Abstract

Background

Reconstruction of giant midline abdominal wall hernias is difficult, and no data are available to decide which technique should be used. It was the aim of this study to compare the “components separation technique” (CST) versus prosthetic repair with e-PTFE patch (PR).

Method

Patients with giant midline abdominal wall hernias were randomized for CST or PR. Patients underwent operation following standard procedures. Postoperative morbidity was scored on a standard form, and patients were followed for 36 months after operation for recurrent hernia.

Results

Between November 1999 and June 2001, 39 patients were randomized for the study, 19 for CST and 18 for PR. Two patients were excluded perioperatively because of gross contamination of the operative field. No differences were found between the groups at baseline with respect to demographic details, co-morbidity, and size of the defect. There was no in-hospital mortality. Wound complications were found in 10 of 19 patients after CST and 13 of 18 patients after PR. Seroma was found more frequently after PR. In 7 of 18 patients after PR, the prosthesis had to be removed as a consequence of early or late infection. Reherniation occurred in 10 patients after CST and in 4 patients after PR.

Conclusions

Repair of abdominal wall hernias with the component separation technique compares favorably with prosthetic repair. Although the reherniation rate after CST is relatively high, the consequences of wound healing disturbances in the presence of e-PTFE patch are far-reaching, often resulting in loss of the prosthesis.

Reconstruction of giant midline abdominal wall hernias that cannot be closed primarily is a technical challenge to a surgeon. Many surgeons discourage abdominal wall reconstruction because of the technical difficulties, the high morbidity, and the relatively high recurrence rate associated with these procedures. However, many patients with large hernias have invalidating complaints such as bulging of the abdominal wall, chronic wounds, immobility, and back pain, necessitating surgical treatment.

The lack of sufficient tissue requires the insertion of prosthetic material or transposition of autologous material to bridge the fascial gap. Reconstruction using pre-peritoneally placed prosthetic material is still the most frequently applied method of reconstruction.1 The increased risk of infection in case of wound complications is a relative contraindication against the use of prosthetic materials. Moreover, interposition of either peritoneum or greater omentum between the bowel and the prosthesis is often impossible, which is another reason to avoid the use of prosthetic material.

In 1990 Ramirez, Ruas, and Dellon introduced the “components separation technique (CST)” to bridge the fascial gap without the use of prosthetic material.2 The technique is based on enlargement of the abdominal wall surface by separation and advancement of the muscular layers. In this way, defects of up to 20 cm at the waistline can be bridged. Retrospective series report promising results, but no prospective study has been published until now.3–12 It was the aim of this prospective study to compare the results of prosthetic repair with CST in patients with giant abdominal wall hernias that cannot be closed primarily. The primary endpoint of the study was reherniation; secondary endpoints were operation time and postoperative wound complications. In the present report the results of an interim analysis are presented.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Adult patients (18–80 years) with an incisional hernia after midline laparotomy with a craniocaudal length of at least 20 cm that could not be closed primarily, in whom the repair could be performed under clean or clean-contaminated conditions, and who were not using corticosteroid therapy were asked to participate in the study. Patients with perioperative gross contamination of the operative field were excluded from the study. After written informed consent the patients were randomized between CST and prosthetic repair by the data center of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre using envelope, the day before operation.

Fully trained abdominal wall surgeons who had done at least five procedures of both techniques before the start of the study performed the operations. H.v.G. and R.P.B. performed supervision in centers not having this expertise. Before each procedure, a preoperative chest x-ray was made. Demographic data, co-morbidity (COPD, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes), body mass index, condition of the skin, size of the hernia at the time of the operative procedure, kind of anesthesia, operation time, perioperative blood loss, postoperative ICU stay, analgesia use, complications, hospital stay, and follow-up were recorded on a standard form. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics commissions of all the participating hospitals. All patients gave written informed consent after receiving a thorough explanation of the study.

