Abstract

1. The generation of nitric oxide (NO) from L-arginine by NO synthases (NOS) can be inhibited by guanidines, amidines and S-alkylisothioureas. Unlike most L-arginine based inhibitors, however, some guanidines and S-alkylisothioureas, in particular aminoethylisothiourea (AETU), show selectivity towards the inducible isoform (iNOS) over the constitutive isoforms (endothelial, ecNOS and brain isoform, bNOS) and so may be of therapeutic benefit. In the present study we have investigated the effects of AETU and other aminoalkylisothioureas on the activities of iNOS, ecNOS and bNOS. 2. AETU, aminopropylisothiourea (APTU) and their derivatives containing alkyl substituents on one of the amidino nitrogens, potently inhibit nitrite formation by immunostimulated J774 macrophages (a model of iNOS activity) with EC50 values ranging from 6-30 microM (EC50 values for NG-methyl-L-arginine (L-NMA) and NG-nitro-L-arginine were 159 and > 1000 microM, respectively). The inhibitory effects of these aminoalkylisothioureas (AATUs) were attentuated by L-arginine in the incubation medium, indicating that these agents may complete with L-arginine for its binding site on NOS. 3. The above AATUs undergo chemical conversion in neutral or basic solution (pH 7 or above) as indicated by (1) the disappearance of AATUs from solution as measured by h.p.l.c., (2) the generation of free thiols not previously present and (3) the isolation of species (as picrate and flavianate salts) from neutral or basic solutions of AATUs that are different from those obtained from acid solutions. 4. Mercaptoalkylguanidines (MAGs) were prepared and shown to be potent inhibitors of iNOS activity with EC50s comparable to those of their isomeric AATUs. 5. These findings suggest that certain AATUs exert their potent inhibitory effects through intramolecular rearrangement to mercaptoalkylguanidines (MAGs) at physiological pH. Those AATUs not capable of such rearrangement do not exhibit the same degree of inhibition of iNOS. 6. In contrast to their potent effects on iNOS, some AATUs and MAGs were 20-100 times weaker than NG-methyl-L-arginine and NG-nitro-L-arginine as inhibitors of ecNOS as assessed by their effects on the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline in homogenates of bovine endothelial cells and by their pressor effects in anaesthetized rats. Thus mercaptoalkylguanidines represent a new class of NOS inhibitors with preference towards iNOS. 7. AETU and mercaptoethylguanidine (MEG), when given as infusions, gave slight decreases in MAP in control rats. However, infusions of AETU or MEG to endotoxin-treated rats caused an increase in MAP and restored 80% of the endotoxin-induced fall in MAP. 8. High doses of MEG (30-60 mg kg-1) caused a decrease in MAP of normal rats. This depressor effect may be a consequence of the in vivo oxidation of MEG to the disulphide, guanidinoethyldisulphide (GED), which caused pronounced, transient hypotensive responses in anaesthetized rats and caused endothelium-independent vasodilator responses in precontracted rat aortic rings in vitro. 9. In some cases, slight differences were observed in the activities of AATUs and the corresponding MAGs. These may be explained by the formation of other species from AATUs in physiological media. For example, AETU can give rise to small amounts of the potent ecNOS inhibitor, 2-aminothiazoline, in addition to MEG. This may account for the differences in the in vitro and in vivo effects of AETU and MEG. 10. In conclusion, the in vitro and in vivo effects of AETU and related aminoalkylisothioureas can be explained in terms of their intramolecular rearrangement to generate mercaptoalkylguanidines, a novel class of selective inhibitors of iNOS.

