Abstract

Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM is an industrially important strain used extensively as a probiotic culture. Tolerance of the presence of bile is an attribute important to microbial survival in the intestinal tract. A whole-genome microarray was employed to examine the effects of bile on the global transcriptional profile of this strain, with the intention of elucidating genes contributing to bile tolerance. Genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism were generally induced, while genes involved in other aspects of cellular growth were mostly repressed. A 7-kb eight-gene operon encoding a two-component regulatory system (2CRS), a transporter, an oxidoreductase, and four hypothetical proteins was significantly upregulated in the presence of bile. Deletion mutations were constructed in six genes of the operon. Transcriptional analysis of the 2CRS mutants showed that mutation of the histidine protein kinase (HPK) had no effect on the induction of the operon, whereas the mutated response regulator (RR) showed enhanced induction when the cells were exposed to bile. These results indicate that the 2CRS plays a role in bile tolerance and that the operon it resides in is negatively controlled by the RR. Mutations in the transporter, the HPK, the RR, and a hypothetical protein each resulted in loss of tolerance of bile. Mutations in genes encoding another hypothetical protein and a putative oxidoreductase resulted in significant increases in bile tolerance. This functional analysis showed that the operon encoded proteins involved in both bile tolerance and bile sensitivity.

Lactobacillus acidophilus is one of several species of bacteria that populate the human gastrointestinal tract. Some species in this group exert properties that confer health benefits on their host. L. acidophilus NCFM is an industrially important strain that has been used extensively as a probiotic culture in yogurt and dietary supplements (31). Recently, the complete genome of L. acidophilus NCFM was sequenced, leading to the elucidation of groups of genes involved in traits such as acid tolerance and adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells (2, 11, 17). Viability in the intestinal tract depends on the microorganism's ability to survive in this region, where stresses include low pH and the presence of bile.

Bile salts are one of the major components of bile and consist of a cholesterol-derived ring structure that is amide linked to an amino acid, either glycine or taurine. The amphipathic nature of conjugated bile salts allows them to act as emulsifiers that facilitate the dietary absorption of lipids, but this property also gives them the ability to emulsify the lipid membranes of bacterial cells (7). Some microbes in the gastrointestinal tract have the ability to hydrolyze this amide linkage, creating deconjugated bile salts that can damage bacterial membranes and lead to cell death (18). Some bile salts have the ability to cross lipid membranes into the cellular cytoplasm, where they can damage DNA and proteins (20, 25). Bile has been shown to induce transcription of molecular chaperones, such as GroESL, and other proteins involved in DNA and protein repair (20). While bile-specific defense mechanisms are not wholly understood, a diverse group of them have been elucidated, including those that export bile from the cell and chemically modify bile constituents (7, 27, 32, 34).

Mechanisms to sense the presence of bile and alter transcription are not well characterized but may involve a two-component regulatory system (2CRS). 2CRSs allow bacteria to sense and respond to changes in their environment after receiving an environmental signal through transmembrane sensing domains of the histidine protein kinase (HPK). Once it receives a signal input, the HPK autophosphorylates through ATP hydrolysis. The phosphoryl group is then transferred to the regulatory domain of the response regulator (RR), which in turn promotes a transcriptional response through its DNA binding domain (28). Previous studies have shown the ability of bacteria to alter the transcription of necessary genes in the presence of bile or bile constituents, including potential induction through the RR of a 2CRS (26), and have indicated the increased expression of genes in a 2CRS in response to bile (20, 30). However, to date, no system has been functionally characterized in any gram-positive organism.

The complete genome sequence of L. acidophilus NCFM allows examination of the genomic elements that confer probiotic properties on the strain (1). cDNA microarrays have proven a key tool for the examination of bacterial transcriptomes (2, 6). This study employed a whole-genome microarray representing 97.4% of the open reading frames (ORFs) to investigate how L. acidophilus NCFM reacts to the presence of bile in its environment and to identify genes that contribute to bile tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Broth cultures of Lactobacillus strains were grown anaerobically at 37°C or 42°C in MRS broth (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI). Cells were plated on MRS agar (1.5%) supplemented with chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml) and erythromycin (Em) (5 μg/ml) when appropriate for selection. Escherichia coli strains were cultivated aerobically in Luria-Bertani medium (Difco) at 37°C with 150 μg/ml Em. E. coli transformants were selected on brain heart infusion medium (Difco) with 150 μg/ml Em. Counts (CFU/ml) were performed by plating cells on agar with a Whitley Automatic Spiral Plater (Don Whitley Scientific Ltd., West Yorkshire, England). Culture growth was monitored at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) in 96-well plates using the BMG Labtech (Offenburg, Germany) FLUOstar Optima plate reader. Cultures were grown at 37°C for 23 h in a volume of 200 μl.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli EC1000 | RepA+ MC1000; Kmr; host for pORI28-based plasmids | 19 |

| L. acidophilus NCFM | Human intestinal isolate | 5 |

| L. acidophilus NCK1392 | NCFM containing pTRK669 | 29 |

| L. acidophilus NCK1871 | NCFM with a 301-bp deletion of ORF 1427 (putative oxidoreductase) | This study |

| L. acidophilus NCK1873 | NCFM with a 245-bp deletion of ORF 1428 (hypothetical protein) | This study |

| L. acidophilus NCK1875 | NCFM with a 938-bp deletion of ORF 1429 (transporter) | This study |

| L. acidophilus NCK1877 | NCFM with an 1,153-bp deletion of ORF 1430 (histidine protein kinase) | This study |

| L. acidophilus NCK1879 | NCFM with a 217-bp deletion of ORF 1431 (response regulator) | This study |

| L. acidophilus NCK1881 | NCFM with a 202-bp deletion of ORF 1432 (hypothetical protein) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pORI28 | Emrori (pWV01); replicates only with repA in trans | |

| pTRK669 | ori (pWV01) Cmr; temperature sensitive; provides repA in trans | |

| pTRK915 | 3.6 kb; pORI28 with 925- and 868-bp noncontiguous regions flanking LBA1427 | This study |

| pTKR916 | 3.4 kb; pORI28 with 904- and 862-bp noncontiguous regions flanking LBA1428 | This study |

| pTRK917 | 3.5 kb; pORI28 with 936- and 901-bp noncontiguous regions flanking LBA1429 | This study |

| pTRK918 | 3.6 kb; pORI28 with 990- and 975-bp noncontiguous regions flanking LBA1430 | This study |

| pTRK919 | 3.5 kb; pORI28 with 971- and 846-bp noncontiguous regions flanking LBA1431 | This study |

| pTRK920 | 3.5 kb; pORI28 with 870- and 943-bp noncontiguous regions flanking LBA1432 | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal L. acidophilus DNA was extracted using the method of Walker and Klaenhammer (37). Large-scale plasmid preparations for the purpose of cloning were performed using the Mo Bio UltraClean plasmid preparation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA). Smaller-scale preparations for screening and transformation were performed using the QIAprep Spin kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR primers (Tables 2 and 3) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), and PCR amplifications were carried out using a Taq polymerase PCR system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Endonuclease restriction digests were carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Digested fragments were excised from 1% agarose gels and extracted using the Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Ligations were performed using T4 DNA Ligase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer's directions and transformed into chemically competent E. coli cells. Electrocompetent L. acidophilus NCFM cells were prepared as described by Walker et al. (36). Southern hybridization of genomic DNA was carried out using Magnacharge nylon transfer membranes (MSI, Westboro, MA) according to standard protocols.

