Abstract

The incidence of melanoma is increasing rapidly in western countries. Genetic predisposition in familial and in some sporadic melanomas has been associated with the presence of INK4A gene mutations. To better define the risk for developing sporadic melanoma based on genetic and environmental interactions, large groups of cases need to be studied. Mutational analysis of genes lacking hot spots for sequence variations is time consuming and expensive. In this study we present the application of denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) for screening of mutations. Exons 1α, 2, and 3 were amplified from 129 samples and 13 known mutants, yielding 347 products that were examined at different temperatures. Forty-two of these amplicons showed a distinct non-wild-type profile on the chromatogram. Independent sequencing analysis confirmed 16 different nucleotide variations in Leu32Pro; Ile49Thr; 88 del G; Gln50Arg; Arg24Pro; Met53Ile; Met53Thr; Arg58stop; Pro81Leu; Asp84Ala; Arg80stop; Gly101Trp; Val106Val; Ala148Thr; and in positions (−2) in intron 1 (C → T); and in the 3′ UTR, nucleotide 500 (C → G). No false negatives or false positives were obtained by DHPLC in samples with mutations or polymorphisms. We conclude that the DHPLC is a fast, sensitive, cost-efficient, and reliable method for the scanning of INK4A somatic or germline mutations and polymorphisms of large number of samples.

Cutaneous melanomas are being detected at an increasing rate worldwide. Even though many patients are diagnosed at an early stage, the death rate continues to rise due to the increasing incidence of more advanced lesions. 1, 2 Genetic and environmental factors such as family history, skin type, previous tumors, and sun exposure have been identified as important risk factors. 3, 4, 5, 6 In addition, germline mutations or variants of certain genes have been proposed as risk factors for the development of melanomas. Oneof these genes, the CDKN2A or INK4A, encodes for p16, an important cell cycle regulator capable of arresting cells in G1-phase by inhibiting the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein by cyclinD1/Cdk4 complexes. 7 The INK4A gene has been found silenced by point mutation, deletion, and methylation of the promoter region in several sporadic tumor types. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Analyses of INK4A in sporadic melanomas revealed a frequency of mutations and deletions that ranges from approximately 75% in cell lines 8 to 15% in primary multiple melanoma tumors. 17 In addition, INK4A germline mutations have been found in melanoma kindreds, ranging in prevalence from 10.3 to 72.2%, 18, 19 although in overall approximately 20% of the families that have been studied show mutations in this gene. 20

In an attempt to better define the gene-environment interactions in sporadic melanoma, our group expects to enroll 4000 newly diagnosed subjects to determine the relationship between germline INK4A mutations and environmental factors such as sun exposure. Typically, INK4A gene mutations have been analyzed by polymerase chain reaction-single stranded conformational polymorphism (PCR-SSCP) and sequencing. 16, 18, 21 Due to time and cost-effectiveness considerations, the present study was undertaken to validate the use of a relatively novel method, denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC), for the screening of INK4A gene mutations. This is a fast and sensitive method to detect variations in the DNA sequence that lead to heteroduplexes. 22, 23, 24 DNA is allowed to bind to a hydrophobic column in a buffer of triethyl ammonium acetate and is eluted with an increasing gradient of acetonitrile. Under certain key parameters including temperature and buffer concentration, partial denaturation of the double stranded DNA (dsDNA) occurs. If the sample contains heteroduplex molecules, these will denature at lower concentrations of acetonitrile, and will be visualized as a peak or peaks with shorter retention times than the homoduplexes.

No previous study has reported on the reliability of the DHPLC for detecting INK4A mutations or polymorphisms. Therefore, we evaluated the sensitivity of the method under diverse conditions and by comparing the results with those obtained by direct sequencing of DNA, in a group of 129 germline DNA samples from melanoma patients in addition to 13 known INK4A mutants. Our results show that DHPLC, under proper temperature and gradient conditions, is a reliable screening method for INK4A mutations or polymorphisms, especially in molecular epidemiology-based studies, where speed as well as cost of analysis are important based on the large number of cases examined.

