Historically, a major focus of behavioral neuroscience has been to understand learning and memory at systems, cellular, and molecular levels. Specifically, how does experience shape the nervous system such that subsequent behavioral responses reflect those past experiences? A critical tool in the search for neural mechanisms of learning and memory is an appropriate, effective behavioral model. One behavioral model that has proven useful for identifying circuit, cellular, and now molecular mechanisms of learning is early olfactory associative learning, a form of mammalian olfactory imprinting. In this issue of Learning & Memory, Yuan et al. (2003) make use of the many advantages of the early olfactory learning paradigm to shed light on the underlying molecular events that occur within the olfactory bulb and support this type of associative learning.

Early olfactory associative learning is a form of rapid classical conditioning in neonatal rats, wherein an odorant conditioned stimulus is temporally paired with one of a myriad of potential unconditioned stimuli (UCS) (e.g., milk, tactile stimulation, electric-shock, electrical or chemical stimulation of defined brain regions) to produce conditioned responses to the odorant. Learned behaviors include conditioned behavioral activation and approach responses to the conditioned stimulus (CS) odor. The conditioned behavioral activation can be readily assessed during training to quantify acquisition, and the learned approach responses, which can be recalled several days after training, can be assessed and quantified in Y-maze or two odor choice tests. Early olfactory learning is generally robust and given the classical conditioning nature of the paradigm, appropriate controls can be easily included to determine the role of simple odorant exposure, random CS–UCS pairings, etc. Importantly, the learning induced by this paradigm models events that occur within the nest situation as a pup learns the maternal odors necessary for nipple attachment and approach to the mother. Thus, early olfactory learning must occur for the pup to survive to weaning, and consequently, dissecting its neural mechanisms provides a window into processes under strong evolutionary control. Therefore, despite expressing several characteristics unique to the developing animal (Sullivan 2001), understanding the neurobiology of early olfactory learning could provide important in-sight into mechanisms of learning and memory conserved throughout the lifespan, as well as across species.

A particular strength of the early olfactory learning paradigm, and one taken full advantage of by Yuan et al. (2003) in their work presented here, is its dependence on a relatively reduced neural circuitry. While olfactory memory in adults is associated with changes in the hippocampus (Staubli et al. 1986; Alvarez et al. 2002), amygdala (Rosenkranz and Grace 2002; Tronel and Sara, 2002), piriform cortex (Roman et al. 1987; Litaudon et al. 1997; Zinyuk et al. 2001; Saar et al. 2002), perirhinal cortex (Herzog and Otto 1998), and orbitofrontal cortex (Ramus and Eichenbaum, 2000; Rolls 2001) among elsewhere, many of these structures are not anatomically mature or effectively activated by odors during the first postnatal week in the rat. Early olfactory learning (during the first postnatal week) is dependent on changes that occur within the olfactory bulb itself, and those changes in turn require noradrenergic (NE) input from the locus coeruleus for their acquisition (Sullivan et al. 1989, 2000), but not expression (Sullivan and Wilson 1991b).

Previous work on early olfactory learning has demonstrated that several changes occur in the neonatal olfactory bulb (Wilson and Sullivan 1994). For example, pairing an odor with a UCS reduces habituation of mitral-cell odor responses during training (Wilson and Sullivan 1992), and produces an odor-specific, long-term change in spatio-temporal output patterns of mitral cells, primarily expressed as enhanced probability of inhibitory responses to the learned odor (Wilson and Leon 1988). These effects are strongly correlated with learned behavioral performance, including a necessary and sufficient role of NE for induction (Sullivan et al. 1989), and reversal with extinction training (Sullivan and Wilson 1991a). We have proposed that this change in olfactory bulb output is because of a change in the mitral-cell–granule-cell dendrodendritic reciprocal synapse, either on the mitral-cell or granule-cell side of the synapse, producing odor-specific, localized changes in lateral and feedback inhibition of mitral cells (Wilson and Sullivan 1994). Decoding of this learned change for behavioral expression then presumably occurs in olfactory bulb target structures such as the anterior olfactory nucleus and/or piriform cortex. Learning-associated changes also occur in the glomerular layer (Leon 1987), and could reflect changes in intraglomerular synaptic strength and/or anatomical reorganization (Woo and Leon 1991; Johnson et al. 1995). The learned changes in mitral-cell output patterns and the modified balance of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic activity within the olfactory bulb are similar to learned changes in the accessory olfactory bulb and main olfactory bulb during learning of mate or offspring odors in mature mice and sheep, respectively (Brennan and Keverne 1997).

The molecular mechanisms involved in producing these changes in olfactory circuit function have only recently begun to be addressed (e.g., McLean et al. 1999; Zhang et al. in press), but a significant step forward in this regard is taken with the work of Yuan et al. (2003).

