Abstract

The synthesis of citrate from acetyl-coenzyme A and oxaloacetate is catalyzed in most organisms by a Si-citrate synthase, which is Si-face stereospecific with respect to C-2 of oxaloacetate. However, in Clostridium kluyveri and some other strictly anaerobic bacteria, the reaction is catalyzed by a Re-citrate synthase, whose primary structure has remained elusive. We report here that Re-citrate synthase from C. kluyveri is the product of a gene predicted to encode isopropylmalate synthase. C. kluyveri is also shown to contain a gene for Si-citrate synthase, which explains why cell extracts of the organism always exhibit some Si-citrate synthase activity.

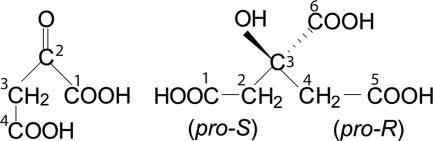

In 1937, Hans Krebs summarized the evidence for a cyclic sequence of reactions in pigeon breast muscle, which he dubbed the citric acid cycle and which could explain the complete oxidation of pyruvate to 3 CO2 (30, 47). However, 4 years later, the involvement of citric acid in this cycle was seriously questioned. It was shown by Harland Wood and by Earl Evans that 2-oxoglutarate synthesized from pyruvate and 14CO2 in pigeon liver was almost exclusively labeled in the carboxyl group adjacent to the carbonyl group (9, 53). This result appeared to exclude a symmetric intermediate, such as citric acid. At that time, it was generally assumed that enzymes handled compounds like citric acid as a symmetric molecule. Then, in 1948, Alexander Ogston revealed a fallacy in this assumption and proposed that both citrate synthase and aconitase could interact with citric acid so that the two -CH2-COOH groups of citric acid do not react identically (37). Indeed, it was later shown that the citrate synthase involved in the citric acid cycle incorporates acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) only into the (pro-S) carboxymethyl group and that the aconitase abstracts a hydrogen only from the (pro-R) carboxymethyl group of citrate (20, 38) (Fig. 1). The citrate synthase with this stereospecificity has, since 1971, been referred to as Si-citrate synthase (34). The work of Ogston was the start of a large branch of stereochemistry of compounds that behave like citrate (3, 29).

FIG. 1.

Structures of oxaloacetate and of citrate. Oxaloacetate is viewed from its Re-face.

In 1954, Tomlinson demonstrated that the origin of the carbon atoms in glutamate synthesized in Clostridium kluyveri growing on 14C-labeled ethanol, acetate, and CO2 is unusual (49), and this was later confirmed (25). Twelve years later, Gottschalk and Barker (15) showed that this anaerobic bacterium contains a Re-citrate synthase, which explained the unusual labeling pattern observed in glutamate. The citrate synthesized from [14C]acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate was 88% (3R)-citrate and 12% (3S)-citrate (14). A Re-citrate synthase was also found to be present in other anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium acidi-urici, Clostridium cylindosporum, Desulfovibrio vulgaris, and Desulfovibrio desulfuricans, but not in Clostridium pasteurianum or Clostridium thermoaceticum (Morella thermoacetica) (13, 14). The >99% stereospecific Re-citrate synthase from C. acidi-urici was partially purified and characterized (12, 17, 54). Re-citrate synthase was found to require Mn2+ or Co2+ for activity, to be O2 sensitive, and to be inactivated by p-chloromercuribenzoate (pCMB), properties unusual for most Si-citrate synthases (12, 16). Information on the subunit composition, molecular mass, and primary structure of the Re-citrate synthase was not published.

In 1969, O'Brien and Stern reported that the Re-citrate synthase activity in cell extracts of C. kluyveri could be reversibly changed to the Si-type by incubating the cell extract with pCMB (36). This effect was later explained by assuming that the cell extracts contained both Si-citrate synthase and Re-citrate synthase activities, whereby only the Re-citrate synthase activity was affected by pCMB (8). However, neither the Si- nor the Re-citrate synthase from C. kluyveri had been purified and characterized. Their phylogenetic relationship thus remained unknown.

In this communication, we describe the identification of the genes for Si- and Re-citrate synthases in the genome of C. kluyveri, whose draft sequence has recently been determined (unpublished results). The respective genes were heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli, and the substrate specificities and stereospecificities of the overproduced and purified enzymes were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and chemicals.

Citrate lyase from Aerobacter aerogenes (Si-face specific), malate dehydrogenase, acetyl-CoA synthetase, and acetyl-CoA were purchased from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). [2-14C]acetic acid, sodium salt (1 mCi/5 ml; 57 mCi/mmol), was obtained from GE Healthcare (Freiburg, Germany). C. kluyveri (DSM555) was from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). The anaerobic bacterium was grown on ethanol and acetate.

Heterologous expression of the genes predicted to encode Si-citrate synthase and IPMS1 and -2.

