Abstract

Deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1 is frequently observed in neuroblastoma (NB). We performed loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis of 120 well characterized NB to better define specific regions of 1p loss and any association with clinical and biological prognostic features (DNA index, MYCN, age, and stage). All categories of disease were represented including 7 ganglioneuromas, 8 stage 4S, 33 local-regional (stages 1, 2, and 3), and 72 stage 4 NB according to the International Neuroblastoma Staging System. Patients were consistently treated with stage-appropriate protocols at a single institution. Sixteen highly informative, polymorphic loci mapping to chromosome 1 were evaluated using a sensitive, semiautomated, fluorescent detection system. Chromosome arm 1p deletions were detected in all categories of tumor except ganglioneuroma. Frequent LOH was detected at two separate regions of 1p and distinct patterns of losses were associated with individual clinical/biological categories. Clinically aggressive stage 4 tumors were predominantly diploid with extensive LOH frequently detected in the region of 1ptel to 1p35 (55%) and at 1p22 (56%). The shortest region of overlap for LOH at 1p36 was between D1S548 and D1S1592 and for 1p22 was between D1S1618 and D1S2766. Local-regional tumors were mostly hyperdiploid with short regions of loss primarily involving terminal regions of 1p36 (42%). Most spontaneously regressing stage 4S tumors (7/8) were hyperdiploid without loss of 1p36 or 1p22. These findings suggest that genes located on at least two separate regions of chromosome arm 1p play a significant role in the biology of NB and that distinct patterns of 1p LOH occur in individual clinical/biological categories.

Neuroblastoma (NB) is a pediatric cancer that arises from precursor cells of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system. It is clinically heterogeneous with at least three well recognized patterns of disease: i) infants with widespread disease that can spontaneously regress without medical intervention (stage 4S); ii) local-regional disease that may recur but does not metastasize to bone or bone marrow (stages 1, 2, and 3); and iii) systemic disease with widespread metastasis that responds to cytotoxic therapy but frequently becomes resistant to medical treatment (stage 4). This clinical variability is likely reflected in a complex molecular genetic profile that is distinct for each pattern of disease.

Several nonrandom genetic events are associated with NB, including allelic losses at chromosomes 1p, 11q, 14q, 9p, 9q, 2q, and 18q, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 gains at chromosomes 17q, 18q, 1q, 7, and 5q, 8, 9, 10, 11 amplification of the oncogene MYCN, 12 and altered DNA index. 13 MYCN amplification is associated with poor prognosis, but the relationship of other genetic events to the natural history of neuroblastoma has not been firmly established. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at 1p is commonly detected in NB, suggesting the presence of one or more tumor suppressor genes. Several distinct regions of 1p LOH have been reported in NB. The most common region of loss maps to 1p36.2–3 and the majority of studies have focused on this site. Loss of 1p in NB has been associated with gains at 17q, 3, 10 MYCN amplification 14, 15 and prognosis in some studies. 3 Despite intensive efforts, no specific gene on 1p that plays a role in NB has been identified.

To further define regions of 1p LOH and their relationship to clinical and biological features of this disease, we performed genetic analysis of 120 well-characterized NB with 16 microsatellite markers from chromosome 1. This analysis involves uniformly staged and treated patients from a single institution with a median follow-up of 43 months. Results are correlated with clinical and biological features.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Tissue and Clinical Characteristics

One hundred twenty tumor samples from patients with NB treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1987 to 1997 were used. Matched normal tissue was obtained from peripheral blood or bone marrow uninvolved by tumor. All marrow samples for stage 4 patients were screened by immunofluorescence to verify absence of tumor cells as previously described. 16 Patients were staged by the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS). 17 The study included 7 patients with ganglioneuroma, 8 patients with stage 4S, 33 patients with local-regional disease (stages 1, 2, and 3), and 72 patients with stage 4 NB. Ninety tumor samples were obtained at the time of diagnosis before any chemotherapy, 18 samples were obtained at the time of relapse, and 12 samples were obtained at the time of the second-look surgery during chemotherapy. All samples were evaluated histologically and only specimens with >50% tumor cell content were studied, most with >75%.

Clinical and biological characteristics of each case are summarized in Table 1 . Standard treatment consisted of surgical resection only for local-regional disease (stages 1, 2, and 3), ganglioneuromas, and stage 4S disease and the use of an intensive chemo-radiotherapy regimen for stage 4 disease. 18, 19

Table 1.

Relationship of LOH at 1p36 and 1p22 to Clinical and Biological Characteristics

| LOH 1p36 | P value | LOH 1p22 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| M | 63 (52.5%) | ||||

| F | 57 (47.5%) | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <1y | 31 (25.8%) | 13/31 (42%) | 0.83 | 8/31 (25%) | 0.04 |

| 1–10y | 81 (67.5%) | 41/89 (46%) | 43/89 (48%) | ||

| >10y | 8 (6.6%) | ||||

| Stage | |||||

| 4S | 8 (7.1%) | 0 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.001 |

| LR | 33 (29.2%) | 14/33 (42%) | 10/33 (30%) | ||

| 4 | 72 (63.7%) | 40/72 (55%) | 41/72 (56%) | ||

| N/A | 7 | ||||

| MYCN | |||||

| <10/hapl | 90 (75.6%) | 31/90 (34%) | 0.001 | 29/90 (32%) | 0.001 |

| >10/hapl | 29 (24.4%) | 22/29 (75%) | 21/29 (72%) | ||

| N/A | 1 | ||||

| Ploidy | |||||

| triploid | 36 (49.3%) | 12/36 (33%) | 0.21 | 13/36 (36%) | 0.67 |

| di/tetra | 37 (50.7%) | 29/62 (46%) | 26/62 (42%) | ||

| N/A | 47 |

N/A, not available for analysis.

