Abstract

The disparity between the number of available renal donors and the number of patients on the transplant waiting list has prompted the use of expanded-criteria-donor (ECD) renal allografts to expand the donor pool. ECD allografts have shown good results in appropriately selected recipients, yet a number of renal allografts are still discarded. The use of dual renal transplantation may lower the discard rate. Additionally, the use of perfusion systems may improve acute tubular necrosis rates with these allografts. We report a successful case of a dual transplant with ECD allografts using a perfusion system. The biopsy appearance and the pump characteristics were suboptimal for these kidneys, making them unsuitable for single transplantation; however, the pair of transplanted kidneys provided increased nephron mass and functioned well. We recommend that ECD kidneys that are individually nontransplantable be evaluated for potential dual renal transplantation. Biopsy criteria and perfusion data guidelines must be developed to improve the success rates with ECD dual renal allografts. Finally, recipient selection is of utmost importance.

The shortage of available organs for potential renal transplant recipients is an escalating problem. Expanded criteria donors (ECDs) have been clearly defined and have increased the donor pool. Another modality to expand the donor pool is the use of two renal allografts (that individually would be discarded) in a single recipient.

The concept of using two allografts is not new to renal transplantation. In fact, there is a large experience using en bloc renal allografts from pediatric donors. Of course, the donor allografts must be chosen according to a very specific protocol and matched to the recipient by size. Recently, discardable kidneys from adult cadaveric donors have also been used in dual renal transplants to expand the donor pool. As with the pediatric cases, donor selection is crucial in obtaining good results. Previous studies have demonstrated this point, and registries have been established.

Currently, the ECD renal allograft is assessed mainly by the histologic appearance of the renal biopsy (glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, fibrosis, and vasculopathy) and the clinical data provided on the donor (urine output and calculated creatinine clearance) (1). Recently, continuous perfusion systems and the data they provide have given the transplant surgeon more information on the usability of the potential renal allograft. This case presentation demonstrates the use of renal biopsy data as well as perfusion system data in determining the transplantability of the donor renal allografts.

CASE PRESENTATION

Donor

Renal allografts were harvested from a 64-year-old donor with a history of hypertension and diabetes. The donor had been seen recently by his primary care physician and was taking nicardipine, dopamine, propofol, dexamethasone, labetalol, mannitol, vancomycin, and piperacillin/tazobactam. During the course of the workup, during which the donor was receiving only dopamine (average rate, 7.5 mcg/kg per minute), his average systolic blood pressure was 130 mm Hg, and his average urine output, 145 mL/h. His liver and kidneys were recovered uneventfully using University of Wisconsin solution.

The donor's initial serum creatinine level was 1.0 mg/dL; his terminal creatinine level was 1.3 mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen level, 24 mg/dL. Urinalysis demonstrated no protein, trace glucose, 1+ blood, 10 to 15 red blood cells, 0 to 1 white blood cells, pH 7.0, and a specific gravity of 1.010. The calculated glomerular filtration rate was 89 mL/min ([140 – age] × [weight]/[serum creatinine × 72]).

In the left kidney, 155 glomeruli were seen; 19% were sclerosed, and mild arteriosclerosis and mild patchy interstitial fibrosis were found. In the right kidney, 135 glomeruli were seen, with 14% sclerosed; there was moderate arteriosclerosis and two foci of scarring with moderate to severe interstitial fibrosis. Minimal acute tubular necrosis was seen in both kidneys.

The right kidney was 14 cm long and 7 cm wide and had two arteries on a common aortic cuff. The vein was reconstructed in the standard fashion using a vena caval extension. The left kidney was 13 × 7 cm and had a single artery and single vein. The arteries contained minimal plaque, and the aortic patch had mild atherosclerosis.

