Abstract

Norepinephrine is supplied to both deep and superficial layers of the olfactory bulb through dense projections from the locus coeruleus.16 Beta-adrenergic receptors are located in nearly all bulb laminae, with high-density foci of β-1 and β-2-adrenoceptors present in the glomerular layer.29 Early olfactory experiences that increase norepinephrine levels in the bulb also decrease the density of β-1- and β-2-adrenoceptors, as well as the number of high-density glomerular foci of β-2-receptors.30 Changes in bulb norepinephrine levels, therefore, may affect the density of β-adrenoceptors in the bulb. In the current study, we test this hypothesis by performing unilateral lesions of the locus coeruleus with 6-hydroxydopamine on postnatal day 4, and examining the density of β-1- and β-2-adrenergic receptors in the main olfactory bulb of the rat using 125I-labeled iodopindolol receptor autoradiography on postnatal day 19. Locus coeruleus destruction resulted in a statistically significant increase in the density of adrenergic receptors in the ipsilateral bulb compared to the contralateral bulb. Both β-1- and β-2-adrenoceptor subtypes increased in density with this manipulation, although the number of glomerular layer high-density β-2 foci was not significantly different between the two bulbs. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that changes in olfactory bulb norepinephrine can regulate the density of β-adrenergic receptors in the bulb.

Keywords: 6-hydroxydopamine, 125I-iodopindolol, receptor autoradiography, olfaction

The main olfactory bulb of the rat receives a major projection from the locus coeruleus, which provides norepinephrine to the bulb.16 Locus coeruleus fibers in the bulb are present by postnatal day (PND) 1, and increase in density with age.15 These centrifugal fibers project predominantly to the deeper layers of the bulb, with some fibers extending to the more superficial glomerular layer,16 thereby supplying norepinephrine to both deep and superficial layers of the bulb.10,17

Norepinephrine levels increase in the bulb during early olfactory preference training,21 and is necessary for the acquisition of early olfactory learning.23,24 Locus coeruleus lesions resulting in an 83-91% reduction of norepinephrine in the bulb can block early olfactory preference learning,26 and such learning can be attenuated with either a systemic or an intrabulbar injection of a β-adrenergic antagonist prior to early olfactory training.25,27 In contrast, systemic injections of an α-antagonist do not appear to affect this early learning (Woo et al., unpublished observations), despite a high density of alpha receptors in the bulb.12

β-1- and β-2-Adrenergic receptors are present in both deep and superficial layers of the bulb, and increase in density with age.17,19,29 Within the glomerular layer, there are focal regions exhibiting high densities of β-1- and β-2-receptors that correspond to the neuropil of individual glomeruli.29,30 The glomerular β-1-receptors are present in most glomeruli, whereas the glomerular β-2-receptors are present in only a subset of the glomeruli. The high-density β-2-receptor foci in the glomerular layer have approximately 50% more iodopindolol binding than adjacent glomerular regions.30 The glomerular location of these β-receptor foci is intriguing, especially since the first synapse between the olfactory receptor neurons and olfactory bulb neurons are made within glomeruli after the first postnatal week. It is possible, therefore, that norepinephrine could modulate neural activity in the main olfactory bulb, even at the level of the first synaptic contacts.

Early olfactory experiences can affect the distribution and density of β-adrenergic receptors in the main olfactory bulb. Early olfactory deprivation, as well as early olfactory preference training, decreases the density of β-2-adrenergic receptors and the number of β-2 glomerular foci in the bulb.30 The decreased density of β-adrenergic receptors observed with these olfactory experiences could be a response to the transient increase in norepinephrine measured in the bulb following both manipulations.4,21,28

