Abstract

Children with epilepsy, even those with new-onset seizures, exhibit relatively high rates of behavior problems. The purpose of this study was to explore the relationships among early temperament, family adaptive resources, and behavior problems in children with new-onset seizures. Our major goal was to test whether family adaptive resources moderated the relationship between early temperament dimensions and current behavior problems in 287 children with new-onset seizures. Two of the three temperament dimensions (difficultness and resistance to control) were positively correlated with total, internalizing, and externalizing behavior problems (all p < 0.0001). The third temperament dimension, unadaptability, was positively correlated with total and internalizing problems (p < 0.01). Family adaptive resources moderated the relationships between temperament and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems at school. Children with a difficult early temperament who live in a family environment with low family mastery are at the greatest risk for behavior problems.

Keywords: epilepsy, seizures, child, family environment, temperament, behavior problems

INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders in children and adolescents, affecting 3–5% at some time in their lives [1]. Children with epilepsy have been shown to be at increased risk for psychopathology [2, 3] as well as for problems with adjustment, including behavior, and cognition [4–9]. Children with seizures are up to 4.7 times more likely to have behavior problems than control children [4, 8, 10, 11]. Children with epilepsy also have more behavior problems than children with other chronic conditions that do not involve the central nervous system [7, 8]. This increased risk for behavior problems has been shown to be present prior to the recognition of seizures [10]. Behavioral problems can adversely affect children’s developmental outcomes, making it important for factors associated with such problems to be described. Identifying these factors will provide a foundation for the development of clinical interventions.

The child’s early temperament might be a risk factor for behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Temperament is described as biologically based characteristic patterns of emotional reactivity and self-regulation [12]. Temperament characteristics are early-appearing, core personality traits that are relatively stable, although they can show some change with development [13]. Environmental influences affect how the biological bases of temperament are expressed [14]. Andersson et al. [15] propose that biological and social risk factors interact with specific temperament dimensions to increase the likelihood of the emergence of behavior problems. In general population children, temperamental factors are associated with behavior problems [13, 16], with fussy-difficult and persistent temperaments being the strongest predictors of behavior problems [15]. Other researchers found that infants with a difficult temperament were three times more likely to be in the clinical range of behavior problems than those without a difficult temperament [17].

Although no studies of temperament in children with epilepsy have yet been published, children who have a chronic illness not involving the brain have been found to display less adaptive temperaments than healthy children. For example, Egyptian children with a chronic disease (i.e., leukemia, congenital heart disease, or asthma) were found to have more persistent, less adaptable, and more difficult temperaments than healthy children [18]. In addition, children with cardiac disease showed negative temperaments in terms of being more withdrawn and more intense than healthy children [19]. Finally, temperaments in children with asthma were characterized by lower regularity, lower adaptability, lower intensity of reaction, more negative mood, and lower persistence compared to those in either healthy children or in children with a chronic skin or allergy disorder but not asthma [20].

Although the literature on temperament in children with chronic neurological disorders is limited, it appears that these children also show difficult temperamental profiles. For example, children with attention problems and hyperactivity were found to have lower adaptability and persistence and higher activity and negative mood compared to controls [21]. The children with attention problems and hyperactivity were over-represented in the three most difficult temperament groups. In addition, studies of adults with disorders involving the brain have also suggested more problematic temperaments [22, 23]; however, this research has generally not been extended to younger populations. It is unclear if children with chronic illnesses actually have more difficult temperaments than children from the general population. Chronically ill children have more behavior problems compared to both children without a chronic condition and normal child populations [24–27]. It is not known how these behavior ratings correspond to parental ratings of temperament. Regardless, parents’ perception of their child influences parental behavior and has implications for adjustment and coping in relation to a chronic illness.

Studies of children with epilepsy have primarily investigated the association of other types of variables (e.g., seizure variables) with behavior problems [5, 10, 28, 29], and no studies have investigated temperament as a predictive variable in this population. In a model of family adjustment to epilepsy [30], however, Austin proposed that dimensions of temperament are an important set of child characteristics that might influence the development of a problematic adaptation outcome in children with epilepsy [30]. In addition, she proposed that other characteristics, such as family environment (e.g., stressors, adaptive resources) also influence child outcomes. Specifically, family adaptive resources are proposed to serve as a protective factor and help reduce the development of child behavior problems. There is support in the literature for the assertion that more adaptive resources in the family environment (e.g., family mastery and family esteem/communication) are associated with fewer behavior problems in children with epilepsy [6, 31–33]. It has been found that low family mastery [6, 33] and low parent confidence in managing their child’s discipline [6] are strongly associated with more child behavior problems. These two family characteristics were also the strongest predictors of child behavior problems over a 2-year period in children with new-onset seizures [6]. The study by McCusker et al. [31] revealed that a less cohesive and more conflictual family environment was associated with negative behavioral outcomes and poorer social competency in children with epilepsy.

