Abstract

Objective: This review focuses on classification and description of and current treatment recommendations for psychocutaneous disorders. Medication side effects of both psychotropic and dermatologic drugs are also considered.

Data Sources: A search of the literature from 1951 to 2004 was performed using the MEDLINE search engine. English-language articles were identified using the following search terms: skin and psyche, psychiatry and dermatology, mind and skin, psychocutaneous, and stress and skin.

Data Synthesis: The psychotropic agents most frequently used in patients with psychocutaneous disorders are those that target anxiety, depression, and psychosis. Psychiatric side effects of dermatologic drugs can be significant but can occur less frequently than the cutaneous side effects of psychiatric medications. In a majority of patients presenting to dermatologists, effective management of skin conditions requires consideration of associated psychosocial factors. For some dermatologic conditions, there are specific demographic and personality features that commonly associate with disease onset or exacerbation.

Conclusions: More than just a cosmetic disfigurement, dermatologic disorders are associated with a variety of psychopathologic problems that can affect the patient, his or her family, and society together. Increased understanding of biopsychosocial approaches and liaison among primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and dermatologists could be very useful and highly beneficial.

Psychodermatology addresses the interaction between mind and skin. Psychiatry is more focused on the “internal” nonvisible disease, and dermatology is focused on the “external” visible disease. Connecting the 2 disciplines is a complex interplay between neuroendocrine and immune systems that has been described as the NICS, or the neuro-immuno-cutaneous system. The interaction between nervous system, skin, and immunity has been explained by release of mediators from NICS.1 In the course of several inflammatory skin diseases and psychiatric conditions, the NICS is destabilized. In more than one third of dermatology patients, effective management of the skin condition involves consideration of associated psychologic factors.2 Dermatologists have stressed the need for psychiatric consultation in general, and psychological factors may be of particular concern in chronic intractable dermatologic conditions, such as eczema, prurigo, and psoriasis.3–5

Lack of positive nurturing during childhood may lead in adulthood to disorders of self-image, distortion of body image, and behavioral problems.6 The emotional problems due to skin disease include shame, poor self-image, and low self-esteem. The psychosocial impact depends upon a number of factors, including the natural history of the disease in question; the patient's demographic characteristics, personality traits, and life situation; and the meaning of the disease in the patient's family and culture.7 Hostile personality characteristics, dysthymic states, and neurotic symptoms have been frequently observed in common skin conditions like psoriasis, urticaria, and alopecia.8 It has been reported that female dermatology patients and widows/widowers exhibit a higher prevalence of associated psychiatric comorbidity.9

It has been reported that psychologic stress perturbs epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis, and it may act as precipitant for some inflammatory disorders like atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.10 Patients with psychocutaneous disorders frequently resist psychiatric referral, and the liaison among primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and dermatologists can prove very useful in the management of these conditions.

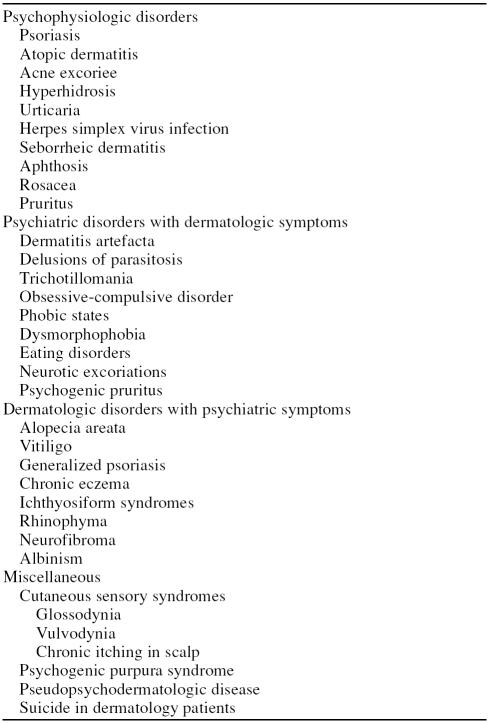

Although there is no single universally accepted classification system of psychocutaneous disorders and many of the conditions are overlapped into different categories, the most widely accepted system is that devised by Koo and Lee11: (1) psychophysiologic disorders, (2) psychiatric disorders with dermatologic symptoms, and (3) dermatologic disorders with psychiatric symptoms (Table 1). Several other conditions of interest can be grouped under a heading of miscellaneous, and medication side effects of both psychotropic and dermatologic drugs should also be considered.

Table 1.

Classification of Psychodermatologic Disorders

A search of the literature from 1951 to 2004 was performed using the MEDLINE search engine. English-language articles were identified using the following search terms: skin and psyche, psychiatry and dermatology, mind and skin, psychocutaneous, and stress and skin.

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGIC DISORDERS

Here psychiatric factors are instrumental in the etiology and course of skin conditions. The skin disease is not caused by stress but appears to be precipitated or exacerbated by stress.11 The proportion of patients reporting emotional triggers varies with the disease, ranging from approximately 50% (acne) to greater than 90% (rosacea, alopecia areata, neurotic excoriations, and lichen simplex) and may be 100% for patients with hyperhidrosis.12 Stress management, relaxation techniques, benzodiazepines, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been found useful in these disorders.

Psoriasis

Onset or exacerbation of psoriasis can be predated by a number of common stressors. Stress has been reported in 44% of patients prior to the initial flare of psoriasis, and recurrent flares have been attributed to stress in up to 80% of individuals.13,14 Early onset psoriasis before age 40 years may be more easily triggered by stress than late onset disease, and patients who self-report high levels of psychologic stress may have more severe skin and joint symptoms.15–17

The most common psychiatric symptoms attributed to psoriasis include disturbances in body image and impairment in social and occupational functioning.18 Quality of life may be severely affected by the chronicity and visibility of psoriasis as well as by the need for lifelong treatment. Five dimensions of the stigma associated with psoriasis have been identified: (1) anticipation of rejection, (2) feelings of being flawed, (3) sensitivity to the attitudes of society, (4) guilt and shame, and (5) secretiveness.19 Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation occur more frequently in severe psoriasis compared with controls.20 Depression may modulate itch perception, exacerbate pruritus, and lead to difficulties with initiating and maintaining sleep. In a study21 of 217 psoriasis patients with associated depression, 9.7% acknowledged a “wish to be dead,” and 5.5% reported active suicidal ideation.

