Abstract

Lifelong learning for community pharmacists is shifting from continuing education (CE) towards continuing professional development (CPD) in some countries. The objectives of this report were to compare lifelong learning frameworks for community pharmacists in different countries, and determine to what extent the concept of CPD has been implemented. A literature search was conducted as well as an Internet search on the web sites of professional pharmacy associations and authorities in 8 countries. The results of this review show that the concept of CPD has been implemented primarily in countries that have a long tradition in lifelong learning, such as Great Britain. However, most countries have opted for the CE approach, eg, France, or for a combination of CE and CPD, eg, New Zealand. This approach combines the controllability by regulatory organizations that CE requires with the advantage of sustained behavior change seen in successful CPD programs.

Keywords: continuing education, continuing professional development, lifelong learning, community pharmacists

INTRODUCTION

Maintaining competence throughout their careers is a lifelong challenge for all health care professionals. Being aware of the fast evolution of knowledge and the responsibility that health care professionals have should raise concerns about all required competencies. This moral sense, however, has not always sufficiently motivated health care professionals to continuously pursue new knowledge. Consequently, professional associations and authorities alike started developing formal lifelong learning systems with the aim of sustaining the practitioner's competence and ensuring the provision of quality patient care. Traditionally, these systems were based on continuing education (CE) however, in the last few years, there has been a shift towards continuing professional development (CPD). CPD is a process usually conceived as a circle connecting the stages of reflection, planning, action, and evaluation.1 In this process the individual practitioner determines his own learning needs, makes plans to meet those objectives, executes those plans, and finally evaluates whether the actions were successful. These steps are usually recorded in a CPD portfolio. In comparison, CE can be seen as one part of the CPD process, encompassing such traditional teaching methods as lectures, workshops, and distance learning courses. Whereas CPD is focused on the individual practitioner, CE is structured to address the learning needs of the majority of practitioners. One of the reasons for the shift towards CPD is the limited effect of formal CE activities on the behavior of the practitioner.2-5

The CPD approach has started to find acceptance in pharmacy.1,6,7 The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) has adopted the CPD concept in 2002 as the “responsibility of individual pharmacists for systematic maintenance, development and broadening of knowledge, skills and attitudes, to ensure competence as a professional, throughout their careers.”6 While some countries have already fully implemented this concept into their lifelong learning policies, others are still operating a formal CE system, and still others have no official lifelong learning structure at all. Currently, Belgium is in this “no official structure” situation, with pharmacists only having an ethical obligation to regularly take part in CE activities. However, given the importance of lifelong learning in today's society, the increasing number of countries that are developing mandatory systems, and the pressure from the health care system to demonstrate quality of care, Belgian professional associations have started the debate on the implementation of a regulated system, before possibly an externally driven system is enacted. To substantiate this debate, a profound insight into the different systems that are currently used is necessary.

The objectives of this study were to compare lifelong learning frameworks for community pharmacists, and to determine to what extent the CPD concept has been implemented. In this respect, this report could provide a basis for professional associations or authorities that are planning to implement a formal lifelong learning framework. For those countries that already have a system in use, the information provided in this article could inform further developments.

METHODS

The countries selected for this study were the Netherlands, Germany, France, Great Britain, Canada (Ontario), New Zealand, Australia, and the United States. The main reason for choosing these countries was to provide an exemplary description of different approaches to lifelong learning. Other reasons related to access and availability of reliable information in a language with which the researchers were familiar. Moreover, regarding healthcare and education, Belgian policymakers tend to look at neighboring countries such as France, Germany, and the Netherlands in their decision making. The data were collected between September 2005 and June 2006.

For Great Britain and Ontario, Canada, internationally published literature was available on lifelong learning systems for community pharmacists. Literature for the other countries was scarce, so the Internet was searched for relevant information from professional pharmacists' associations and authorities. Additionally, the information from these countries was verified by native experts and/or professional bodies.

Lifelong learning systems were investigated by examining the following organizational features: type of system, voluntary or mandatory nature of the system, presence or absence of rewards, system requirements, type of control, and consequences of noncompliance. The type of system used was defined and evaluated based on the system's requirements. Systems requiring the collection of credit points were defined as CE, whereas systems requiring a portfolio were defined as CPD. Finally, professional education structures other than CE or CPD were defined in accordance with the terminology of the responsible organization. The second feature evaluated, the voluntary or mandatory nature of each program, related to the presence or absence of regulations. A structure was defined as mandatory if compliance was required by law or by registering bodies. A system was defined as voluntary if it allowed pharmacists to participate in CE or CPD without tangible consequences for not complying with recommendations. Rewards were defined as incentives of any kind that were administered in a voluntary or mandatory setting. The item “system requirements” evaluated the nature of the credit points system, the portfolio, and other requirements unique for each system. The item “type of control” indicated to what extent compliance with the system requirements was measured. Finally, “consequences of noncompliance” referred to tangible as well as indirect consequences that occurred as a result of noncompliance with the system requirements or recommendations.

