Abstract

To understand key processes governing defense mechanisms in poplar (Populus spp.) upon infection with the rust fungus Melampsora larici-populina, we used combined histological and molecular techniques to describe the infection of Populus trichocarpa × Populus deltoides ‘Beaupré’ leaves by compatible and incompatible fungal strains. Striking differences in host-tissue infection were observed after 48-h postinoculation (hpi) between compatible and incompatible interactions. No reactive oxygen species production could be detected at infection sites, while a strong accumulation of monolignols occurred in the incompatible interaction after 48 hpi, indicating a late plant response once the fungus already penetrated host cells to form haustorial infection structures. P. trichocarpa whole-genome expression oligoarrays and sequencing of cDNAs were used to determine changes in gene expression in both interactions at 48 hpi. Temporal expression profiling of infection-regulated transcripts was further compared by cDNA arrays and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Among 1,730 significantly differentially expressed transcripts in the incompatible interaction, 150 showed an increase in concentration ≥3-fold, whereas 62 were decreased by ≥3-fold. Regulated transcripts corresponded to known genes targeted by R genes in plant pathosystems, such as inositol-3-P synthase, glutathione S-transferases, and pathogenesis-related proteins. However, the transcript showing the highest rust-induced up-regulation encodes a putative secreted protein with no known function. In contrast, only a few transcripts showed an altered expression in the compatible interaction, suggesting a delay in defense response between incompatible and compatible interactions in poplar. This comprehensive analysis of early molecular responses of poplar to M. larici-populina infection identified key genes that likely contain the fungus proliferation in planta.

Plants respond to microbial invasion by activating an array of inducible defense mechanisms (Nimchuk et al., 2003). After specific recognition of a pathogen, the hypersensitive response (HR) is a rapid and efficient plant resistance mechanism leading to cell death at the site of infection (Heath, 2000). Among the rapid defense mechanisms triggered in plant tissues are generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) at the site of infection, cell wall thickening, and production of anti-microbial compounds and enzyme inhibitors (Glazebrook, 2005). Genes encoding pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins such as glucanases and chitinases are primary target genes triggered during the early response to pathogen attack (Van Loon and Van Strien, 1999) and are considered as a signature of the HR. Their expression could be directly targeted by pathogen-sensing systems through highly complex and interconnected networks of transduction pathways driving plant resistance (Katagiri, 2004). Several signal molecules, such as ethylene, salicylic acid (SA), or jasmonic acid, play an important role in these defense reaction-signaling networks (Shah, 2003), and recently a central role for the NONEXPRESSOR OF PR GENES1 (NPR1) protein has been highlighted (Dong, 2004). Considerable advances have been made in understanding plant resistance processes in the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), particularly through extensive mutant analyses. It is now clear that the plant response to pathogen infection is associated with massive changes in gene expression (Schenk et al., 2000). Large-scale mRNA expression profilings have revealed that plants express similar sets of defense mechanisms in response to different pathogens (Tao et al., 2003; Eulgem, 2004). Dissection of the defense response at the molecular level has greatly helped in drawing a general model for pathogen resistance in plants (Nimchuk et al., 2003; Tao et al., 2003). However, it is not known whether such a model applies to long-term adaptation of resistance mechanisms in perennial plant species like trees. Such long-lived species are more prone to attacks by pathogens before reproduction, and their long generation time makes it impossible for them to match the evolutionary rates of a pathogen that goes through several generations every year. Annotation of the Populus trichocarpa genome has revealed an expansion of the NBS-Leu-rich repeat (LRR) resistance gene families (Tuskan et al., 2006), suggesting a possible adaptation to long-term exposure to pathogens.

The basidiomycete Melampsora larici-populina is responsible for the leaf rust disease in Populus species (Frey et al., 2005; Pinon and Frey, 2005). Urediniospore germlings of this obligate biotrophic fungus usually penetrate the host plant through stomatal openings, differentiate a series of infection structures in the intercellular space, and exhibit highly localized penetration of the host cell wall to establish a haustorium (Laurans and Pilate, 1999). Hyphae then proliferate in the leaf parenchyma and produce golden pustules filled with masses of urediniospores on the lower leaf surface. M. larici-populina causes severe economic losses in European poplar plantations and has been recently detected in North America (Newcombe and Chastagner, 1993). Selection for resistance to this biotrophic pathogen is thus an important challenge for poplar breeders (Dowkiw and Bastien, 2004). Severe damage occurs through decreased photosynthesis efficiency, early defoliation, and increased susceptibility to other pests and diseases (Gérard et al., 2006). To date, no resistant poplar cultivars are available, as new virulent strains of M. larici-populina are developing regularly. Sustainability of newly selected resistance requires a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying Populus-Melampsora interactions. Most of the knowledge on lifestyle of fungal pathogens derives from studies in nonobligate biotrophs, and there are limited data about obligate biotrophs, such as rust fungi and powdery mildews. These fungi show a high level of compatibility with their host, but the reasons for the obligate biotroph status remains unknown (Mendgen and Hahn, 2002). To date, only sparse molecular data were obtained on defense mechanisms in poplar, and published data concern interactions with herbivores or viruses (Christopher et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2004; Major and Constabel, 2006; Ralph et al., 2006a). Molecular responses to Melampsora spp. invasion are unknown.

Here, we investigated the interaction between an interamerican hybrid poplar, P. trichocarpa × Populus deltoides ‘Beaupré’ and M. larici-populina. This poplar hybrid has been largely used in commercial poplar cultivation in Europe and harbors a qualitative resistance to M. larici-populina (Pinon and Frey, 2005). It is derived from a cross between P. trichocarpa, a species for which the genome sequence is available (Tuskan et al., 2006), and P. deltoides, a species from which rust resistance loci are inherited (Jorge et al., 2005). Efforts had been made to localize rust resistance-related genes in poplar pedigrees through genetic approaches (Cervera et al., 2004). Different studies successfully mapped rust-resistance quantitative trait loci in P. trichocarpa and P. deltoides (Lescot et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2004). To characterize the specific host-response to either virulent or avirulent strains of M. larici-populina, we carried out a combined molecular and histological analysis of time-course infection through scanning electron microscopy and quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect rust progression in planta. We also investigated lignin and ROS production in plant tissue to determine major differences in plant response between the compatible and incompatible interactions. Then, rust-responsive genes were identified using either a suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH)-cDNA library of poplar leaves infected by the avirulent M. larici-populina strain or NimbleGen whole-genome expression arrays. Finally, expression profiles of Populus defense-related genes during the time course of infection were confirmed with additional transcriptome-based approaches (reverse transcription [RT]-qPCR and cDNA arrays).

RESULTS

Time Course of Compatible and Incompatible Interactions

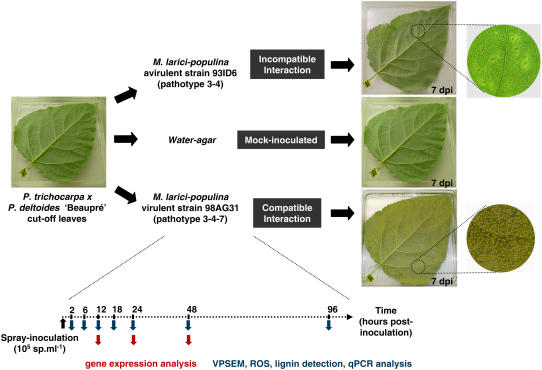

Rust development in P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ leaves was monitored at the macroscopic and microscopic levels over a period of 10 d postinoculation (dpi) with either compatible (98AG31; pathotype 3-4-7) or incompatible (93ID6; pathotype 3-4) strains of M. larici-populina. In the compatible interaction, uredinia formation was visible under the abaxial epidermis 5 dpi, and by 6 to 7 dpi, uredinia emerged through the epidermis and formed orange pustules of 1- to 2-mm diameter (Fig. 1). Uredinia distribution was uniform on the leaf surface, and there were about 73 ± 6 pustules/cm2. In the incompatible interaction (93ID6), no lesion or pustule was observed on the leaf surface over a period of 10 d. The abaxial epidermis showed very localized necrotic zones, and dark dots inside mesophyll tissues were visible in transparency after 6 dpi (Fig. 1). Control leaves inoculated with water showed no pustules or necrotic lesions after 10 d.

Figure 1.

Experimental design of time-course infection of detached leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ mock inoculated with water or inoculated with incompatible (avirulent, 93ID6) and compatible (virulent, 98AG31) strains of M. larici-populina. RNA was sampled in independent replicate experiments at 12, 24, and 48 hpi and were used for transcript profiling. Leaf tissues were also sampled at 2, 6, 12, 18, 24, 48, and 96 hpi and were then used for observation in the VPSEM, detection of ROS and lignin synthesis, and qPCR detection of pathogen growth in planta. Expression of disease (uredinia formation on abaxial epidermis) or resistance (localized hypersensitive reaction) was observed at 7 dpi. Necrotic lesions or uredinia on abaxial epidermis of foliar discs are shown at 7 dpi for the incompatible or the compatible interaction, respectively.

