Abstract

We report on the first occurrence of high-level gentamicin resistance (MICs ≥ 512 μg/ml) in seven clinical isolates of Streptococcus pasteurianus from Hong Kong. These seven isolates were confirmed to be the species S. pasteurianus on the basis of nucleotide sequencing of the superoxide dismutase (sodA) gene. Epidemiological data as well as the results of pulse-field gel electrophoresis analysis suggested that the seven S. pasteurianus isolates did not belong to the same clone. Molecular characterization showed that they carried a chromosomal, transposon-borne resistance gene [aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia] which was known to encode a bifunctional aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme. The genetic arrangement of this transposon was similar to that of Tn4001, a transposon previously recovered from Staphylococcus aureus and other gram-positive isolates. Genetic linkage with other resistance elements, such as the ermB gene for erythromycin resistance, was not evident. On the basis of these findings, we suggest that routine screening for high-level gentamicin resistance should be recommended for all clinically significant blood culture isolates. This is to avoid the inadvertent use of short-course combination therapy with penicillin and gentamicin, which may lead to the failure of treatment for endocarditis, the selection of drug-resistant Streptococcus pasteurianus and other gram-positive organisms, as well as the unnecessary usage of gentamicin, a drug with potential toxicity.

Streptococcus bovis is an important cause of bacteremia and endocarditis (21, 22, 26, 27, 31, 33). The association between S. bovis bacteremia and malignancy of the colon is well recognized, exceeding 50% in some studies (2, 21, 22, 27, 31). An association between S. bovis bacteremia and chronic liver disease has also been noted (12, 38, 44). Recently, this pathogen has increasingly been recognized as an important cause of infective endocarditis, particularly among the elderly. In a recent survey of infective endocarditis cases in France, S. bovis accounted for 25% of the 390 cases from whom isolates were collected, while viridans group streptococci were responsible for only 17% of the cases (15). S. bovis bacteremia has been associated with higher rates of mortality and cardiac surgery compared with the rates of association for viridans group streptococci (23). The taxonomy of this organism has recently been revised on the basis of DNA homology studies, whole-cell protein analysis, and nucleotide sequencing of the superoxide dismutase (sodA) gene. Streptococcus gallolyticus, Streptococcus infantarius, and Streptococcus pasteurianus have been proposed as replacements for S. bovis biotype I, S. bovis biotype II/1, and S. bovis biotype II/2, respectively (9).

Optimal therapy for streptococcal endocarditis requires a combination of penicillin and an aminoglycoside for a synergistic effect (41, 43). The presence of a high-level aminoglycoside resistance phenotype results in the loss of this synergistic effect both in vitro and in experimental animal models (8, 10, 11). High-level resistance to gentamicin in enterococci and streptococci is usually due to the presence of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene, which encodes a bifunctional aminoglycoside-inactivating enzyme with 6′-acetyltransferase and 2″-phosphotransferase activities. The gentamicin resistance determinant is usually plasmid borne in most strains of Enterococcus faecalis (17, 29) and Enterococcus faecium (42); in addition, it is often found on transposable elements that are structurally related to transposon Tn4001, which was originally recovered from Staphylococcus aureus (25). Chromosomally mediated high-level gentamicin resistance (HLGR) has also been reported in several E. faecalis strains (32, 37), as well as in one group B streptococcus strain (3, 16) and several Streptococcus mitis strains (20).

Although penicillin resistance in S. bovis has not yet been reported, isolates resistant to tetracycline and erythromycin are increasingly recognized (24). As for aminoglycoside resistance, high-level resistance to streptomycin in Streptococcus bovis has been described (6, 18). However, high-level resistance to gentamicin, the aminoglycoside most commonly used for the treatment of endocarditis nowadays, has not been reported. In the literature, gentamicin MICs ranged from 1 to 32 μg/ml in clinical isolates of S. bovis recovered in various clinical settings (10, 30, 36, 40). According to the current CLSI (formerly NCCLS) recommendation, routine screening for HLGR is not necessary for Streptococcus bovis (28). In our laboratory, an isolate of Streptococcus bovis with HLGR was identified in 1995 upon screening with a 120-μg gentamicin disk. Further characterization of this isolate showed that it exhibited a MIC of gentamicin of 4,096 μg/ml. This finding prompted us to undertake the present study to assess the prevalence of organisms with high-level aminoglycoside resistance and to characterize the mechanism of resistance to gentamicin in S. bovis/S. pasteurianus strains isolated from blood cultures over a 12-year period.

