Abstract

PROLACTIN IS A PITUITARY HORMONE that plays a pivotal role in a variety of reproductive functions. Hyperprolactinemia is a common condition that can result from a number of causes, including medication use and hypothyroidism as well as pituitary disorders. Depending on the cause and consequences of the hyperprolactinemia, selected patients require treatment. The underlying cause, sex, age and reproductive status must be considered. We describe the diagnostic approach and management of hyperprolactinemia in various clinical settings, with emphasis on newer diagnostic strategies and the role of various therapeutic options, including treatment with selective dopamine agonists.

Prolactin is a pituitary-derived hormone that plays a pivotal role in a variety of reproductive functions. It is an essential factor for normal production of breast milk following childbirth. Furthermore, prolactin negatively modulates the secretion of pituitary hormones responsible for gonadal function, including luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone. An excess of prolactin, or hyperprolactinemia, is a commonly encountered clinical condition.1 Management of this condition depends heavily on the cause and on the effects it has on the patient. In this review we summarize advances in our understanding of the clinical significance of hyperprolactinemia and its pathogenetic mechanisms, including the influence of concomitant medication use. Emphasis will be placed on newer diagnostic strategies and the role of various therapeutic options, including treatment with selective dopamine agonists, in various clinical settings.

Epidemiologic features

An excess of prolactin above a reference laboratory's upper limits, or “biochemical hyperprolactinemia,” can be identified in up to 10% of the population.1 Women with oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, galactorrhea or infertility, and men with hypogonadism, impotence or infertility must have serum prolactin levels measured.

The occurrence of clinically apparent hyperprolactinemia depends on the study population. The prevalence has been reported to range from 0.4% in an unselected healthy adult population in Japan to 5% among clients at a family planning clinic.1 The rate is even higher among patients with specific symptoms that may be attributable to hyperprolactinemia: it is estimated at 9% among women with amenorrhea, 25% among women with galactorrhea and as high as 70% among women with amenorrhea and galactorrhea.1 The prevalence is about 5% among men who present with impotence or infertility.1

Regulation of prolactin secretion

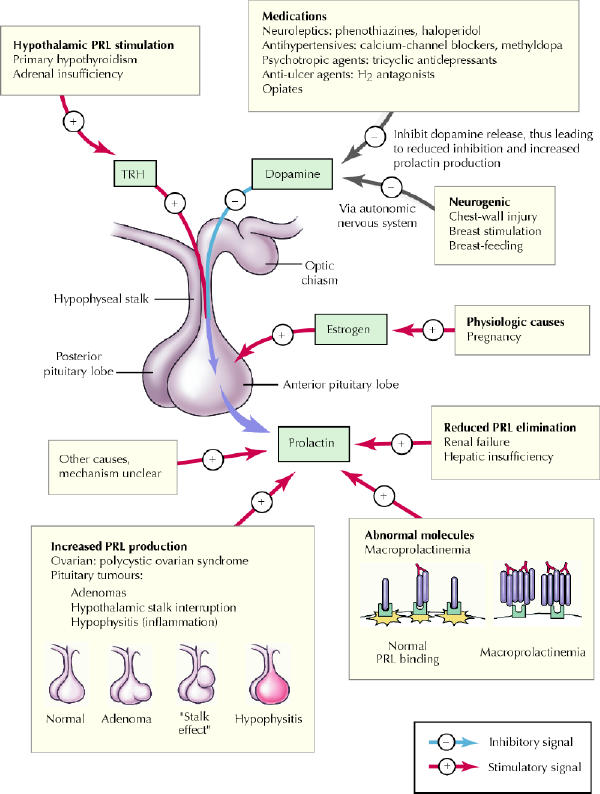

Like most anterior pituitary hormones, prolactin is under dual regulation by hypothalamic hormones delivered through the hypothalamic–pituitary portal circulation (Fig. 1). Under most conditions the predominant signal is inhibitory, preventing prolactin release, and is mediated by the neurotransmitter dopamine. The stimulatory signal is mediated by the hypothalamic hormone thyrotropin-releasing hormone. The balance between the 2 signals determines the amount of prolactin released from the anterior pituitary gland.2 Furthermore, the amount cleared by the kidneys influences the concentration of prolactin in the blood.2,3

