayasu's arteritis [8–12]. To clarify the possible autoimmune processes of HSP, in this study we investigated the presence of antibodies to human endothelial cells in children with acute onset of HSP by the methods of immunofluorescence staining and a cell-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and evaluated and compared the binding activity of AECA to the resting and the cytokine-stimulated endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and controls

Twenty previously healthy Chinese children with acute onset of HSP were included in this study. The diagnosis was confirmed according to the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria [1]. Informed consents and institutional approval were obtained for this study. Patients underwent laboratory and physical investigations at the acute stage and convalescent stage (6–12 months later). Ten normal healthy children were enrolled as controls. Another 10 children with active juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) (four pauciarticular type, four polyarticular and two systemic type), but not complicated with vasculitis, were also recruited in this study. Serum samples of patients and controls were stored at −20°C before testing.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) culture

Endothelial cells were obtained from human umbilical vein by collagenase (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, USA) digestion as described previously [13]. The separated cells were seeded in 75 ml flasks precoated with 1% gelatin solution and grown in medium 199 (Gibco BRL Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, heparin sulphate, l-glutamine, endothelial cell growth factor (BM) (final concentration, 20 µg/ml) and 100 µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the cells were used between the 2nd and the 6th passage.

Immunofluorescence staining of HUVEC

HUVEC were prepared on 12-well Teflon-printed slides, fixed in acetone (10 min at 20°C) and incubated with blocking buffer (50% fetal calf serum in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with sera (1 : 50 in PBS) of patients with acute HSP and normal controls for 1 h. The slides were washed and FITC-conjugated antihuman immunoglobulins (Chemicon, Australia) were added to each well for a further 1 h. The specimens were then washed three times, mounted in glycerol and examined using a fluorescence microscope.

AECA detection by cell-based ELISA

HUVEC and human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC-d) (Clonetics, USA) were seeded on gelatin-coated 96-well microtitre plates (NuncTM, Denmark) at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/well. When the cellular growth became confluent 3–4 days later, cells were fixed with 0·2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and incubated with blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/0·05% azide/0·1 m Tris in ddH2O) for 60 min at 37°C to prevent non-specific binding. After washing with PBS/Tween 20 (Sigma), the serum samples, diluted in dd H2O with 1% BSA, 0·05% azide, 0·1 m Tris, and 0·05% Tween 20 at 1 : 100 for IgG/IgM detection; 1 : 50 for IgA detection, were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The sera were then removed and the plates were washed, 100 µl of peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antihuman IgG, IgA and IgM immunoglobulins were added to each well for a further 2 h at 37°C. After washing, tetramethyl benzidine (TMB) (KPL, USA) solution was added for 15 min, and stop solution (1 m hydrochloric acid) for 5 min. The optical density of each well was read at 450 nm by an ELISA reader. Initial screening of HSP patients by immunofluorescence staining and ELISA had identified a patient with high IgA binding activity to endothelial cells, and who was adopted as the positive control. A normal control sera with relative low binding activity was used as the negative control. The results were expressed as ELISA ratio (ER) = 100 × (S − A)/(B − A), where S is absorbance of sample, A is absorbance of negative control and B is positive control. Samples were recorded as positive if the ER was greater than the mean ± 3 s.d. of healthy controls.

Competitive ELISA for IgA AECA

To evaluate the role of cardiolipin in the binding repertoire of AECA, patients with both positive IgA anticardiolipin antibodies and IgA AECA were recruited into this study. IgA AECA were detected and compared among serum only and serum pretreated with cardiolipin of different concentrations (5 µg/ml, 10 µg/ml and 50 µg/ml at 37°C for 24 h).

Serum cytokine levels and pretreatment of HUVEC with cytokine

The tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) serum levels of 20 HSP patients and 10 healthy controls were detected by a commercial ELISA kit (BD PharMingen, USA). To study the effects of cytokines treatment of HUVEC on the binding of AECA, in some experiments HUVEC were treated with recombinant human TNF-α or interleukin-1 (IL-1) (Gibco BRL Life Technologies) with a concentration of 10 ng/ml for 48 h. Because of the limitations regarding blood sampling from some patients, pretreated HUVEC were used for the study of AECA in only 10 of 20 patients.