In addition to comparing these organizational features among countries, we searched for unique aspects of each country's system, such as the organizations responsible for the system and the history behind the system.

RESULTS

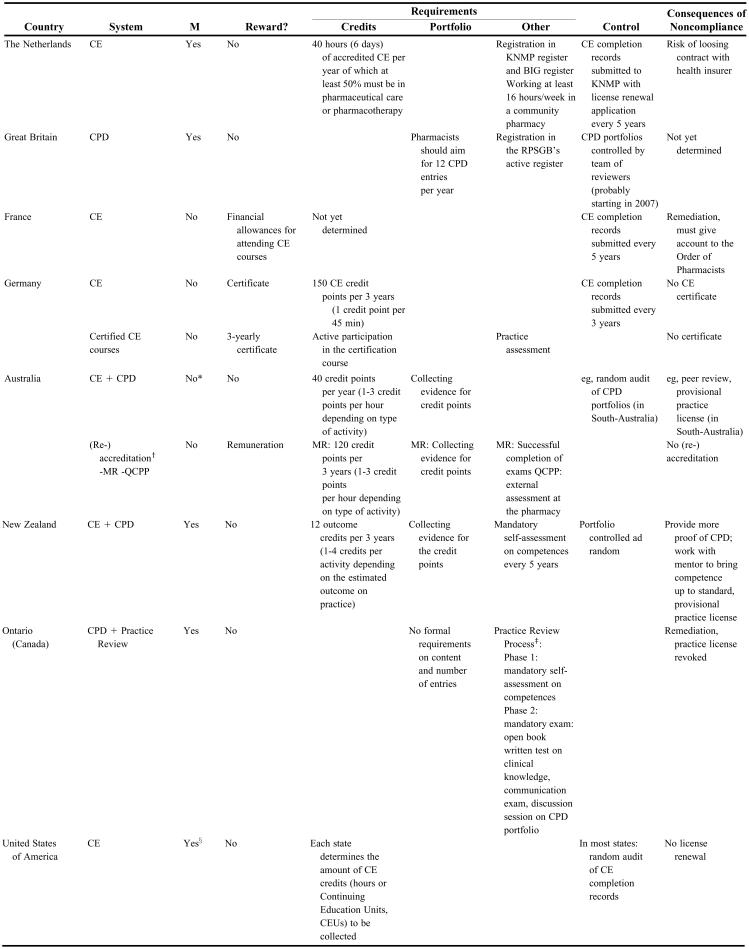

Although each country developed its own system for and regulations of CE and CPD, some commonalities were found. First, irrespective of whether a country's structure is based on CE or CPD, all countries except for Great Britain and the province of Ontario have some variation of a credit points system. This means that pharmacists are required to collect a minimum number of credit points in a defined period of time, usually 3 to 5 years. These credit points are typically a reflection of the time spent on an approved activity. For example, attending a 1-hour lecture results in 1 credit point. However, some countries award more credit points to activities that are more likely to have a substantive impact on practice pattern, such as interactive workshops or activities including assessment. The second common feature relates to the concept of CPD. Systems that are based on CPD tend to have comprehensive competency standards, against which pharmacists have to compare their own level of competence as an integral part of the CPD process.

Finally, the term accreditation is commonly used for both CE and CPD programming, to refer to official approval and recognition of “quality” offerings, albeit that the subject of accreditation varies from country to country. For example, in Germany and the Netherlands, the term accreditation refers to approved CE activities whereas in the United States accreditation refers to approved CE providers. Entire CPD programs can be accredited in New Zealand, whereas in Australia individual pharmacists can be accredited. Table 1 presents the organizational features of lifelong learning systems in each of the countries studied.

Table 1.