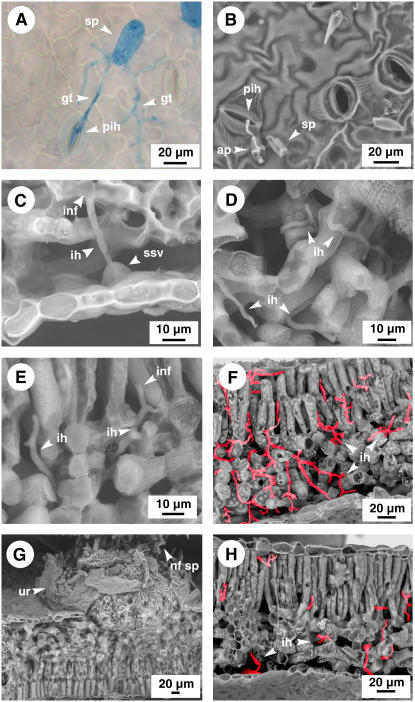

Infection structures developed by M. larici-populina at the leaf surface were monitored by aniline blue staining and light microscopy. Compatible and incompatible spores of M. larici-populina germinated within 2 h postinoculation (hpi) and germ tubes of different length (1 μm–1 mm) were observed on the leaf surface (Fig. 2A). Most of the germ tubes ramified, formed appressoria, and had successfully penetrated plant tissues at 2 hpi. Low-temperature variable pressure scanning electron microscopy (VPSEM) was used to follow in planta colonization of M. larici-populina by direct observations of infected leaf sections. Fungal structures on the leaf surface were similar to those observed with aniline blue staining for both interactions. Penetration through stomata occurred for about one-half of the successful events of germination between 2 and 6 hpi (Fig. 2B). At 6 and 12 hpi, substomatal vesicles were observed in the substomatal chambers (Fig. 2C), and infection hyphae were developing in the mesophyll tissue from these vesicles. At 18 and 24 hpi, infection hyphae extended into the mesophyll and in some cases reached the palisadic mesophyll (Fig. 2, D and E). The infection hyphae terminated their growth on a mesophyll cell forming haustorial mother cells, while other infection hyphae continued their course into the mesophyll after branching (Fig. 2, D and E). Infection structures inside the cells (i.e. haustoria) cannot be observed using VPSEM. Most of the compatible strain hyphae observed by VPSEM invaded both the spongy and the palisadic mesophyll by 48 hpi. The number of infection hyphae dramatically increased for the compatible strain at 96 hpi (Fig. 2F). Observations were further made at 5 and 7 dpi. In the compatible interaction, hyphae totally invaded the plant tissue around primary infection sites at 5 dpi, domes were formed in the spongy mesophyll, and spore-forming cells were differentiating (data not shown). By 7 dpi, domes corresponding to uredinial pustules released spores on the leaf abaxial surface (Fig. 2G). In the case of the incompatible interaction, the number of hyphae observed in planta was similar to that of the compatible interaction until 24 hpi, and a limited number of hyphae was observed at later time points. At 96 hpi, a few hyphae were ramified or extended into the palissadic mesophyll (Fig. 2H).

Figure 2.

Development of infection structures of compatible (A–G) strain 98AG31 and incompatible strain 93ID6 (H) of M. larici-populina during time-course infection of leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’. A, Aniline blue-stained urediniospores producing several ramified germ tubes at vicinity of stomata and hyphal penetration through stomata without appressorium formation at 2 hpi. B, Urediniospores producing germ tubes and appressoria at vicinity of stomata and primary infection hyphae penetrating through stomata at 6 hpi. C, Substomatal vesicle formed under the abaxial epidermis and infection hyphae developing in the spongy mesophyll at 12 hpi. D, Infection hyphae colonizing the spongy mesophyll at 48 hpi. E, Infection hyphae developing from the spongy mesophyll to the palisade mesophyll at 48 hpi. F, Spongy and palisade mesophyll colonized by infection hyphae at 96 hpi. G, Uredinium formed on the abaxial epidermis releasing newly formed urediniospores at 196 hpi. H, Limited development of hyphae of the incompatible M. larici-populina strain 93ID6 in the mesophyll at 96 hpi compared to compatible strain in F. The hyphae of M. larici-populina were painted in red in F and H to help with visualization of fungal hyphae in plant mesophyll. Fungal infection structures are pinpointed by arrowheads. ap, Appressorium; gt, germ tube; ih, infection hyphae; inf, infection site; nf sp, newly formed spore; pih, primary infection hyphae; sp, spore; ssv, substomatal vesicle; ur, uredinium.

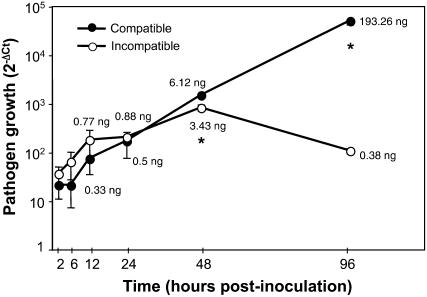

Fungal Growth in Leaves during Compatible and Incompatible Interactions

Assuming that the proportion of fungal and plant biomass present at any given time during an infection is equivalent to the proportion of fungal and plant DNA, quantitation of fungal nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA) internal transcribed spacer (ITS) can be used to estimate the extent of fungal growth in the plant (Boyle et al., 2005). Invasion of foliar tissues by compatible and incompatible strains was monitored in planta by qPCR quantification of M. larici-populina rDNA ITS. In planta growth of compatible and incompatible strains of M. larici-populina was similar during early stages of infection (2, 6, 12, and 24 hpi; Fig. 3). A drastic increase in fungal DNA mass of about 12-fold was observed between 24 and 48 hpi for the compatible strain, while the incompatible strain showed a slower increase (4-fold). The amount of fungal rDNA ITS decreased for the latter strain between 48 and 96 hpi, indicating a possible hyphal decay (Fig. 3). In contrast, growth of the compatible strain dramatically increased at 96 hpi, and DNA mass was more than 500-fold higher than the amount measured for the incompatible strain.

Figure 3.

Time-course infection of leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ by compatible (98AG31) and incompatible (93ID6) strains of M. larici-populina. Development of the two rust strains was followed in planta by specific amplification of the rDNA intergenic ITS region from total DNA extracted from inoculated leaf tissues at 2, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 hpi. Pathogen growth curves correspond to ΔCt of fungal ITS amplicons measured by quantitative PCR. Note the log scale. Estimates of fungal mass DNA are indicated on the graph for the two strains at 12, 24, 48, and 96 hpi. Amplifications were carried out on three biological replicates, and significant differences between the two M. larici-populina strains are indicated by a star (t test; P < 0.05).

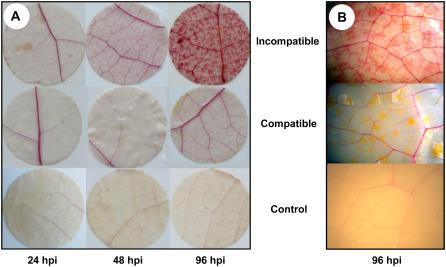

Detection of ROS and Lignin Monomers

Leaf tissues inoculated with compatible and incompatible strains of M. larici-populina showed no endogenous ROS accumulation based on diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining (data not shown). In contrast, control leaves with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) injection and wounded leaves exhibited DAB precipitates (data not shown). Phloroglucinol staining is considered to be specific for cinnamaldehyde end groups present in lignins (Nakano and Meshitsuka, 1992). At 2, 6, 12 (data not shown), 24, and 48 hpi, a light red coloration of vessels of major orders was observable on leaf inoculated with the incompatible strain, and no coloration was visible for the rest of the leaf tissues (Fig. 4A). An intense red coloration of leaf tissues was detected at 96 hpi in leaves inoculated with the incompatible strain (Fig. 4, A and B), whereas staining was restricted to lower orders of leaf vessels in the case of the compatible interaction or in control leaves (Fig. 4A). Infection hyphae of the compatible strain could be observed as yellowish dots in the mesophyll tissue at 96 hpi (Fig. 4B). In control leaf tissues, a light red coloration was restricted to vessels.

Figure 4.

Wiesner coloration revealing monolignol accumulation by a red coloration in leaf discs of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ sampled on detached leaves inoculated with compatible (98AG31) or incompatible (93ID6) strains of M. larici-populina or mock inoculated with water. A, Cleared leaf discs at 24, 48, and 96 hpi in compatible and incompatible interactions and in the control treatment. B, A 10× close-up of leaf discs at 96 hpi. M. larici-populina infecting hyphae are visible by transparency in the case of the compatible interaction.

Defense-Related Genes in a SSH cDNA Library of Rust-Infected Leaves

SSH technology is a powerful approach to identify genes differentially expressed by cells or organisms in specific developmental stages (Diatchenko et al., 1996). A subtractive cDNA library from incompatible rust-infected leaves (12, 24, and 48 hpi), subtracted by RNA from noninoculated leaf tissues, was constructed. Assembly of 1,999 ESTs obtained from the 5′ and 3′ ends of 1,152 SSH cDNAs produced 967 nonredundant tentative consensus (TC) sequences corresponding to 486 different genes. These sequences have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (accession nos. CT027996–CT029994; CT033829). Among them, 357 ESTs (37%) corresponded to singletons, 610 ESTs (63%) were clustered in 129 TC, and approximately 90% of the ESTs were supported on both 5′ and 3′ ends. A BLASTN search showed that 467 of these ESTs have a homolog in the P. trichocarpa genome sequence in the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) database. The remaining TCs showed no significant similarity to any genes in the NCBI databases, suggesting that they are either absent from the current P. trichocarpa genome sequence assembly (version 1.1) or they might be specific to P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’. The sequences showed no significant hits against M. larici-populina and other basidiomycetes genomes on the JGI portal (data not shown).

A summary of homology searches against GenBank using the BLAST algorithm is shown in Supplemental Table S1. ESTs from Rubisco and chlorophyll a/b-binding protein (CAB) genes were not identified in the SSH cDNA library, whereas they represent 24% of a ‘Beaupré’ cDNA leaf library (Kohler et al., 2003), indicating that the SSH library was efficiently depleted from constitutively expressed transcripts. This analysis indicated that the most prevalent ESTs represented genes directly connected with plant defense and nitrogen metabolism. Among these abundant ESTs, an EST matching an inositol-3-P synthase (I3PS) gene was the most frequently detected sequence (199 occurrences; 20% of ESTs; Table I). Several transcripts corresponding to defense-related genes (PR-1, PR-2, PR-3, and PR-5) and pathogen perception (receptor-like kinase [RLK], LRR, and ankyrin protein) were also among the most abundant SSH ESTs. For example, PR-1 transcripts represented about 4% of the SSH transcripts, indicating a striking up-regulation of its expression. A least three distinct types of chitinase-like genes, including basic (PR-8) and acidic (PR-3) chitinases, were expressed in rust-infected leaves. Transcripts coding for Asp aminotransferase, Asn synthetase, and NADH-Glu synthase, with no obvious direct defensive roles, were also abundant in the SSH library.

Table I.