Psoriasis also affects sexual functioning. In one study,22 30% to 70% of patients reported a decline in sexual activity, and these patients more frequently reported joint pains, psoriasis affecting the groin region, scaling, and pruritus compared with patients without sexual complaints. These patients also had higher depression scores, greater tendency to seek the approval of others, and a marginally greater tendency to drink alcohol.22

Psychophysiologically, neuropeptides such as vasoactive intestinal peptide and substance P may have a role in the development of psoriatic lesions.23 Imbalance of vasoactive intestinal peptide and substance P has been reported in psoriasis, and there may be an associated increase in stress-induced autonomic response and diminished pituitary-adrenal activity.24,25 Biofeedback, meditation, hypnosis-induced relaxation, behavioral techniques, symptom-control imagery training, and antidepressants are important adjuncts to standard therapies for this disease.18,26–28

Atopic Dermatitis

Stressful life events preceding the onset of disease have been found in more than 70% of atopic dermatitis patients.29 Symptom severity has been attributed to interpersonal and family stress, and problems in psychosocial adjustment and low self-esteem have been frequently noted.30,31 Dysfunctional family dynamics may lead to lack of therapeutic response as well as to developmental arrest.32,33 Williams34 found that 45% of children with atopic dermatitis whose mothers received counseling were clear of lesions versus only 10% in the group receiving conventional (nonpsychosocial) therapy alone. Chronic infantile eczema has been shown to respond when parental education was added to conventional treatment.33,35 Psychologic interventions, such as brief dynamic psychotherapy, biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, and hypnosis, can be important adjuncts to treatment.36–40 Benzodiazepines and antidepressants are frequently used for treatment.41

Acne Excoriee

The habitual act of picking at skin lesions, apparently driven by compulsion and psychologic factors independent of acne severity, has been reported in the perpetuation of self-excoriation.42 Most patients with this disease are females with late onset acne. Psychiatric comorbidity of acne excoriee includes body image disorder, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), delusional disorders, personality disorders, and social phobias.43–47 Immature coping mechanisms and low self-esteem have also been associated. Interesting gender differences have been observed in this disease. In men, self-excoriation is exacerbated by a coexisting depression or anxiety, while in women this behavior may be a manifestation of immature personality and serve as an appeal for help.48 SSRIs, doxepin, clomipramine, naltrexone, pimozide, and habit-reversal behavior therapy have been used in the treatment of this condition, and recent reports suggest that olan-zapine (2.5–5 mg daily for 2–4 weeks) may also be helpful.49–51

Hyperhidrosis

With this disease, persistent sweating is brought on by emotional stimuli. These patients have social phobic and avoidance symptoms, sometimes leading to devastating consequences at work and social activities. States of tension, fear, and rage are common. The psychopathologic characteristics of patients with essential hyperhidrosis have been categorized into 3 groups: (1) objectifiable hyperhidrosis due to a psychosomatic disorder like atopic dermatitis; (2) objectifiable hyperhidrosis with secondary psychiatric sequelae like social phobia, anxiety, and depression as a consequence of chronic skin disease; and (3) delusional hyperhidrosis without any objective evidence of hyperhidrosis.52 This last category has been increasingly observed in patients with body dysmorphic disorder.53 Patients with hyperhidrosis have poorer coping ability and more emotional problems compared to patients with other dermatology problems.54 The SSRIs and benzodiazepines have been used with variable success in the treatment of hyperhidrosis associated with social anxiety disorder.55

Urticaria

Severe emotional stress may exacerbate preexisting urticaria.56 Increased emotional tension, fatigue, and stressful life situations may be primary factors in more than 20% of cases and are contributory in 68% of patients. Difficulties with expression of anger and a need for approval from others are also common.57,58 Patients with this disorder may have symptoms of depression and anxiety, and the severity of pruritus appears to increase as the severity of depression increases.59,60 Cold urticaria may be associated with hypomania during winter and recurrent idiopathic urticaria with panic disorder.61,62 Doxepin, nor-triptyline, and SSRIs have been reported to be useful in the management of chronic idiopathic urticaria.63,64 Recurrent urticaria associated with severe anxiety disorders has been treated successfully with fluoxetine and sertra-line.62 Individual and group psychotherapies, stress management, and hypnosis with relaxation may also be useful in these patients.65,66

Herpes Simplex Virus, Herpes Zoster, and Human Papillomavirus Infections

There is increasing evidence that stress has a role in recurrent herpetic infection. In one study, 67 experimentally induced emotional stress led to herpes simplex virus reactivation. Other studies have demonstrated an inverse correlation between stress level and present CD4 helper/ inducer T lymphocytes, thus contributing to herpes virus activation and recurrences.68,69 It has also been suggested that stress-induced release of immunomodulating signal molecules (e.g., catecholamines, cytokines, and glucocorticoids) compromises the host's cellular immune response leading to reactivation of herpes simplex virus.70 Relaxation treatment and frontalis electromyographic biofeedback may reduce the frequency of recurrences.71

Herpes zoster has been associated with chronic child abuse, and severe psychologic stress of any sort may depress cell-mediated immune response, predisposing children to the virus.72 Effects of hypnotherapy on common warts have been well documented in the literature.73,74 Feelings of depression, anger, and shame and the negative effects on sexual enjoyment and activity associated with human papillomavirus infections have also been reported.75

Other disorders in which psychologic factors are important in the genesis and course of disease include seborrheic dermatitis, aphthosis, rosacea, pruritus, and dyshidrosis.

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS WITH DERMATOLOGIC SYMPTOMS

These disorders have received little emphasis in the psychiatry or dermatology literature, even though they may be associated with suicide and unnecessary surgical procedures. Most of these disorders occur in the context of somatoform disorder, anxiety disorder, factitious disorder, impulse-control disorder, or eating disorder.

Dermatitis Artefacta

A form of factitious disorder, dermatitis artefacta involves self-inflicted cutaneous lesions that the patient typically denies having induced. The condition is more common in women than in men (3:1 to 20:1).76 The lesions are usually bilaterally symmetrical, within easy reach of the dominant hand, and may have bizarre shapes with sharp geometrical or angular borders, or they may be in the form of burn scars, purpura, blisters, and ulcers. Erythema and edema may be present. Patients may induce lesions by rubbing, scratching, picking, cutting, punching, sucking, or biting or by applying dyes, heat, or caustics. Some patients inject substances, including feces and blood. Reported associated conditions include OCD, borderline personality disorder, depression, psychosis, and mental retardation.77,78 In one survey, dermatitis artefacta was found in 4% of 457 institutionalized children and adolescents with mental retardation.79 Physical and sexual abuse must be considered in the differential diagnosis as well as psychosocial stressors.80,81 Malignant transformations of dermatitis artefacta lesions sometimes resulting in death have been reported.82 Hypnosis can be useful in the evaluation of suspected cases. Direct confrontation of the patient should be avoided, and a supportive, nonjudgmental approach is the mainstay of management. Patients should be seen on an ongoing basis for supervision and support, whether or not lesions remain present.83 Relaxation exercises, antianxiety drugs, antidepressants such as SSRIs, and low-dose atypical antipsychotics might also be useful.84,85 In some case reports, an excellent clinical response has been observed with low-dose olanzapine.86

Delusions of Parasitosis

DSM-IV-TR defines delusions of parasitosis as delusional disorder of somatic type. Patients believe that organisms infest their bodies; they often present with small bits of excoriated skin, debris, insects, or insect parts that they show as evidence of the infection. Pimozide, 1 to 10 mg/day, has been the treatment of choice in past87–89; risperidone, trifluoperazine, haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and electroconvulsive therapy are among other treatments reported to be useful.90–92

