Abstract

The 76-kDa μ1 protein of nonfusogenic mammalian reovirus is a major component of the virion outer capsid, which contains 200 μ1 trimers arranged in an incomplete T=13 lattice. In virions, μ1 is largely covered by a second major outer-capsid protein, σ3, which limits μ1 conformational mobility. In infectious subvirion particles, from which σ3 has been removed, μ1 is broadly exposed on the surface and can be promoted to rearrange into a protease-sensitive and hydrophobic conformer, leading to membrane perforation or penetration. In this study, mutants that resisted loss of infectivity upon heat inactivation (heat-resistant mutants) were selected from infectious subvirion particles of reovirus strains Type 1 Lang and Type 3 Dearing. All of the mutants were found to have mutations in μ1, and the heat-resistance phenotype was mapped to μ1 by both recoating and reassortant genetics. Heat-resistant mutants were also resistant to rearrangement to the protease-sensitive conformer of μ1, suggesting that heat inactivation is associated with μ1 rearrangement, consistent with published results. Rate constants of heat inactivation were determined, and the dependence of inactivation rate on temperature was consistent with the Arrhenius relationship. The Gibbs free energy of activation was calculated with reference to transition-state theory and was found to be correlated with the degree of heat resistance in each of the analyzed mutants. The mutations are located in upper portions of the μ1 trimer, near intersubunit contacts either within or between trimers in the viral outer capsid. We propose that the mutants stabilize the outer capsid by interfering with unwinding of the μ1 trimer.

Introduction

Nonfusogenic mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus) is a nonenveloped icosahedral virus, in which the double-stranded RNA genome is packaged inside a two-layered protein capsid. During infection, reovirus virions are converted to infectious subvirion particles (ISVPs) by proteolytic digestion of the major outer-capsid protein σ3 (Baer and Dermody, 1997; Bodkin et al., 1989; Chang and Zweerink, 1971; Silverstein et al., 1970; Sturzenbecker et al., 1987). Generation of ISVPs can be recapitulated in vitro by digestion with various proteases (Borsa et al., 1973; Ebert et al., 2002; Golden et al., 2004; Joklik, 1972; Nibert and Fields, 1992;), and the resulting particles have (for most reovirus strains (Chappell et al., 1998; Nibert et al., 1995)) a similar infectivity to virions. ISVPs have the membrane-penetration protein μ1 broadly exposed on their surface (Dryden et al., 1993; Liemann et al., 2002; Zhang et al. 2005) and can be promoted in vitro to undergo further irreversible changes in the outer capsid to yield the penetration-associated particle, the ISVP* (Chandran et al., 2002). ISVP* particles are characterized by (i) a protease-sensitive and hydrophobic conformer of μ1, (ii) release of the μ1 autolytic cleavage fragment μ1N, (iii) elution of the adhesion fiber σ1, (iv) derepression of the viral transcriptase activity, and (v) a substantial loss of infectivity (Borsa et al., 1974; Chandran et al., 2002; Joklik 1972; Odegard et al., 2004).

The thermostability of virions of reovirus strains Type 1 Lang (T1L) and Type 3 Dearing (T3D) is similar, and is conferred by the σ3 protein (Jané-Valbuena et al., 1999; Middleton et al., 2002). While ISVPs of both strains are less thermostable than virions, there is a significant strain difference, with T1L ISVPs being more thermostable than T3D ISVPs (Middleton et al., 2002) This strain difference has been mapped to μ1, using both reassortant viruses and recoated cores containing recombinant T1L or T3D μ1 (Middleton et al., 2002). Heat treatment of wild-type (WT) T1L and T3D ISVPs results in μ1 rearrangement to a protease-sensitive conformer that correlates with the onset of heat inactivation (Middleton et al., 2002). In addition, recoated cores made with an engineered hyperstable μ1 are resistant to undergoing μ1 rearrangement, and are furthermore defective in hemolysis and cell entry (Chandran et al., 2003).

In addition to thermostability, the μ1-encoding genome segment M2 has been shown to determine a strain difference in ethanol resistance between T1L and T3D virions (Drayna and Fields, 1982). Ethanol-resistant (ER) mutants of T3D and Type 3 Abney (T3A) selected by ethanol treatment of virions contain amino acid substitutions in μ1, and ethanol resistance maps to the M2 genome segment by reassortment (Hooper and Fields, 1996; Wessner and Fields, 1993). ER mutants also have a decreased capacity to cause membrane permeabilization as measured by 51Cr release from L929 cells (Hooper and Fields, 1996) and an attenuated pathogenicity in neonatal mice (Derrien et al., 2003).

It has been proposed that ISVPs are kinetically trapped in a metastable state and that a number of stimuli, including heat, lead to equivalent conversions to the same lower-energy state in the ISVP* (Chandran et al., 2002). Structural changes during inactivation have been linked to functional entry-associated rearrangements in other viruses as well. For example, conversion to the 135S entry intermediate of poliovirus can be promoted by receptor binding, by incubating in hypotonic buffer containing divalent cations, or by heating (Curry et al., 1996; Lonberg-Holm et al., 1976; Tsang et al., 2000; Tsang et al., 2001; Wetz and Kucinski, 1991). Conformational rearrangement of the influenza HA protein is promoted during infection by low pH, and a similar rearrangement leading to functional fusion activity occurs when the virus is exposed to heat or urea (Carr et al., 1997; Wharton et al., 1986). Similarly, the murine leukemia virus Env protein, which is promoted to a fusion-active form by receptor binding, can also be activated for fusion by heat, urea, or guanidinium (Wallin et al., 2005).

Rearrangement of μ1 to a protease-sensitive conformer during both heat inactivation and ISVP* conversion (Chandran et al., 2002, 2003; Middleton et al., 2002; Odegard et al., 2004), as well as the finding that particles with a hyperstable mutant of μ1 are affected in their capacity to mediate cell entry (Chandran et al., 2003), suggested to us that heat-resistant (HR) mutants may be useful tools to study reovirus capsid rearrangements and possibly membrane penetration as well. Moreover, reovirus may provide a general model for dissecting the molecular determinants of capsid stability in a nonenveloped virus and may provide insight into means of engineering nonenveloped virus capsids for development of vaccines or oncolytic agents. We therefore undertook a project to select for HR mutants by heat inactivation of ISVPs. In this report, we describe the selection and initial characterizations of nine such mutants, derived from strains T1L and T3D.

Results

A plateau of infectivity after heat inactivation of reovirus ISVPs

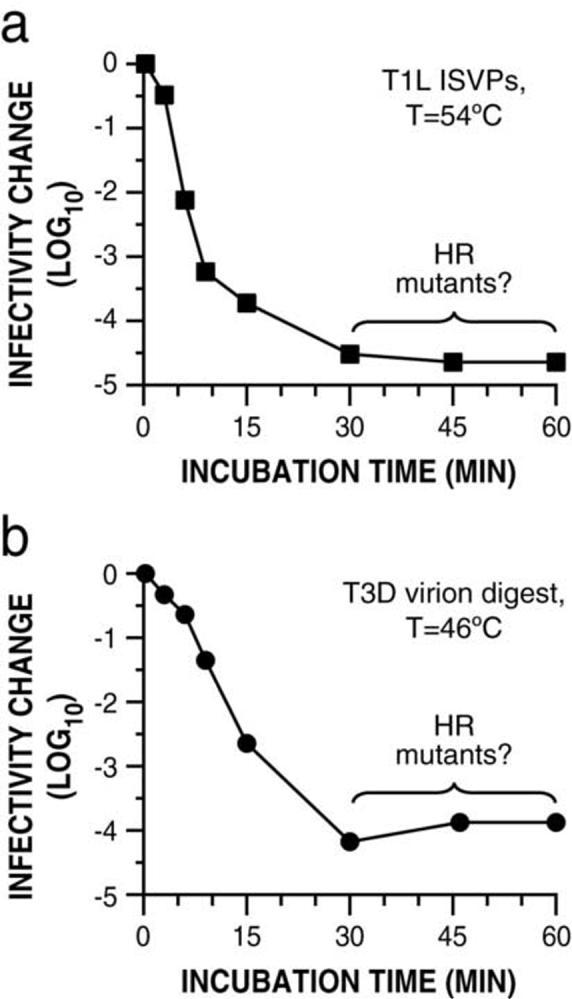

When subjected to heat inactivation over a time course, chymotrypsin (CHT)-generated ISVP preparations of reovirus T1L (purified ISVPs) or T3D (CHT digests of purified virions) were found to include a small subpopulation of infectious particles that survived the treatment, resulting in a long-lasting plateau of residual infectivity (Fig. 1). The size of this subpopulation, 0.01 to 0.001% of the initial titer, is consistent with the hypothesis that HR mutants containing resistance-granting mutations make up a large fraction of the survivors. This hypothesis was proposed from a similar finding in a previous report on heat inactivation of ISVPs (Middleton et al., 2002), but is suggested more clearly here by the extended treatment times (Fig. 1). When the treatments were done at a higher temperature with each parent, the plateau occurred at a lower infectious titer (data not shown), suggesting that fewer of the HR mutants retained infectivity at the higher temperature and therefore that the surviving population was likely to contain a variety of non-equivalent resistance-granting mutations.

Fig. 1.

A plateau of infectivity after heat inactivation of reovirus ISVPs. Purified ISVPs of T1L (a) and CHT digests of T3D virions (b) were subjected to heat treatment at 54°C or 46°C, respectively. At the indicated times, inactivation was halted by chilling on ice, and infectivity was measured by plaque assay. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer) relative to a sample held at room temperature.

