Abstract

We have identified sultam thioureas as novel inhibitors of West Nile virus (WNV) replication. One such compound inhibited WNV, with a 50% effective concentration of 0.7 μM, and reduced reporter expression from cells that harbored a WNV-based replicon. Our results demonstrate that sultam thioureas can block a postentry, preassembly step of WNV replication.

West Nile virus (WNV) and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) are members of the Flavivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family of viruses (9, 13). These viruses are considered emerging human pathogens (11, 12, 19, 29, 32, 37). They are closely related to the yellow fever and dengue flaviviruses, and together, these four pathogens are responsible for a significant percentage of virally induced human encephalitis cases worldwide (10-12, 19, 29, 32, 37). One line of defense against flaviviruses is the formulation of vaccines, usually directed against the viral surface envelope (E) proteins (12, 37). Another possible option is the intravenous administration of antiviral antibodies (25, 35). A complementary approach has been the development of small-molecule flavivirus inhibitors (7, 9, 15, 17, 20, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 38, 39).

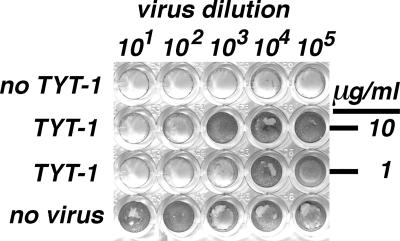

To assay for novel WNV inhibitors, we screened a diverse library of approximately 3,500 members for compounds that protected Vero cells from WNV-induced cytopathic effects (CPE). Cells were exposed continuously to a compound concentration of 10 μg/ml (10 to 50 μM) along with a 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) carrier, infected with WNV (NY 1999) (19, 24) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2, and monitored for CPE at 3 to 5 days postinfection (p.i.). Of the candidate WNV inhibitors identified, the sultam thiourea TYT-1 (Fig. 1) appeared the most potent in replicate screens. TYT-1's anti-WNV effects were confirmed in virus yield reduction assays (19, 29). Mock-treated and TYT-1-treated Vero cells were infected for 24 h, after which virus-containing medium samples were titrated by limiting dilution on fresh cells in the absence of new compound. An example of our results is shown in Fig. 2. As illustrated and expected, medium from mock-treated, mock-infected (“no virus”) cells yielded no deleterious effects on new cells. In contrast, dilutions of ≥105 from mock-treated infected (“no TYT-1”) cells generated virus sufficient to lyse new cell monolayers completely. However, treatment of cells with 2.3 or 23 μM TYT-1 reduced 24-h virus yields ≥100-fold (Fig. 2), substantiating the initial screen results.

FIG. 1.

Compound structures. The diagrams show the structures of the following sultams: TYT-1, N′-(1,1-dioxido-2-phenyl-1,4,2-dithiazolidin-3- ylidene)-N,N-diphenylthiourea (439.6 kDa); TYT-2, (2,5-dimethyl-1,1-dioxido-1,4,2-dithiazolidin-3-ylidene)bis(1-methylethyl)thiourea (323.5 kDa); TYT-3, [1,1-dioxido-2-(phenylmethyl)-1,4,2-dithiazolidin-3-ylidene]bis(1- methylethyl)-thiourea (385.6 kDa); and TYT-4, (1,1-dioxido-2-phenyl-1,4,2-dithiazolidin-3-ylidene)-bis(phenylmethyl)-thiourea (467.6 kDa).

FIG. 2.

WNV yield reduction. Vero cells in medium containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin were mock treated with DMSO (no TYT-1; no virus; final DMSO concentration, 1%) or treated with the indicated concentration of TYT-1 in DMSO and then mock infected (no virus) or infected with WNV at an MOI of 1.0. At 24 h p.i., virus-containing medium samples at the indicated dilutions were used to infect fresh cells. At 5 days p.i., surviving cells were stained with 0.0375% crystal violet. Infected, mock-treated wells were devoid of cells due to WNV-mediated cell killing, and wells were routinely scored as virus positive if cell staining levels were reduced three-fourths or more relative to uninfected cell staining levels. Note that 2.3 and 23 μM TYT-1 reduced WNV titers at least 100-fold and that these results are representative of more than 10 independent experiments.