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is the recurrent pulling out of one's hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss. In the DSM-IV-TR, trichotillomania is classified as a disorder of impulse control; however, many dermatologists regard this behavior as quite compulsive. Childhood trauma and emotional neglect may play a role in the development of this disorder.93 Associated psychiatric conditions may include anxiety, depression, dementia, mental retardation, mood or adjustment disorder, comorbid substance abuse, and eating disorder.78,94,95 The patients experience an increasing sense of tension immediately before an episode of hair pulling and when attempting to resist the behavior; they feel relief of tension and sometimes a feeling of gratification after hair pulling.96 This dynamic highlights similarities and differences between trichotillomania and OCD and tic disorder. Specifically, the behavior may not be regarded as ego-dystonic, but it does share many emotional factors with compulsions. Interestingly, many treatments for tricho-tillomania are similar to those utilized in OCD. Thus, along with symptomatic treatment, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, clomipramine, lithium, buspirone, risperidone, cognitive-behavioral therapy, habit-reversal therapy, and hypnotherapy have been reported to be beneficial.97,98

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

Patients usually present to dermatologists because of skin lesions resulting from scratching, picking, and other self-injurious behaviors. They typically have an increased level of psychiatric symptomatology compared with age and sex matched controls taken from the general population of dermatology patients, and many patients experience negative stigmatization in their daily life.99–101 Common behaviors include compulsive pulling of scalp, eyebrow, or eyelash hair; biting of the nails and lips, tongue, and cheeks; and excessive hand washing. In one report,102 the most common site involved was the face, followed by back and neck. Koo and Smith103 have found that OCD in child and adolescent dermatology patients most commonly presents as trichotillomania, onychotillomania, and acne excoriee. SSRIs, clomipramine, behavior modification, and psychodynamic psychotherapy have been reported to be effective.87

Phobic States

Among the commonly feared conditions for people with phobic states are sexually transmitted diseases, cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and herpes. Phobias about dirt and bacteria may lead to repeated hand washing, resulting in irritant dermatitis. In some cases, patients mutilate themselves in an attempt to remove pigmented nevi that they believe are related to possible cancer.104 Cognitive-behavioral therapy plays a major role in treatment.

Dysmorphophobia

This condition is also called body dysmorphic disorder or dermatological non-disease.105 Patients with this condition are rich in symptoms but poor in signs of organic disease. Self-reported “complaints” or “concerns” usually occur in 3 main areas: face, scalp, and genitals. Facial symptoms include excessive redness, blushing, scarring, large pores, facial hair, and protruding or sunken parts of face. Other symptoms are hair loss, red scrotum, urethral discharge, and herpes and AIDS phobia. Strategies to relieve the anxiety due to the perceived defects may include camouflaging the lesions, mirror checking, comparison of “defects” with the same body parts on others, questioning/reassurance seeking, mirror avoidance, and grooming to cover up “defects.”106 Women are more likely than men to be preoccupied with the appearance of their hips or their weight, to pick their skin, to camouflage defects with makeup, and to have comorbid bulimia nervosa. Men are more likely than women to be preoccupied with body build, genitals, and hair thinning and to be unmarried and to abuse alcohol.107 Patients with body image disorders, especially those involving the face, may be suicidal.108 Associated comorbidity in dysmorphophobia may include depression, impairment in social and occupational functioning, social phobias, OCD, skin picking, marital difficulties, and substance abuse.109,110 SSRIs, clomipramine, haloperidol, and cognitive-behavioral therapy have been used in this condition with variable success.111,112

Eating Disorders

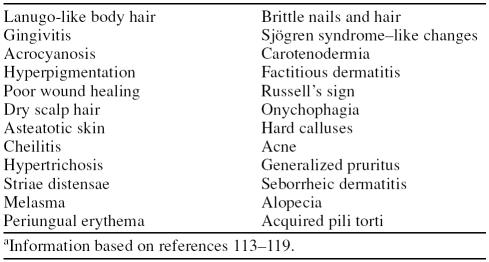

Dermatologic signs and symptoms in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are primarily the result of starvation and malnutrition or self-induced vomiting and the use of laxatives, emetics, or diuretics. The skin changes are more frequently seen when body mass index reaches 16 kg/m2 or less. The skin signs associated with eating disorders are summarized in Table 2.113–119 Other than weight-related body image issues, patients' most common concerns relate to skin, teeth, jaws, nose, and eyes. The high prevalence of skin involvement has been linked to core “ego deficits” and may be an index of severity disturbance in overall body image; acne may also be a risk factor for anorexia nervosa.118,119 Antidepressants, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psycho-educational approaches, and family therapy have been employed in the treatment of eating disorders.120–122

Table 2.

Dermatologic Signs of Eating Disordersa

Neurotic Excoriations

As per DSM-IV-TR classification an impulse-control disorder not otherwise specified, neurotic excoriations are self-inflicted lesions that typically present as weeping, crusted, or lichenified lesions with postinflammatory hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation. The preferred term for this disorder is pathologic skin picking.123 Usual sites are the extensor aspects of extremities, scrotum, and perianal regions. Repetitive scratching, initiated by an itch or an urge to excoriate a benign skin lesion, produces lesions. The behaviors of these patients sometimes resemble those with OCD.

Psychopathologically, patients with neurotic excoriations have personalities with compulsive and perfectionist traits. Common concurrent psychiatric diagnoses are OCD and other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, body dysmorphic disorders, substance abuse disorders, eating disorders, trichotillomania, compulsive-buying disorder, and personality disorders (obsessive-compulsive and borderline personality disorder).124–127 The extent and degree of self-excoriation has been reported to be a reflection of the underlying personality. Family- and work-related stress has also been implicated.

Phenomenologically, there is an overlap between trichotillomania and pathologic skin picking; both conditions are similar in demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and personality traits.128 In rare cases, there are medical complications, such as epidural abscess with subsequent paralysis, as a result of compulsive picking.129 SSRIs, doxepin, clomipramine, naltrexone, pimozide, olanzapine, benzodiazepines, amitriptyline, habit-reversal behavioral therapy, and supportive psychotherapy have been used in the treatment.123,129–131

Psychogenic Pruritus

In this disorder, there are cycles of stress leading to pruritus as well as of the pruritus contributing to stress. Psychologic stress and comorbid psychiatric conditions may lower the itch threshold or aggravate itch sensitivity.132 Stress liberates histamine, vasoactive neuropeptides, and mediators of inflammation, while stress-related hemodynamic changes (e.g., variation in skin temperature, blood flow, and sweat response) may all contribute to the itch-scratch-itch cycle.133 Psychogenic pruritus has been noted in patients with depression, anxiety, aggression, obsessional behavior, and alcoholism. The degree of depression may correlate with pruritus severity.134 Habit-reversal training, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and anti-depressants may be beneficial.130

DERMATOLOGIC DISORDERS WITH PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS

This category includes patients who have emotional problems as a result of having skin disease. The skin disease in these patients may be more severe than the psychiatric symptoms, and, even if not life threatening, it may be considered “life ruining.”87 Symptoms of depression and anxiety, work-related problems, and impaired social interactions are frequently observed.135 Psoriasis, chronic eczema, various ichthyosiform syndromes, rhinophymas, neurofibromas, severe acne, and other cosmetically disfiguring cutaneous lesions have grave effects on psychosocial interactions, self-esteem, and body image; major depression and social phobia may develop.

Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata is a nonscarring type of hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body. The influence of psychologic factors in the development, evolution, and therapeutic management of alopecia areata is well documented. Acute emotional stress may precipitate alopecia areata, perhaps by activation of overexpressed type 2 β corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors around the hair follicles, and lead to intense local inflammation.136 Release of substance P from peripheral nerves in response to stress has also been reported, and prominent substance P expression is observed in nerves surrounding hair follicles in alopecia are-ata patients.137 Substance P-degrading enzyme neutral en-dopeptidase has also been strongly expressed in affected hair follicles in the acute-progressive as well as the chronic-stable phase of the disorder. Comorbid psychiatric disorders are also common and include major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, phobic states, and paranoid disorder.138,139 A very strong family history and concurrent atopic and associated autoimmune diseases are common in alopecia areata patients.140 In a study141 with 31 patients, 23 patients (74%) had lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. Major depression and generalized anxiety disorder may occur in as many as 39% of patients, and those with patchy alopecia areata may be more likely to have generalized anxiety disorder. Increased rates of psychiatric diseases in first-degree relatives of patients with alopecia areata have also been noticed, including anxiety disorder (58%), affective disorder (35%), and substance abuse (35%).141

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a specific type of leukoderma characterized by depigmentation of the epidermis. It is associated with more psychosocial embarrassment than any other skin condition. In some studies, patients with vitiligo have been found to have significantly more stressful life events compared with controls, suggesting that psychologic distress may contribute to onset.142 Links between catecholamine-based stress, genetic susceptibility, and a characteristic personality structure have been postulated.143 Psychiatric morbidity is typically reported in approximately one third of patients,142 but, in one study, 56% of the sample had adjustment disorder and 29% had depressive disorders.144 Patients with vitiligo are frightened and embarrassed about their appearance, and they experience discrimination and often believe that they do not receive adequate support from providers.145 Younger patients and individuals in lower socioeconomic groups show poor adjustment, low self-esteem, and problems with social adaptation.146,147 Most patients with vitiligo report a negative impact on sexual relationships and cite embarrassment as the cause.148

MISCELLANEOUS

This group includes disorders or symptoms that are not otherwise classified.

Cutaneous Sensory Syndromes

Patients with these syndromes experience abnormal skin sensations (e.g., itching, burning, stinging, and biting or crawling) that cannot be attributed to any known medical condition. Examples include glossodynia, vulvodynia, and chronic itching in the scalp. These patients often have concomitant anxiety disorder or depression.149

Psychogenic Purpura Syndrome

This condition, also known as autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (Gardner-Diamond syndrome), is seen primarily in emotionally unstable adult females. These patients present with bizarre, painful, recurrent bruises on extremities, frequently after trauma, surgery, or severe emotional stress. The exact mechanism is unclear; however, hypersensitivity to extravasated red cells, autoimmune mechanisms, and increased cutaneous fibrinolytic activity has been implicated in the pathogenesis. These patients may have overt depression, sexual problems, feelings of hostility, obsessive-compulsive behavior,150 borderline personality disorder, and factitious dermatitis.151 Without a correct diagnosis, these individuals can receive treatments that are neither necessary nor effective. The diagnosis can be made in a patient who has atypical history and clinical picture of the syndrome and in whom a skin test with use of the patient's blood reveals a positive reaction.

Pseudopsychodermatologic Disease

These patients may have bizarre skin symptoms without obvious physical findings or a subclinical skin disease that has been eradicated or modified by scratching. Psychodermatologic disease can mimic other skin disorders, and medical disorders can mimic psychodermatologic conditions. Localized bullous pemphigoid lesions, for example, have been mistaken for dermatitis artefacta; multiple sclerosis, folliculitis, hypothyroidism, and vitamin B12 deficiency have been initially diagnosed as delusions of parasitosis.152

Suicide in Dermatology Patients

Suicide has been reported in patients with longstanding debilitating skin diseases and must be considered when evaluating these patients. Even clinically mild to moderate severity skin disease may be associated with significant depression and suicidal ideation.153 Cotterill and Cunliffe154 reported suicides in 16 patients (7 men and 9 women) with body image disorder or severe acne.

THERAPEUTICS

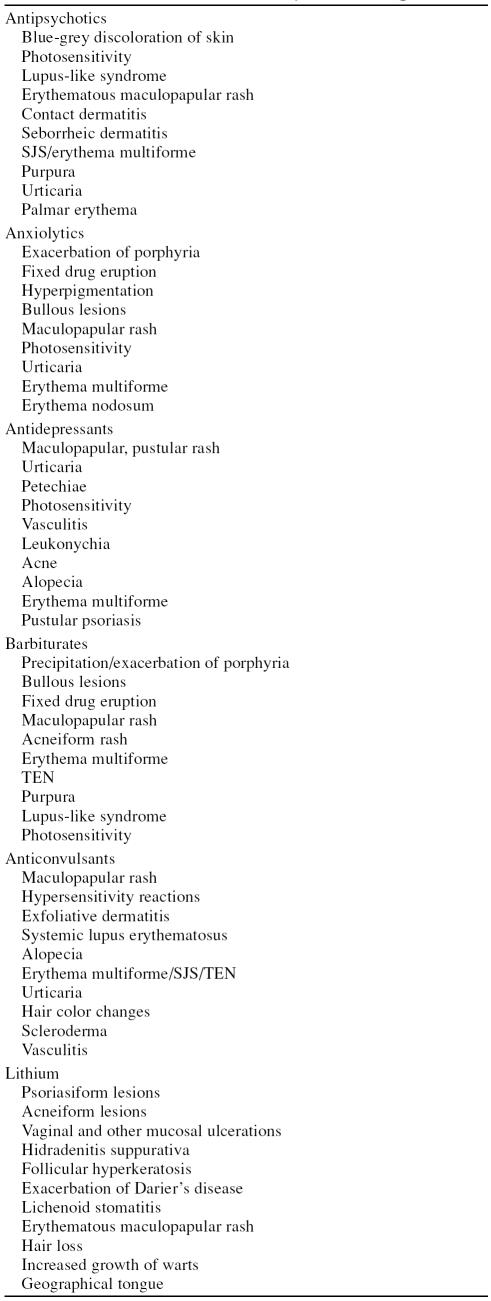

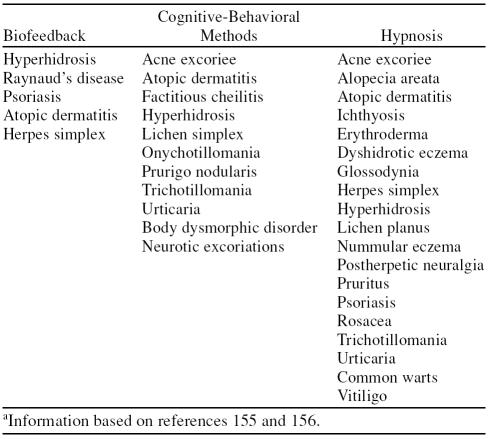

Realistic goals in the treatment of psychodermatologic diseases include reducing pruritus and scratching, improving sleep, and managing psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, anger, social embarrassment, and social withdrawal. Nonpharmacologic management may include psychotherapy, hypnosis, relaxation training, biofeedback, operant conditioning, cognitive-behavioral therapy, meditation, affirmation, stress management, and guided imagery.* The cutaneous side effects of common psychiatric drugs are shown in Table 3. The common skin disorders in which cognitive behavioral methods, hypnosis, and biofeedback have proven useful are listed in Table 4.155,156

Table 3.