A critical clue as to the underlying molecular events of learned olfactory bulb changes came from previous work by the Harley and McLean group, which showed that, in addition to the basic locus coeruleus-olfactory bulb circuit, an important interaction occurs between norepinephrine and serotonin within the olfactory bulb during early learning (Langdon et al. 1997). It is this interaction that is the focus of the work described in this issue. Activation of olfactory bulb NE β-receptors with isoproterenol paired with odor stimulation produces a learned-approach response in rat pups (Sullivan and Wilson 1994; Sullivan et al. 2000b). The isoproterenol effect displays an inverted-U shaped dose-response curve (Sullivan et al. 1989, 1991). Harley and McLean have previously demonstrated that the isoproterenol dose-response curve can be shifted with manipulations of olfactory bulb 5-HT activity. Lesions of 5-HT fibers within the olfactory bulb shifts the isoproterenol curve to the right (higher isoproterenol doses are required to support learning; Langdon et al. 1997), while 5-HT2a/2c receptor agonists can shift the isoproterenol curve to the left (lower isoproterenol doses support learning), although 5-HT is not sufficient to support learning itself (Price et al. 1998).

The 5-HT/NE interaction led Yuan et al. (2003) to the hypothesis that cAMP levels in mitral cells are elevated by convergence of glutamatergic olfactory nerve input to mitral cells signaling the odor CS and NE/5-HT input to mitral cells signaling the UCS. They further hypothesize that the elevated cAMP levels increase cAMP response element binding (protein) (CREB) phosphorylation and lead to changes in protein synthesis that allow a long-term trace of the CS–UCS association to form in mitral cells, ultimately expressed as the learned changes in mitral-cell odor response patterns described above.

To test this hypothesis, Yuan et al. (2003) utilized a three-prong approach. First, using immunofluorescent double-labeling techniques, Yuan et al. confirmed that mitral and tufted cells in neonatal and older animals express both β1-adrenoceptors and 5-HT2A receptors, thus providing a site of convergence between NE and 5-HT on mitral cells. Second, using a cAMP assay, they confirmed that UCS’s effective at producing behavioral learning (tactile stimulation or moderate levels of isoproterenol) elevated olfactory-bulb cAMP levels, while ineffective UCS’s (too low or too high levels of isoproterenol, or 5-HT lesions) do not elevate cAMP levels. The stimuli ineffective at elevating cAMP are perhaps the more interesting, as they not only correlate cAMP levels well with behavior, but also suggest a possible mechanism for the inverted-U shaped dose-response curve. Inverted-U shaped dose-response curves are ubiquitous in the pharmacology of memory literature, yet few convincing data exist to suggest a cellular mechanism. Yuan et al.’s findings suggest that there is a limited window of β1-adrenoceptor and/or 5-HT2A receptor activation that will elevate cAMP levels in mitral cells; receptor activation above or below that level fails to raise cAMP. Finally, Yuan et al. directly quantified cAMP levels in the mitral-cell layer using optical densitometry of cAMP immunocytochemical staining. They find that isoproterenol paired with odor stimulation significantly increases cAMP staining in the mitral-cell layer compared to pups not injected with isoproterenol and that this elevation can be prevented by lesions of olfactory bulb 5-HT fibers.

