Abstract

The effects of three metabolic inhibitors (acetylene, methanol, and allylthiourea [ATU]) on the pathways of N2 production were investigated by using short anoxic incubations of marine sediment with a 15N isotope technique. Acetylene inhibited ammonium oxidation through the anammox pathway as the oxidation rate decreased exponentially with increasing acetylene concentration; the rate decay constant was 0.10 ± 0.02 μM−1, and there was 95% inhibition at ∼30 μM. Nitrous oxide reduction, the final step of denitrification, was not sensitive to acetylene concentrations below 10 μM. However, nitrous oxide reduction was inhibited by higher concentrations, and the sensitivity was approximately one-half the sensitivity of anammox (decay constant, 0.049 ± 0.004 μM−1; 95% inhibition at ∼70 μM). Methanol specifically inhibited anammox with a decay constant of 0.79 ± 0.12 mM−1, and thus 3 to 4 mM methanol was required for nearly complete inhibition. This level of methanol stimulated denitrification by ∼50%. ATU did not have marked effects on the rates of anammox and denitrification. The profile of inhibitor effects on anammox agreed with the results of studies of the process in wastewater bioreactors, which confirmed the similarity between the anammox bacteria in bioreactors and natural environments. Acetylene and methanol can be used to separate anammox and denitrification, but the effects of these compounds on nitrification limits their use in studies of these processes in systems where nitrification is an important source of nitrate. The observed differential effects of acetylene and methanol on anammox and denitrification support our current understanding of the two main pathways of N2 production in marine sediments and the use of 15N isotope methods for their quantification.

In recent years, our understanding of the nitrogen cycle has been amended with several new pathways, including anaerobic ammonium oxidation and anaerobic methane oxidation coupled to denitrification (8, 18, 28). Among these pathways, the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium with nitrite (known as the anammox process) has the most well-documented importance for nitrogen cycling in marine environments (8, 28). Thus, Devol argued that globally anammox may be responsible for up to 50% of the total marine N2 production (9), which has previously been attributed entirely to denitrification (56). Moreover, recent studies of the oxygen-deficient zones off Namibia and Chile have indicated that anammox could be responsible for an even larger part of the nitrogen loss from the oceans (29, 51).

In marine sediments, anammox has been reported to account for up to 80% of the N2 production based on incubation experiments with 15N-labeled nitrogen species, and the remainder was produced by denitrification (8). The factors controlling the importance of the anammox process are still poorly understood. However, it appears that greater contributions occur in sediments with lower total carbon oxidation rates, implying that competition for nitrite with denitrifying bacteria is an important factor (8, 10, 50).

The power of using 15N-labeling experiments for quantification of anammox and denitrification rates lies in the unique labeling patterns which result from the distinct biochemistry of the two processes. Anammox bacteria oxidize ammonium to N2 by using nitrite as an electron acceptor in a 1:1 pair for the nitrogen atoms from the two sources (7, 50, 55), whereas denitrifying bacteria combine two molecules of nitrate to N2 in a stepwise pathway with free intermediates (2NO3− → 2NO2− → 2NO → N2O → N2) (60).

Inhibitors have been valuable experimental tools for studies of the activities and functions of various benthic microbial processes, including nitrification and denitrification (17, 26, 34, 45). Two inhibitors that have been used extensively in studies of the microbial nitrogen cycle are acetylene and allylthiourea (ATU) (13, 17, 26, 34, 45, 57). Acetylene at concentrations of 0.3 to 4 mM (0.7 to 10 kPa) inhibits the enzyme nitrous oxide reductase in the final step of denitrification (N2O → N2), and thus, the accumulation of nitrous oxide in samples with acetylene is used to determine denitrification rates (45, 46). Nitrification is even more sensitive to acetylene and is blocked by 4.1 μM (10 Pa) due to irreversible inhibition of ammonium monooxygenase in aerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (3, 4, 20). The differential sensitivity has been used experimentally to separate the two processes in sediment cores (43). ATU is another selective inhibitor of nitrification, blocking ammonium oxidation to nitrite at a concentration of 86 μM (3, 13). Recently, methanol has been suggested as a specific inhibitor of the anammox process based on studies performed with anammox enrichment cultures from wastewater, where methanol resulted in complete and irreversible loss of activity at concentrations of ≥0.5 mM (12). Specific inhibitors would be useful for direct determination of rates of anammox and denitrification, as well as nitrification, in intact sediment cores, where all these processes occur. Inhibitors would also be useful for testing other whole-core techniques which have recently been suggested but rely on several untested assumptions (36, 52). Moreover, the use of specific inhibitors could lead to a more detailed understanding of the relationship between anammox, denitrification, and nitrification.

In the present study we investigated the inhibitory effects of acetylene, methanol, and ATU on anammox and denitrification activities in marine sediments and the potential use of these inhibitors for studies of benthic nitrogen cycling. Experiments were performed with sediment from the deep Skagerrak and Gullmarsfjorden, two locations where the contributions of anammox have been well documented (7, 10, 50).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and sediment sampling.

The experiments in which acetylene and methanol were used as potential inhibitors of anammox were conducted with sediment samples obtained at a depth of 116 m in the deepest part of the Gullmarsfjord, which opens to Skagerrak on the Swedish west coast (station S3 in the study of Engström et al. [10]). Previous investigations have shown that the contribution of anammox to the total N2 production is 40% (10). Sediment samples were obtained in October 2004 using an Olausen box corer. The cores were transported to Denmark and were maintained at the in situ temperature (6°C) and in situ oxygen conditions by immersion in an air-purged reservoir containing bottom water from the Gullmarsfjord. The acetylene experiment and a pilot experiment with 0.11 mM methanol were performed when the samples were returned to the laboratory, while the methanol experiment was carried out 10 months later.