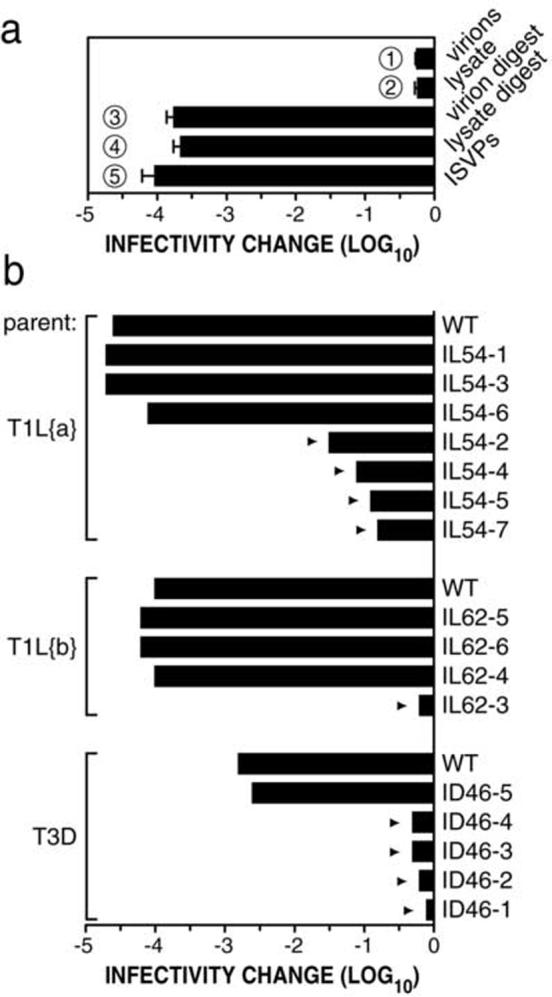

Identification of nine putative HR mutants selected from T1L or T3D ISVPs

To validate CHT treatment of cell-lysate stocks as a method for making ISVPs to select and screen for HR mutants, thereby avoiding the longer process of making purified particles, CHT-treated T1L stocks were treated at 53°C, a temperature at which T1L ISVPs are inactivated to a much greater extent than T1L virions (Middleton et al., 2002). Cell-lysate stocks treated with or without CHT exhibited heat-inactivation behaviors essentially identical to those of purified ISVPs and virions, respectively (Fig. 2a). Similar results (data not shown) were obtained with particles and stocks of reovirus T3D, using 46°C as the temperature to distinguish virions from ISVPs (Middleton et al., 2002).

Fig. 2.

Identification of nine putative HR mutants. (a) Purified T1L virions and T1L cell-lysate stock were treated without CHT (lanes 1 and 2, respectively) or with CHT (lanes 3 and 4, respectively), and subjected to treatment at 53°C for 30 min. Purified T1L ISVPs (lane 5) were included for comparison. Means (± standard deviations) from three experiments are shown. (b) Heat selections were performed with purified T1L ISVPs of two different clones (T1L{a}) and (T1L{b}) at 54 and 62°C, respectively, and with CHT digests of purified T3D virions at 46°C for 30 min. Plaques that survived the initial heat selection were amplified by serial plaque purification and passage in L929 cells. Nine putative HR mutants (arrowheads) were identified by screening CHT-treated passage-3 cell-lysate stocks for heat-resistance at the respective selection temperatures for 30 min. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer), measured by plaque assay, relative to a sample of each virus held at room temperature. Means of two experiments are shown. Clone nomenclature: particle type used in selection (I, ISVP), parent strain (L, T1L; D, T3D), selection temperature, plaque number.

To select for HR mutants, purified T1L ISVPs or CHT digests of purified T3D virions were exposed to inactivation at 54 or 62°C for T1L or at 46°C for T3D. Surviving infectious clones were recovered by serial plaquing and passage in cells, and CHT-treated cell-lysate stocks were then screened for heat resistance. Five of the eleven clones selected from T1L and four of the five clones selected from T3D were found to retain a heat-resistance phenotype (Fig. 2b).

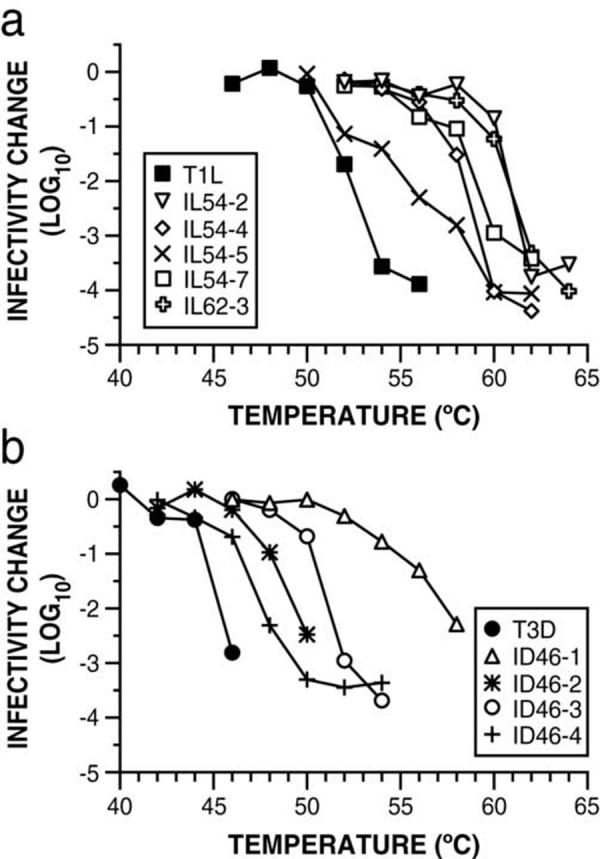

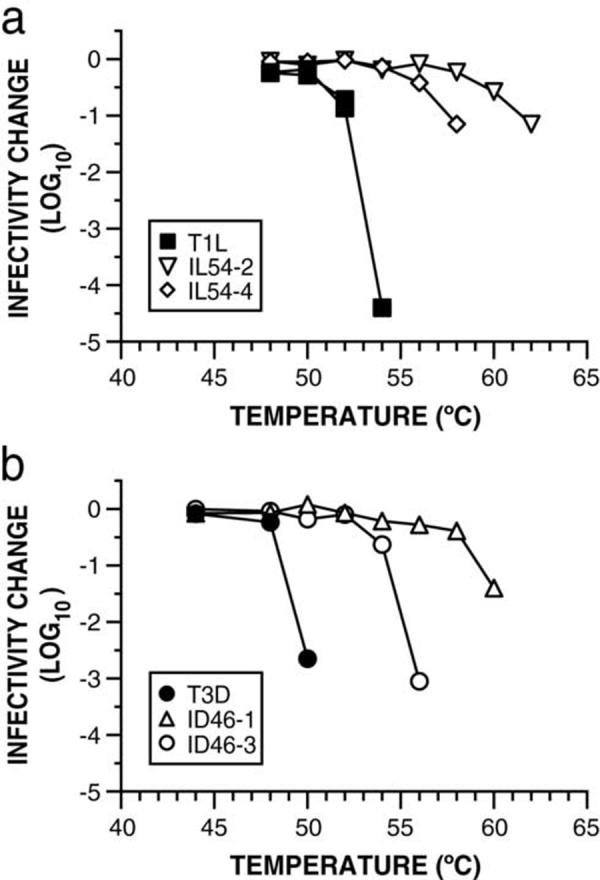

To confirm their heat resistance, CHT digests of purified virions prepared from each of the putative mutants were subjected to treatment over a range of temperatures. In each case, ISVP generation was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (data not shown), ruling out the possibility that the selection had yielded mutants resistant to CHT digestion. The results confirmed that each of the nine clones is a HR mutant (Fig. 3). Inactivation of the five T1L-derived mutants occurred at temperatures 3 to 9°C higher than that required for WT T1L ISVPs (Fig. 3a), and inactivation of the four T3D-derived mutants occurred at temperatures 2 to 12°C higher than that required for WT T3D ISVPs (Fig. 3b). The different degrees of heat resistance exhibited by the different mutants suggest that they contain distinct resistance-granting mutations.

Fig. 3.

HR mutants exhibit varying degrees of heat resistance. CHT digests of purified virions prepared from each wild-type and mutant virus, were subjected to treatment at the indicated temperature for 15 min. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer), measured by plaque assay, relative to a sample of each virus held on ice. Means of two replicates are shown.

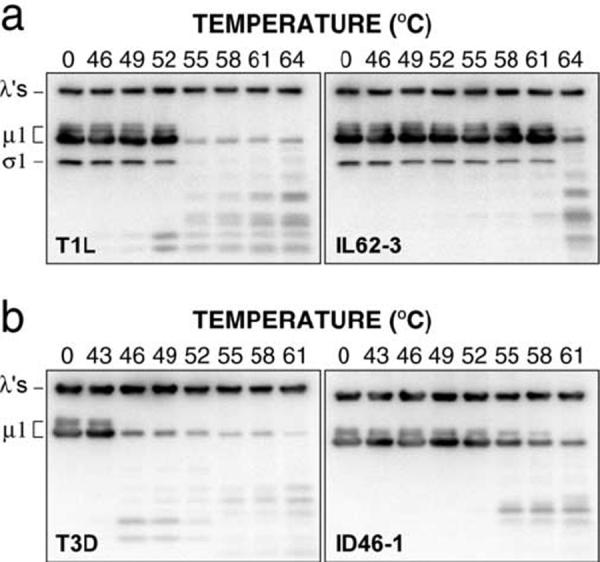

Heat inactivation correlates with onset of μ1 protease sensitivity

Since heat inactivation of WT T1L and T3D ISVPs has been correlated with μ1 rearrangement to a protease-sensitive conformer (Middleton et al., 2002), we hypothesized that the HR mutants selected in this study, in addition to requiring higher temperatures for heat inactivation, would require higher temperatures to elicit μ1 rearrangement. To test this hypothesis, CHT digests of purified virions were subjected to treatment over a range of temperatures, and then incubated with trypsin on ice to assay protease sensitivity of μ1 (Fig. 4). For both mutants IL62-3 and ID46-1, μ1 was found to remain protease resistant after treatment at substantially higher temperatures than their respective WT parents. For all four strains (two HR and two WT), the onset of μ1 protease sensitivity correlated approximately with the onset of heat inactivation (compare Fig. 3 and 4). These results suggest that the heat-resistance phenotypes of IL62-3 and ID46-1, and by inference those of the other HR mutants as well, are a result of μ1 stabilization due to mutations either in μ1 or in other viral proteins that impact μ1 stability.