Operative Technique

Standard thrombosis (Nadroparine 2,850 IE) and antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazoline 3 × 1 g and metronidazole 3 × 500 mg) were started preoperatively. After induction of anesthesia (combined general and epidural, if possible) and disinfection of the skin with iodine tincture, an adhesive drape was applied on the skin, if possible. The abdomen was entered via a midline laparotomy or at the lateral edge of the graft if the bowels were covered with a split skin graft. Adhesions between the ventral abdominal wall and the intra-abdominal viscera were cut, after which the length and width of the defect were measured.

Components Separation Technique (CST Group)

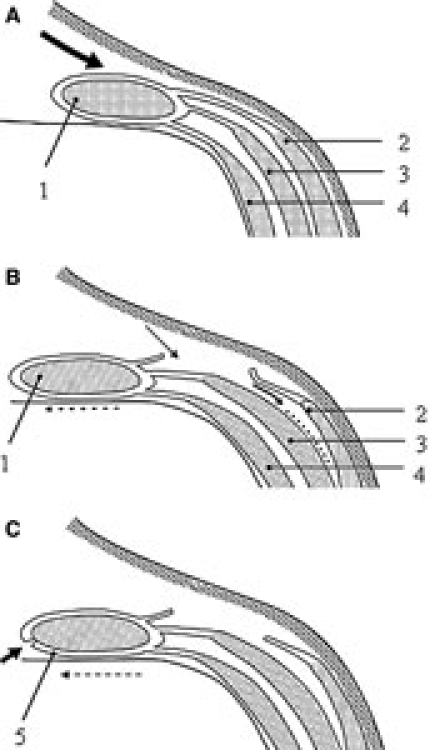

The component separation technique was performed as described in detail in former publications.2,12,13 Briefly, the skin and subcutaneous fat are dissected free from the anterior rectus sheath and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle (Figure 1A). The aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is transected longitudinally about 2 cm lateral from the rectus sheath, including the muscular part that inserts on the thoracic wall, which extends at least 5–7 cm cranially of the costal margin (Figure 1B). The external oblique muscle is separated from the internal oblique muscle as far laterally as possible (Figure 1B). The posterior rectal sheath is separated from the rectus abdominis muscle if tension-free closure is impossible (Figure 1C). The fascia is closed in the midline with a running polydioxanone suture (PDS-loop, Johnson & Johnson, Ltd.) of at least 4 times the length of the incision. The skin is closed over at least two closed suction drains.

Figure 1.

Operative technique of the “components separation technique.” 1 = rectus abdominis muscle; 2 = external oblique muscle; 3 = internal oblique muscle; 4 = transversus abdominis muscle; 5 = posterior rectal sheath. A. Dissection of skin and subcutaneous fat. B. Transaction of aponeurosis of external oblique muscle and separation of internal oblique muscle. C. Mobilization of posterior rectal sheath and closure in the midline. Adapted from Bleichrodt et al.13, with permission of Elsevier.

Prosthetic Repair (e-PTFE Group)

The skin and subcutaneous tissue are mobilized from the underlying fascia of the rectus abdominis muscle. As a consequence all epigastric perforating arteries supplying the overlying skin are separated. After adhesiolysis , a 20 × 30 cm, 1.5-mm-thick e-PTFE patch (Gore-Tex dual mesh plus with holes, W. L. Gore and associates Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) is shaped in size and implanted intra-abdominally as underlay with an overlap of at least 4 cm to the aponeurosis, as described elsewhere.14 The mesh is placed intra-abdominally as an underlay and is sutured under slight tension to the ventral abdominal wall using a double row of interrupted sutures of e-PTFE 1/0 (Gore-Tex 1/0, W. L. Gore and associates Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) that passed the rectus abdominis muscle. The prosthesis is implanted with the microporous side facing the intra-abdominal viscera and the macroporous side facing the fascia. (As a consequence of the large size of the hernias, the fascia could not be closed over the prosthesis in any of the patients in our series.) After implantation, the skin is closed over at least two closed suction drains.