The study of the effect of ATU was performed in October 2000 with sediment collected using a box corer at station S9 at a depth of 695 m in the deep Skagerrak in connection with a series of experiments described by Dalsgaard and Thamdrup (7, 49, 50). At this location, the anammox process accounts for 67 to 79% of the N2 formation (7, 10, 50). Sediment cores were stored at the in situ temperature (6°C) until the start of the experiment 1 week after sampling.

Sediment handling and incubations.

The depth intervals used for incubations were 0 to 2, 1.5 to 2.5, and 1.3 to 3.8 cm in the acetylene, methanol, and ATU experiments, respectively. These intervals were chosen to represent the zone of nitrate consumption based on oxygen penetration depths of 2, 16, and 15 mm, as determined with an oxygen microsensor before each experiment (ox-100; Unisense) (49; P. Engström and N. Risgaard-Petersen, personal communication; M. M. Jensen, unpublished data). For all experiments, sediment samples from several cores were pooled and homogenized under N2 at the in situ temperature (10, 50). Sediments were incubated in Exetainer vials (12 ml; Labco) (30) with a helium headspace (acetylene and methanol experiments) or in completely filled glass centrifuge tubes (ATU experiment), as previously described (7), except that the sediment for the acetylene and methanol experiments was mixed 1:1 (vol/vol) with N2-purged 0.2-μm-filtered bottom water to obtain slurries.

In the acetylene and methanol experiments, He-purged stock solutions of inhibitors and 15N tracers were added with gas-tight glass syringes. Acetylene was added as acetylene-saturated water (∼40.7 mM), resulting in final concentrations of 0, 0.44, 1.3, 4.4, 8.8, 22, and 220 μM. Methanol was added to a final concentration of 0.11 mM in the pilot experiment and to final concentrations of 0.11, 0.33, 1.1, and 3.3 mM during the methanol experiment. Both compounds were injected 1 to 2 h before the 15N tracers were injected. Addition of 15N-labeled and unlabeled nitrogen compounds resulted in final concentrations of 100 μM for 15NH4+ and 50 to 100 μM for both unlabeled and labeled NO3− and 15NO2−. The resulting levels of 15N labeling of the nitrogen pools were 46 to 53% with 15NH4+, ≥98% with 15NO3−, and 98% with 15NO2− in the acetylene experiment and 77 to 79% with 15NH4+ and ≥99% with 15NO3− in the methanol experiment. The slurries were incubated in the dark. At different times, triplicate samples were terminated by injecting ZnCl2 (200 μl, 50% [wt/vol]) through the septa, and the ZnCl2 was carefully mixed with the slurries. The slurries were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min, and 4 ml of pore water was withdrawn through the septum of each vial while a 4-ml He headspace was introduced. Pore water was filtered through prerinsed 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate filters and frozen until dissolved inorganic nitrogen compounds were analyzed. The Exetainer vials were shaken and left upside down for later analysis of the isotopic composition of N2 and N2O.

In the experiment with ATU, homogenized sediment was divided into two equal portions. One of these portions received 50 μM 15NO3− plus 100 μM 14NH4+, while the other received 50 μM 15NO2− plus 100 μM 14NH4+. After homogenization, each of the preparations was divided into two ∼120-ml portions, one of which served as a control. The other portion received 12 ml of 9.75 mM ATU in seawater (final concentration of ATU in wet sediment, 886 μM). The sediment was loaded into 28-ml glass centrifuge tubes, which were capped with butyl rubber stoppers, leaving no headspace. Incubation and sampling were performed as previously described (7).

Analysis and stoichiometric calculations.

Nitrite contents were determined using the standard colorimetric method (16), whereas NOx− (NO3− plus NO2−) contents were determined by chemiluminescence after reduction to NO with acidic vanadium(III) chloride (5). Ammonium was quantified by flow injection analysis with conductivity detection (15). Water content and porosity were determined by using the dry and wet weights of known volumes of sediment. The isotopic composition and concentration of N2 were determined using an isotope ratio gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (Robo-Prep-G+ in line with TracerMass; Europa Scientific, Crewe, United Kingdom) by injecting headspace samples directly from the Exetainer vials (37).

Production of N2 by denitrification and anammox were calculated from the excess concentrations of 15N-labeled N2 (i.e., 29N2 and 30N2) and the 15N labeling of the NH4+, NO2−, or NO3− pools, respectively, by using the equations of Thamdrup et al. (49-51). The 15N labeling of NH4+, NO3−, and NO2− was calculated from the concentrations before and after addition of the tracer. The initial increase in the NH4+ concentration after addition of 15NH4+ corresponded to an estimated adsorption coefficient for NH4+ of 0.3 to 0.7. During incubation, unlabeled NH4+ is continuously produced by mineralization, which leads to dilution of the 15NH4+ added, thereby decreasing the degree of labeling of 15N. Since the total ammonium concentrations typically changed by ≤5% during the consumption of added NO3− and NO2−, the effect of 15N dilution should have been minor. This conclusion is supported by the similarity of the anammox rates obtained with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− and with 15NO3− (see below and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of rates of anammox and denitrification determined in control incubations and incubations with ATU

| Expt | Tracer(s) | Anammox (nmol N cm−3 h−1) | Denitrification (nmol N cm−3 h−1) | % Anammoxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylene | 15NH4+ + 14NO3− | 0.98 ± 0.03 | ||

| 15NO3− | 0.92 ± 0.1 | 6.13 ± 0.41 | 13 ± 0.7 | |

| 15NO2− | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 7.3 ± 0.95 | 10 ± 1.0 | |

| Methanol | 15NH4+ + 14NO3− | 2.75 ± 0.14 | ||

| 15NO3− | 2.46 ± 0.11 | 3.66 ± 0.45 | 38 ± 1.9 | |

| ATU | 15NO3− | 0.80 ± 0.005 | 0.74 ± 0.004 | 52 ± 0.1 |

| 15NO3− + 886 μM ATU | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | ||

| 15NO2− | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 52 ± 0.4 | |

| 15NO2− + 886 μM ATU | 0.62 ± 0.005 | 0.73 ± 0.008 |

The relative importance of anammox in total N2 production was derived from control incubations.