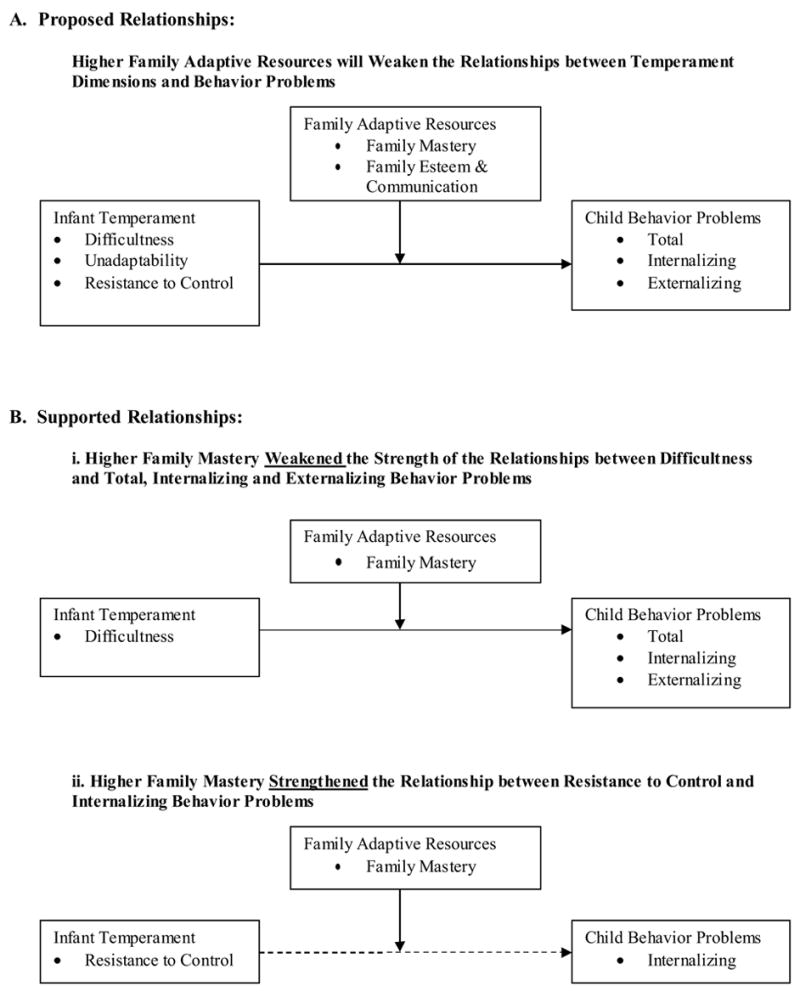

No studies have investigated the family environment as a moderator of the relationship between temperament and behavior problems in children with seizures. The present study addresses this gap. In a further elaboration of a portion of Austin’s model, we hypothesized that family adaptive resources would moderate the relationships between early dimensions of temperament and behavior problems (see Figure 1-A). We proposed that children with a negative early temperament would have fewer behavior problems if they were reared in families with more adaptive resources compared to families with fewer adaptive resources.

Figure 1.

As part of a larger study of adaptation to new-onset seizures we explored relationships among the child’s temperament in infancy, family adaptive resources, and current child behavior problems. First, we explored the association between early temperament and current behavior problems. We hypothesized that more negative temperaments would be associated with more child behavior problems. Second, we developed a model in which we hypothesized that family adaptive resources would moderate the association between dimensions of temperament and behavior problems. Specifically, we proposed that the relationship between a negative early temperament and behavior problems would be weaker in a family with more adaptive resources.

METHOD

Participants

Subjects were 287 children who had recently had a first-recognized seizure and were ages 6 to 14 years old (M = 9.6, SD = 2.6). The 350 children in the larger study were recruited from children’s hospital neurology clinics in Cincinnati and Indianapolis (68.9%), from community private neurologists (10.5%), and through referrals from school nurses (20.6%). Children who had had their first recognized seizure within the past three months were recruited. Additional child inclusion criteria were: no prior antiepileptic medication; no complex febrile seizures; the seizure could not be associated with recent head injury, malignant brain tumor, toxic or metabolic condition, meningitis, or encephalitis; and the child could not have any other chronic health problem requiring long-term care. Children who were judged to be mentally handicapped (based on available IQ scores or placement in full-time special education programs) were excluded from the analyses. Parents of the subjects had a mean of 13.9 years of education. Additional demographic and seizure data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Child Demographic and Seizure Data (N=287)

| N | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 137 | 47.7% |

| Female | 150 | 52.3% |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 245 | 85.4% |

| African-American | 28 | 9.8% |

| Hispanic | 2 | 0.7% |

| Asian | 2 | 0.7% |

| Native American | 1 | 0.3% |

| Bi-Racial | 7 | 2.4% |

| Other | 2 | 0.7% |

| Seizure Type | ||

| General Tonic Clonic | 75 | 26.1% |

| Absence | 39 | 13.6% |

| Elementary Partial | 19 | 6.6% |

| Complex Partial | 64 | 22.3% |

| Atonic, akinetic, myoclonic | 4 | 1.4% |

| Partial with Secondary Generalization | 80 | 27.9% |

| Undetermined | 6 | 2.1% |

| Seizure Syndrome | ||

| Idiopathic | 136 | 47.4% |

| Cryptogenic | 107 | 37.3% |

| Symptomatic | 19 | 6.6% |

| Undetermined if cryptogenic or symptomatic | 4 | 1.4% |

| Undetermined if focal or generalized | 18 | 6.3% |

| Undetermined | 3 | 1.0 % |

Informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of each participant, and assent was obtained from each child. Permission to contact the child’s teacher was also obtained from each child’s parent/guardian. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