Most prevalent rust-responsive transcripts in leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ inoculated with the incompatible strain 93ID6 of M. larici-populina measured by ESTs redundancy in a SSH-enriched cDNA library

nd, Not detected.

| Contig IDa | Accession No. (5′)b | Accession No. (3′)b | Best Database Match (Species)c | P. trichocarpa Protein ID No.d | Percent (EST No.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2YE21 | CT029167 | CT029166 | I3PS (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) | 832275 | 20.4 (199) |

| 1YH15 | CT029702 | CT029701 | PR-1 (Vitis vinifera) | 550049 | 3.8 (37) |

| 3YM24 | CT028131 | CT028130 | Thaumatin-like protein, PR-5 (Nicotiana tabacum) | 747341 | 2.2 (21) |

| 1YL15 | CT029535 | CT029534 | Protein disulfide isomerase, PDI-3 (Cucumis melo) | 230101 | 1.3 (13) |

| 1YC18 | CT029896 | CT029895 | Asp aminotransferase (Arabidopsis) | 710171 | 1.1 (11) |

| 1YH09 | CT029711 | CT029710 | Chitinase (class I), PR-3 (Medicago sativa) | 831333 | 0.9 (9) |

| 2YE11 | CT029187 | CT029186 | Cyt P450 (Oryza sativa) | 680604 | 0.9 (9) |

| 3YD08 | CT028543 | CT028542 | Asp synthetase (Triphysaria versicolor) | 722643 | 0.9 (9) |

| 3YG19 | CT028393 | CT028392 | Hypothetical protein (Glycine max) | 579371 | 0.8 (8) |

| 2YK09 | CT028933 | CT028932 | Subtilisin-like Ser protease, AIR3 (Arabidopsis) | 810987 | 0.8 (8) |

| 1YI17 | CT029657 | CT029656 | Chitinase, PR-3 (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus) | 586583 | 0.6 (6) |

| 1YK13 | nd | CT029580 | Acidic class III chitinase SE2, PR-3 (Beta vulgaris) | 746640 | 0.6 (6) |

| 2YB13 | CT029291 | CT029290 | RNA helicase (O. sativa) | 755273 | 0.5 (5) |

| 2YB09 | nd | CT029298 | Asp synthetase (Helianthus annuus) | 722643 | 0.5 (5) |

| 1YK07 | CT029592 | CT029591 | Wall-associated kinase (Arabidopsis) | 758034 | 0.5 (5) |

| 1YJ14 | CT029624 | CT029623 | Senescence-related protein (Pyrus pyrifolia) | 265740 | 0.4 (4) |

| 2YI14 | CT029011 | CT029010 | β-1,3-Glucanase, PR-2 (Fragaria × ananassa) | 290846 | 0.4 (4) |

| 1YP01 | CT029388 | CT029387 | Receptor-like protein kinase, RLK (e-value < E-5) | 756597 | 0.4 (4) |

| 3YF23 | CT028431 | CT028430 | LRR protein kinase (Arabidopsis) | 826060 | 0.4 (4) |

| 2YC08 | CT029266 | CT029265 | Disease resistance protein (Arabidopsis) | 788310 | 0.4 (4) |

| 1YG06 | CT029755 | CT029754 | Protein disulfide isomerase, PDI-2 (C. melo) | 565873 | 0.4 (4) |

| 3YD21 | CT028524 | CT028523 | Ankyrin repeat protein (e-value < E-5) | 571736 | 0.4 (4) |

| 2YM21 | CT028822 | CT028821 | β-1,3-Glucanase, PR-2 (Hevea brasiliensis) | 769807 | 0.4 (4) |

| 1YN04 | CT029471 | CT029470 | NADH Glu synthase (Phaseolus vulgaris) | 824538 | 0.4 (4) |

| 1YG23 | CT029729 | CT029728 | Subtilisin-like proteinase (O. sativa) | 790236 | 0.4 (4) |

Representative EST ID from assembly contig.

GenBank accession number of 5′ and 3′ sequences of transcripts.

Best database match (and corresponding species) obtained with a BLASTX query at NCBI.

Protein ID number of the best database match in P. trichocarpa ‘Nisqually-1’ (version 1.1) obtained from a BLASTN search on the JGI Web site (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Poptr1_1/Poptr1_1.home.html).

Identification of Rust-Responsive Genes at 48 hpi Using Whole-Genome Oligoarrays

Microscopy observations (Fig. 2) and qPCR measurement of fungal DNA (Fig. 3) showed a shift in fungal progression between compatible and incompatible interactions at 48 hpi. A strong difference in lignin deposition at infection sites was observed in the case of the incompatible interaction at 96 hpi (Fig. 4), suggesting that the host molecular response probably initiated after the fungus entered into the mesophyll (12 hpi; Fig. 2, D and E) and when haustorial infection structures were differentiating. We thus investigated changes in gene expression in ‘Beaupré’ leaves at 48 hpi in compatible and incompatible interactions (Fig. 1) using the NimbleGen Populus whole-genome expression oligoarray (Tuskan et al., 2006). We identified 280 (0.4%) and 1,730 (2.6%) transcripts differentially accumulated (≥2-fold) in the compatible and incompatible interactions, respectively, compared to control leaves mock inoculated with water (Table II; Supplemental Table S2). Among these transcripts, 150 showed an increased concentration ≥3-fold in the incompatible interaction and only seven in the compatible interaction.

Table II.

Expression ratios of rust-responsive transcripts from P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ measured with the NimbleGen P. trichocarpa whole-genome expression oligoarray at 48 hpi in ‘Beaupré’ leaves inoculated with incompatible (I48) or compatible (C48) strains of M. larici-populina

| NimbleGen Probe IDa | P. trichocarpa Protein ID No.b | I48-Fold- Regulationc | P Valuec | Best BLAST Hitd | AGI No.e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TREE0002S00038855 | 678883 | 30.6 | 8.77E-12 | No hit (RISP) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00039697 | 272826 | 14.8 | 2.65E-10 | GST U2 (Nicotiana benthamiana) | At1g17170 |

| TREE0002S00058098 | 792358 | 9.6 | 5.49E-07 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At1g58170 |

| TREE0002S00060385 | 277644 | 7.6 | 1.57E-06 | GST parC, auxin-regulated protein (N. tabacum) | At1g78380 |

| TREE0002S00000329 | 711753 | 7.5 | 4.92E-06 | PR protein (dirigent-like protein; Pisum sativum) | At1g64160 |

| TREE0002S00058872 | 657351 | 7.2 | 1.67E-07 | GST 18 (P. alba × P. tremula) | At2g29420 |

| TREE0002S00001434 | 731797 | 7.1 | 8.96E-06 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein, SAG21 (Arabidopsis) | At4g02380 |

| TREE0002S00000421 | 712863 | 6.5 | 1.96E-05 | UDP-Glc:protein transglucosylase-like protein (Lycopersicon esculentum) | At3g02230 |

| TREE0002S00040010 | 276538 | 6.4 | 1.47E-05 | GST parC, auxin-regulated protein (N. tabacum) | At1g17180 |

| TREE0002S00035838 | 795681 | 6.3 | 7.03E-06 | Acidic chitinase (P. tetragonolobus) | At5g24090 |

| TREE0002S00032433 | 581980 | 6.2 | 1.07E-05 | PR-1 protein (Arabidopsis) | At2g14610 |

| TREE0002S00028427 | 746640 | 6.2 | 1.13E-05 | Acidic endochitinase, glycoside hydrolase family 18 (Medicago truncatula) | At5g24090 |

| TREE0002S00052008 | 820835 | 6.2 | 4.67E-06 | GST 18 (P. alba × P. tremula) | At2g29420 |

| TREE0002S00028575 | 748543 | 6.1 | 1.33E-05 | PR-1 protein (Arabidopsis) | At2g14610 |

| TREE0002S00000256 | 710544 | 6.0 | 7.90E-05 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein, SAG21 (Arabidopsis) | At4g02380 |

| TREE0002S00015535 | 769807 | 5.5 | 1.10E-05 | β-1,3-Glucanase (H. brasiliensis) | At4g16260 |

| TREE0002S00028427 | 746640 | 5.4 | 1.13E-05 | Acidic endochitinase, glycoside hydrolase family 18 (M. truncatula) | At5g24090 |

| TREE0002S00024163 | 417599 | 5.3 | 1.20E-05 | RLK5 (Arabidopsis) | At5g25930 |

| TREE0002S00063111 | 248394 | 5.3 | 3.19E-05 | PSII CP43 protein (Panax ginseng) | AtCg00280 |

| TREE0002S00000638 | 714634 | 5.3 | 1.57E-05 | Hypothetical protein (P. deltoides × Populus maximowiczii) | At4g19950 |

| TREE0002S00040235 | 279076 | −4.1 | 1.75E-03 | rRNA intron-encoded homing endonuclease (O. sativa) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00063251 | 256788 | −4.2 | 1.18E-02 | Lys decarboxylase (O. sativa) | At5g06300 |

| TREE0002S00047596 | 735328 | −4.2 | 5.07E-04 | Ribosomal protein 40S S9 (Solanum demissum) | At5g39850 |

| TREE0002S00047882 | 640496 | −4.2 | 1.16E-04 | β-Tubulin (Gossypium hirsutum) | At5g12250 |

| TREE0002S00063570 | Cp_orf79 | −4.2 | 1.17E-03 | Hypothetical chloroplastic protein (Spinacia oleracea) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00062228 | 418172 | −4.5 | 7.99E-04 | Magali Spm transposable element 60I2G03 (P. deltoides) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00040045 | 277030 | −4.6 | 5.33E-04 | Hypothetical chloroplastic protein (Saccharum officinarum) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00063598 | cp_orf61 | −4.6 | 4.47E-03 | Hypothetical protein SpolCp101 (S. oleracea) | AtCg00300 |

| TREE0002S00035479 | 795166 | −4.8 | 1.99E-03 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00030128 | 596748 | −4.8 | 5.91E-04 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase (O. sativa) | At1g28640 |

| TREE0002S00032920 | 585246 | −5 | 1.32E-03 | Hypothetical chloroplast ATPase (Ycf2; P. alba) | AtCg00860 |

| TREE0002S00039944 | 275797 | −5.6 | 2.95E-02 | Hypothetical chloroplastic protein (Cuscuta reflexa) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00056518 | 771095 | −5.8 | 7.19E-03 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00040050 | 277108 | −5.9 | 3.51E-03 | Hypothetical chloroplastic protein (N. tabacum) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00031244 | 587419 | −6 | 1.17E-02 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00063597 | cp_ycf15 | −6.6 | 1.97E-03 | Hypothetical protein (Orf77/Ycf15-A; Arabidopsis) | AtCg00870 |

| TREE0002S00023106 | 195834 | −7 | 3.12E-03 | Hypothetical auxin-induced protein (Capsicum annuum) | At4g34800 |

