Abstract

In recent work, we described the excision of a large genomic region from Enterococcus faecium D344R in which the sequence from “joint” regions suggested that excision resulted from the interaction of conjugative transposon Tn916 and the related mobile element Tn5386. In the present study, we examined the ability of integrases and integrase-excisase combinations from Tn916 and Tn5386 to promote the excision of constructs consisting of the termini of Tn916, Tn5386, and the VanB mobile element Tn5382. Integrases alone from either Tn916 or Tn5386 promoted the circularization of constructs from the three different transposons, even when the different termini used in the constructs were discordant in their transposon of origin. The termini of Tn916 and Tn5382 found in all joints were consistent with previously identified Tn916 and Tn5382 termini. Substantial variation was seen in the integrase terminus of Tn5386 used to form joints, regardless of the integrase that was responsible for circularization. Variability was observed in joints formed from Tn5386 constructs, in contrast to joints observed with the termini of Tn916 or Tn5382. The coexpression of excisase yielded some variability in the joint regions observed. These data confirm that integrases from some Tn916-like elements can promote circularization with termini derived from heterologous transposons and, as such, could promote excision of large genomic regions flanked by such elements. These findings also raise interesting questions about the sequence specificities of the C terminals of Tn916-like integrases, which bind to the ends and facilitate strand exchange.

Transposition of prototype conjugative transposon Tn916 occurs by a conservative mechanism in which the first step is excision of the element to form a circular intermediate (1). Within this circular intermediate, the “joint” between the two ends is composed of a heteroduplex consisting of six base strands reflecting the “junction” sequences flanking the ends of the element at its previous integration site (11). There is evidence to suggest that, in Enterococcus faecalis at least, this heteroduplex is resolved in vivo (7). Excision results from the action of the transposon-encoded integrase (Int-Tn) (8). Depending on the conditions under which assays are run, transposon-encoded excisase (Xis-Tn) may also be required (4, 8). Int-Tn is a member of the lambda integrase family of tyrosine recombinases. Its N terminus has been shown by DNase protection assays (6) and liquid nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies (14) to bind to regions within the ends of the transposon that are composed of 12-bp imperfect direct repeats (DR2). The C-terminal of the integrase binds to the transposon ends and flanking sequences, facilitating strand breakage and exchange (6). In the absence of any observations to the contrary, Tn916 integrase has been presumed to interact specifically with Tn916 termini.

We recently characterized the excision of a large segment of the genome from E. faecium D344R (9). The 170-kb segment was flanked by a copy of Tn916 and a novel Tn916-like transposon designated Tn5386. Tn5386 contained genes homologous to the Tn916 integrase (66% amino acid identity and 81% similarity over the span of the enzyme) and excisase (83% identical and 91% similar over 67 amino acids), and regions of direct repeat within its ends were similar to Tn916's (9). However, the termini of Tn5386 and Tn916 are different. The excised segment of the D344R genome extended from the “outside” terminus of Tn916 to the “inside” terminus of Tn5386. Analysis of joint regions of the excised segments suggested that the excision resulted from interaction between the ends of the two transposons, with evidence to suggest that the Tn916 integrase was at least in some instances responsible for excision (9). In the present study, our aims were to test the ability of the Tn916 integrase to mediate circularization of the integrated ends of Tn5386 and the ability of the Tn5386 integrase to mediate circularization of the integrated ends of Tn916. We also determined whether either of these two integrases could promote circularization of the integrated ends of the vancomycin resistance transposon Tn5382. Finally, we determined whether the presence of the associated excisase had an impact on the content of joints resulting from excision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains used in these experiments are described in Table 1. E. faecium D344R is a clinical isolate originally recovered in France (9). The plasmids described in Table 1 were used in the final excision experiments (all intermediate plasmids in the construction of these final plasmids are not included).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Resistance phenotype or genotype or cloning vectora | Description (source) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. faecium | ||

| D344R | Apr Eryr Tcr | Ampicillin-resistant clinical isolate (9) |

| C68 | Apr Eryr Gmr Tcr Vmr | Clinical isolate; source for amplification of termini and flanking sequences of Tn5382 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH10B | ΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK ΔrpsL endA1 nupG | Transformation-competent E. coli (Invitrogen) |

| BL21(DE3) | E. coli B F−dcm ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) gal λ(DE3) | Strain used to express Tn916 or Tn5386 integrase or excisase-integrase behind T7lac promoter in pCDF-1b (Novagen) |

| CJ236(NEB) | FΔ(HindIII)::cat (Tra+ Pil+ Camr)/ung-1 relA1 dut-1 thi-1 spoT1 mcrA | Strain used for cloning dUTP-containing PCR product into PCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen) |

| EPI300 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK λ−rpsL nupG trfA dhfr | Strain used for maintaining copy control of pCC1 plasmids (Epicenter Biotechnologies) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Apr | Cloning vector |

| pCR-XL-TOPO | Kmr | E. coli vector for cloning PCR products directly (Invitrogen) |

| pCC1(Blunt) | Cmr | E. coli F-factor replicon (maintains one copy per cell) with an inducible high-copy oriV origin of replication (Epicenter Biotechnologies) |

| pCDF-1b | Smr Spr | Replicon from CloDF13 for protein expression (Novagen) |

| pACYC184 | Cmr Tcr | Cloning vector (10) |

| pCWR1324 | pCC1(blunt) | PCR product containing the integrase gene from Tn916 |

| pCWR1122 | pCC1(blunt) | PCR product containing the integrase gene from Tn5386 |

| pCWR1121 | pCDF-1b | Inducible expression of Tn5386 integrase |

| pCWR1323 | pCDF-1b | Inducible expression of Tn5386 integrase and excisase |

| pCWR1326 | pCDF-1b | Inducible expression of Tn916 integrase |

| pCWR1327 | pCDF-1b | Inducible expression of Tn916 integrase and excisase |

| pCWR1109 | pACYC184 | bp 1 end and integrase end of Tn5386 |

| pCWR1110 | pACYC184 | bp 1 end and integrase end of Tn916 |

| pCWR1176 | pACYC184 | bp 1 end and integrase end of Tn5382 |

| pCWR1126 | pACYC184 | bp 1 end of Tn916 and integrase end of Tn5386 |

| pCWR1127 | pACYC184 | bp 1 end of Tn5386 and integrase end of Tn916 |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Eryr, erythromycin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Spr, spectinomycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance. Cloning vectors are specified for plasmids.