Statistical analysis

The values of AECA ELISA ratio and serum TNF-α levels in patients and controls were expressed as means ± s.e.m., and compared by Mann–Whitney U-test. The changes of AECA following HUVEC stimulation were analysed using Wilcoxon signed rank test. The correlation between serum IgA and IgA AECA was estimated by Spearman's coefficient test. Analysis of variance (anova) was used to compare the IgA AECA binding activities among serum only and serum pretreated with cardiolipin of different concentrations. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the patients

Twenty patients, aged from 2 to 14 years, had a sex distribution of 14 males and six females. For most of them (15/20) the onset of disease occurred in autumn and winter. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients. Contrary to previous studies, which revealed that glomerulonephritis developed in 20–34% of children with HSP [1], renal involvement occurred in only ywo of 20 patients in our series, and resolved completely at the convalescent stage. Under therapies with non-steroid anti-inflammation drugs or/and steroid, all patients underwent a benign and uncomplicated disease course.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

| Symptoms and signs | No. patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Purpura over lower extremities and/or buttocks | 20 (100) |

| Abdominal pain with/without SOB | 8 (40) |

| Arthritis/arthralgia | 8 (40) |

| Extremities oedema | 6 (30) |

| Scalp oedema | 2 (10) |

| Scrotum oedema | 1 (5) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 2 (10) |

| Previous URI | 14 (70) |

SOB: stool occult blood, URI: upper respiratory tract infection.

Table 2.

Laboratory data of patients at both acute and convalescent stage

| Acute stage | Convalescent stage | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (cu. mm) | 11 196·7 ± 390·5 | 6871·7 ± 670·5 | 0·027 |

| PLT (× 103/cµ. mm) | 392·7 ± 29·3 | 325 ± 26·2 | 0·028 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 253·3 ± 18·3 | 175·3 ± 29·4 | 0·046 |

| C3 (mg/dL) | 128·8 ± 14·8 | 112·9 ± 15 | 0·22 |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 33·8 ± 4·2 | 22·6 ± 3·1 | 0·043 |

Values were presented as mean ± s.e.m.

P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant; Wilcoxon signed rank test.

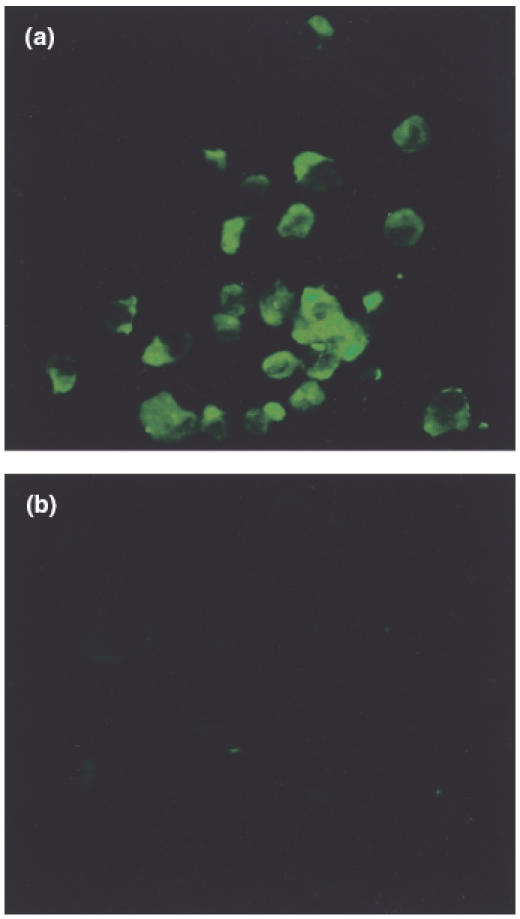

Immunofluorescence staining

The binding of serum IgA antibodies to HUVEC was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy in patients with acute HSP, but not in normal healthy controls (Fig. 1a,b).

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence staining revealed IgA immunoglobulin to endothelial cells in patients with acute onset of Henoch–Schönlein purpura (a), but not in normal healthy controls (b).