The cold ischemia time (CIT) totaled 14 hours, the last 6 hours of which were on continuous perfusion pumps. The pump used was the LifePort Kidney Transporter, model LKT-100 (Organ Recovery Systems, Des Plaines, IL). The pump data showed resistance of <0.4 mm Hg/mL per minute and flows of >70 mL/min for both kidneys. The temperature was maintained between 4°C and 6°C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kidney pump data

| Time on pump (min) | Pressure (mm Hg) | Flow(mL/min) | Resistance (mm Hg/mL per min) | Ice temperature (°C) | Infusion temperature (°C) |

| Right kidney | |||||

| 0 | 33 | 14 | 1.99 | 3.3 | 9.8 |

| 30 | 27 | 29 | 1.22 | 3.2 | 7.4 |

| 60 | 34 | 49 | 0.60 | 3.0 | 7.3 |

| 90 | 34 | 60 | 0.51 | 2.6 | 7.0 |

| 150 | 34 | 70 | 0.40 | 2.8 | 6.1 |

| 240 | 34 | 74 | 0.35 | 2.4 | 5.2 |

| 305 | 35 | 72 | 0.32 | 2.6 | 5.2 |

| Left kidney | |||||

| 0 | 29 | 16 | 1.63 | 1.5 | 8.6 |

| 30 | 34 | 15 | 1.99 | 1.5 | 7.7 |

| 60 | 34 | 29 | 1.10 | 1.3 | 6.2 |

| 90 | 34 | 36 | 0.82 | 1.2 | 6.0 |

| 150 | 34 | 50 | 0.59 | 1.3 | 5.5 |

| 240 | 34 | 68 | 0.42 | 1.3 | 4.5 |

| 305 | 34 | 80 | 0.33 | 1.3 | 4.3 |

Recipient and clinical course

The recipient was a 66-year-old woman with a blood type of A Rh-positive and a history of end-stage renal disease. She had been on hemodialysis for 2 years prior to transplantation. In addition, she had undergone mitral valve replacement for rheumatic heart disease and atrial flutter, both necessitating use of warfarin, and had a history of hypertension, colon resection for polyps, hysterectomy, and incisional hernia repair. Her medications included metoprolol, omeprazole, diltiazem, and warfarin. The patient's panel reactive antibody result was 0%, and cytotoxic cross-match was negative. The human leukocyte antigen match was at the A2 locus only.

Two kidneys were transplanted without any complication. The left renal allograft was implanted retroperitoneally in the right iliac fossa, and the right renal allograft was implanted in the left iliac fossa. The renal arteries were implanted on the external iliac arteries in an end-to-side fashion. The renal veins were implanted on the external iliac veins, also in an end-to-side fashion. The ureters were implanted on the recipient bladder using the modified Liche technique for neoureterocystostomy with two implantation sites. The kidneys made a scant amount of urine intraoperatively.

Postoperative immunosuppression included the use of rabbit antithymocyte globulin (1.5 mg/kg) given intraoperatively and continued postoperatively. Additionally, tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, was introduced on posttransplant day 7 (Table 2). Mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone were also used as induction medications.

Table 2.

The patient's immunosuppressive regimen and laboratory results

| Posttransplant day | ||||||||||||

| Immunosuppressant characteristics | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Drugs used | ||||||||||||

| RATG (mg/kg) | 1.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | ||||||

| Tacrolimus (mg) | 1 | 1 BID | 1 BID | 1 BID | 1 BID | |||||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil (mg) | 1000 | 1000 BID | 1000 BID | 1000 BID | 1000 BID | 1000 BID | 1000 BID | 1000 BID | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Prednisone | 50 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||||||||

| Tacrolimus level (ng/mL) | 5.4 | 9 | 10.3 | |||||||||

| Urine output (mL/24 h) | 2070 | 2043 | 1700 | 2325 | 1050 | |||||||

| Serum BUN (mg/dL) | 18 | 28 | 36 | 44 | 60 | 43 | 57 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 8.9 |

RATG indicates rabbit antithymocyte globulin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; BID, twice a day.