Genetic techniques.

Isolation of genomic DNA was performed as previously described (2). Isolation of plasmid DNA was performed by using a Promega plasmid extraction kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Restriction digestion, ligation and transformation of Escherichia coli DH10B cells was performed as previously described (2). All sequencing was performed by Cleveland Genomics (Cleveland, OH).

Construction of plasmids for use in excision experiments.

These experiments required the construction of plasmids in which the ends of each of the three different transposons ligated into a plasmid vector (pACYC184) coresided in E. coli with the integrase or excisase-integrase genes from Tn916 or Tn5386 ligated to pCDF-1b (Novagen, Madison, WI) downstream of an IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible promoter. The vectors used in developing the constructs and the final plasmids are listed in Table 1. The general structures of the final plasmids are detailed in Fig. 1. The primers used in making the constructs are listed in Table 2. For cloning the integrase or excisase-integrase genes from Tn916 and Tn5386, oligonucleotides were synthesized to PCR amplify the region extending from just upstream of the excisase or integrase ribosome-binding site to the region downstream of the predicted stop codon of the integrase open reading frame (ORF). Amplification products were produced by using Pfu polymerase for a minimum number of cycles (n = 20), ligated to Copy Control pCC1 (Blunt Cloning Ready) and inserted by electroporation into E. coli EPI300 (Epicenter Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) to maintain copy control. The inserts were then removed by digestion with NcoI and BamHI and directionally cloned into pCDF-1b, yielding pCWR1121 (Tn5386 integrase ORF), pCWR1323 (Tn5386 excisase and integrase ORFs), pCWR1326 (Tn916 integrase ORF), and pCWR1327 (Tn916 excisase and integrase ORFs).

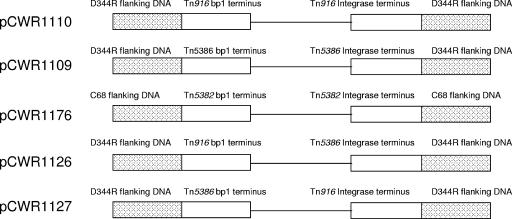

FIG. 1.

Graphical demonstration of the content of the inserts in the five plasmids used to test for excision.

TABLE 2.

Primers used to generate PCR products for use in excision experiments

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5382int | CCTAGAAGTCGACGGTTAGCCAATGCGGGAATGAAC | Tn5382 integrase end and downstream flanking region |

| Tn5382int flank | CCTAGTCGGATCCGTTCATTGATGGTCGGTGC | PCR product |

| Tn5382 bp1 | CCTAGAAGTCGACGGTATTAGCAGTATGGTTCAGC | Tn5382 upstream flanking region and bp 1 region PCR |

| Tn5382bp1 flank | CCTAGTCAAGCTTGTGGCGTTATCGTCACAGTC | product |

| Tn916int | CCTAGAAGTCGACGTCTTGTTGCTTAGTAGTAC | Tn916 integrase end and downstream flanking region |

| Tn916int flank | CCTAGTCGGATCCTATGGGAGATGATACTGTGGTCAC | PCR product |

| Tn916 bp1 | CCTAGAAGTCGACTTCACTTTTCAAGGATAAATCG | Tn916 upstream flanking region and bp 1 region PCR |

| Tn916 bp1 flank | CCTAGTCAAGCTTGTTGGATGTCAATTGATAGTACTAG | product |

| Tn5386int | CCTAGAAGTCGACGCTCACGGCTCATTTGGTTCTGC | Tn5386 integrase end and downstream flanking region |

| Tn5386int flank | CCTAGTCGGATCCTGTACCGACGATTACTACTTTACGAC | PCR product |

| Tn5386 bp1 | CCTAGAAGTCGACTGATGTGCTGTATTCATAAC | Tn5386 upstream flanking region and bp 1 region PCR |

| Tn5386 bp1 flank | CCTAGTCAAGCTTTTAGGTGCGATTGCTGTC | product |

| Upstream intTn5386 | CCAAGTCTAGCCATGGAATATTTATATGACGTATCTAGGCTTGC | Primer for amplifying the Tn5386 int gene; used with StopintTn5386 |

| Stop intTn5386 | CCAAGTCTATGGATCCGTATTTACTACAACGCACATATCC | Primer for amplifying the Tn5386 int gene; used with UpstreamintTn5386 |

| Upstream intTn916 | CCAAGTCTAGCCATGGTTATAGATACATTGGACGCAATCTAG | Primer for amplifying the Tn916 int gene; used with StopintTn916 |

| Stop intTn916 | CCAAGTCTATGGATCCATTTGTACTACTAAGCAACAAGACGCTCCTG | Primer for amplifying the Tn916 int gene; used with UpstreamintTn916 |

| Tn5386Xis up | CAAGTCTAGCCATGGTTCTGCCCACAAGAATGG | Primer for amplifying the Tn5386 xis and int genes; used with StopintTn5386 |

