Abstract

Hereditary periodic fever syndromes comprise a group of distinct disease entities linked by the defining feature of recurrent febrile episodes. Hyper IgD with periodic fever syndrome (HIDS) is caused by mutations in the mevalonate kinase (MVK) gene. The mechanisms by which defects in the MVK gene cause febrile episodes are unclear and there is no uniformly effective treatment. Mutations of the TNFRSF1A gene may also cause periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS). Treatment with the TNFR-Fc fusion protein, etanercept, is effective in some patients with TRAPS, but its clinical usefulness in HIDS has not been reported. We describe a 3-year-old boy in whom genetic screening revealed a rare combination of two MVK mutations producing clinical HIDS as well as a TNFRSF1A P46L variant present in about 1% of the population. In vitro functional assays demonstrated reduced receptor shedding in proband's monocytes. The proband therefore appears to have a novel clinical entity combining Hyper IgD syndrome with defective TNFRSF1A homeostasis, which is partially responsive to etanercept.

Keywords: etanercept, HIDS, mevalonate kinase, TNFRSF1A, TRAPS

Introduction

The hereditary periodic fevers are rare disorders characterized by intermittent self-limited inflammatory episodes with recurrent fever, synovial/serosal inflammation leading to arthritis and abdominal pain, rashes, uveitis/conjunctivitis and, in some subjects, AA amyloidosis. Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), which is the most common of all these diseases, is an autosomal recessive condition caused by mutations in the MEFV gene on chromosome 16 [1,2]. Hyper IgD with periodic fever syndrome (HIDS) is also recessively inherited, and is caused by mutations in the mevalonate kinase (MVK) gene resulting in deficient activity of the mevalonate kinase enzyme [3,4]. The mechanisms by which abnormalities in MVK activity causes febrile episodes are unclear. The most common dominantly inherited condition is familial Hibernian fever (FHF), which has been renamed as TNF-receptor–associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) with the recognition that mutations of the TNFRSF1A gene (formerly TNFR1) are responsible for the molecular defect [5,6].

Different treatment strategies are recommended for each of these conditions. FMF responds well to colchicine, possibly through inhibition of microtubule polymerization [7], whereas TRAPS often responds poorly to colchicine but rapidly to steroids [8]. More recently soluble TNFR2-Fc fusion protein, etanercept (EnbrelTM), has shown some promise in the treatment of TRAPS [8,9]. HIDS is unresponsive to steroids and is generally only partially responsive to NSAIDs. We report the rare occurrence (perhaps as infrequent as one in 5 million) of Hyper IgD syndrome in a patient with the P46L variant of the TNFRFS1A gene as well as the presence of in vitro functional abnormalities in TNFRFS1A shedding from peripheral blood monocytes. The clinical responsiveness of the febrile episodes to TNF receptor blockade (etanercept) is also described.

Patients and methods

Patients and controls

The proband attended the regional paediatric immunology clinic at Royal Manchester Children's Hospital in Manchester, United Kingdom. Details of his family's clinical history have been gathered from clinical records and at consultation. A total of 15 additional cases of HIDS with defined MVK gene mutations were screened for P46L, R92Q and R92P mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene. Four healthy laboratory volunteers were used as controls for monocyte TNFRSF1A shedding experiments.

Assays for urinary mevalonic acid levels and leucocyte mevalonate kinase activity

Mevalonic acid was measured in urine by stable isotope dilution gas chromatography mass spectroscopy of the trimethylsilylether/esters using [2H7] mevalononolacton as an internal standard [10]. MK activity was determined in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (MNC) using 14C-labelled mevalonate as the substrate [11].

Mevalonate kinase gene mutation screen

Mutation analysis was performed on genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes as described previously [12].

Measurement of soluble TNF receptors

The levels of sTNFRSF1A (p55) and sTNFRSF1B (p75) were measured in plasma or culture supernatants by solid-phase ELISA, using the Quantikine soluble TNFR1 immunoassay kit (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). The assays measured total amount of receptor present, i.e. free receptor plus receptor bound to TNF. For both tests, intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were < 7·5%. Reference intervals were 0·4–1·7 ng/ml and 2–5·5 ng/ml for sTNFRSF1A and sTNFRSF1B, respectively.