After transplant, the patient developed atrial flutter, and an amiodarone drip was initiated. Carbon dioxide retention with resultant narcosis required intubation and mechanical ventilation assistance for the first 24 hours after surgery. After extubation, the patient's mental status slowly improved. Her altered mental status was attributed to her extreme sensitivity to narcotics. At the time of discharge, the patient was neurologically intact.

Cardiac management included maintenance on an amiodarone drip for the initial portion of the patient's intensive care unit stay. Ultimately, oral amiodarone and metoprolol were used. For anticoagulation, heparin 5000 units was given subcutaneously every 12 hours; eventually warfarin was resumed.

The patient developed a gastrointestinal bleed, which was attributed to thrombocytopenia. Hemodynamically, she was quite stable, and no intervention was needed.

The renal allografts initially went through a phase of oliguric acute tubular necrosis with small urine flow. On posttransplant day 1, a Doppler ultrasound of the renal transplants demonstrated a resistive index of the left renal artery of 1.0 and of the right renal artery of 0.79 to 1.0. No hydronephrosis or venous thrombosis was present. On posttransplant day 5, Doppler ultrasound was ordered due to persistent increases in the serum creatinine level. The resistive indexes were 1.0 in both the left and right renal allografts. On posttransplant day 10, a third ultrasound was obtained to rule out perinephric hematoma after the patient's hematocrit dropped.

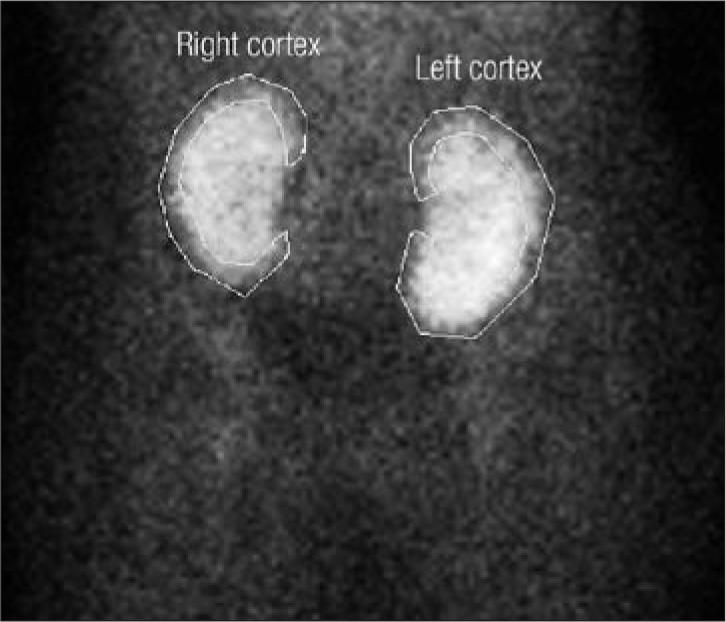

On posttransplant day 2, the patient's urine output increased to 410 mL/24 h. A renogram using technetium 99 was obtained, demonstrating findings consistent with acute tubular necrosis (Figure 1). Over the next few posttransplant days, urine output increased steadily; however, the patient required hemodialysis on posttransplant day 4 for progressive volume overload. After a single course of hemodialysis, the patient's creatinine level gradually dropped. Improvement in the renal function allowed the delayed introduction of tacrolimus.

Figure 1.

Renogram of dual renal allografts on posttransplant day 2, consistent with acute tubular necrosis.

