Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus IL-10 (ebvIL-10) mimics the biological functions of cellular IL-10 including a number of immunoinhibitory activities on diverse immune cells. Characterization of ebvIL-10 and several mutants, expressed in Escherichia coli, by gel filtration chromatography and mass spectrometry revealed a +1 frameshift of ebvIL-10 expression. The frameshift is caused by the rare AGG codon at ebvIL-10 Arg159, which is preceded by the most inefficient stop signal, UGAC. The frameshift was corrected by substituting the rare AGG codon with an abundant arginine codon, CGU, or by enhancing the level of tRNA that decodes the AGG codon. As a result, ebvIL-10 expression levels increased by ~3-fold and the purity of the protein improved from 85–95% to 98–99%. The correction of the frameshift has been essential for continuing structural and biophysical studies of ebvIL-10.

Introduction

Cellular IL-10 (cIL-10) and Epstein-Barr virus IL-10 (ebvIL-10) modulate diverse immune responses by engaging two cell surface receptor chains (IL-10R1 and IL-10R2) [1]. cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 are mainly involved in restraining inflammatory responses by exerting potent immunoinhibitory and anti-inflammatory activities on antigen presenting cells such as monocytes and macrophages [2, 3]. In contrast to their shared immunoinhibitory functions, ebvIL-10 does not induce several cIL-10 immunostimulatory activities, including costimulation of mast cell and thymocyte proliferation [4–6]. The functional differences between ebvIL-10 and cIL-10 have been correlated with a difference in IL-10R1 affinity between ebvIL-10 and cIL-10 [6, 7].

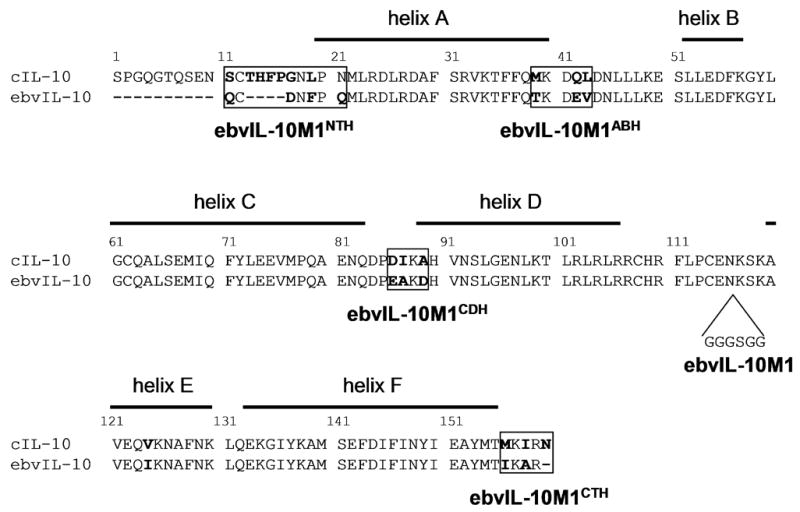

cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 are L-shaped intercalated non-covalent homodimers. Each domain contains 6 helices that adopt a 6-helix bundle fold [8–10]. cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 bind the extracellular domain of IL-10R1 (sIL-10R1) with a stoichiometry of 2:4 in solution [11]. Monomeric IL-10 (IL-10M1) was engineered by inserting six residues, GGGSGG, between residues 116 and 117 (Fig. 1) [12, 13]. IL-10M1 has been shown to be biologically active [12, 14] and its structure is essentially identical to one domain of IL-10 [15]. The simple 1:1 stoichiometry of the interaction between IL-10M1 and sIL-10R1 has been used to derive accurate binding constants using isothermal titration calorimetry and surface plasmon resonance techniques [12, 13, 16].

Fig 1.

The alignment of cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 amino acid sequences. Sequence differences between cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 are shown in bold. Lines above the cIL-10 sequence represent α-helices defined by IL-10 structures. IL-10M1 contains additional amino acids, GGGSGG, between IL-10 residues 116 and 117. Monomeric ebvIL-10/cIL-10 chimeras were made by replacing the cIL-10 sequence, located in each of four boxed regions, into ebvIL-10M1.