Fig. 1: Causes of hyperprolactinemia. Prolactin (PRL) is under dual control from the hypothalamus, where dopamine serves as an inhibitory signal, preventing PRL secretion, and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), under some conditions, stimulates increased PRL production and release. Increased anterior pituitary hormone production can occur from a PRL-producing adenoma or from inflammation (hypophysitis). However, conditions that result in impaired dopamine delivery or enhanced TRH signalling, or both, will also result in increased PRL release. In general, medications result in increased PRL production through their anti-dopaminergic properties. Chest-wall injury and breast stimulation serve as peripheral triggers of autonomic control, which impinge on central neurogenic pathways that attenuate dopamine release into the hypophyseal portal circulation. In some conditions, such as renal or hepatic insufficiency, PRL is cleared less rapidly from the systemic circulation, which results in increased blood levels of PRL. Photo: Myra Rudakewich

Causes of hyperprolactinemia

The differential diagnosis and causes of pathological hyperprolactinemia are summarized in Fig. 1. The presence of a secondary cause and fluctuating degrees of hyperprolactinemia should raise the suspicion of a nontumorous cause. Consideration of such secondary contributions can obviate the need for unnecessary testing and inappropriate treatment.

Macroprolactinemia

Asymptomatic patients with intact gonadal and reproductive function and moderately elevated prolactin levels may have macroprolactinemia.3 This term should not be confused with macroprolactinoma, which refers to a large pituitary tumour greater than 10 mm in diameter. Macroprolactinemia refers to a polymeric form of prolactin in which several prolactin molecules form a polymer that is recognized by immunologically based serum assays. In general, macroprolactin results from the binding of prolactin to IgG antibodies. The large prolactin polymer is unable to interact with the prolactin receptor. Little, if any, biological effect of prolactin excess is noted. If macroprolactinemia is suspected, the laboratory should be notified, and the specimen can be subjected to polyethylene glycol precipitation before assessment.3 If macroprolactinemia accounts for most of the prolactin excess, no specific treatment is needed.

Hypothyroidism

The hyperprolactinemia of hypothyroidism is related to several mechanisms. In response to the hypothyroid state, a compensatory increase in the discharge of central hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone results in increased stimulation of prolactin secretion.2 Furthermore, prolactin elimination from the systemic circulation is reduced, which contributes to increased prolactin concentrations.2 Primary hypothyroidism can be associated with diffuse pituitary enlargement, which will reverse with appropriate thyroid hormone replacement therapy.2

Pituitary tumours

Pituitary tumours are common neoplasms that exhibit a wide range of biological behaviour, as evidenced by hormonal and proliferative activities.2 Among pituitary adenomas, prolactin-producing pituitary tumours are the most common type. About one-third of all pituitary tumours are not associated with hypersecretory syndromes but, rather, present with symptoms of an intracranial mass, such as headaches, nausea, vomiting or visual field disturbances. Because of suprasellar extension, pituitary tumours may interrupt dopamine delivery from the hypothalamus to the pituitary, resulting in loss of inhibition of prolactin release, or the “stalk effect.” In contrast, tumours that produce growth hormone (GH) may also secrete prolactin in nearly 25% of cases.2 This is a common source of misdiagnosis, as the features of prolactin excess may capture attention while the more subtle features of GH excess go unnoticed. In both cases the distinction is important. Surgery is indicated for a nonfunctional pituitary adenoma that is large enough to cause the stalk effect. For tumours that are secreting both GH and prolactin, therapy with GH-inhibitory agents is the preferred treatment in most cases. Finally, an autoimmune condition of the pituitary with lymphocytic infiltration can lead to hyperprolactinemia.4 This form of lymphocytic hypophysitis is typically noted in the postpartum phase in women of childbearing age. Surgery is rarely indicated, and spontaneous resolution is common.4

Clinical presentations

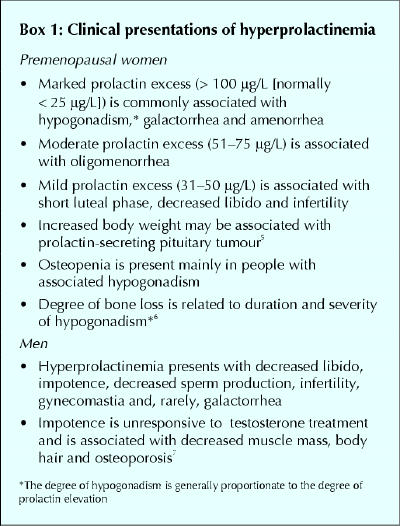

The clinical manifestations of prolactin excess (Box 1) can be divided into 2 main categories: those that are mediated by prolactin excess directly and those representing the consequences of the resulting hypogonadism.

Box 1.