Materials and Methods

DNA

DNA was obtained from blood or buccal swabs from melanoma patients. DNA from blood was extracted using the Qiagen Qiamp DNA kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA from buccal cells was isolated by placing the brushes in 600 μl of sodium hydroxide, 50 mmol/L, vortexing for 10 minutes and incubating overnight at 55°C. Next day, the tubes were centrifuged and incubated at 95°C for 15 minutes. Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) was added to a final concentration of 167 mmol/L and after vortexing briefly, the tubes were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 seconds. DNA samples from a melanoma derived cell line (SK-Mel21), 10 primary melanoma cases (F3; 1515F; 553F; 114F; 338F; 1452; 250F; 1620F; 1561F; 948F) and three primary bladder tumors (BlTm50; BlTm60; BlTm105) known to contain INK4A mutations spanning all exons were also available. 12, 25

Primers

Exons 1α, 2, and 3 of the INK4A gene and their splice junctions were analyzed using primers described by Hussussian et al 18 with few modifications. With the exception of one case, exon 2 was amplified using one set of primers (2A-forward and 2C-reverse), originating a 411-bp fragment. In one case, for sequencing analyses, additional DNA was extracted from normal keratinocytes obtained by laser-capture microdissection using an Arcturus PixCell-1 Laser Capture Microdissection System (Arcturus Engineering, Inc., Mountain View, CA), and the entire exon 2 was evaluated by amplification of three overlapping fragments. 18

PCR Reaction

Ten to 100 ng of genomic DNA were amplified in a reaction mixture containing 0.4 μmol/L for each forward and reverse primer, 200 μmol/L dNTPs (PE, Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Branchburg, NJ), 0.06 U/μl Taq polymerase (PE), 10 nmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1M betaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). 26 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mixtures were subjected to the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 minutes; 95°C for 25 seconds, 55°C for 25 seconds, 72°C for 35 seconds for 35 cycles, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 (exon 3) to 10 (exons 1 α and 2) minutes. All PCR products were tested on ethidium bromide stained agarose gels to verify the size of the amplified band. The relative amount of amplicons (those obtained from samples versus those obtained from a wild-type control) was assessed by comparing band intensities.

Denaturing HPLC Analysis

All PCR products were mixed in approximately equimolar proportions with an amplified sample known to contain a wild-type INK4A fragment. Mixed samples were heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and allowed to cool down to room temperature for approximately 20 minutes. Five to 10 μl of each sample were run on a Wave DNA Fragment Analysis System (Transgenomic, Omaha, NE) using a DNASep column and the run was monitored by ultraviolet light (260 nm). Optimum DHPLC temperatures were determined by an incremental temperature scan, using the software-predicted melting profile as a starting point. Samples were run at more than one temperature due to the heterogeneity in the distribution of GC-rich regions that results in a heterogeneous melting temperature distribution throughout the amplified DNA fragment to be analyzed. Three different temperatures were chosen for the DHPLC runs for exons 1α and 2 and two different temperatures for exon 3 (Table 1) . With these temperatures, we obtained approximately 35 to 99% of the strands in a partially denatured state, as recommended for this method. The amplicons were eluted with a linear acetonitrile gradient at a flow rate of 0.9 ml/min. The gradient duration was adjusted according to each PCR product length as detailed in Table 1 . Each elution profile or chromatogram was compared with profiles associated with homozygous wild-type sequence controls. Samples showing an altered chromatographic profile were repeated starting with a new PCR reaction. These samples were either mixed or unmixed with wild-type control. This allowed differentiating between originally heterozygote or homozygote variants.

Table 1.

Denaturing HPLC—Buffer and Temperature Conditions

| INK4A amplicon | Fragment size (base pairs)* | Buffer A (%)† | Buffer B (%)‡ | Gradient (minutes) | Time shift (minutes)§ | Temperature (°C)¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 1α | 203 | 48 | 52 | 4.5 | (−) 1 | 67 |

| 53 | 47 | 6 | None | 69 | ||

| 55 | 45 | 6 | 1 | 70 | ||

| Exon 2 | 411 | 45 | 55 | 4.5 | 1 | 65 |

| 47 | 53 | 4.5 | 2 | 69 | ||

| 47 | 53 | 4.5 | 2 | 70 | ||

| Exon 3 | 169 | 51 | 49 | 4.5 | (−) 0.5 | 59 |

| 51 | 49 | 4.5 | (−) 0.5 | 60 |

Fragment size refers to the amplified exon and surrounding nucleotides (intronic, 5′ or 3′ UTR).