| TREE0002S00042443 | 820269 | −7.2 | 3.04E-02 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At4g25030 |

| TREE0002S00060995 | 290970 | −8 | 2.98E-03 | Lys decarboxylase-like protein (O. sativa) | At5g06300 |

| TREE0002S00040072 | 277323 | −8.1 | 3.46E-03 | Hypothetical chloroplastic protein (N. tabacum) | No hit |

| NimbleGen Probe IDa | P. trichocarpa Protein ID No.b | C48-Fold- Regulationc | P Valuec | Best BLAST Hitd | AGI No.e |

| TREE0002S00055699 | 594680 | 4.2 | 2.22E-03 | Anthocyanin acyltransferase-like protein (Arabidopsis) | At5g39050 |

| TREE0002S00029168 | 837131 | 3.6 | 9.66E-04 | Ferredoxin-nitrite reductase (Betula pendula) | At2g15620 |

| TREE0002S00037742 | 811643 | 3.3 | 3.16E-03 | CuZn-superoxide dismutase (P. tremula × P. tremuloides) | At2g28190 |

| TREE0002S00009339 | 568530 | 3.2 | 1.87E-02 | LRR-containing hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At5g55540 |

| TREE0002S00067017 | 544845 | 3 | 4.55E-02 | Integrase polyprotein (M. truncatula) | At2g15650 |

| TREE0002S00001434 | 731797 | 3 | 9.18E-03 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein, SAG21 (Arabidopsis) | At4g02380 |

| TREE0002S00048762 | 679519 | 3 | 3.74E-03 | Polyubiquitin UBQ10 (Arabidopsis) | At4g05320 |

| TREE0002S00052689 | 566171 | 2.9 | 7.56E-03 | β-Ketoacyl-CoA synthase (O. sativa) | At5g43760 |

| TREE0002S00034768 | 794254 | 2.8 | 2.72E-03 | Aldo/keto reductase (M. truncatula) | At3g53880 |

| TREE0002S00041247 | 291991 | 2.7 | 1.37E-02 | Rubisco, large chain (Lophocolea martiana) | AtCg00490 |

| TREE0002S00063977 | 588636 | 2.7 | 4.92E-03 | gag/pol polyprotein (S. demissum) | At2g14380 |

| TREE0002S00060457 | 279164 | 2.7 | 7.55E-03 | RLK (Arabidopsis) | At4g27300 |

| TREE0002S00063843 | 660789 | 2.7 | 1.07E-02 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00028989 | 826800 | 2.6 | 8.29E-03 | Ser/Thr protein kinase (M. truncatula) | At5g09890 |

| TREE0002S00030792 | 583368 | 2.6 | 1.43E-02 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00048783 | 748355 | 2.6 | 1.02E-02 | Pollen coat protein-like (Arabidopsis) | At5g38760 |

| TREE0002S00007567 | 561703 | 2.6 | 5.65E-03 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00061579 | 172038 | 2.6 | 2.93E-03 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At1g08440 |

| TREE0002S00002619 | 818390 | 2.5 | 1.66E-02 | Calcium-binding protein (Atriplex nummularia) | At3g50360 |

| TREE0002S00024949 | 421059 | 2.5 | 3.45E-03 | Δ-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (G. max) | At2g39800 |

| TREE0002S00059712 | 263964 | −4.3 | 1.58E-02 | Lys decarboxylase-like protein (O. sativa) | At5g06300 |

| TREE0002S00020096 | 648814 | −4.6 | 3.00E-02 | Hypothetical splicing factor (Arabidopsis) | At2g16940 |

| TREE0002S00023106 | 195834 | −4.6 | 2.82E-02 | Hypothetical auxin-induced protein (C. annuum) | At4g34800 |

| TREE0002S00037394 | 793544 | −4.8 | 1.58E-03 | Hypothetical protein (O. sativa) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00060995 | 290970 | −5.1 | 1.67E-02 | Lys decarboxylase-like protein (O. sativa) | At5g06300 |

| TREE0002S00047970 | 817423 | −5.3 | 2.73E-03 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At5g42050 |

| TREE0002S00055491 | 591262 | −5.4 | 1.21E-02 | Cys proteinase (Alnus glutinosa) | At2g27420 |

| TREE0002S00056518 | 771095 | −5.4 | 1.14E-02 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00031048 | 585596 | −5.5 | 3.10E-03 | Calcium-binding protein (Arabidopsis) | At4g13440 |

| TREE0002S00047850 | 827481 | −5.8 | 2.75E-02 | Zinc finger protein PHD family (G. max) | At2g02470 |

| TREE0002S00054306 | 588374 | −6.3 | 4.23E-04 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00058200 | 789011 | −6.4 | 4.83E-03 | Pollen coat oleosin-Gly rich protein (Arabidopsis) | At5g07565 |

| TREE0002S00066249 | 660216 | −6.6 | 6.71E-03 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00031244 | 587419 | −6.7 | 8.78E-03 | No hit | No hit |

| TREE0002S00064258 | 681711 | −6.9 | 2.92E-03 | Magali Spm transposable element 60I2G03 (P. deltoides) | No hit |

| TREE0002S00029354 | 589352 | −7.1 | 3.54E-02 | Hypothetical protein, sec34 homolog (Arabidopsis) | At1g73430 |

| TREE0002S00050427 | 274646 | −7.4 | 3.04E-03 | Phosphoprotein phosphatase (Arabidopsis) | At1g05000 |

| TREE0002S00061299 | 298144 | −8.7 | 3.82E-03 | Lys decarboxylase-like protein (O. sativa) | At5g06300 |

| TREE0002S00044995 | 583302 | −10.5 | 6.67E-03 | Calcium-binding EF-hand family protein-like (Arabidopsis) | At2g44310 |

| TREE0002S00047844 | 732714 | −11 | 1.50E-02 | Hypothetical protein (O. sativa) | At5g24610 |

Probe ID number on NimbleGen Populus expression array version 2.0 (NCBI GEO platform GPL2699).

Protein ID number of corresponding best gene model in the P. trichocarpa ‘Nisqually-1’ genome sequence (version 1.1) at http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Poptr1_1/Poptr1_1.home.html.

Expression ratios (and associated P value) calculated between normalized transcript concentration of inoculated versus mock-inoculated (water) Populus leaves obtained with duplicated probes on NimbleGen whole-genome oligoarray and three biological replicates, ratios <1.0 were inverted and multiplied by −1 to aid their interpretation.

Best database match (and corresponding species) obtained with a BLASTX query at NCBI.

AGI number of best Arabidopsis homolog.

Incompatible Interaction

The transcript showing the highest rust-induced accumulation (32-fold) in the incompatible interaction corresponded to a P. trichocarpa gene model (protein identification [ID] no. 678883) with no sequence similarity in the nonredundant NCBI database or the Arabidopsis genome. The corresponding genomic sequence is located at the beginning of scaffold 5,059 of the P. trichocarpa genome assembly and is truncated in 5′. This transcript showed a strong homology with several Populus ESTs in NCBI dbEST. These ESTs are longer in their 5′ and 3′ ends of nucleotide sequences and encode an 82-amino acid polypeptide with no ortholog in databases. SignalP 3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) analysis identified a signal peptide of 24-amino acid length, and Phobius (http://phobius.cgb.ki.se/) predicted a noncytoplasmic localization for the protein, suggesting a putative localization outside of the plant cell.

Genes encoding enzymes known to be associated with the host defense response were highly induced at 48 hpi in the incompatible interaction and presented no significant regulation in the compatible interaction. These genes encode several types of PR proteins, such as PR-1 homologs, basic glucan-endo-1,3-β-glucosidase (PR-2), thaumatin-like, and osmotin-like proteins (PR-5), which were also identified in the SSH cDNA library and PR-10-like proteins. All those PR transcripts showed an increase ≥3-fold compared to the mock-inoculated treatment.

Among other transcripts showing an important induction in the incompatible interaction (≥5-fold accumulation), we detected transcripts coding for components of the signaling pathways (calmodulins), an RLK, and the I3PS identified in the SSH library. Transcripts related to secondary metabolism and cell wall synthesis, such as dirigent-like proteins, chalcone-, flavonol-, and tropinone reductases, were also detected among transcripts significantly accumulated in the incompatible interaction supporting the observed accumulation of phloroglucinol-stained lignin monomers (Fig. 4A).

Several rust-induced genes corresponded to different members of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene family. Twelve different GST transcripts showed at least a 2-fold accumulation in the incompatible interaction compared to the mock-inoculated treatment. The most strongly accumulated GST transcripts consisted of two phylogenetic groups of sequences (group 1, protein ID nos. 276538, 277644, and 272826; and group 2, protein ID nos. 657351 and 820835; Table II) that shared a high sequence similarity (≥90%). Alignment of the oligonucleotide probe sequences matching these GST sequences revealed a significant overlap that may have resulted in possible cross hybridizations between transcript species. Nevertheless, all transcripts that were strongly accumulated belonged to the tau GST class and not to other classes (i.e. phi, theta, and zeta GSTs) described so far in plants (Dixon et al., 2002; Wagner et al., 2002).

There were a few transcripts (292) showing a decrease in concentration at 48 hpi in the incompatible interaction. These include several chloroplastic transcripts, as well as different transcripts coding transposable elements, including the magali Spm-like transposable elements (protein ID no. 418172) located within a rust-resistance locus in P. deltoides (Lescot et al., 2004). A transcript encoding a Lys decarboxylase also showed a dramatic decrease in concentration at 48 hpi (8-fold). Most of these transcripts also presented a decrease in concentration in the compatible interaction (Table II).

Compatible Interaction

Only a few transcripts were significantly up- or down-regulated in the compatible interaction (158 and 122, respectively). The highest increase (4.2-fold) corresponded to a transcript coding for an anthocyanin acyltransferase-like protein. Several transcripts corresponding to signaling components (Ser/Thr kinase, calcium-binding protein) and LRR-containing proteins, including an RLK, were significantly induced (≥2.5-fold). Interestingly, a transcript coding a Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylase (protein ID no. 421059) showed a 2.5-fold induction. This protein is involved in Pro biosynthesis, and a regulation of transcripts involved in the catabolism of Pro was previously described specifically in the flax (Linum usitatissimum)-Melampsora lini compatible interaction (Ayliffe et al., 2002).

