Abstract

This study evaluated whether acute ethanol pretreatment potentiates Fas-mediated liver injury and if oxidative stress and CYP2E1 play a role in any enhanced hepatotoxicity. There were 3-fold increases of transaminases and more extensive apoptotic necrosis of hepatocytes, and focal hemorrhages of the hepatic lobule in mice treated with Jo2 plus ethanol compared to saline control or to mice treated with Jo2 or ethanol alone. CYP2E1 catalytic activity and protein were increased 2-fold by the acute ethanol pretreatment. There were 2- and 2.5-fold increases of caspase-8 and caspase-3 activity, and 1.6-fold increases of apoptotic positive cells in the Jo2 Fas plus acute ethanol group compared to the Jo2 alone group. Levels of TNF-α, malondialdehyde, 4- hydroxynonenal, protein carbonyl formation, 3-nitrotyrosine protein adducts, and inducible nitric oxide synthase were increased in the Jo2 plus ethanol group. The enhanced hepatotoxicity of Jo2 plus ethanol and the elevated oxidative stress and TNF levels were lower in CYP2E1 knockout mice compared to wild-type mice expressing CYP2E1 but higher than saline controls. Toxicity also declined in mice treated with gadolinium chloride, an inhibitor of the inducible nitric oxide synthase or the antioxidant, N-acetyl-L-cysteine. These data indicate acute ethanol pretreatment is capable of elevating hepatic apoptosis and liver injury induced by Jo2 Fas agonistic antibody. The enhanced hepatotoxicity involves increased oxidative and nitrosative stress, and appears to be mediated by CYP2E1-dependent but also CYP2E1-independent mechanisms.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450 2E1, Jo2 agonistic antibody, Hepatotoxicity, Apoptonecrosis, Nitrosative stress, Oxidative stress

Introduction

Alcohol-induced liver injury can be linked to oxidative stress and increased production of reactive oxygen species [1,2]. Many pathways have been suggested to contribute to the ability of ethanol to induce a state of oxidative stress, which involve increases of lipid peroxidation and protein oxidative and nitrosative stress and a decrease in hepatic antioxidant defense [3–5]. The mechanisms by which alcohol causes liver injury are still not clear. Less mechanistic information is available with respect to acute alcoholic liver injury even though binge alcohol drinking is frequently more common than chronic alcoholism and also a risk factor to other potential liver diseases. Cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) activates many toxicologically important substrates including ethanol [6–8]. Induction of CYP2E1 by ethanol is a central pathway by which ethanol generates a state of oxidative stress and causes hepatotoxicity [9–14]. It was found that pathological changes of ethanol-induced liver injury correlate with CYP2E1 levels and elevated microsomal lipid peroxidation [15–17].

Morphological studies have shown that hepatocyte apoptosis occurs in rat or mouse liver after chronic ethanol feeding [18,19]. Potential mechanisms of ethanol-induced liver apoptosis include Fas ligand (FasL) expression, increased cytokine activity and /or oxidative stress [20–22]. The Fas/Fas ligand system may play a central role in ethanol-induced hepatic apoptosis [23–25]. Galle, et al [21] showed up-regulation of Fas ligand mRNA expression in hepatocytes of alcohol-damaged liver. However, Deaciuc, et al [26] found no change in Fas ligand mRNA expression after chronic ethanol feeding for 7 weeks. Apoptosis induced by low concentrations of ethanol in HepG2 cells was associated with Fas-receptor activation and subsequent caspase-8 and caspase-3 activation [27]. Minana, et al [24] showed that ethanol and acetaldehyde caused apoptosis in hepatocytes after chronic ethanol feeding and that acetaldehyde elevated Fas ligand levels; they suggested that Fas may play a role in ethanol-induced apoptosis. However, Nakayama, et al [28] reported that in HepG2 cells ethanol-induced apoptosis was not mediated via Fas or TNF-α receptors, and that ethanol did not up-regulate Fas expression. Hepatocytes were recently shown to express both Fas and Fas ligand which can induce death of other co-cultured cells, and it is interesting to speculate that apoptosis by autocrine or paracrine mechanisms involving Fas may play a role in alcohol-induced liver injury [29]. It is unknown whether acute ethanol treatment can synergize with Fas to promotes apoptosis or injury in hepatocytes. We speculated that elevated oxidative or nitrosative stress produced via the induction of CYP2E1 by ethanol pretreatment primes or sensitizes the liver to Fas such that synergism and potentiation of liver injury occur. Indeed, pyrazole treatment to induce CYP2E1 potentiated Fas-mediated liver injury via elevated oxidative and nitrosative stress [30].