Diagnosis

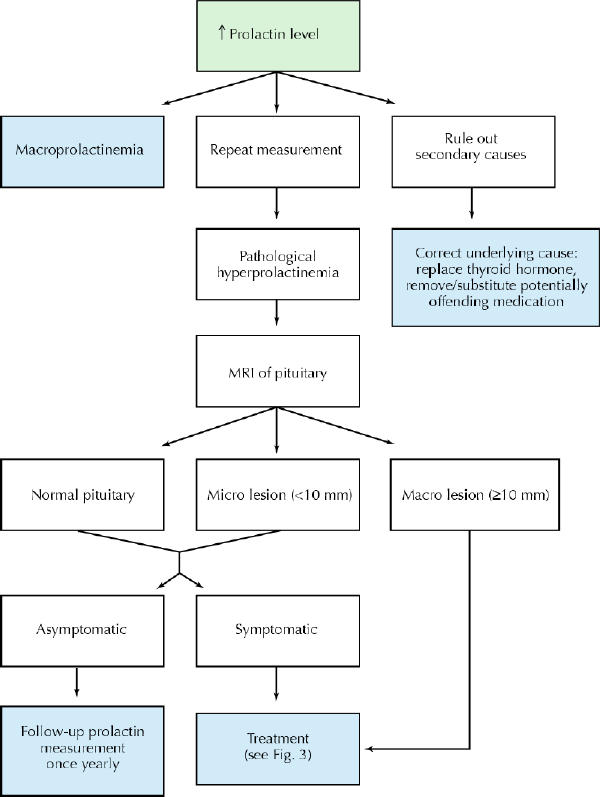

The evaluation is aimed at excluding physiologic, pharmacologic or other secondary causes of hyperprolactinemia (Fig. 1). In the absence of such causes, imaging (preferably MRI) of the pituitary fossa is recommended to establish whether a prolactin-secreting pituitary tumour or other lesion is present. CT scanning may not be sensitive enough to identify small lesions or large lesions that are isodense with surrounding structures. Whereas serum prolactin levels between 20 and 200 μg/L can be found in patients with hyperprolactinemia due to any cause, prolactin levels above 200 μg/L usually indicate the presence of a lactotroph adenoma. In general, there is a relatively linear relation between the degree of prolactin elevation and the size of a true prolactinoma. If a patient with only a mildly elevated serum prolactin level has a pituitary macroadenoma, the diagnosis is more likely to be a non-prolactin-producing pituitary adenoma or other sellar mass causing the stalk effect. The approach to the diagnosis of hyperprolactinemia is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2: Approach to diagnosis of hyperprolactinemia.

Natural history

Several series of patients with prolactin-secreting microadenomas observed for long periods without treatment have shown that the risk of progression to macroadenoma over 10 years is small (about 7%).8 In some cases, prolactin levels returned to normal in patients who did not receive treatment or who received treatment intermittently with dopamine agonists. Women with prolactin-secreting microadenomas who became pregnant during this interval had a higher rate of remission than women who did not become pregnant (35% v. 14%).

Management

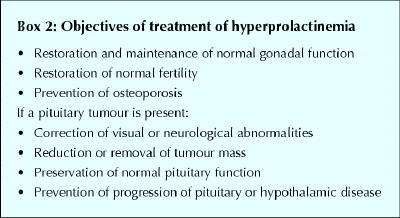

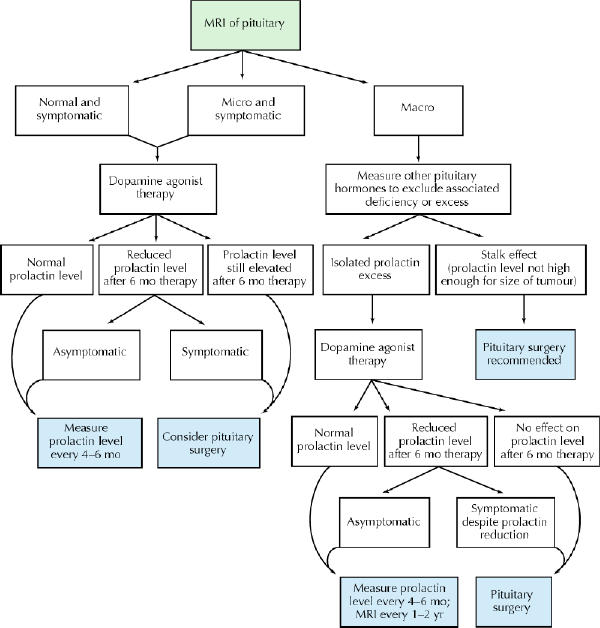

The objective of hyperprolactinemia treatment is to correct the biochemical consequences of the hormonal excess (Box 2). When present, the compressive features of a large (macro) tumour must also be alleviated and the tumour prevented from regrowing. The approach to the management of hyperprolactinemia is summarized in Fig. 3.