| Tn916Xis up | CCAAGTCTAGCCATGGTGGAACTCCCGTGAGCTTTG | Primer for amplifying the Tn916 xis and int genes; used with StopintTn916 |

| Tn5382-1 | TACCGACATTCAAGAACTTCTAAAAAGATAATC | Used to detect circularization of Tn5382 construct |

| Tn5382-2 | TTGGTAGTAAATTGAGTTCTCATATCCTGC | Used to detect circularization of Tn5382 construct |

| Tn916-1 | GTTTTGACCTTGATAAAGTGTGATAAGTCC | Used to detect circularization of Tn916 construct |

| Tn916-17890 | CACTTCTGACAGCTAAGACATGAG | Used to detect circularization of Tn916 construct |

| Tn5386-1 | TGAACCCTTATAAAAGCGAATACAGCTAGG | Used to detect circularization of Tn5386 construct |

| Tn5386-2 | GCTAAACTGACATTTAAGAAGTTATGAAGAGATAAGTGG | Used to detect circularization of Tn5386 construct |

| pACYC Cm-1 | GATTGGCTGAGACGAAAAACATATTCTC | Used for quantitative PCR to equalize plasmid quantities in plasmid preparations for excision amplifications |

| pACYC Cm-2 | TATGGGATAGTGTTCACCCTTGTTACAC | Used for quantitative PCR to equalize plasmid quantities in plasmid preparations for excision amplifications |

PCR amplification of flanking regions and ends of the transposons used Promega 2× PCR Master Mix according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Most previous articles describe Tn916 as having “left” and “right” ends. However, a 2005 amendment to the Tn916 sequence in the GenBank (accession no. NC_006372) resulted in an inversion of the numbering of the transposon. To avoid confusion with these designations, we refer to the termini as the “bp 1” (in the present GenBank sequence) and “integrase” termini. Oligonucleotides were designed for the bp 1 flanking sequence with inclusion of a HindIII restriction site and within the transposon near the bp 1 end with a SalI restriction site. Flanking oligonucleotides for the integrase end were designed with a BamHI restriction site, and the oligonucleotides located between the integrase and direct repeat within the transposons were designed with inclusion of a SalI site. These PCR amplification products were ligated to pCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into E. coli DH10B (Invitrogen) electroporation-competent cells. The BamHI/SalI fragment containing the integrase end was first ligated into like-digested pUC18. This plasmid was then digested with HindIII/SalI to accommodate the HindIII/SalI fragment containing the bp 1 end. The total insert was removed by digestion with BamHI/HindIII, ligated to BamHI/HindIII-digested pACYC184, and introduced into E. coli DH10B by electroporation. Five plasmid constructs resulted from these efforts (Fig. 1). The insert in pCWR1109 contained the two ends of Tn5386, along with flanking sequences from the insertion site in E. faecium D344R. The insert in pCWR1110 contained the ends of Tn916, along with flanking sequences from the insertion site in E. faecium D344R. The insert in pCWR1176 contained the ends of Tn5382, along with flanking sequences from the insertion site in E. faecium C68. The insert in pCWR1126 contained the bp 1 end of Tn916 and its flanking sequence paired with the integrase end of Tn5386 and its flanking sequence; the insert in pCWR1127 contained the bp 1 end of Tn5386 and its flanking sequence and the integrase end of Tn916 with its flanking sequence. All of the plasmid constructs were then transformed by electroporation into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing either pCDF-1b, pCWR1121 (Tn5386 integrase), pCWR1323 (Tn5386 excisase and integrase), pCWR1326 (Tn916 integrase), or pCWR1327 (Tn916 excisase and integrase). The lengths of the different PCR products used to create the plasmid constructs are shown in Fig. 2.

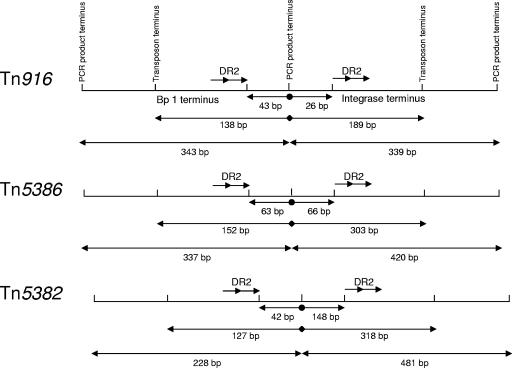

FIG. 2.

Graphic depiction of the distances between important landmarks in making the transposon constructs. The different drawings are not done to scale. The numbers underneath the arrows represent the number of base pairs between the landmarks. The central point represents the end of the primer used to generate PCR products from within the different transposons. The distance between this point and the DR2 integrase binding sites is marked by the arrows terminating in solid circles. The distance between this point and the end of the transposon is marked by the arrows terminating in diamonds. The length of the entire PCR product is marked by the two-headed arrows. The bp 1 and integrase termini are indicated in the top diagram.

Extraction of DNA for circularization assay.

Harvest of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen) containing the two plasmid vectors with different inserts occurred as follows. Cells were inoculated into LB broth containing selective antibiotics overnight with shaking at 37°C. Aliquots from the overnight cultures were inoculated at a ratio of 1:100 into fresh LB media containing antibiotics. After 2 h of growth, a zero time point 1-ml aliquot was removed, followed by the addition of IPTG to achieve a 1 mM concentration. Aliquots were removed at other time points as the culture continued to shake at 37°C. Total genomic DNA was extracted from cells in the removed aliquots as previously described (2). For one plasmid construct (pCWR1110 with the integrase and excisase from Tn5386), extraction of DNA after induction resulted in a large number of different PCR products. The zero time point extractions yielded a single PCR product for this combination, so for this combination, the zero time point (no induction) sample was used to extract PCR amplification products. Zero time point samples were also used when we repeated experiments designed to generate joints formed by the combination of pCWR1327 (Tn916 excisase and integrase) with the Tn916 termini (see below). In this second instance, the zero time point was used because the PCR product generated was the expected size and restriction digestion pattern.