TABLE 2.

Primers used to generate gene deletions

| ORF | Downstream region | Upstream region |

|---|---|---|

| LBA1427 | Forward GATCCCATGGTCTACTCTTACCATTCTTAAC | Forward GATCCTCGAGAATCATCACGAGTAATCAC |

| Reverse GATCCTCGAGTAGCTGAAATTGCTAGTC | Reverse GATCGAATTCCTTGCACCAATTGAAGAAC | |

| LBA1428 | Forward GATCCCATGGAAAGTTGACCAATTGTAG | Forward GATCCTCGAGAATTTCTACCTTTCTTTAATG |

| Reverse GATCCTCGAGAATGGGTTATGGTAAATCAG | Reverse GATCGAATTCTTGGTTGCTGTTATTTAGAC | |

| LBA1429 | Forward GATCCCATGGCTAATTCTTGCCAAATCTG | Forward GATCCTCGAGATCAACGGATTAACAAACATAG |

| Reverse GATCCTCGAGTTTGGTCCTATGATTAGTG | Reverse GATCGAATTCTCGATTCTGGTTGTTATTTAG | |

| LBA1430 | Forward GATCCTCGAGAATTTCTGAATCATCCTTATC | Forward GATCCCATGGAAGCGCACAGTATCAAAG |

| Reverse GATCGAATTCCCTAATGGTTATCGTTCTTATC | Reverse GATCCTCGAGTGGATTAGCTATGGCTCAAG | |

| LBA1431 | Forward GATCCCATGGTATTGCCTAGCATCTCTTCC | Forward GATCCTCGAGTTTGTTTAAGAGCGGTAATTCC |

| Reverse GATCCTCGAGAGCAAGAATTAGCGAGTCAC | Reverse GATCGAATTCCTATAATGGCGTAAACGAAAG | |

| LBA1432 | Forward GATCCCATGGACACGAGTAATACCGACCAATC | Forward GATCCTCGAGTAATCTTTCTCTTTAACAATAG |

| Reverse GATCCTCGAGACGAGAATTAAAGCGGGTAG | Reverse GATCGAATTCTTGACTTAACAGGAATATC |

TABLE 3.

Primers used in RT-QPCR

| Target ORF | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBA0383 | GCAAATCCTATCAGGTAATC | ACCGTCTACTACTTTCAAC | 131 |

| LBA0406 | GCCACTTCTTCAAGAAATC | GTTGAAAGTACCACGAATC | 115 |

| LBA1247 | AGTTAAAGACGCAGTTATTAC | AGTTGGTTCGTTGATAATTC | 118 |

| LBA1425 | TGAACGATAAGGCTAACC | GCGTATTTCTTGGGAATG | 114 |

| LBA1426 | AAATTCTGATAAGCCTCAAC | GATGTAGCAGTAATAGCATAG | 123 |

| LBA1429 | CAATATCTGCTTGGGTAAC | CAGAAATGTGCCAAAGAG | 108 |

| LBA1432 | TACCCGGTCATTATTTCGTTG | ATCAGCTACCCGCTTTAATTC | 140 |

| LBA1460 | TTACACAGTCAGGTAAGAG | AATAATAACTGGGCTAGGC | 104 |

| LBA1496 | GGTCATCTTTCAACGAATC | TTGGAGGTAAGGCAATATC | 115 |

| LBA1652 | AACGGCAATATTATTTGGG | GTTACTTCAATCGTGTATGG | 131 |

Generation of the L. acidophilus NCFM microarray.

Microarrays were designed as described previously by Azcarate-Peril et al. (2). Briefly, total genomic DNA was used as a PCR template for the amplification of 1,996 predicted ORFs. PCR products were purified and spotted in triplicate onto glass slides. The arrays were assessed for quality by hybridization of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNA samples prepared from total RNA. Data from these samples revealed a linear correlation in relative expression with no more than a twofold change in expression.

cDNA probe preparation and microarray hybridization.

NCFM cells were grown to an OD600 between 0.2 and 0.3 (representing early log phase). The cells were then pelleted at room temperature and resuspended in either MRS or MRS with 0.5% (wt/vol) oxgall (Difco) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then cold shocked in an ethanol-dry ice bath, pelleted at 4°C, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen)-chloroform extraction, and residual genomic DNA was removed using DNase I, amplification grade (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's directions. The RNA concentration and quality were determined by spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis. Twenty-five micrograms of RNA were aminoallyl labeled by reverse transcription with random hexamers in the presence of aminoallyl dUTP (Sigma Chemical Co.) using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), followed by fluorescent labeling with N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated Cy3 or Cy5 ester (Amersham Biotechnology). The labeled cDNA probes were purified using a PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). Coupling of the Cy3 and Cy5 dyes to the aminoallyl-dUTP-labeled cDNA and hybridization of samples to microarrays were performed according to the protocols outlined by The Institute for Genome Research (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/microarray/protocolsTIGR.shtml). Cy5- and Cy3-labeled cDNA probes were hybridized to the arrays for 16 h at 42°C. After hybridization, the slides were washed twice in high-stringency buffer (1× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] with 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate[SDS]) for 5 min each. The first wash was performed at 42°C and the second at room temperature. The slides were then washed in a low-stringency buffer (0.1× SSC containing 0.2% SDS) for 5 min at room temperature and finally in 0.1× SSC for two 2.5-min washes at room temperature.

Data normalization and gene expression analysis.

Immediately after the slides were washed, fluorescence intensities were acquired at 10-μm resolution using a ScanArray 4000 microarray scanner (Packard Biochip BioScience; Biochip Technologies LLC) and stored as TIFF images. Signal intensities were quantified, background was subtracted, and the data were normalized using the QuantArray 3.0 software package (Perkin-Elmer). Two slides per experiment, each containing triplicate arrays, were hybridized reciprocally to Cy3- and Cy5-labeled probes (dye swapping). Spots were analyzed by adaptive quantitation. The data were median normalized. When the local background intensity was higher than the spot signal, no data were recorded for those spots. The mean of the six ratios per gene was recorded, and the ratio between the average absolute pixel values for the replicated spots of each gene, with or without treatment, represented the change in gene expression. Genes in potential operons were considered for analysis if at least one gene of the operon showed significant expression changes and the remaining genes showed trends toward that expression. Confidence intervals and P values for the change were also calculated with the use of a two-sample t test. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Site-specific integration and deletion in L. acidophilus NCFM.

Two noncontiguous fragments flanking an internal region of the target ORF were amplified using PCR primers listed in Table 2. The fragments were cloned into pORI28 and then transformed into L. acidophilus NCK1392 containing the temperature-sensitive helper plasmid pTRK669. Selection of integrants was then carried out as described previously (29). Upon successful integration of the plasmid into the genome, a single integrant colony was propagated in the absence of antibiotic selection and replica plated onto MRS agar and MRS agar containing Em. Ems cells were screened for a deletion mutation using PCR with primers flanking the targeted region, and deletions were confirmed by Southern blotting.

Bile survival assays.