Box 2.

Fig. 3: Approach to management of hyperprolactinemia.

Medical therapy

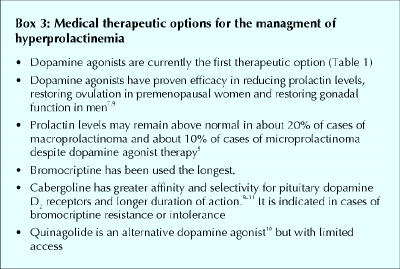

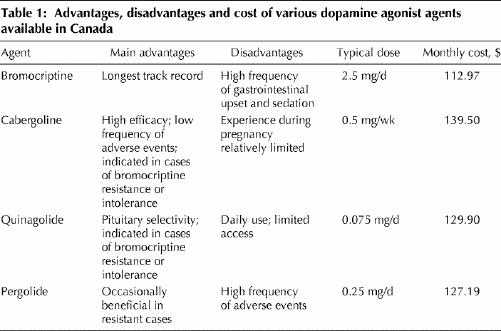

Medical therapy has traditionally involved agonists of the physiologic inhibitor of prolactin, dopamine (Box 3, Table 1). Although initially it was thought that patients would require dopamine agonist therapy all their lives, the current use of these agents has evolved into a dynamic process depending on the patient's needs and circumstances.

Box 3.

Table 1

Surgical therapy

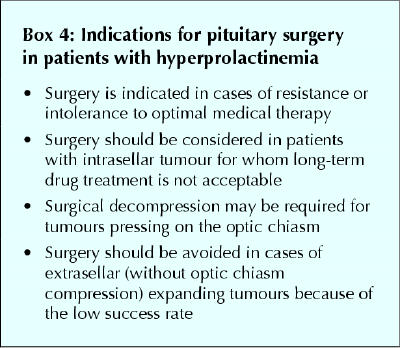

Surgical removal of tumours associated with prolactin excess requires careful consideration of treatment objectives (Box 4). It is indicated in patients with nonfunctional pituitary adenomas or other nonlactotroph adenomas associated with hyperprolactinemia and in patients in whom medical therapy has been unsuccessful or poorly tolerated.

Box 4.

The best results with transsphenoidal resection of the prolactinoma are limited to centres that have the greatest experience. In one study, the apparent surgical cure rate for prolactinomas, although good in the short term, decreased on re-evaluation during long-term follow-up.12 Hyperprolactinemia recurred within 5 years after surgery in about 50% of patients with microprolactinomas who were initially thought to be cured.12 In other series, the rate of recurrence of hyperprolactinemia following initial cure by surgery ranged from 20% to 40%.13 However, recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after surgery is not necessarily a permanent feature and does not inevitably indicate operative failure.13,14 Re-evaluation of long-term results indicates a success rate of about 75% for surgical removal of microprolactinoma. However, the results of surgery for macroprolactinoma are poor, with a long-term success rate of only 26%.13

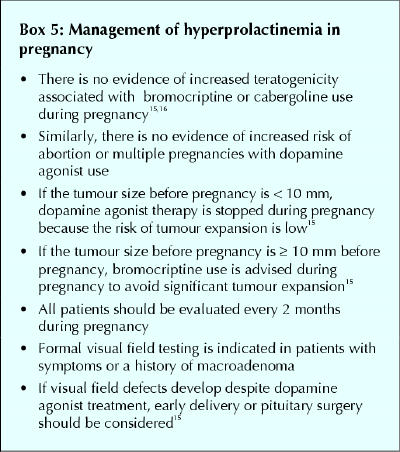

Management of hyperprolactinemia in pregnancy

The collaboration of various specialists, including an obstetrician, is required for the careful planning of pregnancy in women with hyperprolactinemia (Box 5). Ideally, this should occur before conception, to permit a full assessment of the risks and benefits of dopamine agonist therapy during pregnancy.

Box 5.