TNFRSF1A expression and shedding

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from freshly collected peripheral blood using Ficoll gradient separation (Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway). Mononuclear cells were isolated from the proband, his sister and his father as well as a group of four unaffected controls. Parallel cultures, each containing 106 cells/ml, were maintained for 30 min in a 37°C/5%CO2 incubator in the presence or absence of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 10 ng/ml, Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MO, USA). Each sample was then collected and incubated in triplicate with FITC labelled TNF-R1 MoAb (TNFR1FITC) (R&D Systems) for 45 min at 4°C in the dark. An isotype MoAb, γ1FITC from Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry System (BDIS, San Jose, CA, USA) and an unlabelled sample were included as controls. Double labelling was also carried out by simultaneous incubation with PE labelled CD14 recognizing the monocyte subset (BD). The cells falling within the CD14+ monocyte region were acquired onto a FACSort flow cytometer (BDIS) and analysed using lysis software. The level of TNFRSF1A expression on monocytes was evaluated by setting a marker beyond the negative peak of the isotype control.

TNFRSF1A mutation screen

Genomic DNAs from all available family members were sequenced for exons 2, 3, 4 and 5 of TNFRSF1A, encoding the extracellular domain, as described previously [5]. A restriction fragment polymorphism (RFLP) assay was developed for the P46L variant to look for its presence in 96 Caucasian controls as well as the remaining family members. As the P46L variant abolishes a restriction site for HpaII enzyme a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product of 575 bp was amplified with TNFRSF1A primers for exons 2–3, and digested with HpaII. A combined version of the assay and an RFLP assay for the R92P and R92Q low-penetrance mutations was used to screen 15 additional HIDS patients. The following primers were used: forward (5′-ACC AAG TGC CAC AAA GGA AC-3′) and reverse (5′-CCT GCA GCC ACA CAC GGT GCC C-3′). The ‘C’ nucleotide at position 365 in the reverse primer is substituted for a ‘T’ nucleotide so as to create a SmaI restriction site when the R92P mutation is present [13]. The obtained fragments were digested with SmaI and HpaII (MspI). A SmaI recognition site (CCC GGG) is digested always by HpaII (CCGG). Thus the WT allele is cut once by SmaI and twice by HpaII. The P46L abolishes a SmaI and a HpaII restriction site. The R92Q mutation abolishes a HpaII site and the R92P mutation introduces a second SmaI site.

MEVF mutation screen

Exon 10, where the most frequently occurring mutations (M680I, M694V, M694I, V726A) are found, was sequenced in the proband, as described previously [14].

Results

Clinical features of periodic fever syndrome

The index case was a 3-year-old boy who suffered from high fevers from 3 days of age, with recurrences at every 3–5 weeks thereafter. Despite extensive investigations no infective cause was found. A typical attack was preceded by anorexia and a musty body odour, followed by coryzal symptoms, conjunctival congestion, cervical lymphadenopathy, severe abdominal pain and diarrhoea, with a high fever lasting 5–7 days. The fever was often associated with recurrent, prolonged febrile seizures. Routine vaccinations and upper respiratory tract infections precipitated the febrile episodes. The child's Caucasian mother, Afro-Caribbean father and 10-year-old sister were all healthy and had no clinical history to suggest periodic fever syndrome (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of family showing the segregation of both the TNFRSF1A variant and MVK mutations. The normal gene sequences are represented as WT (wild-type). The proband (II-1), who has the P46L TNFRSF1A variant, is a compound heterozygote for MVK mutations (V377I and G211A) is the only symptomatic family member (shaded box).

Laboratory investigations confirming diagnosis of hereditary periodic fever syndrome (Table 1)

Table 1.