DNA circularization assay.

Genomic DNA from the 1-ml cell aliquots at 1 h postinduction was extracted as described above, diluted 1:20 in sterile water, and then used as a template in PCR using a LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche) with PCR primers designed to detect the circularization of the two ends of the transposons (Table 2). The conditions varied for all of the primer sets.

PCR product resulting from circularization of construct was ligated to pCR-XL-TOPO and electroporated into E. coli CJ236, and sequencing of the putative joint regions was performed by Cleveland Genomics. Total DNA preparations of BL21(DE3) with plasmids at 1 h after IPTG induction were diluted and used as a template in a Roche FastStart PCR to determine quantities of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene in pACYC184 as a control for plasmid DNA quantity. Variation in DNA quantities was within a 10-fold range across circularization reactions (data not shown).

RESULTS

Circularization of Tn916 and Tn5386 constructs.

In control reactions, no PCR product was demonstrable when the ends of the transposons were tested in the presence of pCDF-1b lacking the integrase or excisase genes from either Tn916 or Tn5386 (data not shown), confirming that PCR products generated in the test reactions resulted from the action of the integrase constructs rather than an unknown mechanism present in the E. coli host. PCR products were generated from all cultures in which transposon ends and integrase genes were present in the same host. The nature of the PCR products varied with some of the combinations, as detailed below and in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4.

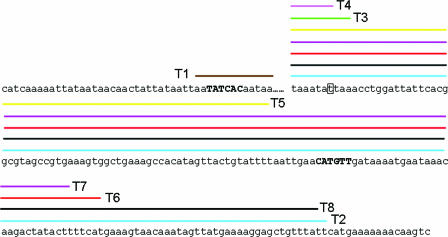

FIG. 3.

Tn5386 termini observed in these experiments. Sequence in boldface represents Tn5386. The boxed “t” represents the truncated end observed in experiments looking at excisants from the genome of E. faecium D344R (9). The uppercase and boldface 6-bp sequences represent the junction sequences identified in previous experiments of Tn5386 excision from the E. faecium D344R genome. The colored lines above the sequence represent the termini observed in joint sequences when the bp 1 and/or integrase termini of Tn5386 were include in the excision complex. The colors correspond to the colors used to depict the termini in Fig. 4.

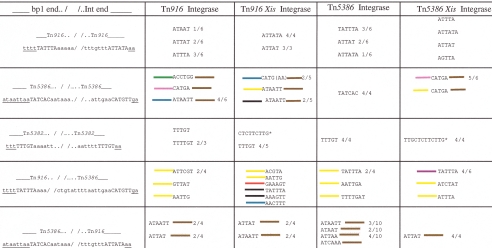

FIG. 4.

Sequences of joint sequences of PCR products resulting from circularization of transposon constructs. The colored lines correspond to the termini designated by the colored lines in Fig. 3.

Overall, most of the notable variations occurred when the termini of Tn5386 were involved in the excision. In all cases when the termini of Tn916 or Tn5382 were used, previously identified termini were observed adjacent to the joint sequences. The joint sequences themselves were also more consistent with expectations when the termini of Tn916 or Tn5382 were exclusively involved in the excision.

Tn916 integrase and excisase. (i) Tn916 integrase with Tn916 termini.

All PCR products analyzed from this combination contained the expected Tn916 termini (those identified in numerous previous studies and shown in the first column of Fig. 4). Five of six PCR joint regions consisted of the junction sequence present at the integrase end of the transposon (ATTAT; two of six products) or at the bp 1 end (ATTTA; three of six products). The final amplification product yielded a joint (ATAAT) that differed from the left end junction by one base. It is not clear whether this change is a mutation introduced by the integrase or by the amplification process. Seven products were originally analyzed that resulted from Tn916 termini excision associated with the Tn916 excisase and integrase. All seven joints analyzed were derived from the bp 1 junction, although some contained six nucleotides (ATTATA).

Because it was striking that all seven of the PCR products contained joints derived from the same junction sequence (at the integrase end of the integrated transposon), we repeated these experiments with newly transformed E. coli cells. Appropriate PCR products were generated only at zero time point in these experiments, and so zero time points samples were used. Of the additional four PCR products analyzed, all contained the ATTAT joint, indicating what appears to be a preference for this junction to be used when the Tn916 integrase and excisase forms a joint with its own termini.

(ii) Tn916 integrase and Tn5386 termini.

In six of six PCR products, the Tn916 integrase selected the 6-bp junction sequence, plus two additional adenines at the bp 1 end as the terminus (T1 in Fig. 3 and the brown line in Fig. 3 and 4). We had observed this terminus previously in analysis of the excision of the 170-kb region from the chromosome of E. faecium D344R (9). The distance of this terminus from the DR2 integrase-binding site corresponds almost exactly with the DR2 to terminus distance in Tn916, a correspondence that suggested that excision events in which this terminus was used were the result of Tn916 integrase (9).