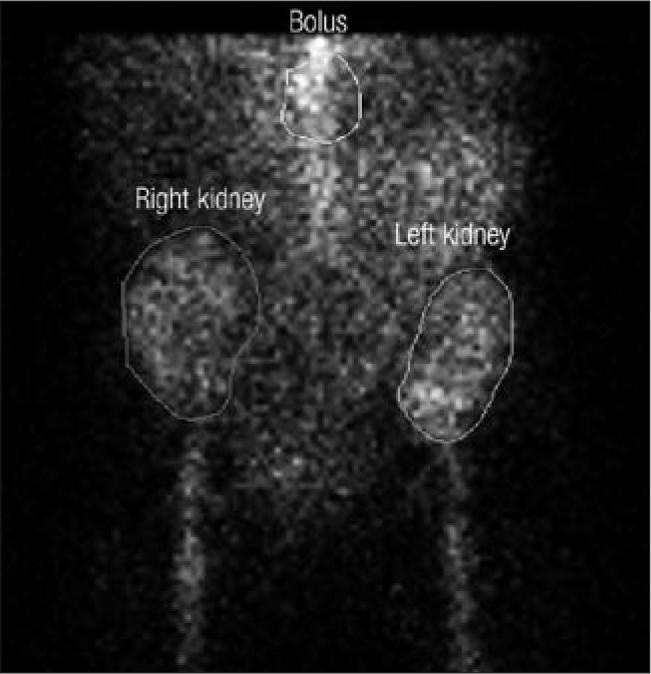

The patient was discharged on posttransplant day 11 with functioning renal allografts. The serum creatinine level demonstrated a downward trend with brisk urine output, and no hemodialysis was necessary after posttransplant day 4. At 3 months (Figure 2), the serum creatinine level was 1.0 mg/dL, the renal scan showed acceptable function, and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group equation) was 59 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Figure 2.

Renogram demonstrating normal function at 3 months posttransplant.

DISCUSSION

Several strategies are available to expand the donor pool for renal transplantation. ECD allografts, pediatric en bloc kidneys, living-donor kidney transplants, paired donor exchange, and dual kidney transplants (as presented here) have all been demonstrated to be successful. The most important factor for success is selecting an appropriate donor and pairing the allograft with the optimal recipient; if that is not done, the patient's chance of having a subsequent successful transplant may be ruined because of sensitization to human leukocyte antigens from the failed kidney transplant.

Dual kidney transplantation is hypothesized to work based on its increased nephron mass. Renal allografts may lose a variable amount of nephron mass from ischemia and reperfusion injury. As is well known, renal allografts from younger donors tolerate more loss and recover better than renal allografts from older donors. Yet, dual renal allografts from donors ≥54 years have been shown in the dual kidney registry to have outcomes as good as those of allografts from younger donors (2).

Additionally, comorbid donor diseases such as diabetes and hypertension generally impact the recovery times of renal allografts as well as long-term graft survival. Interestingly, in addition to being older, dual kidney donors have been shown to have poorer creatinine clearance, more comorbid diseases, and lower posttransplant urine outputs. However, recipients of dual kidney allografts have survival rates, allograft function, and outcomes comparable to those of recipients of single renal transplants (3). The experience at Stanford has indicated that best results are obtained with ECD allografts from donors >59 years with an adjusted creatinine clearance <90 mL/min as dual renal transplants in age- and size-matched recipients (4), keeping the CIT <24 hours (5).

Long-term follow-up analysis of dual renal transplants demonstrates the impact of delayed graft function (DGF) and CIT. The occurrence of DGF is dependent on CIT; therefore, the presence of the two will impact the 1-year graft survival rate (90% for prompt graft function vs 74% for DGF) and 5-year graft survival rate (79% for prompt graft function vs 54% for DGF). The 5-year graft survival rates for dual renal transplants were reported to be excellent (6). Eight-year actuarial results from Stanford confirmed equivalence in ECD older-aged dual renal transplants when compared with single renal transplants from younger donors (7), further showing the ability of dual renal transplants to expand the donor pool, especially for older individuals on the transplant list who may not be able to tolerate a lengthy wait.

Renal allografts from donors who had hypertension or diabetes usually demonstrate the end vascular effects of the disease process (especially in advanced-donor-age allografts). The presence of vasculopathy within the allografts is known to affect the longevity of allograft survival due to reduction of perfusion at the time of recovery and reperfusion, leading to a significant amount of acute tubular necrosis, from which the renal allograft will not be able to recover. This necrosis ultimately leads to graft nonfunction, subsequent graft loss, and the patient's return to hemodialysis.