Specific investigations for periodic fever syndromes

| Proband | Sister | Mother | Father | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIDS investigations | ||||

| IgD (0·015–0·040 g/l) | 1·6 | 0·049 | ||

| Cholesterol (2·5–6·5 mmoles/l) | 4·1 | 6·9 | ||

| Urinary mevalonic acid (<1 mmol/mol creatinine) (when symptomatic) | 14·4 | normal | ||

| Leukocyte mevalonate kinase activity 103 ± 33 pmol/min.mg) | 0·82–1·3 | 106 | not done | 69 |

| Mevalonate kinase gene mutation | 1129 G > A (V377I) and 632 G > C (G211A) | nil | 1129 G > A (V377I) | 632 G > C (G211A) |

| TRAPS investigations | ||||

| TNFRSF1A gene mutation | 224 C > T (P46L) | 224 C > T (P46L) | nil | 224 C > T (P46L) |

| sTNFRSF1A (746–1966 pg/ml) | 589 | 715 | 818 | 343 |

| sTNFRSF1B (1003–3170 pg/ml) | 1768 | 1989 | 1917 | 950 |

| TNFRSF1A shedding post-PMA | <15% | 35% | not done | 30% |

| Amyloid screen | ||||

| SAA level (<3·0 mg/l) (when symptomatic) | 384 | |||

| (when asymptomatic) | 1·8 | 1·8 | ||

| proteinuria (g/l) | <0·1 | <0·1 | <0·1 | |

High serum IgD suggested the diagnosis of HIDS in the proband and further investigations revealed an elevated urinary excretion of mevalonic acid during an attack, with reduced leucocyte mevalonate kinase activity. Two mutations in the MVK gene were found, consisting of the common V3771 (1129 G > A) mutation and a novel G > C transversion at nucleotide 632 (G211A)(Fig. 1). The proband's sister had normal MK activity and MVK mutation analysis. The parents were heterozygous asymptomatic carriers of the MVK mutations. The child's mother had the V3771 mutation and the father possessed the G211A change.

Mutational analysis of the TNFRSF1A gene revealed a P46L (224 C > T) variant in the proband, his sister and father, but not in the mother. The P46L change and two other low-penetrance mutations, which have also been described in the TNFRSF1A gene, R92Q (362 G > A) and R92P (362 G > C) [15,16], were tested in a panel of 15 confirmed HIDS patients by a PCR-RFLP method. No additional TNFRSF1A mutations were detected in this cohort, suggesting that TNFRSF1A mutations are not common in patients with HIDS.

Because of the prominent episodes of severe abdominal pain in the proband, FMF was also excluded by directly sequencing exon 10 of the MEFV gene where the majority of mutations are found. No mutations were present.

Additional investigations examining in vitro functional abnormalities in TNFRSF1A shedding

Serum TNFRSF1A levels were low in the proband, sister and father but not the mother (Table 1). Flow cytometry was used to study cell surface expression of TNFRSF1A after PMA activation on monocytes in the proband, his father and sister. PMA activation induced at least 35% TNFRSF1A shedding compared with basal levels in the monocyte subpopulation of four control subjects, confirming previous findings [5]. Less than 30% TNFRSF1A shedding was therefore considered to indicate impairment of the shedding mechanism. Post-PMA stimulation TNFRSF1A shedding in the proband was <15%, well below normal control values. Conversely, the sister's monocytes showed a normal level of shedding (35%) and the father's mononuclear cells showed a level of TNFSRF1A shedding in the lower normal range (30%). In all cases the triplicate readings were reproducible (less than 5% variation).