Overview of Continuing Education and Continuing Professional Development Programs for Pharmacists in Eight Countries

M = Mandatory; KNMP (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering van de Pharmacie)= Royal Dutch Pharmaceutical Society; BIG (Beroepen Individuele Gezonheidszorg) = Professions related to direct patient care; MR = Medicines Review; QCPP = Quality Care Pharmacy Program

*From 2007, the jurisdictions of Victoria, Australian Capital Territory, South Australia and Tasmania will have mandatory requirements

†After successful completion of the QCPP or MR program, accreditation is obtained. Re-accreditation is the periodically renewal of accreditation

‡In Phase 1, each year 20% of pharmacists active in direct patient care are randomly selected. Of these pharmacists, around 200 are randomly selected for phase 2

§except for the State of Hawaii, beginning with the renewal for the licensing biennium commencing on January 1, 2008

The Netherlands.

Since 1995, the Netherlands have had a system of mandatory CE linked with mandatory registration and re-registration.8 The obligation to pursue CE was gradually introduced over a period of 4 years until, in 1999, the quota of 6 days per year (± 40 hours) was established.9 The lifelong learning system is governed by different organizations. The Royal Dutch Pharmaceutical Society (KNMP), which is the professional association of Dutch pharmacists, manages the registers. A central body sets the criteria for the CE activities. Finally, an accreditation commission evaluates accreditation applications from CE providers and may visit accredited courses unannounced.8,10 The KNMP negotiated the registration and re-registration procedure with the health insurers who agreed to only enter into contracts with KNMP-registered pharmacists. As a result, pharmacists who do not comply with the CE obligation of the KNMP may run the risk of losing their contract with the health insurer. In this way, the KNMP was able to introduce mandatory CE without legal authorization.

The authorities promulgated the “BIG” (Beroepen Individuele Gezondheidszorg) law in 1997.8,11,12 This law constitutes title protection for 8 professions that are related to direct patient care, including that of community pharmacists. Criteria for registration in the BIG-register are related to successful completion of graduate education, whereas criteria for re-registration are related to work experience and CE. However, article eight of this law, which describes this re-registration process, is not yet implemented because of lack of consensus on the criteria for re-registration.13 This means that pharmacists have to be registered in the BIG-register to hold the title of “pharmacist” and in the KNMP-register to be able to conclude a contract with a health insurance fund. The KNMP would like the government to recognize the specialty of “community pharmacist,” so that their register can be merged with the BIG-register and that their criteria for re-registration have legal status.11,13

The debate surrounding a lifelong learning system for pharmacists in the Netherlands continues and further reforms are expected. A critical report of the Dutch Institute for Effective Use of Medication stated that pharmacists should do 60 hours of CE per year instead of 40, more courses on pharmacology and pharmacotherapy should be offered, control should be exercised by means of examinations instead of attendance registration, CE should be competency based in accordance with graduate education, the influence of the pharmaceutical industry on CE should be controlled, and visitation reports of the accreditation commission should be made public.13,14

Great Britain.

Great Britain is one of the pioneers in the adoption of the CPD concept. Because of dissatisfaction with the former system of mandatory CE in which pharmacists had to complete 30 hours of CE per year, a new approach was found in CPD.15,16 Introduced in 1998, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) invited 500 pharmacists to participate in a pilot project to develop CPD within the profession. Through intensive consultation with their members, the system was refined, and in 2002 the first 5000 pharmacists enrolled in the “Plan and Record” CPD framework.17-19 Today, most members of the RPSGB are enrolled and legislation to make enrollment mandatory was expected to be introduced in spring 2007 through the Section 60 Order of the Health Act 1999, rendering pharmacists unable to practice if they don't comply with the mandatory CPD requirements.20,21

Of all studied countries, Great Britain's system is the only one that is fully based on qualitative criteria. Indeed, there are no requirements on the type of CPD activities that participants must report, as long as the activities contribute to the pharmacist' professional development.22 Pharmacists are instructed to aim for 12 CPD entries a year.23 In order to make the system work, a rigorous framework was needed to guide pharmacists in the recording process. Therefore, all pharmacists receive a CPD package, “Plan and Record,” as well as a 30-minute videotape, Introducing CPD. The materials explain that every CPD entry has to be documented in a portfolio (online, through the website of the RPSGB, or on paper) according to the elements of the CPD cycle, including reflection, planning, action, and evaluation. In the reflection part, learning objectives have to be stated, as well as the methods used to identify those objectives and related areas of competence. In the planning field, pharmacists note, among other things, the date by when the learning objectives have to be met as well as the planned activities. The action paragraph reports on the completed activities with the estimated time taken, whereas in the evaluation part, details are provided on the extent to which the learning objectives have been met, examples of application of the learning outcomes, feedback from other persons, etc.22

Such a qualitative system requires qualitative control. When the legislative powers are established, the RPSGB will be able to call in CPD records for review, which will probably happen every 3 to 5 years.23 In the latter part of 2007, the RPSGB will launch a pilot program for reviewing pharmacists' records of their CPD. In cases where poor CPD records are identified, detailed feedback will be provided to the pharmacist on how to improve them, and if that is still insufficient, support may be offered from a RPSGB CPD facilitator.24

France.