In other brain regions, noradrenergic agonists have been shown to down-regulate, and antagonists to up-regulate, β-adrenergic receptor density.3,5,6 In addition, depletion of norepinephrine by lesioning of the locus coeruleus results in an increase in the density of adrenergic receptors in a number of brain regions.2,7,8,11 To address the possibility that changes in the level of bulb norepinephrine could impact the density of β-adrenergic receptors in the olfactory bulb, we performed early unilateral locus coeruleus lesions, using 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), and examined the density of β-adrenergic receptors in the main olfactory bulb.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Locus coeruleus lesions were performed at the University of Oklahoma (Norman, OK), in a manner similar to that reported previously.26 On PND 4, male Wistar rat pups (Hilltop Farms, PA) were cold-anesthetized, placed in a stereotaxic apparatus, and bilateral holes were drilled in the skull above the locus coeruleus (caudal − 1.40 mm; lateral ±0.60 mm from lambda). A 30-gauge cannula attached to a 10 μl syringe was lowered 5.50 mm from the surface of the skull, and 0.5 μl of 6-OHDA (4 mg/ml in saline) was delivered slowly by lightly depressing the syringe plunger. After 30 sec, an additional 0.5 μl was infused, for a total volume of 1.0 μl of infusate. This procedure was repeated for the contralateral side with saline as the infusate, or with no infusion. The scalp was closed with cyanoacrylate (Krazy Glue, Borden) and the pup was placed on a heating pad (32°C) for 1 hr, then returned to the dam. On PND 19, pups were decapitated quickly and brains were removed, frozen by immersion in 2-methylbutane (−45°C) and stored at −70°C.

Brains then were shipped on dry ice to the University of California, Irvine, where receptor binding and immunostaining procedures were performed. Coronal, 20 μm cryostat sections were taken through the olfactory bulbs, thaw-mounted onto gelatin-subbed slides, and stored at −20°C. Alternate sections were collected for total binding, non-specific binding, β-1 binding, β-2 binding, or dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) immunostaining, respectively. The distance between sections used for any individual condition was 100 μm.

β-Adrenergic receptor binding

Receptor-binding procedures were done as described in Woo and Leon,29 following the protocols of Joyce et al.,13 and Rainbow et al.,20 with some modifications. Briefly, slides were incubated with 125I-iodopindolol (New England Nuclear; 200 pM in 20 mM Tris-HCl and 135 mM NaCl) for 70 min at 22°C. Either the specific β-1-antagonist ICI 89,406 (70 nM) or the specific β-2-antagonist ICI 118,551 (100 nM) was included in the incubation to visualize β-2- and β-1-receptors, respectively, and isoproterenol (100 μM) was used to define non-specific binding. Slides were apposed to X-ray film (β-Max, Amersham) for 3 days in light-tight cassettes, and included with each film was a 14C plastic standard (ARC 146, American Radiolabeled Chemicals) which had been calibrated previously for 125I values for quantitative densitometry.1,29

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase immunocytochemistry

Sections were immunoreacted using standard immunohistochemistry techniques. Briefly, slides were warmed to room temperature, and wells were created around the sections using melted petroleum jelly. Sections were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, preincubated in 10% normal horse serum to block non-specific staining for 1 hr, followed by an overnight incubation with a monoclonal dopamine-β-hydroxylase antibody (1:1000; Chemicon International). Sections then were incubated with horse, anti-mouse, preabsorbed secondary antibody (Vector Labs) for 1 hr, and the product was visualized using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Labs) with the glucose oxidase/nickel ammonium sulfate/diaminobenzidine enhancement method of Shu et al.22

Confirmation of lesion

To determine the effectiveness of the lesion, coded DBH-immunoreacted sections were examined with a microscope (Nikon Optiphot II) and a qualitative comparison of ipsilateral and contralateral bulbs was made. The density of remaining DBH-positive fibers within the two bulbs was compared by eye, and the bulb with the greater number of fibers was recorded.

Quantitative autoradiography

Autoradiographs and DBH-immunoreacted slides were coded separately to eliminate observer bias. The density of β-adrenergic receptors (BARs) was quantified across bulb sections using a computerized image analysis system (Image, NIH; M1, MCID). Optical density values were converted to 125I values (dpm/mm2) using calibration curves calculated from the optical density readings from the plastic standards and the known 125I calibrated values.1,29,30 The outer edge of the glomerular layer was outlined and receptor densities were measured from the bulb sections excluding the olfactory nerve layer. Five sections per brain were analysed approximately 1180-2200 μm from the rostral pole, and the inter-section distance was 200 μm. Ipsilateral and contralateral bulbs were measured separately and compared using a paired t-test.