Determination of the TYT-1 concentration needed to reduce WNV titers twofold (50% effective concentration [EC50]) followed the virus yield reduction regimen described above. As illustrated in Fig. 3 (black bars), the EC50 of TYT-1 against WNV was approximately 0.7 μM. Since our original screening protocol scored for protection of cells from virus-induced CPE, it appeared that TYT-1 was not toxic to cells, at least at 23 μM. However, to test this directly, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of TYT-1 and assayed after 48 h for dehydrogenase levels in metabolically active cells, using MTS {3-[(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium]} substrate (6). At the highest concentration tested (70 μM), TYT-1 did not reduce viability signals to the 50% level (Table 1). This result was confirmed microscopically by trypan blue (0.2%) exclusion (data not shown), indicating a 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) for TYT-1 of >70 μM. Thus, the net therapeutic or selectivity index (CC50/EC50) for TYT-1 against WNV in Vero cells is >100.

FIG. 3.

Effective anti-WNV drug concentrations. Increasing concentrations of TYT-1 (black bars), TYT-2 (striped bars), TYT-3 (gray bars), and TYT-4 (white bars) were used to determine effective anti-WNV concentrations by virus yield reduction assays. Results are plotted as concentrations versus percentages of virus yields observed in mock-treated (1% DMSO [final concentration]) controls. Titers were determined by limiting dilution and scored as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Averages (means) were derived from three separate experiments for TYT-1 and at least two separate experiments for TYT-2 to -4, and standard deviations are shown.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of sultam thiourea compounds

Compound EC50 values for WNV were derived from the virus yield reduction results shown in Fig. 2, while EC50 values for JEV were obtained in a similar fashion from two to four independent experiments.

The CC50 values were determined by MTS cytotoxicity assays performed in quadruplicate. Note that 50% cytotoxicity was defined as a 50% drop in background-subtracted MTS signals and that for TYT-1 and TYT-3, 50% cytotoxicity was not obtained with the highest drug concentrations employed.

Although TYT-1 showed antiviral effects against WNV, at 23 μM it did not inhibit adenovirus 5, the Prospect Hill (2) hantavirus, or a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) expression vector (data not shown). However, in virus yield reduction tests with JEV (SA14-2-8) (30), TYT-1 again inhibited virus replication, albeit with an EC50 of 7 μM, which is 10-fold higher than its EC50 against WNV (Table 1). Because very few analogues of TYT-1 have been described (28), our ability to probe structure-activity relationships is currently limited. However, we have examined the cytotoxic and antiflavivirus effects of three available TYT-1 analogues, TYT-2, TYT-3, and TYT-4 (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1, none of these showed impressive antiviral effects against WNV, with EC50 values of >20 μM. Moreover, TYT-2 and TYT-4 appeared to be cytotoxic at 50 to 100 μM (Table 1). However, TYT-3 was not cytotoxic at the highest concentration tested and gave some level of protection against JEV (Table 1).

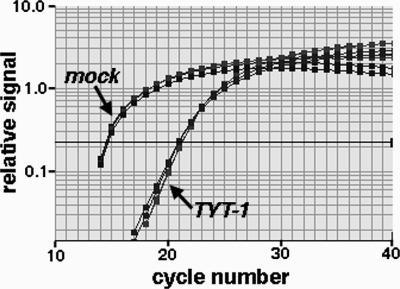

To ascertain how TYT-1 might inhibit WNV, we initially probed viral protein levels in treated and untreated acutely infected cells. Vero cells that were mock treated or treated with TYT-1 were infected with WNV and processed for either immunofluorescence (4, 18) or immunoblot (18, 23) detection of the viral E protein. Importantly, regardless of the detection method employed, we found that TYT-1 treatment dramatically reduced E protein levels in infected cells (data not shown). We also addressed whether WNV RNA levels are reduced by TYT-1 treatment through quantitation of RNA levels by real-time PCR (8, 19). With mock-treated, mock-infected, negative control Vero cells, no WNV RNA signals were observed (data not shown). With mock-treated, infected, positive control cells, real-time PCR signals were halfway through their exponential increase phase by cycle number 15 (Fig. 4), corresponding to 3,255 ± 325.8 WNV RNA copies per cell, as quantitated relative to an in vitro-transcribed NS3 RNA standard. Treatment of infected cells with TYT-1 clearly shifted the amplification signals to higher cycle numbers (Fig. 4), corresponding to 27.2 ± 1.6 WNV RNA copies per cell. Thus, TYT-1-mediated inhibition of WNV E expression was accompanied by a >100-fold reduction in WNV RNA levels.

FIG. 4.