(This work was presented in part at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Prague, Czech Republic, May 2004 [V. C. Y. Chow, R. C. Y. Chan, M. L. Chin, and A. F. B. Cheng, Abstr. Eur. Congr. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., abstr. P1467, 2004].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain selection.

A total of 57 nonduplicate isolates of Streptococcus bovis recovered from blood cultures between 1993 and 2005 were studied in the Microbiology Laboratory, Prince of Wales Hospital, a 1,400-bed teaching hospital in Hong Kong. The S. bovis isolates were initially identified to the species level by conventional methods, being differentiated from enterococci and other viridans group streptococci by growth on bile-esculin medium and at 45°C but not in 6.5% NaCl. Their identities were confirmed by using the API 32 Strept system (bioMerieux Inc., Hazelwood, MO), which allowed further delineation of the isolates as biotype I, II/1, or II/2 (5, 34). The identities of seven isolates which were found to exhibit HLGR in subsequent antimicrobial susceptibility tests were further confirmed by nucleotide sequencing of their superoxide dismutase (sodA) genes (9).

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests.

The MICs of 12 antibiotics (penicillin, cefotaxime, vancomycin, tetracycline, erythromycin, clindamycin, gentamicin, streptomycin, kanamycin, amikacin, minocycline, and netilmicin) were determined for all S. bovis/S. pasteurianus isolates by the agar dilution method. A standard disk diffusion test with a 120-μg gentamicin disk (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) was performed for the screening and detection of HLGR among the clinical isolates recovered from blood cultures. Both tests were performed according to the CLSI guidelines (28).

PCR and nucleotide sequencing.

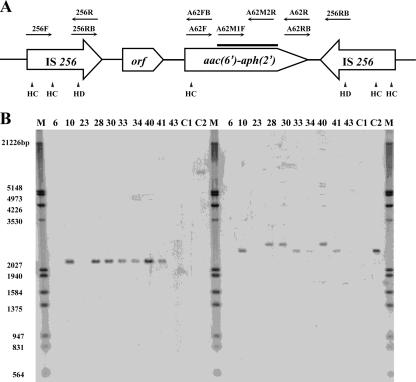

PCR primers were designed to detect the presence of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene and the IS256 insertion elements in both gentamicin-sensitive and -resistant isolates and to determine their relative positions and orientations compared to those in Tn4001. The nucleotide sequences of all primers and their relative positions and orientations within Tn4001 are listed in Table 1 and Fig. 1A, respectively. The isolates were also investigated for the presence of other resistance genes, such as the aph(2″)Ib, -Ic, and -Id genes, which code for various aminoglycoside phosphotransferases, by using the primer sets A2bF/A2bR, A2cF/A2cR, and A2dF/A2dR, respectively (4, 19, 39) (Table 1). Total DNA was extracted from each isolate as described previously (13) and was used as the template in the PCR. A positive control strain, Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 49532), which is highly resistant to gentamicin due to the presence of aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia, was included in the PCR. The gentamicin-sensitive strain Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 was used as the negative control. A primer set was also designed to detect the presence of the ermB gene in the seven HLGR strains (Table 1). A clinical isolate of Streptococcus agalactiae which was known to harbor the ermB gene was used as a control. The identities of all PCR products were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used to detect determinants of gentamicin and erythromycin resistance and analyze their genetic organization in Streptococcus pasteurianus

| Primer name | Nucleotide sequence | PCR product size (bp) | GenBank accession no. of nucleotide sequences used in primer design |