Beta-2-receptor autoradiographs were subjected to additional image analysis to quantify high-density glomerular β-2 foci (Image, NIH). Calibrated levels of binding were assigned colors that were matched across brains, and images were printed in color (Epson). All printouts were coded, and β-2 glomerular foci were demarcated on the printouts. A focus was defined as a high-density region in the glomerular layer in which boundaries could be distinguished from adjacent regions, and at least a portion of the focus had to reach a minimum density value (approximately 50 dpm/mm2). Beta-2 glomerular foci in both ipsilateral and contralateral bulbs were counted on the printed copies in 11-15 sections per brain, approximately 1040-2800 μm from the rostral pole.

RESULTS

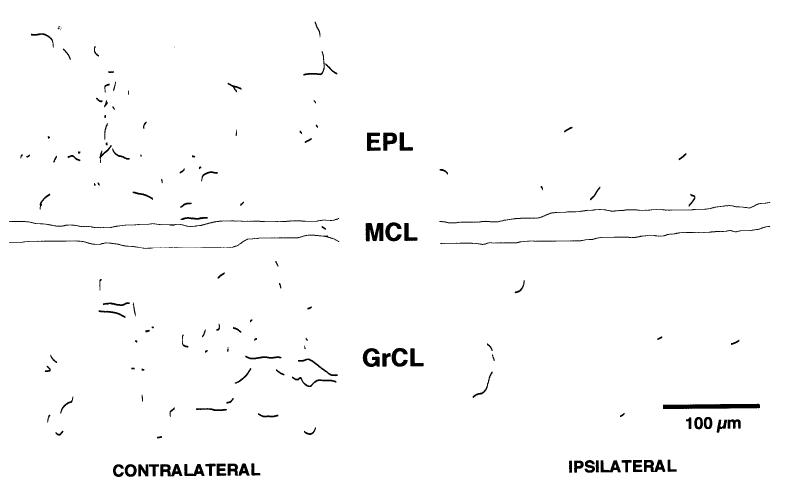

The DBH-positive fibers in the olfactory bulb contralateral to the locus coeruleus lesion were prevalent in the granule cell layer, with some fibers extending through the external plexiform layer, occasionally reaching the glomerular layer (Fig. 1). In the ipsilateral bulb, DBH-positive fibers were extremely sparse with sporadic immunopositive fibers visible in the granule cell layer (Fig. 1). The density of remaining DBH-positive fibers varied across brains, and it appeared that, in some animals, a partial bilateral lesion had occurred. Therefore, only five animals, in which a qualitative difference in DBH-positive fibers could be detected between the two bulbs, were included in the study. The other two animals were discarded. Of the five animals included, one animal was lesioned on the right and the other four animals were lesioned on the left. One of the four left-lesioned animals had no infusate injected in the contralateral locus coeruleus, while the other three left-lesioned animals had vehicle injected in the contralateral locus coeruleus. There was no apparent difference in the density of remaining DBH-positive fibers in the bulbs of vehicle-injected and non-injected animals.

Fig. 1.

Camera lucida drawing of dopamine-β-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in a 20 μm coronal section of the main olfactory bulb. The locus coeruleus was lesioned on the right-hand side in this animal on postnatal day 4, resulting in the paucity of immunopositive fibers ipsilateral to the locus coeruleus lesion on postnatal day 19. The mitral cell layer has been delineated with solid lines.