DNA was isolated from C. kluyveri by employing conventional procedures. The putative genes for Si-citrate synthase and for isopropylmalate synthases 1 and 2 (IPMS1 and -2) (Fig. 2) were amplified by PCR using Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The following primers were used: 5′-CACCATGGATAATATGGATTTAG-3′ and 5′-CATTCTATTTTCTAAAG-3′ for Si-citrate synthase; 5′-CACATGCACAATTATAAAAAAT-3′ and 5′-TTATTATATTTGTCCCG-3′ for IPMS1; and 5′-CACCATGAAAAAATGTCCC-3′ and 5′-TTAGCTAGCTCTTTCTTCTG-3′ for IPMS2 (CACC was added for directional cloning). The PCR product was separated by gel electrophoresis on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel, and the appropriate band was excised and extracted using a gel extraction kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The gene was cloned into pET200 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), a Champion pET directional TOPO expression plasmid with a 5′ His6 cassette, and transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells. The authenticity of the amplified gene was subsequently verified by DNA sequencing. For overexpression, the plasmid was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The cells were grown aerobically in 2 liters of tryptone-phosphate medium at 37°C to an absorbance difference at 600 nm of 0.6 to 0.8. Expression of the cloned gene was then induced by adding 1 mM isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside. After 3.5 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min.

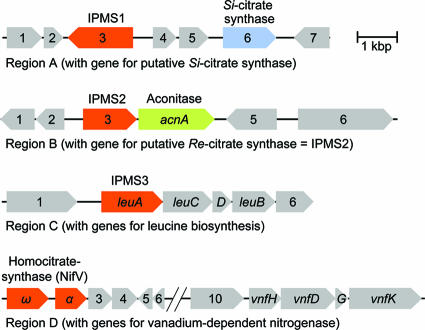

FIG. 2.

Regions in the genome of C. kluyveri harboring putative genes for Si-citrate synthase, IPMS, and homocitrate synthase. The homocitrate synthase is composed of the two subunits ω and α, each of which has sequence identity to different portions of IPMS. (Region A) CDS 1, predicted phosphatidylserine decarboxylase; CDS 2, predicted acetyltransferase; CDS 4 and 5, both conserved hypothetical proteins; CDS 7, transcriptional regulator. (Region B) CDS 1, predicted hydrolase; CDS 2, predicted acyltransferase; CDS 5, O-acetyl-l-homoserine sulfhydrylase-related protein; CDS 6, predicted methionine synthase. (Region C) CDS1, predicted methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein; CDS 6, transcriptional regulator. (Region D) CDS 3, FeMo-cofactor biosynthesis-related protein; CDS 4, conserved hypothetical proteins; CDS 5 and 6, nitrogen regulatory protein P-II and P-I; CDS 7, 8, and 9, hypothetical proteins; CDS 10, FeMo-cofactor biosynthesis-related protein.

Purification of the N-terminal His6-tagged proteins.

Purification was performed under strictly anoxic conditions in an anaerobic chamber (Coy, Ann Arbor, MI) filled with 95% N2-5%H2 and containing a palladium catalyst for O2 reduction with H2. E. coli cells were suspended in buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and disrupted by sonication. The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 120,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded on an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) column (1.6 cm by 15 cm), which was washed with buffer A to remove proteins that were nonspecifically attached to the resin. The His-tagged protein was eluted using buffer A with increasing concentrations of imidazole (a linear gradient from 10 mM to 250 mM; 180 ml). Purification was followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (32). The purified protein was concentrated by ultrafiltration; washed with 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; and then stored under anoxic conditions at 4°C until it was used.

Determination of citrate synthase, IPMS, and citramalate synthase activities.

The assays were performed at 25°C under anoxic conditions. The assay mixture contained, in a final volume of 1 ml, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 0.2 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid); 0.2 mM MnCl2 (only in the cases of Re-citrate synthase and IPMS); 0.2 mM oxaloacetate (potassium salt), 0.2 mM 2-oxo-3-methylbutanoate (potassium salt) or 0.2 mM pyruvate (sodium salt); and 0.1 mM acetyl-CoA. The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme and monitored by following the formation of the anion of thionitrobenzoate from 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (Ellmans reagent) and CoA at 412 nm spectrophotometrically (ɛ412 = 13,600 M−1 cm−1) (42).

Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard (1).

Determination of the stereospecificity of citrate synthase.

Citrate was synthesized from oxaloacetate and [2-14C]acetyl-CoA with citrate synthase, and the [14C]citrate thus generated was subsequently cleaved to oxaloacetate and acetate with Si-citrate lyase. In the case of Si-citrate synthase, the products formed were oxaloacetate plus [2-14C]acetate, and in the case of Re-citrate synthase, the products were [14C]oxaloacetate plus acetate.

(i) [14C]citrate synthesis.