Buffer A: 0.1 mol/L triethylammonium acetate (TEAA), pH 7.0.

Buffer B: 0.1 mol/L TEAA, 25% acetonitrile, pH 7.0. Percentage of buffer shown corresponds to the beginning of the gradient.

Time shift refers to the position of the homoduplex wild type peak relative to the predicted time.

Mobile phase temperature.

Sequencing Analysis

An independent PCR reaction was performed in all cases. Specific bands were gel purified with a gel purification kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Qiagen). The amount of purified DNA varied according to the fragment size and sequencing instrument used, but approximately 8 to 25 ng of each purified sample were mixed with 3.2 pmols of specific primer, 4 μl of termination mix, and distilled H2O to a final volume of 10 μl. Then, samples were subjected to 25 cycles at 96°C for10 seconds, 50°C for 5 seconds, and 60°C for 4 minutes. Samples were then purified by ethanol and sodium acetate precipitation and run in an ABI310 instrument (PE-Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A subset of samples was sequenced in the Sequencing Facility of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center on an ABI377 instrument (PE-Applied Biosystems). Sequencing electropherograms were read at least twice.

Results and Discussion

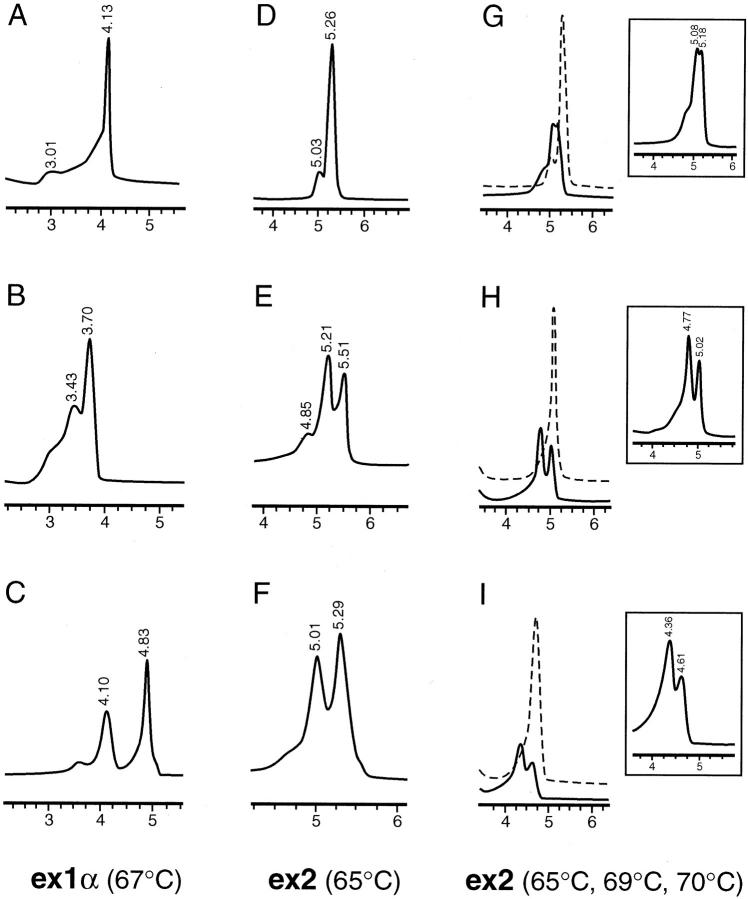

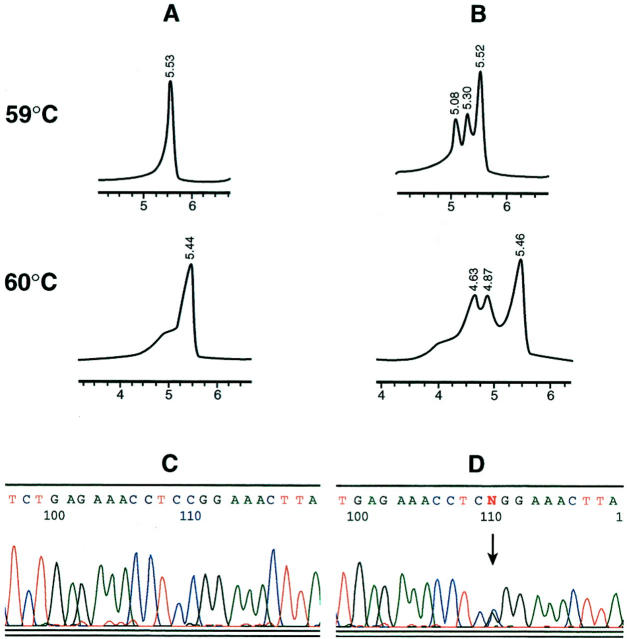

One hundred and twenty-nine DNA samples from melanoma subjects were analyzed for mutations or polymorphisms in exon 1α, 2, and 3 of the INK4A gene by both DHPLC and sequencing analyses. These samples corresponded to DNA from normal tissue (blood or buccal swab samples) from patients with primary melanoma. In addition, 13 known INK4A mutant or polymorphic DNA samples were available. A total of 42 amplicons showed a distinct non-wild-type profile, 29 corresponded to newly tested melanoma samples, and 13 to known mutants or variants that served as positive controls. Table 2summarizes the results obtained by DHPLC and sequencing for samples with sequence variations. Figure 1shows profiles corresponding to wild-type and mutant or variant DNA samples at different temperatures. The elution profiles for the normal control samples showed a single peak representative of wild-type homoduplex DNA (Figure 1A and Figure 2A ). The analysis of exon 2 revealed a small shoulder in heated and non-heated wild-type DNA control (Figure 1D) . This profile was reproduced in all runs at 