Expression of heterologous proteins in Escherichia coli cells can lead to translational errors, such as amino acid substitution, frameshift, and codon hopping, due to the specific bias of E. coli in codon usage [17–21]. Codon usage is largely correlated with the abundance of cognate tRNA species in E. coli [22]. Excessive rare codons in mRNA can result in ribosome stalling and mistranslational errors due to a limited tRNA supply. Here, we report that the rare AGG codon of ebvIL-10 Arg159, located next to the most inefficient translational termination signal (UGAC), causes a +1 frameshift during heterologous ebvIL-10 expression in E. coli. The frameshift was prevented either by replacing the rare arginine AGG codon with a frequently used arginine codon, CGU, or by increasing rare arginyl tRNAAGG levels. As a result, the expression level of ebvIL-10 increased by ~3-fold and the homogeneity of purified ebvIL-10 samples substantially improved. The improvement has been essential for X-ray, NMR and binding analyses to characterize the interaction between ebvIL-10 and IL-10 receptor chains.

Materials and Methods

Construction of vectors that encode monomeric ebvIL-10/cIL-10 chimeras

cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 were cloned into an expression vector, pET-32, and their monomeric forms (cIL-10M1 and ebvIL-10M1, respectively) were engineered, as previously described [12, 13]. In order to reveal the role of sequence differences between cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 in an ebvIL-10 frameshift, plasmids for the expression of four monomeric ebvIL-10/cIL-10 chimeras were generated. The chimeras correspond to ebvIL-10M1 containing the N-terminal sequence (ebvIL-10M1NTH), the AB loop sequence (ebvIL-10M1ABH), the CD loop sequence (ebvIL-10M1CDH), or the C-terminal sequence (ebvIL-10M1CTH) of cIL-10 (Fig. 1). ebvIL-10M1NTH or ebvIL-10M1CTH expression vectors were constructed by PCR amplification followed by cloning into the pET-32 vector. ebvIL-10M1NTH cDNA was amplified using a 5′ primer (primer 1), containing an NdeI site and the N-terminal sequence of cIL-10, and a 3′ external primer (primer 2) (Table 1). ebvIL-10M1CTH cDNA was generated by PCR using a 5′ external primer (primer 3) and a 3′ primer containing an XhoI site and the C-terminal sequence of cIL-10 (Table 1). The PCR products were digested with NdeI and XhoI, and then ligated to NdeI- and XhoI-cut pET-32. Mutagenesis to generate ebvIL-10M1ABH or ebvIL-10M1CDH expression vectors was performed by the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using internal primers containing specific mutations (ebvIL-10M1ABH, primers 5 and 6; ebvIL-10M1CDH, primers 7 and 8) (Table 1). The sequences of the constructs obtained were verified by DNA sequencing.

Table 1.

Primers used for amplifying monomeric ebvIL-10/cIL-10 chimera cDNA.

| Primer name | Primer orientation | Primer sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Primer 1 | Forward | 5′-AGATATACATATGAGCTGCACCCACTTCCCAGGCAACCTGCCTAACATGTTGAGGGACCTAAGAGATG-3′ |

| Primer 2 | Reverse | 5′-CCAAGGGGTTATGCTAGTTATTGC-3′ |

| Primer 3 | Forward | 5′-ACGACTCACTATAGGGGAATTGTG-3′ |

| Primer 4 | Reverse | 5′-GTGCTCGAGTCAGTTTCGTATCTTCATTGTCATGTATGCTTCTATGTAG-3′ |

| Primer 5 | Forward | 5′-GTGTTAAAACCTTTTTCCAGATGAAGGACCAGTTAGATAACCTTTTGCTCAAGG-3′ |

| Primer 6 | Reverse | 5′-CCTTGAGCAAAAGGTTATCTAACTGGTCCTTCATCTGGAAAAAGGTTTTAACAC-3′ |

| Primer 7 | Forward | 5′-CCAGGACCCTGACATCAAAGCCCATGTCAATTCTTTG-3′ |

| Primer 8 | Reverse | 5′-CAAAGAATTGACATGGGCTTTGATGTCAGGGTCCTGG-3′ |

Restriction sites are underlined (primer1, NdeI site; primer 4, XhoI site). The sequence of cIL-10 is shown in bold.