Postoperative Care

Antibiotic prophylaxis, cefazoline 3 × 1 g and metronidazole 3 × 500 mg was started preoperatively and continued for the first 24 h postoperatively. All patients have epidural anesthesia if possible. Wounds were inspected on a daily basis with respect to hematoma, seroma, skin necrosis, and wound infection. Hematoma was defined as an accumulation of blood in the operative field for which a surgical intervention (puncture or drainage) was needed; seroma as an accumulation of fluid in the operative field for which an intervention (puncture or drainage) was needed in case of mechanical or physical limitations. Skin edge necrosis was defined as necrotic loss of full thickness skin for which surgical intervention was needed.

The wound was scored on a daily basis according to CDC criteria, as follows15: grade 1: normal wound, grade 2: erythema and swelling, grade 3: purulent effluent; or grade 4: open wound. Drains were removed after 5 days or if production was less than 50 ml/24 h.

The thorax was examined daily by physical examination, and a routine x-ray of the thorax was performed on the second and seventh days after the operation, to detect pneumonia and atelectasis. No specific instructions were given to the patients after operation and patients had no restriction of physical activity except heavy lifting. Follow-up was done in the outpatient clinic at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after operation. At each visit a physical examination was done to diagnose recurrent hernia. Ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) scanning was performed on indication, especially to detect small recurrences.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were analyzed as per intention to treat. Hernia recurrence-free survival was compared using the Kaplan-Meier methods according to the intention-to-treat principle.

Power Analysis

Type I and II errors were set to 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. The minimum relevant difference in reherniation between groups was set to 30%, in advantage of CST. Accordingly, a minimum of 84 patients was required (two groups of 42 patients). An interim analysis was planned to evaluate the results of the trial after inclusion of 40 patients.

Differences between groups were analyzed using the Fisher exact test for demographic data, preoperative and perioperative data, wound complications, reoperation, and reherniation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristic of patients with prosthetic repair or components separation technique

| Group 1: prosthetic repair | Group 2: components separation technique | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (t-test) | |||

| Age (mean) | 58.7 (range: 42–82) | 53.9 (range: 33–37) | NS |

| (Fisher exact test) | |||

| Gender (women/men) | 6/12 | 6/13 | NS |

| (t-test) | |||

| BMI | 28.7 (range: 21.5–39.6) | 28.2 (range: 23.9–38.7) | NS |

| Defect (median) (cm) | (t-test) | ||

| Length | 25 (range: 20–30) | 25 (range: 20–33) | NS |

| Width | 17 (range: 9–30) | 15 (range: 7–25) | NS |

| Skin (n) | (t-test) | ||

| Intact, full thickness | 14 | 12 | NS |

| Intact, split skin | 4 | 7 | NS |

| Anesthesia (n) | (Fisher exact test) | ||

| General | 3 | 5 | NS |

| Epidural and general | 15 | 14 | NS |

| (t-test) | |||

| Operative time (min) | 183 (range 135–254) | 113 (range 63–175) | p < 0.001 |

| (t-test) | |||

| Blood loss (ml) | 420 (range 100–900) | 289 (range 50–1000) | NS |

| ICU stay | (Mann-Whitney U-test) | ||

| Patients (n) | 6 | 3 | NS |

| Time (days) | 2 (range: 1–6) | 5 (range: 1–10) | NS |

| (t-test) | |||

| Pulmonary complications (n) | 2 | 4 | NS |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 1 | NS |

| Atelectasis | 0 | 3 | NS |

| Analgesia | (t-test) | ||

| Epidural (days) | 2.4 (range: 0–5) | 2.4 (range: 0–6) | NS |

| Morphine (days) | 3.3 (range: 0–8) | 3.6 (range: 0–10) | NS |

| (Fisher exact test) | |||

| Wound complication (n) | 1 | 1 | NS |

| Hematoma | 7 | 4 | NS |

| Seroma | 3 | 2 | NS |

| Skin necrosis | 2 | 3 | NS |

| Infected mesh (n) | 7 | 0 | |

| (t-test) | |||

| Reoperation (in OR) for wound complications (n) | 7 | 2 | p = 0.05 |

| Recurrence (n) | 11 | 10 | NS |

BMI: body mass index; ICU: intensive care unit; NS: not statistically significant; OR: Operation room.