WNV RNA levels in treated and untreated cells. Vero cells were mock treated with DMSO (“mock”; final concentration, 0.5% DMSO) or treated with 11 μM TYT-1 in DMSO (“TYT-1”) and then mock infected (not shown) or infected with WNV at an MOI of 5. At 18 h p.i., RNAs were isolated, and equivalent input RNA amounts were reverse transcribed and subjected to real-time PCR quantitation of WNV RNA levels following previously described protocols (8, 19). The results, plotted as relative fluorescence signals versus PCR cycle numbers, indicate the following average (n = 4) WNV RNA copy numbers per cell, as quantitated relative to an in vitro-transcribed NS3 RNA standard: for uninfected cells, 0; for untreated cells, 3,255 ± 325.8; and for TYT-1-treated cells, 27.2 ± 1.6. Reverse transcription-PCR cycle parameters were 30 min at 48°C for the reverse transcription step, 10 min at 95°C for a denaturation step, and 40 cycles of 13 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C.

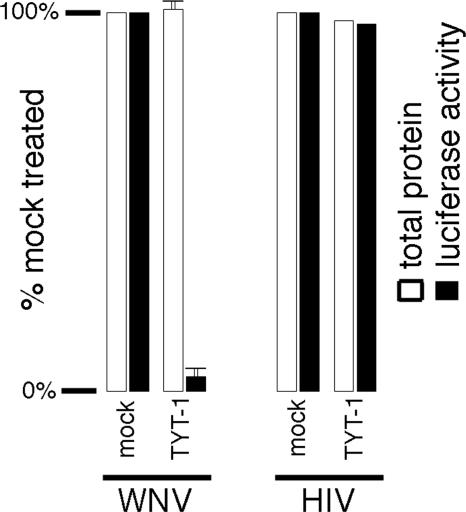

The observed reductions of WNV protein and RNA levels imply that TYT-1 exerts its antiviral activity prior to the assembly stage of virus replication. However, these experiments did not discriminate whether inhibition occurs at viral entry or postentry steps. One way to distinguish between these possibilities is to screen for antiviral activity when an inhibitor is added after the onset of infection. When such time course experiments were undertaken, using a virus yield reduction readout, we found that TYT-1 application as late as 2 h p.i. gave similar levels of virus inhibition to those obtained when cells were pretreated with the drug (data not shown). Additionally, we tested TYT-1 effects on baby hamster kidney (BHK) 26.5 cells (33), which stably harbor a WNV replicon expressing a luciferase reporter gene. To do so, BHK or BHK 26.5 cells were mock treated for 48 h with DMSO (0.1% final concentration) or with 23 μM TYT-1 (final concentration) in DMSO and processed for determination of luciferase activities (34) and total protein levels (Bio-Rad). Significantly, TYT-1 treatment of these WNV replicon-expressing cells reduced luciferase reporter levels >20-fold but did not alter cellular total protein levels (Fig. 5, left panel). In contrast, TYT-1 did not reduce luciferase levels in control cells expressing the protein from an HIV-1-based (34) vector (Fig. 5, right panel).

FIG. 5.

WNV replicon inhibition. BHK cells expressing a WNV luciferase replicon (WNV) (33) or 293 cells transfected with an HIV-based luciferase expression vector (HIV) (34) were mock treated with DMSO (0.1% [final concentration]) or treated with 23 μM TYT-1 in DMSO. At 48 h posttreatment, cells were processed for detection of total protein levels (white bars) or luciferase activities (black bars). Protein levels and luciferase levels are expressed as percentages of the values obtained for mock-treated samples; background luciferase levels with parental BHK and untransfected 293 cells were <0.1% of the 100% values shown. Values obtained for WNV replicon samples were averaged from four separate experiments and are shown with standard deviations.

The above results demonstrate that TYT-1 blocks a postentry, preassembly step of WNV replication. However, the precise mechanism by which TYT-1 exerts its antiviral effects is not known. Since the compound reduced virus levels in African green monkey Vero cells and viral replicon levels in BHK 26.5 cells, its effects are not specific to one cell type or species. Another observation which suggests that our sultam thioureas interfere with a virus-specific target is that TYT-1 and TYT-3 showed opposite differential effects on WNV versus JEV (Table 1); it is difficult to reconcile how these results might occur if the two compounds were to act on a common cellular factor. Thus, the accumulated data (Table 1; Fig. 2 to 5) suggest that TYT-1 targets a sensitive step somewhere in the middle of the virus replication cycle. Conceivably, inhibition could occur via a block to viral translation, polyprotein processing, or RNA replication, but further investigation will be needed to dissect the mechanism in greater detail and to determine whether the potency of TYT-1 will be sufficient for therapeutic purposes in vivo.