Fig. 4.

HR mutants are resistant to μ1 rearrangement. CHT digests of purified virions were subjected to treatment at the indicated temperature for 15 min. Samples were chilled on ice, and conformational rearrangement of μ1 was assayed by digestion with trypsin. Following centrifugation to pellet particles, samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting with T1L-virion-specific serum (a) or T3D-virion-specific serum (b).

M2/μ1 sequences of the nine HR mutants

Because the μ1 outer-capsid protein, encoded by the M2 genome segment, determines the different heat-inactivation behaviors of T1L and T3D ISVPs (Middleton et al., 2002), and also because heat inactivation correlates with the onset of μ1 protease sensitivity (Middleton et al., 2002; also see Fig. 4), we hypothesized that each HR mutant contains a mutation in the μ1 protein that confers its heat-resistance phenotype. Toward testing this hypothesis, the M2 gene of each mutant was sequenced from RT-PCR products of viral core-derived RNA transcripts. Six of the nine HR mutants were found to contain single nucleotide changes from the respective parental M2 sequence, resulting in single amino acid substitutions in μ1 (Table 1). The other three HR mutants (one from T1L and two from T3D) were found to contain two substitutions in μ1 (Table 1), and further analysis of these mutants will be undertaken in a later study.

Table 1.

Sequence changes in M2/μ1 of HR mutants derived from reoviruses T1L and T3D

| Virus clonea | M2 nucleotide change(s)b | μ1 amino acid change(s)c |

|---|---|---|

| T1L | – | – |

| IL54-2 | A1404G | K459E |

| IL54-4 | G1650A | D541Ν |

| IL54-5 | C580U, A1141C | A184V, D371A |

| IL54-7 | G1177A | G383Ε |

| IL62-3 | A1404G | K459E |

| T3D | – | – |

| ID46-1 | A1249G | K407R |

| ID46-2 | A1002G, A1321G | T325A, Y431C |

| ID46-3 | C1864U | T612M |

| ID46-4 | G294A, A1321G | E89K, Y431C |

Clone designations are described in the Fig. 2 legend.

Determined by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Designation: nucleotide in the respective WT M2 sequence, nucleotide number, nucleotide in the mutant M2 sequence.

Deduced from each M2 nucleotide sequence. Designation: amino acid in the respective WT μ1 sequence, amino acid number, amino acid in the mutant μ1 sequence.

Among the six “single” HR mutants, five different substitutions were found. Four of the five different substitutions are located in the central, δ-fragment region of μ1, but one of these substitutions, T612M, is in the C-terminal, φ-fragment region (Nibert and Fields, 1992). This is the first evidence that residues in the φ region contribute to ISVP stability. Two of the “single” HR mutants, IL54-2 and IL62-3, contain the same μ1 mutation, K459E, and also showed the most similar heat-inactivation curves (see Fig. 3a). K459E is the same mutation as found in ER mutant JH3 selected from T3A virions (Hooper and Fields, 1996) and is at the same position as the mutation (K459Q) found in ER mutant 3a9 selected from T3D virions (Wessner, and Fields, 1993). Since IL54-2 and IL62-3 were selected from two different plaque-purified clones of T1L, the K459E mutation must have arisen independently in each of them; thus, K459 is a common site for resistance-granting mutations in μ1.

Analysis of heat-resistance phenotypes in recoated particles

Although each of the HR mutants contained at least one substitution in its μ1 protein, it was possible that these mutations did not determine the heat-resistance phenotypes. We therefore used recoated cores (RCs) (Chandran et al., 1999, 2001) to test the role of the μ1 mutations in conferring thermostability. For the purposes of this study, we restricted attention to two mutants from each parent containing single changes in μ1: IL54-2/IL62-3, K459E; IL54-4, D541N; ID46-1, K407R; and ID46-3, T612M. Recombinant μ1 proteins containing these mutations, as well as WT T1L and T3D μ1, were expressed in insect cells along with WT T1L σ3 and σ1, and used to make RCs. SDS-PAGE confirmed that each preparation of RCs contained virion-like levels of μ1 and σ3 and that CHT treatment of the RCs generated ISVP-like particles (pRCs) (Chandran et al., 1999, 2001) from each preparation (data not shown).

We have previously shown that pRCs containing WT T1L or T3D μ1 approximate the heat-resisatnce behaviors of T1L and T3D ISVPs, respectively (Middleton et al., 2002). To determine if the μ1 substitutions found in the HR clones (see Table 1) confer heat resistance, pRCs containing either WT or mutant μ1 were subjected to treatment over a range of temperatures. All of the pRCs containing mutant μ1 were found to be more heat resistant than pRCs containing the respective WT μ1 (Fig. 5). Moreover, the extent to which each mutant μ1 stabilized the pRCs relative to the WT μ1 was very similar to that seen with ISVPs (compare Fig. 3 and 5). These results provide strong evidence that for each of the four HR mutants evaluated in this manner, the mutation in its μ1 protein is the major determinant of its heat-resistance phenotype.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of heat-resistance phenotypes in recoated particles. Recoated cores (RCs) were made with recombinant WT T1L or T3D μ1, or μ1 containing the mutations found in the indicated mutant clones. RCs were treated with CHT to generate ISVP-like particles and subjected to treatment at the indicated temperatures for 15 min. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer), measured by plaque assay, relative to a sample of each RC preparation held on ice. Means of two replicates are shown.

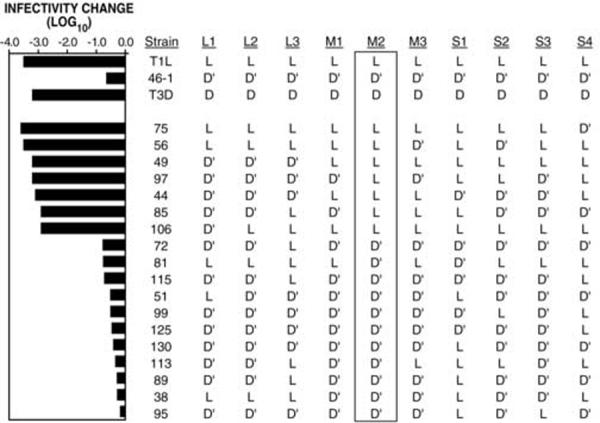

Reassortant analysis of the heat-resistance phenotype of ID46-1

To confirm mapping of the HR phenotype to M2/μ1, reassortant analysis was performed for mutant ID46-1. Reassortants were generated by co-infection with ID46-1 and WT T1L. Plaque-purified progeny clones were screened for reassortment by determining the origin of each genome segment according to its relative mobility in polyacrylamide gels. Clones determined to be reassortants were then screened for heat resistance by subjecting them to treatment at 53°C, which inactivates both WT T1L and WT T3D ISVPs significantly more than ID46-1 ISVPs (Fig 6). The heat-resistance phenotype was found to map clearly and without exception to the μ1-encoding M2 genome segment (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Reassortant analysis of the heat-resistance phenotype of ID46-1 Reassortants were generated by co-infection of T1L and HR mutant ID46-1. Reassortants were screened for heat resistance by subjecting CHT-treated passage-3 lysate stocks to 53°C for 15 min. Infectivity change is expressed as log10(infectious titer), measured by plaque assay, relative to a sample kept on ice. L: genome segment derived from WT T1L; D: genome segment derived from WT T3D; D’: genome segment derived from ID46-1. A representative experiment is shown.