To test deletion mutants for survival in the presence of bile, cells were grown to early log phase (OD600 = 0.2 to 0.3), serially diluted, and plated on MRS agar containing 0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.0% (wt/vol) oxgall (Difco) or bile salts (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) using a Whitley Automatic Spiral Plater. The concentrations of oxgall were chosen to emulate the concentrations found in the human intestinal tract, which range from 0.2 to 2% (16).

MICs of oxgall, glycocholic acid (GCA), taurocholic acid (TCA), glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), and sodium chloride were determined by spotting approximately 104 early-log-phase cells (OD600 = 0.2 to 0.3) onto MRS agar plates containing increasing concentrations of these compounds. Inhibitory concentrations of Triton X-100 and SDS (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) were determined by inoculating 200-μl MRS broth cultures containing increasing amounts of these compounds. Inhibition was reported as the lowest concentration tested that prevented the growth of the strain. The increments of concentrations tested were as follows: bile salts, 1 μg/ml; salt, 5 μg/ml (1%); TX-100, 0.5%; SDS, 0.02%.

RT-PCR and RT-QPCR.

RNA samples were collected and treated as described for microarray experiments. Reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (RT-QPCR) primers are shown in Table 3. PCR was performed using the Quanti-Tect Reverse Transcriptase PCR kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's directions, but the total reaction size was reduced to 20 μl. PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad My-IQ single-color detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Absolute mRNA copy numbers were determined using a standard curve of known concentrations, and transcripts were enumerated using the MyIQ software. Copy numbers per cell were determined by normalizing the transcript number of the queried ORF to the transcript number of LBA383 (DNA polymerase III, delta subunit).

RT-PCR was carried out to determine intergenic transcription using the Superscript II kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. cDNAs were generated using random primers. PCR was performed using primers specific to the intergenic regions of the hypothetical cotranscript.

Northern blotting.

Northern blotting of total RNA was carried out using the NorthernMax Gly kit (Ambion). Briefly, RNA was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and transferred to a Magnacharge nylon transfer membrane (MSI). The membrane was probed with a 692-bp fragment of LBA1430 labeled with [γ-32P]CTP. Transfer, hybridization, washing, and exposure to films (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY) were carried out according to standard methods and the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Differentially expressed genes.

Global gene expression patterns of bile-exposed NCFM cells were determined using microarray analysis. Table 4 lists the 289 genes that were differentially expressed (≥2-fold upregulated or downregulated) and met the criteria for statistical significance (P < 0.05). Overall, 78 genes (3.9% of the genome) were shown to be induced while 168 (8.4%) were repressed.

TABLE 4.

L. acidophilus NCFM ORFs differentially expressed upon exposure to 0.5% oxgalla

| COG functional classification, gene, and gene productb | Ratioc |

|---|---|

| C: energy production and conversion | |

| LBA0055: d-lactate dehydrogenased | 2.1 |

| LBA0466: hypothetical protein | 5.2 |

| LBA0741: acetate kinase AckB | 0.4 |

| LBA1107: glutathione reductase | 0.4 |

| LBA1109: hypothetical protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1125: manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase | 0.5 |

| LBA1418: NADH-dependent oxidoreductase | 0.4 |

| LBA1632: NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase; SsdH | 2.1 |

| D: cell division and chromosomal partitioning | |

| LBA0275: hypothetical protein | 0.3 |

| LBA0277: putative cell cycle protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1497: unknown | 2.1 |

| LBA1735: EpsC | 0.5 |

| LBA1827: chromosome-partitioning protein | 0.7 |

| E: amino acid transport and metabolism | |

| LBA0045: sugar transporterd | 2.3 |

| LBA0158: asparagine synthetase | 0.4 |

| LBA0552: multidrug transporterd | 0.4 |

| LBA0711: spermidine/putrescine ABC transporter; PotB | 0.5 |

| LBA0789: aminotransferase (NifS family) | 0.2 |

| LBA0850: aspartokinase/homoserine dehydrogenase | 0.4 |

| LBA0995: amino acid permease | 0.2 |

| LBA1177: iron-sulfur cofactor synthesis protein; YrvO | 0.3 |

| LBA1222: branched-chain amino acid permease | 0.5 |

| LBA1292: amino acid transporter | 0.3 |

| LBA1429: transporterd | 3.0 |

| LBA1446: multidrug resistance proteind | 7.3 |

| LBA1974: pyruvate oxidase | 2.6 |

| F: nucleotide transport and metabolism | |

| LBA0245: GMP synthase | 0.4 |

| LBA0953: 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide 2′-phosphodiesterase | 0.4 |

| LBA1242: adenine phosphorobosyltransferase; AprT | 0.3 |

| LBA1551: phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase; PurD | 0.5 |

| LBA1552: phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide, PurH | 0.4 |

| LBA1553: phosphoribosyl glycinamide; PurN | 0.5 |

| LBA1554: phosphoribosylformylglycinamide cycloligase; PurM | 0.4 |

| LBA1555: phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase; PurL | 0.3 |

| LBA1556: phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase; PurL | 0.3 |

| LBA1559: phosphoribosylaminoimidazole-succinocarboxamide synthetase; PurC | 0.3 |

| LBA1560: phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase; PurK | 0.5 |

| LBA1745: guanylate kinase | 0.4 |

| LBA1891: adenylosuccinate lyase | 0.5 |

| LBA1892: adenylosuccinate synthase | 0.4 |

| LBA1893: GMP reductase | 0.3 |

| G: carbohydrate transport and metabolism | |

| LBA0045: sugar transporterd | 2.3 |

| LBA0144: N-acetylglucosamine-6-P deacetylase | 2.0 |

| LBA0436: N-acetylglucosamine catabolic protein | 0.4 |

| LBA0552: multidrug transporterd | 0.4 |

| LBA0600: xylulose-5-phosphate/fructose phosphoketolase | 2.1 |

| LBA0618: cellobiose-specific PTS system IIC; PtcD | 0.5 |

| LBA0716: phosphoglucomutase | 0.5 |

| LBA1376: transmembrane protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1429: transporterd | 3.0 |

| LBA1433: dihydroxyacetone kinase | 2.3 |

| LBA1848: di/tripeptide transporter | 0.5 |

| LBA1885: hypothetical proteind | 0.5 |

| LBA1905: amino acid permease; AapA | 0.4 |

| LBA1458: galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | 3.1 |

| LBA1459: galactokinase | 4.4 |

| LBA1462: beta-galactosidase | 2.8 |

| LBA1463: lactose permease | 3.2 |

| LBA1467: beta-galactosidase large subunit | 2.9 |

| LBA1468: beta-galactosidase small subunit | 2.1 |

| LBA1643: ABC transporter permease | 0.4 |

| LBA1644: ABC transporter permease | 0.3 |

| LBA1645: multiple-sugar ABC transporter | 0.4 |

| LBA1812: alpha-glucosidase II | 3.0 |

| LBA1870: maltose phosphorylase | 4.2 |

| LBA1885: hypothetical proteind | 0.5 |

| H: coenzyme transport and metabolism | |

| LBA0055: d-lactate dehydrogenased | 2.1 |

| LBA0790: thiazole biosynthesis protein; ThiL | 0.4 |

| LBA1232: apo-citrate lyased | 0.5 |

| LBA1974: pyruvate oxidased | 2.6 |

| I: lipid metabolism | |

| LBA0948: inner membrane trans-acylase protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1167: mevalonate kinase | 0.5 |

