Abstract

Psoriasis vulgaris is a common and chronic inflammatory skin disease which has the potential to significantly reduce the quality of life in severely affected patients. The incidence of psoriasis in Western industrialized countries ranges from 1.5 to 2%. Despite the large variety of treatment options available, patient surveys have revealed insufficient satisfaction with the efficacy of available treatments and a high rate of medication non-compliance. To optimize the treatment of psoriasis in Germany, the Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft and the Berufsverband Deutscher Dermatologen (BVDD) have initiated a project to develop evidence-based guidelines for the management of psoriasis. The guidelines focus on induction therapy in cases of mild, moderate, and severe plaque-type psoriasis in adults. The short version of the guidelines reported here consist of a series of therapeutic recommendations that are based on a systematic literature search and subsequent discussion with experts in the field; they have been approved by a team of dermatology experts. In addition to the therapeutic recommendations provided in this short version, the full version of the guidelines includes information on contraindications, adverse events, drug interactions, practicality, and costs as well as detailed information on how best to apply the treatments described (for full version, please see Nast et al., JDDG, Suppl 2:S1–S126, 2006; or http://www.psoriasis-leitlinie.de).

Keywords: Evidence-based guidelines, Psoriasis vulgaris, Treatment

Introduction

The Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG) and the Berufsverband Deutscher Dermatologen (BVDD) have initiated a project to develop evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The full version of the Guidelines has been published in the Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft (JDDG 2006 Suppl 2) and is available at http://www.psoriasis-leitlinie.de [149]. This article summarizes the key points of the Guidelines.

Background

Psoriasis vulgaris is a common and chronic inflammatory skin disease which has the potential to significantly reduce the quality of life in severely affected patients. The incidence of psoriasis in Western industrialized countries is 1.5–2% [2]. Studies on the impairment of life quality have shown that, depending on the severity of the disease, a significant burden may exist in the form of a disability or psychosocial stigmatization [3]. Patient surveys have shown that the mental and physical impairment associated with psoriasis is comparable to that of other significant chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes or chronic respiratory diseases [4].

Patient surveys have shown that only 25% of psoriasis patients are highly satisfied with the outcome of their treatment, another 50% indicate moderate satisfaction, and approximately 20% report low treatment satisfaction [5]. In addition, there is a high non-compliance rate in the intake of medication of up to 40% [1].

Experience has shown that treatment selection for patients with psoriasis vulgaris is more commonly based on traditional concepts than on evidence-based data on the efficacy of various therapeutic options. In addition, it appears that systemic therapies are occasionally not applied in situations where they are needed due to the increased effort involved in monitoring the patients for unwanted side effects and possible interactions with other drugs.

Goal of the Guidelines

The overall objective of the Guidelines is to provide dermatologists in clinics and private practice with an accepted and evidence-based decision-making tool for the selection and implementation of a suitable and efficacious treatment for patients with psoriasis vulgaris. The focus of the Guidelines is on the induction therapy of mild, moderate, and severe plaque-type psoriasis in adults.

Physicians’ personal experiences and traditional therapeutic concepts should be supplemented and, if necessary, replaced by an evidence-based assessment of the efficacy of individual therapies in psoriasis vulgaris.

The guidelines provide in-depth explanations of the available systemic and topical treatments for psoriasis, including the different photo- and photochemical therapies, and provide detailed descriptions of the administration and safety aspects.

By providing background information on the profile of the available drugs, including efficacy, safety, and aspects of practicality and costs, the Guidelines should facilitate the process of selecting an appropriate treatment for each individual patient. This should help increase compliance and optimize the benefit/risk ratio of psoriasis therapies.

Methods

A detailed description of the methodology employed in developing the Guidelines can be found in the Method Report on the Guidelines (http://www.psoriasis-leitlinie.de).

Basis of data

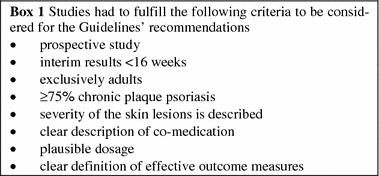

A systematic search of the literature was carried out in May 2005 with the objective of assessing the effectiveness of individual therapeutic options. This search yielded 6,224 publications of which 142 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for the Guidelines (see Box 1) and were therefore included in the assessment of the effectiveness of the relevant treatment. Various other aspects were evaluated on the basis of information presented in available literature, without a systematic analysis, and the years of personal experience of the experts.

Evidence assessment

The efficacy and effectiveness of each intervention was evaluated using evidence-based criteria.

The methodological quality of each individual study was assessed using the following grades of evidence (GE):

- A1

Meta-analysis that includes at least one randomized study with grade A2 evidence. In addition, the results of the different studies included in the meta-analysis must be consistent with one another.

- A2

A high-quality (e.g. sample-size calculation, flow chart, intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, sufficient size) randomized, double-blind comparative clinical study.

- B

Randomized clinical study of lesser quality or other comparative study (non-randomized, cohort, or case-control study).

- C

Non-comparative study.

- D

Expert opinion.

Individual interventions (i.e., as monotherapy) were rated according to the following levels of evidence (LE):

Intervention is supported by studies with grade A1 evidence or studies with grade A2 evidence whose results are predominantly consistent with one another.

Intervention is supported by studies with grade A2 evidence or studies with grade B evidence whose results are predominantly consistent with one another.

Intervention is supported by studies with grade B evidence or studies with grade C evidence whose results are predominantly consistent with one another.

Little or no systematic empirical evidence

Therapeutic recommendation

A distinct rating of the therapeutic options or a strict clinical algorithm cannot be defined for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. The criteria for selecting a particular therapy are complex. The decision for a specific treatment should be based on the profile of the available drugs and the characteristics of a given patient. The decision for or against a therapy remains a case-by-case decision. These Guidelines provide a reasonable form of assistance in deciding on a suitable therapy and are an instrument for optimizing the required therapeutic process.

The recommendations formulated in the text are supported graphically in selected key recommendations by the following indications of the strength of the therapeutic recommendation:

- ↑↑

Measure is highly recommended

- ↑

Measure is recommended

- →

Neutral

- ↓

Measure is not recommended

- ↓↓

Measure is highly inadvisable

The strength of the recommendation reflects both a treatment’s efficacy and the level of evidence supporting it as well as aspects of safety, practicality, and the cost/benefit ratio. A consensus on the strength of the recommendation was reached during the Consensus Conference.

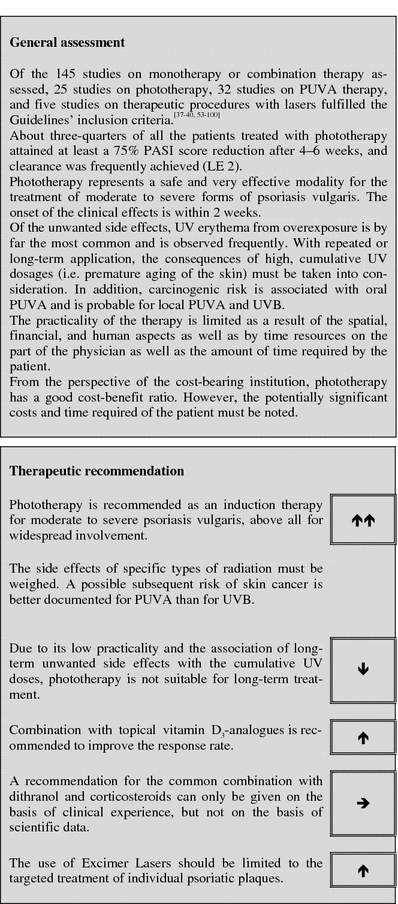

Results

Therapeutic options are named and discussed in alphabetical order.

Therapeutic strategies

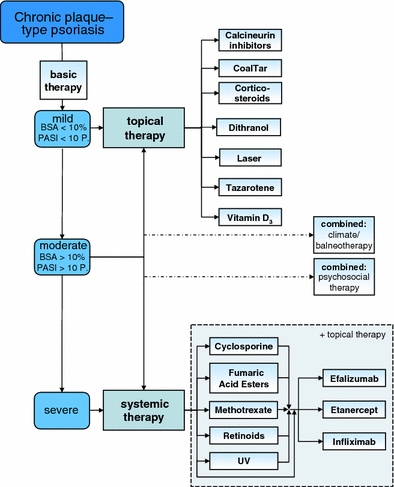

Fig. 1.

Overview of the therapeutic options evaluated for chronic plaque psoriasis (the therapeutic options are listed alphabetically and do not represent a ranking)

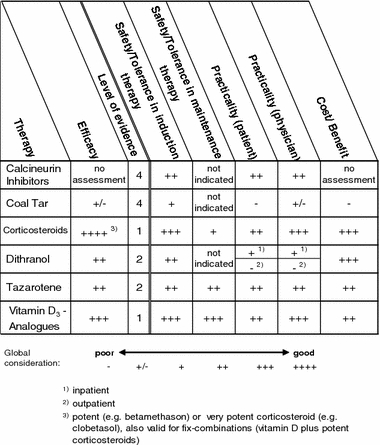

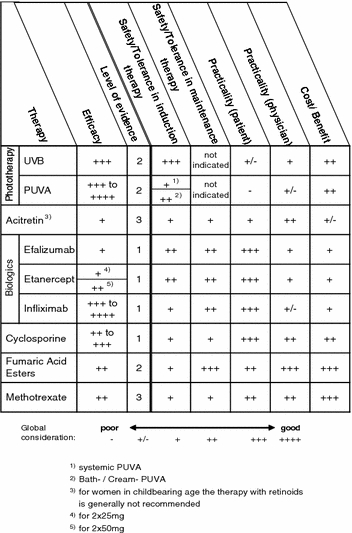

Evaluation of topical and systemic therapies in tabular form

These tables are intended to provide a rough orientation for evaluating the therapeutic options. Cumulative calculations of the individual aspects for the overall evaluation of the therapeutic options are not possible and cannot be drawn upon for the final analysis of a therapeutic option. The product assessment for each individual patient may deviate greatly. A direct comparison between systemic and topical therapies is not possible because of the different severity of the psoriasis lesions of patients treated with topical or systemic treatments. The evaluations reported here were made on the basis of data extracted from the literature and expert opinions.