65°C, and the DNA sequencing showed no changes. In contrast, each of the confirmed positive samples produced a profile with multiple peaks (Figure 1 , B–C, E–I; Figure 2B ). In some cases it was possible to differentiate between originally heterozygote and homozygote cases for a given mutation or polymorphism by the presence of an additional peak (data not shown). However, to distinguish hetero- from homozygote mutants, all positive samples were routinely re-analyzed without wild-type DNA in the tube. Two of the 129 amplicons corresponding to INK4A-ex1α showed a distinct positive pattern on DHPLC. When sequenced, these patterns corresponded to a single nucleotide change in c.32 (CTG/CCG; Leu → Pro) (sample no. 2021); and c.49 (ATC/ACC; Ile → Thr) (sample no. 2044; Figure 1C ). In view of the relatively low frequency of sequence variations present in our group of samples, we included 13 samples known to harbor INK4A mutations in different exons. Mutant controls F3, 1489F, and 1515F showed extra peaks in the chromatograms at diverse temperatures (Figure 1B ; Table 2 ). Among the INK4A-ex2 amplicons, 12 of 120 melanoma samples depicted positive profiles; these changes corresponding to the following mutations and/or polymorphisms: one case at c.53 (ATG/ATC; Met → Ile); two cases at c.101 (GGG/TGG; Gly → Trp); one case at c.106 (GTG/GTA; Val → Val); and eight cases at c.148 (GCG/ACG; Ala → Thr). Mutant control samples showed extra peaks and/or change of the profile at the expected temperatures based on the predicted melting profile (1452F, 250F, 114F 1515F, BlTm50, BlTm60, and BlTm105; Table 2 , and Figure 1 ). Control 338F showed the same change (Met53Ile) as sample 2028 (Table 2) ; control 553F contained the same change (Ala148Thr) as sample 2049 (depicted in Figure 1E ). In a few cases, samples showed a distinct non-wild-type pattern on DHPLC at the three temperatures tested, as depicted for SK-Mel21 (Table 2 ; Figure 1 , G-I). Fifteen of 59 INK4A-ex3 amplicons showed positive patterns on the chromatogram and sequencing analyses revealed presence of variations in the position 500 (G/C) (Figure 2) . Variant controls 1620F (nucleotide 500 C/G) and 948F (nucleotide 500 C/G and 540 C/G) were positive, and the chromatographic profile looked identical. This is due to the fact that although the control 948F has an additional nucleotide change, this is located 5′ from the reverse primer, and therefore, cannot be detected.

Figure 1.