|---|---|---|---|

| 256RB | 5′-GCC GTT CTT ATG GAC CTA CAT-3′ | 625 | M18086 |

| A62FB | 5′-CCA CCA TAA AAT TCT AAT AC-3′ | ||

| A62RB | 5′-GAT ATA TTA AGA ATG TAT GG3-3′ | 368 | M18086 |

| 256RB | 5′-GCC GTT CTT ATG GAC CTA CAT-3′ | ||

| 256F | 5′-TGA AAA GCG AAG AGA TTC AAA GC-3′ | 1102 | M18086 |

| 256R | 5′-ATG TAG GTC CAT AAG AAC GGC-3′ | ||

| A62F | 5′-GTA TTA GAA TTT TAT GGT GG-3′ | 1201 | M18086 |

| A62R | 5′-CCA TAC ATT CTT AAT ATA TC-3′ | ||

| A62M1F | 5′-GCC AGA ACA TGA ATT ACA CGA G-3′ | 469 | M18086 |

| A62M2R | 5′-CTG TAT AAT CTA AAC CGT GCA-3′ | ||

| A2bF | 5′-ATG GTT AAC TTG GAC GCT GAG-3′ | 905 | AF207840 |

| A2bR | 5′-TTC CTG CTA AAA TAT AAA CAT CTC TGC T-3′ | ||

| A2cF | 5′-TGA CTC AGT TCC CAG AT-3′ | 880 | U51479 |

| A2cR | 5′-AGC ACT GTT CGC ACC AAA-3′ | ||

| A2dF | 5′-GAC CAG GTA GAA AAG GCA ATA GAG CAG-3′ | 845 | AF016483 |

| A2dR | 5′-ATA CCA ATC CAT ATA ACC ATA TTC CTT-3′ | ||

| ermBF | 5′-GAA AAA GTA CTC AAC CAA ATA-3′ | 639 | AF242872 |

| ermBR | 5′-AGT AAT GGT ACT TAA ATT GTT TAC-3′ |

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the organization of Tn4001 and the relative positions and orientations of the primers used in this study. The relative positions of the HincII (HC) and the HindIII (HD) sites within Tn4001 are shown. The heavy black line represents the region of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene hybridized with the probe generated by primers A62M1F and A62M2R. (B) Confirmation of the chromosomal location of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia resistance gene by hybridization of HincII (left panel) and HindIII (right panel) chromosomal digests with a probe generated by PCR amplification of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene with primers A62M1F and M2R. ATCC 33317 (lanes C1) and ATCC 49532 (lanes C2) are the gentamicin-sensitive and gentamicin-resistant laboratory reference strains, respectively. Strains SB10, SB28, SB30, SB33, SB34, SB40, and SB41 (lanes 10, 28, 30, 33, 34, 40, and 41, respectively) are HLGR isolates; strains SB6, SB23, and SB43 (lanes 6, 23, and 43, respectively) are gentamicin-sensitive clinical isolates. Lane M, molecular markers (the sizes are as labeled on the left).

PFGE analysis.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed according to the protocol of Duck et al. (7). Genomic DNA from both gentamicin-sensitive and -resistant isolates was fragmented with the endonuclease SmaI or ApaI before electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the pulsed-field banding patterns were analyzed by using Bionumerics software (version 3.0) to delineate the genetic relationships of the test strains.

Southern blotting and DNA hybridization experiments.

Total cellular DNA from each isolate was purified as described previously (13). To determine whether the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene is located in transposon Tn4001, 3 μg of purified DNA was digested with the endonuclease HincII or HindIII, and blotting onto a nylon membrane (Amersham) was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (35). These two enzymes were chosen because each cuts once in such a position within the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene that one digested fragment could be hybridized by the probe. To probe the possible linkage between the gentamicin and erythromycin resistance determinants, a ClaI digest of genomic DNA was used in the hybridization experiments.

