Abstract

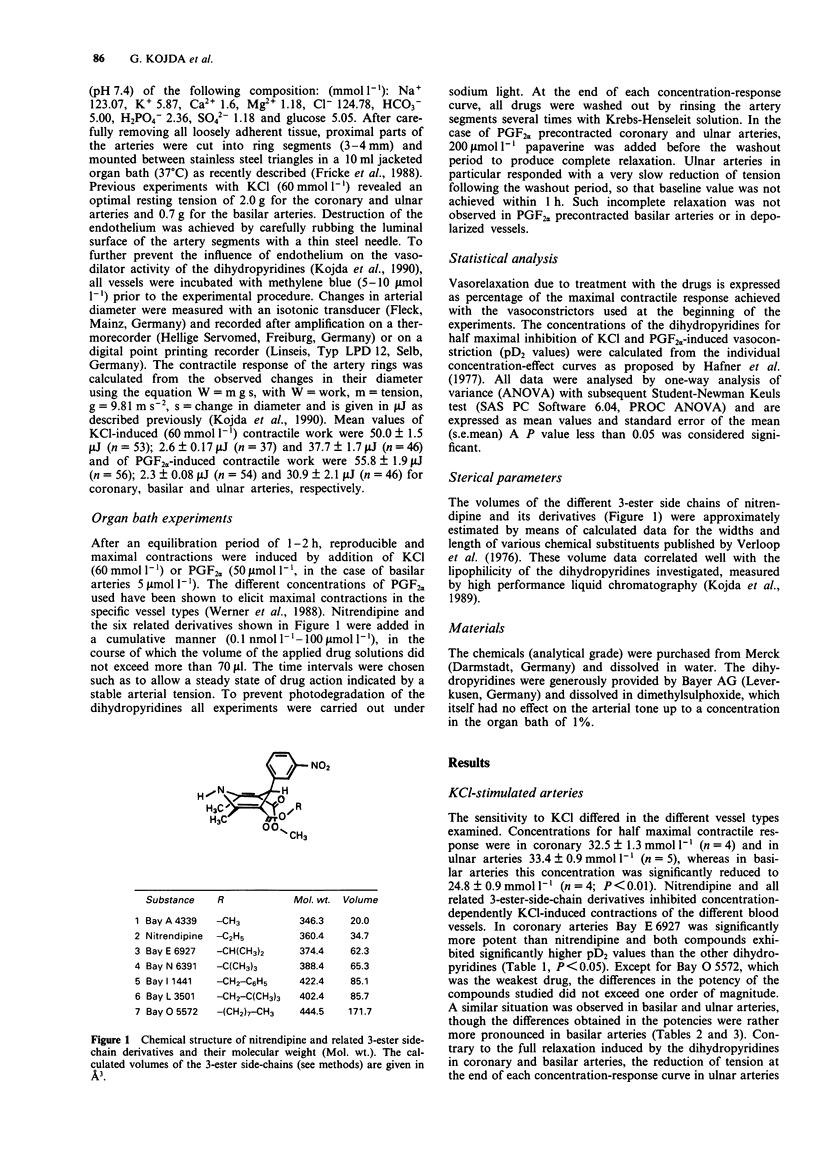

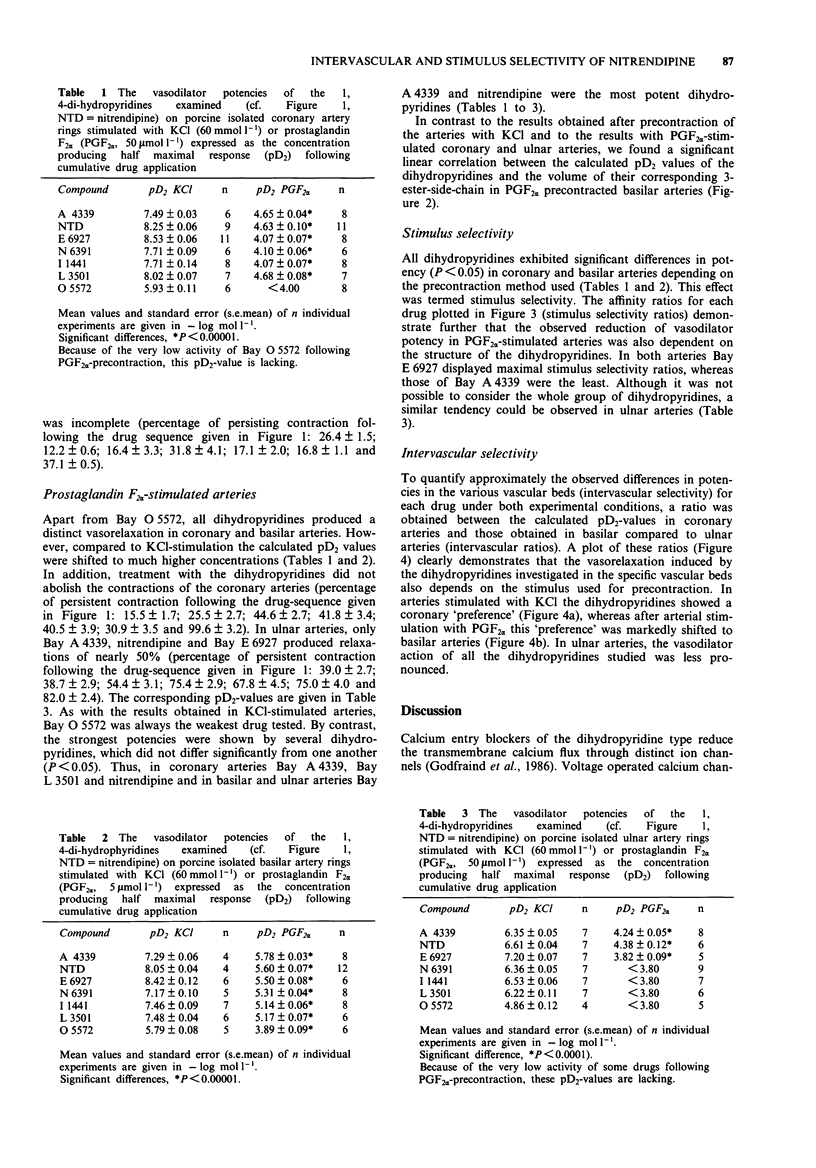

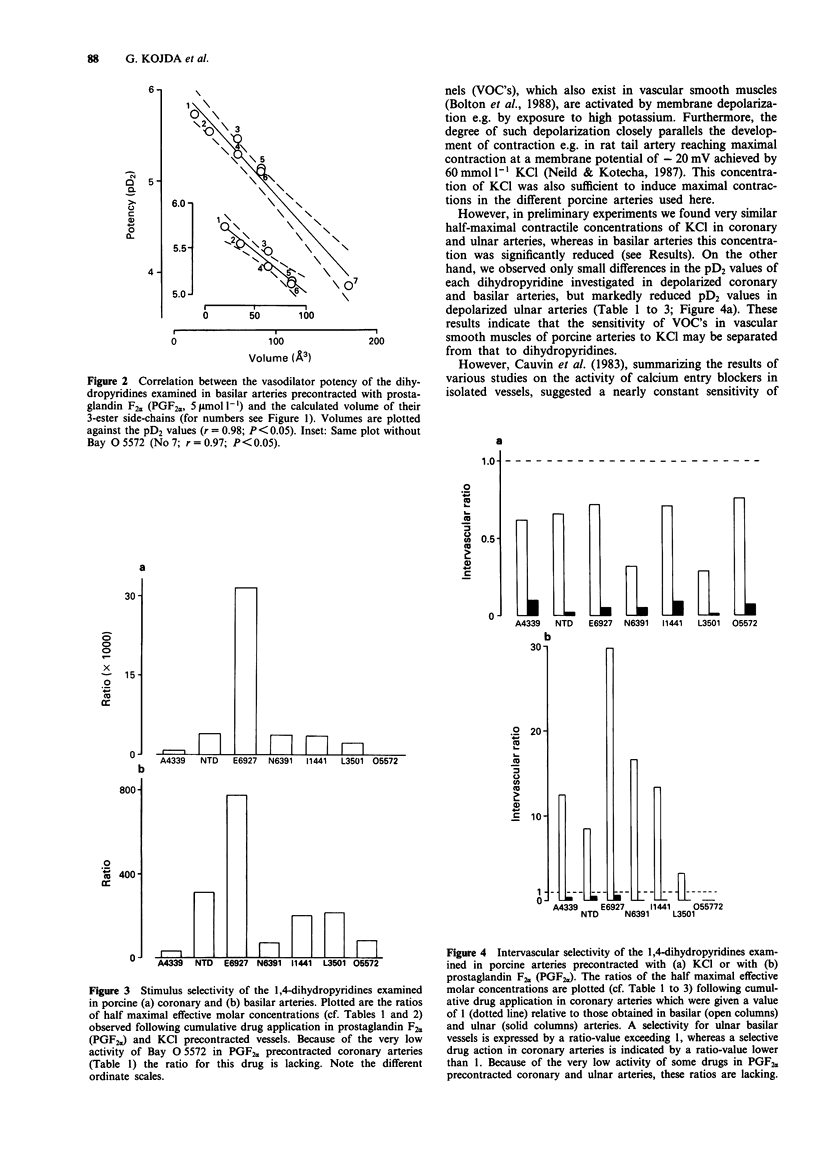

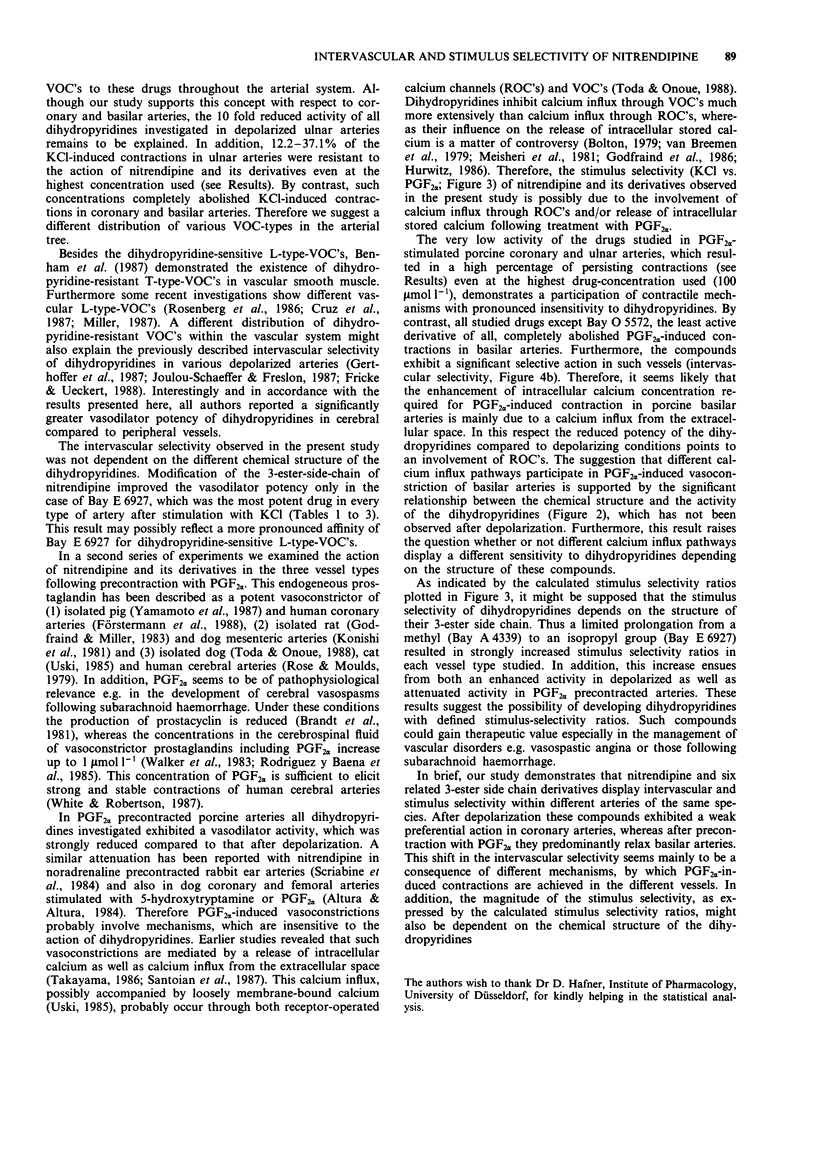

1. Dihydropyridine-type calcium entry blockers exhibit a different vasodilator potency depending on the arterial tissue (intervascular selectivity) as well as on the precontracting stimulus used (stimulus selectivity). In addition, the structure of their ester side chains seems to influence their activity. 2. Vascular activity of nitrendipine and six related 3-ester side chain derivatives was investigated in isolated coronary, ulnar and basilar arteries of the pig following precontraction with KCl or prostaglandin F2 alpha (PGF2 alpha). 3. After depolarization, all dihydropyridines exhibited a weak preferential action on coronary arteries. Bay E 6927 produced the strongest effect in all vessel types. By contrast, precontraction with PGF2 alpha resulted in a marked preferential action in basilar arteries, although higher concentrations of the dihydropyridines were required for half maximal vasorelaxation. In each case, ulnar arteries were less sensitive. 4. Except with Bay O 5572, the most bulky substituted and least active derivative, only moderate differences were observed within the dihydropyridines studied. On the other hand, there was a pronounced increase in the ratios of the half maximal active concentrations required after precontraction of the vessels with PGF2 alpha compared to KCl (stimulus selectivity) following a limited prolongation of the 3-ester side chain up to an isopropyl-group. 5. It is suggested that the observed shift in the intervascular selectivity after precontraction with PGF2 alpha is a consequence of different contractile mechanisms in the three vessel types studied. The degree of the stimulus selectivity may also depend on the structure of the dihydropyridines.