The synthesis was performed under anoxic conditions. The 2-ml reaction mixture contained 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.2 mM MnCl2, 1 mM sodium citrate, 0.1 U purified Si- or Re-citrate synthase; 1 mM [2-14C]acetyl-CoA (generated in the assay from 1 mM [2-14C]acetate [11 × 106 dpm/μmol = 1.83 × 105 Bq/μmol], 0.5 mM CoA, and 1 U acetyl-CoA synthetase), 2.5 mM ATP, and 10 mM oxaloacetate (potassium salt) (4, 13). After incubation for 30 min at 25°C, the reaction was stopped by heating the mixture to 95°C for 10 min. Proteins were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was applied to a 0.8-cm by 4-cm column, AG 1-8× formate (200 to 400 mesh) (Bio-Rad, München, Germany), at room temperature. After the column was washed with 10 volumes of water followed by 10 volumes of 1 M formic acid, whereby unreacted [2-14C]acetic acid was eluted, the citric acid was eluted with 4 M formic acid in approximately 6 ml. The fractions obtained were combined and concentrated to dryness by flash evaporation, and the citric acid was then redissolved in 1 ml 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, containing 0.2 mM MgCl2. The solution had a radioactive content of approximately 2 × 106 dpm (18 × 103 Bq)/ml, which was determined by liquid scintillation counting in 2 ml Quicksave A scintillation fluid (Zinsser Analytic, Frankfurt am Main, Germany).

(ii) [14C]citrate cleavage.

The 1-ml reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, 0.2 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM NADH, 18 U malate dehydrogenase, 0.25 U citrate lyase (Si-face specific) (26), and an aliquot of the solution of [14C]citrate synthesized and purified as described above. After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, the sample was heated for 10 min at 95°C. Precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was applied to a 0.8-cm by 2-cm column, AG 1-8× formate (200 to 400 mesh) (Bio-Rad), at room temperature. Acetate was eluted with 0.2 M formic acid and malate with 1 M formic acid. Fractions of 1 ml were collected, 0.1 ml of each fraction was added to 2 ml Quicksave A scintillation fluid, and the 14C radioactivity (dpm) was determined by liquid scintillation counting (13).

RESULTS

To identify the gene encoding Re-citrate synthase, it was considered that the enzyme should not have amino acid sequence similarity to Si-citrate synthases but that it could show sequence similarity to homocitrate synthase and 2-IPMS. These two sequence-related enzymes are Re-face stereospecific with respect to C-2 of their substrates, 2-oxoglutarate and 2-oxo-3-methylbutyrate, respectively (2, 48). (There are other Re-face-stereospecific enzymes distantly related to IPMS, but homologues of their genes are not found in the genome of C. kluyveri [see Discussion]). In the genome of C. kluyveri, protein-coding sequences (CDS) were found that were predicted to encode a Si-citrate synthase, homocitrate synthases (two subunits), and three different IPMSs (IPMS1 to -3) (Fig. 2). The two CDS for homocitrate synthase (each showing sequence similarity to different portions of IPMS) (51) are located within a gene cluster encoding a vanadium-dependent nitrogenase and were therefore not further considered. (The genome of C. kluyveri also contains gene clusters encoding a molybdenum-dependent nitrogenase and a nitrogenase containing only iron; however, these clusters are devoid of CDS for homocitrate synthase). One of the CDS for IPMS (IPMS3) is located within a gene cluster predicted to encode enzymes required in leucine biosynthesis, in which IPMS (LeuA) has an essential function. This leaves two CDS for IPMS, one of which (IPMS2) is adjacent to a CDS predicted to encode aconitase (AcnA) while the other (IPMS1) is in the neighborhood of the CDS encoding a Si-citrate synthase (Fig. 2). Because of its location adjacent to the aconitase gene, the CDS for IPMS2 was predicted to encode Re-citrate synthase.

The putative genes for Si-citrate synthase, for IPMS1, and for IPMS2 were tagged at the 5′ end with a His6 cassette and individually expressed in E. coli, and the N-terminal His6-tagged proteins were purified and tested for activity. Only the putative Si-citrate synthase and IPMS2 showed citrate synthase activity. IPMS1 was completely inactive when tested for citrate synthase, IPMS, and citramalate synthase enzyme activities and was therefore not further investigated.

Si-citrate synthase from C. kluyveri.

The putative gene for Si-citrate synthase (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) is 1,347 bp long and is predicted to encode a 449-amino-acid polypeptide with a mass of 51.1 kDa. The polypeptide has the highest amino acid sequence identity of 66% to Si-citrate synthase from Clostridium thermocellum and of 34% to the well characterized Si-citrate synthase from Pyrococcus furiosus, for which a crystal structure has been determined (39). Heterologous expression yielded a protein with a molecular mass of 51 kDa, as revealed by SDS-PAGE (not shown).