The integrase terminus used by the Tn916 Integrase in four of six cases extended outside the normal terminus by 76 bp (T2, the blue line in Fig. 3) (9). In the remaining two PCR products, the integrase terminus at occurred 68 and 71 bp inside of the expected terminus (T3 and T4, pink and green lines in Fig. 3). T3 and T4 closely approximate the termini observed in the joints found in excision of large genomic sections from D344R in previous work (marked as a boxed “t” in Fig. 3). In four of six cases the joint sequence consisted of the 6 bp adjacent to the T1 (brown) terminus (ATAATT). In one other product, the joint used reflected the continued sequence beyond the T3 (green) terminus (ACCTGG; see Fig. 3). In the other product, the T4 terminus is found adjacent to the junction sequence of the T2 terminus (CATGA). When the Tn916 excisase was added to the experiment, all products used the T1 (brown) bp 1 terminus. Several different integrase termini and joints were identified (Fig. 4). In two instances, the T2 (blue) terminus was used, and the joint reflected two variants of the T2 junction sequence (CATG and CATGAA). In two other instances, a terminus 1 bp 5′ to the T2 terminus was used (T8, black line in Fig. 3). In both of these instances, the joint was derived from the junction at the bp 1 end (ATAATT). In the final instance, the T5 (yellow) terminus was used, with the joint also reflecting the sequence at the bp 1 junction.

(iii) Tn916 integrase with Tn5382 termini.

All PCR products sequenced from this combination contained the previously identified Tn5382 (2) termini and a 5-bp (TTTGT) or 6-bp (TTTTGT) joint consisting of the junction sequence [(T)TTTGT] present at both ends of the integrated transposon (Fig. 4). Interestingly, when the Tn916 integrase was present with its excisase, four of five products were consistent with those observed with integrase alone, but the fifth product was dramatically different. The bp 1 end was truncated by 43 bp compared to the typical end, whereas the integrase end was truncated by 19 bp. The sequence present between the two novel ends (CTCTTCTTG) was not present in the flanking sequences of the transposon. However, BLAST search revealed this sequence to be present in a putative prophage within a cryptic plasmid in E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (GenBank accession no. AE005174) located 43 bp downstream of a sequence (5′-ACATGAGGAAATAT-3′) that perfectly matched the excisase binding site previously identified by the Tn916 excisase protection assay (12).

(iv) Tn916 integrase with the bp 1 end of Tn916 and the integrase end of Tn5386.

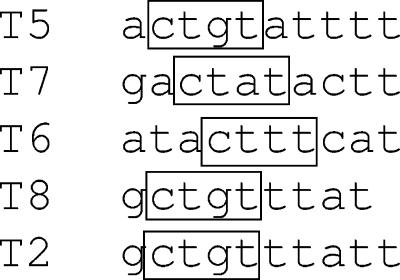

When the Tn916 integrase was present without excisase, four of four PCR products contained sequences with the expected bp 1 terminus of Tn916. The integrase terminus of Tn5386, however, was 6 bp internal to the transposon compared to the expected terminus (T5, yellow line in Fig. 3). Three different joint sequences (ATTCGT, GTTAT, and AATTG) were identified in the four PCR products. None of these joint sequences bore any relation to the junction sequences of the integrated ends. When the excisase was included with the integrase, the same end (T5, yellow) was found in two of six PCR products. One of these products had a joint that was found in the integrase-only products (AATTG); the other joint (ACGTA) was unrelated to any others. One of six PCR products contained the T2 (blue) integrase end. The joint sequence attached to this end (AACTTT) did not reflect either of the junctions. Two PCR products contained the T8 (black) terminus. One of these products contained a joint reflecting the junction sequence of the bp1 end (TATTTA). The other joint sequence (AAAGTT) was of unclear derivation. The final PCR product used a novel end present 39 bp downstream of the expected terminus (T6, red in Fig. 3). The joint used in this PCR product (GAAAGT) represented the junction at this new end. It is interesting that in each of these novel termini, the final base is located 4 or 5 bp downstream of a consensus CTXT sequence. For the T2, T5, and T8 termini, they are located 5 bp downstream of a CTGT. For the T6 terminus, it is located 4 bp downstream of a CTTT sequence (Fig. 3).

(v) Tn916 integrase with bp 1 end of Tn5386 and integrase end of Tn916.

In all four PCR products, the expected integrase end of Tn916 and the T1 (brown) end of Tn5386 were used. The joints of two of the products reflect the bp1 end junction sequence (ATAATT), whereas the other two reflected the integrase end junction sequence (ATTAT). The results were identical when the Tn916 excisase was present.

Tn5386 integrase and excisase. (i) Tn5386 integrase with Tn5386 termini.

PCR products analyzed from this combination contained the expected Tn5386 termini and a 6-bp joint consisting of the junction sequence present at the bp 1 end of the integrated transposon (TATCAC) in four of four cases (Fig. 3). These were the termini identified in previous work (9), where the same junction sequence was observed in all joint regions derived from in vivo excisants of Tn5386 itself from the genome of E. faecium D344R. When the Tn5386 excisase was present, five of six PCR products showed the T4 (pink) integrase end. The joint region of these products (CATGA) reflects the sequence adjacent to the T2 (blue) terminus. It should be noted that the sequence CATGA is also present within the T6 (red) terminus. Moreover, the sequence preceding the CATGA T2 junction sequence (TATT) is also present at the T4 (pink) terminus. In the sixth PCR product, the T5 (yellow) integrase terminus was used (GTATTTT). The joint region was also CATGA, reflecting a sequence 83 bp downstream.

(ii) Tn5386 integrase with Tn916 termini.

Six of six PCR products analyzed from this combination contained the expected Tn916 termini and 5- or 6-bp joints consisting of the junction sequence present at the right end of the integrated transposon (TATTTA; three of six products) or at the left end (ATTAT; two of six products; ATTATA; one of six products). When the excisase was present, the expected Tn916 termini were used in four of four cases. In three of four instances, the joint region reflected 5- or 6-bp junction sequences at either end (ATTTA, ATTATA, and ATTAT). In the remaining instance, the joint sequence varied from one of the junctions by a single base pair (ACTTA), which could reflect an amplification error.

(iii) Tn5386 integrase with Tn5382 termini.