The probe used for the detection of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene in the hybridization experiments was the 469-bp PCR product of primers A62M1F and A62M2R, which is an internal fragment of the bifunctional gene. Upon hybridization with the HindIII and HincII digests of genomic DNA, this probe was expected to produce one labeled band of 2.5 kbp and 2.2 kbp, respectively, if the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene is located in a Tn4001-like structure. To probe the genetic arrangement of the IS256 element, a 1,102-bp PCR product that was prepared by PCR amplification with primers 256F and 256R and that covered almost the entire IS256 element was used as the probe. This probe should give three labeled bands per copy of Tn4001 upon hybridization with the genomic digest obtained with the restriction enzyme HindIII, which is known to cut once within each of the two flanking IS256 genes at each end of the transposon (Fig. 1A). This probe was also used to delineate whether the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia genes in the seven HLGR isolates were in fact part of a larger transposon, Tn5384, which also harbored the ermB gene, a determinant for erythromycin resistance. A labeled fragment of approximately 7 kbp in a blot of the HindIII digest would be indicative of the presence of Tn5384 (33). In addition, hybridization of the ClaI digest of chromosomal DNA with the ermB probe, which was prepared by PCR amplification of ermB gene-specific primers (Table 1), would produce a 3.2-kbp fragment if the ermB gene is located in transposon Tn5384 (1). Upon heat denaturation, the probes were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP by random priming (DIG DNA labeling kit; Roche GmbH, Penzberg, Germany). All hybridization experiments were performed by using the DIG nucleic acid detection kit (Roche GmbH). The enzyme substrate nitroblue tetrazolium plus 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate allowed visualization of the labeled DNA banding patterns.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Epidemiological analysis and antibiotic susceptibility tests.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests revealed that all 57 S. bovis isolates tested were sensitive to penicillin. Seven of the 57 (12%) isolates, which were recovered from six patients, were found to exhibit an HLGR phenotype, with MICs ranging from 512 to >4,096 μg/ml. These seven isolates were all found to belong to the species S. pasteurianus, based on their sodA sequences. Nucleotide sequencing of the sodA gene was not performed with the other 50 isolates, to which we continue to refer as S. bovis. Apart from being gentamicin resistant, the seven isolates were also found to be highly resistant to kanamycin and erythromycin. In addition, all isolates except one were also resistant to tetracycline. Table 2 summarizes the susceptibilities of these seven isolates to a total of 10 antibiotics.

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of seven HLGR Streptococcus pasteurianus isolates

| Strain no. | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | Erythromycin | Clindamycin | Tetracycline | Gentamicin | Kanamycin | Streptomycin | Netilmicin | Amikacin | Minocycline | |

| SB10 | 0.06 | >512 | 256 | 128 | >4,096 | >4,096 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 8 |

| SB28 | 0.12 | >512 | 16 | 128 | >4,096 | >4,096 | 64 | 512 | 512 | 16 |

| SB30 | 0.12 | >512 | 0.5 | 128 | >4,096 | >4,096 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 8 |

| SB33 | 0.12 | >512 | 512 | 256 | 2,048 | >4,096 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| SB34 | 0.12 | >512 | 128 | 0.25 | 2,048 | >4,096 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 0.12 |

| SB40 | 0.12 | >512 | 512 | 256 | 1,024 | >4,096 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| SB41 | 0.12 | >512 | 512 | 256 | 512 | >4,096 | 32 | 8 | 32 | 8 |

| EFAEa | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 16 | 32 | 4 | 64 | 1 |

| SBb | 0.06 | 0.06 | <0.03 | 0.25 | 8 | 128 | 64 | 16 | 64 | NDc |

EFAE, Entercoccus faecalis ATCC 29212, used as a drug-susceptible control strain.

SB, Streptococcus bovis ATCC 33317, used as a drug-susceptible control strain.

ND, not determined.

Six of the seven HLGR isolates were recovered in 2001 and 2002. These six isolates represented 44% and 29% of the isolates collected in each of the 2 years respectively; the remaining isolate was recovered in 1995. The six patients from whom the seven HLGR isolates were recovered were all aged over 65 years. Five of the patients had underlying diseases such as diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, or carcinoma. Among the patients, two were diagnosed with acute cholangitis, one was diagnosed with infective endocarditis, and the other three patients were diagnosed with either secondary peritonitis or primary bacteremia. In two of the patients, Escherichia coli and/or Klebsiella spp. were also recovered from their blood cultures. The dates of isolation for each of the seven HLGR isolates also differed from each other.

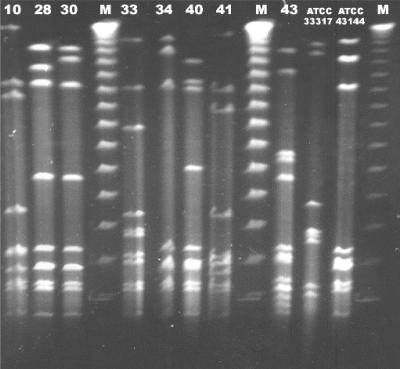

PFGE analysis.