Machine perfusion of renal allografts has been used since the early 1970s (8). Since then, the question of perfusion pump vs cold storage has been debated from time to time. The development of Euro-Collins solution and subsequently University of Wisconsin solution and their associated lengthened cold storage times seemed to make perfusion pumps unnecessary (9).

The use of renal allograft pumps has now resurfaced, especially with the increase in ECD kidney allografts. Despite having a greater number of risk factors for reduced graft viability, the pumped ECD kidneys had graft survival similar to that of simple cold storage kidneys. Matsuoka et al indicated that the use of renal perfusion pumps has decreased the incidence of DGF, which translates to lower overall costs and increased utilization of donor kidneys (10). Schold et al confirmed the pumps' effect on DGF and stated that discard rates were decreased when perfusion systems were utilized (11). Though not discussed above as a way to expand the donor pool, the non–heart-beating donor renal allografts may also benefit by using the machine perfusion systems (12); however, this theory is yet to be confirmed.

The presentation of this case culminates in a clear next step for maximizing the donor pool. Dual kidney recipients have good if not excellent outcomes, but there is always room for improvement. The lessons learned from dual kidney donor selection and the data obtained from the pump systems may now allow us to identify more usable paired (dual) kidneys. The selection criteria need to be defined through clinical trials to optimize successful dual renal transplantation.

References

- 1.Karpinski J, Lajoie G, Cattran D, Fenton S, Zaltzman J, Cardella C, Cole E. Outcome of kidney transplantation from high-risk donors is determined by both structure and function. Transplantation. 1999;67(8):1162–1167. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199904270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nghiem DD. Low absolute glomerular filtration rates in the living kidney donor: a risk factor for graft loss. Transplantation. 2001;72(8):1465–1466. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200110270-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CM, Carter JT, Weinstein RJ, Pease HM, Scandling JD, Pavalakis M, Dafoe DC, Alfrey EJ. Dual kidney transplantation: older donors for older recipients. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189(1):82–91. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00073-3. discussion 91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai DM, Scandling JD, Alfrey EJ, Pavlakis M, Salvatierra O, Jr, Conley SB, Tanney DC, Dafoe DC. Kidney and kidney/pancreas transplantation at Stanford University Medical Center. Clin Transpl. 1997:135–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfrey EJ, Lee CM, Scandling JD, Pavlakis M, Markezich AJ, Dafoe DC. When should expanded criteria donor kidneys be used for single versus dual kidney transplants? Transplantation. 1997;64(8):1142–1146. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfrey EJ, Boissy AR, Lerner SM, Dual Kidney Registry Dual-kidney transplants: long-term results. Transplantation. 2003;75(8):1232–1236. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000061786.74942.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan JC, Alfrey EJ, Dafoe DC, Millan MT, Scandling JD. Dual-kidney transplantation with organs from expanded criteria donors: a long-term follow-up. Transplantation. 2004;78(5):692–696. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000130452.01521.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slooff MJ, van der Wijk J, Rijkmans BG, Kootstra G. Machine perfusion versus cold storage for preservation of kidneys before transplantation. Arch Chir Neerl. 1978;30(2):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Opelz G, Terasaki PI. Advantage of cold storage over machine perfusion for preservation of cadaver kidneys. Transplantation. 1982;33(1):64–68. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuoka L, Shah T, Aswad S, Bunnapradist S, Cho Y, Mendez RG, Mendez R, Selby R. Pulsatile perfusion reduces the incidence of delayed graft function in expanded criteria donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(6):1473–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schold JD, Kaplan B, Howard RJ, Reed AI, Foley DP, Meier-Kriesche HU. Are we frozen in time? Analysis of the utilization and efficacy of pulsatile perfusion in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(7):1681–1688. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholson ML, Hosgood SA, Metcalfe MS, Waller JR, Brook NR. A comparison of renal preservation by cold storage and machine perfusion using a porcine autotransplant model. Transplantation. 2004;78(3):333–337. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128634.03233.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]