Protein expression, refolding, and purification

Competent E. coli strains, BL21 (DE3) or Rosetta2 (DE3) (Novagen), were transformed with plasmids which express cIL-10, ebvIL-10, or their variants. For over-expression, cells were grown in Luria–Bertani medium, containing appropriate antibiotics (100 μg/ml carbenicillin for the BL21 (DE3) strain; 100 μg/ml carbenicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol for the Rosetta2 (DE3) strain), at 37 °C in a shaking incubator (200 rpm). When the optical density (OD600) reached 0.6, protein synthesis was induced by 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). Following addition of IPTG, the cells were grown at 37 °C for 3 additional hours. Protein expression levels were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis.

cIL-10, ebvIL-10, and their variants were refolded since the expressed proteins predominantly formed inclusion bodies [9, 12, 13]. After expression, cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cells (wet weight, ~3 g) obtained from 1 L culture were broken by sonication in 50 ml of resuspension buffer (RS buffer), consisting of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Inclusion bodies were obtained by centrifugation, and washed in 50 ml of fresh RS buffer by performing two cycles of sonication and centrifugation. The purified inclusion bodies were solubilized using a denaturing buffer containing 6 M guanidine HCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2.5 mM EDTA, and 5 mM dithiothreitol. The concentration of the denatured protein was adjusted to 10 mg/ml assuming an extinction coefficient of 1.0 ml mg−1 cm−1 at 280 nm. Refolding was carried out by rapidly diluting the solubilized protein by 10-fold in refolding buffer (50 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2.5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM oxidized glutathione, and 2 mM reduced glutathione).

The refolded protein was first loaded onto a Poros HS20 cation-exchange column (column volume, 1.6 ml) that had been equilibrated in 20 mM PIPES, pH 6.5, and eluted using a 0–0.5 M NaCl gradient in 20 mM PIPES, pH 6.5. The eluted protein was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0 and further purified using a Poros HQ20 anion-exchange column (column volume, 1.6 ml) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0. Protein flowing through the HQ20 column was collected and purified by gel filtration chromatography using two serially connected Superdex 200 HR 10/30 columns (column volume, 24 ml each) equilibrated in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl. Only ~5% of expressed ebvIL-10 protein was recovered after refolding followed by three consecutive purification steps. The relatively low yield of correctly folded protein is thought to be due to inefficient disulfide bond formation, which leads to considerable protein precipitation during refolding. The size of the purified proteins was confirmed by MALDI-TOF (Perspective Biosystems) or ESI-TOF (Micromass LCT) mass spectrometry.

Proteolysis and mass spectrometry

Purified ebvIL-10M1NTH and its frameshift were digested using trypsin or carboxypeptidase Y with a sample:protease ratio of 25:1. The reaction was performed at 4 °C overnight. The digestion was monitored by SDS-PAGE analysis. The trypsin digested samples were further analyzed using ESI-TOF mass spectrometry (Micromass LCT).