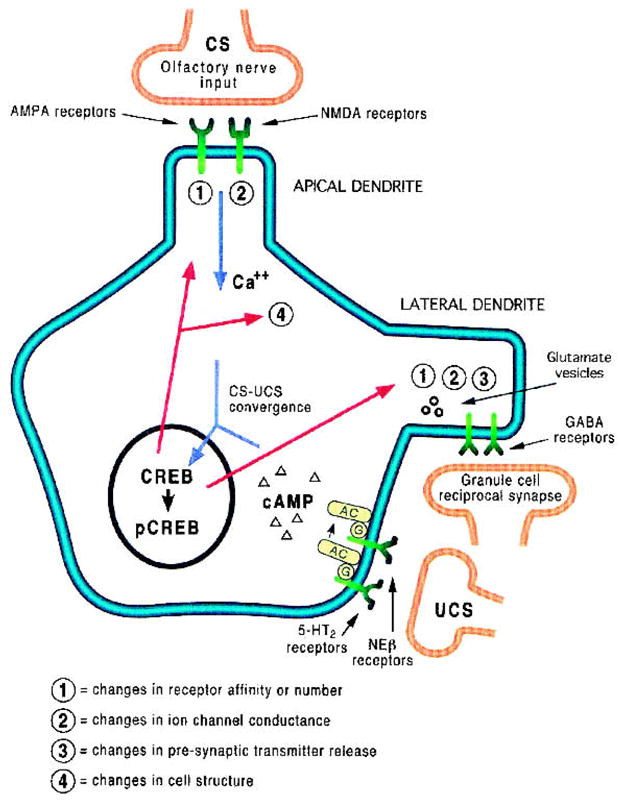

Together, these findings suggest a critical role for mitral-cell cAMP elevation in early olfactory learning. Elevation in cAMP can contribute to enhanced phosphorylation of CREB, also known to occur in early olfactory learning (McLean et al. 1999), and thus to a variety of reported changes in mitral-cell and olfactory-bulb circuit physiology (Fig. 1). These could include changes at either the olfactory nerve-mitral cell synapse (perhaps enhancing excitation of a small number of localized mitral cells and producing a corresponding increase in inhibitory surround) or in the mitral-cell–granule-cell reciprocal synapse (directly producing changes in lateral and/or feedback inhibition). The underlying synaptic changes could include either changes in neurotransmitter receptor expression or sensitivity, changes in mitral-cell transmitter release at axonal or dendritic presynaptic terminals, or even dendritic structural changes (Kandel 2001).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of molecular biology of early olfactory learning based on the data by Yuan et al. (2003) and previous work. Olfactory nerve input carrying CS information activates NMDA and AMPA receptors on the apical dendritic tuft, depolarizing the mitral cell and allowing Ca++ influx in the apical dendrite and soma, as well as in the lateral dendrites via back propagation (Lowe 2001; Margrie et al. 2001). If the odor is paired with an unconditioned stimuli (UCS), activation of NE β-receptors and 5-HT2 receptors increases cAMP levels, which combined with the high levels of Ca++, activates a cascade resulting in pCREB-mediated changes in gene transcription. Based on work in other systems (Kandel 2001) and on known learned changes in mitral-cell odor response patterns (Wilson and Sullivan 1994), the long-term downstream consequences could include (1) changes in receptor affinity or number at olfactory nerve synapses and/or granule-cell reciprocal synapses; (2) changes in ion-channel conductances; (3) changes in presynaptic transmitter release at dendrodendritic synapses affecting lateral/feedback inhibition and/or lateral/feedback excitation (Isaacson 1999; Didier et al. 2001). These changes in release could also extend to axo-dendritic synapses in mitral-cell target structures. Finally, (4) changes in cell structure including changes in apical or lateral dendritic anatomy could occur. Any or a combination of these changes could result in odor-specific changes in mitral-cell odor coding that would reflect the learned significance of the odor to the animal.

As noted by Yuan et al. (2003), the molecular mechanisms emerging for early olfactory learning and the list of potential resulting cellular changes are reminiscent of findings in several other systems ranging from the Aplysia abdominal ganglion to the mammalian hippocampus, where direct or indirect sensory input combined with appropriate levels of monoaminergic input (5-HT in Aplysia, perhaps DA or NE in hippocampus) initiate a cAMP cascade that ultimately contributes to long-term changes in cell function (for review, see Kandel 2001). Thus, while the circuits and stimuli involved in olfactory memory may change over ontogeny (Sullivan 2001; Sullivan et al. 2000a), the intracellular mechanisms may not. This suggests that the molecular biology underlying storage of critical memories in the central nervous system is highly conserved across both development and species.

Acknowledgments

R.M.S. was supported by NSF IBN0117234 and NIH NICHD HD33402. D.A.W. was supported by NSF IBN9808149 and NIH NIDCD DC003906. We thank Coral McCallister for figure preparation.