In order to examine whether the seven HLGR isolates were genetically related to each other, we performed PFGE analysis with these isolates, with the results suggesting that they fell into different pulsotype groups. Five of the seven isolates (isolates SB10, SB33, SB34, SB40, and SB41) differed from each other by at least three bands when they were tested with each of the two restriction enzymes used in the study (Fig. 2). The other two isolates (isolates SB28 and SB30), which were recovered from the same patient, who had two episodes of infection separated by a 2-month period, had PFGE patterns that differed from each other by less than three bands in assays with each of the two enzymes used for PFGE; in addition, such patterns were significantly different from those of the other five isolates. The PFGE profiles of the gentamicin-sensitive isolates also revealed a diversity of patterns which also differed significantly from those of the HLGR strains (results not shown). The PFGE results and epidemiological data suggested little clonal relationship among the seven S. pasteurianus isolates.

FIG. 2.

PFGE profiles of genomic DNA digested with SmaI. Lanes 10, 28, 30, 33, 34, 40, and 41, HLGR isolates SB10, SB28, SB30, SB33, SB34, SB40, and SB41, respectively; lane 43, a gentamicin-sensitive clinical S. pasteurianus isolate for which the gentamicin MIC was 8 μg/ml. The profiles of two standard laboratory strains, ATCC 33317 and ATCC 43144, are also included. Lane M, bacteriophage λ PFGE-DNA molecular markers from Amersham Biosciences.

Detection of resistance genes by PCR.

PCR was performed to detect the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene, which was previously implicated as being responsible for HLGR in Staphylococcus and Enterococcus species. A primer pair targeting an internal region of the 1,201 nucleotides of the entire aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene was used for PCR amplification (Table 1). All seven HLGR S. pasteurianus isolates were found to possess the entire resistance gene, as confirmed by nucleotide sequencing of the PCR products. This gene, however, was not detected in any of the gentamicin-sensitive S. bovis isolates. Our PCR results also showed that the seven HLGR isolates did not possess other gentamicin resistance genes, such as aph(2″)Ib, -Ic, and -Id, which have been reported to confer gentamicin resistance in enterococci (4, 19, 39). On the other hand, all seven HLGR S. pasteurianus isolates were also found to harbor the ermB gene, the determinant for erythromycin resistance.

Analysis of genetic arrangement of resistance determinants by PCR and DNA hybridization.

The genetic arrangement of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene and its possible linkage with transposon Tn4001 were examined by further PCR studies with primer pairs targeting two separate regions spanning the IS256 insertion sequence that contained the transposase gene at one end and either the 5′-terminal or the 3′-terminal region of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene at the other end (Fig. 1A). The results of PCR assays and subsequent nucleotide sequencing of the PCR products confirmed that in each of the seven HLGR isolates the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene was inversely flanked by the IS256 gene at both the 5′ and the 3′ ends, in the same manner as previously described for Tn4001 (14). In order to determine the genetic location of this transposon, attempts were made to extract plasmids as well as the chromosomal DNA of the resistant strains, followed by restriction enzyme digestion and hybridization studies, by using the PCR products containing partial sequences of the aac(6′)Ie-aph(2″)Ia gene or IS256 as probes. As plasmids could not be recovered from the seven resistant isolates, hybridization was performed only with restriction enzyme-digested total DNA, with the results confirming the likelihood that the resistance gene resided in the chromosomes of the resistant isolates and that the sizes and the banding patterns of the detected fragment were compatible with those expected for Tn4001.

Figure 1B shows the results of hybridization studies obtained with HincII and HindIII digests of total DNA of the HLGR strains and the A62M1F-A62M2R PCR product as the probe. While only a single-size band was revealed upon hybridization of the HincII digest, there were bands of two different sizes in the HindIII digest. As this phenomenon suggested the possibility that the 5′ end of Tn4001 in these HLGR isolates may exhibit some form of insertional element, we performed further PCR tests using different combination of primers (Table 1) in a crude attempt to map the region of sequence variation in Tn4001. Our results showed that the region between the HindIII site and part of the left-end IS256 fragment of Tn4001, in the vicinity of the 256RB binding site (Fig. 1A) of three HLGR isolates (isolates SB28, SB30, and SB40), was consistently not amplifiable with primers carrying the known IS256 sequences. As these three isolates also exhibited a larger-than-expected fragment upon hybridization of the HindIII digest (Fig. 1B), we hypothesized that such phenomena may be associated with the presence of insertional elements in the left-hand IS256 element of the Tn4001-like transposon of the three isolates mentioned above. Further investigation is required to assess whether such insertion events are associated with a new transposase gene with a possibly altered transposition function.

