Non-pharmacological interventions may be as important as—or even more important than—drugs and vaccines in fighting pandemic flu, speakers at a conference in Barcelona said last week.

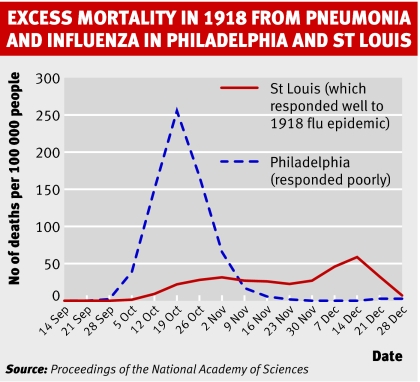

The international conference on health technology assessment heard from James LeDuc, a professor at the University of Texas who until recently helped to lead the US national strategy for responding to pandemic flu, how St Louis did much better than Philadelphia in the 1918 pandemic—long before effective drugs and vaccines were available. St Louis had its first cases on 5 October 1918, and on 7 October it took a range of measures, such as closing schools, theatres, and dance and pool halls and banning public gatherings, including funerals. In contrast, Philadelphia had its first cases on 17 September but didn't act until 3 October, and on 28 September a city-wide parade was held. St Louis experienced fewer cases and a much slower increase in the number of cases. Comparisons of the spread of flu in other US cities in 1918 supported the case for “social distancing.”

Some scientists have proposed that a pandemic might be prevented by drug treatment on a “massive” scale when it becomes clear that the virus is beginning to spread among humans. Professor LeDuc was sceptical, however, pointing out that the success of such a strategy would depend on first class surveillance, international cooperation, adequate human resources and funding, and possibly a huge transfer of drugs from one country to another. It's hard to believe that all these assumptions will be met, he said.

Social distancing will be important not just to help reduce numbers of cases but also to slow the spread of the epidemic, buying time for the production of a vaccine. It is likely to take at least six months to produce a vaccine.

Social distancing would include isolation of infected people, quarantine of their contacts, requirements for people to work from home, and probably the closure of schools and the cancellation of large gatherings. Professor LeDuc emphasised, however, that closing schools might have adverse consequences: poorer children in the United States get much of their food from schools, and single parents with jobs would struggle to cope. Also included in a social distancing programme will be the use of face masks, “cough etiquette,” hand hygiene, and disinfection of surfaces.

Clifford Goodman, a senior scientist with the Lewin Group, a healthcare consultancy firm that is based in Virginia, urged his colleagues in health technology assessment to think broadly beyond drugs and vaccines. Those involved in planning for the expected pandemic face a severe “moving target problem,” he said, and the possible responses are also constantly changing.

He emphasised—and Professor LeDuc agreed—that the virus that eventually causes the pandemic may not be a variant of H5N1, as has been widely expected, but another strain altogether. He then spelt out the importance of drug resistance: by the time the pandemic arrives (and everybody thinks it inevitable) the virus may be resistant to the drugs now available.

Dr Goodman also criticised the system of vaccine production. It was, he said, 50 years old and badly needed modernising. He then presented data on the effectiveness of vaccines (what happens in ordinary care) and on their efficacy (what happens in optimal conditions) and showed that their effectiveness was very low.

Countries cannot rely on vaccines and drugs but must plan for other interventions, including “social distancing,” he concluded.

RS chaired the conference's session on pandemic flu, and his expenses were paid by the organisers of the conference.