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bolton T. B., MacKenzie I., Aaronson P. I. Voltage-dependent calcium channels in smooth muscle cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;12 (Suppl 6):S3–S7. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198812006-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton T. B. Mechanisms of action of transmitters and other substances on smooth muscle. Physiol Rev. 1979 Jul;59(3):606–718. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert F., Horstmann H., Meyer H., Vater W. Einfluss der Esterfunktion auf die vasodilatierenden Eigenschaften von 1,4-Dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-4-nitrophenyl-pyridin-3,5-dicarbonsäureestern. Arzneimittelforschung. 1979;29(2):226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt L., Ljunggren B., Andersson K. E., Hindfelt B. Individual variations in response of human cerebral arterioles to vasoactive substances, human plasma, and CSF from patients with aneurysmal SAH. J Neurosurg. 1981 Sep;55(3):431–437. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.3.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauvin C., Loutzenhiser R., Van Breemen C. Mechanisms of calcium antagonist-induced vasodilation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1983;23:373–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.23.040183.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz L. J., Johnson D. S., Olivera B. M. Characterization of the omega-conotoxin target. Evidence for tissue-specific heterogeneity in calcium channel types. Biochemistry. 1987 Feb 10;26(3):820–824. doi: 10.1021/bi00377a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke U., Klaus W., Stein B. Novel halogenated dihydropyridine derivatives with high vascular selectivity. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1988 Oct;338(4):449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00172126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förstermann U., Mügge A., Alheid U., Haverich A., Frölich J. C. Selective attenuation of endothelium-mediated vasodilation in atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Circ Res. 1988 Feb;62(2):185–190. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerthoffer W. T., Shafer P. G., Taylor S. Selectivity of phenytoin and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers for relaxation of the basilar artery. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1987 Jul;10(1):9–15. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind T., Eglème C., Finet M., Jaumin P. The actions of nifedipine and nisoldipine on the contractile activity of human coronary arteries and human cardiac tissue in vitro. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1987 Aug;61(2):79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind T., Miller R., Wibo M. Calcium antagonism and calcium entry blockade. Pharmacol Rev. 1986 Dec;38(4):321–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner D., Heinen E., Noack E. Mathematical analysis of concentration-response relationships. Method for the evaluation of the ED50 and the number of binding sites per receptor molecule using the logit transformation. Arzneimittelforschung. 1977;27(10):1871–1873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz L. Pharmacology of calcium channels and smooth muscle. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1986;26:225–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.26.040186.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julou-Schaeffer G., Freslon J. L. Compared effects of calcium entry blockers on calcium-induced tension in rat isolated cerebral and peripheral resistance vessels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987 Dec;336(6):670–676. doi: 10.1007/BF00165759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojda G., Klaus W., Werner G., Fricke U. Reduced responses of nitrendipine in PGF2 alpha-precontracted porcine isolated arteries after pretreatment with methylene blue. Basic Res Cardiol. 