Kinetic analyses and Arrhenius plots for HR-mutant ISVPs

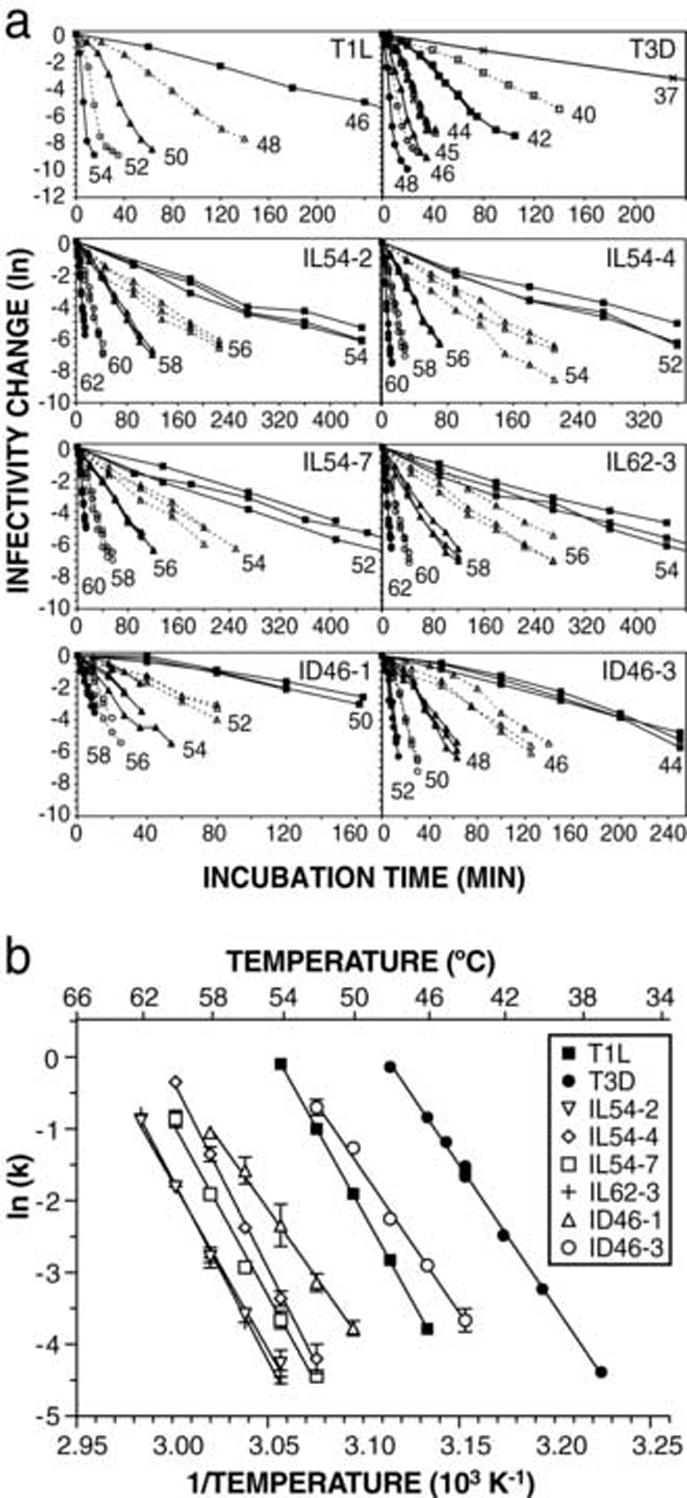

For each HR mutant containing a single mutation in μ1, kinetic rate constants of inactivation were determined by performing heat-inactivation time courses with CHT digests of purified virions at a number of different temperatures at which the inactivation rate was practically measurable. Consistent with previous results generated with WT ISVPs (Middleton et al., 2002), all of the time courses approximated first-order reaction kinetics (Fig. 7a). As a result, the inactivation rate k at each temperature could be estimated by ln(I/I0)=-kt, where I is the infectious titer, I0 is the initial infectious titer, and t is the treatment time. In this manner, the inactivation rate of each HR mutant was found to be dependent on temperature and to be well modeled by the Arrhenius equation, in which ln(k) is a linear function of the reciprocal temperature (Fig. 7b). As previously noted for the inactivation curves in Fig. 3, the behavior of each HR mutant appeared distinct, with the exception of mutants IL54-2 and IL62-3, which share the same μ1 mutation and also showed overlapping Arrhenius plots. Furthermore, the relative shifts in the Arrhenius plot for each mutant correlated with the degree of heat resistance (compare Fig. 3 and 7b).

Fig. 7.

Kinetic analysis of heat inactivation of HR mutants. (a) Time courses of heat inactivation were performed with CHT digests of purified virions, at the indicated temperatures. At each time point, aliquots were taken out and immediately diluted in ice-cold buffer. Infectivity change is expressed as ln(infectious titer), relative to the first time point (0 or 0.25 min). For clarity, the longest time courses are shown truncated in some of the panels. (b) Arrhenius plots were constructed by detemining rate constants of inactivation (k) at each temperature, from the slopes of the time courses shown in panel a. Each point represents the mean (± standard deviation) of three or more determinations, except WT T1L and T3D, for which single replicates are shown. Lines represent the nonlinear-regression fit of the Eyring equation (see text). Data for WT T1L and T3D are reproduced from Middleton et al. (2002).

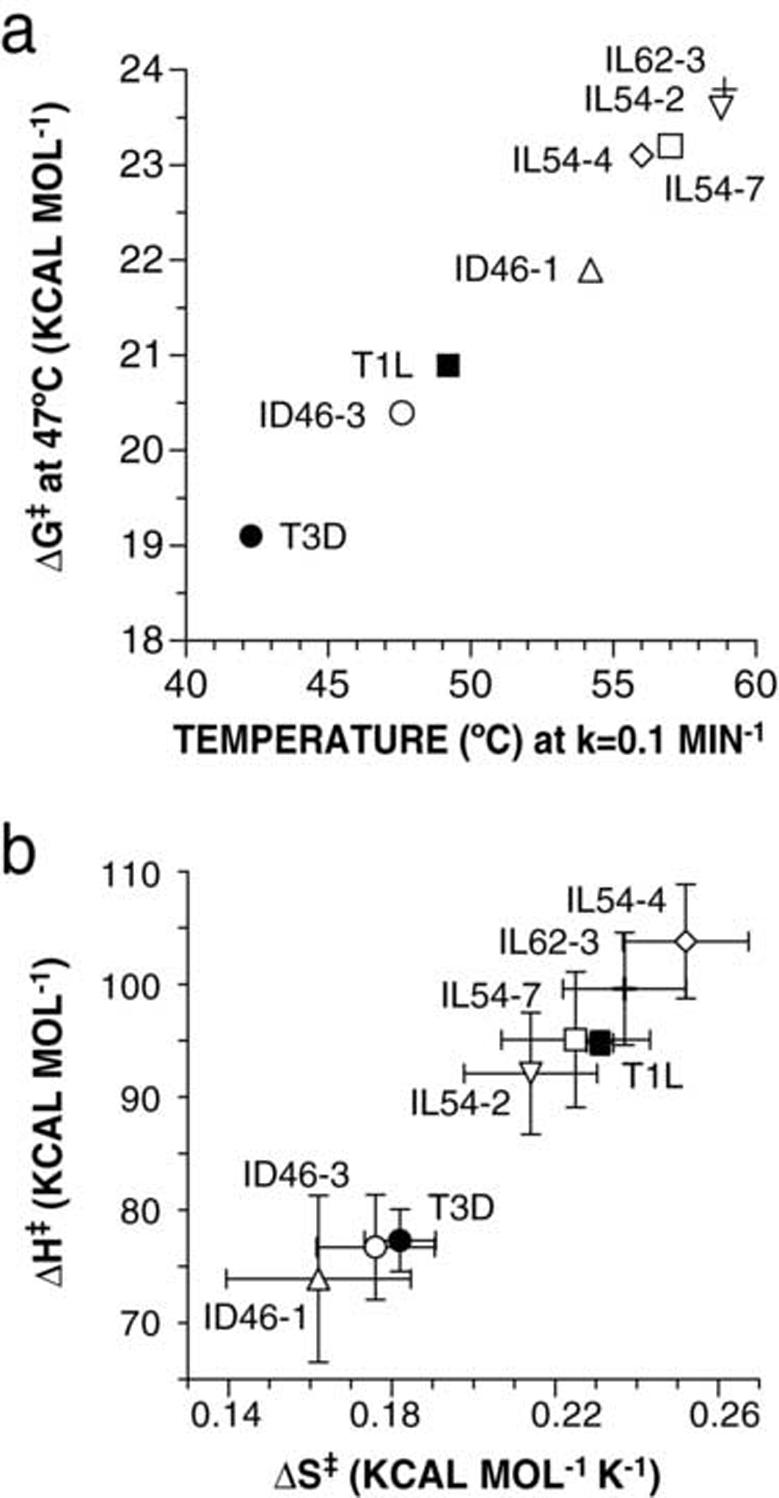

The Gibbs free energy of activation ΔG‡ for each tested mutant was next calculated by nonlinear-regression fitting of the Arrhenius plots with the Eyring equation from transition-state theory, ln(k)=ln(kbT/h)-ΔH‡/RT+ΔS‡ b /R, in combination with the thermodynamics equation ΔG‡=ΔH‡-TΔS‡, where k is the rate constant, kb is Boltzmann’s constant, h is Planck’s constant, ΔH‡ is the enthalpy of activation, ΔS‡ is the entropy of activation, R is the ideal gas constant, and T is the temperature in K. Inactivation rates of both WT and HR ISVPs were practically measurable over only a narrow range of temperatures (∼10°C), as evident from the inactivation time courses as well as from the steep slopes of the Arrhenius plots (see Fig 7); as a result, the values for ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ obtained from these data are subject to fairly large experimental errors (Table 2). However, since the ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ values for each virus derive from the slope and y-intercept of same fitted line, the associated errors are positively correlated and partly offset each other in calculating ΔG‡, yielding ΔG‡ values that are more precise than those of the component parameters. All of the mutants were found to have calculated ΔG‡ values greater than those of their respective parents, and the most thermostable mutants were found to have the highest ΔG‡ values (Table 2). This can be illustrated by plotting ΔG‡ at 47°C for each virus strain as a function of the temperature at which that strain would have an inactivation rate of 0.1 min-1 (Fig. 8a). In the terms of transition-state theory, therefore, thermostability-granting mutations in μ1 lead to an increase in the free-energy barrier that must be overcome on the way to thermal inactivation. In all cases, the increased ΔG‡ values appear to result from a combination of changes in both ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ (Table 2), with the mutants’ values clustering near those of the respective parent in a plot of ΔH‡ versus ΔS‡ (Fig. 8b).