In 2002, the legislation necessary to implement mandatory CE in France was passed.25,26 Four years later, in June 2006, the decree that determines the practical applications was issued.27 However, mandatory CE will probably not be implemented before 2008.28 This decree prescribed the formation of a national board for the regulation of CE for pharmacists, as well as the creation of regional boards. The national board will approve CE providers, not individual CE activities, and it will have to decide on mandatory CE topics and the number of CE courses that have to be completed. From the moment the regional boards are established, CE becomes mandatory. Pharmacists will have to submit their CE records to these boards every 5 years. In case of noncompliance, a plan will be discussed for fulfilling the CE requirements. If the pharmacist is not willing to cooperate, the Ordre des Pharmaciens (Order of Pharmacists) will be informed and they will decide upon disciplinary sanctions.

Of all the countries studied, France has the most developed CE system in terms of legal rights and financial arrangements.29-31 These rights and arrangements are regulated by 3 different systems: the Droit Individuel à la Formation (DIF; Individual Right to Education), the Congé Individuel de Formation (CIF; Educational Leave), and the Plan de Formation (PF; Educational Plan). According to DIF, full-time employees have the right to 20 hours of CE each year. Employees must take the initiative and ask for written agreement from their employers to complete the CE. Normally, the CE activities take place outside of working hours and the employee receives from the employer an allowance equal to 50% of his/her real income. If the CE activities take place during working hours, the entire salary of the employee is maintained.32 The CIF enables employees to spend up to 1 year (maximum of 1200 hours) pursuing an educational activity of their choice (not necessarily related to their profession). The employer cannot refuse. During this leave, the employment contract is temporarily terminated and the employee is paid by the Fonds de gestion du congé individuel de formation (FONGECIF; fund for the operation of the CIF).33 Finally, the PF framework covers every CE activity initiated by the employer. These CE activities normally take place during working hours, but may take place outside working hours (maximum of 80 hours per year per employee). Funds such as the FIF-PL (Fonds Interprofessionnel des Professionnels Libéraux) for pharmacy owners, and the OPCA-PL (Organisme Paritaire Collecteur Agrée des Professions Libérales) for pharmacy staff, guarantee financial compensation for taking part in CE.

Germany.

Germany introduced a voluntary CE certification system for pharmacists in response to pressure for pharmacists to prove quality and to defend the self-regulated status of the profession.34,35 This certification system was implemented State Chamber by State Chamber from 2001 to 2006, with each State adapting the Federal Chamber's recommendations to their own specific regulations. The certificate can be earned every 3 years if the requirement of 150 credit points per 3 years is fulfilled. In general, 1 credit point is awarded for every 45 minutes of CE that is completed, and an extra point is allocated if an assessment is successfully completed. The accreditation applications are evaluated by the Bundesapothekerkammer (Federal Chamber of Pharmacists) and the different Landesapothekerkammern (State Chamber of Pharmacists) for activities organized on national or regional level, respectively. In addition to the voluntary certification system, pharmacists can enroll in specific certified CE courses such as Pharmaceutical Care for Patients With Diabetes.36,37 These courses require active participation as well as successful completion of a practice assessment to earn the certificate. Usually, these certified courses can also count as credit points toward the 3-yearly CE certificate.37

Australia.

Australia has 2 systems: a re-registration system, which includes a commitment to lifelong learning, and voluntary accreditation programs with remuneration. By 2007, 4 of the country's 8 jurisdictions will require pharmacists to demonstrate or show proof of their involvement in lifelong learning activities. Although each jurisdiction determines how this lifelong learning requirement has to be demonstrated, the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) designed a recommended framework for the recording of CPD. This framework is based on a weighted credit points system, allocating greater value to more effective educational activities.38 In addition, the PSA as well as other professional bodies provide activities suitable for incorporation into the CPD programs of the member states.