Detection of INK4A mutations by DHPLC. Elution profiles obtained in melanoma cases or known mutants for INK4A exon 1α at 67°C (A, B, C); INK4A exon 2 at 65°C (D, E, F); and INK4A exon 2 at 65, 69, and 70°C (G, H, I). Representative normal profiles are depicted in panels A and D. Note the additional peaks obtained for the mutant control no. 1489F, case no. 2044, case no. 2049 and control BlTm50 (panels B, C, E, F; Table 2 ). The mutation present in cell line SK-Mel21 (c.58 Arg → stop) is evident at all of the temperatures analyzed for exon 2, as compared with a wild-type elution profile (dotted line) (G, H, I, note details of the mutant profile). The numbers on the x axis correspond to the column retention time in minutes. Only a portion of the chromatographic profile containing the homoduplex or heteroduplex peaks is shown.

Figure 2.

Detection of INK4A-exon 3 variants by DHPLC and direct sequencing. A: Homoduplex profile in normal human placental DNA obtained at 59°C (upper panel) and 60°C (middle panel). B: Heteroduplex profile corresponding to melanoma DNA no. 2046 mixed with wild-type DNA. C: Sequencing analysis of normal DNA showing the C/C variant in position 500. D: Sequencing analysis of case no. 2046 shows heterozygosity (C/G, arrow) at position 500.

Table 2.

INK4A Mutation Detection by Denaturing HPLC and Sequencing-Selected Cases

| Amplicon | Sample ID | DHPLC* | Sequencing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp1 | Temp2 | Temp3 | |||

| Exon 1α | 1489F | (+) | (+) | (+/−) | Arg24Pro |

| 2021† | wt | (+) | (+) | Leu32Pro | |

| 2044 | (+) | (+) | (+) | Ile49Thr | |

| F3 | (+) | (+) | (+/−) | Gln50Arg | |

| 1515F | (+) | (+) | (+) | 88delG | |

| Exon 2 | B1Tm50 | (+) | wt | wt | A → T nt.(−2) exon 2† |

| 2028 | (+) | wt | wt | Met53Ile | |

| 1452F | (+) | (+) | (+) | Met53Thr; Asp108Asn | |

| 250F | wt | (+) | (+) | Pro81Leu | |

| 114F | wt | (+) | (+/−) | Asp84Ala | |

| B1Tm60 | (+) | wt | wt | c.80 Arg → stop | |

| 2047 | wt | (+) | (+) | Gly101Trp | |

| 1109† | (+) | (+) | (+) | Val106Val; Ala148Thr | |

| 1080 | (+)-Hom | wt | wt | Ala148Thr (Hom) | |

| 2049 | (+) | wt | wt | Ala148Thr | |

| 2021† | (+) | wt | wt | Ala148Thr | |

| SK-Mel21 | (+) | (+) | (+) | c.58 Arg → stop | |

| Exon 3 | 1052 | (+) | (+) | — | nt.500 g/g Hom‡ |

| 2046 | (+) | (+) | — | nt.500 c/g het‡ | |

| 948F† | (+) | (+) | — | nt.500 c/g het‡ | |

Temp1: 67°C (exon 1 α), 65°C (exon 2), or 59°C (exon 3). Temp2: 69°C (exons 1α and 2) or 60°C (exon 3). Temp3: 70°C (exons 1α and 2).

Wt, wild type;

denotes samples with more than one nucleotide change. (+), aberrant or positive profile. Hom: homozygote; het, heterozygote.

The location of the nucleotide change takes into account the 24 nucleotides added to the original report of Serrano et al, 7 corresponding the position 500 to the 26th nucleotide after the stop codon.

All positive cases were reanalyzed by running them without the mix of amplified wild-type DNA. Most of the samples were heterozygous for the mutation detected. Samples containing mutations or polymorphisms were detected at different temperatures according to the position of the nucleotide change. This is due to the fact that the GC% varies throughout the INK4A sequence and the melting profile is not uniform. As an example, based on the GC content of the surrounding sequence, the common polymorphism in c.148 cannot be detected at 70°C or 69°C because most of the DNA strands are completely denatured, and the DHPLC detection is based on the different retention times of partially denatured DNA. Specifically, it is desirable to analyze samples when the majority of the strands are partially annealed.