Results

Characterization of an impurity observed during ebvIL-10 purification

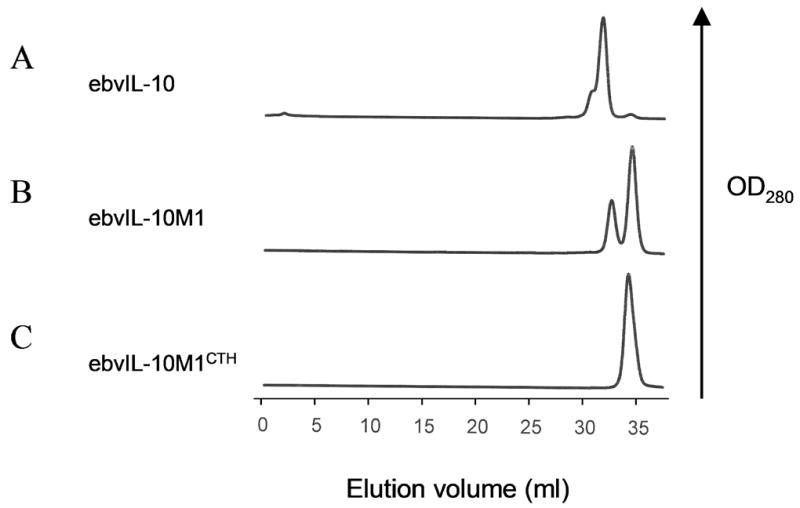

Different elution profiles were obtained for E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain expressed cIL-10 and ebvIL-10 by preparative gel filtration chromatography despite their high sequence and structural similarity (Fig. 2). Dimeric cIL-10 eluted from the gel filtration column as a well defined single peak. In contrast, gel filtration chromatography of dimeric ebvIL-10 exhibited a major peak at an apparent molecular weight (MW) of ~30 kDa, corresponding to ebvIL-10, and an additional shoulder peak containing an impurity at an apparent MW of ~40 kDa (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the shoulder peak by SDS-PAGE revealed a ~20 kDa protein species, suggesting the impurity is a dimer, like ebvIL-10. Interestingly, an impurity was also detected during the purification of ebvIL-10M1, and was ~20 kDa in both gel filtration (Fig. 2B) and SDS-PAGE analyses. These suggested the impurity may be a readthrough product of the ebvIL-10 gene.

Fig. 2.

Gel filtration chromatograms obtained from the preparative purification of ebvIL-10 (A), ebvIL-10M1 (B), and ebvIL-10M1CTH (C) that were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3).

Identification of a +1 frameshift

Because the impurity was observed in ebvIL-10, but not cIL-10 purifications, it was speculated that a specific amino acid sequence difference between ebvIL-10 and cIL-10 is responsible for the impurity. Sequence differences between ebvIL-10 and cIL-10 are located in four regions; N-terminus, AB loop, CD loop, and C-terminus (Fig. 1). In order to evaluate the role of sequence differences between ebvIL-10 and cIL-10 in the impurity, gel filtration chromatography elution patterns of four monomeric ebvIL-10/cIL-10 chimeras (ebvIL-10M1NTH, ebvIL-10M1CTH, ebvIL-10M1ABH, and ebvIL-10M1CDH) were compared. The 20 kDa impurity was detected when cIL-10 sequences were substituted for ebvIL-10M1 at the N-terminus, AB loop and CD loop, but not upon substitution of the C-terminal sequence (Fig. 2C). These results suggest ebvIL-10’s C-terminal sequence, corresponding to residues 155–159, is responsible for the 20 kDa impurity.