In addition to the possible genetic variations in the left-hand IS256 element, there were also size differences between the hybridized bands of the S. pasteurianus strains and that of the positive control strain, ATCC 49532, which may also have been due to the presence of insertional elements or sequence variations that led to alteration of the restriction sites and, hence, the sizes of the detected fragments.

Examination of possible genetic linkage of gentamicin and erythromycin resistance determinants in HLGR isolates.

As shown in Table 2, the seven HLGR S. pasteurianus isolates were also highly resistant to erythromycin. This prompted us to investigate whether the Tn4001 found in the HLGR S. pasteurianus isolates was in fact part of a larger transposon, namely, Tn5384, which was first identified in E. faecalis. Bordered by two inverse repeats of the IS256 insertion elements that are 26 kbp apart, this transposon was found to harbor a Tn4001-like element as well as an erythromycin resistance determinant gene (ermB), thereby conferring resistance to both gentamicin and erythromycin in some E. faecalis isolates (33, 1). By using ermB-specific primers in the PCR, all seven HLGR isolates were found to contain the ermB gene (results not shown). Southern blotting and hybridization of ClaI-digested total DNA from the HLGR isolates with a DIG-labeled ermB gene probe revealed the presence of a 2.5-kbp fragment but not the 3.2-kbp ermB-containing fragment, which would have been present in the case of Tn5384 (1). In addition, hybridization of the HindIII digest with the IS256 probe failed to reveal a fragment larger than 7 kbp, which was expected to be present in Tn5384. These results suggest that Tn5384 is not likely to be present in the HLGR isolates; hence, there is not enough evidence to prove that the resistance determinants for gentamicin and erythromycin resistance are genetically linked to each other in the seven S. pasteurianus isolates.

Clinical implications.

This is the first report of HLGR in S. pasteurianus. The cluster of HLGR strains in 2001 and 2002 is interesting. The abrupt appearance of the majority of HLGR strains since 2001 could represent the effect of transfer of genes among strains and evolution. The isolates might have acquired the resistance determinant from different sources, possibly involving members of the food chain, through lateral genetic transfer mechanisms such as conjugation, transformation, or transduction. Although we have no data on the usage of gentamicin in 2001 and 2002, we postulated that an abnormal increase in the usage of gentamicin is one way that these drug-resistant isolates had a better chance of being selected in these 2 years.

HLGR in S. pasteurianus has significant clinical implications, as both the American Heart Association and the British Society of Antimicrobial and Chemotherapy recommend a 2-week course of treatment with penicillin and gentamicin for uncomplicated infective endocarditis caused by penicillin-sensitive strains of viridans group streptococci, including S. pasteurianus (41, 43). According to the recommendations of the CLSI, routine testing for HLGR is not necessary, an omission that makes the recognition of resistance difficult (28). Infections caused by such strains, which are inadvertently treated with a short course of combination therapy with penicillin plus gentamicin, may have high relapse rates. In addition, the unnecessary use of gentamicin, a drug with a narrow therapeutic range that potentially causes nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, is undesirable.