Table 2.

Values derived from Arrhenius plots for reoviruses T1L and T3D and their HR mutants

| Virus isolate | ΔH‡a (kcal mol-1) | ΔS‡a (kcal mol-1 K-1) | ΔG‡b (kcal mol-1) | ΔΔG‡c (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1L | 94.8 ± 1.1 | 0.231 ± 0.003 | 20.9 | - |

| IL54-2 | 92.1 ± 5.4 | 0.214 ± 0.016 | 23.6 | 2.7 |

| IL54-4 | 104 ± 5.1 | 0.252 ± 0.015 | 23.1 | 2.2 |

| IL54-7 | 95.1 ± 6.0 | 0.225 ± 0.018 | 23.2 | 2.3 |

| IL62-3 | 99.6 ± 5.0 | 0.237 ± 0.015 | 23.8 | 2.9 |

| T3D | 77.3 ± 2.8 | 0.182 ± 0.009 | 19.1 | - |

| ID46-1 | 73.9 ± 7.4 | 0.162 ± 0.023 | 21.9 | 2.8 |

| ID46-3 | 76.7 ± 4.7 | 0.176 ± 0.015 | 20.4 | 1.3 |

Errors represent 95% confidence intervals from nonlinear-regression fits of the Eyring equation to the Arrhenius plots.

Calculated at 47°C

With respect to each WT parent

Fig. 8.

Gibbs free energy of activation of HR mutants. Enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡) and entropy of activation (ΔS‡) were estimated from the Arrhenius plots by fitting the Eyring equation (see Fig 7). (a) Gibbs free energy of activation (ΔG‡) was calculated at 47°C and is shown as a function of the temperature that would yield an inactivation rate of 0.1 min-1, determined by linear regression of the Arrhenius data. (b) Relative contributions of ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ are shown for each mutant. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals from nonlinear-regression fits of the Eyring equation to the Arrhenius plots.

Infectivity phenotypes of HR mutants

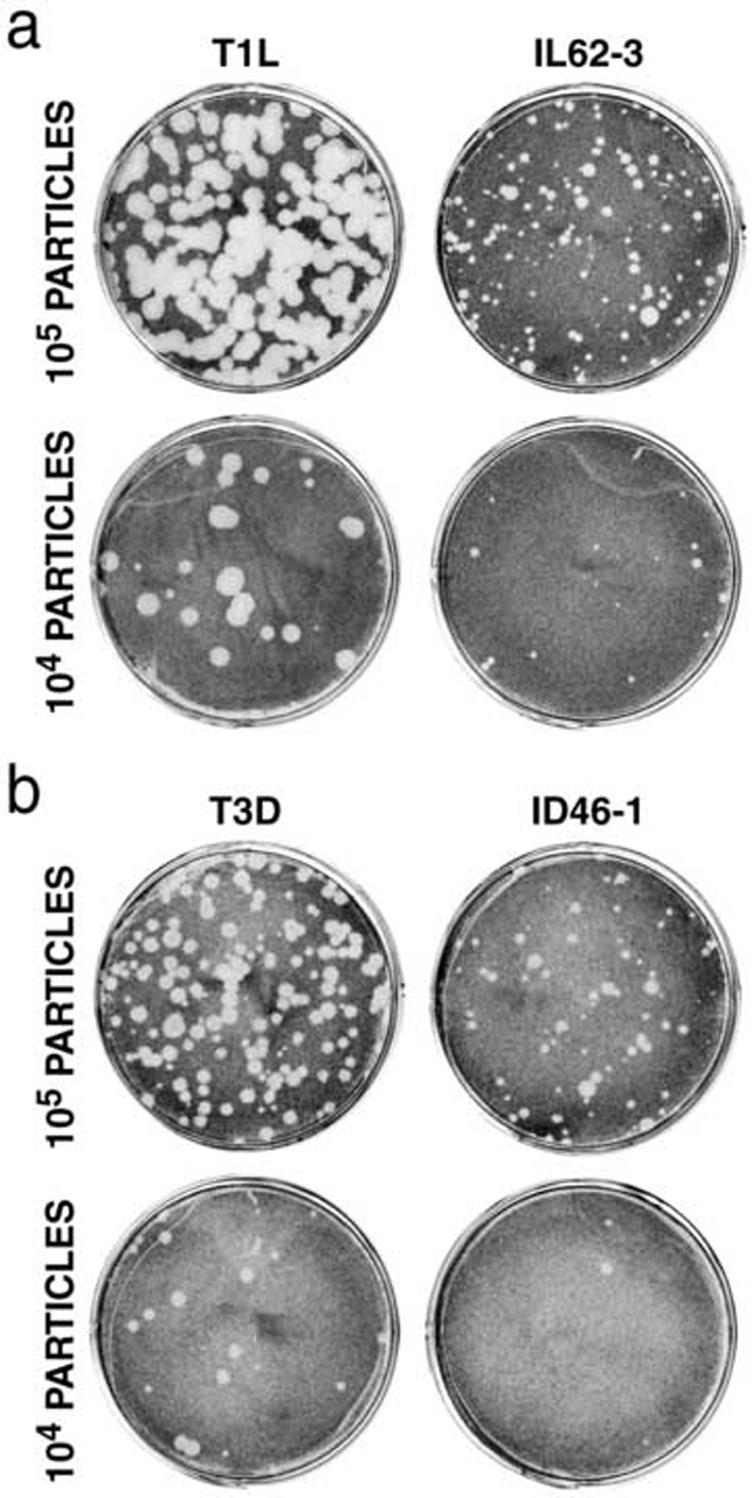

Although the HR mutants exhibit delayed μ1 conformational change in vitro, we were unable to detect consistently significant delays in single-cycle growth curves or onset of viral protein synthesis following cell entry (data not shown). Since survivors of the heat selection were necessarily subjected to plaquing and amplification, it is likely that any particle with a significant entry/growth defect either would not have been recovered or would have acquired a reversion or pseudoreversion mutation during culture. However, some of the HR mutants were observed to have smaller plaques and slightly higher particle/PFU values than their respective WT parents (Fig. 9), suggesting that they may have relatively small defects in entry/growth or spread/killing that are made apparent in the plaque assay.

Fig. 9.

Plaque size of HR mutants. L929 cell monolayers were infected with 104 or 105 purified virions and overlayed with media/agar containing CHT. At 48 h (a) or 73 h (b) post-infection, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet.

Discussion

HR mutants were selected by heat inactivation of reovirus ISVPs. Of the sixteen clones that survived the selection and passage into stocks, only nine remained heat resistant (see Fig. 2). There are reasonable explanations for this. First, because two of the three selections were done at temperatures at which virions would have mostly survived (Middleton et al., 2002), a small number of virions remaining in the ISVP preparations could have contributed to the survivors. Second, WT ISVPs in certain microenvironments within the treatment volume, such as particles in aggregates or trapped at the air-liquid interface, could have had a greater chance of survival. Third, hybrid particles with HR capsids but WT genomes could have been present in the ISVP preparations; such particles could have survived the selection, but would have displayed a WT phenotype after plaquing and amplification. Fourth, some of the HR mutants whose mutations could have caused them to be unfit for growth in culture could have reverted to a WT-like phenotype during plaquing and amplification.

When examined more carefully, the nine HR mutants were found to have varying degrees of heat resistance (see Fig. 3), and M2 sequencing revealed that each contains one or two amino acid substitutions in outer-capsid protein μ1 (see Table 1). Using reassortant analysis, M2/μ1 was identified as the genetic determinant of heat resistance in mutant ID46-1 (see Fig. 6). Additionally, the heat-resistance phenotypes of this mutant and three others were mapped to μ1 using recoating genetics (Chandran et al., 1999, 2001; Jané-Valbuena et al., 1999) (see Fig. 5), illustrating the utility of recoating as a useful addition to reassortment for assigning phenotypes to sequence changes in the outer-capsid proteins. Because T3D ISVPs are much less thermostable than T1L ISVPs, as dictated by sequence differences in their μ1 proteins (Middleton et al., 2002), we initially thought that T3D might acquire heat resistance through mutations in μ1, making it more similar to T1L, whereas T1L might acquire heat resistance through mutations in another viral protein, such as λ2 or σ1. The consistent identification of HR mutations in the μ1 proteins of both T1L and T3D, however, provides further evidence that μ1 is an important, and perhaps the main, regulator of outer-capsid stability in the ISVP.

Our method for selecting HR mutants did not ensure that each would have an independent origin: four were selected from the same T1L clone (T1L{a}) and four others from the same T3D clone (see Fig. 2). The mutants within each group could thus have been “sisters”, which shared the same mutation because they descended from the same HR clone that arose spontaneously in the respective parent stocks (Luria et al., 1943). Nevertheless, most of the HR mutants were found to have distinct M2/μ1 mutations. Although IL54-2 and IL62-3 share the same M2/μ1 mutation (A1404G/K459E), they were selected from different parent clones and hence cannot be sisters. The two T3D-derived mutants that have two M2/μ1 mutations, ID46-2 and ID46-4, were selected from the same parent clone and share one M2/μ1 mutation in common, A1321G/Y431C. If this is the resistance-granting mutation in each, then these clones may be sisters that acquired different second mutations during plaquing and amplification.