Allelic Analysis

Primer sequences for polymorphic microsatellite loci were obtained from the Genome Data Base (Table 2) . Chromosomal map locations of loci were taken from available references: Genemap98 for chromosome 1 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genemap98/), White et al, 20 Maris et al, 21 Matise TC (http://linkage.rockefeller.edu/chr1/data/genmap/chr1), and Marshfield Genetic map for chromosome 1 (www.marshmed.org/genetics/maps). Markers were initially selected to provide relatively even distribution throughout 1p at 10 to 20-cM intervals and including regions previously determined to be frequently lost in NB. Additional markers were selected to further map regions of frequent loss identified in the initial screen of this study group. Highly informative microsatellite markers were chosen and all primer pairs were tested against a panel of normal tissues for agreement with published allelic sizes, degree of heterozygosity, and reproducibility. The National Institutes of Health genemap98 was used to order markers for Figures 2 3 4 5 .

Table 2.

Allelic Markers

| Locus | Chromosomal location | Type | HET | Anneal temp. | Size | GDB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIS80 | 1p36-pter | VNTR | 0.81 | 58 | 430-750 | G00-178-639 |

| D1S548 | 1p36.2-pter | TETRA | 0.76 | 58 | 148-172 | G00-689-691 |

| D1S1592 | 1p36.2 | TETRA | 0.67 | 58 | 232-244 | G00-684-324 |

| D1S552 | 1p36.2 | TETRA | 0.81 | 60 | 244-256 | G00-686-946 |

| D1S511 | 1p36.1 | DI | 0.57 | 55 | 218-230 | G00-200-139 |

| MycL | 1p34 | TETRA | 0.87 | 60 | 140-209 | G00-188-645 |

| D1S1669 | 1p31 | TETRA | 0.75 | 60 | 295 | G00-685-368 |

| D1S1596 | 1p31 | TETRA | 0.71 | 58 | 105-125 | G00-684-588 |

| D1S481 | 1p22 | DI | 0.86 | 60 | 235-255 | G00-199-861 |

| DIS2766 | 1p22 | DI | 0.8 | 60 | 183-195 | G00-610-932 |

| D1S1618 | 1p22 | TRI | 55 | 240 | G00-364-883 | |

| D1S1673 | 1p22 | TETRA | 60 | 234 | G00-365-513 | |

| D1S2627 | 1p22 | DI | 0.7 | 60 | 265-279 | G00-603-278 |

| D1S435 | 1p13 | DI | 0.73 | 60 | 157-177 | G00-199-326 |

| D1S1602 | centr-1p22 | TETRA | 0.73 | 60 | 395 | G00-364-279 |

| D1S547 | 1qter | TETRA | 0.68 | 60 | 282-308 | G00-686-643 |

HET, heterozygosity rates; GDB, Genome Data Base.

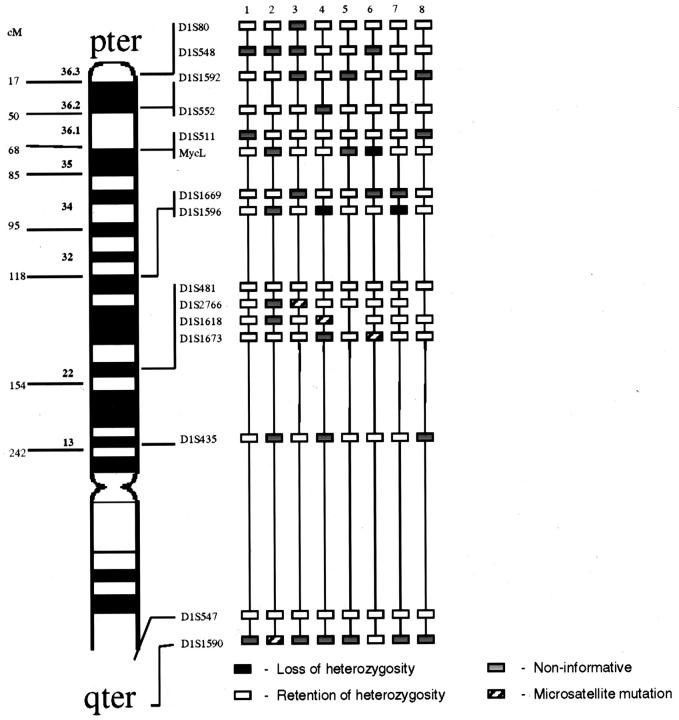

Figure 2.

LOH analysis for stage 4S patients. Approximate map location of polymorphic markers is shown at the left. Black boxes represent LOH, gray boxes are non-informative loci, white boxes are retained heterozygosity, and hatched boxes indicate microsatellite mutations.

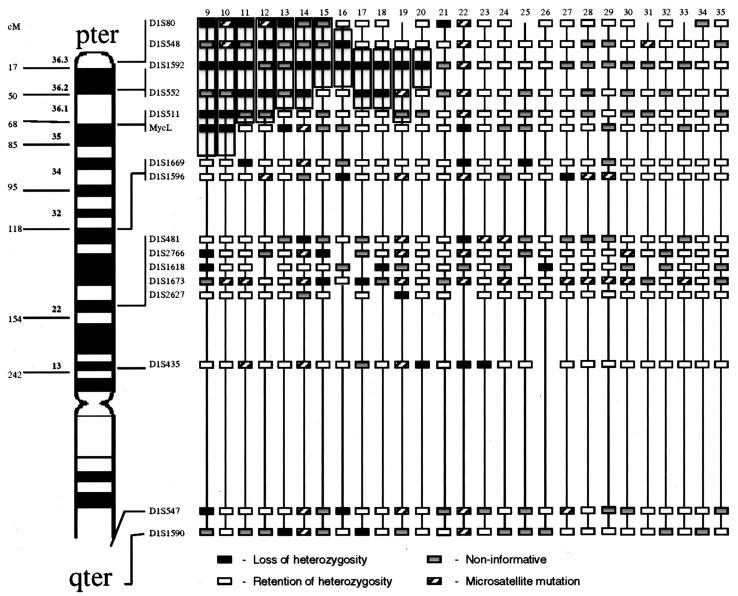

Figure 3.

Local-regional tumors with LOH at diagnosis. Approximate map location of polymorphic markers is shown at the left. Shading highlights the region of potential loss at 1p36, the most commonly deleted area, and defines the shortest region of overlap. Black boxes represent LOH, gray boxes are non-informative loci, white boxes are retained heterozygosity, and hatched boxes indicate microsatellite mutations.