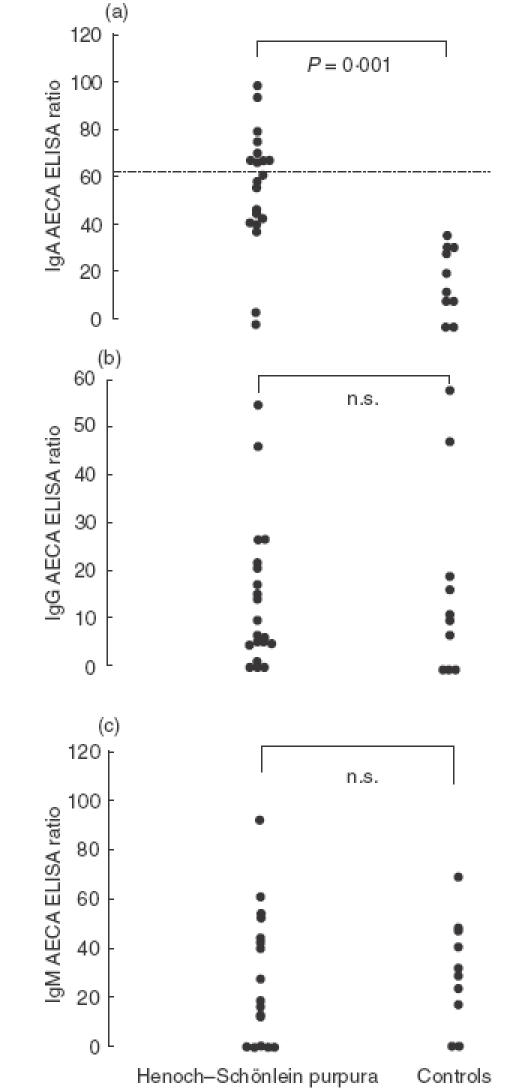

Antibodies against HUVEC without cytokine stimulation

The level of IgA AECA between HSP patients (acute stage) and healthy controls were statistically different (53·7 ± 6·1 versus 19·7 ± 4·6, P = 0·001). Nine patients (45%) revealed positive result for IgA AECA (>mean ± 3 s.d. of healthy controls, i.e. > 62·9) (Fig. 2a), and the values of IgA AECA returned to normal range during the convalescent stage (P = 0·24, compared with healthy controls). No correlation was noted between total serum IgA and IgA AECA (P = 0·2). For IgG and IgM AECA, in contrast, there was no difference between patients and controls (IgG 28·1 ± 5·8 versus 32·8 ± 7·9, P = 0·51; IgM 14·2 ± 3·3 versus 16·9 ± 6·3, P = 0·91) (Fig. 2b,c). Ten children with active JRA had no detectable serum AECA activity (IgG p = 0·96; IgA, P = 0·65; IgM, P = 0·93, compared with healthy controls, respectively).

Fig. 2.

The values of IgA (a), IgG (b), and IgM (c) antibodies against HUVEC, presented as ELISA ratio, in 20 patients with acute onset of HSP and 10 normal healthy controls. The dashed line in (a) showed the mean ± 3 s.d. of healthy controls; n.s., not significant (P > 0·05).

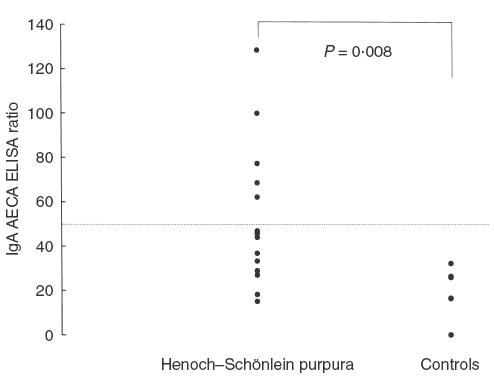

AECA against HMVEC-d

The binding activities of IgA AECA to HMVEC-d in patients with acute HSP were higher than healthy controls (52·4 ± 8·6 versus 19·6 ± 4·7, P = 0·008) (Fig. 3). Thirty-five percent of patients had positive IgA AECA (≥53·8). For IgG and IgM AECA to HMVEC-d, the levels between patients and normal controls were not statistically different (IgG, P = 0·48; IgM, P = 0·47).