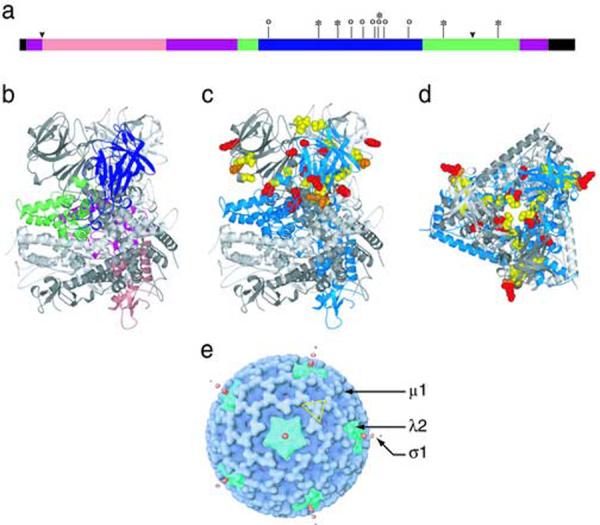

Among the six HR mutants with single changes in μ1, the five different substitutions are all located within a central portion of the μ1 primary sequence from residues 383 to 612 (Fig. 10a). The locations of these mutations in the sequence partly overlap those reported for ER mutants that were selected from reoviruses T3D and T3A (Hooper and Fields, 1996; Wessner and Fields, 1993) and were further shown by Hooper and Fields to be thermostable as ISVPs. All of the ethanol-resistance mutations fall between positions 319 and 497 in the μ1 primary sequence (Fig. 10a), and are also within the β-strand-rich “domain IV”, or “top domain”, of the μ1 trimer (Liemann et al., 2002) (Fig. 10b, c). Three of the newly characterized HR mutations are also within this region, but the other two are within upper regions of the α-helix-rich “domain III” (Fig. 10a) that lie just below domain IV in the μ1 trimer structure (Liemann et al., 2002) (Fig. 10b, c). HR mutation T612M is within the part of domain III that comes from the C-terminal φ region of μ1 (Nibert and Fields, 1992) (see Fig. 10a), revealing that this region also contributes to ISVP stability.

Fig. 10.

Locations of the HR mutations. (a) Locations of the single HR mutations from this study are shown on the μ1 primary structure (asterisks). Locations of previously characterized ER mutations (Wessner and Fields, 1993; Hooper and Fields, 1996) are shown for comparison (circles). μ1 structural domains (Leimann et al., 2001) are indicated (pink: domain I; purple: domain II; green: domain III; blue: domain IV; black: not seen in crystal structure). Cleavage junctions are marked by arrowheads: μ1N/μ1C at left and δ/φ at right. (b) The location of the four μ1 structural domains are shown for a single μ1 subunit in the trimer, color coded as in panel a. (c) The locations of HR and ER mutations are highlighed in the μ1 structure by a space-filling representation. HR mutations from this study, red; previously characterized ER mutations, yellow; amino acid K459, at which both HR and ER mutations have been selected, orange. (d) Top view of the trimer, with mutations highlighted as in panel c. (e) Locations of μ1, λ2, and σ1 proteins in a cryo-EM reconstruction of the ISVP (Dryden et al., 1993). A μ1 trimer, in approximately the same orientation as in panel d, is outlined in yellow.

In the upper parts of the μ1 trimer, domains III and IV from each subunit are wound around the threefold axis (see Fig. 10b), and as an early step in the rearrangements that precede membrane penetration, these domains are throught to unwind around this axis and separate from the other subunits (Liemann et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006). These changes are then thought to be followed by further rearrangements in the bottom parts of the trimer (domains I and II), including autocleavage and release of the myristoylated μ1N peptide (Nibert et al., 1991, 2005; Odegard et al., 2004). All μ1 contacts with λ2 occur through domains I and II (Zhang et al., 2005) (see Fig. 10e), suggesting that effects on λ2 that result in elution of σ1, and perhaps transcriptase derepression as well, may occur only after rearrangements have progressed to these bottom parts of the μ1 trimer. Conversion to the ISVP* particle is irreversible, but there may be intermediate stages of μ1 rearrangement that are reversible. Unwinding of the trimer top, for example, may be reversible, until a “point of no return” is reached, and further rearrangements then lead irreversibly to the ISVP*. According to this model, then, the trimer’s upper portions (domains III and IV) have an important role as gatekeepers for irreversible changes in the bottom portions (domains I and II). We propose that the resistance-granting mutations in domains III and IV serve to stabilize the μ1 trimer by interfering with this unwinding.

How might the specific mutations in μ1 have their stabilizing effects? Reviews of other thermostabilized proteins suggest that stabilization can occur through a variety of complex effects that are often hard to dissect or interpret for any given mutation (Lehmann and Wyss, 2001; Perl and Schmid, 2002; Querol et al., 1996; van den Burg and Eijsink, 2002; Vieille and Zeikus, 2001). It is common in these other proteins for thermostabilizing mutations to target solvent-exposed residues, instead of ones buried in the hydrophobic core (Perl and Schmid, 2002; Vieille and Zeikus, 2001), and indeed all of the substituted residues in the single HR mutants described in this study and ER mutants described previously have portions of their R groups exposed to solvent in the μ1 trimer (data not shown). In some of the HR and ER mutants, solvent exposure is not on the outer surface of the μ1 trimer, but within the solvent channel that runs along the threefold axis through the middle of the trimer (see Fig. 10d). In the reviews of other thermostabilized proteins, mutations at solvent-exposed residues are concluded to increase stability by various enthalpic mechanisms including increased hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, or van der Waals contacts, as well as by solvent effects that are largely entropic (Lehmann and Wyss, 2001; Perl and Schmid, 2002; Querol et al., 1996; van den Burg and Eijsink, 2002; Vieille and Zeikus, 2001). A mix of enthalpic and entropic contributions appears likely to explain the thermostabilization of HR mutants in this study as well (see below).

For oligomeric proteins specifically, increased thermostability is often achieved by mutations that strengthen intersubunit contacts (Vieille and Zeikus, 2001), and the same appears true for μ1. Interestingly, the μ1 mutations fall into two general classes. One class comprises mutations—G383E, D541N, and T612M among the HR mutants and A319E and Q440K among the ER mutants—that are located near intersubunit contacts within the μ1 trimer (see Fig.10d). These mutations are often exposed to solvent within the central channel of the trimer. It thus appears likely that these mutations increase stability by directly strengthening intratrimer contacts. Recently described pairs of disulfide-bonding mutations in μ1 domain IV are thought to stabilize the trimer in this same way (Zhang et al., 2006). The second class of mutations—K407R and K459E among the HR mutants and V425F, P454R, K459E, K459Q, Y466C, and P497S among the ER mutants—are not consistently found near intersubunit contacts within the μ1 trimer and are not exposed to solvent in the central channel; instead, they are exposed to solvent on the outer surface of the μ1 trimer, generally close to where domains IV from adjacent trimers make local quasi-twofold contacts within the outer capsid (Liemann et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005) (see Fig. 10d, e). Thus, this second class of mutations may strengthen these local twofold contacts, thereby stabilizing the capsid lattice and the constituent trimers in turn.

The inactivation of reovirus ISVPs approximates first-order kinetics and is well modeled by the Arrhenius equation (Middleton et al., 2002). This also holds true for the ISVPs of HR mutants in this study (see Fig. 7). For an irreversible process such as this, some understanding of the energetics may be obtained from transition-state theory. The total energy needed for the ISVP to change from ground to transition state is the Gibbs free energy of activation ΔG‡, which can be calculated from its components, the enthalpy of activation ΔH‡ and the entropy of activation ΔS‡. Our results suggest that the increased stability of the HR mutants does not usually result from a change in either ΔH‡ or ΔS‡ alone, but from changes in both (see Table 2 and Fig. 8b) that compensate to yield a greater ΔG‡. The increases in ΔG‡ range between 1 and 3 kcal mol-1 for the HR mutants characterized here, with respect to each appropriate WT parent (see Table 2 and Fig. 8a). Thus, relatively modest changes in ΔG‡ can account for significant differences in the stability of reovirus ISVPs over a practical range of temperatures. Using a similar kinetic analysis, the stabilizing effects of two antiviral capsid-binding compounds on poliovirus, which also exhibits a first-order heat-induced transition from the native 160S particle to the 135S intermediate, led to increases in ΔG‡ of 0.6 and 2.1 kcal mol-1, respectively (Tsang et al., 2000). In comparison, the difference in stability between meso- and thermophilic enzymes is in the range of ΔΔG = 5 to 7 kcal mol-1 (Querol et al., 1996).

How close have we come to saturating the sites at which mutations in μ1 can render ISVPs more thermostable? Is there a limit to the degree of thermostabilization that is consistent with continued infectivity of ISVPs? These are just two of the questions that we hope to address in future studies. In closing, we affirm that reovirus provides an interesting and tractable system for exploring the genetic and molecular basis of viral capsid stability, as well as the conformational rearrangements that accompany cell entry by a nonenveloped virus.