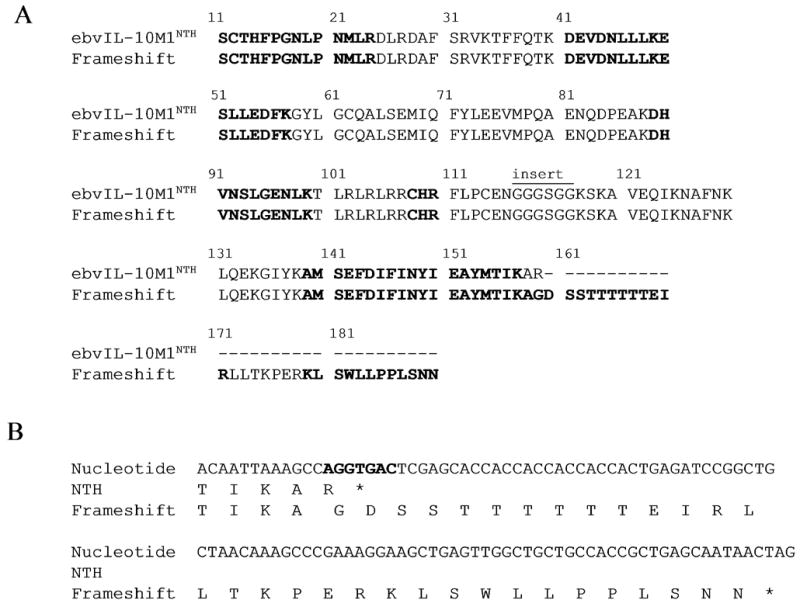

ebvIL-10M1NTH and its impurity were subjected to trypsin digestion, followed by mass spectrometry. Both proteins generated 5 common peptides corresponding to residues 41–49, 50–57, 89–99, 139–157, and a disulfide-bonded peptide 11–24/108–110 (Table 2 and Fig. 3A), indicating that the impurity is encoded from the ebvIL-10M1NTH gene. Two additional peptides were identified in the impurity with molecular weights expected from a +1 frameshift at ebvIL-10M1NTH Arg159 (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The mass of a peptide corresponded to frameshifted residues 158–171 and verified the +1 (Arg → Gly) frameshift at the DNA sequence 5′-AGGT-3′ (AGG, arginine codon; GGU, glycine codon). The second peptide corresponded to frameshifted residues 179–190 and defined the translation stop site of the frameshift. Moreover, the observed molecular weight (21,239 daltons) of the 20 kDa protein determined by mass spectrometry is in good agreement with the calculated one (21,238 daltons) of the frameshifted protein. Thus, the impurity contains ebvIL-10 residues 11–158 and 22 additional residues at the C-terminus due to the +1 frameshift at the AGG codon encoded to Arg159.

Table 2.

Peptides identified by the mass spectrometry analysis of trypsin digested ebvIL-10M1NTH and frameshift.

| Peptide | Calculated MW [charge status] | Observed MW (ebvIL-10M1NTH) | Observed MW (frameshift) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41–49 (DE…LK) | 529.79 [M+2H] | 529.77 | 529.78 |

| 50–57 (ES…FK) | 980.49 [M+H] | 980.48 | 980.51 |

| 89–99 (DH…LK) | 613.31 [M+2H] | 613.29 | 613.31 |

| 139–157 (AM…IK) | 1150.06 [M+2H] | 1150.03 | 1150.09 |

| 139–157 (AM…IK) | 767.04 [M+3H] | 767.03 | 767.03 |

| 11–24 (SC…LR) + 108–110 (CHR) | 666.98 [M+3H] | 666.95 | 666.95 |

| 11–24 (SC…LR) + 108–110 (CHR) | 500.49 [M+4H] | 500.49 | 500.48 |

| 158–171 (AG…IR) | 720.84 [M+2H] | - | 720.83 |

| 179–190 (KL…NN) | 691.40 [M+2H] | - | 691.38 |

Fig. 3.

The amino acid and nucleotide sequences of ebvIL-10M1NTH and its frameshift. (A) The amino acid sequence alignment of ebvIL-10M1NTH and the frameshift protein. The peptides identified by trypsin digestion followed by mass spectrometry are shown in bold. (B) The nucleotide sequence (the top line, Nucleotide) of the ebvIL-10M1NTH gene, and the amino acid sequences for ebvIL-10M1NTH (the second line, NTH) and the +1 frameshift protein (the bottom line, Frameshift) around the frameshift site. The nucleotide sequence of the rare AGG codon at Arg159 and the inefficient translation stop signal TGAC are shown in bold.

To determine if the additional residues adopt a three dimensional structure, ebvIL-10M1NTH and its frameshift were digested by carboxypeptidase Y. While ebvIL-10M1NTH was refractive to the digestion, the frameshift was partially degraded to several fragments which migrated between full-length ebvIL-10M1NTH and frameshift on a SDS-PAGE gel (data not shown). The result implicates that the C-terminus of the frameshift is highly disordered relative to the 6-helix bundle of ebvIL-10M1NTH.

Correction of the +1 frameshift

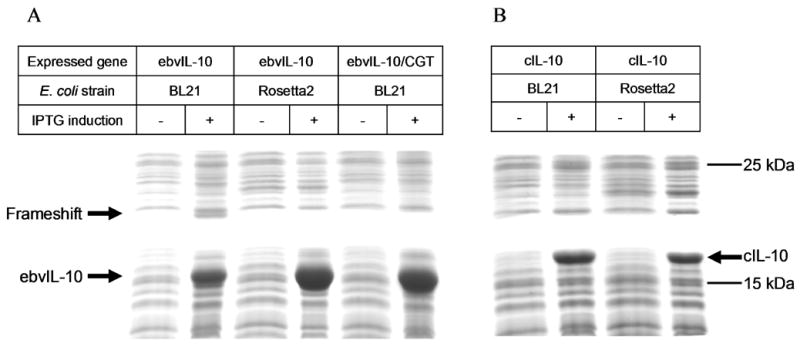

The location of the frameshift site at a rare arginine AGG codon allows us to hypothesize that the rare codon is responsible for the frameshift. To test the hypothesis and eliminate the +1 frameshift, the ebvIL-10 gene, containing a frequent arginine codon CGU at Arg 159 in place of the rare AGG codon, was expressed in an E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). Indeed, the substitution blocked the translational frameshift (Fig. 4A). As a result, ebvIL-10 expression levels increased from ~50 mg/L to ~150 mg/L, and the final ebvIL-10 yield was enhanced from 1–2 mg/L to ~9 mg/L. In addition, the homogeneity of the ebvIL-10 was improved from 85–95% to 98–99%.