We could find no reports concerning the potential biological activities of sultam thioureas closely related to TYT1-4. However, numerous sulfonamides have been employed as inhibitors of a diverse set of proteases (1). Moreover, several sultams have been considered excellent antiarthritic drug candidates by virtue of their activities against matrix metalloproteinases (1, 14, 21, 22, 31). While these reports might point to the WNV protease as the TYT-1 target, sultams have been reported to block other enzyme activities. For instance, sultam derivatives have been shown to inhibit histone deacetylase (3), HIV reverse transcriptase (5), and HIV integrase (16) activities. Thus, available data on sultam activities do not help to implicate a particular TYT-1 target. Indeed, given the limited number of available TYT-1 analogues (Fig. 1), it is important to emphasize that even the requirement of a sultam ring for TYT-1 or TYT-3 antiflavivirus activity is uncertain. The results suggest that replacement of the TYT-1 thiourea nitrogen phenyl groups with isopropyl (TYT-3) or methylphenyl (TYT-4) substituents has a significant impact on antiviral activity (Table 1), but considerably more study will be needed to determine how and how well these inhibitors act as antivirals.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Peter Mason, who provided BHK and BHK 26.5 cells, along with advice concerning their use. We also appreciate the efforts of Kathy Shinall for secretarial support, of Travis Rogers for tissue culture support, and of Robin Lid Barklis for organizational support.

Our investigations were funded by a grant from the NIH (R21 AI56248) to E.B., by NIH contract support (1 50027) to J.N.-Z., and by NIH training grant support (5 T32 AI007472-12) to A.A and J.B.

OHSU and E.B. have filed a patent application on the use of the described compounds and derivatives as antivirals and thus have a commercial interest in these investigations.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbenante, G., and D. Fairlie. 2005. Protease inhibitors in the clinic. Med. Chem. 171-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfadhli, A., Z. Love, B. Arvidson, J. Seeds, J. Willey, and E. Barklis. 2001. Hantavirus nucleocapsid protein oligomerization. J. Virol. 752019-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 2003. Tricyclic lactam and sultam derivatives as histone deacetylase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 13387-391. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvidson, B., J. Seeds, M. Webb, L. Finlay, and E. Barklis. 2003. Analysis of the retrovirus capsid interdomain linker region. Virology 308166-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, D. C., and B. Jiang. March 2002. Sultams: solid phase and other synthesis of anti-HIV compounds and compositions. U.S. patent 6,353,112 B1.

- 6.Barltrop, J., T. Owen, A. Cory, and J. Cory. 1991. 5-(3carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-3-(4-sulfophenyl)tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) and related analogs of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (mTT) reducing to purple water-soluble formazans as cell-viability indicators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1611. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borowski, P., M. Lang, A. Haag, H. Schmitz, J. Choe, H.-M. Chen, and R. Hosmane. 2002. Characterization of imidazo(4,5-d)pyridazine nucleosides as modulators of unwinding reaction mediated by West Nile virus nucleoside triphosphatase/helicase: evidence for activity on the level of substrate and/or enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 461231-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briese, T., W. Glass, and W. I. Lipkin. 2000. Detection of West Nile virus sequences in cerebrospinal fluid. Lancet 3551614-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinton, M. 2002. The molecular biology of West Nile virus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56371-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Outbreak of West Nile-like viral encephalitis—New York. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 4825-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Provisional surveillance summary of the West Nile virus epidemic—United States, January-November 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 511129-1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005. West Nile virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/index.html.