Almost all of the alterations observed at 65°C corresponded to the common polymorphism in codon 148 (Ala → Thr), yet in one case the shape of the extra peak differed slightly and this heteroduplex corresponded to a sample carrying an additional nucleotide change in codon 106 (case no. 1109, Table 2 ). In addition, this second nucleotide change was evident at 69°C and 70°C; this fact emphasizing the consequence of the temperature choice for this assay. In a few cases, a single mutation was identified at multiple temperatures (Figure 1G 1H 1I , and details).

It is of fundamental importance to efficiently and accurately detect gene sequence variations within DNA samples. When analyzing point mutations, the standard method of choice is direct DNA sequencing, but other time and cost-effective methods have been implemented for the initial screening by us and many other investigators. One of such methods, the PCR-SSCP, is indeed faster, sensitive, and less expensive then sequencing. However, several conditions need to be tried to achieve the desired sensitivity (acrylamide %; glycerol %; temperature, etc). 21 In addition, gels need to be exposed to a sensitive film for a variable length of time, and the interpretation of band patterns can be cumbersome for the inexperienced eye. Denaturing HPLC has been successfully applied in the mutation detection of BRCA1 gene, 27, 28, 29 PTEN, 30, 31 and the tuberous sclerosis genes TSC1 and TSC2. 24, 32 It has been estimated that the sensitivity of the detection is greater than 95%; 30 similar or superior to that obtained by SSCP. 24, 30, 33, 34 The sensitivity of the method is dependent on the temperature at which the analysis is completed, and to partially circumvent the operator’s experience, software has been developed for predicting the optimal temperature for DHPLC analysis. For the analyses of INK4A mutations we have relied on the software-based predictions and we also selected overlapping temperatures to increase the chance of heteroduplex detection. Under the conditions used in the present study, DHPLC detected 100% of the mutations detected by sequencing. No nucleotide variation was detected by sequencing in cases lacking additional peaks or for cases in which the slope of the curve differed slightly (n = 16 amplicons) from that obtained for the wild-type DNA. This fact does not mean that the method is underestimating alterations, but confirms that, as with any quick screening method, positive results need to be further characterized by sequencing. Although we have not detected any false negative or false positive cases, it is advisable to sequence a small percentage of randomly selected samples as a standard procedure for quality control purposes. As with any other mutation detection method, including sequencing, DHPLC has its limitations. 35, 36 It is possible that a mutation located at the very end of the fragment would be undetected. To overcome this possibility, primers should be located outside the area of interest. We have successfully identified 16 different mutations spanning exons 1α, 2, and 3, and we will be verifying the sensitivity of the method by including additional known mutant DNA samples as they become available.

Results from our present study demonstrate that within the oligonucleotide sets, buffer gradient, and temperature conditions chosen for the screening of INK4A/p16 mutations, DHPLC is a very sensitive, reliable, fast and reproducible semi-automated method. One sample can be processed in 12 minutes with an estimated cost of approximately one-tenth of automated sequencing. Both the DHPLC and the automated sequencer are of similar cost and while not every laboratory can afford to acquire these instruments, the cost and labor involved in the sample preparation favor the DHPLC. As an example, the approximate cost for sequencing a PCR fragment in both directions is $20 to $24, while the analyses of an amplicon by DHPLC at three different temperatures is estimated in $1.35 to $1.45. As an additional advantage, it does not require radioactive or fluorescent labeling, and samples could be stored in the freezer for a long time before being processed. Nevertheless, it is crucial to establish adequate protocols and to conduct validation studies with as many known mutants as possible for each newly designed fragment or target, regardless of the gene of interest. As with any screening system, every positive or nearly-positive sample should be verified by a standard method.

In conclusion, denaturing DHPLC is a very useful screening method for the detection of INK4A gene alterations, whether the analysis targets sporadic mutations in tumor DNA, or germline mutations in blood or buccal cells. Particularly in our ongoing epidemiological study, it will be a very valuable tool for the evaluation of the interaction between the INK4A gene and environment, as it will permit a faster assessment of INK4A mutations and polymorphisms in large cohort of cases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Houghton, G. Walker, M. Harland, and J. Newton-Bishop for providing us with mutant DNA samples; Dr. D. Polsky for providing us with DNA from keratinocytes and critical suggestions; M. Akram and S. Eng for skillful help with DNA extraction; and Drs. E. Hernando-Monge and F. Bonilla for useful comments on the manuscript.