For further details refer to the Methods Report at www.psoriasis-leitlinie.de

Topical monotherapy

Phototherapy and systemic monotherapy

(a) Efficacy The evaluation of the efficacy column reflects the percentage of patients who achieved a reduction in the baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) of ≥75%.

| Scale | Systemic therapy | Topical therapy |

|---|---|---|

| ++++ | Approx. 90% | Approx. 60% |

| +++ | Approx. 70% | Approx. 45% |

| ++ | Approx. 50% | Approx. 30% |

| + | Approx. 30% | Approx. 15% |

| +/− | Approx. 10% | Approx. 5% |

| – | Not defined | Not defined |

The evidence level applies only to the estimate of efficacy.

(b) Safety/tolerance in induction therapy or maintenance therapy This refers to the risk of occurrence of severe adverse drug reactions or the probability of adverse drug reactions that would result in the discontinuation of therapy.

(c) Practicality (Patient) This evaluation analyzes the effort involved in handling and administrating the treatment regimen by the patient.

(d) Practicality (Physician) This aspect considers the amount of work (documentation, explanation, monitoring), personnel and equipment needs, time for physician/patient interaction, remuneration of therapeutic measures, invoicing difficulties/risk of recourse claims from the health insurance companies.

(e) Cost/benefit Consideration of the costs of an induction therapy or a maintenance therapy.

The evaluations of safety/tolerance in induction therapy or maintenance therapy as well as practicality for the physician or patient and the cost/benefit were performed using a scale ranging from poor (–) to good (++++). The gradation between these two extremes was made based on expert opinion and unsystematic literature search. A level of evidence was not given for these evaluations since no systematic literature review was performed.

Evaluation of topical therapies

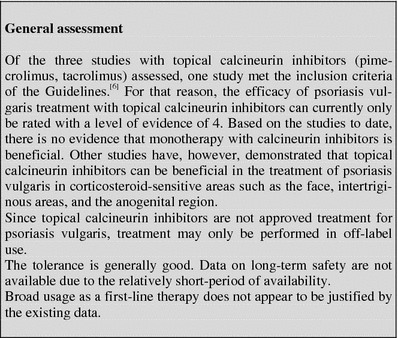

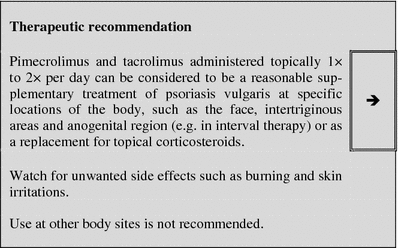

Calcineurin inhibitors

Table 1.

Tabular summary

| Calcineurin inhibitors | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | |

| Pimecrolimus (Elidel®) | 2002 (Atopic dermatitis, not approved for psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Tacrolimus (Protopic®) | 2002 (Atopic dermatitis, not approved for psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended initial dosage | Pimecrolimus cream: 1× to 2× daily Tacrolimus: 1× to 2× daily (application on the face: Begin with 0.03% salve; increase later dosage to 0.1% salve) |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Individual therapeutic adjustment |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After approximately 2 weeks |

| Response rate | No data available |

| Important contraindications | Pregnancy and nursing (due to lack of experience) skin infections, immune suppression |

| Important adverse drug reactions (ADRs) | Burning sensation on skin, skin infections |

| Important drug interactions | None known |

| Other | Cave: Do not combine with phototherapy! Photoprotection! |

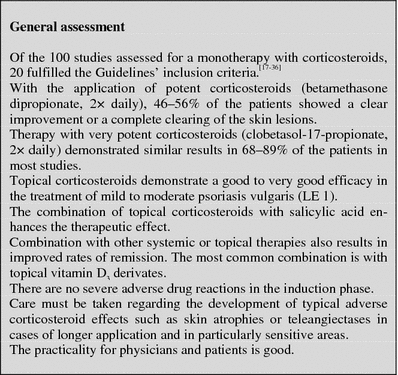

Corticosteroids

Table 2.

Tabular summary

| Corticosteroids | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 1956 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | None |

| Recommended initial dosage | One to two times daily |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Gradual reduction following onset of effect |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 1–2 weeks |

| Response rate | Betamethasone dipropionate, two times daily: marked improvement or clearance of the skin lesions in 46–56% patients after 4 weeks (LE 1) |

| Important contraindications | Skin infections, rosacea, perioral dermatitis |

| Important ADRs | Skin infections, perioral dermatitis, skin atrophy, hypertrichosis, striae |

| Important drug interactions | None |

| Other | – |

Coal tar

Table 3.

Tabular summary

| Coal tar | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | Listed active ingredient since 2000 (DAC on page 170), historical application, various tar-containing externals are licensed as drugs, application of tar as anti-psoriatic following publication by Goeckermann in 1925 |

| Recommended control parameters | After long-term application/application on large areas: if needed clinical controls for potential development of skin carcinoma |

| Recommended initial dosage | 5–20% salve preparations or gels for local therapy, 1× daily |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | No long-term application (max. 4 weeks, DAC 2000) |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 4–8 weeks, efficacy improves in combination with UV application |

| Response rate | There is insufficient data available on the response rate as a monotherapy (LE 4) |

| Important contraindications | Pregnancy and nursing |

| Important ADRs | Color, odor, carcinogenic risk, phototoxicity—which is part of the desired effect |

| Important drug interactions | Not known with topical use |

| Other | DAC 2000 (on page 170), Hazardous Goods Directive Appendix 4 No. 13 |

Dithranol

Table 4.

Tabular summary

| Dithranol | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | |

| Psoralon | 1983 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Psoradexan | 1994 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Micanol | 1997 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Intensity of irritation |

| Recommended initial dosage | Begin with 0.5% preparation for long-term therapy or 1% for short-contact therapy, then increase if tolerated |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Not recommended for maintenance therapy |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 2–3 weeks |

| Response rate | Marked improvement or clearance of skin lesions in 30–50% of the patients (LE 2) |

| Important contraindications | Acute, erythrodermic forms of psoriasis vulgaris; pustular psoriasis |

| Important ADRs | Burning and reddening of the skin in >10% |

| Important drug interactions | – |

| Other | – |

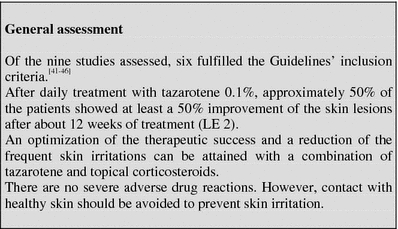

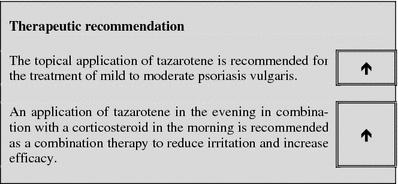

Tazarotene

Table 5.

Tabular summary

| Tazarotene | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 1997 (psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Check development of skin irritations |

| Recommended initial dosage | Begin with one treatment daily of tazarotene gel 0.05% in the evening for approximately 1–2 weeks |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | If necessary continue for 1–2 weeks with tazarotene gel 0.1% |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 1–2 weeks |

| Response rate | After 12 weeks therapy with 0.1% tazarotene gel improved findings of at least 50% in approximately 50% of the patients (LE 2) |

| Important contraindications | Pregnancy, nursing |

| Important ADRs | Pruritus, burning sensation of skin, erythema, irritation |

| Important drug interactions | Avoid concomitant use of preparations with irritating and drying properties |

| Other | – |

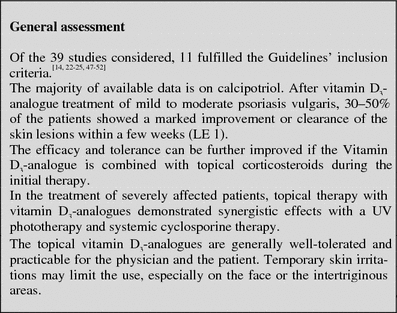

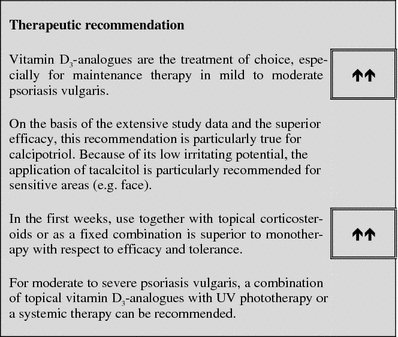

Vitamin D3 and analogues

Table 6.

Tabular summary

| Vitamin D3 and analogues | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | |

| Calcipotriol | 1992 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Tacalcitol | 1994 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Calcitriol | 1999 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Calcipotriol/Betamethasone | 2002 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Monitor for skin irritations |

| Recommended initial dosage | Calcipotriol: 1× to 2× daily to affected locations, up to a maximum of 30% of the body surface |

| Tacalcitol: 1× daily to affected locations, up to a maximum of 20% of the body surface | |

| Calcitriol: 2× daily to affected locations, up to a maximum of 35% of the body surface | |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Calcipotriol: 1× to 2× daily, up to 100 g/week for up to 1 year |

| Tacalcitol: 1× daily for 8 weeks, for up to 18 months, on a maximum of 15% of the body surface with up to 3.5 g daily | |

| Calcitriol: insufficient experience with the application for more than 6 weeks | |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 1–2 weeks |

| Response rate | Between 30 and 50% of the patients demonstrated a marked improvement or clearance of the lesions after 4–6 weeks (LE 1) |

| Important contraindications | Diseases with abnormal calcium metabolism, severe liver and renal diseases |

| Important ADRs | Skin irritation (reddening, itching, burning) |

| Important drug interactions | Drugs which elevate the calcium levels, (e.g. thiazide diuretics), no concomitant application of topical salicylic acid preparations (inactivation) |

| Other | Exposure to UV light results in inactivation of the vitamin D3-analogues |

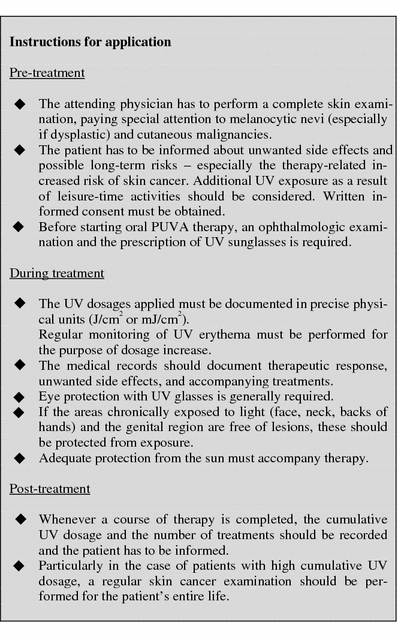

Phototherapy

Table 7.