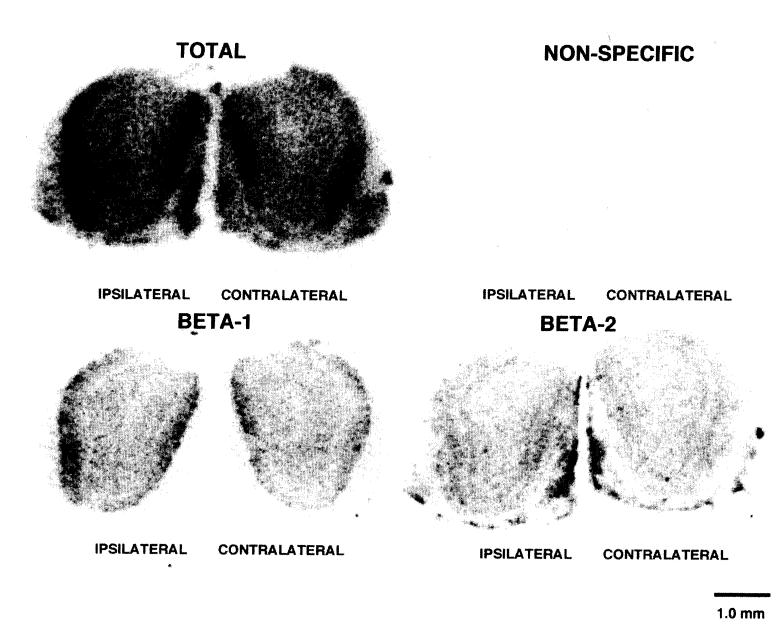

To determine whether changes in locus coeruleus projections to the bulbs affected the β-adrenergic receptor population, total β-adrenergic receptor binding was compared between ipsilateral and contralateral bulbs. Qualitatively, the laminar distribution of the β-adrenergic receptors did not change remarkably, although the density of receptors within the laminas appeared to increase in the ipsilateral bulb compared to the contralateral bulb (Fig. 2). Quantitative measures of the total β-adrenergic receptor density across the entire bulb revealed a statistically significant increase in BAR density in the ipsilateral bulb compared to the contralateral bulb (paired t = 4.27, two-tailed P = 0.013). Both β-1- and β-2-receptor subtypes were affected by the loss of noradrenergic input. Paired comparisons between ipsilateral and contralateral bulbs showed a statistically significant difference between bulbs for β-1-receptors (paired t = 2.845, one-tailed P = 0.023). In addition, although not apparent without image analysis, similar differences were observed between bulbs for β-2-receptors (paired t = 2.307, one-tailed P = 0.041).

Fig. 2.

Computer-enhanced images of 125I-iodopindolol binding to β-adrenergic receptors in the main olfactory bulb of a postnatal day 19 rat ipsilateral and contralateral to an early unilateral locus coeruleus lesion. An increased density of β-adrenergic receptors is present in the bulb ipsilateral to the locus coeruleus lesion compared to the contralateral bulb. Panels illustrate total, non-specific (isoproterenol), β-1 (ICI 118,551)- and B-2 (ICI 89,406)-receptor binding in 20 μm coronal bulb sections.

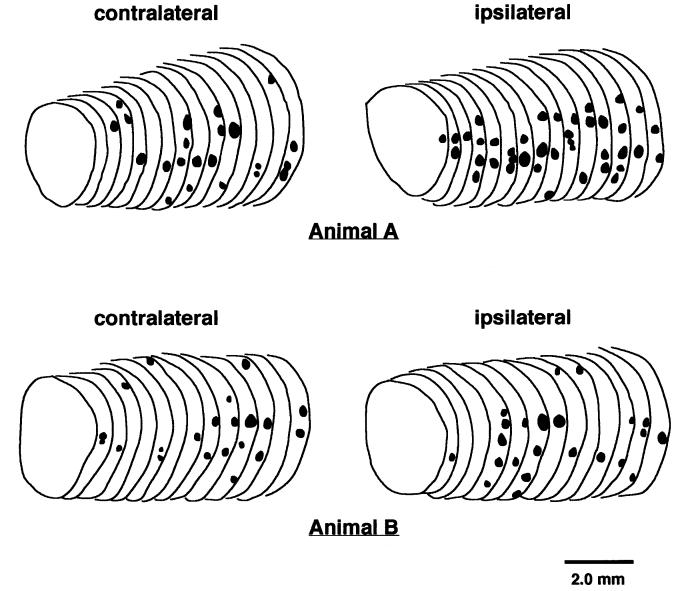

Although the number of β-2 glomerular foci was greater in the ipsilateral bulb compared to the contralateral bulb in four of the five animals, this difference did not reach statistical significance (paired t = 1.9, one-tailed P = 0.065). While some animals had a large difference in the number of β-2 glomerular foci between the bulbs, others had a small difference (Fig. 3). The distribution of the foci did not appear to differ greatly between bulbs or animals, with the majority of the foci being located in the mid- and ventro-lateral portions of the glomerular layer.

Fig. 3.

Tracings of semi-serial coronal olfactory bulb sections illustrating the variability in the distribution of high-density glomerular β-2 foci following early unilateral locus coeruleus lesion. In animal (A), a large increase in the number of β-2 foci was observed in the ipsilateral compared to the contralateral bulb. In contrast, in animal (B), a small difference in the number of β-2 foci was observed between the bulbs ipsilateral and contralateral to the locus coeruleus lesion.