The purified protein catalyzed the synthesis of citrate from oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA with a specific activity of 0.9 U/mg protein. The activity was not affected by O2, pCMB (50 μM), or EDTA (50 μM) and showed no Mn2+, Co2+, or Mg2+ dependency.

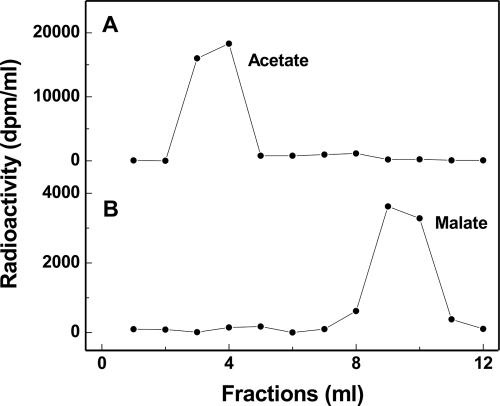

To determine the stereospecificity of the enzyme, [2-14C]acetyl-CoA was employed as a substrate. The radioactively labeled citrate was subsequently hydrolyzed to oxaloacetate and acetate by the catalytic action of Si-citrate lyase. After enzymatic conversion of oxaloacetate to malate and separation from acetate via anion-exchange chromatography, all the radioactivity was found in acetate and none was found in malate (Fig. 3A). This finding clearly indicates that the citrate synthase heterologously produced in E. coli is a Si-citrate synthase.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the [14C]citrate synthesized from [2-14C]acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate by Si-citrate synthase and the IPMS2 paralogue from C. kluyveri. After separation, the [14C]citrate was converted to acetate and malate in the presence of Si-citrate lyase, NADH, and malate dehydrogenase. Acetate and malate were subsequently separated via anion-exchange chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. The first six fractions were eluted with 0.2 M formic acid, and the following fractions with 1 M formic acid. (A) The separation of [14C]acetate formed from [14C]citrate synthesized from [2-14C]acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate in the presence of Si-citrate synthase. (B) The separation of [14C]malate formed from [14C]citrate synthesized from [2-14C]acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate in the presence of IPMS2.

Re-citrate synthase in C. kluyveri and other clostridia.

The putative gene for IPMS2 (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) is 1,359 bp long and is predicted to encode a 453-amino-acid polypeptide with a mass of 52.1 kDa. The polypeptide has a sequence identity of 25% to IPMS3 (LeuA) from C. kluyveri and of 18% to LeuA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, for which a crystal structure has been reported (28). In the active sites of IPMS2 and of LeuA from M. tuberculosis, most of the catalytic amino acid residues are conserved. Heterologous expression of the gene for IPMS2 yielded a protein with a molecular mass of 51 kDa, as revealed by SDS-PAGE (not shown).

The purified IMPS2 gene product catalyzed the synthesis of citrate from oxaloacetate (apparent Km = 40 μM) and acetyl-CoA (apparent Km = 50 μM), with a specific activity of 1.3 U/mg protein. In 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, the citrate synthase (9 μg/ml) was inactivated by 2 μM pCMB (50% in 10 min), by 50 μM EDTA (almost immediately), and slowly under aerobic conditions (50% in 24 h) (the inactivation rates were determined at room temperature). EDTA-inactivated enzyme regained activity upon addition of Mg2+, Mn2+, or Co2+ ions to a final concentration of 0.2 mM. Co2+ and Mn2+ were most effective in restoring activity. Zn2+ at 0.2 mM inhibited the enzyme. The catalytic properties were thus very similar to those reported for Re-citrate synthase purified from C. acidi-urici (16).

To determine the stereospecificity of the enzyme, [2-14C]acetyl-CoA was employed as a substrate. The radioactively labeled citrate was subsequently hydrolyzed to oxaloacetate and acetate by the catalytic action of Si-citrate lyase. After enzymatic conversion of oxaloacetate to malate and separation from acetate via ion-exchange chromatography, all the radioactivity was found in malate and none was found in acetate (Fig. 3B). This finding clearly indicates that the gene predicted to encode IPMS2 (Fig. 2) actually encodes a Re-citrate synthase. The fact that practically no labeled acetate was found indicates that the enzyme is highly Re-face stereospecific with respect to the C-2 of oxaloacetate.