Cutaneous Side Effects of Psychiatric Drugs

Table 4.

Nonpharmacologic Treatments of Some Common Skin Disordersa

The choice of psychopharmacologic agent depends upon the nature of the underlying psychopathology (e.g., anxiety, depression, psychosis, compulsion). The efficacy of the tricyclic antidepressants probably is related to antihistaminic, anticholinergic, and centrally mediated analgesic effects. They have been successfully used in chronic urticaria, nocturnal pruritus in atopics, postherpetic neuralgia, psoriasis, acne, hyperhidrosis, alopecia areata, neurotic excoriations, and psychogenic pruritus.157

SSRIs may be beneficial in body dysmorphic disorders, dermatitis artefacta, OCDs, neurotic excoriations, acne excoriee, onychophagia, and psoriasis.158 Cutaneous reactions to these drugs are rare, but toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and papular purpuric erythema on sun-exposed areas have been reported with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine.159–162

The atypical antipsychotics have been used as an augmentation strategy in the treatment of several psychocutaneous disorders. The development of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and weight gain due to certain atypical antipsychotics should be closely monitored and managed accordingly. Recently mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and serotonergic drug, has been reported as useful in chronic itch and several itchy dermatoses.163 Other psychiatric drugs used in dermatology include gabapentin (postherpetic neuralgia and idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia), pimozide (delusions of parasitosis), topiramate and lamotrigine (skin picking), and naltrexone (pruritus).157,164

A variety of cutaneous side effects have been attributed to lithium.165 It has been associated with both the onset and exacerbation of psoriasis, triggering localized or generalized forms of pustular psoriasis.166 Suggested mechanisms for these effects include lithium's role in regulating the second-messenger system (cyclic adenosine monophosphate [cAMP] and phosphoinositides), and its inhibition of adenyl cyclase (leading to decreased levels of cAMP) and inositol monophosphatase (increasing total circulating neutrophil mass).167 An in vitro study demonstrated that lithium influences the cellular communication of psoriatic keratinocyte with HUT 78 lymphocyte by triggering the secretion of TGF α, Il-2, and IFN γ.168 Other cutaneous manifestations attributed to lithium include acneiform lesions,169 vaginal ulcerations,170 mucosal ulcerations,171 hidradenitis suppurativa,172 follicular hyperkeratosis,173 exacerbation of Darier's disease,174 lichenoid stomatitis,175 erythematous maculopapular rash,176 diffuse and localized hair loss, increased growth of warts, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis with ichthyosiform features,177 geographical tongue,178 and follicular mycosis fungoides.179 Interestingly, topical lithium has been used in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis at various centers in Europe.180

Corticosteroids are among the dermatologic agents most often associated with psychiatric symptoms, which include cognitive impairment, mood disorders, depression, delirium, and psychosis.181 Isotretinoin has been implicated in depression, suicidal ideation, and mood swings.182 There are conflicting reports about the relationship between isotretinoin and depression and suicide, but, since its approval in 1982, it has ranked among the top 10 in number of reports to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about suicide.183,184 Many investigators have found no causal connection, however, and most of the published case reports do not meet the established criteria for establishing causality.185,186 Other drugs associated with depression include dapsone, acyclovir, metronidazole, and sulfonamides.187,188

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Psychodermatology has evolved as a new and emerging subspecialty of both psychiatry and dermatology. The connection between skin disease and psyche has, unfortunately, been underestimated. More than just a cosmetic disfigurement, dermatologic disorders are associated with a variety of psychopathologic problems that can affect the patient, his or her family, and society together. Increased understanding of these issues, biopsychosocial approaches, and liaison among primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and dermatologists could be very useful and highly beneficial. The value of shared care of these complex patients with a psychiatrist is highly recommended. Creation of separate psychodermatology units and multicenter research about the relationship of skin and psyche in the form of prospective case-controlled studies and multi-site therapeutic trials can provide more insight into this interesting and exciting field of medicine.

Drug names: acyclovir (Zovirax and others), buspirone (BuSpar and others), chlorpromazine (Thorazine, Sonazine, and others), clomipra-mine (Anafranil and others), doxepin (Sinequan, Zonalon, and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), gabapentin (Neurontin and others), haloperidol (Haldol and others), isotretinoin (Claravis and Amnesteem), lamotrigine (Lamictal and others), lithium (Eskalith, Lithobid, and others), metronidazole (Flagyl, Metrocream, and others), mirtazapine (Remeron and others), naltrexone (Vivitrol, ReVia, and others), nortriptyline (Pamelor and others), olanzapine (Zyprexa), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), pimozide (Orap), risperidone (Risperdal), sertraline (Zoloft and others), topiramate (Topamax), trifluoperazine (Stelazine and others).

Footnotes

The author greatly acknowledges Bryan H. King, M.D., Head, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Vice Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Wash., for his valuable suggestions and for reviewing and editing the final manuscript. Dr. King is an unpaid consultant for Forest, Abbott, Neuropharm, and Seaside Therapeutics.