Fig. 4.

Expression of ebvIL-10 (A), its frameshift (A), and cIL-10 (B) analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In the ebvIL-10/CGT gene, the rare AGG codon at Arg159 was substituted with a frequently used arginine CGU codon. IPTG was added into culture for the induction of protein expression at OD600 = 0.6, and cells had been grown for three additional hours.

The frameshift was also avoided by enhancing the level of rare tRNAs. ebvIL-10 was expressed in a BL21 (DE3) derivative, Rosetta2 (DE3) strain, which carries a plasmid that expresses tRNAs decoding seven rare codons (AGG, AGA, AUA, CUA, GGA, CCC, and CGG) [23]. The tRNA level increase did not only prevent the frameshift but also improved the expression level and purity of ebvIL-10, as observed for AGG codon substitution with CGU codon (Fig. 4A). In contrast, cIL-10 showed essentially identical expression levels in strains Rosetta2 (DE3) and BL21 (DE3) (Fig. 4B). Codon optimization of the cIL-10 gene had no effect on cIL-10 expression levels in E. coli [24].

Discussion

Mass spectrometry analysis of ebvIL-10M1NTH and its frameshift, combined with gel filtration analysis of monomeric cIL-10/ebvIL-10 chimeras, provides strong evidence that the rare AGG codon at ebvIL-10 Arg159 is responsible for a +1 frameshift during ebvIL-10 expression. The argument is strengthened by our results that the frameshift could be prevented by substituting the rare AGG codon with a frequent one (CGU). The involvement of the rare AGG codon in the frameshift can be explained by correlation between codon usage and the abundance of cognate tRNA in E. coli [22]. The AGG codon is used as an extremely low frequency of 3–9×10−5, and the fraction of its cognate tRNA is only 0.65% out of total tRNA. This leads to ribosome stalling at the rare AGG codon due to a limited tRNA supply, resulting in translational errors. It is well documented that a tandem AGG codon repeat yields a 50% +1 frameshift and that the number of the rare codons is proportional to the frameshift frequency [25]. However, the ebvIL-10 mRNA has only one rare AGG codon at and near the frameshift site. Interestingly, the AGG codon is followed by the most inefficient stop signal, UGAC (Fig. 3B) [26]. Considering the environment of the AGG codon in ebvIL-10 mRNA, the AGG codon and the UGAC stop signal located next to each other are proposed to act like a tandem rare codon repeat in the context of translational rates. Ribosomes would stall at the sequence of 5′-AGGUGAC-3′, and shift to a frequently used glycine codon, GGU, as a frequency of ~10–20% (Fig. 2 and 4A).