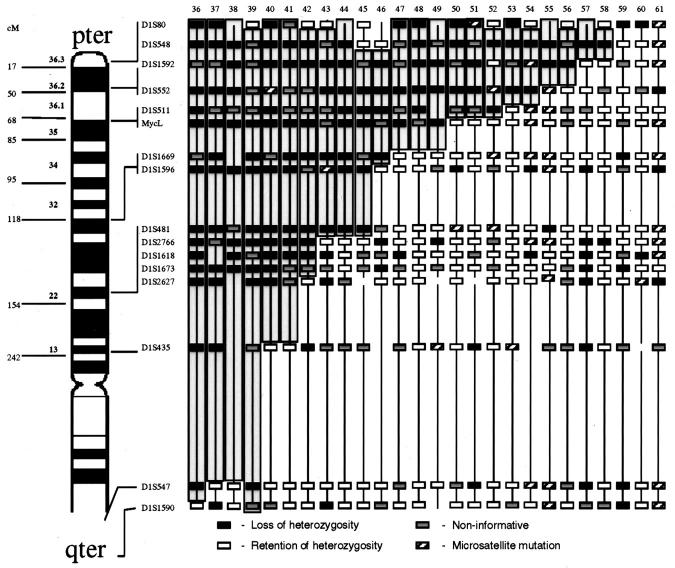

Figure 4.

Stage 4 tumors at diagnosis with LOH involving shortest region of overlap on 1p36. Approximate map location of polymorphic markers is shown at the left. Shading highlights the region of potential loss within 1p36 and defines the shortest region of overlap. Black boxes represent LOH, gray boxes are non-informative loci, white boxes are retained heterozygosity, and hatched boxes indicate microsatellite mutations.

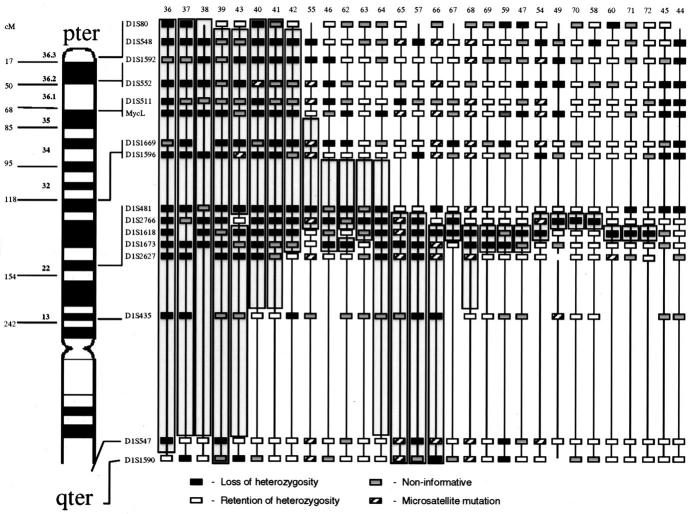

Figure 5.

Stage 4 tumors at diagnosis with LOH involving shortest region of overlap on 1p22. Approximate map location of polymorphic markers is shown at the left. Shading highlights the region of potential loss within 1p22 and defines the shortest region of overlap. Black boxes represent LOH, gray boxes are non-informative loci, white boxes are retained heterozygosity, and hatched boxes indicate microsatellite mutations.

Genomic DNA from frozen tumors, bone marrow, and peripheral blood was extracted using standard procedures. 22 Between 50 and 100 ng of template DNA was amplified on a geneAmp PCR system 9700 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT) for 35 cycles with AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems Division of Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA) using conditions recommended by the manufacturer for all of the loci examined except for D1S80 (see Table 1 ). D1S80 loci was amplified according to Peter et al 23 with only 5 ng template DNA to avoid preferential allelic amplification. One primer from each marker pair was differentially end-labeled with 6-FAM or HEX (Research Genetics) to allow coelectrophoresis of PCR products. Markers D1S80 and D1S481 were labeled during PCR with fluorescent dNTP (dUTP set; Applied Biosystems) according to standard protocol. Matched tumor and constitutional DNA were amplified individually with each marker. PCR products were pooled volumetrically along with an internal size standard (genescan Tamra 500/1000; Applied Biosystems), denatured with deionized formamide and analyzed on an ABI model 310 automated fluorescent DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) with Genescan software (Applied Biosystems).

Loss of heterozygosity was determined by comparison of the allelic ratio between the normal and tumor in heterozygous samples as previously described and validated for quantitative reproducibility. 24 Loss of heterozygosity was defined as ratios >1.5 for loss of the shortest allele or <0.5 for the largest in cases of diploid tumor content. Eighty percent of allelic ratios in diploid tumors with LOH were <0.25 or >1.75. For hyperdiploid (mostly triploid) tumors ratios of <0.35 and >2.0 were used to match the criteria for diploid tumors. Detection of allelic products in tumor samples not present in the germline control were considered microsatellite mutation.

Determination of MYCN Copy Number and DNA Index

MYCN copy number was determined by Southern blot, quantitative PCR, or fluorescence in situ hybridization as described. 12, 25, 26 A tumor was considered amplified if the MYCN copy number was >10. DNA index was determined by flow cytometry as described. 27

Statistical Analysis

To examine the association between allelic loss in a specific region and factors such as ploidy, MYCN, and stage, Fisher’s Exact test was performed and two-sided P values were computed. The association between survival, defined as the time to death or last follow-up and allelic loss in a region was assessed using the log rank test. 28 A permutation test 29 based on the log-rank statistic was used to compare the survival rates between the allelic loss/no loss groups. This application of the permutation procedure was due to the small number of deaths in the data set, a situation where the conventional log-rank test is unreliable. 30