Clinical response to treatment

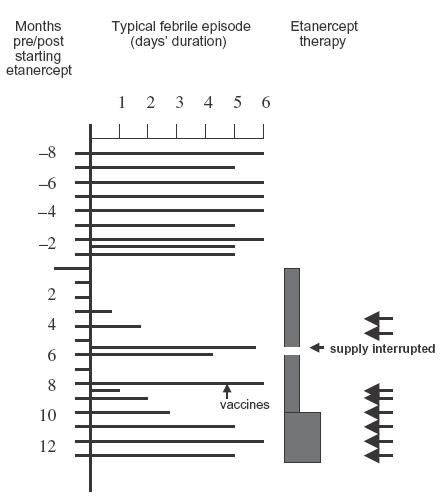

The patient showed no response to a 6-month trial of anti-inflammatory doses of aspirin (blood level 150–300 mg/l) or to a 2-month trial of intermittent high dose oral prednisolone (2 mg/kg), given during the prodrome to a febrile episode. Because of the genetic and laboratory evidence suggesting possible abnormalities in the TNF receptor pathway, 0·4–0·8 mg/kg etanercept (EnbrelTM, Wyeth, Maidenhead, UK) given subcutaneously twice a week over a 12-month period was tried (Fig. 2). There was complete abrogation of the patient's symptoms for the first 3 months of treatment. However, over the following 6 months three febrile episodes occurring while the patient was on this regime were aborted within 24 h by additional larger doses of etanercept (0·8 mg/kg) given subcutaneously during the initial 48 h. Two febrile episodes of normal duration occurred when the etanercept supply was unfortunately interrupted because of the Christmas/New Year holiday. As the proband had responded well to etanercept treatment, the third dose of DT, OPV and Hib were administered 8 months into his trial of etanercept, as in infancy the child had received only the first two sets of vaccinations. Unfortunately, this large antigen dose led to a febrile episode which was unresponsive to etanercept. Nine months after starting the etanercept treatment, the proband started to develop more frequent febrile episodes, which were less responsive to etanercept, and at 12 months etanercept was stopped, with a view to giving the patients a period off etanercept, to determine whether this would lead to a further period of responsiveness when the drug was reintroduced.

Fig. 2.

Clinical response of proband to etanercept therapy over a 12-month period. Filled boxes at the right of the figure indicate continuous treatment with etanercept at 0·4 and then 0·8 mg/kg/dose twice weekly. Arrows indicate extra etanercept boluses (0·8 mg/kg/dose).

Discussion

This study demonstrates evidence of a rare combination of Hyper IgD syndrome in association with defective TNFRSF1A shedding in peripheral blood monocytes. The diagnosis of HIDS was suggested clinically by the early age of onset and further supported by a grossly elevated serum IgD level. The finding of two mevalonate kinase gene mutations combined with depressed leucocyte mevalonate kinase activity confirmed a diagnosis of HIDS.

Previous studies have found that the P46L variant of the TNFRSF1A gene can be considered as a low penetrance mutation, because it has been associated with a milder and more variable clinical phenotype when compared with other TNFRSF1A gene mutations, and it is not always associated with disease, being present in ∼1% of control chromosomes in some studies [13,15,16]. P46L was not found in a panel of 96 healthy European controls but has been reported in 1/69 Arab controls [15]. Furthermore, in a different series P46L was detected in one of 170 northern-European controls and in three of 156 African American controls, at a combined gene frequency of 1%[13]. In this study, the fact that the proband's sister and father carried the same TNFRSF1A gene mutation and were asymptomatic is in keeping with the P46L mutation being a silent natural polymorphism. However, the fact that the mutation in the proband was associated with decreased serum TNFRSF1A levels as well as increased basal expression levels on monocytes, with reduced shedding of the receptor on direct in vitro testing when compared with controls, is consistent with this mutation having functional relevance. It is possible that dysfunction of intracellular TNF signalling, and altered transcription factor activation, e.g. NF-κB may result from increased basal expression levels but this remains to be proven [17].

The in vitro abnormalities in TNF receptor shedding in this patient prompted us to examine the possible clinical usefulness of TNF receptor blockade, especially as the patient was unresponsive to conventional therapies with NSAIDS and prednisolone. The abrogation of the febrile episode by etanercept suggested that abnormal physiological effects of TNF were contributing to the clinical phenotype. HIDS has been associated previously with raised TNF and sTNFR levels [16] and in vitro IgD can stimulate TNF release [18]. It is also possible that the presence of HIDS may have contributed to the functional abnormalities in TNFRSF1A and contributed to the febrile episodes by prolonging TNF stimulation of target cells [19].