- 13.Chambers, T., C. Hahn, R. Galler, and C. Rice. 1990. Flavivirus genome organization, expression, and replication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44649-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherney, R., R. Mo, D. Meyer, K. Hardman, R. Liu, M. Covington, M. Qian, Z. Wasserman, D. Christ, J. Trzaskos, R. Newton, and C. Decicco. 2004. Sultam hydroxamates as novel matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 472981-2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courageot, M.-P., M.-P. Frenkiel, C. Duarte Dos Santos, V. Deubel, and P. Despres. 2000. α-Glucosidase inhibitors reduce dengue virus production by affecting the initial steps of virion morphogenesis in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 74564-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dayam, R., J. Deng, and N. Neamati. 2006. HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: 2003-2004 update. Med. Res. Rev. 26271-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamond, M., M. Zachariah, and E. Harris. 2002. Mycophenolic acid inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing replication of viral RNA. Virology 304211-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen, M., L. Jelinek, S. Whiting, and E. Barklis. 1990. Transport and assembly of Gag proteins into Moloney murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 645306-5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch, A., G. Medigeshi, H. Meyers, V. DeFilippis, K. Fruh, T. Briese, W. I. Lipkin, and J. Nelson. 2005. The Src family kinase c-Yes is required for maturation of West Nile virus particles. J. Virol. 7911943-11951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong, Z., and C. Cameron. 2002. Pleiotropic mechanisms of ribavirin antiviral activities. Prog. Drug Res. 5941-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagaki, M. 2003. Studies on the new antiarthritic drug candidate S-2474. Yakugaku Zasshi 123323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inagaki, M., T. Tsuri, H. Jyoyama, T. Ono, K. Yamada, M. Kobayashi, Y. Hori, A. Arimura, K. Yasui, K. Ohno, S. Kakudo, K. Koizumi, R. Suzuki, S. Kawai, M. Kato, and S. Matsumoto. 2000. Novel antiarthritic agents with 1,2-isothiazolidine-1,1-dioxide (gamma-sultam) skeleton: cytokine suppressive dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase. J. Med. Chem. 432040-2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones, T. A., G. Blaug, M. Hansen, and E. Barklis. 1990. Assembly of Gag-β-galactosidase proteins into retrovirus particles. J. Virol. 642265-2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordan, I., T. Briese, N. Fischer, J. Lau, and W. I. Lipkin. 2000. Ribavirin inhibits West Nile virus replication and cytopathic effect in neural cells. J. Infect. Dis. 1821214-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura-Kuroda, J., and K. Yasui. 1988. Protection of mice against Japanese encephalitis virus by passive administration with monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. 1413606-3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung, D., K. Schroder, H. White, N.-X. Fang, M. Stoermer, G. Abbenante, J. Martin, P. Young, and D. Fairlie. 2001. Activity of recombinant dengue 2 virus NS3 protease in the presence of a truncated NS2B cofactor, small peptide substrates, and inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 27645762-45771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leyssen, P., J. Balzarini, E. De Clercq, and J. Neyts. 2005. The predominant mechanism by which ribavirin exerts its antiviral activity in vitro against flaviviruses and paramyxoviruses is mediated by inhibition of IMP dehydrogenase. J. Virol. 791943-1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linden, H., and J. Goerdeler. 1977. Ring opening cycloadditions. 5. Reaction of iminodithiazoles with sulfenes in 5-membered sultams. Tetrahedron Lett. 201729-1732. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrey, J., D. Smee, R. Sidwell, and C. Tseng. 2002. Identification of active antiviral compounds against a New York isolate of the West Nile virus. Antivir. Res. 55107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni, H., N. Burns, G. Chang, M. Zhang, M. Wills, D. Trent, P. Sanders, and A. Barrett. 1994. Comparison of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of the 5′ non-coding region and structural protein genes of the wild-type Japanese encephalitis virus strain SA14 and its attenuated vaccine derivatives. J. Gen. Virol. 751505-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page, M. 2004. Beta-sultams—mechanism of reactions and use as inhibitors of serine proteases. Acc. Chem. Res. 37297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puig-Basagoiti, F., M. Tilgner, B. Forshey, S. Philpott, N. Espina, D. Wentworth, S. Goebel, P. Masters, B. Falgout, P. Ren, D. Ferguson, and P.-Y. Shi. 2006. Triaryl pyrazoline compound inhibits flavivirus RNA replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 501320-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi, S., Q. Zhao, V. O'Donnell, and P. Mason. 2005. Adaptation of West Nile virus replicons to cells in culture and use of replicon-bearing cells to probe antiviral action. Virology 331457-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholz, I., B. Arvidson, D. Huseby, and E. Barklis. 2005. Virus particle core defects caused by mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus capsid N-terminal domain. J. Virol. 791470-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimoni, Z., M. Niven, S. Pitlick, and S. Bulvik. 2001. Treatment of West Nile virus encephalitis with intravenous immunoglobulin. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitby, K., T. Pierson, B. Geiss, K. Lane, M. Engel, Y. Zhou, R. Doms, and M. Diamond. 2005. Castanospermine, a potent inhibitor of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 798698-8706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. 2002. Immunization vaccines and biologicals: Japanese encephalitis. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/vaccines-disease/diseases/je.shtml.

- 38.Wu, S.-F., C.-J. Lee, C.-L. Liao, R. Dwek, N. Zitzmann, and Y.-L. Lin. 2002. Antiviral effects of an iminosugar derivative on flavivirus infections. J. Virol. 763596-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, N., H. Chen, V. Koch, H. Schmitz, M. Minczuk, P. Stepien, A. Fattom, R. Naso, K. Kalicharran, P. Borowski, and R. Hosmane. 2003. Potent inhibition of NTPase/helicase of the West Nile virus by ring-expanded (“fat”) nucleoside analogues. J. Med. Chem. 464776-4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]