DISCUSSION

Bilateral 6-OHDA lesions of the locus coeruleus on PND 4 lead to a significant reduction of norepinephrine in the main olfactory bulb on PND 7 and disrupt early olfactory learning.26 Similarly produced unilateral lesions on PND 4 also result in a large reduction of DBH-positive fibers in the ipsilateral olfactory bulb when examined on PND 19. Thus, it is likely that norepinephrine levels in the ipsilateral bulb remain diminished 2 weeks post-lesion. This reduction in the density of locus coeruleus afferents to the olfactory bulb is associated with a significant increase in the density of β-adrenergic receptors in the bulb, an effect similar to that found in other brain regions following a locus coeruleus lesion.2,8,11 It remains a possibility, however, that locus coeruleus lesions could result in an increased receptor density through mechanisms other than by changing bulb norepinephrine levels.

Regulation of the β-1- and β-2-receptor subtypes appears to vary in different brain regions, and differential regulation of the two receptor subtypes can be observed in certain brain regions following locus coeruleus lesions.11 Since the density of both β-1- and β-2-adrenergic receptor subtypes increased in the ipsilateral bulb compared to the contralateral bulb, it appears that these two β-adrenergic receptor subtypes can be regulated similarly in the olfactory bulb.

Although β-1- and β-2-adrenergic receptor densities increased in the ipsilateral bulb relative to the contralateral bulb, the number of β-2 glomerular foci was not significantly different between the two bulbs with a unilateral locus coeruleus lesion. It is possible, then, that the number of high receptor density β-2 foci in the glomerular layer is regulated differentially compared to the β-2-receptors in other laminae of the bulb. Since locus coeruleus lesions were performed on PND 4, the norepinephrine present from PND 1-3 could have influenced the development of the β-2-receptor foci. It is also possible that the higher receptor density in the glomerular layer obscured the delineation of the β-2 foci, perhaps reducing the estimate of the number of these foci in the ipsilateral bulb.

The increased density of β-adrenergic receptors in the ipsilateral bulb provides evidence that the majority of β-adrenergic receptors in the bulbs are not pre-synaptic autoreceptors on the locus coeruleus afferents as has been observed in the peripheral nervous system.14 Our findings here are in agreement with in situ hybridization studies, which have shown a bulbar location for β-adrenergic receptor mRNA.9,18 It remains a possibility, however, that a subset of β-adrenergic receptors are autoreceptors on the locus coeruleus afferents.

In conclusion, the increased density of β-adrenergic receptors in the bulb following a locus coeruleus lesion is consistent with the notion that these receptors can be regulated by bulb norepinephrine levels. Thus, it is likely that the early olfactory experiences that change bulb norepinephrine levels can affect the density of β-adrenergic receptors in the bulb.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Chris Lemon for technical assistance with the locus coeruleus lesions, and Dr Brett Johnson for reviewing the manuscript. This research was funded by NICHD HD24236 to M. L. and NIH DC00489 to R. M. S.