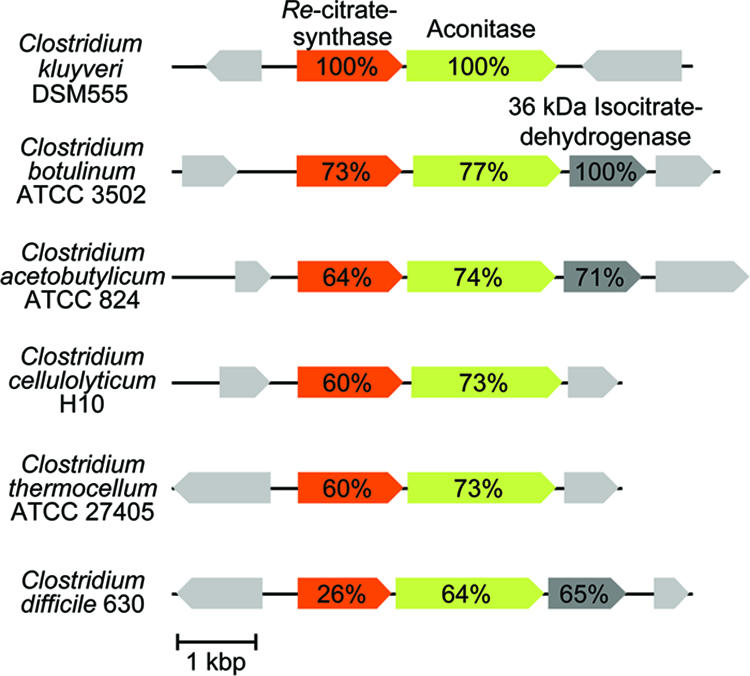

On the genome level, the function of IPMS2 as citrate synthase is substantiated by the observation that in three of the six clostridia listed in Fig. 4, the gene annotated as IPMS2 is not only located together with a gene for aconitase, but also with one for isocitrate dehydrogenase. The three other clostridia also harbor a gene for isocitrate dehydrogenase, but this gene is located elsewhere in the genome. In most clostridia, citrate synthase, aconitase, and isocitrate dehydrogenase are required for the synthesis of 2-oxoglutarate, and thus also of glutamate. Exceptions are, e.g., Clostridium tetani and Clostridium perfringens, which are dependent on glutamate for growth. Of the six clostridia listed in Fig. 4, only C. kluyveri, Clostridium cellulolyticum, and C. thermocellum harbor a gene for Si-citrate synthase.

FIG. 4.

Clostridia containing a Re-citrate synthase homologous gene adjacent to a gene coding for aconitase. In the genomes of three of the six clostridia shown, there is also a gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase (36-kDa type) that belongs to the cluster. In C. kluyveri, C. cellulolyticum, and C. thermocellum, a gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase (45-kDa type) is located elsewhere in the genome. C. kluyveri, C. cellulolyticum, and C. thermocellum all have a gene encoding a Si-citrate synthase, which is absent from the genomes of C. botulinum, C. acetobutylicum, and C. thermocellum. C. tetani and C. perfringens, which are not listed in this figure, do not have genes encoding Si- or Re-citrate synthase, aconitase, or isocitrate dehydrogenase.

There are two types of isocitrate dehydrogenases in clostridia, one with a molecular mass of ca. 45 kDa and the other with a molecular mass of ca. 36 kDa, which are phylogenetically only distantly related. Interestingly, the three clostridia with a Re-citrate synthase-aconitase-isocitrate dehydrogenase gene cluster (Fig. 4) all contain a 36-kDa isocitrate dehydrogenase, whereas the three clostridia in which the gene for isocitrate dehydrogenase is located separately have a 45-kDa isocitrate dehydrogenase.

The clostridia listed in Fig. 4 all have an IPMS homologue, which, based on its amino acid sequence similarity to LeuA and its location in the leucine biosynthesis gene cluster, is the actual IPMS.

Re-citrate synthase from C. kluyveri does not catalyze the synthesis of isopropylmalate from 2-oxo-3-methylbutyrate and acetyl-CoA. This is not too surprising, since the protein shares at most 25% sequence identity with IPMSs (LeuA). However, Re-citrate synthase from C. kluyveri shares with IPMSs a sensitivity to EDTA and mercuric salts (27) and the dependence of activity on the presence of either Mg2+, Mn2+, or Co2+ rather than of Zn2+ ions (6). Indeed, alignment of the primary structures of Re-citrate synthase from clostridia and of IPMS from M. tuberculosis, for which a crystal structure is available (28), revealed that the amino acids involved in metal binding and also one cysteine are conserved (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Why Re-citrate synthase is inactivated under oxic conditions and IPMSs are not is not presently understood.

Re-citrate synthase in deltaproteobacteria.

D. vulgaris and D. desulfuricans have been also reported to contain a Re-citrate synthase (13). The respective genomes of these bacteria have three genes annotated as IPMS but no gene for Si-citrate synthase (21; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi??db=nucleotide&val=CP000112). The IPMS genes DVU0398 in D. vulgaris and Dde_0520 in D. desulfuricans both encode products with 48% amino acid sequence identity to Re-citrate synthase from C. kluyveri. It is therefore most likely that the gene DVU0398 in D. vulgaris and the gene Dde_0520 in D. desulfuricans encode a Re-citrate synthase, despite the fact that these genes are not located near the genes for aconitase and isocitrate dehydrogenase.