Materials and methods

Cells

Spinner-adapted mouse L929 cells were grown in Joklik’s modified minimal essential medium (Irvine Scientific) supplemented to contain 2% fetal bovine serum and 2% bovine calf serum (HyClone Laboratories) in addition to 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Irvine Scientific). Spodoptera frugiperda clone 21 and Trichoplusia ni TN-BTI-564 (High Five) insect cells (Invitrogen Technologies) were grown in TC-100 medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented to contain 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

Virions, ISVPs, and cores

Virions of reoviruses T1L, T3D, and the HR mutants in Table 2 were grown in spinner cultures of L929 cells, purified according to the standard protocol (Furlong et al., 1988), and stored in virion buffer (VB, pH 7.5: 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 or 20 mM Tris). CHT digests of cell-lysate stocks were made by diluting the stocks 1/10 in VB and treating with 200 μg/ml TLCK-treated α-CHT (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C. Digestion was stopped by addition of ethanolic phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich) to 1 or 2 mM and incubation on ice for at least 10 min. Nonpurified ISVPs were obtained by digesting purified virions at a concentration of 1×1012 to 5×1012 particles/ml with CHT (200 μg/ml), for 10 to 30 min at 32 or 37°C. Digestion was stopped by addition of ethanolic phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride to 1 mM and incubation on ice for at least 10 min. Production of ISVPs was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Purified cores for use in recoating were prepared from T1L virions as described elsewhere (Chandran et al., 1999), except that virions were digested with 250 μg/ml CHT for 2 to 4 h. Particle concentrations were estimated by A260 (Coombs, 1998) or by SDS-PAGE.

Selections and stocks of HR mutants

ISVPs derived from two independently plaqued clones of T1L, {a} and {b}, were used for selections. For T1L{a}, purified ISVPs in VB at 4×109 particles/ml were treated for 60 to 120 min at 54°C before plaquing on L929-cell monolayers at 37°C to recover putative HR mutants. For T1L{b}, purified ISVPs in VB at 2×109 particles/ml were treated for 20 min at 62°C before plaquing as above. For the T3D clone, nonpurified ISVPs (generated by CHT digestion for 30 min at 32°C) in VB at 5×1011 particles/ml were treated for 30 min at 46°C before plaquing as above. After the initial plaquing, each putative HR mutant from T1L{b} was serially plaqued twice more before being grown into passage-1 to -3 stocks in L929-cell monolayers at 37°C. Each putative HR mutant from T1L{a} and T3D, on the other hand, was first grown into passage-1 to -2 stocks in L929 cell monolayers before being serially plaqued twice more from the passage-2 stock. These triply plaque-purified clones were then again grown into passage-1 to -3 stocks in L929-cell monolayers at 37°C. Passage-2 or -3 stocks of triply plaque-purified clones were used for experiments or for growing virions for purification. Plaques were picked into 0. 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.5:137 mM NaCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl) supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 (PBS-Mg), and then frozen and thawed once. Infections were done at each passage level using an 0.5-ml inoculum and a virus-attachment period of 1 h at room temperature. Passage-1 stocks were grown in 25-cm2 culture flasks with 5 ml of medium (supplemented Joklik’s as described above), and passage-2 and -3 stocks were grown in 75-cm2 flasks with 15 ml of medium. Cell-lysate stocks at each passage level were generated by two cycles of freezing and thawing after ∼90% of cells had detached from the flasks.

Amplification and sequencing of the M2 genome segment of HR mutants

Amplification and sequencing was done as described (McCutcheon et al., 1999) with the following changes. Nonpurified cores of each HR mutant where generated by first digesting virions to ISVPs as described above. The nonpurified ISVPs where incubated with 0.2 M CsCl for 30 to 90 min and then digested to cores by digestion with 200 μg/ml trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C. Digestion was stopped by adding soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich) to 600 μg/ml. Generation of cores was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Plus-strand transcripts of each HR mutant were generated using 30 μ1 of the nonpurifed core digest. These transcripts served as a template for synthesis of full-length cDNA copies of each M2 gene segment. Primers were designed from the published sequences for the M2 genome segments of strains T1L and T3D (Jayasuria et al., 1988; Wiener and Joklik, 1988). Reverse transcription was done using AMV reverse trancriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified by PCR using the same primer used in reverse transcription and an additional primer. A mixture of Taq and Pwo polymerases (Expand Long Template PCR System, Boehringer-Mannheim) was used to reduce the frequency of copy errors. PCR products from four reactions were purified by gel and combined before sequencing. DNA sequencing was performed at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center DNA Sequencing Facility using cycle sequencing protocols with fluorescent dideoxy terminators (Applied Biosystems/Perkin-Elmer). The first two sequencing reactions were performed using the same primers as for PCR amplification. Primers for subsequent sequencing reactions were designed from the published sequence for T1L and T3D M2. Sequencing reactions were conducted over both strands of the PCR product to confirm changes.

Recoated cores

Recoated cores (RCs) were made with baculovirus-expressed WT T1L σ3, WT T1L σ1, and either WT T1L μ1, WT T3D μ1, or mutant μ1, as described previously (Chandran et al., 1999) with the following changes. Cores were incubated with insect-cell lysates for 2 to 4 h to assemble the outer capsid, and RCs were purified by banding on CsCl step gradients (ρ=1.30-1.45 g/cm3). Baculoviruses expressing mutant μ1 were made from the M2 genome segments cloned from each mutant by reverse transcription and PCR as described below.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) as described elsewhere (Chandran and Nibert, 1998). Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Sigma-Aldrich). For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and detected with rabbit T1L- or T3D-virion-specific serum (Virgin et al., 1998) (1:2000), followed by rabbit-specific donkey immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch) (1:5000). Antibody binding was detected with Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagents (PerkinElmer) and a Typhoon scanner (Amersham) in chemiluminescence mode.

Plaque assays

Plaque assays were done as described previously (Furlong et al., 1988). For some experiments, this protocol was altered by washing the monolayers with 2 ml of PBS-Mg prior to the 1-h virus-attachment incubation, after which the monolayers were covered with 2 ml of 1% Bacto Agar (DIFCO) and serum-free medium 199 (Irvine Scientific) containing 10 or 12 μg/ml CHT (CHT plaque assay). Plaques were counted 2 to 4 days later, depending on the reovirus strain. For imaging plaques, CHT plaque assays were first fixed by incubating with 1 ml of 10% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 45 min at room temperature. The agar ovelays were then peeled off, and cells were stained by covering with 0.05% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10% ethanol for 45 min at room temperature, followed by two washes with water.

Heat inactivations

Inactivation experiments with nonpurified ISVPs were conducted as described previously (Middleton et al., 2002). Briefly, virion buffer was preheated at the experimental temperature in a water bath for 30 min. ISVPs in virion buffer were then added to a final concentration of 2×109 particles/ml and mixed by pipeting. Prior to an aliquot of the inactivation mixture being removed at each time point, the entire mixture was again mixed by pipeting. Aliquots were harvested over the length of time required to reduce the titer to 0.1% of starting levels. Upon harvesting, aliquots were immediately diluted in cold PBS-Mg. In most cases, a 111-μl aliquot was added to 1 ml of cold PBS-Mg at this step; however, for samples expected to have low titers, a 200-μl aliquot was added to 600 μl of cold PBS-Mg at this step. Each of these samples was then further diluted and subjected to plaque assay as described above. Inactivation experiments with pRCs were done by first digesting with CHT to yield ISVP-like particles (pRCs) as described above for nonpurified ISVPs. pRCs were diluted in VB to a final concentration of 1×1012 particles/ml, and then subjected to the treatment temperature. At the indicated time, samples were chilled on ice and diluted with PBS-Mg for plaque assay.

Protease-sensitivity assay

For analysis of μ1 rearrangement, heat inactivations were performed with nonpurified ISVPs at a final concentration of 5×1012 particles/ml, in VB. After heat treatment for 15 min, samples were chilled in an ice bath, and digested with 100 μg/ml trypsin for 45 min on ice. Digestion was stopped by addition of soybean trypsin inhibitor to 300 μg/ml and incubation on ice for at least 15 min. Virus particles were pelleted by centrifugation at 16000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and resuspended in 1× Laemmli sample buffer for SDS-PAGE.

Generation of reassortants

Reassortants were generated by co-infecting L929 cell monolayers in 2-dram glass vials with passage-2 stocks of T1L and ID46-1. Separate co-infections were performed with T1L:ID46-1 multiplicity ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 1:5, with a total of 30 PFU/cell in each case, and inoculation volumes of 1 ml. Virus was allowed to adsorb at room temperature for 2 h, after which the cells were washed three times with PBS-Mg, covered with 2 ml of media as described above for L929 cells, and incubated at 37°C. At 24 h post-infection, lysate stocks were made by two cycles of freezing and thawing. CHT plaque assays were performed as described above, and plaques were picked over the course of days 3 through 5. Plaques were picked into 0.5 ml of VB and then frozen and thawed twice. A second plaque purification was performed by picking plaques from plaque assays of either dilutions of the first plaque or dilutions of a “0-passage” stock generated from the first plaque. The second plaques were then used to generate passage-1 and -2 cell-lysate stocks. The genotypes of each reassortant were determined by infecting L929 cells in 6-well plates with 100 μl of passage-2 stock, and isolating RNA at 30 h post-infection using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Samples were disrupted at 60°C for 5 min, and separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide to visualize double-stranded RNA, and the identity of each genome segment was determined from its mobility by comparison to marker lanes with purified T1L or T3D virions.

Parameter estimation

Rate constants were estimated from linear regression of time course data. In some cases, time points from the beginning and/or the end of the time course were omitted from the analysis, in order to remove an initial lag or a final plateau, and restrict attention to the linear portion of the time course. ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ were estimated by a nonlinear-regression fit to the Eyring equation using Kaleidagraph v3.51 or GraphPad Prism v3.02. For each HR mutant, rate constants were determined from three or four time courses, and replicates were considered individually in the regression fitting. For WT T1L and T3D, rate constants determined by Middleton et al. (2002) were used.