1990 Sep-Oct;85(5):461–466. doi: 10.1007/BF01931492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M., Toda N., Yamamoto M. Different mechanisms of action of histamine in isolated arteries of the dog. Br J Pharmacol. 1981 Sep;74(1):111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisheri K. D., Hwang O., van Breemen C. Evidence for two separated Ca2+ pathways in smooth muscle plasmalemma. J Membr Biol. 1981 Mar 15;59(1):19–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01870817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. J. Multiple calcium channels and neuronal function. Science. 1987 Jan 2;235(4784):46–52. doi: 10.1126/science.2432656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neild T. O., Kotecha N. Relation between membrane potential and contractile force in smooth muscle of the rat tail artery during stimulation by norepinephrine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and potassium. Circ Res. 1987 May;60(5):791–795. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez y Baena R., Gaetani P., Folco G., Branzoli U., Paoletti P. Cisternal and lumbar CSF concentration of arachidonate metabolites in vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage from ruptured aneurysm: biochemical and clinical considerations. Surg Neurol. 1985 Oct;24(4):428–432. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(85)90303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. A., Moulds R. F. Pharmacological comparison of isolated human cerebral and digital arteries. Stroke. 1979 Nov-Dec;10(6):736–741. doi: 10.1161/01.str.10.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg R. L., Hess P., Reeves J. P., Smilowitz H., Tsien R. W. Calcium channels in planar lipid bilayers: insights into mechanisms of ion permeation and gating. Science. 1986 Mar 28;231(4745):1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.2420007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoian E. C., Angerio A. D., Fitzpatrick T. M., Rose J. C., Ramwell P. W., Kot P. A. Effects of intracellular and extracellular calcium blockers on the pulmonary vascular responses to PGF2 alpha and U46619. Angiology. 