Results

LOH on Chromosome 1p in Neuroblastic Tumors

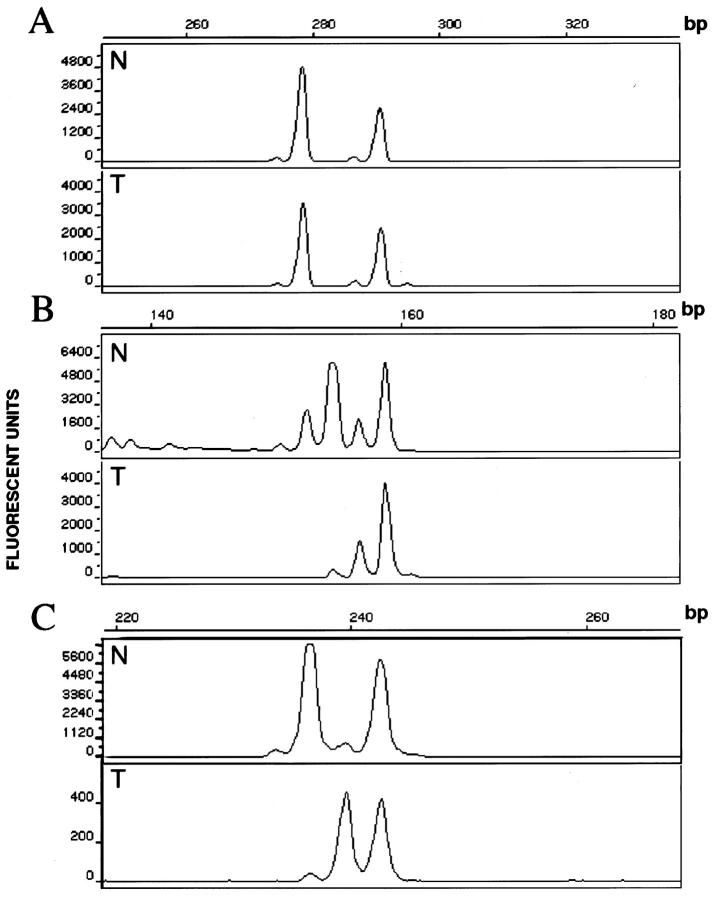

One hundred twenty NB were screened for LOH using a panel of microsatellite markers mapping to chromosome 1 (Table 2) . Representative electropherograms are presented in Figure 1 . LOH was detected in all categories of the disease except ganglioneuroma. The highest incidence of loss involved two regions, 1p36 (D1S80 to D1S511) and 1p22 (D1S481 to D1S1673). The pattern of regional LOH on chromosome 1p was distinctive for the clinical/biological subgroups of NB. In stage 4s tumors only losses at single loci (MycL and D1S1596) were detected in 3 of 8 cases without losses at 1p36 or 1p22 (Figure 2) . In local-regional tumors the highest incidence of loss was detected in the region of 1p36 (14/33, 42%) with the shortest region of overlap (SRO) for LOH, defined by regions composed of at least two contiguous informative loci with LOH located between D1S552 and D1S548 (Figure 3) . In general, local-regional NB were affected by relatively short terminal losses, although occasional more extensive LOH and interstitial LOH were detected.

Figure 1.

Representative electrophoretic profiles of microsatellite marker products A: Retained heterozygosity. B: Loss of heterozygosity. C: Microsatellite mutation. N, germline allelotype; T, tumor allelotype.

Among the stage 4 patients analyzed, 40 of 72 (55.5%) showed detectable LOH at 1p36 with the SRO between D1S1592 and D1S548 (Figure 4) . This frequency of LOH is slightly higher than the 30 to 52% previously reported in other studies (Table 4) . In addition, 41 of 72 (56%) stage 4 NB demonstrated LOH at 1p22 with the SRO bounded distally by marker D1S2766 and proximally by D1S1618 (Figure 5) . Although the occurrence of LOH at both 1p36 and 1p22 were statistically associated (P = 0.001) and in some cases contiguous, twelve stage 4 tumors had losses at 1p22 but did not show detectable losses at 1p36, whereas 10 cases exhibited loss at 1p36 but not at 1p22 suggesting two distinct regions affected by LOH. Approximately 10% of cases exhibited noncontiguous allelic LOH not involving either the 1p22 or 1p36 SRO or interstitial retained heterozygosity. These losses and retained alleles were not consistent in location and may represent random genetic alterations but were not further mapped. Sixteen of the 72 stage 4 tumors (22%) did not show loss at any of the loci analyzed. Among these: 3 tumors had 3 or more contiguous noninformative loci. Because it would be statistically improbable for this to occur with highly polymorphic loci, this finding suggests the possibility of regional losses of genetic material in germline DNA with duplication of the retained chromosomal region.

Table 4.

Selected Literature Review

| Report* | Number of cases | Region of study | Staging system | LOH by stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schleiermaier, 1994 (53) | 60 | 1p36 to 1p32 | Forbeck | II/4S: 2/20 (10%) |

| III/IV: 20/40 (50%) | ||||

| Takeda, 1994 (15) | 108 | 1p36 to 1q23 | Evans | I/II/IVS: 6/49 (12%) |

| III: 4/18 (22%) | ||||

| (LR: 10/67 15%) | ||||

| IV: 11/37 (30%) | ||||

| Caron, 1995 (57) | 55 | 1p36 | Evans | IVS: 2/6 (33%) |

| I/II: 3/16 (18%) | ||||

| (LR: 5/22 (22%) | ||||

| III/IV: 15/33 (45%) | ||||

| Martinsson, 1995 (60) | 51 | 1p36 to 1p34 | INSS | 4S: 0/1 |

| 1,2,3: 1/24 (4%) | ||||

| 4: 11/21 (52%) | ||||

| Gehring, 1995 (55) | 51 | 1q to 1p36 | Evans | IVS: 1/3 (33%) |

| I,II,III: 4/18 (22%) | ||||

| IV: 12/30 (40%) | ||||

| White, 1995 (20) | 122 | 1p36 | N/A | no stage breakdown |

| 32/122 (26%) | ||||

| 25 of the 32 had MYCN A | ||||

| Maris, 1995 (21) | 156 | 1p36 | POG | A,B,DS: 4/74 (5%) |

| C,D: 26/82 (32%) | ||||

| 18/26 MYCN A (67%) | ||||

| 12/126 MYCN NA (10%) | ||||

| Caron, 1996 (57) | 89 | 1p36 | Evans | I,II,IVS: 10/37 (27%) |

| II,IV: 19/52 (36%) | ||||

| Iolascon, 1998 (54) | 53 | 1p36 to 1p34 | INSS | 1,2,4S: 7/27 (26%) |

| 3,4: 12/26 (46%) | ||||

| 14/53 MYCN A (26%) | ||||

| 10/14 MYCN A = LOH (71%) | ||||

| Mora, 2000 | 120 | 1p36 to 1q | INSS | 1p36: |

| 4S: 0/8 (0%) | ||||

| 1,2,3: 14/33 (42%) | ||||

| 4: 40/72 (55%) | ||||

| 1p22: | ||||

| 4S: 0% | ||||

| 1,2,3: 10/33 (30%) | ||||

| 4: 41/72 (56%) |

Reports are listed by first author, year of publication, and reference list number.