Instrumentation

Past studies relied upon parents to rate their child’s behavior problems [3–5, 10, 29, 33]. However, previous research has revealed limited convergence in raters’ reports of behavior problems [11, 34–36], making obtaining data from more than one informant a priority. In this study parents rated the child’s early temperament and family adaptive resources and teachers were asked to rate the child’s behavior in the school setting. We used different informants for the measurements of temperament and behavior to reduce the possibility of the shared variance between temperament and behavior problems being due to the informant.

Temperament

Within three months of their child’s first recognized seizure, parents (94% of whom were mothers) participated in structured phone interviews during which they completed the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire – Retrospective Form (RICQ) to rate retrospectively the child’s early temperament [37]. The RICQ is a shorter, retrospective version of the ICQ [38], which is a widely used parent-perception instrument. The RICQ is a brief measure that consists of 16 items related to early temperament. These items are rated using 7-point Likert scales, with higher scores reflecting more negative temperaments. Three subscale scores are obtained: difficultness (negative emotionality), unadaptability (novelty distress), and resistance to control (unmanageability). Cronbach’s alphas were calculated for each of these subscales in our sample, and were all excellent, ranging from 0.83 to 0.87. In terms of validity, the RICQ has shown adequate estimates of temperamental characteristics during infancy [37]. In the study by Bates et al. [37], mothers completed the ICQ when their children were between 6 and 24 months of age; then, ten years later, the same mothers retrospectively assessed their children’s infant temperament via the ICQ – Retrospective Form (RICQ). They found that the two reports, separated by 10 years, were significantly correlated in all three domains.

Behavior Problems

The child’s teacher was asked to complete the Child Behavior Checklist Teacher’s Report Form (TRF) [39] based on the child’s behavior during the two months prior to his or her first recognized seizure. Each item is rated on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat/sometimes true), and 2 (very/often true). Scores are computed for Total Behavior Problems, Internalizing Problems, and Externalizing Problems. Internalizing problems consist of problems relating to withdrawal, somatic complaints, and anxiety/depression. Externalizing behaviors refer to behaviors such as aggression and delinquency [40]. The TRF has been shown to have high reliability and stability and provides standardized scores for age and gender [39]. It has also been used extensively in children with epilepsy [28, 34].

Family Adaptive Resources

The major caregiving parent was asked to complete items from two subscales (family mastery and family esteem/communication) on the Family Inventory of Resources for Management (FIRM) [41] based on the six-month period prior to the child’s first recognized seizure. Items were rated on 4-point scales: 0 (not at all), 1 (minimally), 2 (moderately), and 3 (very well), with a higher score reflective of a more adaptive family environment. The family mastery subscale consists of items that assess family emotion, sense of control over events, level of cooperation among family members, and family organization. Family affection and effective communication among family members were measured by the family esteem and communication subscale. Cronbach’s alphas were calculated for both of these subscales in our sample. The alphas were excellent: 0.91 for family mastery and 0.86 for family esteem and communication.

Data Analyses

To explore the relationship between temperament and behavior problems, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the bivariate association between each of the three ICQ subscales (difficultness, unadaptability, and resistance to control) and each of the three TRF subscales (Total Behavior Problems, Internalizing Problems, and Externalizing Problems).1 Raw scores were used for the TRF in the analyses. Using standardized T-scores can reduce the range of scores because children with different raw scores can have the same T-score; raw scores preserve this sample variability. Our sample of children with new-onset seizures had a high number of low standardized scores.

To test the hypothesis that family adaptive resources moderated the relationship between early temperament and behavior problems, three multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate the interaction between early temperament and family adaptive resource variables on each of the TRF behavior subscales. Each regression analysis included the two family adaptive resource variables (family mastery and family esteem/communication), the three early temperament variables (difficultness, unadaptability, and resistance to control), and the six interaction terms between each of the respective family and temperament scores. The interaction terms were used to test the extent to which each of the family variables moderated the relationship between each of the dimensions of temperament and behavior problems. Results are presented after the removal of non-significant interaction terms. Age, race (Caucasian vs. non-Caucasian), sex, and years of education of the primary caregiver (to reflect SES) were included in all models.