Abbreviations

- PND

postnatal day

- DBH

dopamine-β-hydroxylase

- BAR

β-adrenergic receptor

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

REFERENCES

- 1.Baskin DG, Wimpy H. Calibration of [14C] plastic standards for quantitative autoradiography of [125I] labeled ligands with Amersham Hyperfilm β-max. Neurosci. Lett. 1989;104:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battisti WP, Artymyshyn RP, Murray M. β1- and β2-adrenergic 125I-pindolol binding sites in the interpeduncular nucleus of the rat: normal distribution and the effects of deafferentation. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:2509–2518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02509.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beer M, Hacker S, Poat J, Stahl SM. Independent regulation of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;92:827–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunjes PC, Smith-Crafts LK, McCarthy R. Unilateral odor deprivation: effects of the development of olfactory bulb catecholamines and behavior. Dev. Brain Res. 1985;22:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erdtsieck-Ernste EBHW, Feenstra MGP, Botterblom MHA, Boer GJ. Developmental changes in rat brain monoamine metabolism and β-adrenoceptor subtypes after chronic prenatal exposure to propranolol. Neurochem. Intl. 1993;22:589–598. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(93)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambarana C, Ordway GA, Hauptmann M, Tejani-Butt S, Frazer A. Central administration of 1-isoproterenol in vivo induces a preferential regulation of β2-adrenoceptors in the central nervous system of the rat. Brain Res. 1991;555:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harden TK, Wolfe BB, Sporn JR, Poulos BK, Molinoff PB. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine on the development of the beta adrenergic receptor/adenylate cyclase system in rat cerebral cortex. J. Pharm. Expl Ther. 1977;203:132–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harik SI, Duckrow RB, LaManna JC, Rosenthal M, Sharma VK, Banerjee SP. Cerebral compensation for chronic noradrenergic denervation induced by locus coeruleus lesion: recovery of receptor binding, isoproterenol-induced adenylate cyclase activity, and oxidative metabolism. J. Neurosci. 1981;1:641–649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-06-00641.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivins KJ, Ibrahim E, Leon M. Localization of β-adrenergic receptor RNA in the olfactory bulb of neonatal rats. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1993;19:124. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffe EH, Cuello AC. The distribution of catecholamines, glutamate decarboxylase and choline acetyltransferase in layers of the rat olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 1980;186:232–237. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson EW, Wolfe BB, Molinoff PB. Regulation of subtypes of β-adrenergic receptors in rat brain following treatment with 6-hydroxydopamine. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:2297–2305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02297.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones LS, Gauger LL, Davis JN. Anatomy of brain α1-adrenergic receptors: in vitro autoradiography with [125I]-heat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;231:190–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce JN, Lenow N, Kim SJ, Artymyshyn R, Senzon S, Lawrence D, Cassanova MF, Kleinman JE, Bird ED, Winokur A. Distribution of β-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human post-mortem brain: alterations in limbic regions of schizophrenics. Synapse. 1992;10:228–246. doi: 10.1002/syn.890100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langer SZ. Presynaptic regulation of the release of catecholamines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1981;32:337–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLean JH, Shipley MT. Postnatal development of the noradrenergic projection from locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991;304:467–477. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLean JH, Shipley MT, Nickell WT, Aston-Jones G. Chemoanatomical organization of the noradrenergic input from locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb of the adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;285:330–349. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nadi NS, Hirsch JD, Margolis FL. Laminar distribution of putative neurotransmitter amino acids and ligand binding sites in the dog olfactory bulb. J. Neurochem. 1980;34:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb04632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholas AP, Pieribone V, Hokfelt T. Cellular localization of messenger RNA for β-1- and β-2-adrenergic receptors in rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience. 1993;56:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palacios JM, Kuhar MJ. Beta adrenergic receptor localization in rat brain by light microscopic autoradiography. Neurochem. Intl. 1982;4:473–490. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(82)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rainbow TC, Parsons B, Wolfe BB. Quantitative autoradiography of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors in rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:1585–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rangel S, Leon M. Early odor preference training increases olfactory bulb norepinephrine. Dev. Brain Res. 1995;85:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00211-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu S, Ju G, Fan L. The glucose oxidase-DAB-nickel method in peroxidase histochemistry of the nervous system. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;85:169–171. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan RM, McGaugh JL, Leon M. Norepinephrine-induced plasticity and one-trial olfactory learning in neonatal rats. Dev. Brain Res. 1991;60:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90050-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan RM, Wilson DA. The role of norepinephrine in the expression of learned olfactory neurobehavioral responses in infant rats. Psychobiology. 1991;19:308–312. doi: 10.3758/bf03332084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan RM, Wilson DA, Leon M. Norepinephrine and learning-induced plasticity in infant rat olfactory system. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:3998–4006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03998.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan RM, Wilson DA, Lemon C, Gerhardt GA. Bilateral 6-OHDA lesions of the locus coeruleus impair associative olfactory learning in newborn rats. Brain Res. 1994;643:306–309. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan RM, Zyzak DR, Skierkowski P, Wilson DA. The role of olfactory bulb norepinephrine in early olfactory learning. Dev. Brain Res. 1992;70:279–282. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90207-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson DA, Wood JG. Functional consequences of unilateral olfactory deprivation: time course and age sensitivity. Neuroscience. 1992;49:183–192. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90086-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo CC, Leon M. Distribution and development of β-adrenergic receptors in the rat olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;352:1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo CC, Leon M. Early olfactory enrichment and deprivation both decrease β-adrenergic receptor density in the main olfactory bulb of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;360:634–642. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]