This is the first study to demonstrate partial clinical effectiveness of TNF receptor blockade with etanercept in HIDS. Unfortunately, tachyphylaxis to the drug developed after 9 months, initially with reduced and subsequently with complete lack of responsiveness by 10 months. In this patient, a ‘drug holiday’ is currently being tried to determine whether this will result in further periods of relief from febrile episodes. Additional studies are required to determine the role and the optimal regime of this drug in HIDS and a better understanding of the possible link between abnormal TNF homeostasis and Hyper IgD syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to L. Dorland for performing urinary mevalonic acid analysis, G. J. Romeijn for performing mevalonate kinase enzyme assays and J. Koster for performing MVK mutation analysis. P. Hawkins from the National Amyloidosis Centre, London, UK performed serum amyloid A analysis. Funding of etanercept treatment was obtained from the Paediatric Directorate at Royal Preston Hospital NHS Trust, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.International FMF. Consortium ancient missense mutations in a new member of the RoRet gene family are likely to cause familial Mediterranean fever. Cell. 1997;9:797–807. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The French FMF Consortium. A candidate gene for familial Mediterranean fever. Nat Genet. 1997;17:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houten SM, Kuis W, Duran M, et al. Mutations in MVK, encoding mevalonate kinase, cause hyperimmunoglobulinemia D and periodic fever syndrome. Nat Genet. 1999;22:175–7. doi: 10.1038/9691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drenth JP, Cuisset L, Grateau G, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding mevalonate kinase cause hyper-IgD and periodic fever syndrome. Nat Genet. 1999;22:178–81. doi: 10.1038/9696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, et al. Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell. 1999;97:133–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aksentijevich I, Galon J, Soares M, et al. The tumor-necrosis-factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: new mutations in TNFRSF1A, ancestral origins, genotype–phenotype studies, and evidence for further genetic heterogeneity of periodic fevers. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:301–4. doi: 10.1086/321976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skoufias D, Wilson L. Mechanism of inhibition of microtubule polymerization by colchicine: inhibitory potencies of unliganded colchicine and tubulin–colchicine complexes. Biochemistry. 1992;31:738–46. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galon J, Aksentijevich I, McDermott MF, O'Shea JJ, Kastner DL. TNFRSF1A mutations and autoinflammatory syndromes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:479–86. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drewe E, McDermott EM, Powell RJ. Treatment of the nephritic syndrome with etanercept in patients with the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;243:1044–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindenthal B, Simatupang A, Dotti MT, Federico A, Lutjohann D, von Bergmann K. Urinary excretion of mevalonic acid as an indicator of cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:2193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann GF, Brendel SU, Scharfschwerdt SR, Shin YS, Speidel IM, Gibson KM. Mevalonate kinase assay using DEAE-cellulose column chromatography for first-trimester prenatal diagnosis and complementation analysis in mevalonic aciduria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15:738–46. doi: 10.1007/BF01800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houten SM, Koster J, Romeijn G, et al. Organization of the mevalonate kinase (MVK) gene and identification of novel mutations causing mevalonate aciduria and hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D and periodic fever. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:253–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aksentijevich I, Galon J, Soares M, et al. The tumor-necrosis-factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: new mutations in TNFSF1A, ancestral origins, genotype-phenotype studies, and evidence for further genetic heterogeneity of periodic fevers. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:301–410. doi: 10.1086/321976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booth DR, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, et al. The genetic basis of autosomal dominant familial Mediterranean fever. Q J Med. 2000;93:217–22. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.4.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aganna E, Zeharia A, Hitman GA, et al. An Israeli Arab patient with a de novo TNFRSF1A mutation causing tumor necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) Arth Rheum. 2002;469:245–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200201)46:1<245::AID-ART10038>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aganna E, Aksentijevich I, Hitman GA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS) in a Dutch family: evidence for a TNFRSF1A mutation with reduced penetrance. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:63–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDermott MF. TNF and TNFR biology in health and disease. Cell Mol Biol. 2001;47:619–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drenth JP, van Deuren M, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, Schalkwijk CG, van der Meer JW. Cytokine activation during attacks of the hyperimmunoglobulinemia D and periodic fever syndrome. Blood. 1995;85:3586–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drenth JP, Goertz J, Daha MR, van der Meer JW. Immunoglobulin D enhances the release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-1 beta as well as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist from human mononuclear cells. Immunology. 1996;88:355–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]