Because the three TRF subscales (Total Behavior Problems, Internalizing Problems, and Externalizing Problems) were all positively skewed, bootstrap analyses [42] were carried out to verify that the distributions of the estimates for the correlation coefficients and for the interaction terms in the final models obtained from the analyses above were normally distributed, thus ensuring that correct statistical inferences were being drawn. Ten thousand datasets of the same size as the original dataset were created by randomly sampling with replacement from the original dataset. For each correlation coefficient and for each final model obtained above, the analysis was repeated using each of the 10,000 bootstrap datasets. The estimates obtained from each of the 10,000 analyses were then plotted to approximate the distribution of the estimate. The distributions of all estimates were found to be normally distributed, demonstrating that even though the outcomes were skewed, the sample size was large enough that the estimates still had normal distributions.

RESULTS

As a group, the children did not have overtly problematic infant temperaments. For all three temperament dimensions, mean item scores fell between 3 and 4 on the 7-point scale. In addition, approximately 75% of the scores were less than or equal to 4 on all three dimensions. Nevertheless, between 10 and 18% of the children had mean scores over 5 on the dimensions. Parents also reported relatively high levels of family adaptive resources, with mean scores falling above 2 for 91% of the family mastery scores and above 1.5 for 97% of the family esteem and communication scores. On the other hand, child behavior problems were slightly elevated, as reflected by the mean total behavior problem score (raw score = 28, T-score = 53.8). Complete means and standard deviations for all three measures are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Variables

| N | MEAN | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Temperament | |||

| Difficultness | 287 | 3.41 | 1.15 |

| Unadaptability | 287 | 3.07 | 1.49 |

| Resistance to control | 287 | 3.43 | 1.51 |

| Behavior Problems (raw scores) | |||

| Total behavior problems | 287 | 28.13 | 28.04 |

| Internalizing problems | 287 | 7.22 | 7.62 |

| Externalizing problems | 287 | 5.82 | 9.86 |

| Family Adaptive Resources | |||

| Family mastery | 287 | 2.27 | 0.51 |

| Family esteem and communication | 287 | 2.35 | 0.43 |

The first hypothesis, predicting that dimensions of temperament would be significantly associated with current child behavior problems, was primarily supported. All three measures of early temperament had moderate positive correlations with both total behavior and internalizing problem scores (all p < 0.01). As difficultness, unadaptability, and resistance to control increased, both total behavior problems and internalizing behavior problems increased. In addition, both difficultness and resistance to control had moderate positive correlations with the externalizing problem score (p < 0.05), but unadaptability was not significantly correlated with the externalizing problem score (p = 0.0753). As difficultness and resistance to control increased, the externalizing problem score also increased. Correlations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations between Early Temperament and Child Behavior Problems

| Child Behavior Problems | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Temperament | Total | Internalizing | Externalizing | |||

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | |

| Difficultness | 0.20 | 0.0006 | 0.26 | <0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.0183 |

| Unadaptability | 0.19 | 0.0016 | 0.23 | <0.0001 | 0.11 | 0.0753 |

| Resistance to control | 0.19 | 0.0011 | 0.18 | 0.0022 | 0.13 | 0.0335 |

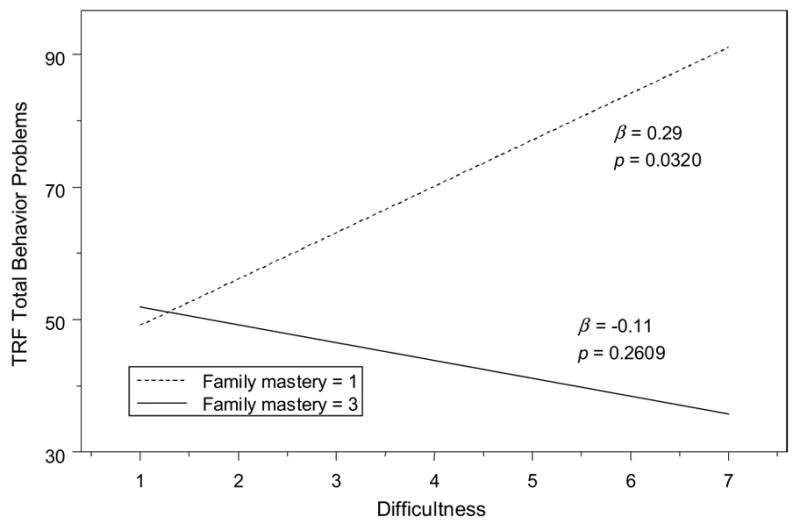

The second hypothesis, predicting that family adaptive resources would moderate the relationship between early temperament and child behavior problems, was partially supported. In the first multiple regression with total behavior problems as the dependent variable, there was a significant interaction between the family adaptive resource of family mastery and the infant temperament dimension of difficultness (F1,273 = 4.59, p = 0.0330). There was a stronger association between difficultness and total behavior problems in families with low mastery than in families with high mastery. For a family mastery score of 1 (indicating low family mastery), the standardized beta for the association between difficultness and total behavior problems was 0.29 (p = 0.0320). For a family mastery score of 3 (indicating high family mastery), the standardized beta for the association between difficultness and total behavior problems was −0.11 (p = 0.2609). In families with low mastery, children with more difficult early temperaments tended to have higher total behavior problem scores, whereas in families with high mastery there was not a significant association between difficultness and total behavior problems. This relationship is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of family mastery on the association between early difficultness and total problems