Identification of Rust-Responsive Genes at 48 hpi Using cDNA Microarrays

Before the availability of the NimbleGen whole-genome expression oligoarrays, we carried out a series of transcript profilings of rust-infected (incompatible interaction) and mock-inoculated (control) P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ leaves at 48 hpi using 28 K Platform for Integrated Clone Management (PICME) cDNA microarrays. Thus, these datasets obtained on different plants (year 2004) than those for oligoarray-based expression profiling (year 2005) were compared to the oligoarray expression profiles.

We identified 1,614 transcripts corresponding to 1,055 P. trichocarpa gene models that were significantly accumulated or decreased (≥2-fold) at 48 hpi in the incompatible interaction compared to control leaves. Among these transcripts, 218 showed an increased concentration ≥3-fold and 136 a decreased concentration ≤3-fold. Transcripts accumulated in response to the rust infection are mostly identical to those described in the oligoarray expression profiling (Table III; Supplemental Table S3). The highest levels of rust induction (≥8-fold) were observed for transcripts coding PR proteins, such as PR-1, PR-2, PR-5, PR-8, and PR-10, and the rust-induced secreted protein (RISP) number 678883. GST transcript corresponding to protein ID number 820835 showed a 5.9-fold induction. In addition, two transcripts coding GSTs not significantly regulated in the whole-genome oligoarray analysis and belonging to the same rust-induced tau GST class (see above) were detected as significantly induced on PICME microarrays (protein ID no. 670248, 9.4-fold; protein ID no. 658124, 6-fold).

Table III.

Expression ratios of rust-responsive transcripts in leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ measured with the PICME 28 K cDNA Populus microarray at 48 hpi in ‘Beaupré’ leaves inoculated with the incompatible (I48) strain of M. larici-populina versus mock-inoculated leaves

The highest expression ratio is presented for gene models (P. trichocarpa protein ID no.) represented by different cDNA probes on the array.

| PICME ID No.a | P. trichocarpa Protein ID No.b | Best BLAST Hit (Species)c | I48-Fold- Regulationd | Bayes-lnP Valued | AGI No.e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJ773363 | 669475 | Thaumatin-like protein, PR-5 (Actinidia deliciosa) | 28.8 | 5.40E-07 | At4g11650 |

| AJ773115 | 751998 | β-1,3-Glucanase, PR-2 (Fragaria × ananassa) | 28.7 | 3.00E-06 | At4g16260 |

| AJ777100 | 595857 | Basic PR protein, PR1 (ATPRB1; Arabidopsis) | 25.7 | 1.02E-05 | At2g14580 |

| AJ769638 | 711753 | PR protein, dirigent-like protein (P. sativum) | 23.8 | 9.26E-05 | At1g64160 |

| CA822510 | 678883 | No hit (RISP) | 19.4 | 1.41E-03 | No hit |

| AJ777741 | 769807 | β-1,3-Glucanase, PR-2 (H. brasiliensis) | 15.1 | 5.45E-06 | At4g16260 |

| AJ774585 | 746640 | Acidic endochitinase, PR-3 (M. truncatula) | 14.4 | 2.33E-06 | At5g24090 |

| AJ770319 | 645750 | LRR, putative disease resistance protein (Arabidopsis) | 13.1 | 1.14E-04 | At1g74170 |

| CF235659 | 732511 | Heavy metal transport/detoxification protein (M. truncatula) | 13.1 | 1.72E-04 | At3g07600 |

| AJ774712 | 792358 | Dirigent protein (Arabidopsis) | 12.7 | 1.71E-04 | At1g58170 |

| CB239336 | 654817 | Ascorbate oxidase (L. esculentum) | 11.6 | 2.05E-05 | At4g39830 |

| CB239610 | 754908 | Calmodulin-binding protein, NPGR1 (Arabidopsis) | 11.1 | 1.68E-06 | At1g27460 |

| AJ779296 | 758549 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | 10.9 | 4.82E-03 | At1g61667 |

| AJ780675 | 171587 | Putative receptor protein kinase, PERK1 (G. max) | 10.6 | 1.22E-04 | At1g52290 |

| CA825881 | 286375 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | 10.5 | 7.55E-03 | At3g17380 |

| CA824683 | 654672 | No hit | 10.5 | 3.02E-04 | No hit |

| CF229868 | 567801 | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | 10.4 | 1.4E-02 | At5g10695 |

| AJ780826 | 748543 | PR protein, PR-1 (Arabidopsis) | 10.3 | 4.59E-06 | At2g14610 |

| AJ777924 | 722998 | Heavy metal transport/detoxification protein (M. truncatula) | 9.7 | 2.40E-04 | At3g07600 |

| AJ771768 | 641396 | E-class Cyt P450, group I (M. truncatula) | 9.6 | 2.86E-05 | At1g12740 |

| AJ769643 | 837541 | ras-related GTP-binding protein (N. tabacum) | −4.2 | 3.01E-03 | At5g45130 |

| AJ780783 | 197959 | Ribosomal protein 30S S5 (Arabidopsis) | −4.2 | 1.11E-02 | At2g33800 |

| AJ775019 | 282386 | Ser/Thr protein kinase (Arabidopsis) | −4.2 | 9.31E-05 | At3g53030 |

| CA821048 | 565812 | Hypothetical protein PGR5 (Arabidopsis) | −4.3 | 1.40E-04 | At2g05620 |

| AJ780576 | 824324 | Triacylglycerol/steryl ester lipase-like protein (M. truncatula) | −4.3 | 9.86E-05 | At5g14180 |

| CA821054 | 431886 | Rubisco activase (G. hirsutum) | −4.4 | 1.20E-04 | At2g39730 |

| AJ772360 | 568201 | Thi4 thiamine biosynthetic enzyme (Citrus sinensis) | −4.5 | 5.36E-04 | At5g54770 |

| AJ773302 | 814251 | CAB (Daucus carota) | −4.5 | 7.30E-05 | At5g54270 |

| AJ774495 | 800945 | Nine-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase4 (P. sativum) | −4.6 | 8.37E-04 | At4g19170 |

| AJ768470 | 249554 | Dienelactone hydrolase (M. truncatula) | −4.6 | 1.39E-04 | At1g35420 |

| CA820871 | 657524 | Galactinol synthase, isoform GolS-1 (Ajuga reptans) | −4.7 | 2.80E-04 | At1g60470 |

| AJ773153 | 589333 | Peroxiredoxin Q (P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides) | −4.7 | 1.61E-05 | At3g26060 |

| AJ774710 | 671325 | PSI light-harvesting antenna CAB (B. vulgaris) | −4.7 | 8.23E-05 | At3g47470 |

| AJ773223 | 817727 | Thi1 thiamine biosynthetic enzyme (Picrorhiza kurrooa) | −4.8 | 2.89E-05 | At5g54770 |

| CA821119 | 744667 | Light-harvesting complex II type III CAB (Vigna radiata) | −5.1 | 4.44E-05 | At5g54270 |

| AJ770887 | 724963 | PSI light-harvesting CAB (N. tabacum) | −5.3 | 2.33E-05 | At3g54890 |

| CF232422 | 597692 | SMAD/FHA (M. truncatula) | −5.6 | 1.34E-03 | At3g13780 |

| AJ774616 | 551646 | Pepsin A (Arabidopsis) | −7.8 | 5.22E-05 | At1g09750 |

| AJ772852 | 261110 | Pro-rich protein (G. max) | −9.5 | 1.79E-05 | At2g45180 |

| CF229292 | 825296 | Lipid-binding protein (Arabidopsis) | −12.5 | 2.8E-02 | At3g53980 |

Probe ID number on the PICME 28K cDNA Populus microarray (http://www.picme.at/).

Protein ID number of corresponding best gene model in the P. trichocarpa ‘Nisqually-1’ genome sequence (version 1.1) at http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Poptr1_1/Poptr1_1.home.html.

Best database match (and corresponding species) obtained with a BLASTX query at NCBI.

Expression ratios calculated between inoculated versus mock-inoculated (water) normalized transcript concentration values and associated P value obtained from two independent biological replicates, ratios <1.0 were inverted and multiplied by −1 to aid their interpretation.

AGI number of best Arabidopsis homolog.

Several Cyt-P450 transcripts showed contrasting expression profiles, some being strongly induced and others repressed as observed on the whole-genome oligoarray. Several other transcripts related to redox regulation also showed a slight decrease in concentration at 48 hpi in the incompatible interaction (e.g. peroxidases, thioredoxin), whereas other transcripts in the same cellular category were strongly induced (e.g. GSTs, protein disulfide isomerase, and peroxidases). Several transcripts involved in the photosynthetic machinery and carbon metabolism (e.g. light-harvesting complex CAB, PSI and PSII polypeptides, Rubisco, RuBisCO activase) and two different transcripts involved in thiamin biosynthesis showed a decreased concentration at 48 hpi in the incompatible interaction.

Validation of Rust-Regulated Genes Using cDNA Macroarrays and RT-qPCR

Expression data were further carried out at 12, 24, and 48 hpi in both compatible and incompatible interactions by either a RT-qPCR approach or reverse-northern on a Populus 4 K cDNA Nylon macroarray (Supplemental Table S4) with different sets of biological replicates than those used in the expression profiling experiments described above.

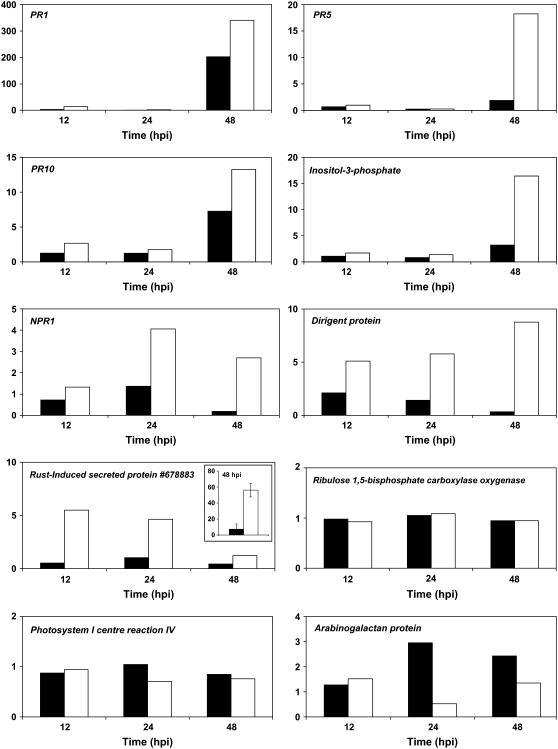

We measured transcripts coding for PR-1, PR-5, and PR-10 proteins as typical genes triggered by host defense reactions at 48 hpi in leaf tissues. The transcripts coding for I3PS (protein ID no. 832275), the dirigent-like protein (protein ID no.711753), NPR1 (protein ID no. 253241), and the RISP (protein ID no. 678883) that showed the highest transcripts accumulation based on the whole-genome oligoarrays, cDNA microarrays, or SSH library sequencing were also measured. Genes coding for a PSI center reaction subunit (protein ID no. 711610) and the small subunit of the Rubisco (protein ID no. 813777) that were slightly down-regulated during both types of interactions were included in the set of genes tested by RT-qPCR.