Volume-specific anammox and denitrification rates were calculated from the slopes of the linear regression lines for the concentrations of the nitrogen gas produced by each of the processes versus time (50, 51). The concentrations of nitrogen gas were corrected for the dilution resulting from the slurry incubations. Production of 15N-labeled N2 was considered significant when the slopes were significantly greater than zero, as evaluated by a one-tailed t test at the 5% level. As NO3− and NO2− typically were depleted at the third sampling during the experiments with acetylene and ATU, the rates of anammox and denitrification were calculated based on the first two samples obtained during the incubation. In the slurry incubations with methanol, the rates of the processes were calculated from linear regressions for five samplings during the 12 h of incubation. The contributions of anammox to the total N2 production were determined for the 15NO3− and 15NO2− incubations by determining the slopes of plots of the amounts of N2 produced by anammox versus the total N2 produced. This method of calculation allowed us to calculate a standard error for the estimates of the relative importance of anammox.

RESULTS

Acetylene and methanol experiments: general aspects.

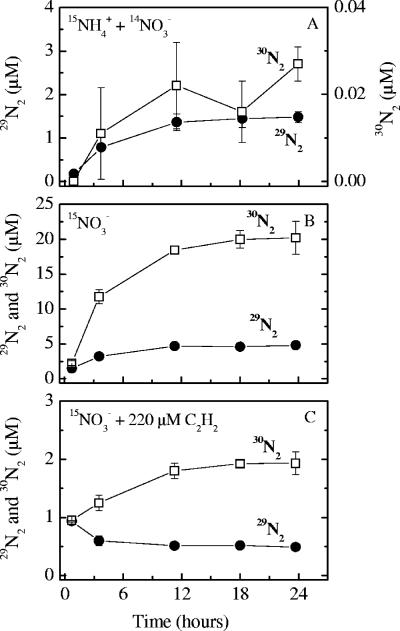

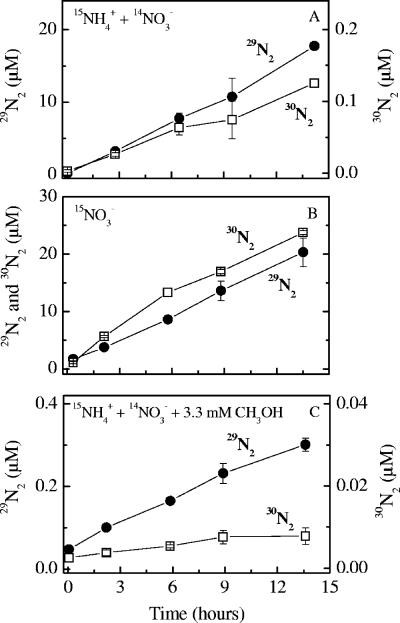

In the anoxic slurry incubations amended with only 15NH4+, there was no detectable production of 15N-labeled N2 with a molecular mass of either 29 or 30 (29N2 and 30N2) (data not shown). In incubations with 15NH4+ and unlabeled NO3− at acetylene concentrations of 0 to 22 μM, 15NH4+ was oxidized to 29N2 without delay, while there was no detectable production of 15N-labeled N2 at the highest acetylene concentration (220 μM) (Fig. 1). At acetylene concentrations of 0 to 1.3 and 8.8 μM, slight but significant production of 30N2 was observed during the 24 h of incubation, while no 30N2 production was detected at acetylene concentrations of 4.4, 22, and 220 μM (Fig. 1). However, the scattering of the 30N2 data did not permit precise determination of the rates of 30N2 production from 15NH4+ in any of these incubations. The higher degree of 15N labeling of the NH4+ pool in the methanol experiment increased the sensitivity compared to the acetylene experiment. Thus, with methanol significant accumulation of both 29N2 and 30N2 during the 12 h of incubation was observed in all the incubations with 15NH4+ plus unlabeled NO3− (Fig. 2A and C). The production of 30N2 accounted for less than 1% of the 29N2 production. As in previous experiments (7, 50, 55), the dominant production of 29N2 without delay indicated that anammox was the operating process, combining NH4+ with NO2− with a 1:1 stoichiometry.

FIG. 1.

Plots of concentrations of excess isotopically labeled N2 (29N2 and 30N2) versus time for slurry incubations with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− (A), 15NO3− (B), and 15NO3− plus 220 μM acetylene (C).

FIG. 2.

Plots of production of excess 29N2 and 30N2 versus time for slurry incubations with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− (A), 15NO3− (B), and 15NO3− plus 3.3 mM methanol (C).

In agreement with the results obtained with 15NH4+, the 15NO3− incubations showed that there was production of both 29N2 and 30N2 at acetylene concentrations of 0 to 8.8 μM, beginning immediately after addition of the tracer to the sediment slurries and continuing until the pool of NOx− was exhausted (Fig. 1B). As the initial 15N labeling of NO3− was greater than 98%, denitrification produced 30N2 almost exclusively in the incubations, whereas the production of 29N2 was mainly due to anammox bacteria using the 15NO2− formed by reduction of 15NO3− (7, 50). In the incubations with 22 and 220 μM acetylene, significant production of 30N2 from denitrification was observed, whereas the level of anammox activity was below the detection limit (Fig. 1C). Similarly, in the methanol experiment, production of 29N2 and 30N2 from 15NO3− was detected without delay (Fig. 2B). Since the degree of 15N labeling of nitrate in these incubations was greater then 99%, the production of 29N2 agrees with the results obtained for the incubations with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− and for the acetylene experiment, confirming the presence of anammox.

The control incubations without acetylene yielded similar rates of anammox and denitrification for the 15NO2− and 15NO3− treatments (Table 1). The contributions of anammox to the total N2 production were 10% ± 1.0% and 13% ± 0.7% in the incubations with 15NO2− and 15NO3−, respectively. In experiment with methanol, where anammox accounted for 38% ± 1.9% of the total N2 production, the control rates of anammox were approximately threefold higher, whereas the denitrification rate was approximately one-half of the rates observed in the acetylene experiment.