Dr. Jafferany reports no financial or other relationship related to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- Misery L.. Neuro-immuno-cutaneous system (NICS) Pathol Biol (Paris) 1996;44:867–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin JA, Cotterill JA. Psychocutaneous disorders. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Ebling FJG, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1992 2479–2496. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys F, Humphreys MS.. Psychiatric morbidity and skin disease: what dermatologists think they see. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:679–681. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attah Johnson FY, Mostaghimi H.. Comorbidity between dermatologic diseases and psychiatric disorders in Papua New Guinea. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:244–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capoore HS, Rowland Payne CM, Goldin D.. Does psychological intervention help chronic skin conditions? Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:662–664. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.74.877.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands GE.. Three monosymptomatic hypochondriacal syndromes in dermatology. Dermatol Nurs. 1996;8:421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg IH.. The psychosocial impact of skin disease: an overview. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:473–484. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laihinen A.. Psychosomatic aspects in dermatoses. Ann Clin Res. 1987;19:147–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardi AI, Aberi D, and Melchi CF. et al. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological outpatients: an issue to be recognized. Br J Dermatol. 2000 143:983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit Garg M, Chren M, and Sands L. et al. Psychological stress perturbs epidermal barrier homeostasis. Arch Dermatol. 2001 137:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JYM, Lee CS. General approach to evaluating psychodermatological disorders. In: Koo JYM, Lee CS, eds. Psychocutaneous Medicine. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc. 2003 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cotterill JA.. Psychophysiological aspects of eczema. Semin Dermatol. 1990;9:216–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al'Abadie MS, Kent CG, Gawkrodger DJ.. The relationship between stress and the onset and exacerbation of psoriasis and other skin conditions. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:199–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths CE, Richards HL.. Psychological influence in psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:338–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Watteel GN.. Early onset (< 40 years age) psoriasis is comorbid with greater psychopathology than late onset psoriasis: a study of 137 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:464–466. doi: 10.2340/0001555576464466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvima RJ, Viinamaki H, and Harvima IT. et al. Association of psychic stress with clinical severity and symptoms of psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996 76:467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BS, Youn JI.. Factors influencing psoriasis: an analysis based upon the extent of involvement and clinical type. J Dermatol. 1998;25:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Habermann HF.. Psoriasis and psychiatry: an update. Gen. Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(87)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg IH, Link BG.. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, and Ellis CN. et al. Some psychosomatic aspects of psoriasis. Adv Dermatol. 1990 5:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Schork NJ, and Gupta AK. et al. Suicidal ideation in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1993 32:188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK.. Psoriasis and sex: a study of moderately to severely affected patients. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:259–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber EM, Lanigan SW, Rein G.. The role of psychoneuroimmunology in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Cutis. 1990;46:314–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincelli C, Fantini F, and Magnoni C. et al. Psoriasis and the nervous system. Acta Derm Venereol. 1994 186Suppl. 60–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimidt-Ott G, Jacobs R, and Jager B. et al. Stress-induced endocrine and immunological changes in psoriasis patients and healthy controls: a preliminary study. Psychother Psychosom. 1998 67:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenghi MM, Molinari E, and Gala C. et al. Experience with psoriasis in a psychosomatic dermatology clinic. Acta Derm Venereol. 1994 186:65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L, Crombez JC, and Lassonde M. et al. Psychological stress and psoriasis: experimental and prospective correlational studies. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1991 156:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tausk F, Whitmore SE.. A pilot study of hypnosis in the treatment of patients with psoriasis. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68:221–225. doi: 10.1159/000012336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulstich ME, Williamson DA.. An overview of atopic dermatitis: towards bio-behavioral integration. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:415–417. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil KM, Keefe FJ, and Sampson HA. et al. The relation of stress and family environment to atopic dermatitis symptoms in children. J Psychosom Res. 1987 31:673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus CS, Kerr PE.. Social impact of atopic dermatitis. Med Health R I. 2001;84:294–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett S.. Emotional dysfunction, child family relationship and childhood atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:381–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS, Koblenzer PJ.. Chronic intractable atopic eczema. Its occurrence as a physical sign of impaired parent-child relationships and psychologic developmental arrest: improvement through parent insight and education. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1673–1677. doi: 10.1001/archderm.124.11.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DH.. Management of atopic dermatitis in children; control of maternal rejection factor. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;63:545–560. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1951.01570050003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer PJ.. Parental issues in chronic infantile eczema. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:423–427. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnet J, Jemmer GB.. Anxiety level and severity of skin condition predicts outcome of psychotherapy in atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:632–636. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn DJ, White AE, Varigos GA.. A preliminary study of psychological therapy in the management of atopic eczema. Br J Med Psychol. 1989;62:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1989.tb02832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole WC, Roth HL, Sachs LB.. Group psychotherapy as an aid in the medical treatment of eczema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:286–291. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DG, Beettley FR.. Psychiatric treatment of eczema: a controlled trial. Br Med J. 1971;2:729–734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5764.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Stangier U, Gicler U.. Treatment of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of psychological and dermatological approaches to relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:624–635. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Haberman HF.. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology. A review and guidelines for use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:633–645. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Schork NJ.. Psychological factors affecting self-excoriative behavior in women with mild-to-moderate facial acne vulgaris. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:127–130. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spraker MK.. Cutaneous artefactual disease: an appeal for help. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1983;30:659–668. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, McElory SL, and Mutasim DF. et al. Characteristics of 34 adults with psychogenic excoriation. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998 59:509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon J, Sneddon I.. Acne excoriee: a protective device. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1983.tb01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JYM, Smith LL.. Psychologic aspects of acne. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:185–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M, Bach D.. Psychiatric and psychometric issues in acne excoriee. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;60:207–210. doi: 10.1159/000288694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Schork NJ.. Psychosomatic study of self-excoriative behavior among male acne patients: preliminary observations. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:846–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenta A, Drummond LM.. Acne excoriee: a case report of treatment using habit reversal. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:163–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL.. Psychogenic excoriations: clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:351–359. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK.. Olanzapine may be an effective adjunctive therapy in the management of acne excoriee: a case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:25–27. doi: 10.1177/120347540100500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreydon OP, Heckmann M, Peschen M.. Delusional hyperhidrosis as a risk for medical overtreatment: a case of botuliniphilia. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:538–539. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth W, Linse R.. Botulinophilia: the new life style venoniphilia. Hautarzt. 2001;52:312–315. doi: 10.1007/s001050051313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerer B, Jacobowitz J, Wahba A.. Personality features in essential hyperhidrosis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1980–1981;10:59–67. doi: 10.2190/866g-qqa9-q9ae-15nb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Foa EB, and Connor KM. et al. Hyperhidrosis in social anxiety disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002 26:1327–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees L.. An etiological study of chronic urticaria and angioneurotic edema. J Psychosom Res. 1957;2:172–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(57)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhlin L.. Recurrent urticaria: Clinical investigations of 330 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:369–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb15306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkower ED.. Studies of the personality of patients suffering from urticaria. Psychosom Med. 1953;15:116–126. doi: 10.1097/00006842-195303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, and Schork NJ. et al. Depression modulates pruritus perception: a study of pruritus in psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and chronic idiopathic urticaria. Psychosom Med. 1994 56:36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiro M, Okumura M.. Anxiety, depression, psychosomatic symptoms and autonomic nervous function in patients with chronic urticaria. J Dermatol Sci. 1994;8:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey NS, Mikhail WI.. Seasonal hypomania in a patient with cold urticaria. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:238–241. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK.. Severe recurrent urticaria associated with panic disorder: a syndrome responsive to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants? Cutis 1995;56:53–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Ellis CN.. Antidepressant drugs in dermatology. An update. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:647–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harto A, Sendagorta E, Ledo A.. Doxepin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Dermatoligica. 1985;170:90–93. doi: 10.1159/000249507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shertzer CL, Lookingbill DP.. Effects of relaxation therapy and hypnotizability in chronic urticaria. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:913–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber J, Shaw J, Bruce S.. Psychological components and the role of adjunct interventions in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Psychother Psychosom. 1989;51:135–141. doi: 10.1159/000288147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buske-Kirschbaum A, Geiben A, and Wermke C. et al. Preliminary evidence for herpes labialis recurrence following experimentally induced disgust. Psychother Psychosom. 2001 70:86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt DD, Schmidt PM, and Crabtree BF. et al. The temporal relationship of psychosocial stress to cellular immunity and herpes labialis recurrences. Fam Med. 1991 23:594–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surman OS, Crumpacker C.. Psychological aspects of herpes simplex virus infection: report of six cases. Am J Clin Hypn. 1987;30:125–131. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1987.10404172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz B, Loutsch JM, and Marquart ME. et al. Stress-associated immunomodulation and herpes simplex virus infection. Med Hypotheses. 2001 56:348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo D, Koehn K.. Psychosocial factors and recurrent genital herpes: a review of prediction and psychiatric treatment studies. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1993;23:99–117. doi: 10.2190/L5MH-0TCW-1PKD-5BM0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK.. Herpes zoster in the medically healthy child and covert severe child abuse. Cutis. 2000;66:221–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewin DM.. Hypnotherapy for warts (verrucae vulgaris): 41 consecutive cases with 33 cures. Am J Clin Hypn. 1992;35:1–10. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1992.10402977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanos NP, Williams V, Gewynn MI.. Effects of hypnotic, placebo and salicylic acid treatments on wart regression. Psychosom Med. 1990;52:109–114. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Ebel C, and Catotti DN. et al. The psychosocial impact of human papillomavirus infection: implications for health care providers. Int J STD AIDS. 1996 7:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS.. Dermatitis artifacta. Clinical features and approaches to treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:47–55. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabisch W.. Psychiatric aspects of dermatitis artefacta. Br J Dermatol. 1980;102:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1980.tb05668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spraker MK.. Cutaneous artefactual disease: an appeal for help. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1983;30:659–668. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimoski A, Duricic S.. Dermatitis artefacta, onychophagia and trichotillomania in mentally retarded children and adolescents. Med Pregl. 1991;44:471–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK.. Dermatitis artefacta and sexual abuse. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:825–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb02776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DPH.. Dermatitis artefacta in mother and baby as child abuse. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:199–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.143.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcolado JC, Ray K, and Baxter M. et al. Malignant change in dermatitis artefacta. Postgrad Med J. 1993 69:648–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS.. Dermatitis artefacta: clinical features and approaches to treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:47–55. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS.. Cutaneous manifestations of psychiatric disease that commonly present to the dermatologist: diagnosis and treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22:47–63. doi: 10.2190/JMLB-UUTJ-40PN-KQ3L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon I, Sneddon J.. Self-inflicted injury: a follow-up study of 43 patients. Br Med J. 1975;3:527–530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5982.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnis-Jones S, Collins S, Rosenthal D.. Treatment of self-mutilation with olanzapine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo J, Lebwohl A.. Psychodermatology: the mind and skin connection. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1873–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani JT, Flowers FP, Pierce DK.. Pimozide in delusion of parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:312–313. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80767-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann K, Avnstorp L.. Delusions of infestation treated by pimozide: a double-blind crossover clinical study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo J, Lee CS.. Delusions of parasitosis: a dermatologist's guide to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Derm. 2001;2:285–290. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon OA, Furmaga KM, and Canterbury AL. et al. Risperidone in the treatment of delusion of infestations. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997 27:403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan TN, Suresh TR, and Jayaram V. et al. Nature and treatment of delusional parasitosis: a different experience in India. Int J Dermatol. 1994 33:851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner C, DuToit PL, and Zungu-Durwayi N. et al. Childhood trauma in obsessive-compulsive disorders, trichotillomania and controls. Depress Anxiety. 2002 15:66–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D, O'Jite J, and Kennedy R. et al. Trichotillomania associated with dementia: a case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001 23:163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser S, Black DW, and Blum N. et al. The demography, phenomenology, and family history of 22 persons with compulsive hair pulling. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1994 6:147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enos S, Plante T.. Trichotillomania: an overview and guide to understanding. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2001;39:3910–3918. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-20010501-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Hermesh H, Sever J.. Hypnotherapy in adolescents with trichotillomania: three cases. Am J Clin Hypn. 2001;44:63–68. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2001.10403457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HA, Barzilai A, Lahat E.. Hypnotherapy: an effective treatment modality for trichotillomania. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:407–410. doi: 10.1080/08035259950169783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M, Moossavi M, and Ginsburg I. et al. A psychometric study of patients with nail dystrophies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 45:851–856.11712029 [Google Scholar]