Materials and Methods

Experimental models and Treatments

The animal study was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care Committee of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and fulfilled the guidelines of National Institute of Health for the humane use of animal subjects. Male C57BL/6 mice, weighing 18–22 g, at 6–8 weeks of age, were purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratory (Boston, MA). All mice were divided into groups which received either saline (Sal group, n=6), Jo2 alone (Jo2 group, n=6), ethanol alone (Eth group, n=8) or Jo2 following ethanol pretreatment (Eth/Jo2 group, n=8). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with ethanol (Pharmaco, Brookfield, CT), 2.5 g/kg body weight (35% solution vol:vol), twice a day for 3 days. Two hour after the last dose of ethanol, the mice were administered intraperitoneally either saline or agonistic Jo2 hamster anti-mouse Fas monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), 0.2 μg/g body weight. At 8 hours after administration of Jo2 or saline, the mice were sacrificed and serum and liver samples were collected. In some experiments on the time course of injury, mice were sacrificed 2, 4 and 8 hours after administration of Jo2 or saline. Concentration curves for ethanol and Jo2 and time course experiments were carried out in preliminary experiments to establish the above model showing potentiation of Jo2 toxicity by acute ethanol treatment in the absence of toxicity by Jo2 alone or ethanol alone.

Serum Transaminases and TNF-α Assay

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were assayed using a diagnostic kit (ThermoDMA, Louisville, CO). The serum TNF-α level was assayed using a mouse TNF-α ELISA kit (Pierce Biotichnology, Rockford, IL).

Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Observation

Small pieces of liver tissue were fixed and processed into paraffin sections for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and light microscopic observation. Morphological changes were observed by two pathologists who were blinded from the experimental information. All changes of degeneration, apoptosis, necrosis and hemorrhage were graded as none (0), mild (<25%), moderate (25–50%), and severe (>75%). Immunohistochemical staining was performed by using the immunoCruz rabbit ABC Staining System Kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) for CYP2E1 with rabbit-anti-CYP2E1 antibody (1:200), provided by Dr. Jerome Lasker, Hackensack Biomedical Research Institute; for 4-HNE (4-hydroxynonenal) with rabbit-anti-4-HNE antibody (1:100) (EMD Bioscience, La Jolla, CA). The evaluation of a specific positive reaction was marked as negative (−), weakly positive (+), moderately positive(++), and strongly positive (+++).

Cytochrome P450 2E1 Activity

CYP2E1 activity was measured in liver microsome fractions by the spectrophotometric analysis at 546 nm of the oxidation of p-nitrophenol to p-nitrocatechol in the presence of NADPH and oxygen [31]. The protein concentration of the different fractions was determined using a protein assay kit based on the Lowry assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Lipid Peroxidation, Protein Carbonyl, GSH and Catalase Assay

The production of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), expressed as malondialdehyde (MDA) equivalents, was assayed in liver mitochondria and liver homogenate fractions by the spectrophotometric analysis at 535 nm of the formation of thiobarbituric acid-reactive components [32]. Protein carbonyl adducts were assayed in liver homogenates using 20 μg of protein samples and the OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). The DNP-derivatized protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot as described above. Reduced glutathione (GSH) was analyzed in liver tissue homogenates by a fluorescence assay with the proluminescent substrate o-phthalaldehyde. Catalase activity was assayed by measuring the decomposition of H2O2 at 240 nm [33].