Monitoring and follow-up

Biochemical and clinical improvements in response to dopamine agonist therapy are readily apparent in most patients. In addition, tumour shrinkage can be expected in about 80% of macroadenomas.17 However, a major drawback of medical therapy is the potential need for lifelong treatment. Discontinuation of bromocriptine therapy has been shown to lead to recurrence of hyperprolactinemia in most patients and to tumour regrowth if treatment duration has been less than 2 years.18 Passos and associates18 reported maintenance of normal prolactin levels and absence of adenoma re-expansion after withdrawal of dopamine agonist therapy in 6.6% to 37.5% of patients. Recurrence usually occurs within months after drug withdrawal. These authors also reported reduced and normal prolactin levels after pregnancy in women who had prolactinomas treated with dopamine agonists. Menopause has also been suggested as a factor that increases the probability of maintaining normoprolactinemia after dopamine agonist therapy is stopped.18 Unless there is evidence of growth of a prolactinoma or related symptoms, such as headache, there is no indication to continue dopamine agonist therapy after menopause.18 There are no significant differences in age, sex, initial dopamine agonist dose or length of treatment between those with continued normoprolactinemia and those with recurrence of hyperprolactinemia.18 We suggest that the dopamine agonist dose be decreased after 2 or 3 years of normal prolactin levels and that therapy be stopped if the prolactin levels remain unchanged after 1 year at the reduced dose. The dose can be reduced by half over the course of 3 months while prolactin levels are measured monthly. After complete discontinuation of treatment, regular monitoring of clinical symptoms and prolactin levels is recommended. Given the propensity for early recurrence, prolactin levels should be measured monthly for the first 3 months and every 6 months thereafter.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the conception and design of the paper, review of the data and drafting of the manuscript. Drs. Ezzat and Serri were responsible for editing the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors received an unrestricted educational grant from Paladin Labs Inc.

Correspondence to: Dr. Shereen Ezzat, Mount Sinai Hospital, Ste. 437, 600 University Ave., Toronto ON M5G 1X5; fax 416 586-8834; sezzat@mtsinai.on.ca

References

- 1.Josimovich JB, Lavenhar MA, Devanesan MM, Sesta HJ, Wilchins SA, Smith AC. Heterogeneous distribution of serum prolactin values in apparently healthy young women, and the effects of oral contraceptive medication. Fertil Steril 1987;47:785-91. [PubMed]

- 2.Asa SL, Ezzat S. The pathogenesis of pituitary tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2: 836-49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Vallette-Kasic S, Morange-Ramos I, Selim A, Gunz G, Morange S, Enjalbert A, et al. Macroprolactinemia revisited: a study on 106 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:581-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Thodou E, Asa SL, Kontogeorgos G, Kovacs K, Horvath E, Ezzat S. Clinical case seminar: lymphocytic hypophysitis: clinicopathological findings. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:2302-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Yermus R, Ezzat S. Does normalization of prolactin levels result in weight loss in patients with prolactin secreting pituitary adenomas? [letter] Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;56:562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Biller BMK, Baum HB, Rosenthal DI, Saxe VC, Charpie PM, Klibanski A. Progressive trabecular osteopenia in women with hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:692-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Di Somma C, Colao A, Di Sarno A, Klain M, Landi ML, Facciolli G, et al. Bone marker and bone density responses to dopamine agonist therapy in hyperprolactinemic males. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:807-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Schlechte J, Dolan K, Sherman B, Chapler F, Luciano A. The natural history of untreated hyperprolactinemia: a prospective analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1989;68:412-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Cappabianca P, Di Salle F, Rossi FW, Pivonello R, et al. Resistance to cabergoline as compared with bromocriptine in hyperprolactinemia: prevalence, clinical definition and therapeutic strategy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:5256-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.De Luis DA, Becerra A, Lahera M, Botella JI, Valero, Varela C. A randomized cross-over study comparing cabergoline and quinagolide in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic patients. J Endocrinol Invest 2000;23:428-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jeffcoate WJ, Pound N, Sturrock NDC, Lambourne J. Long-term follow-up of patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:299-303. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Serri O, Rasio E, Beauregard H, Hardy J, Somma M. Recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after selective transsphenoidal adenomectomy in women with prolactinoma. N Engl J Med 1983;309:280-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Serri O, Hardy J, Massoud F. Relapse of hyperprolactinemia revisited. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Thompson JA, Gray CE, Teasdale GM. Relapse of hyperprolactinemia after transsphenoidal surgery for microprolactinoma: lessons from long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery 2002;50:36-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Molitch ME. Management of prolactinomas during pregnancy. J Reprod Med 1999;44:1121-6. [PubMed]

- 16.Ricci E, Parazzini F, Motta T, Ferrari CI, Colao A, Clavenna A, et al. Pregnancy outcome after cabergoline treatment in early weeks of gestation. Reprod Toxicol 2002;16:791-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Webster J, Piscitelli G, Polli A, Ferrari CI, Ismail I, Scanlon MF, for the Cabergoline Comparative Study Group. A comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med 1994;331:904-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Passos VQ, Souza JJ, Musolino NR, Bronstein MD. Long-term follow-up of prolactinomas: normoprolactinemia after bromocriptine withdrawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:3578-82. [DOI] [PubMed]