Full text

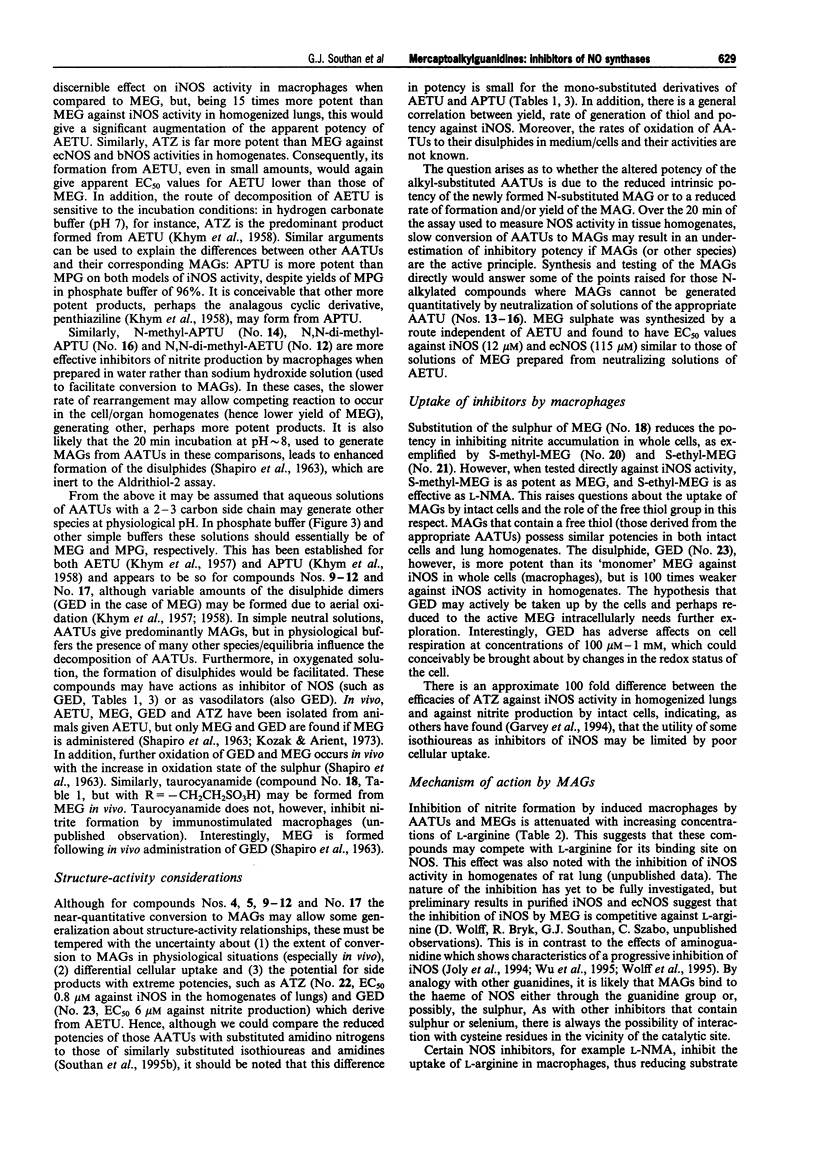

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

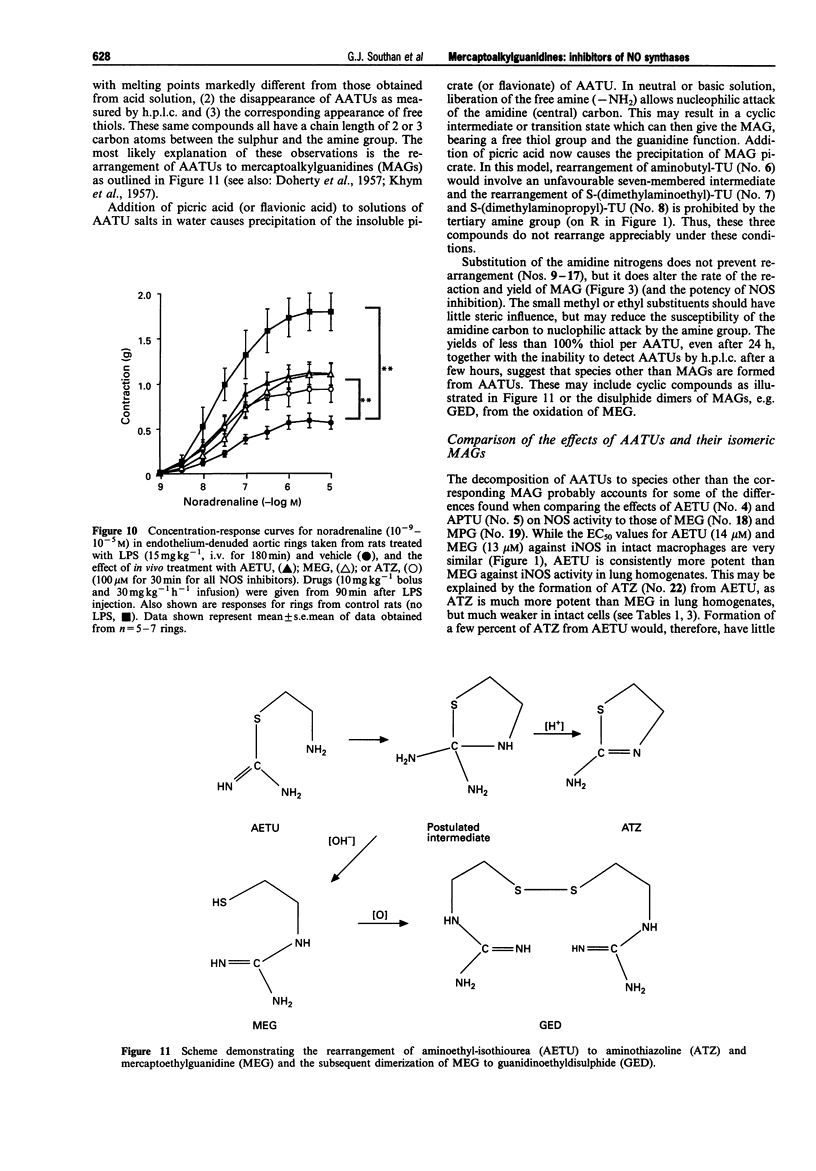

- Baydoun A. R., Bogle R. G., Pearson J. D., Mann G. E. Discrimination between citrulline and arginine transport in activated murine macrophages: inefficient synthesis of NO from recycling of citrulline to arginine. Br J Pharmacol. 1994 Jun;112(2):487–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

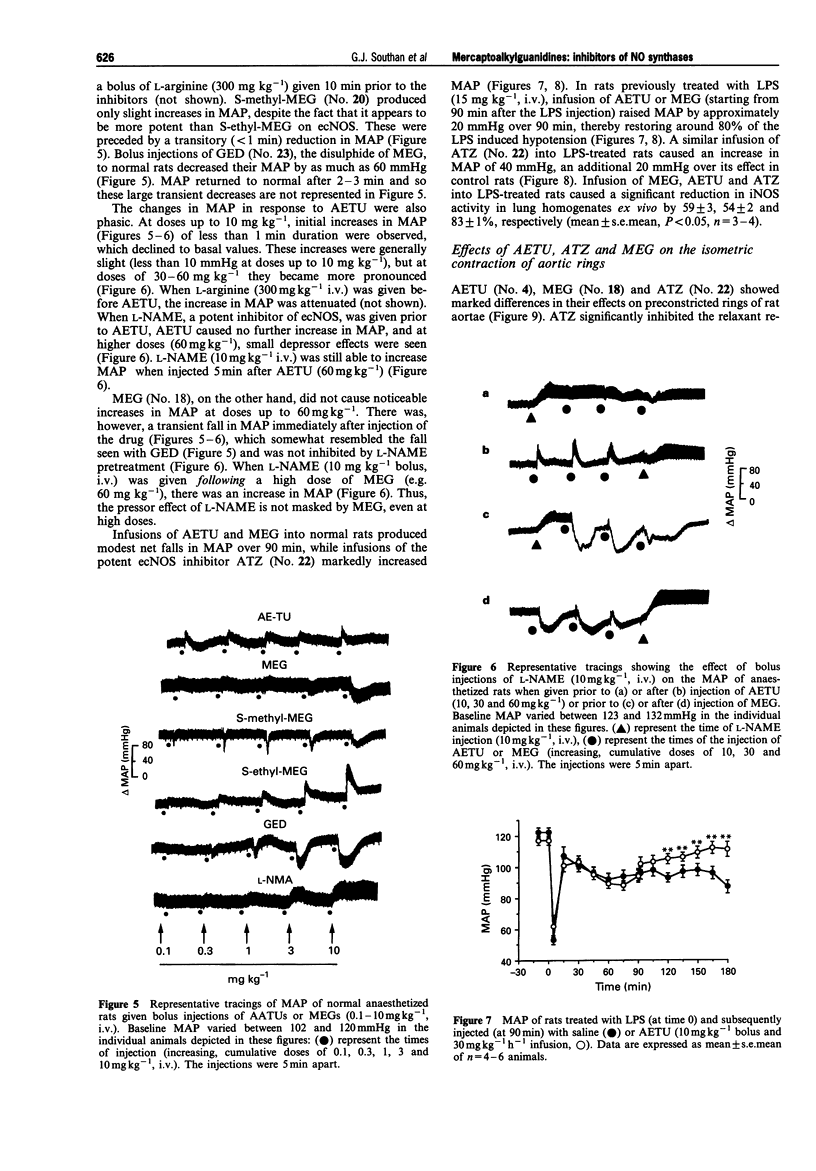

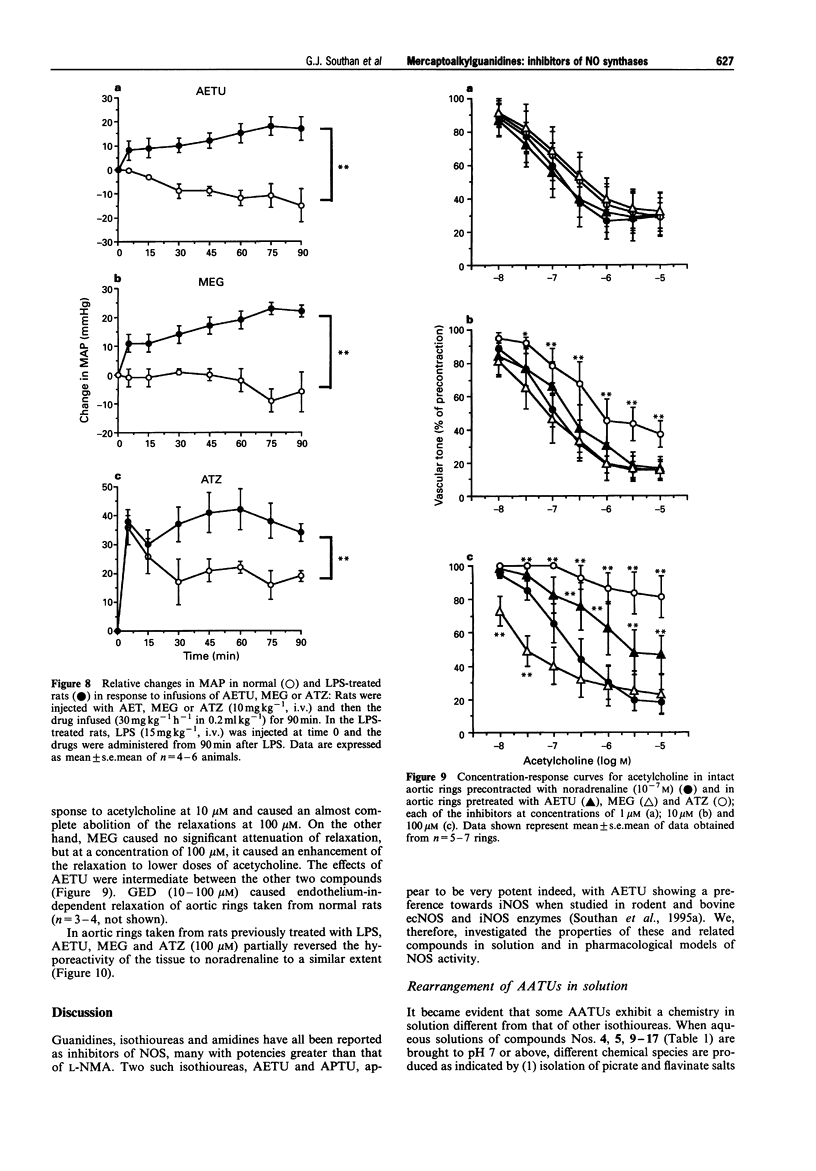

- Bogle R. G., Moncada S., Pearson J. D., Mann G. E. Identification of inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase that do not interact with the endothelial cell L-arginine transporter. Br J Pharmacol. 1992 Apr;105(4):768–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett J. A., Tilton R. G., Chang K., Hasan K. S., Ido Y., Wang J. L., Sweetland M. A., Lancaster J. R., Jr, Williamson J. R., McDaniel M. L. Aminoguanidine, a novel inhibitor of nitric oxide formation, prevents diabetic vascular dysfunction. Diabetes. 1992 Apr;41(4):552–556. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., London E. D., Bredt D. S., Snyder S. H. Nitric oxide mediates glutamate neurotoxicity in primary cortical cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Jul 15;88(14):6368–6371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinerman J. L., Lowenstein C. J., Snyder S. H. Molecular mechanisms of nitric oxide regulation. Potential relevance to cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 1993 Aug;73(2):217–222. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FASTIER F. N. Structure-activity relationships of amidine derivatives. Pharmacol Rev. 1962 Mar;14:37–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J. Glutamate, nitric oxide and cell-cell signalling in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1991 Feb;14(2):60–67. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90022-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey E. P., Oplinger J. A., Tanoury G. J., Sherman P. A., Fowler M., Marshall S., Harmon M. F., Paith J. E., Furfine E. S. Potent and selective inhibition of human nitric oxide synthases. Inhibition by non-amino acid isothioureas. J Biol Chem. 1994 Oct 28;269(43):26669–26676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassetti D. R., Murray J. F., Jr Determination of sulfhydryl groups with 2,2'- or 4,4'-dithiodipyridine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1967 Mar;119(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(67)90426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S. S., Jaffe E. A., Levi R., Kilbourn R. G. Cytokine-activated endothelial cells express an isotype of nitric oxide synthase which is tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent, calmodulin-independent and inhibited by arginine analogs with a rank-order of potency characteristic of activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991 Aug 15;178(3):823–829. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90965-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S. S., Stuehr D. J., Aisaka K., Jaffe E. A., Levi R., Griffith O. W. Macrophage and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthesis: cell-type selective inhibition by NG-aminoarginine, NG-nitroarginine and NG-methylarginine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Jul 16;170(1):96–103. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91245-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan K., Heesen B. J., Corbett J. A., McDaniel M. L., Chang K., Allison W., Wolffenbuttel B. H., Williamson J. R., Tilton R. G. Inhibition of nitric oxide formation by guanidines. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993 Nov 2;249(1):101–106. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino T., Tana-ami K., Yamada K., Akaboshi S. Radiation-protective agents. I. Studies on N-alkylated-2-(2-aminoethyl)thiopseudoureas and 1,1-(dithioethylene)diguanidines. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1966 Nov;14(11):1193–1201. doi: 10.1248/cpb.14.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly G. A., Ayres M., Chelly F., Kilbourn R. G. Effects of NG-methyl-L-arginine, NG-nitro-L-arginine, and aminoguanidine on constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat aorta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994 Feb 28;199(1):147–154. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozák I., Arient M. Metabolism and radioprotective effect of AET and MEG in organism. Strahlentherapie. 1973 Sep;146(3):367–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert L. E., Whitten J. P., Baron B. M., Cheng H. C., Doherty N. S., McDonald I. A. Nitric oxide synthesis in the CNS endothelium and macrophages differs in its sensitivity to inhibition by arginine analogues. Life Sci. 1991;48(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90426-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebmann J., DeLuca A. M., Coffin D., Keefer L. K., Venzon D., Wink D. A., Mitchell J. B. In vivo radiation protection by nitric oxide modulation. Cancer Res. 1994 Jul 1;54(13):3365–3368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAllister R. J., Whitley G. S., Vallance P. Effects of guanidino and uremic compounds on nitric oxide pathways. Kidney Int. 1994 Mar;45(3):737–742. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marletta M. A. Nitric oxide synthase structure and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jun 15;268(17):12231–12234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misko T. P., Moore W. M., Kasten T. P., Nickols G. A., Corbett J. A., Tilton R. G., McDaniel M. L., Williamson J. R., Currie M. G. Selective inhibition of the inducible nitric oxide synthase by aminoguanidine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993 Mar 16;233(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90357-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane M., Klinghofer V., Kuk J. E., Donnelly J. L., Budzik G. P., Pollock J. S., Basha F., Carter G. W. Novel potent and selective inhibitors of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Mol Pharmacol. 