Internalizing Problems

In the second multiple regression, which had internalizing problems as the dependent variable, there were significant interactions between the family adaptive resource of family mastery and the temperament dimension of difficultness (F1,272 = 8.89, p = 0.0031), and between family mastery and the temperament dimension of resistance to control (F1,272 = 6.30, p = 0.0127). The relationships among difficultness, family mastery, and internalizing problems were similar to those seen with total behavior problems. In families with low mastery there was a significant positive association between difficultness and internalizing behavior problems, but in families with high mastery this association was not significant. For a family mastery score of 1 (indicating low family mastery), the standardized beta for the association between difficultness and internalizing behavior problems was 0.53 (p = 0.0006). For a family mastery score of 3 (indicating high family mastery), the standardized beta for the association between difficultness and internalizing behavior problems was −0.13 (p = 0.2418). The moderating effect of family mastery is reflected in the weakening of the association between difficultness and internalizing behavior problems in families with high mastery compared to families with low mastery.

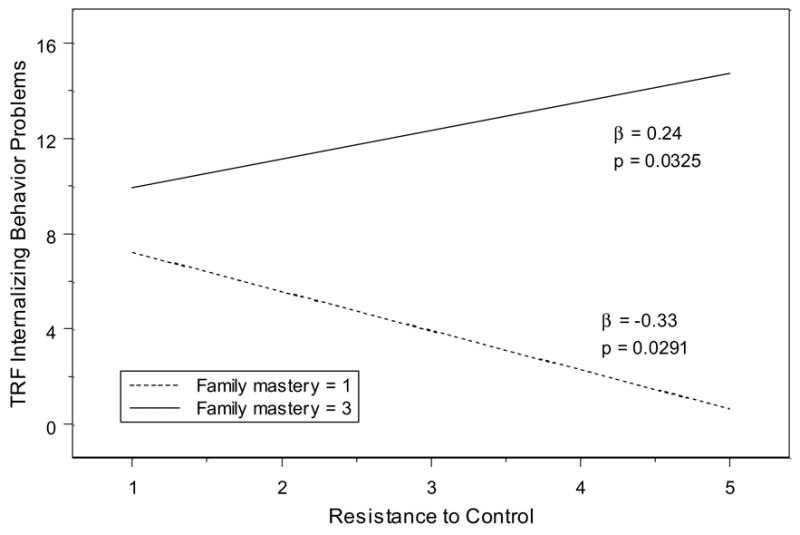

In contrast to the other temperament dimensions, in families with low mastery there tended to be a negative association between resistance to control and internalizing problems, whereas the association was slightly positive in families with high mastery. For a family mastery score of 1, the standardized beta for the association between resistance to control and internalizing problems was −0.33 (p = 0.0291); for a family mastery of 3, the standardized beta for this association was 0.24 (p = 0.0325). The moderating effect of family mastery is reflected in resistance to control being more negatively associated with internalizing problems as family mastery decreased. This relationship is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Effect of family mastery on the association between early resistance to control and internalizing problems

Externalizing Problems

In the third multiple regression, which had externalizing problems as the dependent variable, there was a significant interaction between the temperament dimension of difficultness and the family adaptive resource of family mastery (F1,273 = 5.91, p = 0.0157). The pattern with externalizing problems was similar to the ones for total and internalizing problems in that difficultness had a positive association with externalizing behavior in families with low family mastery but not in families with high family mastery. For a family mastery score of 1, the standardized beta was 0.32 (p = 0.0204). For a family mastery score of 3, the standardized beta was −0.14 (p = 0.1536). The moderating effect of family mastery is reflected in the weakening of the association between difficultness and externalizing problems in families with high mastery compared to families with low mastery. This is similar to the relationship between difficultness and total behavior problems shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

The primary focus of the study was to evaluate our model that proposed associations among a child’s early temperament, family adaptive resources, and later behavior problems. All three temperament dimensions–difficultness, unadaptability, and resistance to control–were correlated with total and internalizing behavior problems in our sample. In addition, difficultness and resistance to control, though not unadaptability, were positively correlated with externalizing behavior problems. The pattern of results converges with previous studies’ findings [13]. Difficultness (negative emotionality) predicts both internalizing and externalizing problems at approximately equal levels; resistance to control (unmanageability, perhaps an early marker of impulsivity) predicts externalizing problems more strongly than internalizing problems; and unadaptability (novelty distress, perhaps an early marker of anxiety) predicts internalizing problems more strongly than externalizing problems. Early temperament appears to be an important risk factor that may help explain why some children develop behavior problems and others do not. Negative temperamental characteristics seen in infancy, including those classified as difficult, resistant, or maladaptive, are risk factors for behavior problems at the time of seizure onset later in childhood. Infants who have difficult and resistant temperaments may be at a relatively greater risk for both internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Because internalizing behavior problems are the most common in children with epilepsy [4, 7, 28, 43], it is especially important to identify factors that might predispose children with seizures to internalizing problems.