Fig. 3.

The values of IgA antibodies against HMVEC-d in patients with acute HSP and normal controls. The dashed line shows the mean ± 3 s.d. of healthy controls.

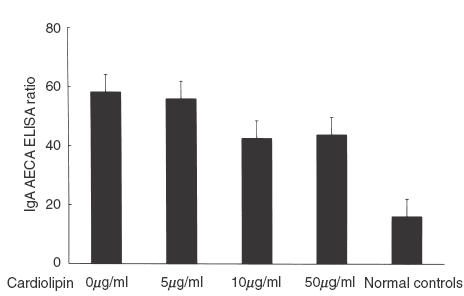

IgA AECA in serum pretreated with cardiolipin

After anticardiolipin antibodies removal, serum levels of IgA AECA were not significantly decreased (0 µg/ml 58·2 ± 14·7, 5 µg/ml 56·0 ± 14·8, 10 µg/ml 42·6 ± 13·7 and 50 µg/ml 43·8 ± 13·5, P = 0·81) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

IgA AECA levels in HSP patients (with both positive IgA anticardioplipin antibodies and IgA AECA) serum, serum pretreated with different concentrations of cardiolipin and serum of normal controls.

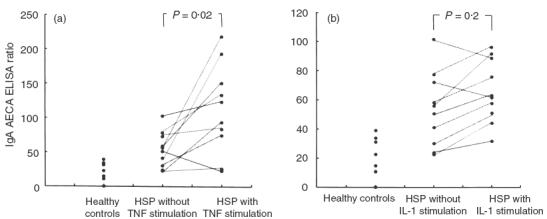

Serum cytokine levels and the effects of cytokine pretreatment

The TNF-α (pg/ml) serum levels of HSP patients elevated significantly during the acute stage (71·9 ± 10·2 versus 18·9 ± 4·8, P < 0·001), and the serum levels of IL-1 were undetectable. In order to evaluate the roles of these cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1) in the pathogenesis of this disease, 10 of 20 patients were studied for the serum levels of antibodies to cytokine-treated HUVEC. The binding activity of IgA antibodies to TNF-α pretreated HUVEC was higher than to those cells without stimulation (110·6 ± 20·3 versus 53·5 ± 8·1, P = 0·02) (Fig. 5a), and the prevalence of IgA AECA in these 10 children increased from 30% to 80% after stimulation. IL-1 treatment also tended to increase the binding activity of IgA AECA; however, it was not statistically significant (66·7 ± 6·9 versus 53·5 ± 8·1, P = 0·2) (Fig. 5b). In the control group tested for IgA AECA, no enhancement of the binding was noted after pretreatment of HUVEC with either TNF-α or IL-1 (P = 0·33, P = 0·9, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Binding activities (which were expressed as ELISA ratio) of anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECA) to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with and without TNF-α (a) or IL-1 (b) pretreatment in 10 HSP patients.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the changes of WBC counts, platelet counts and the values of complements between the acute and the convalescent stage implies the systemic inflammatory process of HSP. The clinical presentations of our previous and the present study reveal that renal involvement is not common in Chinese children with HSP [5]. Among nine patients with positive IgA AECA results in the current study, only one patient was complicated with glomerulonephritis.

Anti-endothelial cell antibodies have been found in a variety of vascular disorders including atherosclerosis, diabetic vasculopathy, vascular inflammation, graft rejection and connective tissue diseases [14–18]. In systemic vasculitis, for example, IgG and IgM AECA have been detected in the sera of patients with acute onset of Kawasaki disease, and displayed a complement-dependent cytotoxicity to HUVEC [8,19]. There was only one study [20] dealing with the relationship between AECA and HSP. In that report, antibodies of IgA isotype to bovine glomerular endothelial cells were detected in almost one-half of patients with HSP and nephritis, but were not detected in those patients without nephritis because HSP most commonly involves postcapillary venules [1], and AECA from different diseases recognize different types of endothelial cell antigens, which may be correlated with the origin of the disease [7]. We used HUVEC and HMVEC-d instead of endothelial cells from arteries or other species as targets for the detection of disease specific antibodies. HUVEC and HMVEC-d, separated directly from human umbilical vein and human skin, are categorized to macrovascular and microvascular endothelial cells, respectively. In this study IgA AECA, whether using HUVEC or to HMVEC-d, was elevated significantly in patients with acute HSP. It reveals that the auto-antigens related to this disease exist in two different endothelial cells.