Tabular summary

| Phototherapy | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | Clinical experience, depending on the modality for >50 years |

| Recommended control parameters | Regular skin inspection (UV erythema) |

| Recommended initial dosage | Individual dose depends on skin type; options: |

| • UVB: 70% of minimum erythema dose (MED) | |

| • Oral PUVA (photochemotherapy): 75% of the minimum phototoxic dose (MPD) | |

| • Bath/cream PUVA: 20–30% of MPD | |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Increase according to degree of UV erythema |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 1–2 weeks |

| Response rate | In >75% of the patients PASI, 75 after 4–6 weeks (LE 2) |

| Important contraindications | Photo-dermatoses/photosensitive diseases, skin malignancies, immunosuppression Only PUVA: pregnancy and nursing |

| Important ADRs | Erythema, itching, blistering, malignancies Only oral PUVA: nausea |

| Important drug interactions | Drugs causing phototoxicity or photoallergy |

| Other | Combination with topical preparations acts synergistically, PUVA may not be combined with cyclosporine |

Evaluation of systemic therapies

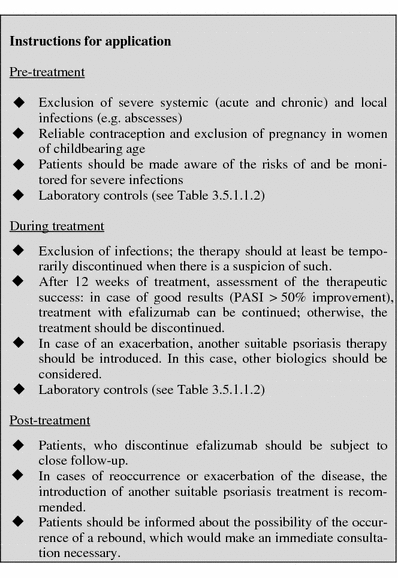

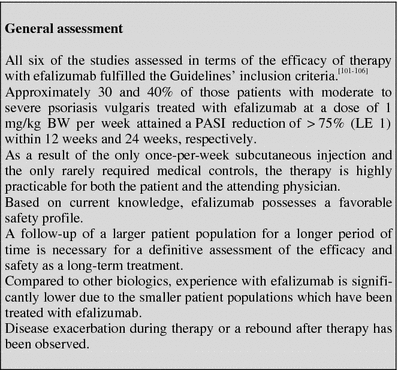

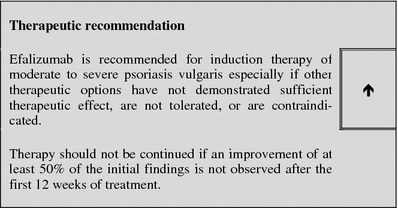

Efalizumab

Table 8.

Tabular summary

| Efalizumab | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | September 2004 (psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Prior to therapy exclusion of significant infections, complete blood count, liver values |

| Recommended initial dosage | 0.7 mg/kg body weight (BW) per week |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | 1 mg/kg BW per week |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 4–8 weeks |

| Response rate | PASI 75 for approximately 30% of the patients after 12 weeks (LE 1) |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Chronic or acute infections, pregnancy, malignant diseases, immune deficiencies, no vaccinations before or during treatment |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Flu-like injection reactions, leukocytosis and lymphocytosis, rebound, exacerbation and arthralgia, thrombocytopenia |

| Important drug interactions | Not known |

| Other | Stop therapy due to the risk of exacerbation and rebound if a PASI reduction of 50% is not achieved after 12 weeks |

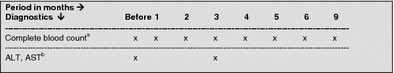

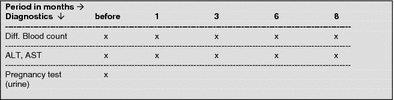

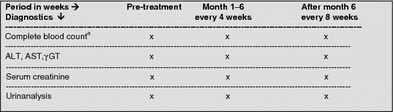

Table 9.

Laboratory controls during treatment with efalizumab

aHb (hemoglobin), HCT (hematocrit), erythrocytes, leukocytes, differential blood count, platelets

bALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase

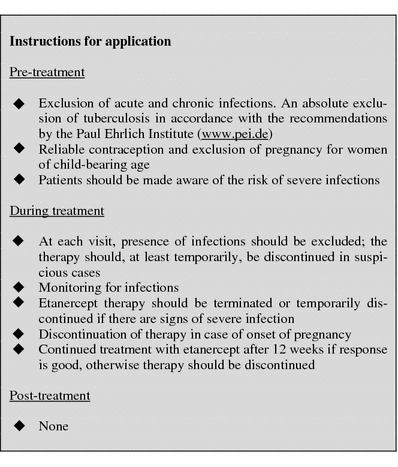

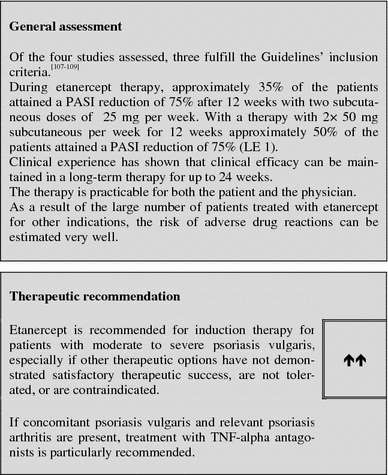

Etanercept

Table 10.

Tabular summary

| Etanercept | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 2002 (Psoriasis arthritis )/2004 (psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Prior to therapy exclusion of tuberculosis, complete blood count, liver and renal values, urinanalysis |

| Recommended initial dosage | Twice 25 mg per week or 2× 50 mg/week |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Twice 25 mg per week |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 4–8 weeks, at the latest after 12 weeks |

| Response rate | PASI 75 in 34% (2 × 25 mg) or 49% (2 × 50 mg) of the patients at the end of the induction phase (12 weeks) (LE 1) |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Infections, pregnancy, nursing, heart failure NYHA III–IV |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Local reactions, infections |

| Important drug interactions (limited selection) | Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) |

| Other | – |

Table 11.

Laboratory controls during treatment with etanercept

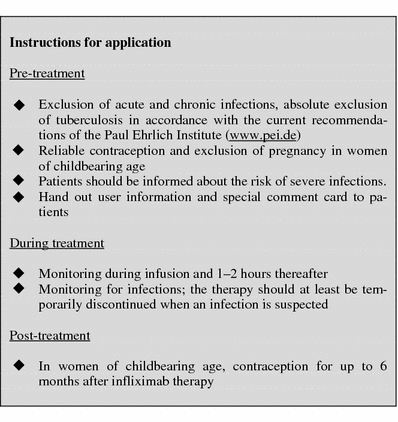

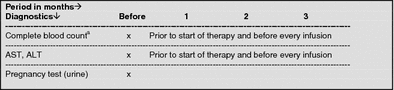

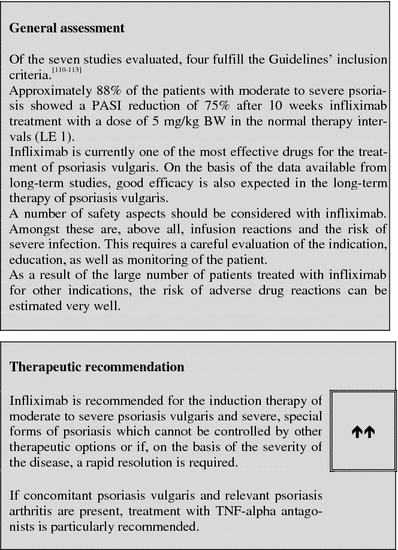

Infliximab

Table 12.

Tabular summary

| Infliximab | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 2004 (Psoriasis arthritis)/2005 (psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Prior to therapy exclusion of tuberculosis, during therapy: leukocyte and platelet counts, liver value controls, signs of clinical infection |

| Recommended initial dosage | 5 mg/kg BW at week 0, 2, 6 |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | 5 mg/kg BW in dosage intervals of 8 weeks |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 1–2 weeks |

| Response rate | PASI 75 in ≥80% of the patients with moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris (LE 1) |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Acute or chronic infections, tuberculosis, cardiac failure NYHA III–IV, pregnancy and nursing |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Infusion reactions, severe infections, progression of heart failure NYHA III–IV, very rare liver failure, autoimmune phenomena |

| Important drug interactions (limited selection) | Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) |

| Other | – |

Table 13.

Laboratory controls during treatment with infliximab

aHb, HCT, erythrocytes, leukocytes, differential blood count, platelets

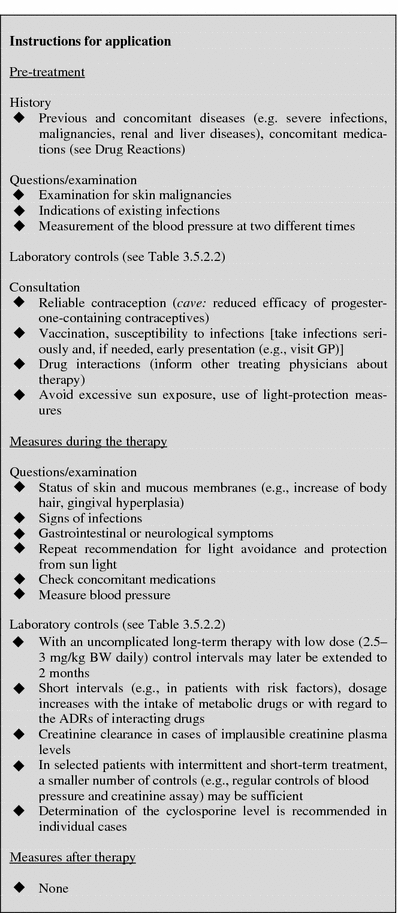

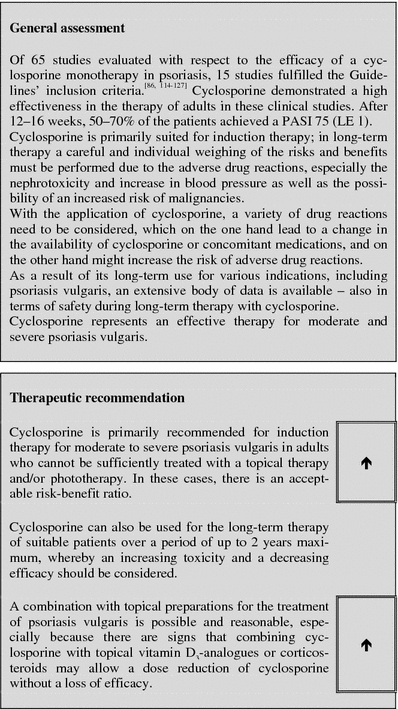

Cyclosporine

Table 14.