The relationship between the temperament dimension of difficultness and behavior problems was moderated by the family environment, specifically the family’s adaptive resource of mastery. When children who were characterized as being difficult as infants were raised in less cooperative and organized families, they were at greater risk for total, internalizing, and externalizing behavior problems than children who were easier as infants. These findings suggest that infants who are fussy, irritable, and easily upset might benefit from being reared in a family that has a strong sense of control over events. Families with high mastery do not have trouble accomplishing tasks; they plan ahead, have direction, and believe that each family member contributes equally. It might be that an organized family environment provides children with more difficult temperaments with needed routine and structure, which in turn lessens the behavioral risk associated with this problematic temperament.

Two of the three temperament characteristics evaluated in the present study were moderated by the family’s adaptive resource of family mastery, but only one in the anticipated direction. In children with difficult early temperaments, family mastery served as a protective factor against the possible influence of negative temperament on behavior problems. On the other hand, children who were high on resistance to control showed more internalizing behaviors when they lived in more organized families than when they lived in less organized families. Although this result was not initially predicted, a possible explanation consistent with our initial hypothesis is that family resources would moderate the relationship between temperament and behavior in an adaptive way. Although fewer internalizing problems (e.g., less anxiety) could be viewed as positive in terms of behavioral adjustment, an increase in anxiety might be adaptive in children whose temperament is high in resistance to control. A resistant-to-control temperament can be characterized by impulsivity, reward-seeking, and non-compliance. When these children live in families that have less organization, direction, and control over events, as well as an inability to learn from past mistakes (i.e., has low mastery), they may fail to develop appropriate signs of anxiety that may be adaptive for inhibiting certain problematic behaviors. When these headstrong children live in families who have higher mastery, they will most likely experience anxiety as their parents seek to bring the child’s impulsive behaviors under control. In other words, resistant infants may benefit from living in more organized family environments and their increase in internalizing symptoms might result because the family environment is forcing them to curb their non-compliant behavior.

Our findings lend support to Austin’s model of family adjustment to childhood seizures [30] by showing the influence of difficult temperament and family factors on negative outcomes. Austin’s model outlines characteristics at seizure onset, describes variables during the adaptation process, and describes how both of these contribute to child outcomes. The results of our study further elaborate this theoretical framework by showing support for modified models (Figure 1-B) that include the interaction of specific family and early child characteristics with later behavior problems. Early behavior problems in children with epilepsy are one of the best predictors of behavior problems later in childhood [9]. Therefore, it is important that we identify children with behavior problems at the onset of seizures to try to prevent future behavioral maladjustment. Implementing interventions at the family level may be necessary to change the course of the child’s behavior problems.

Children with seizures have been shown to fare worse in terms of the quality of the parent-child relationship [44, 45]. A negative parent-child relationship has been shown to be related to child behavior problems [46], as well as to child psychopathology [44]. Child temperament might be an influencing variable. For example, an early difficult temperament in the child could negatively influence the early parent-child relationship, which could be further strained by the stress associated with new-onset seizures in children [30]. Other variables of parent-child interaction, such as encouragement of child autonomy and parent confidence in managing child discipline, have been associated with an improvement in behavior problems over time [6]. Evaluating parent-child variables and their interaction with temperament, the family environment, and behavior may prove useful in developing interventions focused not only on the family environment, but also on the parent-child relationship.

A number of interventions tailored to specific child temperaments are currently being researched and implemented. Experiments by Cameron and Rice (1986) illustrate how temperament-based anticipatory guidance can be used as an effective preventative clinical tool. The guidance materials help parents to understand and cope with their child’s behavioral issues related to his or her temperament [47]. These techniques focus on parent-child interaction and are currently being used in a variety of settings [48]. Research on parent programs for inner-city children encourages approaching challenging children in a manner that acknowledges the child’s temperament but encourages compliance [49]. For example, parents of children who are high in negative reactivity are encouraged to selectively ignore the child’s comments [49]. Interventions that align with the strategies used by current effective treatments should be attempted with children with seizures and behavior problems. Standard parent training seeks to improve a parent’s mastery and sense of control over events. Incorporating this type of parent training with strategies that take into account the child’s temperament would prove most beneficial to the families.

The present study’s results on resistant-to-control infants must be replicated to further understand the moderating effect of the family environment. Several child and family variables may influence this specific temperament dimension and its association with behavior, making it difficult to provide specific intervention strategies. Preliminary data suggest that children with high resistance to control show stronger associations between disrupted sleep and poor adjustment in preschool compared to temperamentally manageable children [50]. Further study of the factors that affect the association between a resistant temperament and behavior is warranted before preventative clinical practices can be suggested.

Other variables in Austin’s model may moderate the association between temperament and negative outcomes. Further study is needed to investigate variables such as other family stressors, child seizure characteristics, and child cognitive functioning as moderators of behavior problems. Because children with seizures show problems in cognitive ability [36, 51, 52], future studies might investigate relationships among cognitive functioning, temperament, and behavior problems.