In view of the data presented here, regular surveillance by antibiotic susceptibility testing, including testing for HLGR, in all clinically significant blood culture isolates of S. pasteurianus is warranted. Upon detection of a high prevalence of HLGR, like that which we experienced in our locality during the period of 2001 and 2002, routine screening of S. pasteurianus isolates for HLGR is recommended. Although further studies are needed to explore the potential of high-content gentamicin disk testing for the detection of HLGR in S. pasteurianus, our preliminary data indicate that high-content gentamicin disk testing may offer the laboratory a convenient and reliable test for the rapid screening of this category of resistant organisms.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonafede, M. E., L. L. Carias, and L. B. Rice. 1997. Enterococcal transposon Tn5384: evolution of a composite transposon through cointegration of enterococcal and staphylococcal plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 411854-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns, C. A., M. McCaughey, and C. B. Lauter. 1985. The association of S. bovis fecal carriage and colon neoplasia: a possible relationship with polyps and their premalignant potential. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 8042-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buu-Hoi, A., C. Le Bouguenec, and T. Horaud. 1990. High-level chromosomal gentamicin resistance in Streptococcus agalactiae (group B). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34985-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow, J. W., V. Kak, I. You, S. J. Kao, J. Petrin, D. B. Clewell, S. A. Lerner, G. H. Miller, and K. J. Shaw. 2001. Aminoglycoside resistance genes aph(2″)Ib and aac(6′)Im detected together in strains of both Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 452691-2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coykendall, A. L. 1989. Classification and identification of the viridans streptococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2315-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David, F., G. Cespedes, F. Delbos, and T. Horaud. 1993. Diversity of chromosomal genetic elements and gene identification in antibiotic-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus bovis. Plasmid 29147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duck, W. M., C. D. Steward, S. N. Banerjee, J. E. McGowa, Jr., and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Optimization of computer software setting improves accuracy of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis macrorestriction fragment pattern analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413035-3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enzler, M. J., M. S. Rouse, N. K. Henry, J. E. Geraci, and W. R. Wilson. 1987. In vitro and in vivo studies of streptomycin-resistant, penicillin-susceptible streptococci from patients with infective endocarditis. J. Infect. Dis. 155954-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facklam, R. 2002. What happened to the streptococci?: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15613-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber, B. F., G. M. Eliopoulos, J. I. Ward, K. Ruoff, and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 1983. Resistance to penicillin-streptomycin synergy among clinical isolates of viridans streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 24871-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farber, B. F., and Y. Yee. 1987. High-level aminoglycoside resistance mediated by aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes among viridans streptococci: implications for the therapy for endocarditis. J. Infect. Dis. 155948-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Quintela, A., C. Martinez-Rey, J. F. Castroagudin, M. C. Rajo-Iglesias, and M. J. Dominguez-Santalla. 2001. Prevalence of liver disease in patients with Streptococcus bovis bacteraemia. J. Infect. 42116-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grattard, F., J. Etienne, B. Pozzetto, F. Tardy, O. G. Gaudin, and J. Fleurette. 1993. Characterization of unrelated strains of Staphylococcus schleiferi by using ribosomal DNA fingerprinting, DNA restriction patterns, and plasmid profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31812-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodel-Christian, S. L., and B. E. Murray. 1991. Characterization of the gentamicin resistance transposon Tn5281 from Enterococcus faecalis and comparison to staphylococcal transposons Tn4001 and Tn4031. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 351147-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoen, B., F. Alla, C. Selton-Suty, I. Beguinot, A. Bouvet, S. Briancon, J. P. Casalta, N. Danchin, F. Delahaye, J. Etienne, V. Le Moing, C. Leport, J. L. Mainardi, R. Ruimy, F. Vandenesch, and the Association pour l'Etude et la Prevention de l'Endocarditeinfectieuse (AEPEI) Study Group. 2002. Changing profile of infective endocarditis: results of a 1-year survey in France. JAMA 28875-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horaud, T., G. de Cespedes, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1996. Chromosomal gentamicin resistance transposon Tn3706 in Streptococcus agalactiae B128. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 401085-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horodniceanu, T., L. Bougueleret, N. El-Solh, G. Bieth, and F. Delbos. 1979. High level plasmid-borne resistance to gentamicin in Streptococcus faecalis subsp. zymogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16686-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horodniceanu, T., A. Buu-Hoi, F. Delbos, and G. Bieth. 1982. High-level aminoglycoside resistance in group A, B, G, D (Streptococcus bovis), and viridans streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 21176-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kao, S. J., I. You, D. B. Clewell, S. M. Dorabedian, M. J. Zervos, J. Petrin, K. J. Shaw, and J. W. Chow. 2000. Detection of the high-level aminoglycoside resistance gene aph(2″)-Ib in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 442876-2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufhold, A., and E. Potgieter. 