RESULTS

Between November 1999 and June 2001, 39 patients were included in the study and were operated on by one of 5 surgeons. Two patients were excluded from the study because of gross contamination during operation. Nineteen patients, 6 women and 13 men, were randomized to the CST group: reconstruction using the components separation technique. The mean age of these 19 patients was 53.9 years (range: 33–73 years). Eighteen patients, 6 women and 12 men, were randomized to the e-PTFE group (prosthetic repair). Their mean age was 58.7 years (range: 42–82 years).

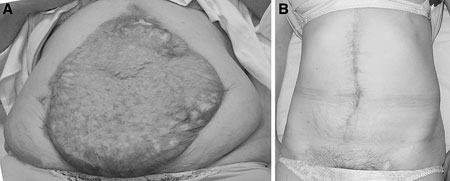

In the CST group, closure of the fascia was accomplished in 18 of the 19 patients (Figure 2). In one patient the abdominal wall hernia was too large and had to be repaired using a combination of the CST and prosthetic repair. In the e-PTFE group the procedure was successful in 17 of the 18 patients. In one patient the abdominal wall hernia was too large and was reconstructed using a combination of prosthetic repair and CST. No differences were found between the groups with respect to demographic data (Table 1), co-morbidity, length and width of the defect, skin coverage, anesthesia, blood loss, and ICU stay (Table 1). All operations were performed without major intraoperative complications, except for the two excluded patients with gross perioperative contamination. The operation time for prosthetic repair was significantly longer as compared with the components separation technique (p < 0.001, Fisher exact test) (Table 1). This is mainly due to the time-consuming fixation of the patch to the fascia with a double row of single sutures.

Figure 2.

A. Preoperative view of a giant abdominal wall hernia covered with a split skin. B. Postoperative view of the same abdominal wall after reconstruction using the components separation technique.

Postoperative Mortality and Morbidity

There was no 30-day mortality. Major wound complications were found in 10 of the 19 patients in the CST group: wound infection (n = 3), skin necrosis (n = 2), hematoma (n = 1). Four patients developed seroma; these were not associated with the aforementioned complications.

Major wound complications were found in 13 of the 18 patients in the e-PTFE group: wound infection (n = 2), skin necrosis (n = 3), hematoma (n = 1). Both wound infection and skin necrosis ultimately resulted in loss of the prosthesis (Table 1). Seven patients developed a seroma. In two of these patients seroma puncture was performed to prevent spontaneous evacuation via the midline wound; this resulted in infection and, ultimately, loss of the patch. Seven patches were removed after a median period of 94 days (range: 30–262 days). In the cases where the prosthesis was removed, the abdominal wall defect was reconstructed using CST.

Pulmonary complications were found in 4 patients in the CST group and 2 in the e-PTFE group (not significant, Fisher exact test) (Table 1).

Reherniation

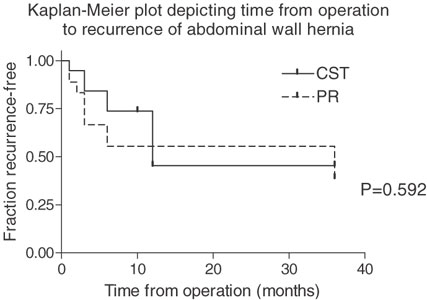

Follow-up was complete in all patients. Four patients in the CST group died before the end of the follow-up period 5, 9, 10, and 12 months after the operation from unrelated causes. Two had a reherniation at the time of death. Of the remaining 15 patients, 8 had a reherniation. Recurrences occurred after a mean period of 7 months (range: 0.5–12 months). Recurrences were all located in the midline in the upper abdomen and were small. Two patients underwent reconstruction of their recurrence. One patient in whom the reconstruction was performed with a combination of CST and prosthetic bridging had a recurrent hernia at the edge of the prosthesis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier for recurrent hernia after prosthetic repair (n = 18) and components separation technique (n = 19). Seven of 18 prostheses were removed during the first 7 months after implantation. Reherniation rates after 36 months are similar in both groups.