The genome of Syntrophus aciditrophus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/viewer.fcgi?db=Nucleotide&dopt=GenBank&val=85720936), which, like D. vulgaris and D. desulfuricans, belongs to the deltaproteobacteria, has a gene for IPMS whose product has 49% amino acid sequence identity to Re-citrate synthase of C. kluyveri. Genes coding for aconitase and isocitrate dehydrogenase are not colocalized, and a gene encoding Si-citrate synthase is lacking.

Besides the gene for Re-citrate synthase, the three deltaproteobacteria also contain a gene coding for IPMS, which on the protein level shows high sequence similarity to LeuA and which is located in the leucine-biosynthetic gene cluster.

DISCUSSION

The results show that C. kluyveri contains both a Si- and a Re-citrate synthase and can explain why experiments with cell extracts of the organism previously have yielded different results with respect to the stereospecificity of the clostridial citrate synthase (8, 13, 14, 36, 43, 44). They also clearly show that Si-citrate synthase and Re-citrate synthase are phylogenetically unrelated, as there is no significant sequence similarity detectable. The finding that Re-citrate synthase is O2 sensitive whereas Si-citrate synthase is not also explains why Re-citrate synthase appears to be restricted to anaerobic microorganisms.

Si-citrate synthase shares sequence similarity with methylcitrate synthase, which is involved in propionate metabolism (11, 46). Consistent with this is the finding that methylcitrate synthase catalyzes the attack on C-2 of oxaloacetate by the C-2 of propionyl-CoA from the Si-face to yield (2R,3S)-methylcitrate (5, 18, 50). In contrast, Si-citrate synthase is phylogenetically unrelated to homocitrate synthase, which catalyzes the formation of homocitrate from 2-oxoglutarate and acetyl-CoA (45). Homocitrate is an intermediate in lysine biosynthesis (55) and is a structural component of the active site of nitrogenases (23). However, homocitrate synthase is related to IPMS, which catalyzes the formation of 2-isopropylmalate from 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate and acetyl-CoA. Re-citrate synthase is physiologically not only related to homocitrate synthase and IPMS, but also distantly related to (R)-citramalate synthase (24), 2-hydroxy-2-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase (10), 2-phosphinomethylmalate synthase (22, 41, 52), and pyruvate carboxytransferase 5S (19). These proteins all appear to be TIM barrel metalloenzymes and thus structurally quite different from Si-citrate synthase (39).

Most enantiozymes (enzymes specific for different enantiomers) (7), such as Si- and Re-citrate synthases, are not phylogenetically related (33). A well-studied example is l-6-hydroxy-nicotine oxidase and d-6-hydroxy-nicotine oxidase, which have completely different primary and quaternary structures (40). However, there are also exceptions, e.g., (R)- and (S)-2-hydroxypropyl-thioethanesulfonate dehydrogenases are paralogous enzymes. The two dehydrogenases are related, sharing 41% amino acid sequence similarity, and belong to the short-chain dehydrogenase-reductase superfamily of enzymes (31). Interestingly, protein enantiomers (the same sequence but synthesized from either l- or d-amino acids) show reciprocal chiral substrate specificities (35).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Max Planck Gesellschaft, the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the Niedersächsische Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur.

We thank Gary Sawers for proofreading the manuscript.