Apart from this CPD system, pharmacists negotiated a remunerated accreditation system with the Government. Two accreditation programs are available: the Quality Care Pharmacy Program (QCPP), for which the Australian Government has recognized the Pharmacy Guild; and the Medicines Review (MR) program, for which the Australian Government has recognized the Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy (AACP) and the Society of Hospital Pharmacists (SHPA).39-41 QCPP is a program focused on raising the standard of customer service in individual pharmacies and is based on business and professional standards. Thus, accreditation in QCPP involves the whole pharmacy. In contrast, the MR program is completed by individual pharmacists. Both programs require a form of assessment to obtain accreditation and re-accreditation. In the case of MR, the reward consists of a fee per review, and the permission to use the postnominals AACPA (AACP accredited). Accredited QCPP pharmacies are eligible to receive an incentive payment, get access to remuneration for services where QCPP accreditation is a prerequisite, and use the QCPP logo.40

New Zealand.

New Zealand introduced the concept of CPD in 2001, with a voluntary pilot program that ran for 4 years. The program requirements were finalized in 2005 and made available to all New Zealand registered pharmacists, although still on a voluntary basis. CPD became mandatory in April 2006. Currently, New Zealand's Pharmacy Council has only accredited the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand's (PSNZ's) “ENHANCE” CPD program. This system is unique in that it is not based on a traditional credit points system. Instead, the PSNZ developed an outcome credits system in which pharmacists allocate credits for a CPD activity based on the outcome it had on their practice. Accordingly, 3 scales were developed together with guidelines to assist pharmacists in allocating the appropriate number of credits to their CPD activities. Upon request, evidence to support the outcomes of their CPD has to be submitted.42 Apart from the CPD requirements, pharmacists also have to complete a self-assessment on competences every 5 years, unless they change their area of practice, in which case, another self-assessment against the Competence Standards must be taken.

Canada (Ontario).

Ontario has a mandatory Quality Assurance Program consisting of a two-part registration system, a learning portfolio, and a practice review process with remediation. The function of the register is to distinguish between pharmacists active in direct patient care (part A) and those active in non-direct patient care (part B). Regardless of their registration part, all pharmacists have to keep a learning portfolio to demonstrate lifelong learning. Pharmacists from part A of the register are obliged to take part in the Practice Review Process when selected. Phase one of this process includes sending in a summary of completed CE activities that have been undertaken as part of the CPD process, and the completion of a self-assessment survey, which assesses pharmacists' own learning needs. Each year, 20% of pharmacists are randomly selected for phase 1 of this program so that every pharmacist goes through the process once every 5 years. Phase 2 of the Practice Review Program involves a direct assessment consisting of 3 activities: a 115-minute open-book written test of clinical knowledge (multiple-choice questions), five 12-minute standardized-patient interview scenarios reflecting contemporary practice, and a 60-minute educational session on CPD and the portfolio. Because of this mandatory assessment component, there are no quantitative criteria for the content of the CPD portfolio. Each year, about 200 pharmacists from the phase 1 pool are randomly selected to take part in phase 2. In 2001, the first 5-year cycle of the Practice Review Program was completed. Of the 992 pharmacists who had participated in the phase 2 process, 86% received satisfactory scores on the test, while 14% did not and received remedial assistance from a colleague.43-47 Most of the pharmacists from the peer assistance group successfully completed a reassessment within 1 year.

United States.

In 1965, the state of Florida was the first to implement mandatory CE for pharmacists.48 Today, all 50 states except for Hawaii, require pharmacists to participate in accredited or approved CE.49 The requirement is based on number of hours of participation and the average requirement is 30 hours every 2 years. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) sets accreditation standards and accredits CE providers, rather than individual CE activities.50 Some states require a minimum number of credits to be gathered from live courses (eg, Florida), while others require a minimum number of ACPE-accredited courses (eg, Indiana), or specify specific topics for which credit points have to be collected (eg, in Arizona, every 2 years pharmacists should have followed at least 3 hours on pharmacy law). Recent concerns about the effectiveness of traditional CE have been a source of much debate, and the CPD model has been discussed as a means of improving the quality of the existing system of CE in order to support maintenance and enhancement of the competencies required to deliver pharmacy services in an increasingly patient-oriented environment.48