Mutation of microsatellites (MM), defined as the presence of non-germline alleles, were detected in some NB. It is interesting that one allele with frequent MM in local-regional tumors, D1S1673, was commonly lost in stage 4 cases. A small subset of cases, 19 of the 120 (15%), exhibited a high degree of MM (>30% of the markers tested). These mutations affected di-, tri-, and tetra-nucleotide repeats, but not mononucleotide repeat microsatellites (data not shown) suggesting a mechanism of MM different from that associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Alternatively, this may represent extensive spontaneous mutation stabilization within the malignant tumor. The incidence of extensive MM was similar among the three categories of disease: 1 stage 4s (12.5%), 4 local-regional (12%), and 14 stage 4 patients (19%).

1p LOH Correlation with Clinical, Biological, and Genetic Features

Loss at 1p36 strongly correlated with survival (event defined as death from disease, P = 0.002), whereas loss at 1p22 (P = 0.19) or loss at 1p36 or 1p22 (P = 0.08) were less strongly associated (see Table 3 ). LOH at region 1p36 or 1p22 was associated with stage 4 (P = 0.001; see Table 1 ). When stage 4 cases were analyzed alone, losses at 1p36 (P = 0.004), losses at 1p22 (P = 0.001), and losses at both (P = 0.004) were associated with survival.

Table 3.

Survival Analysis

| Locus of LOH | Patients | Died |

|---|---|---|

| LOH in 1p36 | ||

| Yes | 54 | 19 |

| No | 66 | 10 |

| P value = 0.002 | ||

| LOH in 1p22 | ||

| Yes | 51 | 15 |

| No | 69 | 14 |

| P value = 0.19 | ||

| LOH in 1p36 or 1p22 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 21 |

| No | 50 | 8 |

| P value = 0.08 |

Twenty-nine MYCN-amplified tumors were available for study, including 3 local-regional and 26 stage 4 cases. All were diploid and 26 (89%) had detectable losses at one or more loci on 1p, a higher incidence of detectable LOH than the non-amplified group (42%). LOH at either 1p36, 1p22 or both strongly correlated with MYCN amplification (P = 0.001). Tumor DNA index was determined in 74 cases (see Table 1 ). Seven of 8 (87.5%) stage 4S, 24 of 33 (73%) local-regional, and 5 of 33 (15%) stage 4 patients were found to be hyperdiploid, mostly near triploid. Although numbers are too small for meaningful statistical analysis, diploid local-regional tumors (9/33) presented a higher incidence of MYCN amplification (3/9), multiple relapses (4/9), and poorer prognosis (2 dead/9) than hyperdiploid local-regional tumors. Infants less than 1 year of age (n = 31) showed a striking correlation between stage and DNA index: all stage 4 infants (n = 10) were diploid, whereas all but 1 stage 4S were triploid (P = 0.002). Of interest DNA index (diploid versus aneuploid) was not associated with LOH.

Discussion

Using allelic analysis, we detected distinct patterns of LOH on chromosome 1p associated with different clinical and biological categories of NB. LOH was found among all categories of NB except ganglioneuromas, suggesting that loss of chromosome 1p is a common event in NB tumorigenesis. In tumors from patients with spontaneously regressing 4S disease, only rare LOH was detected involving MycL and D1S1596 with preservation of all other chromosome 1 loci tested. For local-regional tumors (those that do not produce distant metastasis), there was a moderate frequency of LOH primarily due to small terminal losses in the 1p36 region with rare losses detected at other chromosomal loci. LOH was most frequent in stage 4 NB with extensive loss detected involving two regions, 1p36 and 1p22. LOH at 1p36 was found to strongly correlate with survival. Loss at 1p36 and at 1p22 were statistically associated with stage 4 disease and MYCN amplification. MYCN amplification was present in a subset of cases highly affected by 1p deletion, suggesting MYCN amplification as a subsequent event in NB progression. However, it should be noted that amplification of MYCN has not been detected in recurrence of previously unamplified tumors.

The multistep nature of cancer progression is thought to be a consequence of genomic instability. 31 Two main genomic instability phenotypes have been described, the chromosomal (CIN) and the molecular instability (MIN) phenotypes. The hallmark for CIN is aneuploidy and the underlying mechanism is believed to be the loss of function of mitotic checkpoint genes. 32 MIN results in more subtle sequence alterations such as amplifications, deletions or insertions and the responsible mechanism is still unclear. Pathways leading to CIN and MIN phenotypes are not mutually exclusive and they have common end points, such as LOH. 33

Likewise, two genetically distinct categories of neuroblastoma can be identified: those with gross abnormalities in chromosome number characterized by hyperdiploidy (primarily stage 4s, and most local-regional tumors) and those that are characteristically diploid but frequently have regional amplifications and deletions (primarily stage 4 tumors). Each of these groups has distinct clinical behavior with significant differences in survival rates. 34 Hyperdiploid tumors have a relatively benign biological behavior, with a tendency to regress spontaneously (stage 4s), or mature (stages 1, 2, and 3) and do not require cytotoxic treatment to achieve cure rates exceeding 95%. 34 The diploid group is primarily composed of tumors that are clinically aggressive with poor prognosis despite multimodal therapy. 18, 19 Different mechanisms of 1p LOH, either CIN or MIN, may be responsible for the different pattern of loss for each genetic subgroup of NB, although we did not detect any relationship between DNA index and LOH. In addition, the biological significance of specific LOH may differ among the genetic subgroups, eg, LOH detected in a triploid tumor may not have the same effect as that in a diploid tumor based on gene dosage alone.