Effect of acetylene on rates of anammox and denitrification.

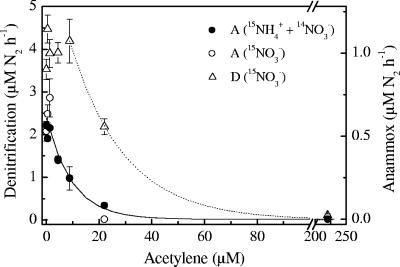

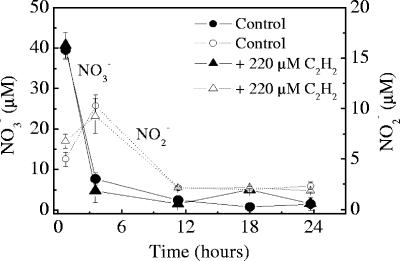

There was good agreement between the rates of anammox determined in incubations with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− and with 15NO3− (Fig. 3). The anammox rates decreased gradually with increasing acetylene concentrations, approaching zero asymptotically. The denitrification rates, determined by measuring 15N-labeled N2, were less sensitive to acetylene, as the rates started to decrease at higher acetylene concentrations (>8.8 μM). At a concentration of 22 μM, acetylene almost completely inhibited anammox activity, while the rate of N2 production by denitrification was still ∼60% of the control rate. The inhibition of 30N2 production from 15NO3− resulted in a corresponding accumulation of double-labeled N2O (15N15NO), demonstrating that acetylene inhibited the activity of nitrous oxide reductase in denitrifying bacteria (data not shown). The bulk concentrations of oxidized inorganic nitrogen species (NO2− and NO3−) exhibited the same trends regardless of the acetylene level, showing a transient accumulation of NO2− during NO3− consumption (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Rates of dinitrogen production by anammox and denitrification as a function of the concentration of acetylene. A and D indicate anammox and denitrification, respectively. The error bars indicate standard errors. The solid line represents the following function: anammox rate = 0.61 × e−0.10 × [acetylene]. The dotted line represents the following function: denitrification rate = 6.47 × e−0.049 × [acetylene].

FIG. 4.

Concentrations of NO3− and NO2− in control incubation and incubation with 220 μM acetylene. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The data are data for examples of incubations amended with 15NO3−. The same trends were observed in incubations with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3−.

The rates of N2 production were empirically fitted to an exponential decay function:

|

(1) |

where R(C) is the rate of anammox or denitrification at the inhibitor concentration (C), R0 is the uninhibited process rate, and k is the decay or suppression constant. Nonlinear least-squares curve fits using the Leventhal-Marquardt algorithm (32) (Fig. 3) yielded k = 0.10 ± 0.02 μM−1 and k = 0.049 ± 0.004 μM−1 for anammox and denitrification, respectively. Thus, anammox was approximately twice as sensitive to acetylene as denitrification.

Effect of methanol on rates of anammox and denitrification.

Similar to the results of the acetylene experiment, there was good agreement between anammox rates determined in incubations with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− and with 15NO3− (Fig. 5). The anammox rates decreased steadily with higher methanol concentrations until the concentration was 3.3 mM, which caused a 98% reduction in the anammox rate (incubation with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3−). Equation 1 again provided a good fit with a decay constant of 0.79 ± 0.12 mM−1 (Fig. 5). Addition of 3.3 mM methanol resulted in an increase in the denitrification rate of almost 50% compared to the control rate, and the data were consistent with a linear response where R(C) = 0.33C + 2.04 (R2 = 0.99) (Fig. 5). Besides the decrease in anammox rates, higher methanol levels also resulted in a continuous decrease in the rate of 30N2 production (data not shown), while the ratio of 30N2 production to 29N2 production of 0.7% at 0 to 1.1 mM methanol increased to 2.2% at 3.3 mM methanol. For the production of 30N2, equation 1 provided a good fit with a decay constant of 0.70 ± 0.14 mM−1 (data not shown), similar to the decay constant for anammox.

FIG. 5.

Anammox and denitrification rates as a function of the methanol concentration. A and D indicate anammox and denitrification, respectively. The error bars indicate standard errors. The solid line represents the following function: anammox rate = 1.40 × e−0.79 × [methanol]. The dashed line represents the following linear function: denitrification rate = 0.33C + 2.04 (R2 = 0.99).

Methanol at a concentration of 0.11 mM was added twice to incubation series with 15NO3− and with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3−, both as a small pilot experiment during the acetylene experiment and later during the methanol experiment. Addition of 0.11 mM methanol resulted in the same level of inhibition of anammox in both experiments, decreasing the rate by 22% and 18% compared to controls, whereas the denitrification rates were not affected when only control and 0.11 mM experiments were compared (P > 0.05, as determined by two-tailed t tests) (data not shown). Thus, methanol had the same influence on anammox and denitrification in the range of activities observed (Table 1).

The dynamics of NH4+ and NO2− differed significantly among the methanol treatments (Fig. 6). At methanol concentrations of 0 to 0.33 mM, both the NH4+ and NO2− concentrations decreased over time, and the average rates were 0.38 and 0.09 μM h−1 for NH4+ and NO2−, respectively. At 1.1 mM methanol, which is close to the concentration at which the anammox rate was one-half of the control level, the concentrations of NH4+ and NO2− remained constant. Conversely, an increase in the concentration of NO2− was observed during incubation with 3.3 mM methanol, while there was no significant change in the NH4+ concentration (P > 0.05, as determined by a one-tailed t test).

FIG. 6.

Net increases and decreases in NO2− and NH4+ concentrations as a function of the methanol concentration. Rates were calculated from the slopes of linear regression lines of the concentrations of NO2− and NH4+ versus time in incubations amended with 15NO3−. The decreases and increases in nutrient concentrations over time are indicated by negative and positive rates, respectively. The error bars indicate standard errors.