Four of four PCR products identified from this combination contained the previously identified Tn5382 termini and a 5-bp joint consisting of the junction sequence (TTTGT) present at both ends of the integrated transposon. When the Tn5386 excisase was present, we again observed what appeared to be an integration into the E. coli genome downstream of the putative excisase binding site (see above). However, in all four PCR products, the apparent bp 1 terminus was 4 bp further downstream than observed with the Tn916 integrase and excisase, and the joint sequence contained an additional 3 bp.

(iv) Tn5386 integrase with bp 1 end of Tn916 and integrase end of Tn5386.

In four of four cases, the expected Tn916 bp 1 end was used. However, in all cases the T5 (yellow) integrase end of Tn5386 was used. Joints reflected the Tn916 bp 1 junction in two cases, the T5 Tn5386 integrase end junction in one case, and a sequence of unknown origin (TTTTGAT) in one case. When the excisase was present, the expected bp 1 end of Tn916 was used. A novel integrase terminus (T7, purple in Fig. 3) close to the T6 terminus was used in four of six products. The joint in each of these four cases reflected the 6-bp junction at the bp 1 end (TATTTA). In the remaining two products, the T5 (yellow) end was used. In one instance a 5-bp version of the bp 1 junction (ATTTA) was used in the joint. In the other, the joint (ATCTAT) was of unclear derivation.

(v) Tn5386 integrase with bp 1 end of Tn5386 and integrase end of Tn916.

In 10 of 10 products the bp 1 end of Tn5386 was the T1 (brown) terminus. The expected Tn916 integrase end was used in all cases. In 3 of 10 instances, the joint reflected the 6-bp junction at the bp 1 end of Tn5386 (ATAATT). In two cases the joint was a 5-bp variant of this junction (ATAAT). In 4 of 10 cases, the joint reflected the junction at the integrase end of Tn916 but was different by 1 bp (ATTAA instead of ATTAT). In the final case, the joint sequence (ATCAAA) was not consistent with either junction sequence. When the excisase was present, the same termini were used in four of four cases, with all joints reflecting 5 bp of the junction sequence at the integrase end of Tn916 (ATTAT).

DISCUSSION

Our data confirm that the integrases from both Tn916 and Tn5386 can promote excision of heterologous transposon constructs. They support our hypothesis that the large genomic excision observed in D344R was in fact the result of the action of either the Tn916 or the Tn5386 integrase (9). These data also provide a potential explanation for the mobility of elements such as Tn5398 (3), an ermB mobile element found in Clostridium difficile 630 that contains DR2 integrase-binding sites but does not contain ORFs that appear to encode an integrase or excisase. A Washington University 2.0 search using Tn5386 as the reference sequence reveals a C. difficile genome segment that, when excluding an intron and a putative bacitracin immunity region, has an 86% nucleic acid match to Tn5386 (C. difficile 630 chromosome complement 428617 … 456888 [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/BLAST/submitblast/c_difficile]) including ORFs with significant amino acid identities to the Tn5386 integrase (65% identical) and excisase (88% identical). Given our results, it is reasonable to suggest (as other authors had hypothesized more generally [3]) that the integrase encoded by this as-yet-unnamed element promotes excision of Tn5398 in trans.

The cloned integrases from Tn916 and Tn5386 were faithful to their in vivo counterparts when promoting excision of their own ends, adhering precisely to termini that have been determined by examining excisants from intact transposons in their native hosts. Both integrases, when working without their associated excisases, also recognize the Tn916 and Tn5382 termini.

The greatest degree of variability we observed in the termini present in joints was when the termini of Tn5386 were included in the excision constructs. The bp 1 end of Tn5386 marked T1 (brown) in Fig. 3 was used by both Tn916 and Tn5386 integrases in all circumstances except when the Tn5386 integrase alone was used with Tn5386 ends. We observed the T1 terminus to be used in prior experiments in E. faecium D344R (9), and because it better approximated the distance between the DR2 integrase-binding site and the transposon terminus of Tn916, we hypothesized that, in E. faecium, it represented the activity of the Tn916 integrase on the heterologous ends of Tn916 and Tn5386. Our results in this work do not support that hypothesis, since the Tn5386 integrase, when promoting excision of heterologous transposon termini, uses this terminus as well. It would appear from these results that the sequence of the integrase end exerts an influence on the bp 1 terminus chosen by the Tn5386 integrase. Moreover, it appears that the presence of the Tn5386 excisase favors the choice of the T1 terminus by Tn5386 integrase as well, even when both Tn5386 termini are present in the constructs.

Jia and Churchward (5) previously proposed a model of Tn916 integrase action in which the N-terminal portions of two integrase molecules bind cooperatively to the DR2 binding site of one end of Tn916, and their C-terminal ends bind to the contiguous and contralateral termini, thereby bringing the transposon ends closer together to facilitate strand breakage and exchange. These results are consistent with this model, in that the model would provide a plausible mechanism for the sequence of the contralateral terminus exerting an impact on the choice of contiguous ends.