Previous research has identified neurobiological, pharmacological, and psychosocial factors as the three important risk factors in the development of behavioral difficulties [32]. One study evaluated many of these factors and found that family-related factors, specifically family cohesion and conflict, were the factors most associated with negative CBCL outcomes (second to a history of prolonged seizures) [31]. The findings of that study, along with the present findings on the behavioral implications of child temperament dimensions and family characteristics, encourage an investigation of the individual psychological and social components of negative behavioral development.

The study has some limitations. The retrospective nature of the temperament measure inherently presents a limitation. Parents’ recollections will not perfectly represent their perceptions of temperament in infancy, but the evidence suggests that what they recollect later corresponds to what they would have reported at the time [37]. Even if it is assumed that it is a totally concurrent rating of temperament, this would still be of value. The child’s current behavior may influence a parent’s perception of early temperament and result in a negative bias. However, given the fact that we used teacher reports of behavior, such bias would have minimal impact on the findings of the study, especially on findings involving interactions between temperament and family variables on adjustment in school.

Clinical Implications

The high prevalence of behavior problems in children with epilepsy is of concern to parents and healthcare professionals alike. Early temperament, which is multi-dimensional and the effects of which can be moderated by the family environment, is one index that can be used to identify children with new-onset seizures who are at increased risk for future behavioral problems. Children with a first-recognized seizure who present with a negative early temperament should be assessed for behavior problems and possible intervention. It is important to assess specific temperament dimensions because the family environment may influence certain dimensions differently. Specific family adaptive resources, such as family mastery, are important factors to consider when evaluating a child’s risk for future behavior problems. Assessment of this specific family variable, and its interaction with temperament characteristics, will allow health professionals to identify families and children who are at the highest risk for poor behavioral outcomes. Effective prevention and treatment programs can be implemented in the home and school setting to lessen the likelihood of this maladjustment. Interventions aimed at enhancing the family environment may prove relatively more beneficial to children with particularly difficult temperamental tendencies, thus reducing the likelihood of a child’s negative behavioral adjustment. It is important to identify multiple risk factors that, interactively, correlate with behavior problems. It is unlikely that temperament, alone, will lead to the development of behavior problems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant PHS R01 NS22416 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to J.K.A. We acknowledge assistance from B. Hale as well as the Epilepsy and Pediatric Neurology Clinics at Riley Hospital, Indiana University Medical Center, and the Department of Neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. We thank A. McNelis for coordinating data collection, P. Dexter for editorial comments, and P. Buelow for editorial assistance. Address correspondence to Dr. J.K. Austin at Indiana University School of Nursing, 1111 Middle Dr, NU492, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5107. E-mail: joausti@iupui.edu