ATU experiment.

The ATU experiment was carried out in combination with several other experiments to investigate the factors that control anammox (7). Dalsgaard and Thamdrup (7) interpreted the accumulation of 29N2 in anoxic sediment incubations with 15NH4+ and unlabeled NO3− or NO2− and the slight production of 30N2 from 15NH4+ as evidence of anammox activity (50). Similar to our other experiments, production of 29N2 and 30N2 was observed immediately after the addition of 15NO3− and 15NO2−, with the concentrations increasing linearly over time until NOx− was consumed. In the control incubations, the rates of both anammox and denitrification were similar in the 15NO3− and 15NO2− incubations (P > 0.05, as determined by a two-tailed t test), and the relative importance of anammox in N2 production was 52% (Table 1). Addition of ATU resulted in slight but statistically significant inhibition of both denitrification and anammox (∼20% compared to the control in incubations with 15NO3−), while no detectable effect was observed with 15NO2− (P > 0.05, as determined by a two-tailed t test) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Acetylene.

Our data demonstrated that there was differential inhibition of anammox and denitrification by acetylene. Thus, a decrease in anammox activity was evident with 2 to 4 μM acetylene (∼5 to 9 Pa), while a measurable effect on N2O reduction in denitrifying bacteria required 10 μM acetylene (∼25 Pa) (Fig. 3). The higher sensitivity of anammox than of denitrification is illustrated by the twofold-higher decay constant (k = 0.10 ± 0.02 μM−1 for anammox and k = 0.049 ± 0.004 μM−1 for denitrification). Based on the curve fit, 95% inhibition of anammox was obtained with 29 μM acetylene (∼70 Pa), which also inhibited the N2O reduction in denitrifying bacteria by 63% (Fig. 3). Inhibition of anammox bacteria by acetylene has been demonstrated previously in batch cultures of anammox-enriched sludge, where anammox activity was inhibited by 6 mM acetylene (23, 53). The acetylene sensitivity of N2O reduction is consistent with previous observations for sediments, soil, and pure cultures, where complete inhibition of N2O reduction invariably occurred with ≥290 μM acetylene (≥0.7 kPa), while acetylene concentrations of ≤130 μM (≤0.3 kPa) resulted in only partial inhibition (1, 2, 44-46, 58, 59).

Nitrification is much more sensitive to acetylene than denitrification is (26, 27). The sensitive part is the first step in nitrification, as acetylene reacts irreversibly with ammonium monooxygenase at concentrations of ≥4.1 μM (∼10 Pa) in pure cultures and between ∼1 and 2 μM (∼2.5 and 5 Pa) in soils (3, 4, 20, 25). The previously reported inhibitory level used in intact sediment cores is 440 μM (∼1.0 kPa), which is well above levels for anammox inhibition (Fig. 3) (42, 43). Thus, the reported acetylene sensitivity of nitrification is similar to that of anammox. However, there are no indications that ammonium monooxygenase is involved in the anammox pathway (47), and anammox showed little sensitivity to ATU, another inhibitor of ammonium monooxygenase, which further supports the conclusion that acetylene must act on a different enzyme in the anammox pathway. Likewise, the absence of nitrous oxide reductase from anammox bacteria is indicated by the genome of “Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis” (47) and is consistent with the different sensitivities of anammox and denitrification to acetylene (Fig. 3). In the anammox pathway, acetylene appears to act on a third important enzyme in the microbial nitrogen cycle, and one of the suggested new components of the pathway is a likely candidate (47).

Methanol.

Our results demonstrate that methanol is also a potent specific inhibitor of the anammox process in marine sediments (Fig. 5). Opposite effects of methanol on anammox and denitrification were demonstrated by gradual suppression and stimulation of anammox and denitrification activity, respectively, with higher levels of methanol. The effect of methanol on the activity of anammox enrichment cultures from wastewater has been investigated by Güven and coworkers, who found that methanol at concentrations as low as 0.5 mM completely inhibited anammox activity (12). We found that marine anammox bacteria are only partially inhibited by this concentration, while nearly complete inhibition required 3.3 mM methanol (Fig. 5). However, the addition of an organic substrate at such high concentrations markedly stimulated denitrification, introducing an unwanted side effect. With respect to nitrification, an inhibitory effect of methanol has been found in activated sludge, where 15 mM methanol resulted in a 100% decrease in activity (24). According to Güven et al. (12), the mode of action of methanol may involve the conversion of methanol to formaldehyde by the enzyme hydroxylamine oxidoreductase found in both anammox bacteria and ammonium oxidizers (38).

In the incubation series with methanol and the associated control, a low but stable level of production of 30N2 from 15NH4+ was observed in the incubations amended with 15NH4+ plus 14NO3− (Fig. 2). The level of production of 30N2 was 2 orders of magnitude lower than the level of production of 29N2 in the control incubation. Production of 30N2 was not observed in the incubation amended with only 15NH4+, and the production decreased in parallel to the anammox activity with increasing methanol concentrations. A similar minor level of production of 30N2 from 15NH4+ has previously been reported for marine sediments where there was active anammox and, more importantly, for batch cultures with anammox bacteria from a wastewater bioreactor (48, 50, 54, 55). Thus, this production seems to be directly coupled to the anammox process rather than related to NH4+ oxidation by a different pathway involving, e.g., Mn oxide (19, 31). This conclusion was supported by the comparable decay constants for anammox (k = 0.79 ± 0.12 mM−1) and the production of 30N2 (k = 0.70 ± 0.14 mM−1). The simplest explanation for the 30N2 production seems to be related to the anammox pathway itself. During anammox, it is thought that NH4+ is converted to N2H4 through a reaction with NO catalyzed by the enzyme hydrazine hydrolase (47). If this step is reversible, 15N from the main product, 14N15NH4, could be transferred to the NO pool and from there return to react with 15NH4+ to form 15N15NH4 and 30N2. However, anammox bacteria appear to be metabolically versatile (12, 47), and the explanation for 30N2 production may also be found in other parts of their complex biochemistry.