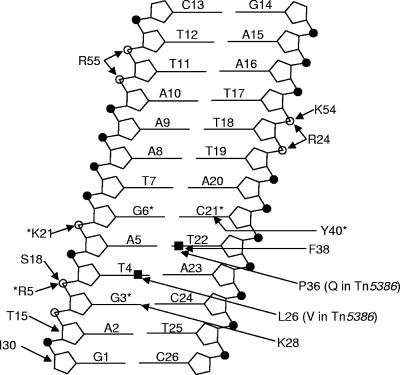

It is perhaps not surprising that the Tn916 and Tn5386 integrases can work interchangeably in promoting excision. Using NMR spectroscopy, Wojciak et al. (14) determined the solution structure of the DNA-binding domain of the Tn916 integrase bound to its target DNA. These authors defined several amino acids and nucleotides that appear to be involved in the binding of the protein to DNA. The amino acids identified and the nucleotides they are proposed to interact with are shown in Fig. 5. A comparison of the Tn916 and Tn5386 integrase sequences indicates that only 2 of the 14 amino acids identified as involved in binding by Wojciak et al. differ between the Tn916 and Tn5386 integrases. These two amino acids, proline 36 and leucine 26, are proposed to interact with the methyl groups of thymine 4 and thymine 22 (Wojciak numbering) by van der Waals forces. In the Tn5386 integrase, leucine 26 has been replaced by valine, and proline 36 has been replaced by glutamine. Importantly, neither the amino acids nor the nucleotides involved in these proposed interactions involve hydrogen bonds. Wojciak et al. tested the impact of hydrogen bonding by changing the guanine at position 3 to an adenine, which resulted in a 90% decrease in affinity (14). Based on the analysis of Tn916 integrase interaction with DNA reported by Wojciak et al., one could predict strong binding of the Tn5386 integrase to the Tn916 direct repeat binding site and vice versa.

FIG. 5.

Interactions between the Tn916 Int protein and the Tn916 direct repeat as discerned from NMR studies of the structure of the INT-DNA-binding domain-DNA complex by Wojciak et al. (14) (our figure is based on a similar figure from their publication). Arrows connect the INT-DBD residues to their DNA interaction sites. Open and closed circles represent phosphate and methyl groups that interact with INT-DBD, respectively. Residues and bases involved in hydrogen bonding are indicated by asterisks. The two residues that differ between the Int of Tn916 and Tn5386 in this region are indicated in parentheses, neither of which is involved in significant hydrogen bonding.

The observed wide variety of Tn5386 integrase ends used by both integrases was unexpected. In previous work analyzing excisions of large genomic fragments in E. faecium D344R, we observed either the expected Tn5386 integrase terminus or one that was truncated by more than 70 bp. Since this truncated terminus corresponded almost perfectly with the distance from the DR2 integrase binding site in Tn916 and its terminus, we hypothesized that it was the Tn916 integrase that was promoting those excisions that used this end. The data presented here do not confirm this interpretation, since ends truncated by that much were observed only when the Tn916 integrase was acting on both Tn5386 ends, rather than on mismatched ends as would have occurred to create the large genomic deletions seen in D344R. When the Tn5386 integrase end was combined with the Tn916 bp 1 end, a variety of Tn5386 integrase ends were used (T2, T5, T6, T7, and T8), but none of these were similar to the truncations seen in previous E. faecium experiments or in these experiments when Tn916 integrase acted on both Tn5386 ends. The variations in distance from the expected end were surprising and suggest that distance is not the controlling factor for integrases choosing the location that they will use as termini.

It seems likely that sequence exerts an effect, since some similarities exist between the sequences near the different termini. A comparison of the novel Tn5386 integrase termini is shown in Fig. 6. Although the sequences are quite diverse, they are all relatively A-T rich, a finding consistent with Tn916 termini. In addition, a consensus c-t-x-t sequence (boxed in Fig. 6) is present in each terminus. The exceptions to this rule are the T3 and T4 termini (not shown in Fig. 6). These termini, however, closely approximate termini we observed in earlier experiments in E. faecium D344R, in which the distance between the DR2 repeats and their termini closely approximates the distance seen in Tn916.

FIG. 6.

Sequences of five of the aberrant Tn5386 integrase termini observed in this work. The consensus c-t-x-t sequence in each terminus is boxed.

In an effort to determine whether there were minimal sequence requirements for excision, we created a construct in which the DR2 sites (separated by ca. 500 bp of enterococcal genomic DNA) were flanked by pACYC184 DNA (in other words, there was no enterococcal DNA outside of the DR2 direct repeats). Under these circumstances we did not observe any PCR products (data not shown) suggesting that sequence requirements do exist for integrase-mediated excision of these elements.

Previous work has indicated that excisase binding to the ends of Tn916 can either promote or inhibit excision, depending on which excisase binding site is occupied (4). It has been postulated that excisase binding to the left (integrase) end of Tn916 promotes excision by bending the DNA in a manner that facilitates integrase activity (4). The variety of influences attributed to the presence of excisase in our experiments was unexpected. None of these effects were more dramatic than observed when either the Tn916 or the Tn5386 excisases were combined with their corresponding integrases to promote excision of the Tn5382 construct. In contrast to experiments in which the integrase was present alone, the Tn5382 ends chosen were both truncated. The 9- or 12-bp sequences that appeared to be the joint region of these products were not related to either of these ends but were found within the genome of E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 [we do not know whether this specific sequence is also present in BL21(DE3)]. At 42 bp upstream of this sequence within the E. coli genome lies a 15-bp sequence (ACATGAGGAAATATG) that matches precisely a sequence within the binding region for the Tn916 excisase (12). Tn5386 has sequence similar to the Tn916 excisase binding site. In contrast, there is no good consensus sequence for Tn916 excisase binding in Tn5382 (2). It is thus tempting to suggest that excisase binding to the E. coli genome promoted a transposon construct excision that utilized the observed downstream sequence as a joint. The mechanism by which this could happen is not immediately obvious, using known mechanisms of Tn916 integration and excision.

Another major change attributable to the presence of excisase were the termini and joint regions found when the Tn5386 integrase and excisase promoted excision of the Tn5386 construct. The use of the T1 terminus at the bp 1 end and the T2 and T4 integrase termini were reminiscent of results seen with the Tn916 integrase-excisase combination, suggesting that an interaction between the Tn5386 integrase terminus and excisase may result in changes in the Tn5386 integrase that would make it behave more like the Tn916 integrase.