In this study there was no significant correlation between serum total IgA and IgA AECA. This finding may exclude the possibility of non-specific bindings to endothelial cells due to elevated serum IgA antibodies. In addition to raised IgA serum levels, IgA contained immune complexes in vascular walls, elevated IgA anticardiolipin antibodies and activated T helper type 3 cells [5]; in our patients, during the acute stage of disease, high titres of IgA AECA provided more evidence that the pathogenesis of HSP is immune-mediated. Although the real pathogenic role of IgA AECA in HSP remains obscure, with other disease characteristics such as striking seasonal variations and preceding upper respiratory tract infections [1,2], it is proposed that HSP may be triggered by certain microorganisms that share some antigenic structures with human small vessel endothelial cells. Following the invasion of these pathogens, antigen-specific antibodies, especially of IgA form, develop and cross-react with endothelial cells. Because IgA could activate complement system via the alternative pathway and the finding of Fcα receptors on granulocytes [21,22], the endothelial cells may be further damaged by a complement-mediated or antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxic mechanism.

Our previous study revealed a high prevalence of IgA anticardiolipin antibodies in children with acute HSP [5]. To determine if the cardiolipin is the major antigen-determinant of AECA, competitive ELISA was performed. Following anticardiolipin antibodies removal, serum IgA AECA were decreased but not significantly. It is concluded that cardiolipin is one of the auto-antigens of endothelial cells in HSP, but other major antigens remain to be determined.

TNF-α is a cytokine produced by both the macrophages and T cells, and has multiple functions in the immune response. It has been well documented to play a major role in systemic inflammatory diseases such as septic shock, autoimmune diseases, tumours and systemic vasculitis [23]. In 1997, Besbas et al. [24] reported that circulating TNF-α levels of HSP patients were higher at the acute stage than at the convalescent stage. Also, immunohistochemical studies revealed marked TNF-α staining in the affected skin lesions. Our study showed similar results of increased serum levels of TNF-α in acute HSP. TNF-α induces the expression of both endothelial cell and leucocyte adhesion molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecules (VCAM), intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM) and selectins (E-selectin), which lead in turn to the migration and accumulation of leucocytes to the site of inflammation [23,25]. However, Gattorno et al. [25] found that the soluble form of these adhesion molecules were not increased in HSP patients, and concluded that the vascular damage in HSP seemed independent of TNF-α-induced adhesion molecules. In our study, IgA AECA binding activity to HUVEC pretreated with TNF-α was significantly increased. It may be supposed that TNF-α modulates the presentation of endothelial cell-specific antigen determinants, which are cryptic in the normal state, and the vascular inflammation is then mediated by the interaction of IgA AECA and endothelial cells.

IL-1 is produced by all nucleated cells, and like TNF-α has various inflammatory effects, including inducing the acute-phase response, promoting neutrophil migration and stimulating proliferation and differentiation of early haematopoietic progenitors [23]. However, serum IL-1 was undetectable in acute HSP as previous study [24], and the effect of enhancing IgA AECA binding activity to HUVEC was not statistically obvious.

In conclusion, although the results in this study do not exclude the possibility that AECA are only an epiphenomenon of vascular injury, the correlation between changes in IgA AECA titres and HSP activity and the binding enhancement by TNF-α treatment suggest an important role for IgA AECA in the disease process. Further efforts to determine the target antigens of endothelial cells by IgA AECA are in progress and would be helpful to elucidate the real role of IgA AECA in the pathogenesis of childhood HSP.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH. 90-N029)