DISCUSSION

CE has proven to be an insufficient method of changing pharmacists' behavior.2,5 Despite this, some of the countries that are just starting to implement a formal lifelong learning system still choose the CE approach (eg, Germany). The reasons for this differ. First, a system that strictly follows the principles of CPD, such as the system in Great Britain, requires substantial support and is time consuming. Second, when choosing a CPD system, a framework has to be developed that enables pharmacists to satisfy their personal learning needs and is based on the CPD stages of reflection, planning, action, and evaluation. This framework may also include comprehensive competency standards against which pharmacists can assess their own level of competence as a part of the reflection stage of the CPD cycle. Moreover, pharmacists will probably need a good understanding of what CPD is, how they are supposed to document it, and how their records will be evaluated before they pursue CPD. On the other hand, the advantage of a system based on CE is that it allows quantitative evaluation, which many pharmacists value.46,51 Also, in terms of regulatory bodies evaluation of credits may be more straightforward than evaluation of CPD portfolios. This may also explain why some countries combine elements of CE (eg, credit points system) and CPD (eg, portfolio).

Together with the debate on CE versus CPD, the question of mandatory versus voluntary systems arises. Often, this question is beyond the authority of pharmacists' regulating regulatory bodies. However, irrespective of its voluntary or mandatory nature, every system should aim to motivate pharmacists to engage in lifelong learning. One strategy to increase motivation is to maximize pharmacists' autonomy and freedom, even in mandatory settings.52 In the traditional mandatory CE approach, there is not much room for freedom. Except for providing a range of activities from which pharmacists can select, the number of credits that must be earned is fixed. In contrast, the CPD approach gives pharmacists more freedom and choices. This is demonstrated by the “Plan and Record” CPD system of Great Britain. This system moves away from a CE credits approach towards a framework in which pharmacists have full responsibility for their portfolio. Another example is the ENHANCE CPD system in New Zealand in which pharmacists themselves determine the outcomes of their CPD activities. Such systems that create supportive conditions for harnessing the autonomous development of pharmacists and in which pharmacists have a sense of volition and the experience of choice, have been proven to facilitate tasks that require disciplined engagement such as CE and CPD.52,53 This approach of giving more responsibility to the pharmacists themselves could be a facilitator for the integration of mandatory lifelong learning policies, which in turn could result in more sustained behavior change. This means that the CPD approach could indeed be more effective than the CE approach. However, because of the recent implementation of CPD models, this still needs to be investigated.

There is no single approach to lifelong learning systems for pharmacists. Each country's lifelong learning system has developed incrementally over time and reflects domestic institutional constraints. This also means that a system could not be transferred from one country to another without first adapting it to local circumstances. For example in Belgium, we think it would be difficult to implement the mandatory CPD system of Great Britain, in which pharmacists do not receive financial rewards for engaging in CPD. In Belgium, doctors have a CE system in which they are financially rewarded.54 Belgian doctors who comply with the CE requirements (approximately 20 hours per year) can become accredited, and gain the right to a higher honorarium per patient and an agreed accreditation fee per year.55 Rejecting such a reward system for pharmacists would probably result in a “if they can, why can't we?” attitude. This does not mean that a reward structure is not desirable, but it indicates the influence of the environment.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite a general awareness that the CE approach is not sufficient for changing the behavior of pharmacists, the shift towards CPD has not yet made much headway in the countries studied. The complexity of CPD, as well as each country's traditions, experiences, and environmental influences make it difficult to implement the CPD approach. Therefore, although some countries have adopted the philosophy of CPD, they continue to use typical CE elements such as the credits system. These mixed systems appear to offer controllability by regulatory organizations, which is inherent to CE, as well as a framework for pharmacists that enables sustained behavior change, which is inherent to CPD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank IPSA for the PhD grant, and Jan de Smidt (KNMP, the Netherlands); Jeff Hughes (Australia); Guy Kretschmer (COPRA, Australia), Peter Halstead (PBSA, Australia); Elisabeth Johnstone (PSNZ, New Zealand); Marcus Droege (United States), Mike Rouse (ACPE, United States); l'Ordre des Pharmaciens (France); Christian Elsen (Belgium); and Christiane Staiger (Germany) for their contributions to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rouse MJ. Continuing professional development in pharmacy. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61:2069–76. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.19.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis D, Thomson MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education. Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior of health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282:867–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis D, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274:700–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.9.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis D, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;157:408–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson MA, Freemantle N, Oxman AD, Wolf FM, Davis D, Herrin J. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030. 2DOI: CD003030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Pharmaceutical Federation. Statement of professional standards. Continuing professional development. Available at: http://www.fip.org/pdf/CPDStatement.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2005.

