Abstract

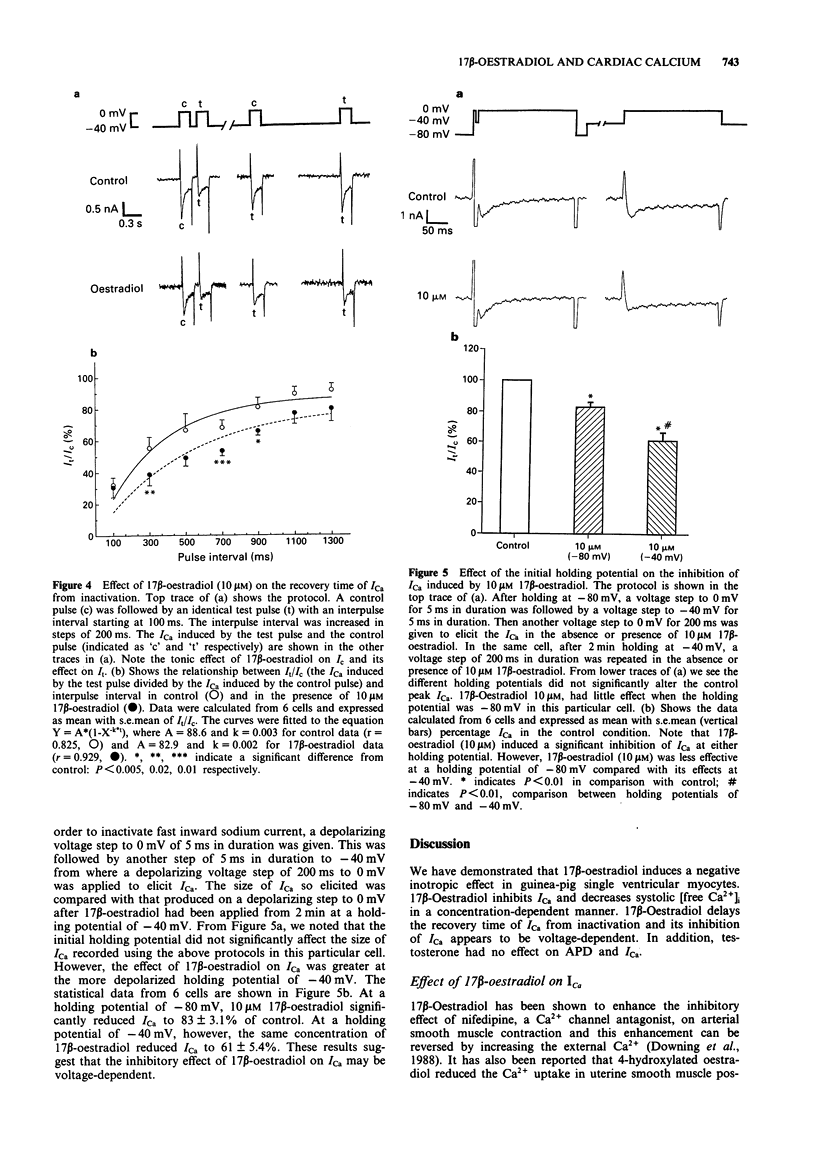

1. The effect of 17 beta-oestradiol on cardiac cell contraction, inward Ca2+ current and intracellular free Ca2+ ([free Ca2+]i) was investigated in guinea-pig single, isolated ventricular myocytes. The changes of cell length were measured by use of a photodiode array, the voltage-clamp experiments were performed with a switch clamp system and [free Ca2+]i was measured with the Ca2+ indicator, Fura-2. 2. 17 beta-Oestradiol (10, 30 microM) caused a decrease in cell shortening at both 22 and 35 degrees C. This negative inotropic effect was accompanied by a decrease in action potential duration mainly brought about by a shortening of the plateau region of the action potential. 17 beta-Oestradiol (10, 30 microM) induced a similar decrease in cell shortening in voltage-clamped and current-clamped cells. 3. In Fura-2 loaded cells, 17 beta-oestradiol (10 and 30 microM) decreased systolic Fura-2 fluorescence to 72 +/- 7% and 47 +/- 4% (n = 6, P less than 0.001) of control respectively. 17 beta-Oestradiol (10 microM) had no significant effect on diastolic Fura-2 fluorescence, but at higher concentration (30 microM) induced a slight decrease in resting Fura-2 fluorescence. The effect of 17 beta-oestradiol was reversible after 1-2 min of washout of the steroid. 4. 17 beta-Oestradiol (10 and 30 microM) decreased the peak inward Ca2+ current (ICa), which was sensitive to [Ca2+]o, dihydropyridines and isoprenaline, to 59 +/- 3% and 39 +/- 5% (n = 7 approximately 9, P less than 0.01) respectively, without producing any significant change in the shape of the current-voltage relationship.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bean B. P. Nitrendipine block of cardiac calcium channels: high-affinity binding to the inactivated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Oct;81(20):6388–6392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belles B., Malécot C. O., Hescheler J., Trautwein W. "Run-down" of the Ca current during long whole-cell recordings in guinea pig heart cells: role of phosphorylation and intracellular calcium. Pflugers Arch. 1988 Apr;411(4):353–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00587713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing S. J., Hollingsworth M., Miller M. The influence of oestrogen and progesterone on the actions of two calcium entry blockers in the rat uterus. J Endocrinol. 1988 Aug;118(2):251–258. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1180251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Appraisal of the physiological relevance of two hypothesis for the mechanism of calcium release from the mammalian cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum: calcium-induced release versus charge-coupled release. Mol Cell Biochem. 1989 Sep 7;89(2):135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00220765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Simulated calcium current can both cause calcium loading in and trigger calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned canine cardiac Purkinje cell. J Gen Physiol. 1985 Feb;85(2):291–320. doi: 10.1085/jgp.85.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Time and calcium dependence of activation and inactivation of calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned canine cardiac Purkinje cell. J Gen Physiol. 1985 Feb;85(2):247–289. doi: 10.1085/jgp.85.