REFERENCES

- 1.Cassidy JT, Petty RE. Textbook of pediatric rheumatology. 4. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2001. pp. 569–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 16. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. pp. 728–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knight JF. The rheumatic poison: a survey of some published investigations of the immunopathogenesis of Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Nephrol. 1990;4:533–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00869841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faille-Kuyber EH, Kater L, Kooiker CJ, Dorhout Mees EJ. IgA-deposits in cutaneous blood-vessel walls and mesangium in Henoch–Schönlein syndrome. Lancet. 1973;1:892–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang YH, Huang MT, Lin SC, Lin YT, Tsai MJ, Chiang BL. Increased TGF-α secreting T cells and IgA anticardiolipin antibodies levels during acute stage of childhood Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:285–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belizna C, Tervaert JWC. Specificity, pathogenecity, and clinical value of antiendothelial cell antibodies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1997;27:98–109. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(97)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Praprotnik S, Blank K, Meroni PL, Rozman B, Eldor A, Schoenfeld Y. Classification of anti-endothelial cell antibodies into antibodies against microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1484–94. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1484::AID-ART269>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung DYM, Collins T, Lapierre LA, Geha RS, Pober JS. Immunoglobulin M antibodies present in the acute phase Kawasaki syndrome lyse cultured vascular endothelial cells stimulated by gamma interferon. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1428–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI112454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tizard EJ, Baguley E, Hughes GRV, Dillon M. Antiendothelial cell antibodies detected by a cellular based ELISA in Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:189–92. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko K, Savage COS, Pottinger BE, Shah V, Pearson JD, Dillon M. Antiendothelial cell antibodies can be cytotoxic to endothelial cells without cytokine pre-treatment and correlate with ELISA antibody measurement in Kawasaki disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:264–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savage COS, Pottinger BE, Gaskin G, Lockwood CM, Pusey CD, Pearson JD. Vascular damage in Wegener's granulomatosis and microscopic polyarteritis: presence of anti-endothelial cell antibodies and their relation to anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;85:14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathy NK, Upadhyaya S, Sinha N, Nityanand S. Complement and cell mediated cytotoxicity by antiendothelial cell antibodies in Takayasu's arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:805–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick RC. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2745–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George J, Meroni PL, Gilburd B, Raschi E, Harats D, Shoenfeld Y. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies in patients with coronary atherosclerosis. Immunol Lett. 2000;73:23–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wangel AG, Kontianen S, Scenini T, Schlenzka A, Wangel D, Maenpaa J. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;88:410–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tixier D, Tuso P, Czer L, et al. Characterization of antiendothelial cell and antiheart antibodies following heart transplantation. Transpl Proc. 1993;25:931–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan TM, Frampton G, Jayne DR, Perry GJ, Lockwood CM, Cameron JS. Clinical significance of anti-endothelial cell antibodies in systemic vasculitis: a longitudinal study comparing anti-endothelial cell antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:387–92. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum J, Pottinger BE, Woo P, et al. Measurement and characterization of circulating anti-endothelial cell IgG in connective tissue diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;72:450–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujieda M, Oishi N, Kurashige T. Antibodies to endothelial cells in Kawasaki disease lyse endothelial cells without cytokine pretreatment. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:120–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujieda M, Oishi N, Naruse K, et al. Soluble thrombomodulin and antibodies to bovine glomerular endothelial cells in patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:240–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wines BD, Sardjono CT, Trist HH, Lay CS, Hogarth PM. The interaction of Fc alpha RI with IgA and its implications for ligand binding by immunoreceptors of the leukocyte receptor cluster. J Immunol. 2001;163:1781–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Oldroyd RG, Lachmann PJ. Neutrophil lactoferrin release induced by IgA immune complexes differed from that induced by cross-linking of fcalpha receptors (FcalphaR) with a monoclonal antibody, MIP8a. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:106–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parslow TG, Stites DP, Terr AI, Imboden JB. Medical immunology. 10. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2001. pp. 148–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besbas N, Saatci U, Ruacan S, Ozen S, Sungur A, Bakkaloglu A, Elnahas AM. The role of cytokines in Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:456–60. doi: 10.3109/03009749709065719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gattorno M, Vignola S, Barbano G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor induced adhesion molecule serum concentrations in Henoch–Schönlein purpura and pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]