Tabular summary

| Cyclosporine | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 1983 (Transplantation medicine) |

| 1993 (Psoriasis vulgaris) | |

| Recommended control parameters | Interview/examination: |

| • Status of skin and mucous membranes | |

| • Signs of infection | |

| • Neurological, gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| • Blood pressure | |

| Laboratory controls: see Table 14 | |

| Recommended initial dosage | 2.5–3 (max. 5) mg/kg BW |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Interval therapy (between 8 and 16 weeks) with dosage reduction at the end of the induction therapy (e.g., 0.5 mg/kg BW every 14 days) or |

| Continuous long-term therapy with dosage reduction (e.g. by 50 mg every 4 weeks after week 12) and a dosage increase by 50 mg with relapse | |

| Maximum total duration of therapy: 2 years | |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After approximately 4 weeks |

| Response rate | Dose-dependent: after 8–16 weeks with 3 mg/kg BW; PASI 90 in approximately 30–50% of patient and PASI 75 in approximately 50–70% of patients (LE 1) |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Absolute: |

| Reduced renal function, insufficiently controlled arterial hypertension, uncontrolled infections, relevant malignancies (current or previous, in particular hematologic diseases and cutaneous malignancies with the exception of basal cell carcinoma) | |

| Relative: | |

| Relevant hepatic dysfunction, pregnancy and nursing, concomitant use of substance which interacts with cyclosporine, concomitant UV-therapy or prior PUVA-pre-therapy with cumulative dosage >1000 J/cm², concomitant application of other immunosuppressives, retinoids or long-term prior-therapy with methotrexate (MTX) | |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Renal failure, increase of blood pressure, liver failure, nausea, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, hypertrichosis, gingival hyperplasia, tremor, weariness, parasthesia, hyperlipidemia |

| Important drug interactions (limited selection) | Increase of the cyclosporine level (CYP3A inhibition) through: |

| Allopurinol, calcium antagonists, amiodarone, antibiotics (macrolides, clarithromycin, josamycin, ponsinomycin, pristinamycin, doxycycline, gentamicin, tobramycin, ticarcillin, quinolones), ketoconazole, oral contraceptives, methylprednisolone (high dosages), ranitidine, cimetidine, grapefruit juice | |

| Decrease of the cyclosporine level (CYP3A induction) through: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, barbiturates, metamizole, St. John’s wort | |

| Possible reinforcement of nephrotoxic adverse drug reactions through: Aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, ciprofloxacin, acyclovir, non-steroidal antiphlogistics | |

| Specific interactions: | |

| Potassium-saving substances: increased risk of hyperpotassemia | |

| Reduced clearance of: Digoxin, colchicine, prednisolone, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (e.g. lovastatin), diclofenac | |

| Other | Increased risk of lympho-proliferative diseases in transplant patients. Increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma in psoriasis patients following excessive phototherapy. |

| Only moderately effective in and not approved for psoriatic arthritis | |

| Also used successfully in the therapy of chronic-inflammatory diseases in children | |

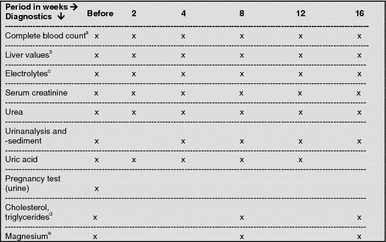

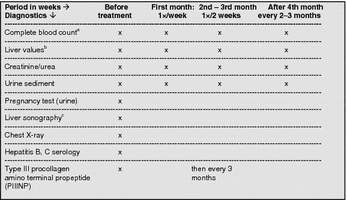

Table 15.

Laboratory controls during treatment with cyclosporine

aErythrocytes, leukocytes, platelets

bALT, AST, AP (alkaline phosphatase), γGT (gamma glutamyl transpeptidase), bilirubin

cSodium, potassium

dRecommended twice (fasting) and week-2 and 0

eOnly with indication (e.g. muscle cramps)

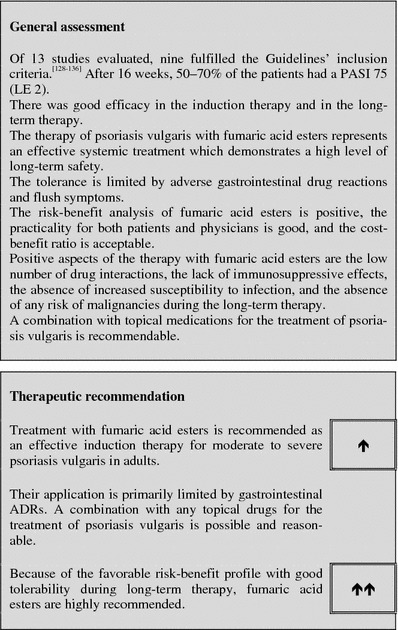

Fumaric acid esters

Table 16.

Tabular summary

| Fumaric acid esters | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 1995 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Serum creatinine, transaminases/γGT, complete blood count including differential blood count, urinanalysis |

| Recommended initial dosage | According to recommended dosage regimen see Table 17 |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Individually adapted dosage |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After approximately 6 weeks |

| Response rate | PASI 75 in 50–70% of the patients at the end of the induction phase after 16 weeks (LE 2) |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract and/or the kidneys and chronic diseases, which are accompanied by an impairment of the leukocyte count or functions, malignant diseases, pregnancy and nursing |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Gastrointestinal complaints, flush, lymphopenia, eosinophilia |

| Important drug interactions | None known |

| Other | – |

Table 17.

Dosage regimen for Fumaderm therapy

| Fumaderm initial | Fumaderm | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 1-0-0 | |

| Week 2 | 1-0-1 | |

| Week 3 | 1-1-1 | |

| Week 4 | 1-0-0 | |

| Week 5 | 1-0-1 | |

| Week 6 | 1-1-1 | |

| Week 7 | 2-1-1 | |

| Week 8 | 2-1-2 | |

| Week 9 | 2-2-2 |

Table 18.

Laboratory controls during treatment with fumaric acid esters

aLeukocytes, platelets, erythrocytes, differential blood count

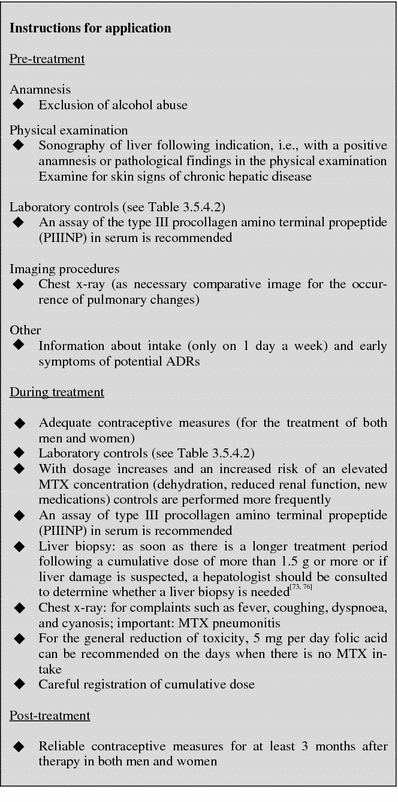

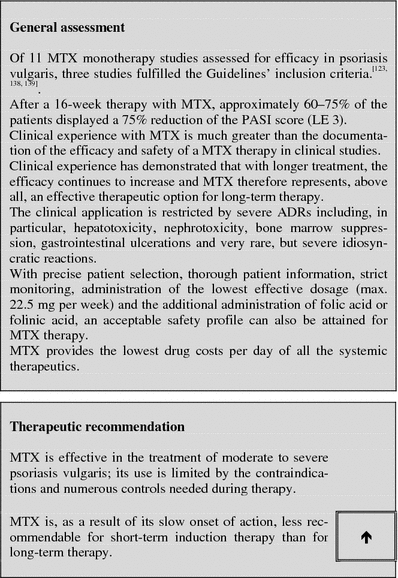

Methotrexate

Table 19.

Tabular summary

| Methotrexate | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | |

| Lantarel® | 1991 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Metex® 7.5/10 mg | 1992 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Metex® 2.5 mg | 2004 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Complete blood count (Hb, HCT, differential blood count, platelets), renal function (serum creatinine, urea, urine sediment), liver values (serum transaminases), III-procollagen amino terminal propeptides |

| Recommended initial dosage | 5–15 mg per week |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | 5–22.5 mg per week depending on effect |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 4–8 weeks |

| Response rate | PASI 75 in approximately 60% of the patients at the end of the induction phase of 16 weeks (LE 3) |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Absolute contraindications: |

| Desire to have children (for both men and women), pregnancy and nursing, inadequate contraception, drug consumption, alcoholism, known sensitivity to active ingredient methotrexate (e.g. pulmonary toxicity), bone marrow dysfunction, severe liver disease, severe infections, immunodeficiency, active peptic ulcers, hematologic changes (leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia), renal failure | |

| Relative contraindications: | |

| Kidney disorders, liver disorders, history of arsenic consumption , chronic congestive cardio-myopathy, adiposity, old age, diabetes mellitus, history of hepatitis, lack of patient compliance, ulcerative colitis, diarrhea, NSAID use, gastritis | |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Liver fibrosis/cirrhosis, pneumonia/alveolitis, bone marrow depression, renal damage, alopecia (reversible), nausea, weariness, vomiting, elevated transaminases, infection, gastrointestinal ulcerations, nephrotoxicity |

| Important drug interactions (limited selection) | Cyclosporine, salicylates, sulfonamides, probenecide, penicillin, colchicin, NSAIDs (naproxene, ibuprofene, etc.), ethanol, co-trimoxazole, pyrimethamine, chloramphenicol, sulfonamides, prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, cytostatics, probenecide, barbiturates, phenytoin, retinoids, sulfonamides, sulfonylurea, tetracyclines, co-trimoxazol, chloramphenicol, dipyridamole, retinoids, ethanol, leflunomide |

| Other | Consistent avoidance of alcohol, X-ray of the lungs prior to beginning therapy |

Table 20.