The frameshift protein that contains essentially all the residues of ebvIL-10 plus a 4 kDa peptide extension shares numerous biophysical properties with ebvIL-10. Thus, it is difficult to completely purify ebvIL-10 from its frameshift by ion exchange and gel filtration chromatographies. Sample heterogeneity can impede crystallization and introduce inaccuracy in biophysical analysis. Therefore, the improvement of ebvIL-10 purity by the frameshift prevention has been essential for X-ray and binding analyses [13]. Moreover, the increase in ebvIL-10 expression yields has benefited ongoing NMR studies that require large amount of labeled sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter E. Prevelige, Jr. and Sebyung Kang for help with the mass spectrometry analysis. This research was supported by NIH grant AI047300 to M.R.W.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, Roncarolo MG, te Velde A, Figdor C, Johnson K, Kastelein R, Yssel H, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacNeil IA, Suda T, Moore KW, Mosmann TR, Zlotnik A. IL-10, a novel growth cofactor for mature and immature T cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:4167–4173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira P, de Waal-Malefyt R, Dang MN, Johnson KE, Kastelein R, Fiorentino DF, deVries JE, Roncarolo MG, Mosmann TR, Moore KW. Isolation and expression of human cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor cDNA clones: homology to Epstein-Barr virus open reading frame BCRFI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1172–1176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding Y, Qin L, Kotenko SV, Pestka S, Bromberg JS. A single amino acid determines the immunostimulatory activity of interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 2000;191:213–224. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding Y, Qin L, Zamarin D, Kotenko SV, Pestka S, Moore KW, Bromberg JS. Differential IL-10R1 expression plays a critical role in IL-10-mediated immune regulation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6884–6892. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zdanov A, Schalk-Hihi C, Menon S, Moore KW, Wlodawer A. Crystal structure of Epstein-Barr virus protein BCRF1, a homolog of cellular interleukin-10. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:460–467. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zdanov A, Schalk-Hihi C, Gustchina A, Tsang M, Weatherbee J, Wlodawer A. Crystal structure of interleukin-10 reveals the functional dimer with an unexpected topological similarity to interferon gamma. Structure. 1995;3:591–601. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter MR, Nagabhushan TL. Crystal structure of interleukin 10 reveals an interferon gamma-like fold. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12118–12125. doi: 10.1021/bi00038a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan JC, Braun S, Rong H, DiGiacomo R, Dolphin E, Baldwin S, Narula SK, Zavodny PJ, Chou CC. Characterization of recombinant extracellular domain of human interleukin-10 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12906–12911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Josephson K, DiGiacomo R, Indelicato SR, Iyo AH, Nagabhushan TL, Parker MH, Walter MR. Design and analysis of an engineered human interleukin-10 monomer. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13552–13557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon SI, Jones BC, Logsdon NJ, Walter MR. Same structure, different function crystal structure of the Epstein-Barr virus IL-10 bound to the soluble IL-10R1 chain. Structure. 2005;13:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon SI, Logsdon NJ, Sheikh F, Donnelly RP, Walter MR. Conformational changes mediate interleukin-10 receptor 2 (IL-10R2) binding to IL-10 and assembly of the signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35088–35096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josephson K, Jones BC, Walter LJ, DiGiacomo R, Indelicato SR, Walter MR. Noncompetitive antibody neutralization of IL-10 revealed by protein engineering and x-ray crystallography. Structure. 2002;10:981–987. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00791-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logsdon NJ, Jones BC, Josephson K, Cook J, Walter MR. Comparison of interleukin-22 and interleukin-10 soluble receptor complexes. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:1099–1112. doi: 10.1089/10799900260442520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:741–768. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurland C, Gallant J. Errors of heterologous protein expression. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7:489–493. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seetharam R, Heeren RA, Wong EY, Braford SR, Klein BK, Aykent S, Kotts CE, Mathis KJ, Bishop BF, Jennings MJ, Smith CE, Siegel NR. Mistranslation in IGF-1 during over-expression of the protein in Escherichia coli using a synthetic gene containing low frequency codons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;155:518–523. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kane JF, Violand BN, Curran DF, Staten NR, Duffin KL, Bogosian G. Novel in-frame two codon translational hop during synthesis of bovine placental lactogen in a recombinant strain of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6707–6712. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg AH, Goldman E, Dunn JJ, Studier FW, Zubay G. Effects of consecutive AGG codons on translation in Escherichia coli, demonstrated with a versatile codon test system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:716–722. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.716-722.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong H, Nilsson L, Kurland CG. Co-variation of tRNA abundance and codon usage in Escherichia coli at different growth rates. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:649–663. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novy R, Drott D, Yaeger K, Mierendorf R. Overcoming the codon bias of E. coli for enhanced protein expression. inNovations. 2001;12:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W, Xiao W, Wei H, Zhang J, Tian Z. mRNA secondary structure at start AUG codon is a key limiting factor for human protein expression in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spanjaard RA, van Duin J. Translation of the sequence AGG-AGG yields 50% ribosomal frameshift. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7967–7971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tate WP, Mannering SA. Three, four or more: the translational stop signal at length. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:213–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6391352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]