ATU.

ATU had only minor effects on anammox and denitrification in incubations of sediment from Skagerrak (Table 1). Statistically significant reductions in both the anammox and denitrification rates were observed in the incubation amended with 15NO3−, while a similar effect on the processes was not observed for the 15NO2− incubations. Importantly, the effect of ATU with 15NO3− was minor (∼20% reduction compared to the control level), and both anammox and denitrification were affected to similar degrees (Table 1). ATU has been used in aquatic sediments for measurement of nitrification rates in mixed sediment and intact cores, as the inhibitor blocks efficiently at a concentration of 86 μM (13, 14), and ATU also inhibits nitrification in activated sludge (11). Cultured anammox bacteria exhibited no inhibition of activity by 0 to 10 mM ATU, in agreement with our results (23). As the concentration of ATU used in our incubations was approximately 10 times higher than the concentration reported for sediments, the range of concentrations at which nitrification is inhibited but there is little disruptive effect on anammox and denitrification in marine sediments is fairly large.

Interpretation and practical applications of the inhibitors.

Our finding that acetylene and methanol have different effects on anammox and denitrification illustrates that the two processes are decoupled. This supports our current understanding of the mechanisms involved in the removal of fixed nitrogen from marine sediments, as the production of N2 is connected to two distinct pathways, namely, anammox and denitrification. In addition, the decoupling between the two pathways implies that the N2 signals associated with anammox and denitrification can be separated, verifying the model for the isotope method devised by Thamdrup and Dalsgaard (50). Thus, as a practical matter it is possible in anoxic batch incubations to distinguish between the rates of N2 production from anammox and denitrification. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of acetylene on anammox activity implies that no hidden pools of native nitrate or nitrite were liberated during the sediment incubations with 15NO3−, as this would have resulted in 29N2 formation via denitrification, which was not detected (Fig. 1C). The overall effects of acetylene, methanol, and ATU correspond well with studies on the anammox process in wastewater bioreactors (12, 23, 53), which support the similarity between the marine anammox process and anammox bacteria in wastewater treatment plants and the natural realm (7, 22, 50).

Inhibitors are generally useful, albeit imperfect, tools for studies of microbial processes in natural systems (34). For studies of the role of anammox benthic nitrogen cycling, the ideal inhibitor would inhibit this process while leaving the other important processes unaffected. None of the compounds tested here fulfilled this criterion, and acetylene and methanol, which inhibited anammox, also affected both denitrification and the ammonium oxidation step of nitrification. The inhibition of nitrification limits the use of these inhibitors in many sediments where nitrification is the primary source of nitrate for denitrification and should also be the primary source of nitrite for anammox (21, 39). The accumulation of N2O in the presence of acetylene was previously used for quantification of denitrification in whole cores of marine sediment (43, 45), but the technique underestimates the rates when denitrification is coupled to nitrification (40). Still, our results suggest that this technique could be extended to separate anammox and denitrification in sediments where the bottom water is the main source of nitrate (e.g., in nitrate-rich estuaries and where the oxygen minimum zones impinge on the seafloor). In this case, the sum of anammox and denitrification could be determined as the total N2 flux from the unamended sediment (40), and denitrification could be quantified as N2O production at an appropriately high acetylene concentration (45), with anammox rates determined by determining the difference. Although this approach is probably less sensitive, it is also less demanding in terms of instrumentation than the proposed alternatives, which rely on nitrogen mass spectrometry (36, 50). A similar approach is relevant for batch incubations of anoxic water and sediment, where nitrification is absent (6, 50).

An important problem associated with determinations of anammox activity in whole-core incubations with 15NO3− is that when nitrification is active, the exact labeling of the pools of NO2− and NO3− at the site of their consumption is not known, and the production of 29N2 from anammox and denitrification cannot be separated (36). The ATU tolerance of anammox bacteria could help solve this problem. In sediment cores with inhibition of nitrification by ATU, the labeling of NO2− and NO3− in the sediment is the same as it is in the overlying water, where it can be accurately determined. In the same context, ATU may also be useful for testing a recently suggested whole-core technique, which uses the labeling of natural N2O in incubations with 15NO3− to determine the labeling of NO2−/NO3−, hence allowing separation of anammox and denitrification (52). One of the assumptions is that N2O is not produced by nitrification, which could be tested using ATU. Generally, the fact that anammox activity is not affected by ATU may prove to be useful in investigations of the coupling between anammox and nitrification in different systems. Coupling of these processes has been described in a wastewater reactor (33, 41) and has been suggested to be important in the Benguela upwelling system (29). Denitrification was not important in these cases, and the coupling of nitrification and anammox could therefore be examined directly with the help of ATU.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pia Engström and Stefan Hulth for the opportunity to sample sediment from the Gullmarsfjord. Pia Engström and the crew of the Swedish ship Oscar von Sydow are thanked for their enthusiasm and help with sampling. We gratefully acknowledge Lars Peter Nielsen for the use of his laboratory and mass spectrometer for measuring the N2 samples from the experiment with acetylene. Egon R. Frandsen is thanked for measuring the N2 samples from the methanol experiment.