1995 Apr;47(4):831–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Nitric oxide as a secretory product of mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1992 Sep;6(12):3051–3064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa H., Sugawara K. Structure-activity relationship of alkylguanidines on smooth muscle organs. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1968 Dec;16(12):2376–2382. doi: 10.1248/cpb.16.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAPIRA R., DOHERTY D. G., BURNETT W. T., Jr Chemical protection against ionizing radiation. III. Mercaptoalkylguanidines and related isothiuronium compounds with protective activity. Radiat Res. 1957 Jul;7(1):22–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAPIRO B., SCHWARTZ E. E., KOLLMANN G. The mechanism of action of AET. IV. The distribution and the chemical forms of 2-mercaptoethylguanidine and bis(2-guanidoethyl) disulfide in protected mice. Radiat Res. 1963 Jan;18:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan G. J., Szabó C., Thiemermann C. Isothioureas: potent inhibitors of nitric oxide synthases with variable isoform selectivity. Br J Pharmacol. 1995 Jan;114(2):510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó C. Alterations in nitric oxide production in various forms of circulatory shock. New Horiz. 1995 Feb;3(1):2–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó C., Southan G. J., Thiemermann C. Beneficial effects and improved survival in rodent models of septic shock with S-methylisothiourea sulfate, a potent and selective inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Dec 20;91(26):12472–12476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó C., Southan G. J., Thiemermann C., Vane J. R. The mechanism of the inhibitory effect of polyamines on the induction of nitric oxide synthase: role of aldehyde metabolites. Br J Pharmacol. 