The presence of the Xis protein may also exert an influence over the junction sequence observed the joint region amplification products. When Tn916 Int and Xis were both present, the integrase end junction sequence of Tn916 was present in the joint in 11 of 11 joints examined. In comparison, the joints from excisants with the Tn916 Int alone demonstrated a relatively equal balance between the two junction sequences. This result could be observed if the presence of excise has an inhibitory effect on one of the strand exchanges that occurs during excision. In that circumstance, excision might not proceed to completion. The Holiday junction that is thus formed could be resolved by replication, but the PCR would only amplify one of the strands, containing only one of the coupling sequences.

Among our more interesting observations was that some joints contained sequences that reflected junctions of other alternative transposon ends (such as the T4 end [AAATATT] with a joint reflecting the T2 junction sequence [CATGA]). The most likely explanation for this observation is a second insertion event at the T2 site preceding the excision that was amplified and sequenced. The second insertion would result in at least one junction sequence of CATGA, which could then be incorporated into a subsequent excision. The observation of this type of joint over several reactions suggests that the T2 site may be a “hotspot” for insertion. Since binding of the target site is a function carried out by the C-terminal end of the integrase molecule, the use of this sequence as a target site and as a terminus for excision would be reasonable. The joint regions we observed that bore no resemblance to either junction in other reactions may also reflect second insertion events prior to PCR amplification.

It is tempting to speculate that the presence of the excisase promoted excision to a greater degree than integrase alone and that this increased frequency of excision causes the appearance of different joint sequences (due to secondary insertion sites). Overall, the numbers do not bear this out, since the aberrant joint sequences observed for Tn916 integrase alone (6 of 24), Tn916 integrase and excisase (5 of 28), and Tn5386 integrase alone (6 of 28) are quite similar. The rates for the Tn5386 integrase and excisase combination are somewhat higher (12 of 24). The presence of discordant ends could also exert an influence on the joint sequences, since aberrant joints were found in 15 of 45 instances where the ends were discordant compared to 14 of 62 instances when the ends were matched regarding origin.

A limitation of the present study is the fact that the excision experiments were performed in E. coli, which is not the native host for Tn916-like elements. It is possible that host factors present in Enterococcus, for example, work with transposon-encoded integrases and excisases to ensure that excision is precise and specific. The behavior of Tn916-like elements does vary with the species. For example, transposition sites in enterococci tend to be nonselective if not completely random. In contrast, insertion of Tn916-like elements into the C. difficile genome occurs into a single site (13). We are in the process of developing the constructs that will allow us to replicate these experiments in an enterococcal background.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated broader substrate specificity than previously suspected for at least two Tn916-like integrases. Under the conditions of our experiments, excision of integrated transposon constructs was readily demonstrable when transposon ends were acted on by heterologous integrases, and even when the transposon ends that were acted on were from different transposons. The widespread presence of Tn916-like elements in many gram-positive genomes suggests that these elements have a broad capacity to influence genome evolution in the species they inhabit.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by a Merit Review from the Department of Veterans Affairs (L.B.R.) and by grant number AI 045626-05 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (L.B.R.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caparon, M. G., and J. R. Scott. 1989. Excision and insertion of the conjugative transposon Tn916 involves a novel recombination mechanism. Cell 59:1027-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carias, L. L., S. D. Rudin, C. J. Donskey, and L. B. Rice. 1998. Genetic linkage and cotransfer of a novel, vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) and a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 gene in a clinical vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate. J. Bacteriol. 180:4426-4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrow, K. A., D. Lyras, and J. I. Rood. 2001. Genomic analysis of the erythromycin resistance element Tn5398 from Clostridium difficile. Microbiology 147:2717-2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinerfeld, D., and G. Churchward. 2001. Xis protein of the conjugative transposon Tn916 plays dual opposing roles in transposon excision. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1459-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia, Y., and G. Churchward. 1999. Interactions of the integrase protein of the conjugative transposon Tn916 with its specific DNA binding sites. J. Bacteriol. 181:6114-6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu, F., and G. Churchward. 1994. Conjugative transposition: Tn916 integrase contains two independent DNA binding domains that recognize different DNA sequences. Eur. Mol. Biol. Org. J. 13:1541-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manganelli, R., S. Ricci, and G. Pozzi. 1997. The joint of Tn916 circular intermediates is a homoduplex in Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 38:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poyart-Salmeron, C., P. Trieu-Cuot, C. Carlier, and P. Courvalin. 1989. Molecular characterization of the two proteins involved in the excision of the conjugative transposon Tn1545: homologies with other site specific recombinases. Eur. Mol. Biol. Org. J. 8:2425-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice, L. B., L. L. Carias, S. Marshall, S. D. Rudin, and R. Hutton-Thomas. 2005. Tn5386, a novel Tn916-like mobile element in Enterococcus faecium D344R that interacts with Tn916 to yield a large genomic deletion. J. Bacteriol. 187:6668-6677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose, R. E. 1988. The nucleotide sequence of pACYC184. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudy, C. K., and J. R. Scott. 1994. Length of coupling sequence of Tn916. J. Bacteriol. 176:3386-3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudy, C. K., J. R. Scott, and G. Churchward. 1997. DNA binding by the Xis protein of the conjugative transposon Tn916. J. Bacteriol. 179:2567-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, H., A. P. Roberts, and P. Mullany. 2000. DNA sequence of the insertional hot spot of Tn916 in the Clostridium difficile genome and discovery of a Tn916-like element in an environmental isolate integrated in the same hot spot. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 192:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojciak, J. M., K. M. Connolly, and R. T. Clubb. 1999. NMR structure of the Tn916 integrase-DNA complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:366-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]