| LBA1168: mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase | 0.4 |

| LBA1169: phosphomevalonate kinase | 0.5 |

| LBA1232: apo-citrate lyased | 0.5 |

| LBA1308: fatty acid/phospholipid synthesis protein; PlsX | 0.5 |

| LBA1447: hypothetical protein | 4.9 |

| J: translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis | |

| LBA0272: peptidyl tRNA hydrolase | 0.3 |

| LBA0280: transcriptional regulator | 0.3 |

| LBA0281: lysine tRNA synthetase; LysRS | 0.4 |

| LBA0347: glutamyl tRNA synthetase; GluRS | 0.4 |

| LBA0370: 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | 0.5 |

| LBA0417: alanyl tRNA synthetase; AlaRS | 0.4 |

| LBA0623: methionine aminopeptidase; AmpM | 0.5 |

| LBA0636: peptide chain release factor 3 | 0.3 |

| LBA0791: 16S pseudouridylate synthetase | 0.4 |

| LBA0822: tRNA methyltransferase | 0.4 |

| LBA0830: polypeptide deformylase; Pdf | 0.4 |

| LBA1178: [nucleolar protein] | 0.4 |

| LBA1446: multidrug resistance proteind | 7.3 |

| LBA1448: [alpha-galactosidase] | 2.2 |

| LBA1457: galactose-1-epimerase | 2.8 |

| LBA1518: phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase; SyfB | 0.4 |

| LBA1519: phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase; SyfA | 0.4 |

| LBA1627: [acetyltransferase] | 2.7 |

| K: transcription | |

| LBA0393: transcriptional regulator (GntR family) | 0.4 |

| LBA0516: transcriptional regulator (GntR family) | 0.4 |

| LBA1148: fibronectin-binding protein | 0.3 |

| LBA1249: heat-inducible transcription repressor; HrcA | 3.2 |

| LBA1431: response regulatord | 3.0 |

| LBA1461: hypothetical protein | 2.2 |

| LBA1517: transcription elongation factor; GreA | 0.5 |

| LBA1638: [TetR] | 3.4 |

| LBA1828: chromosome-partitioning protein | 0.4 |

| L: DNA replication, recombination, and repair | |

| LBA0273: TrcF | 0.2 |

| LBA0666: recombination protein; RecA | 0.3 |

| LBA0688: exinuclease ABC; UvrB | 0.2 |

| LBA0689: exinuclease ABC; UvrA | 0.2 |

| LBA0740: [modification methylase] | 0.3 |

| LBA0946: exinuclease ABC subunit C | 0.5 |

| LBA1077: chromosome segregation helicase | 0.3 |

| LBA1122: DNA topoisomerase IV; subunit B | 0.4 |

| LBA1123: DNA topoisomerase IV; subunit C | 0.5 |

| LBA1145: phage integrase-recombinase | 0.4 |

| LBA1243: single-stranded DNA-specific exonuclease; RecJ | 0.2 |

| LBA1420: transposase | 0.4 |

| M: cell envelope biogenesis, outer membrane | |

| LBA0018: unknown | 2.6 |

| LBA0177: autolysin; amidase | 0.5 |

| LBA0234: UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase | 0.5 |

| LBA0462: glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | 0.2 |

| LBA0514: surface layer protein | 2.4 |

| LBA0519: UDP-N-acetyl-d-mannosamine transferase | 2.2 |

| LBA0520: galactosyltransferase | 2.6 |

| LBA0625: UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | 0.5 |

| LBA0668: undecaprenyl-phosphate N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferase | 0.5 |

| LBA0708: UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvolglucosamine reductase; MurB | 0.5 |

| LBA0765: UDP-N-acetylmuramyl tripeptide synthetase | 0.3 |

| LBA0803: cell division protein; MraW | 2.2 |

| LBA1140: lysin | 0.1 |

| LBA1244: sortase; SrtA | 0.4 |

| LBA1351: lysin | 0.3 |

| LBA1733: phosphoglucosyltransferase; EpsE | 0.5 |

| LBA1736: EpsB | 0.5 |

| LBA1743: cell wall-associated hydrolase | 0.3 |

| LBA1744: [glycosidase] | 0.2 |

| LBA1757: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1758: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1829: glucose-inhibited division protein B | 0.5 |

| LBA1883: probable NLP/P60 family secreted protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1918: lysin Lj965 phage | 0.3 |

| N: cell motility and secretion | |

| LBA0176: N-acetylmuramidased | 0.4 |

| O: posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | |

| LBA0083: HtrA | 4.8 |

| LBA0283: ClcP ATPase | 0.4 |

| LBA0278: FtsH cell division protein | 0.5 |

| LBA0388: [glycoprotein endopeptidase] | 0.5 |

| LBA0390: endopeptidase | 0.5 |

| LBA0405: cochaperonin; GroES | 6.2 |

| LBA0406: chaperonin; GroEL | 6.1 |

| LBA0638: ATP-dependent Clp protease; ClpE | 5.9 |

| LBA0642: negative regulator of genetic competence; | 2.1 |

| MecA | 2.1 |

| LBA0847: ClpX | 0.3 |

| LBA0984: ATP-dependent protease; HlsV | 0.5 |

| LBA0985: ATP-dependent protease; HlsU | 0.5 |

| LBA1247: heat shock protein; DnaK | 2.7 |

| LBA1248: cochaperonin; GrpE; Hsp70 cofactor | 3.2 |

| LBA1428: hypothetical protein | 2.4 |

| LBA1910: ATP-dependent protease; ClpE | 3.9 |

| P: inorganic ion transport and metabolism | |

| LBA0045: sugar transporterd | 2.3 |

| LBA0166: K+ uptake protein | 0.4 |

| LBA0552: multidrug transporterd | 0.4 |

| LBA0641: hypothetical protein | 3.6 |

| LBA0904: outer membrane lipoprotein precursor | 0.5 |

| LBA0997: aluminum resistance protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1429: transporterd | 3.0 |

| LBA1446: multidrug resistance proteind | 7.3 |

| LBA1683: cation-transporting ATPase | 3.6 |

| Q: secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | |

| LBA0644: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1422: pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase; PnxC | 0.3 |

| R: general function prediction only | |

| LBA0045: sugar transporterd | 2.3 |

| LBA0055: d-lactate dehydrogenased | 2.1 |

| LBA0159: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA0336: thiazole monophosphate biosynthesis | 0.5 |

| LBA0342: 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase | 0.3 |

| LBA0346: DNA repair protein; RadA | 0.2 |

| LBA0392: [dehydrogenase] | 0.5 |

| LBA0552: multidrug transporterd | 0.4 |

| LBA0612: transport protein | 0.4 |

| LBA0635: transport protein | 0.4 |

| LBA0705: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA0718: hydrolase (HAD family) | 0.5 |

| LBA0828: metallo-β-lactamase superfamily protein | 0.5 |

| LBA0848: GTP-binding protein (ENGB family) | 0.3 |

| LBA0949: [metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily] | 0.5 |

| LBA0971: O-linked GlcNAc transferase | 0.4 |

| LBA0950: oxidoreductase | 0.5 |

| LBA1192: [methyltransferase] | 0.5 |

| LBA1310: dihydroxyacetone kinase | 0.4 |

| LBA1429: transporterd | 2.7 |

| LBA1446: multidrug resistance proteind | 7.3 |

| LBA1637: membrane protein | 3.8 |

| LBA1642: hypothetical protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1676: amino acid ABC transporter; permease | 0.5 |