Address reprint requests to Marianne Berwick, Ph.D., M.P.H., Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, Room S-737, New York, New York 10021. E-mail: berwickm@mskcc.org.

Footnotes

Supported by the Byrne Fund Award, the Schultz Foundation, and NCI U01CA83180.

References

- 1.Rigel DS, Carucci JA: Malignant melanoma: prevention, early detection, and treatment in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin 2000, 50:215–236; 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Cohn-Cedermark G, Mansson-Brahme E, Rutqvist LE, Larsson O, Johansson H, Ringborg U: Trends in mortality from malignant melanoma in Sweden, 1970–1996. Cancer 2000, 89:348-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hara H, Walsh N, Yamada K, Jimbow K: High plasma level of a eumelanin precursor, 6-hydroxy-5-methoxyindole-2-carboxylic acid, as a prognostic marker for malignant melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 1994, 102:501-505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiFronzo LA, Wanek LA, Elashoff R, Morton DL: Increased incidence of second primary melanoma in patients with a previous cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 1999, 6:705-711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serraino D, Fratino L, Gianni W, Campisi C, Pietropaolo M, Trimarco G, Marigliano V: Epidemiological aspects of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Oncol Rep 1998, 5:905-909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacKie RM: Incidence, risk factors and prevention of melanoma. Eur J Cancer 1998, 34 (Suppl 3):S3-S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D: A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclinD/CDK4. Nature 1993, 366:704-707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamb A, Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Liu Q, Harshman K, Tavtigian SV, Stockert E, Day RS, III, Johnson BE, Skolnick MH: A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science 1994, 264:436-440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nobori T, Miura K, Wu DJ, Lois A, Takabayashi K, Carson DA: Deletions of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 inhibitor gene in multiple human cancers. Nature 1994, 368:753-756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori T, Miura K, Aoki T, Nishihira T, Mori S, Nakamura Y: Frequent somatic mutation of the MTS1/CDK4I (multiple tumor suppressor/cyclin-dependent kinase 4 inhibitor) gene in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 1994, 54:3396-3397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X, Tarmin L, Yin J, Jiang HY, Suzuki H, Rhyu MG, Abraham JM, Meltzer SJ: The MTS1 gene is frequently mutated in primary human esophageal tumors. Oncogene 1994, 9:3737-3741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Liu Q, Frye C, Eeles R, Orlow I, Lacombe L, Ponce-Castaneda V, Lianes P, Latres E, Skolnik M, Cordon-Cardo C, Kamb A: Genetic evidence in melanoma and bladder cancers that p16 and p53 function in separate pathways of tumor suppression. Am J Pathol 1995, 146:1199-1206 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman JG, Merlo A, Mao L, Lapidus RG, Issa JP, Davidson NE, Sidransky D, Baylin SB: Inactivation of the CDKN2/p16/MTS1 gene is frequently associated with aberrant DNA methylation in all common human cancers. Cancer Res 1995, 55:4525-4530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merlo A, Herman JG, Mao L, Lee DJ, Gabrielson E, Burger PC, Baylin SB, Sidransky D: 5′ CpG island methylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the tumor suppressor p16/CDKN2/MTS1 in human cancers. Nat Med 1995, 1:686-692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlow I, Lacombe L, Hannon GJ, Serrano M, Pellicer I, Dalbagni G, Reuter VE, Zhang ZF, Beach D, Cordon-Cardo C: Deletion of the p16 and p15 genes in human bladder tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:1524-1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orlow I, LaRue H, Osman I, Lacombe L, Moore L, Rabbani F, Meyer F, Fradet Y, Cordon-Cardo C: Deletions of the INK4A gene in superficial bladder tumors: association with recurrence. Am J Pathol 1999, 155:105-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monzon J, Liu L, Brill H, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, From L, McLaughlin J, Hogg D, Lassam NJ: CDKN2A mutations in multiple primary melanomas. N Engl J Med 1998, 338:879-887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussussian CJ, Struewing JP, Goldstein AM, Higgins PA, Ally DS, Sheahan MD, Clark WHJ, Tucker MA, Dracopoli NC: Germline p16 mutations in familial melanoma. Nat Genet 1994, 1994:8:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Aitken