Dedicated to Wolfgang Buckel, Philipps-University, Marburg, Germany.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 30 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole, F. E., M. G. Kalyanpur, and C. M. Stevens. 1973. Absolute configuration of alpha isopropylmalate and the mechanism of its conversion to beta isopropylmalate in the biosynthesis of leucine. Biochemistry 12:3346-3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornforth, J. W. 1976. Asymmetry and enzyme action. Science 193:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornforth, J. W., J. W. Redmond, H. Eggerer, W. Buckel, and C. Gutschow. 1970. Synthesis and configurational assay of asymmetric methyl groups. Eur. J. Biochem. 14:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darley, D. J., T. Selmer, W. Clegg, R. W. Harrington, W. Buckel, and B. T. Golding. 2003. Stereocontrolled synthesis of (2R,3S)-2-methylisocitrate, a central intermediate in the methylcitrate cycle. Helve. Chimi. Acta 86:3991-3999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Carvalho, L. P., and J. S. Blanchard. 2006. Kinetic analysis of the effects of monovalent cations and divalent metals on the activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alpha-isopropylmalate synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 451:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decker, K., V. D. Dai, H. Möhler, and M. Brühmüller. 1972. d- and l-6-hydroxynicotine oxidase, enantiozymes of Arthrobacter oxidans. Z. Naturforsch. 27b:1072-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittbrenner, S., A. A. Chowdhury, and G. Gottschalk. 1969. The stereospecificity of the (R)-citrate synthase in the presence of p-chloromercuribenzoate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 36:802-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, E. A., and L. Slotin. 1940. The utilization of carbon dioxide in the synthesis of alpha-ketoglutaric acid. J. Biol. Chem. 136:301-302. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forouhar, F., M. Hussain, R. Farid, J. Benach, M. Abashidze, W. C. Edstrom, S. M. Vorobiev, R. Xiao, T. B. Acton, Z. Fu, J. J. Kim, H. M. Miziorko, G. T. Montelione, and J. F. Hunt. 2006. Crystal structures of two bacterial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyases suggest a common catalytic mechanism among a family of TIM barrel metalloenzymes cleaving carbon-carbon bonds. J. Biol. Chem. 281:7533-7545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerike, U., D. W. Hough, N. J. Russell, M. L. Dyall-Smith, and M. J. Danson. 1998. Citrate synthase and 2-methylcitrate synthase: structural, functional and evolutionary relationships. Microbiology 144:929-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottschalk, G. 1969. Partial purification and some properties of the (R)-citrate synthase from Clostridium acidi-urici. Eur. J. Biochem. 7:301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottschalk, G. 1968. The stereospecificity of the citrate synthase in sulfate-reducing and photosynthetic bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 5:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschalk, G., and H. A. Barker. 1967. Presence and stereospecificity of citrate synthase in anaerobic bacteria. Biochemistry 6:1027-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottschalk, G., and H. A. Barker. 1966. Synthesis of glutamate and citrate by Clostridium kluyveri. A new type of citrate synthase. Biochemistry 5:1125-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottschalk, G., and S. Dittbrenner. 1970. Properties of (R)-citrate synthase from Clostridium acidi-urici. Hoppe-Seyler's Z. Physiol. Chem. 351:1183-1190. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottschalk, G., S. Dittbrenner, H. Lenz, and H. Eggerer. 1972. Studies on the re-citrate synthase reaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 26:455-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimm, C., A. Evers, M. Brock, C. Maerker, G. Klebe, W. Buckel, and K. Reuter. 2003. Crystal structure of 2-methylisocitrate lyase (PrpB) from Escherichia coli and modelling of its ligand bound active centre. J. Mol. Biol. 328:609-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall, P. R., R. Zheng, L. Antony, M. Pusztai-Carey, P. R. Carey, and V. C. Yee. 2004. Transcarboxylase 5S structures: assembly and catalytic mechanism of a multienzyme complex subunit. EMBO J. 23:3621-3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson, K. R., and I. A. Rose. 1963. The absolute stereochemical course of citric acid biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 50:981-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidelberg, J. F., R. Seshadri, S. A. Haveman, C. L. Hemme, I. T. Paulsen, J. F. Kolonay, J. A. Eisen, N. Ward, B. Methe, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, S. A. Sullivan, D. Fouts, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, J. D. Peterson, T. M. Davidsen, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, D. Radune, G. Dimitrov, M. Hance, K. Tran, H. Khouri, J. Gill, T. R. Utterback, T. V. Feldblyum, J. D. Wall, G. Voordouw, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. The genome sequence of the anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough Nat. Biotechnol. 22:554-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hidaka, T., K. W. Shimotohno, T. Morishita, and H. Seto. 1999. Studies on the biosynthesis of bialaphos (SF-1293).18.2-phosphinomethylmalic acid synthase: a descendant of (R)-citrate synthase? J. Antibiot. 52:925-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoover, T. R., J. Imperial, P. W. Ludden, and V. K. Shah. 1988. Biosynthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. BioFactors 1:199-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell, D. M., H. Xu, and R. H. White. 1999. (R)-citramalate synthase in methanogenic archaea. J. Bacteriol. 181:331-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jungermann, K., R. K. Thauer, J. Wenning, and K. Decker. 1968. Confirmation of unusual stereochemistry of glutamate biosynthesis in Clostridium kluyveri. FEBS Lett. 1:74-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klinman, J. P., and I. A. Rose. 1971. Stereochemistry of the interconversions of citrate and acetate catalyzed by citrate synthase, adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase, and citrate lyase. Biochemistry 10:2267-2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohlhaw, G., T. R. Leary, and H. E. Umbarger. 1969. Alpha-isopropylmalate synthase from Salmonella typhimurium. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 244:2218-2225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koon, N., C. J. Squire, and E. N. Baker. 