| LBA1731: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1759: ABC transporter; ATPase | 0.5 |

| LBA1869: beta phosphoglucomutase; PgmB | 3.4 |

| LBA1885: hypothetical proteind | 0.5 |

| LBA1903: glutamine amidotransferase | 0.5 |

| LBA1943: [lipoprotein A/antigen precursor] | 0.4 |

| LBA1944: sugar ABC transporter ATPase | 0.4 |

| LBA1952: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| S: function unknown | |

| LBA0084: hypothetical protein | 3.0 |

| LBA0122: hypothetical protein | 2.3 |

| LBA0207: hypothetical protein | 0.4 |

| LBA0435: hypothetical protein | 0.4 |

| LBA0555: myosin cross-reactive antigen | 4.6 |

| LBA0624: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA0714: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA0715: hypothetical protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1010: hypothetical protein | 0.3 |

| LBA1119: [inner membrane protein] | 3.1 |

| LBA1206: hypothetical protein | 2.2 |

| LBA1339: hypothetical protein | 2.4 |

| LBA1432: hypothetical protein | 2.8 |

| LBA1628: hypothetical protein | 2.9 |

| LBA1940: hypothetical protein | 0.3 |

| T: signal transduction mechanisms | |

| LBA0722: protein-tyrosine phosphatase | 0.3 |

| LBA0746: response regulator | 0.5 |

| LBA0747: histidine kinase | 0.3 |

| LBA1430: histidine kinase | 3.0 |

| LBA1431: response regulatord | 3.0 |

| U: intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | |

| LBA0176: N-acetylmuramidased | 0.4 |

| LBA0673: preprotein translocase; SecA | 0.4 |

| LBA1290: signal recognition protein; Ffh | 0.3 |

| LBA1496: fibrinogen-binding protein | 2.5 |

| LBA1523: SpoIIIJ family protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1654: surface protein | 4.6 |

| V: defense mechanisms | |

| LBA0751: membrane protein; VanZ | 2.8 |

| LBA1006: penicillin-binding protein | 0.4 |

| LBA1132: ABC transporter; ATP binding protein | 2.0 |

| LBA1585: [ABC transporter; ATP-binding] | 0.4 |

| LBA1679: ABC transporter permease | 5.3 |

| LBA1680: ABC transporter ATPase | 3.6 |

| LBA1821: ABC transporter ATPase | 0.4 |

| LBA1822: ABC transporter ATPase | 0.3 |

| No COG | |

| LBA0019: hypothetical protein | 2.3 |

| LBA0222: unknown | 2.2 |

| LBA0493: aggregation promoting protein | 0.2 |

| LBA0512: hypothetical protein | 2.2 |

| LBA0515: hypothetical protein | 0.2 |

| LBA0695: unknown | 0.4 |

| LBA0720: unknown | 0.3 |

| LBA1426: unknown | 2.1 |

| LBA1460: mucus binding protein precursor | 2.7 |

| LBA1612: fibrinogen-binding protein | 0.5 |

| LBA1747: unknown | 0.5 |

| LBA1852: [d-Ala ligase] | 2.0 |

Array ratios from three biological replicates and three technical replicates were averaged.

Genes were classified according to the COG domain present in the encoded protein sequence.

Ratio indicates relative mRNA ratio (0.5% oxgall/0% oxgall).

ORF present in more than one COG.

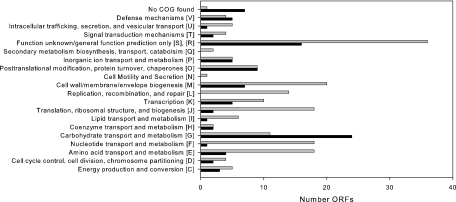

While the expression of the majority of genes in the genome did not change significantly, patterns of expression emerged across cluster of orthologous groups (COG) classifications (Fig. 1) (33). Most differentially expressed ORFs involved in metabolism of proteins, nucleotides, and lipids were downregulated in the presence of bile, including tRNA synthetases for several amino acids, and the operon involved in purine biosynthesis (LBA1551 to LBA1560). Because of the repression of these groups of genes, growth of NCFM was monitored in the presence and absence of 0.5% oxgall. The maximum specific growth rate of cells in 0.5% oxgall was reduced 25% compared to that of cells grown in MRS (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of ORFs within COG classifications. The black bars represent the numbers of upregulated ORFs (total, 78), and the gray bars represent downregulated ORFs (total, 168).

The COG with the most genes upregulated contained those involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism, including the lactose and galactose operons. Interestingly, the genes in these operons were induced in the presence of bile despite the catabolite repression effects afforded by the 2% (wt/vol) glucose present in MRS (6). Also upregulated were several general stress response genes, in agreement with induction data from other species (20, 27, 30). Finally, microarray analysis indicated the upregulation of some genes potentially involved in bacterial adhesion to intestinal cells, including LBA1460, a mucus binding protein precursor, and LBA1496, a putative fibrinogen binding protein. Upregulation of several stress response and adhesion genes was confirmed using RT-QPCR. Expression of LBA1652, annotated as a mucus binding protein precursor, was analyzed using RT-QPCR and found to be upregulated almost 11-fold.

Among genes not differentially expressed upon exposure to bile were the two bile salt hydrolases characterized previously. In some species, including Listeria monocytogenes and Lactobacillus plantarum, these genes have been shown to play a role in bile tolerance. In L. acidophilus NCFM, knockout mutations of the two bsh genes showed no differences in survival in the presence of bile, despite encoding active enzymes that are able to deconjugate the specific bile salts GCA, GDCA, TCA, and TDCA, as well as glycochenodeoxycholic acid and taurochenodeoxycholic acid (24).

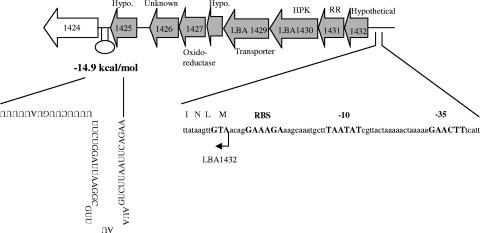

Operon configuration and annotations.

A cluster of genes seemingly unrelated by function (LBA1425 to LBA1432) was significantly induced in the presence of bile, as indicated by the microarray experiments (ranging from 2.1- to 3.0-fold upregulation). To date, this group of genes has not been shown to be differentially expressed under any test conditions examined (2, 3, 6). This cluster was particularly interesting because it contained genes for a type IIIA HPK (LBA1430) and an RR of the OmpR family (LBA1431), both with uncharacterized functions (1). Its induction in the presence of bile indicated that this 2CRS may potentially regulate transcription under these conditions. LBA1425 and LBA1426 were annotated as a hypothetical protein and an unknown protein, respectively. Neither protein contained a COG that could give a clue to its function, although BLAST analysis showed that LBA1425 had 46% identity to a putative cell surface hydrolase in L. plantarum WCFS1. LBA1427 was annotated as a putative oxidoreductase but showed less than 30% similarity to oxidoreductases from other species. It had similarity to COG0656, aldo/keto reductases (E value, 4e−11). LBA1428 showed homology (58% identity) to a predicted hypothetical protein in Lactobacillus gasseri, and it contained similarity to a COG of predicted redox proteins (E value, 3e−5). LBA1429 was annotated as a transporter based on its similarity to the major facilitator superfamily COG. This protein showed homology to a multidrug transport protein (L. plantarum WCFS1; 46% identity). LBA1432, a hypothetical protein, showed similarity to the RelA/SpoT COG (E value, 5e−21); however, this protein showed stronger similarity to COG2357, an uncharacterized protein domain of unknown function conserved in bacteria.