Laboratory controls during treatment with MTX [137]

aHb, HCT, erythrocytes, leukocytes, differential blood count, platelets

bALT, AST, AP, γGT, albumin, bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

cLiver biopsy instead of a liver sonography in risk groups

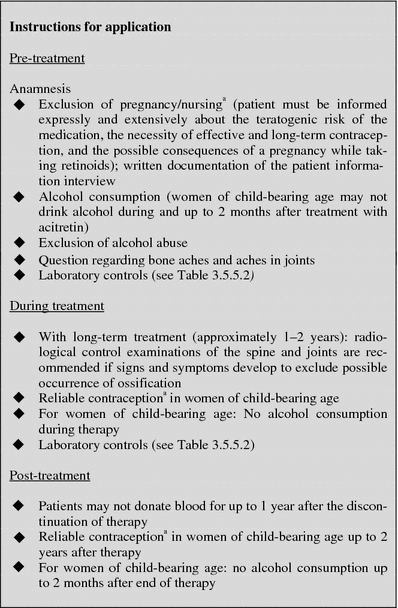

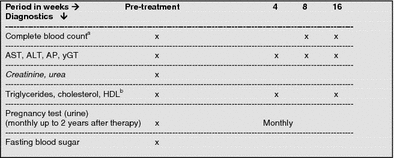

Retinoids

Table 21.

Tabular summary

| Acitretin | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | 1992 (Psoriasis vulgaris) |

| Recommended control parameters | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood count, liver values, renal values, blood lipid values, pregnancy test, x-ray control of the bones in case of long-term therapy |

| Recommended initial dosage | 0.3–0.5 mg/kg BW per day for approximately 4 weeks, then 0.5–0.8 mg/kg BW |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Individual dosaging dependent on the results and tolerance |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | After 4–8 weeks |

| Response rate | Widely variable and dose-dependent, no definite statement possible, partial remission (PASI 75) in 25–75% of the patients (30–40 mg per day) (LE 3) in studies |

| Important contraindications (limited selection) | Renal and liver damage, desire to have children in female patients of child-bearing age, pregnancy, nursing, alcohol abuse, manifest diabetes mellitus, wearing of contact lenses, history of pancreatitis, hyperlipidemia requiring drug treatment |

| Important ADRs (limited selection) | Hypervitaminosis A (e.g., cheilitis, xerosis, nose-bleeding, alopecia, increased skin fragility) |

| Important drug interactions (limited selection) | Phenytoin, tetracyclines, methotrexate, alcohol, mini-pill |

| Other | Contraception up to 2 years after discontinuation in female patients of child-bearing age |

aDouble contraception is recommended (e.g., condom + pill; IUD/Nuva-Ring + pill; cave: no low-dosed progesterone preparations/mini-pills) during and up to 2 years after the end of therapy; effectiveness is reduced by acitretin

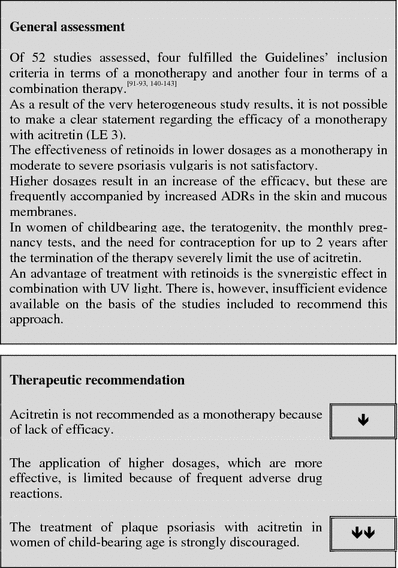

Table 22.

Laboratory controls during treatment with Acitretin

aHb, HCT, leukocytes, platelets

bPreferably assayed twice (week-2 and 0); HDL, high-density lipidoprotein

Other therapies

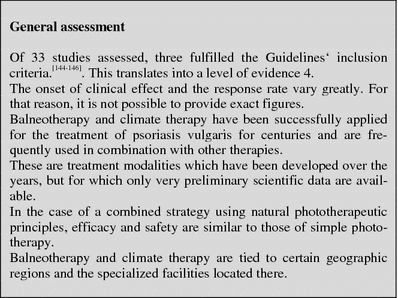

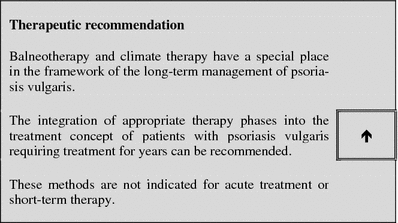

Climate/balneotherapy

Table 23.

Tabular summary

| Climate/balneotherapy | |

|---|---|

| First approved in Germany | Clinical experience with balneotherapy has existed for more than 200 years |

| Recommended control parameters | Regular skin inspection |

| Recommended initial dosage | Therapy regimens vary depending on the institution/location |

| Recommended maintenance dosage | Therapy regimens vary depending on the institution/location |

| Expected beginning of clinical effect | Varies greatly |

| Response rate | Varies greatly (LE 4) |

| Important contraindications | Dependent on modality selected |

| Important ADRs | Dependent on modality selected |

| Important drug interactions | Not applicable |

| Other | Balneotherapy and climate therapy are frequently combined |

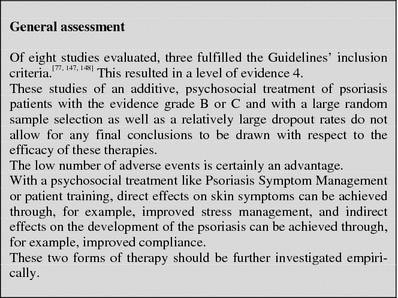

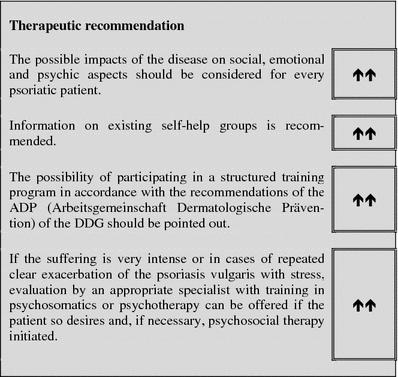

Psychosocial therapy

Notes on the use of the Guidelines

The presentation of the therapies deliberately focused on those aspects deemed particularly relevant by a panel of experts. Aspects which are not of specific importance for a certain intervention, but which are part of the physician’s general obligations to the patient, such as the investigation of intolerance and allergies toward certain drugs or the exclusion of contraindications, are not individually listed, but it is nevertheless taken for granted that these are part of the physician’s duty to provide care.

It is recommended that each and every user carefully reads and follows the product information and compare it with the recommendations in the Guidelines on dosaging, contraindications, and drug interactions for completeness and currentness. Every dose or application is administered at the user’s own risk. The authors and the publishers kindly request that users inform them of any inaccuracies that they might notice. The users are requested to keep themselves constantly informed of any new findings subsequent to the publication of the Guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The guidelines were generated upon request by the Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG) and the Berufsverband Deutscher Dermatologen (BVDD). The project was supported by the ‘Förderverein der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft’, the funding body of the DDG.

Conflicts of interests All authors have filled in specific forms to declare their conflicts of interests. These forms are available online under www.psoriasis-leitlinie.de. The experts involved in drawing up these guidelines received no payments for their work other than travel expenses.

Footnotes

With kind permission of Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft.

An enhanced version of these guidelines has been published with Blackwell in 2006.

References

- 1.Richards HL, Fortune DG, O’Sullivan TM, Main CJ, Griffiths CE (1999) Patients with psoriasis and their compliance with medication. J Am Acad Dermatol 41(4):581–583 [PubMed]

- 2.Nevitt GJ, Hutchinson PE (1996) Psoriasis in the community: prevalence, severity and patients’ beliefs and attitudes towards the disease. Br J Dermatol 135(4):533–537 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Schmid-Ott G, Malewski P, Kreiselmaier I, Mrowietz U (2005) Psychosoziale Folgen der Psoriasis—eine empirische Studie über die Krankheitslast bei 3753 Betroffenen. Hautarzt 56(5):466–472 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB Jr, Reboussin DM (1999) Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 41(3 Pt 1): 401–407 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, Margolis DJ, Rolstad T (2004) Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 9(2):136–139 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Carroll CL, Clarke J, Camacho F, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR (2005) Topical tacrolimus ointment combined with 6% salicylic acid gel for plaque psoriasis treatment. Arch Dermatol 141(1):43–46 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Agarwal R, Saraswat A, Kaur I, Katare OP, Kumar B (2002) A novel liposomal formulation of dithranol for psoriasis: preliminary results. J Dermatol 29(8):529–532 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Monastirli A, Georgiou S, Pasmatzi E, Sakkis T, Badavanis G, Drainas D, Sagriotis A, Tsambaos D (2002) Calcipotriol plus short-contact dithranol: a novel topical combination therapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 15(4):246–251 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gerritsen MJ, Boezeman JB, Elbers ME, van de Kerkhof PC (1998) Dithranol embedded in crystalline monoglycerides combined with phototherapy (UVB): a new approach in the treatment of psoriasis. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 11(3):133–139 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Prins M, Swinkels OQ, Van de Kerkhof PC, Van der Valk PG (2001) The impact of the frequency of short contact dithranol treatment. Eur J Dermatol 11(3):214–218 [PubMed]

- 11.Thune P, Brolund L (1992) Short- and long-contact therapy using a new dithranol formulation in individually adjusted dosages in the management of psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl 172:28–29 [PubMed]