2004. Crystal structure of LeuA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a key enzyme in leucine biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:8295-8300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krebs, H. A. 1981. Reminiscences and reflections: in collaboration with Anne Martin. Clarendon Press Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 30.Krebs, H. A., and W. A. Johnson. 1937. The role of citric acid in intermediate metabolism in animal tissues. Enzymologia 4:148-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnakumar, A. M., B. P. Nocek, D. D. Clark, S. A. Ensign, and J. W. Peters. 2006. Structural basis for stereoselectivity in the (R)- and (S)-hydroxypropylthioethanesulfonate dehydrogenases. Biochemistry 45:8831-8840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamzin, V. S., Z. Dauter, and K. S. Wilson. 1995. How nature deals with stereoisomers. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5:830-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenz, H., W. Buckel, P. Wunderwald, G. Biedermann, V. Buschmeier, H. Eggerer, J. W. Cornforth, J. W. Redmond, and R. Mallaby. 1971. Stereochemistry of si-citrate synthase and ATP-citrate-lyase reactions. Eur. J. Biochem. 24:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milton, R. C., S. C. Milton, and S. B. Kent. 1992. Total chemical synthesis of a d-enzyme: the enantiomers of HIV-1 protease show reciprocal chiral substrate specificity. Science 256:1445-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Brien, R. W., and J. R. Stern. 1969. Reversal of the stereospecificity of the citrate synthase of Clostridium kluyveri by p-chloromercuribenzoate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 34:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogston, A. G. 1948. Interpretation of experiments on metabolic processes, using isotopic tracer elements. Nature 162:963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose, I. A., and E. L. O'Connell. 1967. Mechanism of aconitase action. I. The hydrogen transfer reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 242:1870-1879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell, R. J., J. M. Ferguson, D. W. Hough, M. J. Danson, and G. L. Taylor. 1997. The crystal structure of citrate synthase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus at 1.9 Å resolution. Biochemistry 36:9983-9994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schenk, S., and K. Decker. 1999. Horizontal gene transfer involved in the convergent evolution of the plasmid-encoded enantioselective 6-hydroxynicotine oxidases. J. Mol. Evol. 48:178-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimotohno, K. W., S. Imai, T. Murakami, and H. Seto. 1990. Purification and characterization of citrate synthase from Streptomyces hygroscopicus SF-1293 and comparison of its properties with those of 2-phosphinomethylmalic acid synthase. Agric. Biol. Chem. 54:463-470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srere, P. A., L. Gonen, and H. Brazil. 1963. Citrate condensing enzyme of pigeon breast muscle and moth flight muscle. Acta Chem. Scand. 17:S129-S134. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stern, J. R., and G. Bambers. 1966. Glutamate biosynthesis in anaerobic bacteria. I. The citrate pathways of glutamate synthesis in Clostridium kluyveri. Biochemistry 5:1113-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stern, J. R., C. S. Hegre, and G. Bambers. 1966. Glutamate biosynthesis in anaerobic bacteria. II. Stereospecificity of aconitase and citrate synthetase of Clostridium kluyveri. Biochemistry 5:1119-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tavassoli, A., J. E. Duffy, and D. W. Young. 2006. Synthesis of trimethyl (2S,3R)- and (2R,3R)-[2-2H1]-homocitrates and dimethyl (2S,3R)- and (2R,3R)-[2-2H1]-homocitrate lactones—an assay for the stereochemical outcome of the reaction catalysed both by homocitrate synthase and by the Nif-V protein. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4:569-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Textor, S., V. F. Wendisch, A. A. De Graaf, U. Müller, M. I. Linder, D. Linder, and W. Buckel. 1997. Propionate oxidation in Escherichia coli: evidence for operation of a methylcitrate cycle in bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 168:428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thauer, R. K. 1988. Citric-acid cycle, 50 years on. Modifications and an alternative pathway in anaerobic bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 176:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas, U., M. G. Kalyanpur, and C. M. Stevens. 1966. The absolute configuration of homocitric acid (2-hydroxy-1,2,4-butanetricarboxylic acid), an intermediate in lysine biosynthesis. Biochemistry 5:2513-2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomlinson, N. 1954. Carbon dioxide and acetate utilization by Clostridium kluyveri. III. A new path of glutamic acid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 209:605-609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Rooyen, J. P., L. J. Mienie, E. Erasmus, W. J. De Wet, D. Ketting, M. Duran, and S. K. Wadman. 1994. Identification of the stereoisomeric configurations of methylcitric acid produced by si-citrate synthase and methylcitrate synthase using capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 17:738-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, S. Z., D. R. Dean, J. S. Chen, and J. L. Johnson. 1991. The N-terminal and C-terminal portions of NifV are encoded by two different genes in Clostridium pasteurianum. J. Bacteriol. 173:3041-3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wohlleben, W., R. Alijah, J. Dorendorf, D. Hillemann, B. Nussbaumer, and S. Pelzer. 1992. Identification and characterization of phosphinothricin-tripeptide biosynthetic genes in Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Gene 115:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood, H. G., C. H. Werkman, A. Hemingway, and A. O. Nier. 1942. Fixation of carbon dioxide by pigeon liver in the dissimilation of pyruvic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 142:31-45. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wunderwald, P., W. Buckel, H. Lenz, V. Buschmeier, H. Eggerer, G. Gottschalk, J. W. Cornforth, J. W. Redmond, and R. Mallaby. 1971. Stereochemistry of the re-citrate-synthase reaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 24:216-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu, H., B. Andi, J. Qian, A. H. West, and P. F. Cook. 2006. The alpha-aminoadipate pathway for lysine biosynthesis in fungi. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 46:43-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.