Prosthetic Repair

One patient in the e-PTFE group died 6 months after the operation from an unrelated cause. Of the remaining 17 patients, 7 had an infected prosthesis that had to be removed. The abdominal wall defect was then reconstructed using CST repair. Four other patients had a small recurrent hernia after prosthetic repair, without complaints. Recurrences occurred after a mean period of 22 months (range: 6–36 months). None of these four patients underwent reoperation for their recurrence (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first randomized controlled trial comparing different techniques to repair giant midline hernias and the first prospective trial regarding the “component separation technique.” Although our series is relatively small, the results suggest that repair of giant abdominal wall defects with the component separation technique compares favourably with prosthetic repair, because wound infection in patients in whom a prosthetic repair was performed had major consequences, resulting in removal of the prosthesis in 7, whereas wound infection in patients after CST had only minor consequences.

Disturbed wound healing frequently complicates repair of large abdominal wall hernias. Wound complications such as hematoma, seroma, skin necrosis, and infection are reported in 12%–67% of patients after CST2–5,7–12,16 and in 12%–27% after prosthetic repair. Wound complications are associated with the extensive dissection needed in both procedures, which are often performed after intra-abdominal catastrophes. The risk is further increased by the long duration of the operative procedure and the need to mobilize the skin in dividing the epigastric perforating arteries (Figure 4). This endangers the blood supply of the skin, because then it solely depends on the intercostal arteries, which may have been damaged during former operations by introduction of drains, or by stoma construction and other procedures needed in patients with intra-abdominal sepsis.17–19 Wound complications in our series were rather frequent. Although they are mentioned in most other publications about CST, the method of follow-up is mentioned in only one other study from our own group.12

Figure 4.

The operation wound after performing a components separation technique for abdominal wall reconstruction, showing the large wound surface and the extensive skin dissection needed.

Loss of the prosthesis may also be associated with the choice of the prosthetic material used. Several materials have been developed for hernia repair. In the present series only patients with giant and often complex hernias were included. In the majority of these patients the peritoneum or greater omentum was not available to interpose between the prosthesis and the intra-abdominal viscera. Therefore, an e-PTFE dual patch was used to bridge the fascial gap. The expanded-PTFE dual patch has significantly better mechanical properties than polypropylene-mesh. It is a soft pliable microporous material that causes no mechanical trauma to the viscera. The micropores on both sides of the patch are too small to allow ingrowth of fibrocollagenous tissue, thus preventing fibrous adhesions on the visceral side of the patch. Lack of ingrowth results in insufficient anchorage of the patch to the adjacent fascia, however, and this is a major disadvantage of e-PTFE patches.14,20,21 The patch should be placed as underlay with an overlap of at least 4 cm and fixed to the aponeurosis with a double row of single sutures.14

The e-PTFE patch is prone to infection because of its hydrophobic characteristics. To reduce the infection risk, the e-PTFE patch used is impregnated with silver salts and chlorhexidine, which both have anti-microbial properties and work synergistically.22 Moreover, antibiotic prophylaxis was given to all patients and an adhesive drape was applied to the skin. Nevertheless, 40% of our patients had an early or late infection resulting in removal of the patch. In a recent experimental study in rats with a large abdominal wall defect, it was found that impregnation with silver salts resulted in an aggravated inflammatory response around the patch and an increased reherniation rate.23 This observation may explain the increased risk for seroma formation, which is associated with prosthetic loss in this study. Some patients (n = 3, 16%) were operated under clean-contaminated condition, which means they had an accidental bowel lesion during adhesiolysis without gross contamination. We suspect that most surgeons still place a prosthetic patch for abdominal wall reconstruction in these situations, which is supported by some small series in the literature.24,25