Western Blot Analysis

The levels of CYP2E1, FAS receptor, iNOS, MPO (myeloperoxidase) and 3-NT (3-nitrotyrosine) protein adducts in 50 μg of protein samples from freshly prepared microsome, cytosol or homogenate fractions were determined by Western blot analysis with anti-CYP2E1 (1:10000), anti-FAS (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), anti-iNOS (1:500), anti-MPO (1:1000) (PD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and anti-3-NT protein adducts antibody (1:200) (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA), respectively. All specific bands of proteins detected by Western blot were quantitated with the Automated Digitizing System (ImageJ gel programs, version 1.34S, National Institute of Health).

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-Mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling and Caspase Activities Assay

Apoptosis or DNA fragmentation was assessed via terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay using the ApopTag in situ apoptosis detection kit (Serological Corp., Atlanta, GA). Under light microscopy the numbers of TUNEL positive cells were counted per high-powered field (400× magnification) with 20 random fields counted per liver. Caspase-8 and caspase-3 activities were determined in liver tissue homogenates by measuring proteolytic cleavage of the proluminescent substrates Z-IETD-AFC or AC-DEVD-AMC (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). The fluorescence was determined based on the amount of released AFC (caspase-8, λex=400, λem=505) or AMC (caspase-3, λex=380, λem=460). The results were expressed as arbitrary units of fluorescence (AUF) per milligram of protein.

Treatment with Potential Protectants against Jo2 plus Ethanol Toxicity

Male C57BL/6 mice, weighing 20–23 g, were divided into groups which received either saline (Sal group, n=4) or Jo2 following ethanol pretreatment (Eth/Jo2 group, n=8) or Jo2 following ethanol pretreatment plus potential protectants: gadolinium chloride (50 mg/kg body weight) (Eth/Jo2/GdCl3 group, n=10); pentoxifylline (100mg/kg) (Eth/Jo2/PTX group, n=10); N-[(3-aminomethyl) benzyl] acetamidine (10 mg/kg body weight) (Eth/Jo2/1400W group, n=10) or N-acetyl-L-cysteine (150 mg/kg body weight) (Eth/Jo2/NAC group, n=10), respectively. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with the above potential protectants 30 min prior to Jo2 treatment. At 10 hours after administration of Jo2 or saline, mice were sacrificed for collecting serum and liver tissue for ALT, TNF-α assay and pathological observation. GdCl3 was injected IP since this mode of administration was effective in preventing concanavalin- or endotoxin-induced liver injury [34,35].

Jo2 Toxicity in CYP2E1-Null Mice

CYP2E1 knockout (−/−) mice, Cyp2e1tm1Gonz, weighing 16–20 g at 6–7 weeks of age, were kindly provided by Dr. Frank Gonzalez, National Institutes of Health and were bred in the animal center of Mount Sinai School of Medicine. The wild-type (CYP2E1+/+) 129/SV mice, weighing 16–20 g at 6–7 weeks of age, were purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratory (Boston, MA). The CYP2E1 −/− (KO, n=10) and +/+ (WT, n=10) mice received Jo2 plus ethanol as described above for the C57BL/6 mice. Before performing this experiment, we repeated the previous results (C57BL/6 model) in 129/SV wild-type mice treated with Jo2 plus ethanol so as to characterize the potentiation of Jo2 toxicity by ethanol in the 129/SV strain. Another group of CYP2E −/− (KO, n=6) and +/+ (WT, n=6) were injected intraperitoneally with a higher concentration of Jo2 alone, 0.5 μg/g body weight for 4 hours. Serum and liver tissue fractions were collected after either 2, 4 or 8 hours (Jo2 plus ethanol experments) or 4 hours (Jo2 alone model).

Statistical Analysis

Values reflect means±SEM. One-way ANOVA (subsequent post-hoc comparisons) analysis was performed by Excel Data Analysis toolpac. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The number of mice is indicated in the Legend to Figures.