- 12.De Mare S, Calis N, den Hartog G, van Erp PE, van de Kerkhof PC (1988) The relevance of salicylic acid in the treatment of plaque psoriasis with dithranol creams. Skin Pharmacol 1(4):259–264 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Prins M, Swinkels OQ, Bouwhuis S, de Gast MJ, Bouwman-Boer Y, van der Valk PG, van de Kerkhof PC (2000) Dithranol in a cream preparation: disperse or dissolve? Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 13(5):273–279 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hutchinson PE, Marks R, White J (2000) The efficacy, safety and tolerance of calcitriol 3 microg/g ointment in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a comparison with short-contact dithranol. Dermatology 201(2):139–145 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mahrle G, Schulze HJ (1990) The effect of initial external glucocorticoid administration on cignolin treatment of psoriasis. Z Hautkr 65(3):282, 285–287 [PubMed]

- 16.Agrup G, Agdell J (1985) A comparison between Antraderm stick (0.5% and 1%) and dithranol paste (0.125% and 0.25%) in the treatment of psoriasis. Br J Clin Pract 39(5):185–187 [PubMed]

- 17.Swinkels OQ, Prins M, Kucharekova M, de Boo T, Gerritsen MJ, van der Valk PG, van de Kerkhof PC (2002) Combining lesional short-contact dithranol therapy of psoriasis with a potent topical corticosteroid. Br J Dermatol 146(4):621–626 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Gottlieb AB, Ford R, Spellman MC (2003) The efficacy and tolerability of clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% in the treatment of mild to moderate plaque-type psoriasis of nonscalp regions. J Cutan Med Surg 7(3):185–192 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Chuang TY, Samson CR (1991) Clinical efficacy and safety of augmented betamethasone dipropionate ointment and diflorasone ointment for psoriasis—a multicentre, randomized, double-blinded study. J Dermatol Treat 2(2):63–66

- 20.Katz HI, Tanner DJ, Cuffie CA, Brody NI, Garcia CJ, Lowe NJ, Medansky RS, Roth HL, Shavin JS, Swinyer LJ (1998) A comparison of the efficacy and saftey of the combination mometasone furoate 0,1%/salicylic acid 5% ointment with each of its components in psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat 9(3):151–156

- 21.Koo J, Cuffie CA, Tanner DJ, Bressinck R, Cornell RC, DeVillez RL, Edwards L, Breneman DL, Piacquadio DJ, Guzzo CA, Monroe EW (1998) Mometasone furoate 0.1%–salicylic acid 5% ointment versus mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a multicenter study. Clin Ther 20(2):283–291 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Camarasa JM, Ortonne JP, Dubertret L (2003) Calcitriol shows greater persistence of treatment effect than betamethasone dipropionate in topical psoriasis therapy. J Dermatol Treat 14(1):8–13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Papp KA, Guenther L, Boyden B, Larsen FG, Harvima RJ, Guilhou JJ, Kaufmann R, Rogers S, van de Kerkhof PC, Hanssen LI, Tegner E, Burg G, Talbot D, Chu A (2003) Early onset of action and efficacy of a combination of calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 48(1):48–54 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Douglas WS, Poulin Y, Decroix J, Ortonne JP, Mrowietz U, Gulliver W, Krogstad AL, Larsen FG, Iglesias L, Buckley C, Bibby AJ (2002) A new calcipotriol/betamethasone formulation with rapid onset of action was superior to monotherapy with betamethasone dipropionate or calcipotriol in psoriasis vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol 82(2):131–135 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kaufmann R, Bibby AJ, Bissonnette R, Cambazard F, Chu AC, Decroix J, Douglas WS, Lowson D, Mascaro JM, Murphy GM, Stymne B (2002) A new calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate formulation (Daivobet) is an effective once-daily treatment for psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 205(4):389–393 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Stein LF, Sherr A, Solodkina G, Gottlieb AB, Chaudhari U (2001) Betamethasone valerate foam for treatment of nonscalp psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg 5(4):303–307 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Decroix J, Pres H, Tsankov N, Poncet M, Arsonnaud S (2004) Clobetasol propionate lotion in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Cutis 74(3):201–206 [PubMed]

- 28.Lebwohl M, Sherer D, Washenik K, Krueger GG, Menter A, Koo J, Feldman SR (2002) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of clobetasol propionate 0.05% foam in the treatment of nonscalp psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 41(5):269–274 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Peharda V, Gruber F, Prpic L, Kastelan M, Brajac I (2000) Comparison of mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment and betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol Croat 8(4):223–226

- 30.Shupack JL, Jondreau L, Kenny C, Stiller MJ (1993) Diflorasone diacetate ointment 0.05% versus betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in moderate-severe plaque-type psoriasis. Dermatology 186(2):129–132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Svensson ARI, Gisslen H, Nordin P, Gios I (1992) A comperative study of mometasone furoate oinment and betamethasone valerate ointment in patients with Psoriasis vulgaris. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 52(3):390–396 [DOI]

- 32.Weston WL, Fennessey PV, Morelli J, Schwab H, Mooney J, Samson C, Huff L, Harrison LM, Gotlin R (1988) Comparison of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression from superpotent topical steroids by standard endocrine function testing and gas chromatographic mass spectrometry. J Invest Dermatol 90(4):532–535 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Medansky RS, Cuffie CA, Tanner DJ (1997) Mometasone furoate 0.1%–salicylic acid 5% ointment twice daily versus fluocinonide 0.05% ointment twice daily in the management of patients with psoriasis. Clin Ther 19(4):701–709 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Housman TS, Keil KA, Mellen BG, McCarty MA, Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR (2003) The use of 0.25% zinc pyrithione spray does not enhance the efficacy of clobetasol propionate 0.05% foam in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 49(1):79–82 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Bagatell F (1988) Management of psoriasis: a clinical evaluation of the dermatological patch, Actidermregistered trade mark, over a topical steroid. Adv Ther 5(6):291–296

- 36.Fabry H, Yawalkar SJ (1983) A comparative multicentre trial of halometasone ointment and fluocortolone plus fluocortolone caproate ointment in the treatment of psoriasis. J Int Med Res 11(Suppl 1):26–30 [PubMed]

- 37.Belsito DV, Kechijian P (1982) The role of tar in Goeckerman therapy. Arch Dermatol 118(5): 319–321 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Diette KM, Momtaz K, Stern RS, Arndt KA, Parrish JA (1984) Role of ultraviolet A in phototherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 11(3):441–447 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.LeVine MJ, Parrish JA (1982) The effect of topical fluocinonide ointment on phototherapy of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 78(2):157–159 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Frost P, Horwitz SN, Caputo RV, Berger SM (1979) Tar gel-phototherapy for psoriasis. Combined therapy with suberythemogenic doses of fluorescent sunlamp ultraviolet radiation. Arch Dermatol 115(7):840–846 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Weinstein GD, Koo JY, Krueger GG, Lebwohl MG, Lowe NJ, Menter MA, Lew-Kaya DA, Sefton J, Gibson JR, Walker PS (2003) Tazarotene cream in the treatment of psoriasis: two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene creams 0.05% and 0.1% applied once daily for 12 weeks. J Am Acad Dermatol 48(5):760–767 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Gollnick H, Menter A (1999) Combination therapy with tazarotene plus a topical corticosteroid for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 140(Suppl 54):18–23 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Green L, Sadoff W (2002) A clinical evaluation of tazarotene 0.1% gel, with and without a high- or mid-high-potency corticosteroid, in patients with stable plaque psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg 6(2):95–102 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Koo JY, Martin D (2001) Investigator-masked comparison of tazarotene gel q.d. plus mometasone furoate cream q.d. vs. mometasone furoate cream b.i.d. in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 40(3):210–212 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Lebwohl M (2000) Strategies to optimize efficacy, duration of remission, and safety in the treatment of plaque psoriasis by using tazarotene in combination with a corticosteroid. J Am Acad Dermatol 43(2 Pt 3):S43–S46 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Poulin YP (1999) Tazarotene 0.1% gel in combination with mometasone furoate cream in plaque psoriasis: a photographic tracking study. Cutis 63(1):41–48 [PubMed]