In our opinion polypropylene, which is still the most widely used material for hernia repair, is contraindicated because of its propensity for inducing extensive visceral adhesions and occasional fistula formation.26–28 If large areas of polypropylene mesh are exposed, scar contraction will result in wrinkling of the polypropylene mesh, causing mechanical irritation, which promotes infection and carries the risk of mesh erosion into the skin or the intestine.29 If the polypropylene mesh cannot be covered with full-thickness skin, chronic infection and sinus formation will ultimately result in loss of the mesh.27 Therefore the results probably would not have been better if polypropylene mesh or polypropylene mesh based prosthesis was used.

Recurrent hernia still is a major problem The only randomized controlled trial comparing open suture and mesh repair of small ventral hernias was reported by Luijendijk et al. reporting recurrence rates of 46% and 23%, respectively, after a follow-up of 36 months and 63% and 32%, respectively, after a follow-up of 75 months.1,30 In retrospective studies recurrence rates of 25%–63% in suture repair and 8%–25% in mesh repair are reported. Tension-free repair of incisional hernia is a prerequisite to prevent recurrence. In CST a tension-free repair was accomplished. In the literature recurrence rates of 0%–28% have been reported for CST, although how follow-up was accomplished is not well documented in most series.2–12 But it seems impossible to have a reherniation rate, in series of large abdominal wall defects, that is far below the reherniation rate of reconstruction of small abdominal wall defects in a well performed randomized controlled trial.1,30

Despite the high recurrence rate in the present study and our retrospective study, CST remains an attractive technique for repair of giant ventral hernias. Most recurrent hernias are small and asymptomatic and need no further treatment. In addition, the functional and cosmetic results are good and patients were satisfied.

In a recent other study in 39 patients undergoing CST repair for heavily contaminated abdominal wall defects, similar results were found with respect to complications and reherniation rate (36%).31 All but one patient indicated satisfaction with the result when compared to their situation before operation. In that study, postoperative quality of life was assessed using the SF 36 questionnaire. When compared to the general population, patients had an average score or higher on pain, vitality, social functioning, and role limitations (emotional problems); the score was below average on physical functioning, role limitations (physical problems), in general health perception, and in mental health.31

On the basis of the interim analysis, the trial was discontinued because the frequency of wound complications resulting in subsequent prosthetic loss was unacceptably high. Because underlay repair necessitates transection of the perforating epigastric arteries in patient with prosthetic repair it was expected that this complication could not be prevented, whereas CST remains possible if the epigastric perforators are spared. Impregnation of the e-PTFE patch with silver salts and chlorhexidine might have contributed to this.23 Recently, a prospective randomized controlled trial has started comparing CST with CST + preperitoneal polypropylene mesh support, combining the advantages of CST and prosthetic repair.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Frima and D. de Jong for their participation in the study.