Molecular graphics

The crystal-structure images in Fig. 10 were created using PyMol v0.95 (DeLano Scientific).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Laura Breun, Elaine Freimont, and Becky Margraf for technical assistance. We also thank Kartik Chandran, Steve Harrison, Tijana Ivanovic, and Lan Zhang for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported in part by NIH grants F31AI064142 to M.A.A., R21 AI071197 to J.Y., and R01 AI46440 to M.L.N.; by NSF grant EIA-0331337 to J.Y.; and by a grant from the Lucille P. Markey Charitable Trust to the Institute for Molecular Virology at the the University of Wisconsin-Madison. J.K.M. received support from The National Library of Medicine grant 5T15LM007359 as well as from NIH training grant T32 GM08349 to the Biotechnology program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. M.A.A. received additional support from NIH training grant T32 GM07226 to the Biological and Biomedical Sciences program at Harvard University, Division of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baer GS, Dermody TS. Mutations in reovirus outer-capsid protein σ3 selected during persistent infections of L cells confer resistance to protease inhibitor E64. J. Virol. 1997;71:4921–4928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4921-4928.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodkin D, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Proteolytic digestion of reovirus in the intestinal lumens of neonatal mice. J. Virol. 1989;63:4676–4681. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4676-4681.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa J, Copps TP, Sargent MD, Long DG, Chapman JD. New intermediate subviral particles in the in vitro uncoating of reovirus virions by chymotrypsin. J. Virol. 1973;11:552–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.11.4.552-564.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa J, Long DG, Sargent MD, Copps TP, Chapman JD. Reovirus transcriptase activation in vitro: involvement of an endogenous uncoating activity in the second stage of the process. Intervirology. 1974;4:171–188. doi: 10.1159/000149856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CM, Chaudhry C, Kim PS. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:14306–14313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein μ1 mediates membrane disruption. J. Virol. 2002;76:9920–9933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9920-9933.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Nibert ML. Protease cleavage of reovirus capsid protein μ1/μ1C is blocked by alkyl sulfate detergents, yielding a new type of infectious subvirion particle. J. Virol. 1998;72:467–475. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.467-475.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Parker JSL, Ehrlich M, Kirchhausen T, Nibert ML. The δ region of outer-capsid protein μ1 undergoes conformational change and release from reovirus particles during cell entry. J. Virol. 2003;77:13361–13375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13361-13375.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Walker SB, Chen Y, Contreras CM, Schiff LA, Baker TS, Nibert ML. In vitro recoating of reovirus cores with baculovirus-expressed outer-capsid proteins μ1 and σ3. J. Virol. 1999;73:3941–3950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3941-3950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Zhang X, Olson NH, Walker SB, Chappell JD, Dermody TS, Baker TS, Nibert ML. Complete in vitro assembly of the reovirus outer capsid produces highly infectious particles suitable for genetic studies of the receptor-binding protein. J. Virol. 2001;75:5335–5342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5335-5342.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CT, Zweerink HJ. Fate of parental reovirus in infected cell. Virology. 1971;46:544–555. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell JD, Barton ES, Smith TH, Baer GS, Duong DT, Nibert ML, Dermody TS. Cleavage susceptibility of reovirus attachment protein σ1 during proteolytic disassembly of virions is determined by a sequence polymorphism in the σ1 neck. J. Virol. 1998;72:8205–8213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8205-8213.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs KM. Stoichiometry of reovirus structural proteins in virus, ISVP, and core particles. Virology. 1998;243:218–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S, Chow M, Hogle JM. The poliovirus 135S particle is infectious. J. Virol. 1996;70:7125–7131. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7125-7131.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien M, Hooper JW, Fields BN. The M2 gene segment is involved in the capacity of reovirus type 3Abney to induce the oily fur syndrome in neonatal mice, a S1 gene segment-associated phenotype. Virology. 2003;305:25–30. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayna D, Fields BN. Genetic studies on the mechanism of chemical and physical inactivation of reovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 1982;63:149–159. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-63-1-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden KA, Wang G, Yeager M, Nibert ML, Coombs KM, Furlong DB, Fields BN, Baker TS. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:1023–1041. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert DH, Deussing J, Peters C, Dermody TS. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24609–24617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong DB, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J. Virol. 1988;62:246–256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden JW, Bahe JA, Lucas WT, Nibert ML, Schiff LA. Cathepsin S supports acid-independent infection by some reoviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8547–8557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JW, Fields BN. Role of the μ1 protein in reovirus stability and capacity to cause chromium release from host cells. J. Virol. 1996;70:459–467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.459-467.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jané-Valbuena J, Nibert ML, Spencer SM, Walker SB, Baker TS, Chen Y, Centonze VE, Schiff LA. Reovirus virion-like particles obtained by recoating infectious subvirion particles with baculovirus-expressed σ3 protein: an approach for analyzing σ3 functions during virus entry. J Virol. 1999;73:2963–2973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2963-2973.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasuriya AK, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Complete nucleotide sequence of the M2 gene segment of reovirus type 3 Dearing and analysis of its protein product μ1. Virology. 1988;163:591–602. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joklik WK. Studies on the effect of chymotrypsin on reovirions. Virology. 1972;49:700–715. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M, Wyss M. Engineering proteins for thermostability: the use of sequence alignments versus rational design and directed evolution. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2001;12:371–375. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liemann S, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, μ1, in a complex with is protector protein, σ3. Cell. 2002;108:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonberg-Holm K, Gosser LB, Shimshick EJ. Interaction of liposomes with subviral particles of poliovirus type 2 and rhinovirus type 2. J. Virol. 1976;19:746–749. doi: 10.1128/jvi.19.2.746-749.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luria SE, Delbrück M. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics. 1943;28:491–511. doi: 10.1093/genetics/28.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AM, Broering TJ, Nibert ML. Mammalian reovirus M3 gene sequences and conservation of coiled-coil motifs near the carboxyl terminus of the μNS protein. Virology. 1999;264:16–24. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JK, Severson TF, Chandran K, Gillian AL, Yin J, Nibert ML. Thermostability of reovirus disassembly intermediates (ISVPs) correlates with genetic, biochemical, and thermodynamic properties of major surface protein μ1. J. Virol. 2002;76:1051–1061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1051-1061.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert ML, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. Infectious subvirion particles of reovirus type 3 Dearing exhibit a loss in infectivity and contain a cleaved σ1 protein. J. Virol. 1995;69:5057–5067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5057-5067.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert ML, Fields BN. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein μ1/μ1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. J. Virol. 1992;66:6408–6418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6408-6418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert ML, Odegard AL, Agosto MA, Chandran K, Schiff LA. Putative autocleavage of reovirus μ1 protein in concert with outer-capsid disassembly and activation for membrane permeabilization. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert ML, Schiff LA, Fields BN. Mammalian reoviruses contain a myristoylated structural protein. J. Virol. 1991;65:1960–1970. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1960-1967.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegard AL, Chandran K, Zhang X, Parker JSL, Baker TS, Nibert ML. Putative autocleavage of outer capsid protein μ1, allowing release of myristoylated peptide μ1N during particle uncoating, is critical for cell entry by reovirus. J. Virol. 2004;78:8732–8745. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8732-8745.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl D, Schmid FX. Some like it hot: the molecular determinants of protein thermostability. Chembiochem. 2002;3:39–44. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020104)3:1<39::AID-CBIC39>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querol E, Perez-Pons JA, Mozo-Villarias A. Analysis of protein conformational characteristics related to thermostability. Protein Eng. 1996;9:265–271. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SC, Schonberg M, Levin DH, Acs G. The reovirus replicative cycle: conservation of parental RNA and protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1970;67:275–281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.1.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturzenbecker LJ, Nibert ML, Furlong DB, Fields BN. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J. Virol. 1987;61:2351–2361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.8.2351-2361.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang SK, Danthi P, Chow M, Hogle JM. Stabilization of poliovirus by capsid-binding antiviral drugs is due to entropic effects. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:335–340. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang SK, McDermott BM, Racaniello VR, Hogle JM. Kinetic analysis of the effect of poliovirus receptor on viral uncoating: the receptor as a catalyst. J. Virol. 2001;75:4984–4989. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.4984-4989.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Burg B, Eijsink VG. Selection of mutations for increased protein stability. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:333–337. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieille C, Zeikus GJ. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001;65:1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.1-43.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgin HW, 4th, Bassel-Duby R, Tyler KL. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing) J. Virol. 1988;62:4594–4604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4594-4604.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin M, Ekstrom M, Garoff H. The fusion-controlling disulfide bond isomerase in retrovirus Env is triggered by protein destabilization. J. Virol. 2005;79:1678–1685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1678-1685.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessner DR, Fields BN. Isolation and genetic characterization of ethanol-resistant reovirus mutants. J. Virol. 1993;67:2442–2447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2442-2447.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetz K, Kucinski T. Influence of different ionic and pH environments on structural alterations of poliovirus and their possible relation to virus uncoating. J. Gen. Virol. 1991;72:2541–2544. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Studies of influenza haemagglutinin-mediated membrane fusion. Virology. 1986;149:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener JR, Joklik WK. Evolution of reovirus genes: a comparison of serotype 1, 2, and 3 M2 genome segments, which encode the major structural capsid protein μ1C. Virology. 1988;163:603–613. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. The reovirus μ1 structural rearrangement that mediates membrane penetration. J. Virol. 2006 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01343-06. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ji Y, Zhang L, Harrison SC, Marinescu DC, Nibert ML, Baker TS. Features of reovirus outer capsid protein μ1 revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction of the virion at 7.0 Å resolution. Structure. 2005;13:1545–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]