This study was financially supported by the Danish National Research Foundation and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research (MISTRA).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, T. K., M. H. Jensen, and J. Sørensen. 1984. Diurnal variation of nitrogen cycling in coastal, marine sediments. I. Denitrification. Mar. Biol. 87:171-176. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balderston, W. L., B. Sherr, and W. J. Payne. 1976. Blockage by acetylene of nitrous oxide reduction in Pseudomonas perfectomarinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 31:504-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bédard, C., and R. Knowles. 1989. Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of CH4, NH4+, and CO oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol. Rev. 53:68-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg, P., L. Klemedtsson, and T. Rosswall. 1982. Inhibitory effect of low partial pressures of acetylene on nitrification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 14:301-303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braman, R. S., and S. A. Hendrix. 1989. Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium(III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chem. 61:2715-2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalsgaard, T., D. E. Canfield, J. Petersen, B. Thamdrup, and J. Acuna-Gonzalez. 2003. N2 production by the anammox reaction in the anoxic water column of Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica. Nature 422:606-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalsgaard, T., and B. Thamdrup. 2002. Factors controlling anaerobic ammonium oxidation with nitrite in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3802-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalsgaard, T., B. Thamdrup, and D. E. Canfield. 2005. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) in the marine environment. Res. Microbiol. 156:457-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devol, A. H. 2003. Solution to a marine mystery. Nature 422:575-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engström, P., T. Dalsgaard, S. Hulth, and R. C. Aller. 2005. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation by nitrite (anammox): implication for N2 production in coastal marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69:2057-2065. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginestet, P., J. Audic, V. Urbain, and J. Block. 1998. Estimation of nitrifying bacterial activities by measuring oxygen uptake in the presence of the metabolic inhibitors allylthiourea and azide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2266-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Güven, D., A. Dapena, B. Kartal, M. C. Schmid, B. Maas, K. van de Pas-Schoonen, S. Sozen, R. Mendez, H. J. M. Op den Camp, M. S. M. Jetten, M. Strous, and I. Schmidt. 2005. Propionate oxidation by and methanol inhibition of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1066-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, G. H. 1984. Measurement of nitrification rates in lake sediments: comparison of the nitrification inhibitors nitrapyrin and allylthiourea. Microb. Ecol. 10:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall, G. H., and C. Jeffries. 1984. The contribution of nitrification in the water column and profundal sediments to the total oxygen deficit of the hypolimmnion of a mesotrophic lake. Microb. Ecol. 10:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall, P. O. J., and R. C. Aller. 1992. Rapid small-volume flow injection analysis for ΣCO2 and NH4+ in marine and freshwaters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 37:1113-1119. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen, H. P., and F. Koroleff. 1999. Determination of nutrients, p. 159-223. In K. Grasshoff, K. Kremling, and M. Ehrhardt (ed.), Methods of seawater analysis. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 17.Henriksen, K., and W. M. Kemp. 1988. Nitrification in estuarine and coastal marine sediments, p. 207-249. In T. H. Blackburn and J. Sørensen (ed.), Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine environments, vol. 33. John Wiley and Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulth, S., R. C. Aller, D. E. Canfield, T. Dalsgaard, P. Engström, F. Gilbert, K. Sundbäck, and B. Thamdrup. 2005. Nitrogen removal in marine environments: recent findings and future research challenges. Mar. Chem. 94:125-145. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulth, S., R. C. Aller, and F. Gilbert. 1999. Coupled anoxic nitrification/manganese reduction in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63:49-66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hynes, R. K., and R. Knowles. 1982. Effect of acetylene on autotrophic and heterotrophic nitrification. Can. J. Microbiol. 28:334-340. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins, M. C., and W. M. Kemp. 1984. The coupling of nitrification and denitrification in two estuarine sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 29:609-619. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jetten, M. S. M., I. Cirpus, B. Kartal, L. van Niftrik, K. van de Pas-Schoonen, O. Sliekers, S. Haaijer, W. van der Star, M. Schmid, J. van de Vossenberg, I. Schmidt, H. Harhangi, M. van Loosdrecht, J. G. Kuenen, H. Op den Camp, and M. Strous. 2005. 1994-2004: 10 years of research on the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jetten, M. S. M., M. Strous, K. T. van de Pas-Schoonen, J. Schalk, U. van Dongen, A. A. van de Graaf, S. Logemann, G. Muyzer, M. C. M. van Loosdrecht, and J. G. Kuenen. 1998. The anaerobic oxidation of ammonium. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:421-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jõnsson, K., E. Apspichueta, A. de la Sota, and J. L. C. Jansen. 2001. Evaluation of nitrification-inhibition measurements. Water Sci. Technol. 43:201-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klemedtsson, L., J. M. Svensson, and T. Rosswall. 1988. A method of selective inhibition to distinguish between nitrification and denitrification as sources of nitrous oxide in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 6:112-119. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knowles, R. 1990. Acetylene inhibition technique: development, advantages and potential problems. FEMS Symp. 56:151-166. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knowles, R. 1985. Some effects on inhibitors on nitrogen transformations, p. 124-144. In K. A. Malik, S. H. M. Naqvi, and M. I. H. Aleem (ed.), Nitrogen and the environment. Nuclear Institute of Agriculture and Biology, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

- 28.Kuypers, M. M. M., G. Lavik, and B. Thamdrup. 2006. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation in the marine environment, p. 311-332. In L. N. Neretin (ed.), Past and present water column anoxia. NATO Sciences Series. IV. Earth and environmental sciences, vol. 64. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuypers, M. M. M., G. Lavik, D. Woebken, M. Schmid, B. M. Fuchs, R. Amann, B. B. Jørgensen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2005. Massive nitrogen loss from the Benguela upwelling system through anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:6478-6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laughlin, R. J., and R. J. Stevens. 2003. Changes in composition of nitrogen-15-labeled gases during storage in septum-capped vials. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 67:540-543. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luther, G. W., B. Sundby, B. L. Lewis, P. J. Brendel, and N. Silverberg. 1997. Interactions of manganese with the nitrogen cycle: alternative pathways to dinitrogen. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61:4043-4052. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marquardt, D. W. 1963. An algorithm for least-squares estimations of nonlinear parameters. J. Soc. Ind. Appl. Math. 11:431-441. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen, M., A. Bollmann, O. Sliekers, M. Jetten, S. M. M. Strous, I. Schmidt, L. Hauer Larsen, L. P. Nielsen, and N. P. Revsbech. 2005. Kinetics, diffusional limitation and microscale distribution of chemistry and organisms in a CANON reactor. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 51:247-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oremland, R. S., and D. G. Capone. 1988. Use of “specific” inhibitors in biogeochemistry and microbial ecology, vol. 10. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