References

- 1.Luijendijk RW, Hop WJC, van den Tol MP, et al. A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med 2000;343:392–398 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ramirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL. “Components separation” method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990;86:519–526 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.DiBello JN Jr, Moore JH Jr. Sliding myofascial flap of the rectus abdominus muscles for the closure of recurrent ventral hernias. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;98:464–469 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Girotto JA, KoMj, Redett R, et al. Closure of chronic abdominal wall defects: a long-term evaluation of the components separation method. Ann Plast Surg 1999;42:385–394 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cohen M, Morales R Jr, Fildes J, et al. Staged reconstruction after gunshot wounds to the abdomen. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hobar PC, Rohrich RJ, Byrd HS. Abdominal-wall reconstruction with expanded musculofascial tissue in a posttraumatic defect. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994;94:379–383 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Jernigan TW, Fabian TC, Croce MA, et al. Staged management of giant abdominal wall defects: acute and long-term results. Ann Surg 2003;238:349–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Kuzbari R, Worseg AP, Tairych G, et al. Sliding door technique for the repair of midline incisional hernias. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101:1235–1242 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lowe JB III, Lowe JB, Baty JD, et al. Risks associated with “components separation” for closure of complex abdominal wall defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111:1276–1283 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Shestak KC, Edington HJ, Johnson RR. The separation of anatomic components technique for the reconstruction of massive midline abdominal wall defects: anatomy, surgical technique, applications, and limitations revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:731–738 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Sukkar SM, Dumanian GA, Szczerba SM, et al. Challenging abdominal wall defects. Am J Surg 2001;181:115–121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.de Vries Reilingh TS, van Goor H, Rosman C, et al. “Components separation technique” for the repair of large abdominal wall hernias. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:32–37 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bleichrodt RP, de Vries Reilingh TS, Maylar A, et al. Component separation technique to repair large midline hernias. Operative Tech Gen Surg 2004;6:179–188 [DOI]

- 14.van der Lei B, Bleichrodt RP, Simmermacher RK, et al. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene patch for the repair of large abdominal wall defects. Br J Surg 1989;76:803–805 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Am J Infect Control 27:97–132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ennis LS, Young JS, Gampper TJ, et al. The “open-book” variation of component separation for repair of massive midline abdominal wall hernia. Am Surg 2003;69:733–742 [PubMed]

- 17.Taylor GI, Corlett RJ, Boyd JB. The versatile deep inferior epigastric (inferior rectus abdominis) flap. Br J Plast Surg 1984;37:330–350 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Maas SM, de Vries Reilingh TS, van Goor H, et al. Endoscopically assisted “components separation technique” for the repair of complicated ventral hernias. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:388–390 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Maas SM, van Engeland M, Leeksma NG, et al. A modification of the “components separation” technique for closure of abdominal wall defects in the presence of an enterostomy. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189:138–140 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Simmermacher RK, van der Lei B, Schakenraad JM, et al. Improved tissue ingrowth and anchorage of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene by perforation: an experimental study in the rat. Biomaterials 1991;12:22–24 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Simmermacher RK, Schakenraad JM, Bleichrodt RP. Reherniation after repair of the abdominal wall with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene. J Am Coll Surg 1994;178:613–616 [PubMed]

- 22.Quesnel LB, Al Najjar AR, Buddhavudhikrai P. Synergism between chlorhexidine and sulphadiazine. J Appl Bacteriol 1978;45:397–405 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.de Vries Reilingh TS et al. Impregnation of E-PTFE abdominal wall patches with silver salts and chlorohexidine diminishes biocompatibility and is associated with an increased reherniation rate. Submitted

- 24.Kelly ME, Behrman SW. The safety and efficacy of prosthetic hernia repair in clean-contaminated and contaminated wounds. Am Surg 2002;68:524–528 [PubMed]

- 25.Stringer RA, Salameh JR. Mesh herniorrhaphy during elective colorectal surgery. Hernia 2005;9:26–28 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Basoglu M, Yildirgan MI, Yilmaz I, et al. Late complications of incisional hernias following prosthetic mesh repair. Acta Chir Belg 2004;104:425–428 [PubMed]

- 27.Lucas CE, Ledgerwood AM. Autologous closure of giant abdominal wall defects. Am Surg 1998;64:607–610 [PubMed]

- 28.de Vries Reilingh TS, Geldere D, Langenhorst B, et al. Repair of large midline incisional hernias with polypropylene mesh: comparison of three operative techniques. Hernia 2004;8:56–59 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kaufman Z, Engelberg M, Zager M. Fecal fistula: a late complication of Marlex mesh repair. Dis Colon Rectum 1981;24:543–544 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Burger JW, Luijendiyk RW, Hop WC, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg 2004;240:578–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bodegom ME et al. Component separation technique for contaminated abdominal wall defects. Submitted