Footnotes

There were significant positive correlations between each of the teacher reports of behavior problems and the parent reports on the CBCL (all p < .0001).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hauser WA. The prevalence and incidence of convulsive disorders in children. Epilepsia. 1994;35 (Suppl 2):S1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb05932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodenburg R, Stams GJ, Meijer AM, Aldenkamp AP, Dekovic M. Psychopathology in children with epilepsy: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(6):453–68. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott D, Siddarth P, Gurbani S, Koh S, Tournay A, Shields WD, et al. Behavioral disorders in pediatric epilepsy: unmet psychiatric need. Epilepsia. 2003;44(4):591–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.25002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin JK, Dunn DW, Caffrey HM, Perkins SM, Harezlak J, Rose DF. Recurrent seizures and behavior problems in children with first recognized seizures: a prospective study. Epilepsia. 2002;43(12):1564–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.26002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin JK, Dunn DW, Huster GA. Childhood epilepsy and asthma: changes in behavior problems related to gender and change in condition severity. Epilepsia. 2000;41(5):615–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin JK, Dunn DW, Johnson CS, Perkins SM. Behavioral issues involving children and adolescents with epilepsy and the impact of their families: recent research data. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5 (Suppl 3):S33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keene DL, Manion I, Whiting S, Belanger E, Brennan R, Jacob P, et al. A survey of behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6(4):581–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott S, Mani, S, Krishnaswami, S A population-based analysis of specific behavior problems associated with childhood seizures. J Epilepsy. 1995;8:110–118. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oostrom KJ, van Teeseling H, Smeets-Schouten A, Peters AC, Jennekens-Schinkel A. Three to four years after diagnosis: cognition and behaviour in children with ‘epilepsy only’. A prospective, controlled study. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 7):1546–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin JK, Harezlak J, Dunn DW, Huster GA, Rose DF, Ambrosius WT. Behavior problems in children before first recognized seizures. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):115–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrin EC, Ramsey BK, Sandler HM. Competent kids: children and adolescents with a chronic illness. Child Care Health Dev. 1987;13(1):13–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1987.tb00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates JE, Wachs TD. Temperament: individual differences at the interface of biology and behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. Handbook of child psychology. In: Damon W, editor. Social, emotional, and personality development. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 105–176. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates JE, Wachs TD, VandenBos GR. Trends in research on temperament. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46(7):661–3. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.7.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson HW. Infant temperamental factors as predictors of problem behavior and IQ at age 5 years: Interactional effects of biological and social risk. Child Study J. 1999;29(3):207–226. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasserman RC, DiBlasio CM, Bond LA, Young PC, Colletti RB. Infant temperament and school age behavior: 6-year longitudinal study in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1990;85(5):801–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerin DW, Gottfried, AW, Thomas, CW Difficult temperament and behaviour problems: A longitudinal study from 1.5 to 12 years. Int J Behav Dev. 1997;21(1):71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahr LK, El-Haddad, A Temperament and chronic illness in Egyptian children. Int J Intercultural Rel. 1998;22(4):453–465. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marino BL, Lipshitz M. Temperament in infants and toddlers with cardiac disease. Pediatr Nurs. 1991;17(5):445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SP, Ferrara A, Chess S. Temperament of asthmatic children. A preliminary study J Pediatr. 1980;97(3):483–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carey WB, McDevitt SC, Baker D. Differentiating minimal brain dysfunction and temperament. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1979;21(6):765–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1979.tb01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christodoulou C, Deluca J, Johnson SK, Lange G, Gaudino EA, Natelson BH. Examination of Cloninger’s basic dimensions of personality in fatiguing illness: chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):597–607. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winblad S, Lindberg C, Hansen S. Temperament and character in patients with classical myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM-1) Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15(4):287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boekaerts M, Roder, I Stress, coping and adjustment in children with chronic disease: A review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 1999;21(7):311–337. doi: 10.1080/096382899297576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cadman D, Boyle M, Szatmari P, Offord DR. Chronic illness, disability, and mental and social well-being: findings of the Ontario Child Health Study. Pediatrics. 1987;79(5):805–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M, Sobol AM. Chronic conditions, socioeconomic risks, and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1990;85(3):267–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallander JL, Hubert NC, Varni JW. Child and maternal temperament characteristics, goodness of fit, and adjustment in physically handicapped children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1988;17(4):336–344. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn DW, Austin JK, Caffrey HM, Perkins SM. A prospective study of teachers’ ratings of behavior problems in children with new-onset seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(1):26–35. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn DW, Austin JK, Huster GA. Behaviour problems in children with new-onset epilepsy. Seizure. 1997;6(4):283–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin JK. A model of family adaptation to new-onset childhood epilepsy. J Neurosci Nurs. 1996;28(2):82–92. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCusker CG, Kennedy PJ, Anderson J, Hicks EM, Hanrahan D. Adjustment in children with intractable epilepsy: importance of seizure duration and family factors. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44(10):681–7. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermann BP, Whitman S. Neurobiological, psychosocial, and pharmacological factors underlying interictal psychopathology in epilepsy. Adv Neurol. 1991;55:439–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin JK, Risinger MW, Beckett LA. Correlates of behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1992;33(6):1115–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huberty TJ, Austin JK, Harezlak J, Dunn DW, Ambrosius WT. Informant Agreement in Behavior Ratings for Children with Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1(6):427–435. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Touliatos J, Lindholm BW. Congruence of parents’ and teachers’ ratings of children’s behavior problems. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1981;9(3):347–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00916839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Long CG, Moore JR. Parental expectations for their epileptic children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1979;20(4):299–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1979.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Dev Psychol. 1998;34(5):982–95. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates JE, Freeland CA, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Dev. 1979;50(3):794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Achenbach TM. Manual for the teacher’s report form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 & 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCubbin HI, Thompson AI. Family assessment inventories for research and practice. 2. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1991. Family Stress Coping and Health Project. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Efron B, Tibshirani R. 1st CRC Press reprint ed. Boca Raton, Fla.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: 1998. An introduction to the bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hermann BP, Whitman S, Hughes JR, Melyn MM, Dell J. Multietiological determinants of psychopathology and social competence in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1988;2(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodenburg R, Marie Meijer A, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family predictors of psychopathology in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(3):601–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodenburg R, Meijer AM, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family factors and psychopathology in children with epilepsy: a literature review. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6(4):488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pianta RC, Lothman DJ. Predicting behavior problems in children with epilepsy: child factors, disease factors, family stress, and child-mother interaction. Child Dev. 1994;65(5):1415–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cameron JR, Rice DC. Developing anticipatory guidance programs based on early assessment of infant temperament: two tests of a prevention model. J Pediatr Psychol. 1986;11(2):221–34. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/11.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cameron JR, Rice DC. Children’s Bureau Express. 2002. Temperament assessments seen as effective parenting and child abuse prevention tool. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McClowry S, Galehouse P. Planning a temperament-based parenting program for inner-city families. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2002;15(3):97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2002.tb00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bates JE, Viken RJ, Williams N. Temperament as a moderator of the linkage between sleep and preschool adjustment. Poster presentation at meeting of Society for Research in Child Development; Tampa, FL.. April, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Austin JK, Huberty TJ, Huster GA, Dunn DW. Academic achievement in children with epilepsy or asthma. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40(4):248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Austin JK, Huberty TJ, Huster GA, Dunn DW. Does academic achievement in children with epilepsy change over time? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41(7):473–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]