- 35.Raghoebarsing, A. A., A. Pol, K. van de Pas-Schoonen, A. J. P. Smolders, K. F. Ettwig, I. C. Rijpstra, S. Schouten, J. S. Sinninghe Damsté, H. J. M. Op den Camp, M. S. M. Jetten, and M. Strous. 2006. A microbial consortium couples anaerobic methane oxidation to denitrification. Nature 440:918-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Risgaard-Petersen, N., L. P. Nielsen, S. Rysgaard, T. Dalsgaard, and R. L. Meyer. 2003. Application of the isotope pairing technique in sediments where anammox and denitrification coexist. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1:63-73. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risgaard-Petersen, N., and S. Rysgaard. 1995. Nitrate reduction in sediments and waterlogged soil measured by 15N techniques, p. 287-295. In K. Alef and P. Nannipieri (ed.), Methods in applied soil microbiology and biochemistry. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 38.Schalk, J., S. de Vries, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2000. Involvement of a novel hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Biochemistry 39:5405-5412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seitzinger, S. P. 1988. Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33:702-724. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seitzinger, S. P., L. P. Nielsen, J. Caffrey, and P. B. Christensen. 1993. Denitrification measurements in aquatic sediments: a comparison of three methods. Biogeochemistry 23:147-167. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sliekers, A. O., N. Derwort, J. L. C. Gomez, M. Strous, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. M. Jetten. 2002. Completely autotrophic nitrogen removal over nitrite in one single reactor. Water Res. 36:2475-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sloth, N. P., H. Blackburn, L. S. Hansen, N. Risgaard-Petersen, and B. A. Lomstein. 1995. Nitrogen cycling in sediments with different organic loading. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 116:163-170. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sloth, N. P., L. P. Nielsen, and T. H. Blackburn. 1992. Nitrification in sediment cores measured with acetylene inhibition. Limnol. Oceanogr. 37:1108-1112. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sørensen, J. 1978. Capacity for denitrification and reduction of nitrate to ammonia in a coastal marine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 35:301-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sørensen, J. 1978. Denitrification rates in a marine sediments as measured by the acetylene inhibition technique. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36:139-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sørensen, J., L. K. Rasmussen, and I. Koike. 1987. Micromolar sulfide concentrations alleviate acetylene blockage of nitrous oxide reduction by denitrifying Pseudomonas fluorescens. Can. J. Microbiol. 33:1001-1005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strous, M., E. Pelletier, S. Mangenot, T. Rattei, A. Lehner, M. W. Taylor, M. Horn, H. Daims, D. Bartol-Mavel, P. Wincker, V. Barbe, N. Fonknechten, D. Vallenet, B. Segurens, C. Schenowitz-Truong, C. Médigue, A. Collingro, B. Snel, B. E. Dutilh, H. J. M. Op den Camp, C. van der Drift, I. Cirpus, K. T. van de Pas-Schoonen, H. R. Harhangi, L. van Niftrik, M. Schmid, J. Keltjens, J. van de Vossenberg, B. Kartal, H. Meier, D. Frishman, M. A. Huynen, H. Mewes, J. Weissenbach, M. S. M. Jetten, M. Wagner, and D. Le Paslier. 2006. Deciphering the evolution and metabolism of an anammox bacterium from a community genome. Nature 440:790-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tal, Y., J. E. M. Watts, and H. J. Schreier. 2005. Anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and related activity in Baltimore Inner Harbor sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1816-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thamdrup, B., and T. Dalsgaard. 2000. The fate of ammonium in anoxic manganese oxide-rich marine sediment. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 64:4157-4164. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thamdrup, B., and T. Dalsgaard. 2002. Production of N2 through anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to nitrate reduction in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1312-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thamdrup, B., T. Dalsgaard, M. M. Jensen, O. Ulloa, L. Farias, and R. Escribano. 2006. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation in the oxygen-deficient waters off northern Chile. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51:2145-2156. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trimmer, M., N. Risgaard-Petersen, J. C. Nicholls, and P. Engstrom. 2006. Direct measurements of anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) and denitrification in intact sediment cores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 326:37-47. [Google Scholar]

- 53.van de Graaf, A. A., P. de Bruijn, L. A. Robertson, M. S. M. Jetten, and J. G. Kuenen. 1996. Autotrophic growth of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing micro-organisms in a fluidized bed reactor. Microbiology 142:2187-2196. [Google Scholar]

- 54.van de Graaf, A. A., P. de Bruijn, L. A. Robertson, M. S. M. Jetten, and J. G. Kuenen. 1997. Metabolic pathway of anaerobic ammonium oxidation on the basis of 15N studies in a fluidized bed reactor. Microbiology 143:2415-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van de Graaf, A. A., A. Mulder, P. de Bruijn, M. Jetten, L. A. Robertson, and G. Kuenen. 1995. Anaerobic oxidation of ammonium is a biologically mediated process. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1246-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ward, B. B. 2003. Significance of anaerobic ammonium oxidation in the ocean. Trends Microbiol. 11:408-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welsh, D. T., G. Castadelli, M. Bartoli, D. Poli, M. Careri, R. de Wit, and P. Viaroli. 2001. Denitrification in an intertidal seagrass meadow, a comparison of 15N-isotope and acetylene-block techniques: dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia as a source of N2O. Mar. Biol. 139:1029-1036. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshinari, T., R. Hynes, and R. Knowles. 1977. Acetylene inhibition of nitrous-oxide reduction and measurement of denitrification and nitrogen-fixation in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 9:177-183. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshinari, T., and R. Knowles. 1976. Acetylene inhibition of nitrous oxide reduction by denitrifying bacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 69:705-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zumft, W. G. 1997. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:533-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]