Results

Serum Transaminases and Liver Pathological Changes

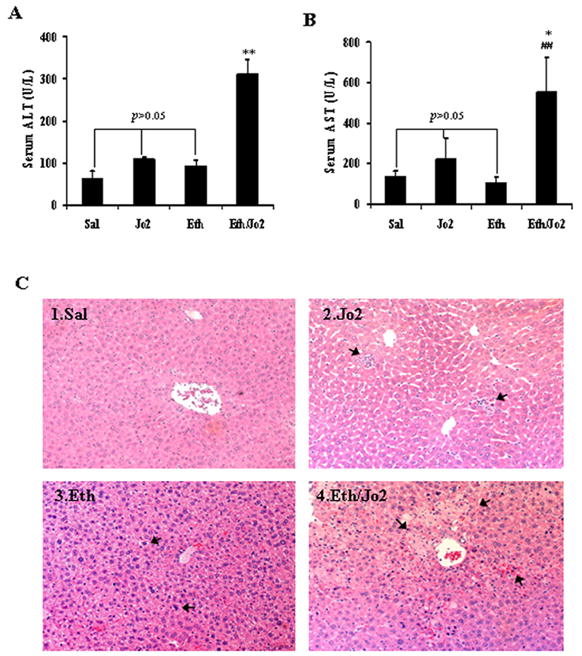

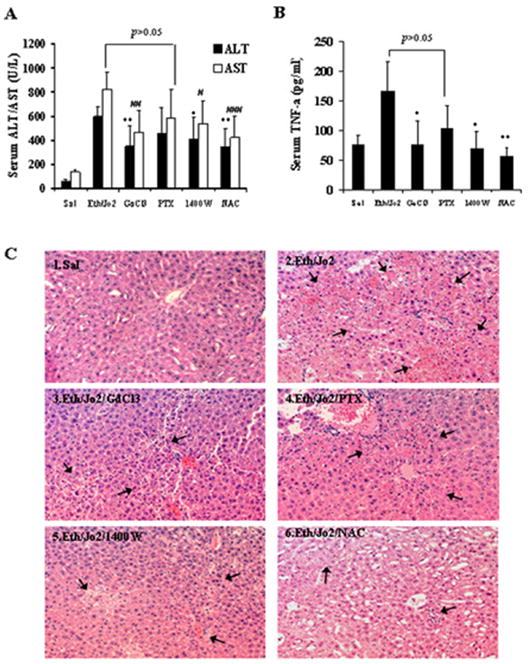

In the Eth/Jo2 group, serum ALT and AST activities were significantly higher than that in the Jo2 or Eth alone group. In the Jo2 or Eth alone group, serum ALT and AST activities were slightly but not significantly higher than that in the Sal (Fig.1A, 1B). Severe pathological changes were observed in the Eth/Jo2 group in which many hepatocytes displayed massive acidophilic necrosis or apoptosis, cytolysis and focal infiltration of inflammatory cells in the central zone of the hepatic lobule (Fig.1C4). There was only moderate or mild pathological changes in hepatocytes including limited necrosis in the Jo2 group (Fig.1C2) and vacuolar degeneration in the Eth group (Fig.1C3). In the Sal group, there were no obvious pathological changes (Fig.1C1).

Fig.1.

Levels of serum ALT, AST and histopathological changes of liver after treatment with Jo2 plus ethanol. (A) serum ALT and (B) serum AST. (C1) Liver showed normal morphology (HE×200). (C2) Liver showed slightly sinusoid dilation and congestion, limited acidophilic degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes in the centrilobular zone (arrows, HE×200). (C3) Liver showed slight congestion and large amounts of microvesicular fatty degeneration (arrows, HE×200). (C4) Liver showed extensive acidophilic necrosis, focal hemorrhages, cytolysis and focal infiltration of inflammatory cells in the central zone of the hepatic lobule (arrows, HE×200). Data are the mean±SEM for 6–8 mice. ** and ## compared to Jo2 or to Eth groups, p<0.01. * significantly different from the Jo2 group, p<0.05