1987 Jan;38(1 Pt 1):51–55. doi: 10.1177/000331978703800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama T. [Effects of prostaglandins on the contractile mechanism, especially on an intracellular Ca store in uterine smooth muscle cells]. Nihon Heikatsukin Gakkai Zasshi. 1986 Feb;22(1):31–42. doi: 10.1540/jsmr1965.22.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda N., Onoue H. Prostaglandin F2 alpha-induced contraction in isolated dog cerebral, coronary and mesenteric arteries soaked in excess potassium. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1988 Jun;47(2):204–207. doi: 10.1254/jjp.47.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uski T. K. Cellular calcium and the contraction induced by prostaglandin F2 alpha in feline cerebral arteries. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1985 Feb;56(2):117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1985.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker V., Pickard J. D., Smythe P., Eastwood S., Perry S. Effects of subarachnoid haemorrhage on intracranial prostaglandins. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983 Feb;46(2):119–125. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.46.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R. P., Robertson J. T. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of human cerebral arteries in the genesis of vasospasm. Neurosurgery. 1987 Oct;21(4):523–531. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198710000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Tomoike H., Egashira K., Nakamura M. Attenuation of endothelium-related relaxation and enhanced responsiveness of vascular smooth muscle to histamine in spastic coronary arterial segments from miniature pigs. Circ Res. 1987 Dec;61(6):772–778. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]