1994 Nov;113(3):757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemermann C., Ruetten H., Wu C. C., Vane J. R. The multiple organ dysfunction syndrome caused by endotoxin in the rat: attenuation of liver dysfunction by inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase. Br J Pharmacol. 1995 Dec;116(7):2845–2851. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane J. R. The Croonian Lecture, 1993. The endothelium: maestro of the blood circulation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994 Jan 29;343(1304):225–246. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff D. J., Lubeskie A. Aminoguanidine is an isoform-selective, mechanism-based inactivator of nitric oxide synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995 Jan 10;316(1):290–301. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrall N. K., Lazenby W. D., Misko T. P., Lin T. S., Rodi C. P., Manning P. T., Tilton R. G., Williamson J. R., Ferguson T. B., Jr Modulation of in vivo alloreactivity by inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1995 Jan 1;181(1):63–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. C., Chen S. J., Szabó C., Thiemermann C., Vane J. R. Aminoguanidine attenuates the delayed circulatory failure and improves survival in rodent models of endotoxic shock. Br J Pharmacol. 1995 Apr;114(8):1666–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. C., Szabó C., Chen S. J., Thiemermann C., Vane J. R. Activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase by a factor other than nitric oxide or carbon monoxide contributes to the vascular hyporeactivity to vasoconstrictor agents in the aorta of rats treated with endotoxin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994 May 30;201(1):436–442. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q., Nathan C. The high-output nitric oxide pathway: role and regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 1994 Nov;56(5):576–582. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.5.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]