J, Welch J, Duffy D, Milligan A, Green A, Martin N, Hayward N: CDKN2A variants in a population-based sample of Queensland families with melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999, 91:446-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haluska FG, Hodi FS: Molecular genetics of familial cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1998, 16:670-682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orita M, Suzuki Y, Sekiya T, Hayashi K: Rapid and sensitive detection of point mutations and DNA polymorphisms using the polymerase chain reaction. Genomics 1989, 5:874-879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Underhill PA, Jin L, Zemans R, Oefner PJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL: A pre-Columbian Y chromosome-specific transition and its implications for human evolutionary history. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:196-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oefner PJ: Allelic discrimination by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 2000, 739:345-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choy YS, Dabora SL, Hall F, Ramesh V, Niida Y, Franz D, Kasprzyk-Obara J, Reeve MP, Kwiatkowski DJ: Superiority of denaturing high performance liquid chromatography over single-stranded conformation and conformation-sensitive gel electrophoresis for mutation detection in TSC2. Ann Hum Genet 1999, 63:383-391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harland M, Meloni R, Gruis N, Pinney E, Brookes S, Spurr NK, Frischauf A-M, Bataille V, Peters G, Cuzick J, Selby P, Bishop DT, Newton Bishop JA: Germline mutations of the CDKN2 gene in UK melanoma families. Hum Mol Genet 1997, 6:2061–2067 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Rees WA, Yager TD, Korte J, von Hippel PH: Betaine can eliminate the base pair composition dependence of DNA melting. Biochemistry 1993, 32:137-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold N, Gross E, Schwarz-Boeger U, Pfisterer J, Jonat W, Kiechle M: A highly sensitive, fast, and economical technique for mutation analysis in hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. Hum Mutat 1999, 14:333-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner T, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Fleischmann E, Muhr D, Pages S, Sandberg T, Caux V, Moeslinger R, Langbauer G, Borg A, Oefner P: Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography detects reliably BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Genomics 1999, 62:369-376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner TM, Moslinger RA, Muhr D, Langbauer G, Hirtenlehner K, Concin H, Doeller W, Haid A, Lang AH, Mayer P, Ropp E, Kubista E, Amirimani B, Helbich T, Becherer A, Scheiner O, Breiteneder H, Borg A, Devilee P, Oefner P, Zielinski C: BRCA1-related breast cancer in Austrian breast and ovarian cancer families: specific BRCA1 mutations and pathological characteristics. Int J Cancer 1998, 77:354-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu W, Smith DI, Rechtzigel KJ, Thibodeau SN, James CD: Denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) used in the detection of germline and somatic mutations. Nucleic Acids Res 1998, 26:1396-1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yokomizo A, Tindall DJ, Drabkin H, Gemmill R, Franklin W, Yang P, Sugio K, Smith DI, Liu W: PTEN/MMAC1 mutations identified in small cell, but not in non-small cell lung cancers. Oncogene 1998, 17:475-479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones AC, Austin J, Hansen N, Hoogendoorn B, Oefner PJ, Cheadle JP, O’Donovan MC: Optimal temperature selection for mutation detection by denaturing HPLC and comparison to single-stranded conformation polymorphism and heteroduplex analysis. Clin Chem 1999, 45:1133-1140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross E, Arnold N, Goette J, Schwarz-Boeger U, Kiechle M: A comparison of BRCA1 mutation analysis by direct sequencing, SSCP and DHPLC. Hum Genet 1999, 105:72-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis LA, Taylor CF, Taylor GR: A comparison of fluorescent SSCP and denaturing HPLC for high throughput mutation scanning. Hum Mutat 2000, 15:556-564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humma LM, Farmerie WG, Wallace MR, Johnson JA: Sequencing of B2-adreno-ceptor gene PCR products using Taq BigDyeTM terminator chemistry results in inaccurate base calling. Biotechniques 2000, 29:962-970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naeve CW, Buck GA, Niece RL, Pon RT, Robertson M, Smith AJ: Accuracy of automated DNA sequencing: a multi-laboratory comparison of sequencing results. Biotechniques 1995, 19:448–453 [PubMed]