Nonrandom LOH of a specific chromosomal region in a given tumor type suggests the presence of tumor suppressor genes that play a role in the biology of that tumor. Hot-spots for genomic alteration have been described for various tumors 35, 36 and may include genes affecting pathways common to cancer biology such as cell cycle regulation, mechanisms of invasion, and metastasis. For instance, several regions of chromosome 1p, including 1p36 and 1p22, have been implicated in the tumorigenesis of a wide range of malignancies. 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 Prior LOH studies in NB have used a variety of techniques and most have focused on 1p36. The incidence of 1p36 LOH in the literature ranges from 19 to 36%. In our series there is an overall incidence of LOH at 1p36 of 45%. This somewhat higher incidence may be due to increased attention to selection of samples with a higher percentage of tumor cells, analysis of a different set of markers and the use of a sensitive, quantitative technique. Another possibility is that there could be an unintentional bias toward high risk patients in our study group, because such patients are often referred to specialized cancer centers. However, when compared to a reference distribution 50 our patient population has a similar stage distribution. It is difficult to compare stage-specific LOH between the various studies due to different groupings used by investigators. Reports in the literature (see Table 4 ) often group stage 4S, 1, and 2 as low stage and report an incidence of 5 to 27% 1p36 LOH. We detected an incidence of 32% for LOH at 1p36 for stages 4s (0/8), 1 (0/6), and 2 (9/15). In stages 3 and 4, grouped as advanced stage in many studies, there is a reported incidence of 30 to 52%, whereas we have an incidence of 52% for stages 3 and 4 combined. The clinical grouping we use in Figures 2 3 4 and 5 is based on our current approach to therapy. Stages 4S, 1, 2, and 3 are initially treated without cytotoxic therapy, whereas stage 4 patients receive an intense multimodality regimen. All clinical correlations in this study were therefore based on a consistent therapeutic approach according to clinical group and avoided issues of a heterogeneously treated population.

At least two regions of 1p have previously been suggested to be important in NB based on LOH. One region of high incidence of LOH is at 1p36.2–3 and another is encompassed by larger deletions extending to 1p32. 14, 15, 51, 52, 53 We also detected varying lengths of deletions of 1p36 with low risk tumors primarily exhibiting shorter regions of contiguous loss, but this association did not reach statistical significance. In addition, our study detected a high incidence of LOH at 1p22 apparently distinct from LOH at 1p36. LOH and translocation at 1p22 have been implicated in the tumorigenesis of NB before, but has not been thoroughly studied in a large group of cases 2, 53, 54, 55, 56 . Our data suggest a more common involvement of this region in NB than previously identified.

The clinical significance of LOH at specific regions of 1p is still a matter of debate. Losses of 1p have been correlated with advanced stages and poor prognosis in some studies 3, 21, 54, 57 and larger losses are associated with MYCN amplification. 14, 15, 52, 58 Other investigators however have not identified an association between LOH and MYCN amplification 21 or prognosis. 58 For local-regional tumors and stage 4S, the data are less clear, although some groups have correlated 1p LOH with poor prognosis in low-risk groups. 2 In the present study composed of cases consistently treated at a single institution, LOH of 1p36 and 1p22 was associated with stage and MYCN amplification and LOH of 1p36 was associated with survival (See Tables 1 and 3 ). Because of the very small number of events in the low-risk group, we analyzed the association between LOH at 1p36 or 1p22 and survival in stage 4 patients only and found both to be statistically significant.

Recently gain of 17q has been found to be associated with adverse outcome in NB. 59 This genetic abnormality is commonly due to an unbalanced translocation with a variety of partner chromosomes including chromosome 1. Gain of 17q is associated with advanced disease, age greater than 1 year, deletion of 1p, and amplification of MYCN. In that study 47% of tumors were determined to have 1p36 deletion and 1p loss was associated with decreased 5-year survival. These findings are in good agreement with the present study.

Our analyses of multiple allelic markers on chromosome 1 show that clinically distinct groups display very different patterns of LOH. LOH of 1p was detected in all clinical stages, consistent with the hypothesis that 1p deletion may be an early event in NB tumorigenesis and two regions of frequent LOH were identified. The pattern of LOH on chromosome 1p together with the DNA index appeared to define two genetic groups of tumors of potential clinical significance. The hyperdiploid group of tumors is comprised of mostly INSS stages 1, 2, and 3, with a moderate frequency of LOH primarily limited to 1p36, and stage 4S tumors, with losses confined to 1p31 region and no detectable losses at 1p36 or 1p22. Most patients in this group do not require cytotoxic therapy and achieve an overall survival rate of >95%. 34 The diploid group of tumors, mostly INSS stage 4, presented a high incidence of LOH with large deletions at both 1p36 and 1p22. This group of tumors has MYCN oncogene amplification in a subset of cases (36%). Clinically these are very aggressive and even with intense multimodality cytotoxic therapy they achieve an overall survival rate of only 40%. 18

The results reported here show a significant correlation between genetic markers such as 1p LOH and DNA ploidy, with clinically relevant groups of NB. The genetic identification of clinically distinct tumors could provide useful objective diagnostic and prognostic markers for improved classification and risk stratification of individual NB patients.

Address reprint requests to Dr. William L. Gerald, Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021. E-mail:geraldw@mskcc.org.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Justin Zahn Fund, the Robert Steel Foundation, Katie’s Find A Cure Fund, and National Institutes of Health grant CA61017.