- 7. American Pharmacists Association. Continuing professional development for pharmacists. APhA policy paper. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association 2004. Available at: www.aphanet.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=3001. Accessed December 21, 2005.

- 8.Rendering JA, de Smidt J. Ter waarborging van de kwaliteit; de registratiefase voor openbaar apothekers. [Quality assurance; registration for community pharmacists] Pharm Week. 2001;136:347–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Smidt J. Vijftig cursusdagen in vier jaar [Fifty course days in four years] Pharm Week. 1999;133:926–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rendering JA. Teugels voor accreditatie worden aangehaald [Reins for accreditation drawn in] Pharm Week. 2003;138:1557. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss F, de Smidt J, Stoffelsen B. BIG-registratie apothekers gaat van start [BIG registration for pharmacists has started] Pharm Week. 1997;132:1286–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vugts CJ, Hingstman L Herregistratie in het BIG-register: een eerste inventarisatie. [Re-registration in the BIG register: a first inventory]. Utrecht: Nivel; 2004. Available at: www.nivel.nl/pdf/Herregistratie-in-het-BIG-register.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2005.

- 13. van Rijn van Alkemade EM. Beleidssignalement nascholing farmacotherapie. [Policy statement on continuing education in pharmacotherapy. Dutch Institute for the Proper Use of Medicine] Utrecht: Nederlands Instituut voor Verantwoord Medicijngebruik; 2005. Available at: http://www.dgvinfo.nl/downloads/Signalement_nascholing_farmacotherapie_20050407.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2005.

- 14.DGV baseert zich op onjuiste feiten [editorial] [Dutch Institute for the Proper Use of Medicine relies on improper facts] Pharm Weekblad. 2005;140:519. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhan F. A review of pharmacy continuing professional development. Pharm J. 2001;267:613–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hancox D. Making the move from continuing education to continuing professional development. Pharm J. 2002;268:26–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkin B. Pharmacy in a new age (PIANA): the road to the future. Tomorrow's Pharmacist. 1999:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hull H, Rutter P. A cross sectional survey of UK community pharmacists' views on continuing education and continuing professional development. Int J Pharm Educ. 2003;2:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Survey result: Mandatory CPD welcomed. Pharm J. 2003;270:456–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Council orders review of long-term implications of CPD programme. Pharm J. 2005;274:771. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Section 60 Order: what's it all about?[insert] Pharm J. 2006;276.

- 22. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Plan and Record. Available at: www.uptodate.org.uk/PlanandRecord/PlanandRecord_TextV1.1.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2005.

- 23. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. CPD requirements and mandatory CPD: Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: http://www.uptodate.org.uk/faqs/requirements.shtml. Accessed February 17, 2006.

- 24. The Pharmaceutical Society of great Britain. Pharm J. 2007;278(7442);291.

- 25. Loi n° 2002-303 du 4 mars 2002 relative aux droits des malades et à la qualité du système de santé. [Law number 2002-303 of March 4, 2002 on the rights of patients and the quality of the health care system]. Available at: http://www.legifrance.fr. Accessed June 6, 2006.

- 26. Loi de F. Fillon du 4 mai 2004 relative à la formation professionnelle tout au long de la vie et au dialogue social [Law of F. Fillon of May 4, 2004 on lifelong professional development and the social dialogue]. Available at: http://admi.net/jo/20040505/SOCX0300159L.html. Accessed June 6, 2006.

- 27. Décret no 2006-651 du 2 juin 2006 relatif à la formation pharmaceutique continue [Decree No. 2006-651 of June 2, 2006 concerning continuing pharmaceutical education]. Available at: http://www.moniteurpharmacies.com/infos/joe_20060603_0128_0030.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2006.

- 28. Micas C Formation continue: pourquoi ça coince? [Continuing education: why are we not moving on?]. Le Quotidien; May 14, 2007. Available at: http://www.quotipharm.com/journal/index.cfm?fuseaction=viewarticle&DArtIdx=390716 Accessed: May 17, 2007.

- 29. Fonds Interprofessionnel de Formation pour les Professions Libéraux. Critères 2004 pour pharmaciens. [Criteria 2004 for pharmacists]. Available at: http://www.fifpl.fr/gestionnaf/criteres/professions/523.htm. Accessed June 6, 2006.

- 30. Organisme Paritaire Collecteur Agrée pour les Professions Libéraux. Pharmacies d'officine. [Community pharmacies]. Available at: http://www.opcapl.com/index.cfm. Accessed June 6, 2006.