1993. Chromosomally mediated high-level gentamicin resistance in Streptococcus mitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 372740-2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein, R. S., M. T. Catalano, S. C. Edberg, J. L. Casey, and N. H. Steigbigel. 1979. Streptococcus bovis septicemia and carcinoma of the colon. Ann. Intern. Med. 91560-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein, R. S., R. A. Recco, M. T. Catalano, S. C. Edberg, J. I. Casey, and N. H. Steigbigel. 1977. Association of Streptococcus bovis with carcinoma of the colon. N. Engl. J. Med. 297800-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kupferwasser, I., H. Darius, A. M. Muller, S. Mohr-Kahaly, I. Westermeier, H. Oelert, R. Erbel, and J. Meyer. 1998. Clinical and morphological characteristics in Streptococcus bovis endocarditis: a comparison with other causative microorganisms in 177 cases. Heart 80276-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leclercq, R., C. Huet, M. Picherol, P. Trieu-Cuot, and C. Poyart. 2005. Genetic basis of antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus gallolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 491646-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyon, B. R., J. W. May, and R. A. Skuray. 1984. Tn4001: a gentamicin and kanamycin resistance transposon in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 193554-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moellering, R. C., Jr., B. K. Watson, and L. J. Kunz. 1974. Endocarditis due to group D streptococci: comparison of disease caused by Streptococcus bovis with that produced by the enterococci. Am. J. Med. 57239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray, H. W., and R. B. Roberts. 1978. Streptococcus bovis bacteremia and underlying gastrointestinal disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1381097-1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2006. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: sixteenth informational supplement. M100-S16 (M7). National Committee for Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 29.Patterson, J. E., and M. J. Zervos. 1990. High-level gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus: microbiology, genetic basis, and epidemiology. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12644-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renneberg, J., L. L. Niemann, and E. Gutschik. 1997. Antimicrobial susceptibility of 278 streptococcal blood isolates to seven antimicrobial agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynolds, J. G., E. Silva, and W. M. McCornack. 1983. Association of Streptococcus bovis bacteremia with bowel disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 17696-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice, L. B., G. M. Eliopoulos, C. Wennasten, D. Goldmann, G. A. Jacoby, and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 1991. Chromosomally mediated β-lactamase production and gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35272-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rice, L. B., L. L. Carias, and S. H. Marshall. 1995. Tn5384, a composite enterococcal mobile element conferring resistance to erythromycin and gentamicin whose ends are directly repeated copies of IS256. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 391147-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruoff, K. L., R. A. Whiley, and D. Beighton. 1999. Streptococcus, p. 283-296. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and R. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 36.Teng, L. J., P. R. Hsueh, S. W. Ho, and K. T. Luh. 2001. High prevalence of inducible erythromycin resistance among Streptococcus bovis isolates in Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 453362-3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thal, L. A., J. W. Chow, J. E. Patterson, M. B. Perri, S. Donabedian, D. B. Clewell, and M. J. Zervos. 1993. Molecular characterization of highly gentamicin resistant Enterococcus faecalis isolates lacking high-level streptomycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37134-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripodi, M. F., L. E. Adinolfi, E. Ragone, E. Durante Mangoni, R. Fortunato, D. Iarussi, G. Ruggiero, and R. Utili. 2004. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its association with chronic liver disease: an underestimated risk factor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 381394-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai, S. F., M. J. Zervos, D. B. Clewell, S. M. Donabedian, D. F. Sahm, and J. W. Chow. 1998. A new high-level gentamicin resistance gene, aph(2″)-Id, in Enterococcus spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 421229-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanakunakorn, C., and C. Glotzbecker. 1977. Synergism with aminoglycosides of penicillin, ampicillin and vancomycin against non-enterococcal group D streptococci and viridans streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 10133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson, W. R., A. W. Karchmer, A. S. Dajani, K. A. Taubert, A. Bayer, and D. Kaye. 1995. Antibiotic treatment of adults with infective endocarditis due to streptococci, enterococci, staphylococci and HACEK microorganisms. JAMA 2741706-1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woodford, N., E. McNamara, E. Smyth, and R. C. George. 1992. High-level resistance to gentamicin in Enterococcus faecium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1998. Antibiotic treatment of streptococcal, enterococcal, and staphylococcal endocarditis. Heart 79207-210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zarkin, B. A., K. D. Lillemoe, J. L. Cameron, P. N. Effron, T. H. Magnusson, and H. A. Pitt. 1990. The triad of Streptococcus bovis bacteremia, colonic pathology and liver disease. Ann. Surg. 211786-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]