Strong accumulation of the selected rust-induced transcripts was confirmed by RT-qPCR amplification in leaf tissues challenged by the incompatible strain of M. larici-populina compared to mock-inoculated tissues. Maximum induction of PR genes was reached at 48 hpi (Fig. 5), and, interestingly, NPR1 transcript showed a peak of expression at 24 hpi. The transcript coding the RISP (protein ID no. 678883) with the highest accumulation (32-fold) detected at 48 hpi with whole-genome oligoarray profiling showed a different profile with RT-qPCR. A strong induction (7-fold) was measured at earlier time points in the incompatible interaction, and a lower induction level was detected at 48 hpi. We thus measured the level of this latter transcript by RT-qPCR with the RNA samples used to perform the whole-genome oligoarray hybridizations, and we observed a 56 (±8)-fold accumulation at 48 hpi (Fig. 5). This observation confirmed that the rate of induction is influenced by the physiological status of the infected plants rather than strong technical biases in array measurement. In some cases, RT-qPCR revealed a late induction of transcripts coding PR proteins (e.g. PR-1 and PR-10; Fig. 5) at 48 hpi in the compatible interaction with lower levels than those reached in the incompatible interaction, whereas array analysis did not reveal such induction.

Figure 5.

RT-qPCR expression patterns for transcripts of proteins PR-1, PR-5, PR-10, I3PS, NPR1, dirigent-like protein, RISP number 678883, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase, arabinogalactan protein, and PSI center reaction IV. Total RNA of mock-inoculated or inoculated leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ with either compatible (black bars) or incompatible (white bars) strains of M. larici-populina 12, 24, and 48 hpi was isolated, and aliquots of 1 μg were used for first-strand cDNA synthesis. PCR was performed with 2 μL of first-strand cDNA. A control with no RT in the first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction mix was included to control for the lack of genomic DNA. The Populus ubiquitin transcript (GenBank ID CA825222) was used as a control for transcript not regulated by rust. Inset, Data for the RISP number 678883; transcript concentration was measured by RT-qPCR on the RNA samples used for the whole-genome oligoarray analysis at 48 hpi (n = 3).

Comparison of the Different Transcript Profiling Approaches

Genes showing striking differences in transcript concentration during the incompatible interaction were detected by the different transcript profiling approaches, i.e. SSH cDNA sequencing, whole-genome oligoarrays, cDNA microarrays, cDNA macroarrays, and RT-qPCR, indicating consistency of the various approaches (Fig. 5; Table IV), although the regulation ratio may vary. For example, the RISP transcript that showed the highest accumulation (32-fold) based on the whole-genome oligoarrays was represented by several ESTs on the cDNA microarrays and showed a level of accumulation over 10-fold (protein ID no. 678883; Table III). In contrast, the strongly induced transcript coding PR-5 protein (protein ID no. 669475) showed a 28.8-fold induction based on the cDNA microarray and was quite abundant in the SSH library (2% of the cDNA clones), whereas a lower level was detected on the whole-genome oligoarray. The I3PS transcript that was highly abundant in the SSH library (approximately 20.4% of the cDNA clones) only showed approximately 5-fold accumulation in both whole-genome oligoarray and cDNA microarray analyses. In addition to bias resulting from the different technologies (full-length cDNA versus 60-mer oligonucleotide probes), differences in mRNA accumulation detected between the various profiling approaches likely reflect the fact that RNA were extracted from different sets of biological replicates with delayed plant defense response due to the variable physiological status of cuttings grown in greenhouse. A high proportion of rust-induced genes were identified in the SSH library. This technique presents the potential of identifying rare transcripts or genes expressed locally that may be missed in microarray expression profiling (e.g. statistics stringency in array analysis). Thus, this approach is not redundant but complementary to array-based transcriptome profiling.

Table IV.

List of significantly rust-induced transcripts detected using different transcriptome-based expression analyses in leaves of P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ inoculated by the incompatible M. larici-populina strain 93ID6 compared to mock-inoculated (water) control leaves at 48 hpi

Expression ratios (fold-induction) measured with NimbleGen whole-genome oligoarrays, PICME cDNA microarrays, or Nylon-based cDNA macroarrays are given. Transcripts were selected when identified through at least two different approaches and based on their expression ratios (at least 3-fold induction in one of the transcriptomic assay). Matches of a transcript sequence with an EST from a rust-responsive Populus leaves cDNA library (SSH) are indicated (×). –, Data are not available (not detected, not significant, or not present on array or in cDNA library).

| Populus Protein ID No.a | NimbleGen Populus Oligoarray | PICME cDNA Microarray | cDNA Macroarray | SSH EST | Best BLAST Hit (Species)b | AGI Homologc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 678883 | 30.6 | 19.4 | 4.3 | – | RISP (P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides) | No hit |

| 669475 | 3.9 | 28.8 | 23.3 | × | Thaumatin, PR-5 protein (A. deliciosa) | At4g11650 |

| 832275 | 5 | 4.2 | 26.9 | × | I3PS (Nicotiana paniculata) | At5g10170 |

| 769807 | 5.5 | 15.1 | 19.2 | × | Glucan endo-1,3-β-d-glucosidase, PR-2 (H. brasiliensis) | At4g16260 |

| 180318 | 3.5 | 9.4 | 10.9 | – | Osmotin-like protein (G. hirsutum) | At4g11650 |

| 761866 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 7.4 | – | Hypothetical protein (G. max) | At4g16380 |

| 731797 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 2.8 | – | Senescence-associated gene 21, SAG21 (Arabidopsis) | At4g02380 |

| 820835 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 3.9 | – | GST18 (P. alba × P. tremula) | At1g10370 |

| 826324 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 6.0 | – | Kunitz trypsin inhibitor 3, Pop-TI3 (P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides) | At1g73325 |

| 727757 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 5.3 | – | 1,4-Benzoquinone reductase (P. armeniaca) | At4g27270 |

| 726588 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 5.6 | – | Hexose transporter (V. vinifera) | At5g26340 |

| 706088 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 | – | Tropinone reductase (Arabidopsis) | At1g07440 |

| 800516 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 3.8 | – | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At4g27450 |

| 175325 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 2.9 | – | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase-like protein (Arabidopsis) | At4g34200 |

| 266069 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.1 | – | S-Adenosyl-methionine decarboxylase uORF (O. sativa) | At5g15950 |

| 595857 | 4.5 | 25.7 | – | – | PR-1 protein (V. vinifera) | At2g14580 |

| 711753 | 7.5 | 23.8 | – | × | Disease resistance protein dirigent-like protein (P. sativum) | At1g64160 |

| 746640 | 6.2 | 14.4 | – | × | Acidic chitinase (class III), PR-3 (M. truncatula) | At5g24090 |

| 732511 | 2.1 | 13.1 | – | – | Heavy metal transport/detoxification protein (M. truncatula) | At3g07600 |

| 792358 | 9.6 | 12.7 | – | – | Hypothetical protein (dirigent-like protein; Arabidopsis) | At1g58170 |

| 567801 | 3.5 | 10.4 | – | × | No hit | No hit |

| 748543 | 6.1 | 10.3 | – | – | PR-1 protein (Arabidopsis) | At2g14610 |

| 641396 | 3.2 | 9.6 | – | – | Cyt P450, E-class P450, group I (M. truncatula) | At1g12740 |

| 714634 | 5.3 | 9.2 | – | – | Hypothetical protein (P. deltoides × P. maximowiczii) | At4g19950 |

| 722643 | 3.1 | 9.0 | – | × | Gln-dependent Asn synthetase type II (P. vulgaris) | At3g47340 |

| 290737 | 3.1 | 8.3 | – | – | Protein disulfide isomerase-like protein, PDI-3 (C. melo) | At1g60420 |

| 712863 | 6.5 | 4.0 | – | × | UDP-Glc transglucosylase-like protein, SlUPTG1 (L. esculentum) | At3g02230 |

| 554725 | 2.2 | 6.3 | – | – | RLK LRR protein (S. tuberosum) | At1g34210 |

| 755695 | 2.9 | 6.2 | – | – | NIMIN1 (Arabidopsis) | At1g02450 |

| 710544 | 6.0 | 4.8 | – | – | Senescence-associated gene 21, SAG21 (Arabidopsis) | At4g02380 |

| 823332 | 3.6 | 5.7 | – | – | ATP-binding cassette transporter (PtrATH2; Arabidopsis) | At3g47730 |

| 259624 | 3.0 | 5.5 | – | – | Dicyanin (blue copper-binding protein; L. esculentum) | At5g20230 |

| 829298 | 2.7 | 5.1 | – | – | Peroxidase (P. trichocarpa) | At3g49120 |

| 593975 | 2.3 | 5.2 | – | – | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycotransferase, DGL1 (Arabidopsis) | At5g66680 |

| 673066 | 4.1 | 3.1 | – | – | Reversibly glycosylated polypeptide (T. aestivum) | At5g15650 |

| 422974 | 4.1 | 2.5 | – | – | ATP-binding cassette transporter, abc2 homolog (Arabidopsis) | At3g47780 |

| 575987 | 3.9 | 3.6 | – | – | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At3g22160 |

| 828962 | 3.2 | 3.9 | – | × | GST (Caragana korshinskii) | At1g17180 |

| 659435 | 3.9 | 2.1 | – | – | Wound-induced protein WI12 (Arabidopsis) | At3g10985 |