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D., Noble D., Spindler A. J. Use-dependent reduction and facilitation of Ca2+ current in guinea-pig myocytes. J Physiol. 1988 Nov;405:439–460. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley R. W., Hume J. R. An intrinsic potential-dependent inactivation mechanism associated with calcium channels in guinea-pig myocytes. J Physiol. 1987 Aug;389:205–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish J. C., Boyett M. R. A simple electronic circuit for monitoring changes in the duration of the action potential. Pflugers Arch. 1983 Aug;398(3):233–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00657157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. S., Marban E., Tsien R. W. Inactivation of calcium channels in mammalian heart cells: joint dependence on membrane potential and intracellular calcium. J Physiol. 1985 Jul;364:395–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod K. T., Harding S. E. Effects of phorbol ester on contraction, intracellular pH and intracellular Ca2+ in isolated mammalian ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1991 Dec;444:481–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill H. C., Jr, Anselmo V. C., Buchanan J. M., Sheridan P. J. The heart is a target organ for androgen. Science. 1980 Feb 15;207(4432):775–777. doi: 10.1126/science.6766222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble D. The surprising heart: a review of recent progress in cardiac electrophysiology. J Physiol. 1984 Aug;353:1–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raddino R., Manca C., Poli E., Bolognesi R., Visioli O. Effects of 17 beta-estradiol on the isolated rabbit heart. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1986 May;281(1):57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe M. W., Lemasters J. J., Herman B. Assessment of Fura-2 for measurements of cytosolic free calcium. Cell Calcium. 1990 Feb-Mar;11(2-3):63–73. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salata J. J., Wasserstrom J. A. Effects of quinidine on action potentials and ionic currents in isolated canine ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1988 Feb;62(2):324–337. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti M. C., Kass R. S. Voltage-dependent block of calcium channel current in the calf cardiac Purkinje fiber by dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists. Circ Res. 1984 Sep;55(3):336–348. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice S. L., Ford S. P., Rosazza J. P., Van Orden D. E. Interaction of 4-hydroxylated estradiol and potential-sensitive Ca2+ channels in altering uterine blood flow during the estrous cycle and early pregnancy in gilts. Biol Reprod. 1987 Mar;36(2):369–375. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod36.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice S. L., Ford S. P., Rosazza J. P., Van Orden D. E. Role of 4-hydroxylated estradiol in reducing Ca2+ uptake of uterine arterial smooth muscle cells through potential-sensitive channels. Biol Reprod. 1987 Mar;36(2):361–368. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod36.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf W. E., Sar M., Aumüller G. The heart: a target organ for estradiol. Science. 1977 Apr 15;196(4287):319–321. doi: 10.1126/science.847474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]