- Stengler-Wenzke K, Beck M, and Holzinger A. et al. Stigma experiences of patients with obsessive compulsive disorders. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2004 72:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, O'Doherty C, and Rajagopal S. et al. How common is obsessive-compulsive disorder in a dermatology outpatient clinic? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 64:152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, and Deckersbach T. et al. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics and comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 60:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JY, Smith LL.. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in pediatric dermatology practice. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan SJ, Doherty VR.. Naevophobia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:499–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterill JA.. Dermatological non-disease: a common and potentially fatal disturbance of cutaneous body image. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:611–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Dufresne RG.. Body dysmorphic disorder: a guide for dermatologists and cosmetic surgeons. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:235–243. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Diaz SF.. Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:570–577. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS.. The dysmorphic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:780–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Dufresne RG Jr. Body dysmorphic disorder: a guide for primary care physicians. Prim Care. 2002;29:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(03)00076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy GE, Coterill JA.. A study of depression and obsessionality in dysmorphophobic and psoriatic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:19–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Taub SL.. Skin picking as a symptom of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1995;31:279–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Albertini RS, and Siniscalchi JM. et al. Effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a chart review study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62:721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger C, Rost B, Itin P.. Cutaneous manifestations in anorexia nervosa. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000;130:565–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumia R, Varotti E, and Manzato E. et al. Skin signs in anorexia nervosa. Dermatology. 2001 203:314–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorio R, Allevato M, and dePablo A. et al. Prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in 200 patients with eating disorders. Int J Dermatol. 2000 39:348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze UM, Pittke-Rank CV, and Kreienkamp M. et al. Dermatologic findings in anorexia and bulimia nervosa of childhood and adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999 16:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Habermann HF.. Dermatologic signs in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1386–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie R, Danziger Y, and Kaplan Y. et al. Acquired pili torti: a structural hair shaft defect in anorexia nervosa. Cutis. 1996 57:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Johnson AM.. Nonweight-related body image concerns among female eating-disordered patients and nonclinical controls: some preliminary observations. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27:304–309. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200004)27:3<304::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Leung CM, and Wing YK. et al. Acne as a risk factor for anorexia nervosa in Chinese. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1991 25:134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Mitchell JE, and Davis TL. et al. Long term impact of treatment in women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2002 31:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J.. A preliminary controlled evaluation of an eating disturbance: psychoeducational intervention for college students. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:159–171. doi: 10.1002/eat.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko SM.. Underdiagnosed psychiatric syndrome, 2: pathologic skin picking. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999;28:557–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calicusu C, Yucel B, and Polat A. et al. Expression of anger and alexithymia in patients with psychogenic excoriation: a preliminary report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002 32:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Habermann HF.. The self-inflicted dermatoses: a critical review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(87)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruensgaard K.. Neurotic excoriations. A controlled psychiatric examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1984;312:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp NE.. Self-caused skin ulcers. Psychosomatics. 1977;18:15–19. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(77)71084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner C, Simeon D, and Niehaus D. et al. Trichotillomania and skin picking: a phenomenological comparison. Depress Anxiety. 2002 15:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub E, Robinson C, Newmeyer M.. Catastrophic medical complication in psychogenic excoriation. South Med J. 2000;93:1099–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris BA, Sherertz EF, Flowers FP.. Improvement of chronic neurotic excoriations with oral doxepin therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:541–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi M, Arcangeli T, Petrucci RM.. Paroxetine in a case of psychogenic pruritus and neurotic excoriation. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:165–166. doi: 10.1159/000012386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS.. Stress and the skin: significance of emotional factors in dermatology. Stress Medicine. 1988;4:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Koblenzer CS. Psychological and psychiatric aspects of itching. In: Bernhard JD, ed. Itch: Mechanisms and Management of Pruritus. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, and Schork NJ. et al. Depression modulates pruritus perception: a study of pruritus, atopic dermatitis, and chronic idiopathic urticaria. Psychosom Med. 1994 56:36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett S, Ryan T.. Skin disease and handicap: an analysis of the impact of skin conditions. Soc Sci Med. 1985;20:425–429. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsarou-Katsari A, Singh LK, Theoharides TC.. Alopecia areata and affected skin CRH receptor upregulation induced by acute emotional stress. Dermatology. 2001;203:157–161. doi: 10.1159/000051732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda M, Makino T, and Kagoura M. et al. Expression of neuropeptide-degrading enzymes in alopecia areata: an immunohistochemical study. Br J Dermatol. 2001 144:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JY, Shellow WV, and Hallman C. et al. Alopecia areata and increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1994 33:849–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Hernandez MJ, Ruiz-Doblado S, and Rodriguez-Pichardo A. et al. Alopecia areata, stress and psychiatric disorders: a review. J Dermatol. 1999 26:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellow WV, Edwards JE, Koo JY.. Profile of alopecia areata: a questionnaire analysis of patient and family. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:186–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb03932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon EA, Popkin MK, and Callies AL. et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alopecia areata. Compr Psychiatry. 1991 32:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos L, Bor R, and Legg C. et al. Impact of life events on the onset of vitiligo in adults: preliminary evidence for a psychological dimension in etiology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998 23:243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer BA, Schallreuter KU.. Investigation of the personality structure in patients with vitiligo and a possible association with impaired catecholamine metabolism. Dermatology. 1995;190:109–115. doi: 10.1159/000246657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo SK, Handa S, and Kaur I. et al. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. J Dermatol. 2001 28:424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J, Beuf H, and Lerner A. et al. Response to cosmetic disfigurement: patients with vitiligo. Cutis. 1987 39:493–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J, Beuf H, and Nordlund JJ. et al. Psychological reaction to chronic skin disorders: a study of patients with vitiligo. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1979 1:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshevenko IuN.. The psychological characteristics of patients with vitiligo. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1989;5:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J, Beuf H, and Lerner AB. et al. The effect of vitiligo on sexual relationship. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990 22:221–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo J, Gambla C.. Cutaneous sensory disorder. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:497–502. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnoff OD.. Psychogenic purpura (autoerythrocyte sensitization): an unsolved dilemma. Am J Med. 1989;87:16N–21N. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer-Dubon C, Orozco-Topete R, Reyes-Gutierrez E.. Two cases of psychogenic purpura. Rev Invest Clin. 1998;50:145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo J, Gambla C, Fried R.. Pseudopsychodermatologic disease. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:525–530. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK.. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:846–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ.. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18131897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenefelt PD.. Hypnosis in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:393–398. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenefelt PD.. Biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral methods, and hypnosis in dermatology: is it all in your mind? Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:114–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8019.2003.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Ellis CN.. Antidepressant drugs in dermatology: an update. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:647–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson H, Levine N.. Neurotropic and psychotropic drugs in dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2001;19:179–197. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard MA, Fiszenson F, and Jreissati M. et al. Cutaneous adverse effects during selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors therapy: 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001 128:759–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolese HC, Chouinard G, and Beauclair L. et al. Cutaneous vasculitis induced by paroxetine. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 158:497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock JK, Morris DW.. Adverse cutaneous reactions to antidepressants. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:329–339. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Harris JC, Nousari HC.. Critical overview: adverse cutaneous reactions to psychotropic medications [CME] J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:714–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundley JL, Yosipovitch G.. Mirtazapine for reducing nocturnal itch in patients with chronic pruritus: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:889–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey BR, Glanzman RL.. Use of gabapentin for postherpetic neuralgia: result of two randomized placebo-controlled studies. Clin Ther. 2003;25:2597–2608. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HH, Wing Y, and Su R. et al. A controlled study of the cutaneous side effects of chronic lithium therapy. J Affect Disord. 2000 57:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Martin W.. Lithium carbonate and psoriasis. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:1326–1327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmanowitz VJ.. Lithium, leukocytes and lesions. Clin Dermatol. 1986;4:170–175. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(86)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockenfels HM, Wagner SM, and Keim-Maas C. et al. Lithium and psoriasis: cytokine modulation of cultured lymphocytes and psoriatic keratinocytes by lithium. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996 288:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng MC.. Lithium carbonate toxicity. Acneiform eruption and other manifestations. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:246–248. doi: 10.1001/archderm.118.4.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebrnik A, Bar-Nathan EA, and Ilie B. et al. Vaginal ulcerations due to lithium carbonate therapy. Cutis. 1991 48:65–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan KI.. Development of mucosal ulcerations with lithium carbonate therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:956–957. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.956b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Knowles SR, and Gupta MA. et al. Lithium therapy associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: case report and review of the dermatologic side effects of lithium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 32:382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin HS, Lipscombe T, and Orton DI. et al. Lithium-induced follicular hyperkeratosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996 21:296–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RD Jr, Hammer CJ, Patterson SD.. A cutaneous disorder (Darier's disease) evidently exacerbated by lithium carbonate. Psychosomatics. 1986;27:800–801. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(86)72614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DJ, Murphy F, and Burgess WR. et al. Lichenoid stomatitis associated with lithium carbonate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 13(2, pt 1):243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhold JM, West DP, and Gurwich E. et al. Cutaneous reaction to lithium carbonate: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1980 41:395–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiffers J, Dick P.. Cutaneous side-effects of treatment with lithium. Dermatologica. 1977;155:155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracious BL, Llana M, Burton DD.. Lithium and geographic tongue. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1069–1070. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis GJ, Silverman AR, and Saleh O. et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides associated with lithium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 44:308–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreno B, Moyse D.. Lithium gluconate in the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis: a multicenter, randomised, double-blind study versus placebo. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:549–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Smith RE.. Steroid-induced psychiatric syndromes. A report of 14 cases and a review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 1983;5:319–332. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(83)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CH, Tam MM, Hook SJ.. Acne, isotretinoin treatment and acute depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001;2:159–161. doi: 10.3109/15622970109026803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysowski DK, Pitts M, Beitz J.. Depression and suicide in patients treated with isotretinoin. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysowski DK, Pitts M, Beitz J.. An analysis of reports of depression and suicide in patients treated with isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:515–519. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DG, Deutsch NL, Brewer M.. Suicide, depression, and isotretinoin: is there a causal link? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:S168–S175. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.118233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jick SS, Kremers HM, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C.. Isotretinoin use and risk of depression, psychotic symptoms, suicide and attempted suicide. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1231–1236. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.10.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananth J, Ghadirian AM.. Drug-induced mood disorders. Int Pharmaco-psychiatry. 1980;15:59–73. doi: 10.1159/000468412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawkrodger D.. Manic depression induced by dapsone in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. BMJ. 1989;299:860. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6703.860-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]