- 47.Van de Kerkhof PC, Green C, Hamberg KJ, Hutchinson PE, Jensen JK, Kidson P, Kragballe K, Larsen FG, Munro CS, Tillman DM (2002) Safety and efficacy of combined high-dose treatment with calcipotriol ointment and solution in patients with psoriasis. Dermatology 204(3):214–221 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Guenther L, Van de Kerkhof PC, Snellman E, Kragballe K, Chu AC, Tegner E, Garcia-Diez A, Springborg J (2002) Efficacy and safety of a new combination of calcipotriol and betamethasone dipropionate (once or twice daily) compared to calcipotriol (twice daily) in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 147(2):316–323 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Kragballe K, Noerrelund KL, Lui H, Ortonne JP, Wozel G, Uurasmaa T, Fleming C, Estebaranz JL, Hanssen LI, Persson LM (2004) Efficacy of once-daily treatment regimens with calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate ointment and calcipotriol ointment in psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 150(6):1167–1173 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Ortonne JP, Kaufmann R, Lecha M, Goodfield M (2004) Efficacy of treatment with calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate followed by calcipotriol alone compared with tacalcitol for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: a randomised, double-blind trial. Dermatology 209(4):308–313 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Guenther LC, Poulin YP, Pariser DM (2000) A comparison of tazarotene 0.1% gel once daily plus mometasone furoate 0.1% cream once daily versus calcipotriene 0.005% ointment twice daily in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Clin Ther 22(10):1225–1238 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Lebwohl M, Yoles A, Lombardi K, Lou W (1998) Calcipotriene ointment and halobetasol ointment in the long-term treatment of psoriasis: effects on the duration of improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol 39(3):447–450 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Diette KM, Momtaz TK, Stern RS, Arndt KA, Parrish JA (1984) Psoralens and UV-A and UV-B twice weekly for the treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 120(9):1169–1173 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Ramsay CA, Schwartz BE, Lowson D, Papp K, Bolduc A, Gilbert M (2000) Calcipotriol cream combined with twice weekly broad-band UVB phototherapy: a safe, effective and UVB-sparing antipsoriatric combination treatment. The Canadian Calcipotriol and UVB Study Group. Dermatology 200(1):17–24 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Ring J, Kowalzick L, Christophers E, Schill WB, Schopf E, Stander M, Wolff HH, Altmeyer P (2001) Calcitriol 3 microg g-1 ointment in combination with ultraviolet B phototherapy for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results of a comparative study. Br J Dermatol 144(3):495–499 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Petrozzi JW (1983) Topical steroids and UV radiation in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 119(3):207–210 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Coven TR, Burack LH, Gilleaudeau R, Keogh M, Ozawa M, Krueger JG (1997) Narrowband UV-B produces superior clinical and histopathological resolution of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in patients compared with broadband UVB. Arch Dermatol 133:514–522 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Snellman E, Klimenko T, Rantanen T (2004) Randomized half-side comparison of narrowband UVB and trimethylpsoralen bath. Acta Derm Venereol 84(2):132–137 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Gordon PM, Diffey BL, Matthews JNS, Farr PM (1999) A randomised comparison of narrow-band TL-01 phototherapy and PUVA photochemotherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 41:728–732 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Leenutaphong V, Nimkulrat P, Sudtim S (2000) Comparison of phototherapy two times and four times a week with low doses of narrow-band ultraviolet B in Asian patients with psoriasis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 16(5):202–206 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Grundmann-Kollmann M, Ludwig R, Zollner TM, Ochsendorf F, Thaci D, Boehncke WH, Krutmann J, Kaufmann R, Podda M (2004) Narrowband UVB and cream psoralen-UVA combination therapy for plaque-type psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 50(5):734–739 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Katugampola GA, Rees AM, Lanigan SW (1995) Laser treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 133(6):909–913 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Housman TS, Pearce DJ, Feldman SR (2004) A maintenance protocol for psoriasis plaques cleared by the 308 nm excimer laser. J Dermatol Treat 15(2):94–97 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Trehan M, Taylor CR (2002) Medium-dose 308-nm excimer laser for the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 47(5):701–708 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Feldman SR, Mellen BG, Housman TS, Fitzpatrick RE, Geronemus RG, Friedman PM, Vasily DB, Morison WL (2002) Efficacy of the 308-nm excimer laser for treatment of psoriasis: results of a multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol 46(6):900–906 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB, Tannenbaum L, Pathak MA (1974) Photochemotherapy of psoriasis with oral methoxsalen and longwave ultraviolet light. N Engl J Med 291:1207–1211 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Kirby B, Buckley DA, Rogers S (1999) Large increments in psoralen-ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy are unsuitable for fair-skinned individuals with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 140(4):661–666 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Buckley DA, Healy E, Rogers S (1995) A comparison of twice-weekly MPD-PUVA and three times-weekly skin typing-PUVA regimens for the treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 133(3):417–422 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Berg M, Ros AM (1994) Treatment of psoriasis with psoralens and ultraviolet A. A double-blind comparison of 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 10:217–220 [PubMed]

- 70.Cooper EJ, Herd RM, Priestley GC, Hunter JA (2000) A comparison of bathwater and oral delivery of 8-methoxypsoralen in PUVA therapy for plaque psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol 25(2):111–114 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Collins P, Rogers S (1992) Bath-water compared with oral delivery of 8-methoxypsoralen PUVA therapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 127(4):392–395 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Calzavara-Pinton PG, Ortel B, Honigsmann H, Zane C, De Panfilis G (1994) Safety and effectiveness of an aggressive and individualized bath-PUVA regimen in the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatology 189(3):256–259 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Barth J, Dietz O, Heilmann S, Kadner H, Kraensel H, Meffert H, Metz D, Pinzer B, Schiller F (1978) Fotochemotherapie mit 8-methoxypsoralen und UVA bei Psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatol Monatsschr 164(6):401–407 [PubMed]

- 74.Khurshid K, Haroon TS, Hussain I, Pal SS, Jahangir M, Zaman T (2000) Psoralen-ultraviolet A therapy vs. psoralen-ultraviolet B therapy in the treatment of plaque-type psoriasis: our experience with fitzpatrick skin type IV. Int J Dermatol 39(11):865–867 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Arnold WP, van Andel P, de Hoop D, de Jong-Tieben L, Visser-van Andel M (2001) A comparison of the effect of narrow-band ultraviolet B in the treatment of psoriasis after salt-water baths and after 8-methoxypsoralen baths. Br J Dermatol 145(2):352–354 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Park YK, Kim HJ, Koh YJ (1988) Combination of photochemotherapy (PUVA) and ultraviolet B (UVB) in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol 15(1): 68–71 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Kabat-Zinn J, Wheeler E, Light T, Skillings A, Scharf MJ, Cropley TG, Hosmer D, Bernhard JD (1998) Influence of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy (UVB) and photochemotherapy (PUVA). Psychosom Med 60(5):625–632 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Frappaz A, Thivolet J (1993) Calcipotriol in combination with PUVA: a randomized double blind placebo study in severe psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol 3:351–354

- 79.Rogers S, Marks J, Shuster S, Briffa DV, Warin A, Greaves M (1979) Comparison of photochemotherapy and dithranol in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Lancet 1(8114):455–458 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Vella Briffa D, Rogers S, Greaves MW, Marks J, Shuster S, Warin AP (1978) A randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing photochemotherapy with dithranol in the initial treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol 3(4):339–347 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Parker S, Coburn P, Lawrence C, Marks J, Shuster S (1984) A randomized double-blind comparison of PUVA-etretinate and PUVA-placebo in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 110(2):215–220 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Dover JS, McEvoy MT, Rosen CF, Arndt KA, Stern RS (1989) Are topical corticosteroids useful in phototherapy for psoriasis? J Am Acad Dermatol 20(5 Pt 1):748–754 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Hanke CW, Steck WD, Roenigk HH Jr (1979) Combination therapy for psoriasis. Psoralens plus long-wave ultraviolet radiation with betamethasone valerate. Arch Dermatol 115(9):1074–1077 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Koo JY, Lowe NJ, Lew-Kaya DA, Vasilopoulos AI, Lue JC, Sefton J, Gibson JR (2000) Tazarotene plus UVB phototherapy in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 43(5 Pt 1):821–828 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.McBride SR, Walker P, Reynolds NJ (2003) Optimizing the frequency of outpatient short-contact dithranol treatment used in combination with broadband ultraviolet B for psoriasis: a randomized, within-patient controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 149(6):1259–1265 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Levell NJ, Shuster S, Munro CS, Friedmann PS (1995) Remission of ordinary psoriasis following a short clearance course of cyclosporin. Acta Derm Venereol 75(1):65–69 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Petzelbauer P, Honigsmann H, Langer K, Anegg B, Strohal R, Tanew A, Wolff K (1990) Cyclosporin A in combination with photochemotherapy (PUVA) in the treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 123(5):641–647 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Franchi C, Cainelli G, Frigerio E, Garutti C, Altomare GF (2004) Association of cyclosporine and 311 nm UVB in the treatment of moderate to severe forms of psoriasis: a new strategic approach. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 17(3):401–406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Paul BS, Momtaz K, Stern RS, Arndt KA, Parrish JA (1982) Combined methotrexate–ultraviolet B therapy in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 7(6):758–762 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Morison WL, Momtaz K, Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB (1982) Combined methotrexate-PUVA therapy in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 6(1):46–51 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Caca-Biljanovska NG, V’Lckova-Laskoska MT (2002) Management of guttate and generalized psoriasis vulgaris: prospective randomized study. Croat Med J 43(6): 707–712 [PubMed]

- 92.Saurat JH, Geiger JM, Amblard P, Beau J-C, Boulanger A, Claudy A et al (1988) Randomized double-blind multicenter study comparing acitretin-PUVA and placebo-PUVA in the treatment of severe psoriasis. Dermatoligica 177:218–224 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Lauharanta J, Geiger JM (1989) A double-blind comparison of acitretin and etretinate in combination with bath PUVA in the treatment of extensive psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 121(1):107–112 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Orfanos CE, Steigleder GK, Pullmann H, Bloch PH (1979) Oral retinoid and UVB radiation: a new, alternative treatment for psoriasis on an out-patient basis. Acta Derm Venereol 59(3):241–244 [PubMed]

- 95.Calzavara-Pinton P (1998) Narrow band UVB (311 nm) phototherapy and PUVA photochemotherapy: a combination. J Am Acad Dermatol 38(5 Pt 1):687–690 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.Markham T, Rogers S, Collins P (2003) Narrowband UV-B (TL-01) phototherapy vs oral 8-methoxypsoralen psoralen-UV-A for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 139(3):325–328 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Calzavara-Pinton P, Ortel B, Carlino A, Honigsmann H, De Panfilis G (1992) A reappraisal of the use of 5-methoxypsoralen in the therapy of psoriasis. Exp Dermatol 1(1):46–51 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Henseler T, Wolff K, Hönigsmann H, Christophers E (1981) Oral 8-methoxypsoralen photochemotherapy of psoriasis. The European PUVA Study: a cooperative study among 18 European centres. Lancet 11:853–857 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Torras H, Aliaga A, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, Hernandez I, Gardeazabal J, Quintanilla E, Mascaro JM (2004) A combination therapy of calcipotriol cream and PUVA reduces the UVA dose and improves the response of psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Treat 15(2):98–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Hacker SM, Rasmussen JE (1992) The effect of flash lamp-pulsed dye laser on psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 128(6):853–855 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Gordon KB, Papp KA, Hamilton TK, Walicke PA, Dummer W, Li N, Bresnahan BW, Menter A (2003) Efalizumab for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290(23):3073–3080 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.Lebwohl M, Tyring SK, Hamilton TK, Toth D, Glazer S, Tawfik NH, Walicke P, Dummer W, Wang X, Garovoy MR, Pariser D (2003) A novel targeted T-cell modulator, efalizumab, for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 349(21):2004–2013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Leonardi CL, Papp KA, Gordon KB, Menter A, Feldman SR, Caro I, Walicke PA, Compton PG, Gottlieb AB (2005) Extended efalizumab therapy improves chronic plaque psoriasis: results from a randomized phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 52(3 Pt 1):425–433 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Menter A, Gordon K, Carey W, Hamilton T, Glazer S, Caro I, Li N, Gulliver W (2005) Efficacy and safety observed during 24 weeks of efalizumab therapy in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 141(1):31–38 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.Papp K, Bissonnette R, Krüger JG, Carey W, Gratton D, Gulliver WP, Lui H (2001) The treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a new anti-CD11a monoclonal antibody. J Am Acad Dermatol 45(5):665–674 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 106.Gottlieb AB, Gordon KB, Lebwohl MG, Caro I, Walicke PA, Li N, Leonardi CL (2004) Extended efalizumab therapy sustains efficacy without increasing toxicity in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol 3(6):614–624 [PubMed]