| 202273 | 3.8 | 3.4 | – | – | LRR receptor-like Ser/Thr protein kinase, RLK5 (Arabidopsis) | At1g09970 |

| 646543 | 3.6 | 3.7 | – | – | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (H. brasiliensis) | At4g11820 |

| 711719 | 3.7 | 2.9 | – | – | Heat shock protein 70 (Cucumis sativus) | At5g42020 |

| 826060 | 3.1 | 3.6 | – | × | Putative disease resistance protein (LRR; Arabidopsis) | At2g25470 |

| 822404 | 2.5 | 3.5 | – | – | 60S Acidic ribosomal protein PO (Euphorbia esula) | At2g40010 |

| 827148 | 2.4 | 3.5 | – | – | Hypothetical protein, putative prenylated rab receptor (O. sativa) | At3g13710 |

| 758330 | 2.8 | 3.5 | – | – | Dirigent-like protein pDIR9 (Picea engelmannii × Picea glauca) | At1g55210 |

| 418525 | 3.5 | 2.5 | – | – | Pro-rich lipid-binding protein (G. max) | At2g10940 |

| 586871 | 3.4 | 2.2 | – | – | No hit | No hit |

| 818818 | 2.7 | 3.3 | – | × | Heat shock protein 90, SHD (Arabidopsis) | At4g24190 |

| 830497 | 3.2 | 3.1 | – | × | Putative membrane protein (S. tuberosum) | At1g36580 |

| 580121 | 2.2 | 3.1 | – | × | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At4g21700 |

| 726993 | 3.1 | 3.1 | – | – | Quinone reductase (Arabidopsis) | At4g27270 |

| 793953 | 2.7 | 3.1 | – | – | Cyt P450 (Persea americana) | At4g13290 |

| 823674 | 2.5 | 3.1 | – | – | Hevein-like (P. tremula × P. alba) | At3g04720 |

| 837012 | 3.0 | 2.2 | – | – | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Arabidopsis) | At3g02360 |

| 822983 | 2.1 | – | 9.5 | – | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Arachis hypogaea) | At1g78870 |

| 712259 | 2.3 | – | 6.9 | – | Developmental protein DG1118 (Arabidopsis) | At1g73030 |

| 556400 | 2.5 | – | 6.1 | – | 40S Ribosomal protein S19 (Arabidopsis) | At5g61170 |

| 829835 | 2.1 | – | 5.1 | – | trans-Caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase, CCoAMT-2 (P. trichocarpa) | At4g34050 |

| 729723 | 2.2 | – | 4.8 | – | CuZn-superoxide dismutase (P. alba × P. tremula) | At1g08830 |

| 580782 | 2.2 | – | 4.8 | × | 14-3-3 protein (Populus × canescens) | At3g02520 |

| 558203 | 2.4 | – | 4.1 | – | Translation elongation factor (Arabidopsis) | At5g19510 |

| 721294 | 2.5 | – | 4.0 | – | Cytochrome c1 (Arabidopsis) | At5g40810 |

| 831066 | 2.7 | – | 4.0 | – | Monosaccharide transporter (P. tremula × P. tremuloides) | At1g11260 |

| 256724 | 2.6 | – | 3.9 | – | Cytosolic l-ascorbate peroxidase (Codonopsis lanceolata) | At3g09640 |

| 830146 | 2.0 | – | 3.9 | × | Ribosomal protein 60S L3 (S. tuberosum) | At1g43170 |

| 552351 | 2.6 | – | 3.8 | – | Acidic ribosomal protein 60S P1 (Zea mays) | At1g01100 |

| 675956 | 2.4 | – | 3.6 | – | Cytosolic l-ascorbate peroxidase (G. max) | At3g09640 |

| 575698 | 2.6 | – | 3.5 | – | Enolase (O. sativa) | At2g36530 |

| 770546 | 2.6 | – | 3.5 | – | Ribophorin (Arabidopsis) | At2g01720 |

| 834126 | 3.3 | – | 2.1 | – | Pentameric polyubiquitin (Nicotiana sylvestris) | At4g02890 |

| 553829 | 3.3 | – | 2.9 | – | Pectin methylesterase (P. tremula × P. tremuloides) | At3g14310 |

| 724015 | 3.1 | – | 3.1 | – | S-Adenosyl-methionine synthetase (P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides) | At1g02500 |

| 654817 | – | 11.6 | 3.2 | – | Ascorbate oxidase (L. esculentum) | At4g39830 |

| 727577 | – | 9.4 | 3.1 | – | PR protein (P. deltoides × P. maximowiczii) | At1g24020 |

| 667694 | – | 7.9 | 3.2 | – | Sinapyl alcohol dehydrogenase-like protein (P. tremula × P. tremuloides) | At4g37970 |

| 827390 | – | 7.3 | 7.5 | – | PR protein (P. deltoides × P. maximowiczii) | At1g24020 |

| 728031 | – | 5.5 | 4.9 | – | Nitrate-induced NOI protein (Arabidopsis) | At5g55850 |

| 421939 | – | 3.6 | 3.2 | – | Zinc finger DNA-binding protein (C2H2 domain; Catharanthus roseus) | At1g27730 |

| 588763 | – | 2.5 | 4.1 | – | Ethylene response factor, AP2 family, EREBP (Arabidopsis) | At5g47230 |

| 669494 | 4.1 | – | – | × | Lipoprotein A, expansin, blight-associated protein p12 (O. sativa) | At4g30380 |

| 565873 | 3.91 | – | – | × | Protein disulfide isomerase, PDI-3 (Quercus suber) | At1g60420 |

| 569255 | 3.84 | – | – | × | Fe(II)/ascorbate oxidase (Arabidopsis) | At4g10500 |

| 795101 | 3.55 | – | – | × | Protein disulfide isomerase-like protein, PDI-3 (C. melo) | At1g60420 |

| 586583 | 3.42 | – | – | × | Acidic chitinase, PR-3 (M. truncatula) | At5g24090 |

| 670783 | 3.16 | – | – | × | No hit | No hit |

| 751998 | – | 28.7 | – | × | β-1,3-Glucanase, PR-2 (Fragaria × ananassa) | At4g16260 |

| 831333 | – | 8.5 | – | × | Chitinase, basic, PR-8 (Elaeagnus umbellata) | At3g12500 |

| 680604 | – | 7.6 | – | × | Cyt P450 E-class, group I (M. truncatula) | At1g12740 |

| 760140 | – | 7.3 | – | × | Syringolide-induced protein B13-1-1 (G. max) | At4g39830 |

| 824336 | – | 6.6 | – | × | Formate dehydrogenase (Quercus robur) | At5g14780 |

| 802053 | – | 6.1 | – | × | β-Galactosidase (Fragaria × ananassa) | At3g13750 |

| 832905 | – | 5.1 | – | × | Cyt P450 (Cicer arietinum) | At4g37370 |

| 579371 | – | 3.7 | – | × | Hypothetical protein (zinc finger; G. max) | At4g16380 |

| 829431 | – | 3.7 | – | × | Heat shock protein 70 (C. sativus) | At5g42020 |

| 816882 | – | 3.7 | – | × | α-Mannosidase (Arabidopsis) | At3g26720 |

| 826206 | – | 3.6 | – | × | Taxadiene 5-α hydroxylase, Cyt P450 (O. sativa) | At5g36110 |

| 729244 | – | 3.1 | – | × | Peroxidase precursor (Q. suber) | At5g05340 |

| 836795 | – | – | 4 | × | F0F1-ATPase γ-subunit (Ipomoea batatas) | At2g33040 |

| 822499 | – | – | 3.1 | × | ras-related protein RAB8-1 (N. tabacum) | At3g46060 |

| 676990 | – | – | 3.1 | × | Hypothetical protein (Arabidopsis) | At3g29780 |

Protein ID number of corresponding best gene model in the P. trichocarpa ‘Nisqually-1’ genome sequence (version 1.1) at http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Poptr1_1/Poptr1_1.home.html.

Best database match and corresponding species obtained with a BLASTX query at NCBI.

AGI number of best Arabidopsis homolog.

DISCUSSION

Reactions that lead to programmed cell death in incompatible interactions between plant and hemi-biotrophic or necrotrophic pathogens preventing the pathogen to spread in plant tissues have been largely described in several plant pathosystems (Heath, 2000). In contrast, interactions involving biotrophic pathogens, with their sophisticated type of pathogenesis that keeps plant cells alive and minimizes tissue damage in susceptible hosts, are poorly known. The uredinial stage of rust fungi is generally taking place through stomatal penetration, and most studies suggest that host compatibility requires the ability for the fungus to avoid or negate prehaustorial defenses within the substomatal cavity of the host leaf, breach the mesophyll plant cell wall to form the first haustorium, and develop a biotrophic interaction with the living invaded cell to support further fungal growth (Schulze-Lefert and Panstruga, 2003; Glazebrook, 2005; Spanu, 2006). Recent work described haustorially expressed secreted proteins of the rust biotrophic pathogen M. lini (Catanzariti et al., 2006) that led to HR when expressed in planta, indicating a probable direct R-Avr recognition system in flax challenged by an avirulent strain of M. lini (Dodds et al., 2006).

In this study, we describe at the microscopic, histological, and transcriptomic levels a novel pathosystem involving P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ challenged by urediniospores of the leaf rust basidiomycete M. larici-populina. ‘Beaupré’ is resistant to M. larici-populina isolate 93ID6 (pathotype 3-4) and susceptible to isolate 98AG31 (pathotype 3-4-7; Barrès et al., 2006). Unexpectedly, there was no significant difference in fungal growth from spore germination to contact with mesophyll cell between these two isolates. Spore germlings of both isolates were able to penetrate the leaf through stomatas in the first hours after inoculation, forming primary infection structures (i.e. substomatal vesicles) in the spongy mesophyll and reaching mesophyll cells for infection. Appressoria were formed on the leaf surface but are not a prerequisite to penetrate inside plant tissues, as frequent direct hyphal penetration through stomatas were observed. Based on the amount of fungal rDNA, differences of growth in planta were only noticeable between compatible and incompatible isolates after 24 hpi (Fig. 3). The compatible isolate then spread in leaf tissues and colonized the whole mesophyll, while the incompatible strain remained in the spongy mesophyll (Fig. 2, F and H). Fungal growth increased until the compatible strain developed spore-forming cells and produced typical golden pustules filled with masses of urediniospores on the lower leaf surfaces between 6 and 7 dpi. At this stage, the resistant phenotype was generally characterized by the presence of scattered necrotic lesions and the absence of macroscopic symptoms. Similar responses have been reported in P. deltoides × Populus nigra ‘Ogy’ inoculated with virulent and avirulent isolates of M. larici-populina (Laurans and Pilate, 1999).