References

- Alvarez P, Wendelken L, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampal formation lesions impair performance in an odor-odor association task independently of spatial context. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:470–476. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PA, Keverne EB. Neural mechanisms of mammalian olfactory learning. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;51:457–481. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier A, Carleton A, Bjaalie JG, Vincent JD, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Lledo PM. A dendro-dendritic reciprocal synapse provides a recurrent excitatory connection in the olfactory bulb. PNAS. 2001;98:6441–6446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101126398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog C, Otto T. Contributions of anterior perirhinal cortex to olfactory and contextual fear conditioning. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1855–1859. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806010-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS. Glutamate spillover mediates excitatory transmission in the rat olfactory bulb. Neuron. 1999;23:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Woo CC, Duong H, Nguyen V, Leon M. A learned odor evokes an enhanced Fos-like glomerular response in the olfactory bulb of young rats. Brain Res. 1995;699:192–200. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: A dialogue between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294:1030–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon PE, Harley CW, McLean JH. Increased β adrenoceptor activation overcomes conditioned olfactory learning deficits induced by serotonin depletion. Dev Brain Res. 1997;102:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon M. Plasticity of olfactory output circuits related to early olfactory learning. TINS. 1987;10:434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Litaudon P, Mouly AM, Sullivan R, Gervais R, Cattarelli M. Learning induced changes in rat piriform cortex activity mapped using multisite recording with voltage sensitive dye. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:1593–1603. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe G. Inhibition of backpropagating action potentials in mitral cell secondary dendrites. J Neurophysiol. 2001;88:64–85. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margrie TW, Sakman B, Urban NN. Action potential propagation in mitral cell lateral dendrites is decremental and controls recurrent and lateral inhibition in the mammalian olfactory bulb. PNAS. 2001;98:319–324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011523098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JH, Harley CW, Darby-King A, Yuan Q. pCREB in the neonate rat olfactory bulb is selectively and transiently increased by odor preference-conditioned training. Learn Mem. 1999;6:608–618. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.6.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TL, Darby-King A, Harley CW, McLean JH. Serotonin plays a permissive role in conditioned olfactory learning induced by norepinephrine in the neonate rat. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1430–1437. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramus SJ, Eichenbaum H. Neural correlates of olfactory recognition memory in the rat orbitofrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8199–8208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The rules of formation of the olfactory representations found in the orbitofrontal cortex olfactory areas in primates. Chem Senses. 2001;26:595–604. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.5.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman F, Staubli U, Lynch G. Evidence for synaptic potentiation in cortical network during learning. Brain Res. 1987;418:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz JA, Grace AA. Dopamine-mediated modulation of odour-evoked amygdala potentials during Pavlovian conditioning. Nature. 2002;417:282–287. doi: 10.1038/417282a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saar D, Grossman Y, Barkai E. Learning-induced enhancement of postsynaptic potentials in pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2358–2363. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staubli U, Fraser D, Kessler M, Lynch G. Studies on retrograde and anterograde amnesia of olfactory memory after denervation of the hippocampus by entorhinal cortex lesions. Behav Neural Biol. 1986;46:432–444. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(86)90464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM. Unique characteristics of neonatal classical conditioning: The role of the amygdala and locus coeruleus. Integ Physiol Behav Sci. 2001;36:293–307. doi: 10.1007/bf02688797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Wilson DA. Neural correlates of conditioned odor avoidance in infant rats. Behav Neurosci. 1991a;105:307–312. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Wilson DA. The role of norepinephrine in the expression of learned olfactory neurobehavioral responses in infant rats. Psychobiol. 1991b;19:308–312. doi: 10.3758/bf03332084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Wilson DA. The locus coeruleus, norepinephrine, and memory in newborns. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35:467–472. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Wilson DA, Leon M. Norepinephrine and learning-induced plasticity in infant rat olfactory system. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3998–4006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03998.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, McGaugh JL, Leon M. Norepinephrine-induced plasticity and one-trial olfactory learning in neonatal rats. Dev Brain Res. 1991;60:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90050-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Landers M, Yeaman B, Wilson A. Good memories of bad events in infancy. Nature. 2000a;407:38–39. doi: 10.1038/35024156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Stackenwalt G, Nasr F, Lemon C, Wilson DA. Association of an odor with activation of olfactory bulb noradrenergic β-receptors or locus coeruleus stimulation is sufficient to produce learned approach responses to that odor in neonatal rats. Behav Neurosci. 2000b;114:957–962. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.114.5.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronel S, Sara SJ. Mapping of olfactory memory circuits: Region-specific c-fos activation after odor-reward associative learning or after its retrieval. Learn Mem. 2002;9:105–111. doi: 10.1101/lm.47802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DA, Leon M. Spatial patterns of olfactory bulb single-unit responses to learned olfactory cues in young rats. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1770–1782. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.6.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DA, Sullivan RM. Blockade of mitral/tufted cell habituation to odors by association with reward: A preliminary note. Brain Res. 1992;594:143–145. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91039-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DA, Sullivan RM. Neurobiology of associative learning in the neonate: Early olfactory learning. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CC, Leon M. Increase in a focal population of juxtaglomerular cells in the olfactory bulb associated with early learning. J Comp Neurol. 1991;305:49–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.903050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Harley CW, McLean JH. Mitral cell β1 and 5-HT2A receptor colocalization and cAMP coregulation: A new model of norepinephrine-induced learning in the olfactory bulb. Learn Mem. 2003 doi: 10.1101/lm.54803. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JJ, Okutani F, Inoue S, Kaba H. Activation of the cyclic AMP response element-binding protein signaling pathway in the olfactory bulb is required for the acquisition of olfactory aversive learning in young rats. Neurosci. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00962-4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinyuk LE, Datiche F, Cattarelli M. Cell activity in the anterior piriform cortex during an olfactory learning in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2001;124:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]