- 31. Ordre des Pharmaciens. Les formations initiales et permanentes. [Graduate and continuing education]. Available at: http://www.ordre.pharmacien.fr. Accessed June 6, 2006.

- 32. Droit Individuel à la Formation [Individual Right to Education]. Available at: http://vosdroits.service-public.fr/particuliers/F10705.xhtml. Accessed June 14, 2006.

- 33. Congé Individuel de Formation [Educational Leave]. Service-Public.fr (le portail de l'administration française)Available at: http://vosdroits.service-public.fr/particuliers/F3024.xhtml. Accessed June 14, 2006.

- 34. Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. Leitsätze zur apothekerlichen Fortbildung - Empfehlungen der Bundesapothekerkammer [Guiding principles for pharmacy continuing education - Recommendations of the federal pharmacists chamber]. Available at: http://www.abda.de. Accessed January 3, 2006.

- 35. Hollstein P. Ohne fortbildung geht gar nichts. [Without continuing education nothing will work]. Pharmazeutische Zeitung [serial online]. 2005; issue 25.

- 36. Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. Zertifikatfortbildung. [Certified continuing education courses]. Available at: http://www.abda.de. Accessed April 14, 2006.

- 37. Staiger C. Paradigmenwechsel in der Fortbildung. [Paradigm shift in continuing education]. Pharmazeutische Zeitung [serial online]. 2005; issue 48.

- 38. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. CPD & PI program. Available at: http://www.psa.org.au/ecms.cfm?id=396. Accessed January 11, 2006.

- 39. Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy. The facts on accreditation and remuneration for medication reviews. Available at: http://www.aacp.com.au. Accessed November 23, 2005.

- 40. Pharmacy Guild. About the Quality Care Pharmacy Program. Available at: http://beta.guild.org.au/qcpp/. Accessed June 22, 2006.

- 41. The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia. Continuing Professional Development Program. Available at: http://www.shpa.org.au/docs/cpd.html. Accessed October 6, 2006.

- 42. Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand. ENHANCE. Available at: http://www.psnz.org.nz/public/enhance/what_is_enhance/Enhance.aspx. Accessed November 23, 2005.

- 43.Des Roches B. Professional Profile and learning portfolio: thoughts and tips. Pharm Connection. 2002;(SeptOct):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Austin Z, Croteau D, Marini A, Violato C. Continuous professional development: the Ontario experience in professional self-regulation through quality assurance and peer review. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67 Article 56. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Austin Z, Marini A, Croteau D, Violato C. Assessment of pharmacists' patient care competencies: validity evidence from Ontario (Canada)'s Quality Assurance and Peer Review Process. Pharm Educ. 2004;4(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Austin Z, Marini A, MacLeod Glover N, Croteau D. Continuous professional development: a qualitative study of pharmacists' attitudes, behaviors, and preferences in Ontario, Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69 Article 4. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ontario College of Pharmacists. Quality Assurance Program: Policy Guide. Ontario College of Pharmacists; 2001. Available at: http://www.ocpinfo.com. Accessed September 2, 2005.

- 48. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy Continuing professional development in pharmacy. Washington, DC; 2004. Available at: http://www.pharmacycredentialing.org. Accessed September 2, 2005.

- 49. Medscape. State CE requirements for pharmacists. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/pages/cme/pharmcestatereqirements. Accessed April 10, 2006.

- 50. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and criteria. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/ceproviders/standards.asp. Accessed April 10, 2006.

- 51.Mottram DR, Rowe P, Gangani N, Al-Khamis Y. Pharmacists' engagement in continuing education and attitudes towards continuing professional development. Pharm J. 2002;269:618–22. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryan R, Deci E. Overview of self-determination theory: an organismic dialectical perspective. In: Deci E, Ryan R, editors. Handbook of Self-determination Research. Rochester: University of Rochester Press; 2002. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gagné M, Deci E. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organ Behav. 2005;26:331–62. DOI: 10.1002/job.322. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peck C, McCall M, McLaren B, Rotem T. Continuing medical education and continuing professional development: international comparisons. BMJ. 2000;320:432–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7232.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. RIZIV. Voorwaarden waaraan een geneesheer moet voldoen om geaccrediteerd te worden en te blijven. [Physicians' conditions of accreditation]. Available at: http://inami.fgov.be/care/nl/doctors/accreditation/individual-accreditation/conditions-accreditation.htm. Accessed June 22, 2006.