Because of their upregulation in the presence of oxgall and their physical proximity in the genome, ORFs LBA1425 to LBA1432 were analyzed as a potential cotranscript. Clone Manager Software (Scientific and Educational Software, Cary, NC) revealed a region of dyad symmetry downstream of LBA1425 with a Gibbs free-energy value of −14.9 kcal/mol, followed closely by a T-rich region (Fig. 2). According to de Hoon et al. (13), this free-energy value falls below the average predicted free-energy value for terminators in NCFM (−13.8 kcal/mol), indicating good potential for the area to form a rho-independent terminator in an RNA transcript. RT-PCR and Northern analysis were employed to functionally determine the length of transcription in this region. These experiments indicated that the cotranscription of genes in the region extended from LBA1432 through LBA1425, for an overall transcript length of 7 kb.

FIG. 2.

Organization of a bile-induced operon in L. acidophilus NCFM. The nucleotide sequence of the upstream promoter is shown, with the ribosomal binding site and −10 and −35 boxes in boldface type. Predicted rho-independent terminators are shown with the predicted free energy of folding. ORFs upregulated in the presence of bile are shown in gray. Putative annotations for each ORF are shown. Hypo., hypothetical.

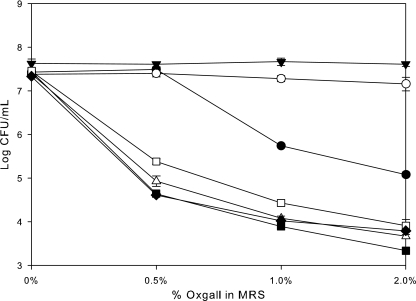

Mutant phenotypes.

In order to investigate the roles of LBA1427 to LBA1432 in bile tolerance, deletion mutant strains were generated by excising internal fragments from each of the ORFs. There were no differences in morphology or growth rate in MRS between these mutant strains and the wild type (data not shown). Survival analysis of the strains in the presence of increasing concentrations of bile showed that the survival of four of the six mutant strains (those with mutations in LBA1429, -1430, -1431, and -1432) was significantly reduced compared to the wild type (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, two of the strains (LBA1427 and LBA1428 mutants) showed increased survival in the presence of bile.

FIG. 3.

Survival of early-log-phase L. acidophilus NCFM (•), NCK 1871 (ΔLBA1427; oxidoreductase) (○), NCK 1873 (ΔLBA1428; hypothetical) (▾), NCK 1875 (ΔLBA1429; transporter) (▵), NCK 1877 (ΔLBA1430; HPK) (▪), NCK1879 (ΔLBA1431; RR) (□), and NCK 1881 (ΔLBA1432; hypothetical) (⧫) on MRS agar plates with increasing concentrations of oxgall. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean for triplicate counts.

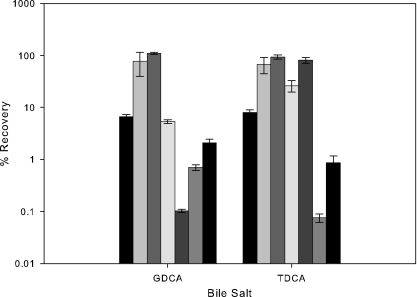

As bile salts are major constituents of bile and are able to inhibit growth in lactobacilli and bifidobacteria (18), the survival of these strains was examined in the presence of 0.2% GDCA and 0.2% TDCA (Fig. 4). Survival was also examined in the presence of 0.2% GCA and TCA, but no differences between strains were seen. Again, strains with deletions in LBA1427 (oxidoreductase) and LBA1428 (hypothetical) showed increased recovery compared to the wild type. The LBA1432 mutant (hypothetical) showed slightly less recovery than the wild type in both salts. Strains with mutations in LBA1430 (HPK) or LBA1431 (RR) showed reduced recovery on GDCA, whereas on TDCA, the RR mutant strain showed dramatically reduced recovery. Unexpectedly, the HPK mutant was not sensitive to TDCA.

FIG. 4.

Percent recovery of early-log-phase cells on MRS agar supplemented with 0.2% GDCA and TDCA compared to MRS agar. Bars (left to right): L. acidophilus NCFM, NCK 1871 (ΔLBA1427; oxidoreductase), NCK 1873 (ΔLBA1428; hypothetical), NCK 1875 (ΔLBA1429; transporter), NCK 1877 (ΔLBA1430; HPK), NCK1879 (ΔLBA1431; RR), and NCK 1881 (ΔLBA1432; hypothetical). The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean for triplicate counts.

The growth of the mutant strains was analyzed in a variety of inhibitory compounds, including four bile salts (Table 5). Generally, glycoconjugated bile salts were more inhibitory at lower concentrations than tauroconjugated salts. The RR mutant was the most sensitive overall to bile salts, while among the mutant strains, the LBA1427 (oxidoreductase) and LBA1428 (hypothetical) mutants were the least sensitive. The LBA1429 mutant strain (transporter) was more inhibited by cholic acid-based bile salts, but not deoxycholic acid-based salts, detergents, or NaCl. Growth of the HPK mutant was inhibited at slightly lower concentrations of Triton X-100, SDS, and NaCl than that of the wild-type strain.

TABLE 5.

Inhibitory concentrations of selected compounds on three independent cultures of L. acidophilus NCFM strains

| Strain | GCA (μg/ml) | TCA (μg/ml) | GDCA (μg/ml) | TDCA (μg/ml) | TX-100 (% [vol/vol]) | SDS (% [wt/vol]) | NaCl (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCFM | >9 | >15 | 6 | 10 | 2.5 | 0.07 | 30 |

| NCK1871 (oxidoreductase) | 9 | 7 | 6 | >10 | 2.5 | 0.07 | 30 |

| NCK1873 (hypothetical) | 9 | 13 | 6 | >10 | 2.5 | 0.07 | 30 |

| NCK1875 (transporter) | 4 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 2.5 | 0.07 | 30 |

| NCK1877 (HPK) | 9 | >15 | 4 | 10 | 1.0 | 0.05 | 25 |

| NCK1879 (RR) | 4 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 2.0 | 0.07 | 30 |

| NCK1881 (hypothetical) | 4 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 1.5 | 0.07 | 25 |

Role of the 2CRS in operon transcription.