We were not able to detect H2O2 accumulation through DAB staining in leaf tissues challenged by the incompatible strain of M. larici-populina. H2O2 production possibly occurred transiently and only in plant cells challenged by M. larici-populina during infection. Supporting this assumption, several genes encoding enzymes of the redox regulation pathways such as GSTs, ascorbate peroxidases, and superoxide dismutase were highly up-regulated at 48 hpi. Studies conducted at the protein level confirmed the up-regulation of thioredoxin and peroxiredoxin during Populus-Melampsora interaction (Rouhier et al., 2004; Vieira Dos Santos et al., 2005). The lack of H2O2 accumulation has been previously reported in plants interacting with biotroph pathogens (Glazebrook, 2005). This may reflect the specific and complex biotrophic relationships between rust and living host cells. As observed by Laurans and Pilate (1999) and in this study, the necrotic tissues are highly localized to a limited area (Fig. 1), supporting the fact that H2O2 production related to HR was not spreading far from infection sites in leaf tissues.

Phloroglucinol staining confirmed that a massive production of monolignols was induced upon inoculation of plant tissues by the incompatible rust strain (Fig. 4). Such compounds are believed to play a role in plant defense (Dixon, 2001). Several genes of the phenylpropanoid pathways and dirigent-like proteins encoding genes were induced at 48 hpi in inoculated leaves prior to observation of the maximum level of phloroglucinol staining. Strong production of secondary metabolites in colonized leaves likely led to the synthesis of phytoalexins and lignin deposition in secondary cell walls restricting the fungal proliferation, as shown in the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata)-Uromyces vignae interaction and in other pathosystems involving biotrophic fungal pathogens (Heath, 1997, 2000). Callose synthase and Phe ammonia-lyase genes are often reported as marker genes of lignin and callose deposition, although the levels of induction may strongly vary from one interaction to another. In this study, the homologs of Populus Phe ammonia-lyase and callose synthase were not significantly induced during the incompatible interaction at the time points tested. Induction of dirigent proteins encoding transcripts has been reported in conifers submitted to wounding or insect attacks (Ralph et al., 2006b), and their products may participate in a general stress response in trees submitted to biotic or abiotic stress.

Studying the transcriptome of rust-infected leaves with whole-genome oligoarray harboring more than 45,000 putative gene models from the P. trichocarpa genome sequence (Tuskan et al., 2006) identified 2,397 rust-responsive genes (approximately 3% of the total set of arrayed genes) that may play a role in defense reactions in the incompatible interaction or, conversely, in supporting fungal growth in susceptible plants. As expected from previous studies in model species (Schenk et al., 2000; Mahalingam et al., 2003), many functional groups of genes were found to be involved in the defense response, including signal transduction pathways components, genes stimulated during biotic or abiotic stress responses, and genes of primary and secondary metabolisms. A striking alteration in steady-state RNA populations took place at 48 hpi, whereas few genes were regulated at earlier stages of interaction when tested by RT-qPCR or cDNA macroarrays. This suggests that gene expression in response to rust infection is activated later after the fungal cells entered into contact with the leaf surface and colonized the substomatal cavity. Recognition of the pathogen is likely taking place upon triggering of specific recognition mechanisms when fungal hyphae are elongating within the mesophyll and attempt to penetrate the plant cell wall barrier to form haustorial structures (Fig. 2). Presence of strongly inducible genes in the incompatible interaction indicates that the rust infection has had a significant impact on the leaf transcriptome despite the limited amount of fungal mycelium (Fig. 3) during the early stages of invasion. The observed differences between the transcriptomes of leaves infected by either the compatible or incompatible isolates were striking. The incompatible strain elicited up-regulation of a wide range of defense-related genes (e.g. PR proteins, GSTs), whereas these genes were not induced by the compatible strain.

Several genes that may participate in the perception of the rust pathogen by sensing avirulence products released by invading hyphae were differentially accumulated in the incompatible interaction between P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides and M. larici-populina. We identified transcripts coding for putative LRR disease resistance proteins (protein ID nos. 645750 and 826060) that showed an induction of their expression (Table IV). Transcripts coding for LRR receptor protein kinases (protein ID nos. 417599 and 171587), showing homology with RLK5 and PERK1, respectively, were also induced during the incompatible interaction. PERK1 encodes a putative receptor kinase with an extracellular domain with sequence identity to cell wall-associated extensin-like proteins. PERK1 transcripts are rapidly expressed upon mechanical wounding in response to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and SA and methyl jasmonate application (Silva and Goring, 2002). RLK5, also named HAESA, is involved in the control of floral abscission in Arabidopsis (Haffani et al., 2004). These receptor kinases belong to a large family that had been shown to play a role in microbial sensing, and they may likely participate in pathogen perception in poplar. In flax, the M. lini products of the avirulence gene Avr567 are expressed in haustoria and recognized inside plant cells (Dodds et al., 2004). This recognition occurs through a direct interaction with the L resistance genes products of flax (Dodds et al., 2006). L genes are members of the NBS-LRR resistance gene family (Ellis et al., 1999). We did not identify any members of this family among rust-induced genes. These plant proteins are responsible for the detection of pathogens in natural conditions and should be constitutively expressed; thus, their expression may not necessarily be under transcriptional control during the infection process. None of the rust-induced putative receptors and LRR proteins is located in the superclusters of NBS-LRR R genes containing the MER locus (Tuskan et al., 2006) or close to the rust-resistance loci identified in poplar by genetic mapping (Cervera et al., 2004; Lescot et al., 2004; Jorge et al., 2005). Strikingly, a significant induction of RLK transcripts was also detected in the compatible interaction at 48 hpi (2.7-fold).

Upon recognition of the pathogen aggression, a complex network of signaling enzymes and molecules relays the information in the plant cell to the nucleus, where specific defense-related gene expression is triggered. As shown in several other plant-fungus interactions, components of the signaling pathways were induced in the incompatible interaction between P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ and M. larici-populina. These include transcripts from the calcium- and ethylene-related pathways, calmodulin, calreticulin, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase, 14-3-3 proteins, and ethylene-responsive element-binding protein (EREBP) and MYB family transcription factors. NPR1 is an important regulator of PR gene expression through binding to transcriptional regulators TGA elements and a low accumulation (approximately 2-fold) of its transcript has been reported in different pathosystems (Glazebrook, 2005). P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ NPR1 transcript (protein ID no. 253241) was accumulated at 24 and 48 hpi in poplar leaves during the incompatible interaction (Fig. 5) prior the strong induction observed for targeted PR genes. Interestingly, we also detected the induction of a transcript coding for NPR1/NIM1-interacting protein (NIMIN-1) at 48 hpi (Table IV). NIMIN-1 directly interacts with NPR1 and can modulate its activity and expression of PR genes in Arabidopsis (Weigel et al., 2005). A gene that showed among the highest levels of induction, using the different transcript profiling approaches, encoded an I3PS. The protein is involved in the production of inositol-P, a metabolite that could lead to the production of various products such as phosphatidylinositides, cell wall components, or oligosaccharides of the raffinose series (Loewus and Murthy, 2000). Phosphatidylinositols, like inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, are important secondary messengers of the cell transduction pathways that play a crucial role in calcium homeostasis in plant cells (Munnik et al., 1998). Involvement of calcium-related signaling in plant-rust interaction has been previously reported (Xu and Heath, 1998). Several calcium-binding proteins encoding genes are induced in poplar leaves during the incompatible interaction with M. larici-populina, and I3PS may contribute to the production of phosphatidylinositols involved in calcium regulation. Considering the strong induction of I3PS transcript in poplar leaves during the incompatible interaction with M. larici-populina, addressing the exact role of inositol-P in response to either biotic or abiotic stress requires further investigation.

Within transcripts with the highest rust-induced accumulation (>10-fold) in the incompatible interaction, several encoded PR proteins, such as PR-1, PR-2 (1,3-β-glucanase), PR-3 (acidic chitinase), PR-5 (thaumatin-like protein), PR-8 (basic chitinase), and PR-10 (ribonuclease). All these enzymes are known for their antifungal properties (Van Loon and Van Strien, 1999) and are typical SA-induced marker genes of plant response to bacterial and fungal attacks (Van Loon and Van Strien, 1999; Schenk et al., 2000). There is evidence that Uromyces rust species are susceptible to apoplastic PR proteins, including PR-1 (Rauscher et al., 1999). Interestingly, a gene encoding a PR-10 protein was also activated in epidermal cells of resistant cowpea challenged by the cowpea rust fungus and prior of the fungus entering the cell lumen (Mould et al., 2003). We identified many expressed hypothetical proteins among rust-responsive genes. Of interest is the RISP whose transcript showed the strongest (32-fold) induction in the incompatible interaction in the whole-genome oligoarray analysis. The RISP may play a role in early defense against M. larici-populina, and it remains to address its exact role to determine whether it is a novel PR protein in Populus.

In a compatible biotrophic interaction, the invading hyphae are able to alter the host-plant metabolism in such a way that increasing amounts of nitrogen and carbon metabolites are mobilized and translocated to fungal cells (Mendgen and Hahn, 2002; Panstruga, 2003; Both et al., 2005). In the compatible interaction between P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘Beaupré’ and M. larici-populina, we did not detect a striking induction of metabolism-related elements, and only a few genes encoding transporters and enzymes of the carbon metabolism were slightly induced with the cDNA-macroarray experiment. We observed a 2.5-fold induction of a Populus transcript encoding a Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (protein ID no. 421059; Table II) in the compatible interaction, whereas no induction of this gene was observed in the incompatible interaction. This enzyme catalyzes the two first steps of Pro synthesis. The fis1 transcript encodes a Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase, which is specifically expressed in the flax-M. lini compatible interaction (Ayliffe et al., 2002). FIS1 is involved in the catabolism of Pro to Glu, and a possible link between such catabolic activity and the fungal metabolism remains unclear.