- 107.Gottlieb AB, Matheson RT, Lowe N, Krueger GG, Kang S, Goffe BS, Gaspari AA, Ling M, Weinstein GD, Nayak A, Gordon KB, Zitnik R (2003) A randomized trial of etanercept as monotherapy for psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 139(12):1627–1632; discussion 1632 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT, Goffe BS, Zitnik R, Wang A, Gottlieb AB (2003) Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med 349(21):2014–2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Costanzo A, Mazzotta A, Papoutsaki M, Nistico S, Chimenti S (2005) Safety and efficacy study on etanercept in patients with plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 152(1):187–189 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, Birbara C, Beutler A, Guzzo C, Zhou B, Dooley LT, Kavanaugh A (2005) Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 64(8):1150–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Gottlieb AB, Evans R, Li S, Dooley LT, Guzzo CA, Baker D, Bala M, Marano CW, Menter A (2004) Infliximab induction therapy for patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 51(4):534–542 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Chaudhari U, Romano P, Mulcahy LD, Dooley LT, Baker DG, Gottlieb AB (2001) Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet 357(9271):1842–1847 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Schopf RE, Aust H, Knop J (2002) Treatment of psoriasis with the chimeric monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor alpha, infliximab. J Am Acad Dermatol 46(6):886–891 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 114.Koo J (1998) A randomized, double-blind study comparing the efficacy, safety and optimal dose of two formulations of cyclosporin, Neoral and Sandimmun, in patients with severe psoriasis. OLP302 Study Group. Br J Dermatol 139(1):88–95 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 115.Thaci D, Brautigam M, Kaufmann R, Weidinger G, Paul C, Christophers E (2002) Body-weight-independent dosing of cyclosporine micro-emulsion and three times weekly maintenance regimen in severe psoriasis. A randomised study. Dermatology 205(4):383–388 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Mahrle G, Schulze HG, Färber L, Weidinger G, Steigleder GK (1995) Low-dose short-term cyclosporine versus etretinate in psoriasis: improvement of skin, nail and joint involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol 32(1):78–88 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 117.Ellis CN, Fradin MS, Messana JM, Brown MD, Siegel MT, Howland Hartley A (1991) Cyclosporine for plaque-type psoriasis. Results of a multidose, double-blind trial. N Engl J Med 324:277–284 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 118.Elder C, Moore M, Chang CT, Jin J, Charnick S, Nedelman J, Cohen A, Guzzo C, Lowe N, Simpson K (1995) Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of two formulations of cyclosporine in patients with psoriasis. J Clin Pharmacol 35:865–875 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 119.Engst R, Huber J (1989) Ergebnisse einer Cyclosporin-behandlung bei schwerer, chronischer Psoriasis vulgaris. Hautarzt 40:186–189 [PubMed]

- 120.Laburte C, Grossman R, Abi-Rached J, Abeywickrama KM, Dubertret L (1994) Efficacy and safety of oral cyclosporine A (CYA; Sandimmun) for long-term treatment of chronic severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 130:366–375 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 121.Meffert H, Braeutigam M, Faerber L, Weidinger G (1997) Low-dose (1,25mg/kg) cyclosporine A: treatment of psoriasis and investigation of the influence on lipid profile. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl 77:137–141 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 122.Finzi AF, Mozzanica N, Pigatto PD, Cattaneo A, Ippolito F (1993) Cyclosporine versus etretinate: Italian multicentre comparative trial in severe psoriasis. Dermatology 187(Suppl 1):8–18 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 123.Heydendael VM, Spuls PI, Opmeer BC, de Borgie CA, Reitsma JB, Goldschmidt WF, Bossuyt PM, Bos JD, de Rie MA (2003) Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 349(7):658–665 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 124.Reitamo S, Spuls P, Sassolas B, Lahfa M, Claudy A, Griffiths CE (2001) Efficacy of sirolimus (rapamycin) administered concomitantly with a subtherapeutic dose of cyclosporin in the treatment of severe psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 145(3):438–445 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 125.Grossman RM, Thivolet J, Claudy A, Souteyrand P, Guilhou JJ, Thomas P, Amblard P, Belaich S, de Belilovsky C, de la Brassinne M et al (1994) A novel therapeutic approach to psoriasis with combination calcipotriol ointment and very low-dose cyclosporine: results of a multicenter placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 31(1):68–74 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 126.Finzi AF, Mozzanica N, Cattaneo A, Chiappino G, Pigatto PD (1989) Effectiveness of cyclosporine treatment in severe psoriasis: A clinical and immunologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 21:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 127.Higgins E, Munro C, Marks J, Friedmann PS, Shuster S (1989) Relapse rates in moderately severe chronic psoriasis treated with cyclosporine A. Br J Dermatol 121:71–74 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 128.Litjens NH, Nibbering PH, Barrois AJ, Zomerdijk TP, Van Den Oudenrijn AC, Noz KC, Rademaker M, Van De Meide PH, Van Dissel JT, Thio B (2003) Beneficial effects of fumarate therapy in psoriasis vulgaris patients coincide with downregulation of type 1 cytokines. Br J Dermatol 148(3):444–451 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 129.Altmeyer PJ, Matthes U, Pawlak F, Hoffmann K, Frosch PJ, Ruppert P, Wassilew SW, Horn T, Kreysel HW, Lutz G, Barth J, Rietzschel I, Joshi R (1994) Antipsoriatic effect of fumaric acid derivatives. Results of a multicentre double-blind study in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 30(6):977–981 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 130.Gollnick H, Altmeyer P, Kaufmann R, Ring J, Christophers E, Pavel S, Ziegler J (2002) Topical calcipotriol plus oral fumaric acid is more effective and faster acting than oral fumaric acid monotherapy in the treatment of severe chronic plaque psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 205(1):46–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 131.Kolbach DN, Nieboer C (1992) Fumaric acid therapy in psoriasis: results and side effects of 2 years of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 27(5 Pt 1):769–771 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 132.Nugteren-Huying WM, Schroeff JGvd, Hermans J, Suurmond D (1990) Fumaric acid therapy for psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placeFumaric acid therapy for psoriasis: a randomized, double-bo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 22:311–312 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 133.Altmeyer P, Hartwig R, Matthes U (1996) Das Wirkungs-und Sicherheitsprofil von Fumarsäureestern in der oralen Langzeittherapie bei schwerer therapieresistenter Psoriasis vulgaris. Eine Untersuchung an 83 Patienten. Hautarzt 47(3):190–196 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 134.Bayard W, Hunziker T, Krebs A, Speiser P, Joshi R (1987) Peroral long-term treatment of psoriasis using fumaric acid derivative. Hautarzt 38(5):279–285 [PubMed]

- 135.Carboni I, De Felice C, De Simoni I, Soda R, Chimenti S (2004) Fumaric acid esters in the treatment of psoriasis: an Italian experience. J Dermatol Treat 15(1):23–26 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 136.Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P (1998) Treatment of psoriasis with fumaric acid esters: results of a prospective multicentre study. German Multicentre Study. Br J Dermatol 138(3):456–460 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 137.Roenigk HH Jr, Auerbach R, Maibach H, Weinstein G, Lebwohl M (1998) Methotrexate in psoriasis: consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol 38(3):478–485 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 138.Weinstein GD, Frost P (1971) Methotrexate for psoriasis. A new therapeutic schedule. Arch Dermatol 103:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 139.Nyfors A, Brodthagen H (1970) Methotrexate for psoriasis in weekly oral doses without any adjunctive therapy. Dermatologica 140:345–355 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 140.van de Kerkhof PC, Cambazard F, Hutchinson PE, Haneke E, Wong E, Souteyrand P, Damstra RJ, Combemale P, Neumann MH, Chalmers RJ, Olsen L, Revuz J (1998) The effect of addition of calcipotriol ointment (50 micrograms/g) to acitretin therapy in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 138(1):84–89 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 141.Kragballe K, Jansen CT, Geiger JM, Bjerke JR, Falk ES, Gip L, Hjorth N, Lauharanta J, Mork NJ, Reunala T et al (1989) A double-blind comparison of acitretin and etretinate in the treatment of severe psoriasis. Results of a Nordic multicentre study Acta Derm Venereol 69(1):35–40 [PubMed]

- 142.Gupta AK, Goldfarb MT, Ellis CN, Voorhees JJ (1989) Side-effect profile of acitretin therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 20(6):1088–1093 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 143.Carlin CS, Callis KP, Krueger GG (2003) Efficacy of acitretin and commercial tanning bed therapy for psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 139(4):436–442 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 144.Halevy S, Giryes H, Friger M, Sukenik H (1997) Dead sea bath salt for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: a double- blind controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 9(3):237–242 [DOI]

- 145.Robertson DB, McCarty JR, Jarratt M (1978) Treatment of psoriasis with 8-methoxypsoralen and sunlight. South Med J 71(11):1345–1349 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 146.Fleischer ABJ, Clark AR, Rapp SR, Reboussin DM, Feldman SR (1997) Commercial tanning bed treatment is an effective psoriasis treatment:results from an uncontrolled clinical trial. J Invest Dermatol 109(2):170–174 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 147.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, Bowcock S, Main CJ, Griffiths CE (2002) A cognitive-behavioural symptom management programme as an adjunct in psoriasis therapy. Br J Dermatol 146(3):458–465 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 148.Tausk F, Whitmore SE (1999) A pilot study of hypnosis in the treatment of patients with psoriasis. Psychother Psychosom 68(4):221–225 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 149.Nast A, Kopp I, Augustin M), Banditt KB, Boehncke WH, Follmann M, Friedrich M, Huber M, Kahl C, Klaus J, Koza J, Kreiselmaier I, Mohr J, Mrowietz U, Ockenfels HM, Orzechowski HD, Prinz J, Reich K, Rosenbach T, Rosumeck S, Schlaeger M, Schmid-Ott G, Sebastian M, Streit V, Weberschock T, Rzany B (2006) S3-Leitlinie zur Therapie der Psoriasis vulgaris. JDDG Suppl 2:S1–S126