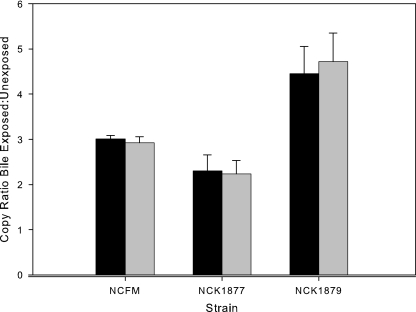

Expression of the LBA1425-LBA1432 operon was analyzed by RT-QPCR in NCFM and both the HPK and RR mutants. Expression of the gene immediately upstream (LBA1432; hypothetical) and the gene immediately downstream (LBA1429; transporter) of the 2CRS was monitored. While induction of the operon in the presence of bile was not affected by the HPK mutation, the RR mutation led to a significant increase in induction (Fig. 5). In the absence of bile, transcription of LBA1429 and LBA1432 in both mutant strains was not significantly different from that in the wild type, as determined by analysis of variance (SAS, Cary, NC) (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effects of 2CRS gene mutations on induction of LBA1429 (black bars) and LBA1432 (gray bars) in the presence of 0.5% oxgall. The error bars represent standard errors of the mean for four biological replicates.

DISCUSSION

Bile tolerance is an important aspect of survival for bacteria that habitat the intestinal tract. Examination of the transcriptome of L. acidophilus NCFM in the presence of bile showed the induction of 3.9% of the genome, including a previously uncharacterized eight-gene operon containing a 2CRS. Mutations of the HPK and RR genes led to a substantial decrease in recovery on MRS agar containing oxgall. Also within the operon, mutation of a transporter gene and a gene encoding a hypothetical protein led to decreased recovery in the presence of bile. Outside this operon, genes involved in general stress resistance, carbohydrate metabolism, and adhesion were significantly affected by the presence of bile in the cellular environment.

Analysis of a previously uncharacterized operon upregulated in the presence of bile suggested that the 2CRS within it was concerned with induction of genes involved in response to bile. HPKs and RRs that are in close proximity typically act together in sensing and regulatory capacities. Analysis of these mutant strains on oxgall plates initially indicated that this 2CRS was no exception, with both the HPK and RR deletion mutant strains showing a marked decrease in recovery in the presence of increasing levels of oxgall. The increased survival and increased growth in the presence of the specific bile salt TDCA seen in the HPK mutant strain were surprising.

Some 2CRSs control their own expression, so the transcriptional effects of mutating the HPK and the RR were examined on genes in the operon in the presence and absence of oxgall. Mutation in the RR led to an enhanced level of induction, indicating that the RR acts in the capacity of a repressor of this operon. Since the majority of the differentially regulated genes in the genome (Fig. 1) were repressed in the presence of bile, the role of this RR in the bile transcriptome could be substantial. Mutation in the HPK had no effect on induction of the operon in the presence of bile. This observation, along with the differences in phenotype between the HPK and RR mutant strains, raises two possibilities regarding this 2CRS. The first is that these two proteins do not form a cognate 2CRS but that they interact with other 2CRS components in the genome to promote a transcriptional response. Through comparative analysis, Grebe and Stock (15) demonstrated a correlation between the sequence subfamilies of HPKs and RRs that were known to act cognately. Previous analysis of the 2CRS of NCFM (1) showed that LBA1430 is a type IIIA HPK. LBA1431 belongs to the OmpR subfamily of RRs, which type IIIA HPKs have been shown to interact with exclusively. The second possibility regarding this 2CRS is that the RR is activated independently of phosphorylation by its cognate HPK. There are several reports of 2CRSs in which acetyl phosphate acts as a phospho-donor to the RR in the absence of the HPK or where the HPK and acetyl phosphate act synergistically to promote activation (4, 12, 22, 23, 38). The biological purpose for this alternative activation is uncertain, but it has been shown to play a role in transcriptional control during acid stress (4). Since there are no orphan HPK genes present in the genome that might indicate RR cross talk, and sequence analysis indicates the high probability that LBA1430 and LBA1431 form a cognate 2CRS, it is likely that this RR was activated by another phosphate-donating member, such as acetyl phosphate, in the absence of its HPK. Since deletion of the HPK did result in a decrease in survival in the presence of oxgall, it is most likely that this protein does play a role in signal transduction. Also, since the 2CRS within the operon does not act to induce it in the presence of bile, this single system is most likely a player in a more complex regulatory network that controls bile-influenced transcription. Experiments to examine the global transcriptional effects of both the HPK and the RR mutations in the presence of bile are in progress.

In addition to the 2CRS, other genes were functionally shown to play a role in bile tolerance. Decreased survival of the LBA1429 mutant in bile and growth inhibition by the cholic acid-based bile salts, but not salt or detergents, supports the hypothesis that this transporter interacts with bile salts. Transport proteins, including those belonging to the major facilitator superfamily, have been shown to act in bile salt transport in other species, including E. coli, L. monocytogenes, L. plantarum, and Eubacterium sp. (14, 21, 32, 34). Such transporters have been shown to act in various capacities in species, including influx, efflux, and antiport, and are believed to both import salts for modification and export them to prevent their deleterious effects. The differences in the roles of the transporters can lead to varying effects of mutations on bile tolerance. The exact role that LBA1429 plays is unclear from these experiments, although the LBA1429 mutant strain's lowered growth inhibition on GCA and TCA suggest interaction with cholic acid. These experiments introduce the first transporter gene in NCFM that has been implicated in bile tolerance. Sequence analysis of hypothetical protein LBA1432 does not suggest a role that it plays in bile tolerance, although weak similarity to RelA/SpoT domains might suggest that the protein is associated with gene regulation in times of stress or starvation (10). Increased recovery of LBA1427 (oxidoreductase) and LBA1428 (hypothetical) mutant strains in the presence of bile, compared to the wild type, was surprising considering that these genes are members of an operon induced by bile. Since both proteins contain homology to oxidoreductases, they could play a role in bile salt modification, as it is known that some species of intestinal bacteria possess the ability to modify bile salts through oxidation and reduction (7, 9). These proteins may act as previously unrecognized bile salt modifiers, although a role for modifiers of this type in bile tolerance or sensitivity has not been established. Many bacterial interactions with bile, such as those that lead to modification of bile salts, are poorly understood. It is possible that these proteins play an important role with bile in the gastrointestinal system but that any effects cannot be observed in vitro. Induction of the operon, along with the repression by LBA1431 (RR), could indicate a need for fine control of these genes and suggest that these proteins provide a necessary benefit to the cell.

Other findings from the microarray experiments showed upregulation of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism but downregulation of genes involved in many other aspects of growth, indicating that bile slows growth in the cells. The induction of the lactose and galactose operons was an intriguing finding, as this strain is widely utilized in yogurt and other fermented dairy products. It might be speculated that as some lactobacilli evolved in the small intestines of mammals, a frequently encountered energy source was lactose from milk. In the gastrointestinal tract, bile may act as an environmental signal for the cells to increase production of proteins needed to metabolize this energy source. This finding could suggest that consumption of this Lactobacillus strain in dairy foods might promote survival in the gastrointestinal tract, as it is better prepared to metabolize those available carbohydrates.

Bile induction of potential adhesion genes was also identified by microarray experiments and confirmed using RT-QPCR. Adhesion of bacterial cells to intestinal cells is considered an important attribute for lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract (8, 35). Induction of such adhesion determinants suggests that bile may act to signal arrival in the intestinal tract. While bile's effect on bacterial cells has been indicated as largely detrimental, induction of these genes could indicate a new role for bile as a location indicator in the cellular environment.