References

- 1.Fong CT, White PS, Peterson K, Sapienza C, Cavenee WK, Kern SE, Vogelstein B, Cantor AB, Look AT, Brodeur GM: Loss of heterozygosity for chromosomes 1 or 14 defines subsets of advanced neuroblastomas. Cancer Res 1992, 52:1780-1785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maris JM, Matthay KK: Molecular biology of neuroblastoma. JCO 1999, 17:2264-2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caron H: Allelic loss of chromosome 1 and additional chromosome 17 material are both unfavorable prognostic markers in neuroblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 1995, 24:215-221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert F, Feder M, Balaban G, Brangman D, Lurie K, Podolsky R, Rinaldt V, Vinikoor N, Weisband J: Human neuroblastomas and abnormalities of chromosomes 1 and 17. Cancer Res 1984, 44:5444-5449 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takayama H, Suzuki T, Mugishima H, Fujisawa T, Ookuni M, Schwab M, Gehring M, Nakamura Y, Sugimura T, Terada M, Yokota J: Deletion mapping of chromosomes 14q and 1p in human neuroblastoma. Oncogene 1992, 7:1185-1189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall B, Isidro G, Martins AG, Boavida MG: Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 9p21 in primary neuroblastomas: evidence for two deleted regions. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1997, 96:134-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takita J, Hayashi Y, Kohno T, Yamaguchi N, Hanada R, Yamamoto K, Yokota J: Deletion map of chromosome 9 and p16 (CDKN2A) gene alterations in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 1997, 57:907-912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meltzer SJ, O’Doherty SP, Frantz CN, Smolinski K, Yin J, Cantor AB, Liu J, Valentine M, Brodeur GM, Berg PE: Allelic imbalance on chromosome 5q predicts long-term survival in neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer 1996, 74:1855-1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meddeb M, Danglot G, Chudoba I, Vénuat AM, Benard J, Avet-Loiseau H, Vasseur B, Paslier DL, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Hartmann O, Bernheim A: Additional copies of 25 Mb chromosomal region originating from 17q23.1–17qter are present in 90% of high grade neuroblastomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1996, 17:156-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plantaz D, Mohapatra G, Matthay K, Pellarin M, Seeger RC, Feuerstein BG: Gain of chromosome 17 is the most frequent abnormality detected in neuroblastoma by comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:81-89 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandesompele J, Van Roy N, Van Gele M, Laureys G, Ambros PO, Heimann P, Devalck C, Schuuring E, Brock P, Otten J, Gyselinck J, De Paepe A, Speleman F: Genetic heterogeneity of neuroblastoma studied comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1998, 23:141-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeger RC, Brodeur GM, Sather H, Dalton A, Siegel SE, Wong KY, Hammond D: Association of multiple copies of the N-myc oncogene with rapid progression of neuroblastomas. N Engl J Med 1985, 313:1111-1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Look AT, Hayes FA, Nitschke R, McWilliams NB, Green AA: Cellular DNA content as a predictor of response to chemotherapy in infants with unresectable neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 1984, 311:231-235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caron H, Peter M, Van Sluis P, Speleman F, de Kraker J, Laureys G, Michon J, Brugieres L, Voute PA, Westerveld A, Slater R, Delattre O, Versteeg R: Evidence for two tumor suppressor loci on chromosomal bands 1p35–36 involved in neuroblastoma: one probably imprinted, another associated with N-myc amplification. Hum Mol Genet 1995, 4:535-539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeda O, Homma C, Maseki N, Sakurai M, Kanda N, Schwab M, Nakamura Y, Kaneko Y: There may be two tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 1p closely associated with biologically distinct subtypes of neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1994, 10:30-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung NKV, Heller G, Kushner BH, Liu C, Cheung IY: Detection of metastatic neuroblastoma in bone marrow: when is routine marrow histology insensitive? J Clin Oncol 1997, 15:2807-2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, Carlsen NLT, Castel V, Castleberry RP, De Bernardi B, Evans AE, Favrot M, Hedborg F, Kaneko M, Kemshead J, Lee REJ, Look T, Pearson ADJ, Philip T, Roald B, Sawada T, Seeger RC, Tsuchida Y, Voute PA: Revisions of the International Criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol 1993, 11:1466-1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Bonilla MA, Lindsley K, Rosenfield N, Yeh S, Eddy J, Gerald WL, Heller G, Cheung NKV: Highly effective induction therapy for stage 4 neuroblastoma in children over 1 year of age. J Clin Oncol 1994, 12:2607-2613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung NKV, Kushner BH, LaQuaglia M, Kramer K, Gollamudi S, Heller G, Gerald W, Yeh S, Finn R, Larson SM, Wuest D, Byrnes M, Dantis E, Mora J, Cheung IY, Rosenfield N, Abramson S, O’Reilly RJ: N7: a novel multi-modality therapy of high risk neuroblastoma in children diagnosed over 1 year of age. Eur J Cancer 1999 (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.White PS, Maris JM, Beltinger C, Sulman E, Marshall HN, Fujimori M, Kaufman BA, Biegel JA, Allen C, Hilliard C, Valentine MB, Look AT, Enomoto H, Sakiyama S, Brodeur GM: A region of consistent deletion in neuroblastoma maps within human chromosome 1p36.2–36.3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:5520-5524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maris JM, White PS, Beltinger CP, Sulman EP, Castleberry RP, Shuster JJ, Look AT, Brodeur GM: Significance of chromosome 1p loss of heterozygosity in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 1995, 55:4664-4669 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrock J: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 1989. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY,

- 23.Peter M, Michon J, Vielh P, Neuenschwander S, Kakamura Y, Sonsino E, Zucker JM, Vergnaud G, Thomas G, Delattre O: PCR assay for chromosome 1p deletion in small neuroblastoma samples. Int J Cancer 1992, 52:544-548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cawkwell L, Bell SM, Lewis FA, Dixon MF, Taylor GR, Quirke P: Rapid detection of allele loss in colorectal tumours using microsatellites and fluorescent DNA technology. Br J Cancer 1993, 67:1262-1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stock C, Ambros IM, Mann G, Gardner H, Amann G, Ambros PF: Detection of 1p36 deletions in paraffin sections of neuroblastoma tissues. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1993, 6:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohl N, Kanda N, Schreck RR, Bruns G, Latt SA, Gilbert F, Alt FW: Transposition and amplification of oncogene-related sequences in human neuroblastoma. Cell 1983, 35:359-367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson AE, Norton JA, Weinberg DS: Comparative assessment of proliferation and DNA content in breast carcinoma by image analysis and flow cytometry. Am J Pathol 1990, 136:1115-1124 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox DR, Oakes D: Analysis of Survival Data. 1984. Chapman Hall, London

- 29.Maritz JS: Distribution-Free Statistical Methods. 1981. Chapman Hall, London