Examination of the global transcriptional effects of bile led to the discovery of an inducible operon that encodes proteins involved in both bile tolerance and, surprisingly, sensitivity. This duality illustrates the complexity of transcriptional regulation and reflects how little bile tolerance is currently understood. A 2CRS that aids bile tolerance is a new finding. The fact that L. acidophilus NCFM utilizes one of its nine 2CRSs in bile tolerance shows the importance of this characteristic in species that travel through the intestinal tract.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Southeast Dairy Foods Research Center; Dairy Management, Inc.; and Danisco USA, Inc. E.A.P. was supported by a Department of Education Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need Biotechnology Fellowship and a George H. Hitchings New Investigator Award in Health Sciences.

We thank E. Durmaz, M. Miller, T. Duong, and P. Ruse for their helpful discussions and technical advice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altermann, E., W. M. Russell, M. A. Azcarate-Peril, R. Barrangou, B. L. Buck, O. McAuliffe, N. Souther, A. Dobson, T. Duong, M. Callanan, S. Lick, A. Hamrick, R. Cano, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2005. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3906-3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azcarate-Peril, M. A., O. McAuliffe, E. Altermann, S. Lick, W. M. Russell, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2005. Microarray analysis of a two-component regulatory system involved in acid resistance and proteolytic activity in Lactobacillus acidophilus Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5794-5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azcarate-Peril, M. A., J. M. Bruno-Barcena, H. M. Hassan, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2006. Transcriptional and functional analysis of oxalyl-coenzyme A (CoA) decarboxylase and formyl-CoA transferase genes from Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1891-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang, I. S., J. P. Audia, Y. K. Park, and J. W. Foster. 2002. Autoinduction of the ompR response regulator by acid shock and control of the Salmonella enterica acid tolerance response. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1235-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barefoot, S. F., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1983. Detection and activity of lactacin B, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:1808-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrangou, R., M. A. Azcarate-Peril, T. Duong, S. B. Conners, R. M. Kelly, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2006. Global analysis of carbohydrate utilization by Lactobacillus acidophilus using cDNA microarrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:3816-3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begley, M., C. G. M. Gahan, and C. Hill. 2005. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:625-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernet, M., D. Brassart, J. Neeser, and A. Servin. 1994. Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 1 binds to cultured human intestinal cell lines and inhibits cell attachment and cell invasion by enterovirulent bacteria. Gut 35:483-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bortolini, O., A. Medici, and S. Poli. 1997. Biotransformations on steroid nucleus of bile acids. Steroids 62:564-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braeken, K., M. Moris, R. Daniels, J. Vanderleyden, and J. Michiels. 2006. New horizons for (p)ppGpp in bacterial and plant physiology. Trends Microbiol. 14:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buck, B. L., E. Altermann, T. Svingerud, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2005. Functional analysis of putative adhesion factors in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8344-8351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton, T. L., and J. R. Scott. 2004. CovS inactivates CovR and is required for growth under conditions of general stress in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 186:3928-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Hoon, M. J. L., Y. Makita, K. Nakai, and S. Miyano. 2005. Prediction of transcriptional terminators in Bacillus subtilis and related species. PLoS Comp. Biol. 1:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkins, C., and D. Savage. 2003. CbsT2 from Lactobacillus johnsonii 100-100 is a transport protein of the major facilitator superfamily that facilitates bile acid antiport. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6:76-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grebe, T. W., and J. B. Stock. 1999. The histidine protein kinase superfamily. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 41:139-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunn, J. S. 2000. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance and response to bile. Microbes Infect. 2:907-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaenhammer, T. R., R. Barrangou, B. L. Buck, M. A. Azcarate-Peril, and E. Altermann. 2005. Genomic features of lactic acid bacteria affecting bioprocessing and health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:393-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurdi, P., K. Kawanishi, K. Mizutani, and A. Yokota. 2006. Mechanism of growth inhibition by free bile acids in lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 188:1979-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law, J., G. Buist, A. Haandrikman, J. Kok, G. Venema, and K. Leenhouts. 1995. A system to generate chromosomal mutations in Lactococcus lactis which allow fast analysis of targeted genes. J. Bacteriol. 177:7011-7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leverrier, P., D. Dimova, V. Pichereau, Y. Auffray, P. Boyaval, and G. Jan. 2003. Susceptibility and adaptive response to bile salts in Propionibacterium freudenreichii: physiological and proteomic analysis. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 69:3809-3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallonee, D., and P. Hylemon. 1996. Sequencing and expression of a gene encoding a bile acid transporter from Eubacterium sp. strain VPI 12708. J. Bacteriol. 178:7053-7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandin, P., H. Fsihi, O. Dussurget, M. Vergassola, E. Milohanic, A. Toledo-Arana, I. Lasa, J. Johansson, and P. Cossart. 2005. VirR, a response regulator critical for Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1367-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsubara, M., and T. Mizuno. 1999. EnvZ-independent phosphotransfer signaling pathway of the OmpR-mediated osmoregulatory expression of OmpC and OmpF in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:408-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAuliffe, O., R. J. Cano, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2005. Genetic analysis of two bile salt hydrolase activities in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4925-4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prieto, A. I., F. Ramos-Morales, and J. Casadesus. 2004. Bile-induced DNA damage in Salmonella enterica. Genetics 168:1787-1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raphael, B. H., S. Pereira, G. A. Flom, Q. Zhang, J. M. Ketley, and M. E. Konkel. 2005. The Campylobacter jejuni response regulator, CbrR, modulates sodium deoxycholate resistance and chicken colonization. J. Bacteriol. 187:3662-3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rince, A., Y. Le Breton, N. Verneuil, J.-C. Giard, A. Hartke, and Y. Auffray. 2003. Physiological and molecular aspects of bile salt response in Enterococcus faecalis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 88:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson, V. L., D. R. Buckler, and A. M. Stock. 2000. A tale of two components: a novel kinase and a regulatory switch. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:626-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell, W. M., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2001. Efficient system for directed integration into the Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus gasseri chromosomes via homologous recombination. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 67:4361-4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez, B., M.-C. Champomier-Verges, P. Anglade, F. Baraige, C. G. de los Reyes-Gavilan, A. Margolles, and M. Zagorec. 2005. Proteomic analysis of global changes in protein expression during bile salt exposure of Bifidobacterium longum NCIMB 8809. J. Bacteriol. 187:5799-5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders, M. E., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2001. The scientific basis of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM functionality as a probiotic. J. Dairy Sci. 84:319-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sleator, R. D., H. H. Wemekamp-Kamphuis, C. G. Gahan, T. Abee, and C. Hill. 2005. A PrfA-regulated bile exclusion system (BilE) is a novel virulence factor in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1183-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tatusov, R. L., E. V. Koonin, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278:631-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanassi, D. G., L. W. Cheng, and H. Nikaido. 1997. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:2512-2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valeur, N., P. Engel, N. Carbajal, E. Connolly, and K. Ladefoged. 2004. Colonization and immunomodulation by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1176-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker, D. C., K. Aoyama, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1996. Electrotransformation of Lactobacillus acidophilus group A1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 138:233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker, D. C., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1994. Isolation of a novel IS3 group insertion element and construction of an integration vector for Lactobacillus spp. J. Bacteriol. 176:5330-5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfe, A. J. 2005. The acetate switch. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]