- 30.Heller G, Venkatraman ES: Resampling procedures to compare two survival distributions in the presence of right-censored data. Biometrics 1996, 52:1204-1213 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loeb LA: Many mutations in cancers. Cancer Surv 1996, 28:329-341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature 1998, 396:643-649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: Genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nature 1997, 386:623-627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kushner BH, Cheung NKV, LaQuaglia MP, Ambros PF, Ambros IM, Bonilla MA, Gerald WL, Ladanyi M, Gilbert F, Rosenfield NS, Yeh SDJ: Survival from locally invasive or widespread neuroblastoma without cytotoxic therapy. J Clin Oncol 1996, 14:373-381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James CD, Carlbom E, Nordenskjold M, Collins VP, Cavenee WK: Mitotic recombination of chromosome 17 in astrocytomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989, 86:2858-2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwab M, Praml C, Amler LC: Genomic instability in 1p and human malignancies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1996, 16:211-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsukamoto K, Noriko I, Yoshimoto M, Kasumi F, Akiyama F, Sakamoto G, Nakamura Y, Emi M: Allelic loss on chromosome 1p is associated with progression and lymph node metastasis of primary breast carcinoma. Cancer 1998, 82:317-322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bomme L, Heim S, Bardi G, Fenger C, Kronborg O, Brogger A, Lothe RA: Allelic imbalance and cytogenetic deletion of 1p in colorectal adenomas: a target region identified between D1S199 and D1S234. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1998, 21:185-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bello J, Vaquero J, De Campos JM, Kusak ME, Sarasa JL, Saez-Castresana J, Pestana A, Rey JA: Molecular analysis of chromosome 1 abnormalities in human gliomas reveals frequent loss of 1p in oligodendroglial tumors. Int J Cancer 1994, 57:172-175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraus JA, Albrecht S, Wiestler OD, von Schweinitz D, Pietsch T: Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 1 in human hepatoblastoma. Int J Cancer 1996, 67:467-471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sulman EP, Dumanski JP, White PS, Zhao H, Maris JM, Mathiesen T, Bruder C, Cnaan A, Brodeur GM: Identification of a consistent region of allelic loss on 1p32 in meningiomas: correlation with increased morbidity. Cancer Res 1998, 58:3226-3230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khosla S, Patel VM, Hay ID, Schaid DJ, Grant CS, van Heerden JA, Thibodeau SN: Loss of heterozygosity suggests multiple genetic alterations in pheochromocytomas and medullary thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Invest 1991, 87:1691-1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balaban GB, Herlyn M: Clark Jr WH, Nowell PC: Karyotypic evolution in human malignant melanoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1986, 19:113-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hahn SA, Seymour AB, Hoque ATMS, Schutte M, da Costa LT, Redston MS, Caldas C, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, et al: Allelotype of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using xenograft enrichment. Cancer Res 1995, 55:4670-4675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sreekantaiah C, Bhargava MK, Shetty NJ: Chromosome 1 abnormalities in cervical carcinoma. Cancer 1988, 62:1317-1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iolascon A, Faienza MF, Coppola B, Moretti A, Basso G, Amaru R, Vigano G, Biondi A: Frequent clonal loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the chromosomal region 1p32 occurs in childhood T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) carrying rearrangement of TAL1 gene. Leukemia 1997, 11:359-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathew S, Murty VVVS, Bosl GJ, Chaganti RSK: Loss of heterozygosity identifies multiple sites of allele deletions on chromosome 1 in human male germ cell tumors. Cancer Res 1994, 54:6265-6269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ebrahimi SA, Wang EH, Wu A, Schreck RR, Passaro E, Sawicki MP: Deletion of chromosome 1 predicts prognosis in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Cancer Res 1999, 59:311-315 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brodeur GM, Sekhon GS, Goldstein MN: Chromosomal aberrations in human neuroblastomas. Cancer 1977, 40:22556-22263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pizzo PA, Poplack DG: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology, 3d ed. 1997. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia

- 51.Weith A, Martinsson T, Cziepluch Z, Bruderlein S, Amler LC, Berthold F, Schwab Z: Neuroblastoma consensus deletion maps to 1p36.1–2. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1989, 1:159-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng NC, Van Roy N, Chan A, Beitsma M, Westerveld A, Speleman F, Versteeg R: Deletion mapping in neuroblastoma cell lines suggests two distinct tumor suppressor genes in the 1p35–36 region, only one of which is associated with N-myc amplification. Oncogene 1995, 10:291-297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schleiermacher G, Peter M, Michon J, Hugot JP, Vielh P, Zucker JM, Magdelenat Z, Thomas G, Delattre O: Two distinct deleted regions on the short arm of chromosome 1 in neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1994, 10:275-281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iolascon A, Cunsolo C, Giordani L, Cusano R, Mazzocco K, Boumgartner M, Ghisellini P, Faienza MF, Boni L, De Bernardi B, Conte M, Romeo G, Tonini GP: Interstitial and large chromosome 1p deletion occurs in localized and disseminated neuroblastomas and predicts an unfavourable outcome. Cancer Lett 1998, 130:83-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gehring M, Berthold F, Edler L, Schwab M, Amler LC: The 1p deletion is not a reliable marker for the prognosis of patients with neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 1995, 55:5366-5369 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts T, Chernova O, Cowell JK: Molecular characterization of the 1p22 breakpoint region spanning the constitutional translocation breakpoint in a neuroblastoma patient with a t(1;10)(p22;q21). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998, 100:10-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caron H, Van Sluis P, De Kraker J, Bokkerink J, Egeler M, Laureys G, Slater R, Westerveld A, Voute PA, Versteeg R: Allelic loss of chromosome 1p as a predictor of unfavorable outcome in patients with neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 1996, 334:225-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fong CT, Dracopoli NC, White PS, Merrill PT, Griffith RC, Housman DE, Brodeur GM: Loss of heterozygosity for the short arm of chromosome 1 in human neuroblastomas: correlation with N-myc amplification. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1989, 86:3753-3757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bown N, Cotterill S, Lastowska M, O’Neill S, Pearson A, Plantaz D, Meddeb M, Danglot G, Brinkschmidt C, Christiansen H, Laureys G, Speleman F: Gain of chromosome arm 17q and adverse outcome in patients with neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 1999, 340:1954-1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinsson T, Sjoberg RM, Hedberg F, Koguer P: Deletion of chromosome 1p loci and microsatellite instability in neuroblastomas analyzed with short-tandem repeat polymorphisms. Cancer Res 1995, 55:5681-5686 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]