Caspase Activities and TUNEL Analysis

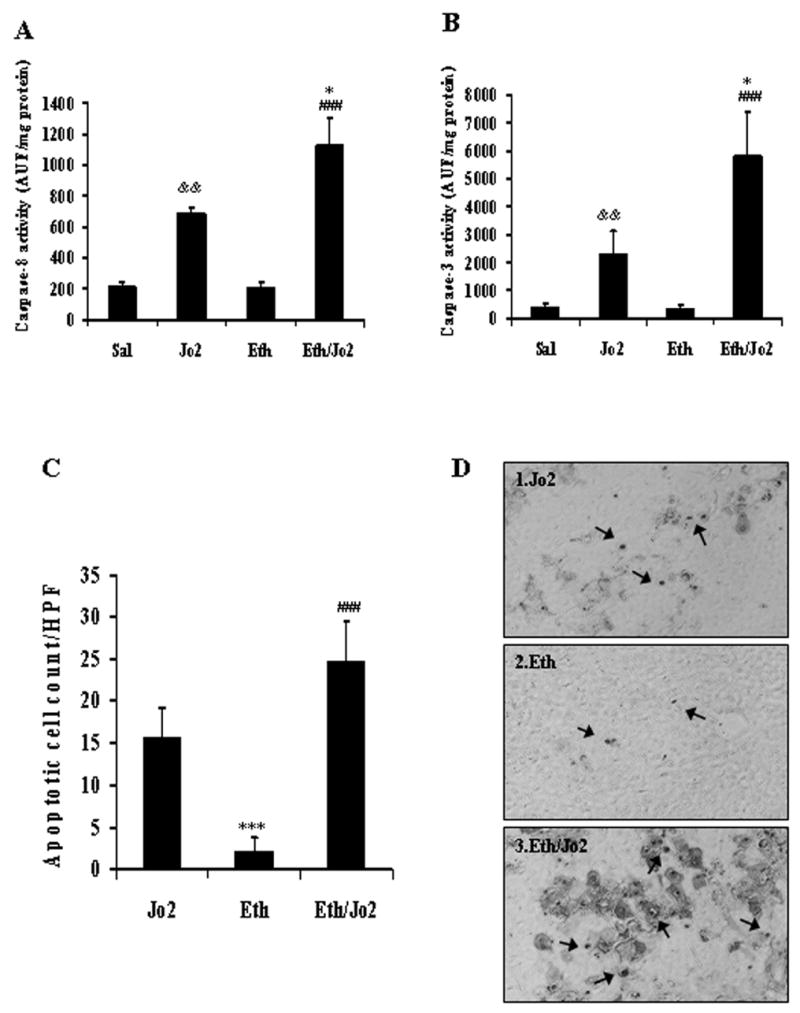

To evaluate changes in apoptosis, caspase activity and TUNEL staining were determined. The activity of caspase-8 or caspase-3 was significantly higher in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the other 3 groups (Fig.2A,2B). Ethanol alone had no effect on activity of caspase-8 or 3, however, Jo2 alone increased these activities, although not to the same extent as the Jo2 plus ethanol treatment (Fig.2A,2B). TUNEL results showed that there were many hepatocytes with positive staining nuclei in either the Eth/Jo2 or Jo2 group; highest levels of hepatocytes with TUNEL-positive nuclei were found in the Eth/Jo2 group (Fig.2C, 2D1,2D3). There were just a limited number of hepatocytes with TUNEL-positive nuclei in the Eth group (Fig.2C, 2D2) and no TUNEL staining in the saline controls (data not shown).

Fig.2.

Caspase-8 and caspase-3 activities and TUNEL analysis. The fluorescence associated with cleavage of the proluminescent substrates Z-IETD-AFC and AC-DEVD-AMC was determined with a spectrofluorometer based on the amount of released AFC (caspase-8, λex=400, λem=505) or AMC (caspase-3, λex=380, λem=460). The results were expressed as arbitrary units of fluorescence per milligram of protein. (A) Caspase-8 activity in liver tissue. (B) Caspase-3 activity in liver tissue. Results are from 6–8 mice in each group. (C) Numbers of apoptotic cells per high-powered field (HPF) by TUNEL assay. Results from 3 Jo2 treated, 3 Eth treated and 4 Eth/Jo2 treated mice are shown. (D) Apoptosis was assessed via TUNEL assay using the ApopTag in situ apoptosis detection kit. * significantly different from the Jo2 group, p<0.05. ### significantly different from the Eth group, p<0.001. && significantly different from the Sal group, p<0.01. *** significantly different from the Jo2 group, p<0.001.

Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress

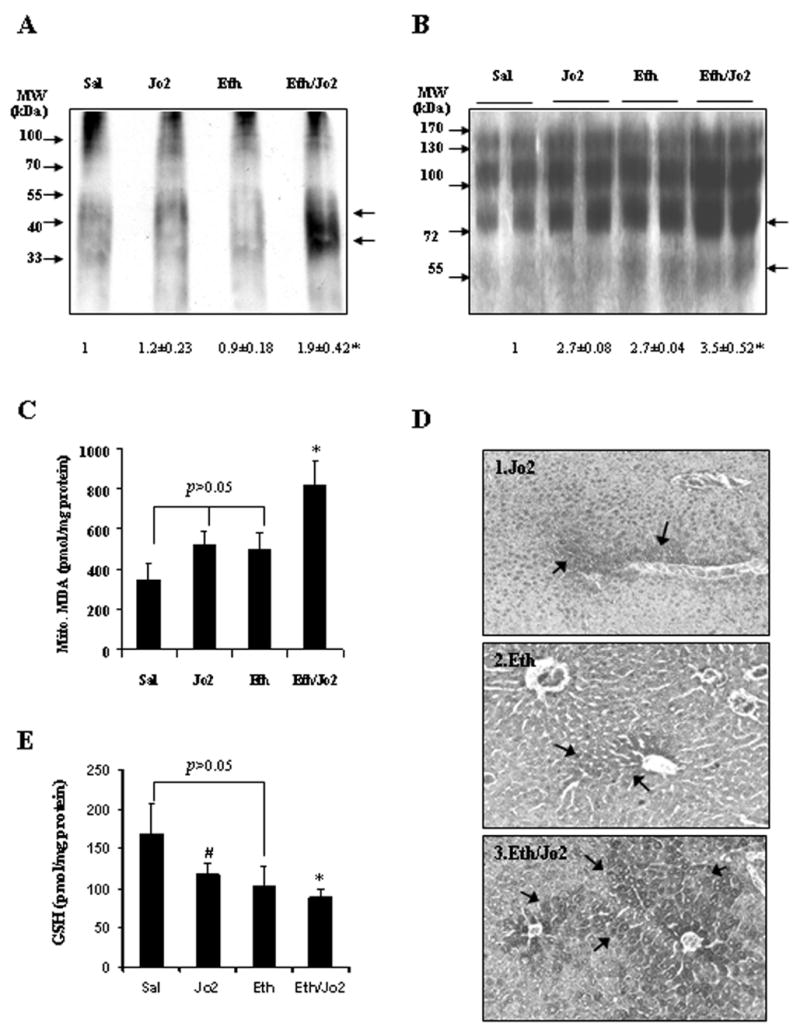

Experiments were carried out to evaluate whether the enhanced hepatotoxicity found in the Eth/Jo2 group was associated with an elevated oxidative/nitrosative stress. The level of protein carbonyl adducts was 1.9-fold higher in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Sal, Jo2 or Eth group. There was no significant elevation of protein carbonyl levels in the Jo2 or Eth alone group (Fig.3A). Levels of 3-NT protein adducts were 3.5-fold higher in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Sal group. There were also 2.7-fold higher levels of 3-NT protein adducts in the Jo2 or Eth alone group compared to the Sal group. Levels of 3-NT protein adducts were slightly but not significantly higher in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Eth or Jo2 alone groups (Fig.3B). MDA, as one index of lipid peroxidation, was significantly higher in the mitochondrial fractions isolated from the livers of the Eth/Jo2 group than that in the other groups (Fig.3C). The expression in situ of 4-HNE was mainly found in cytoplasm of hepatocytes in the centrilobular zone of the liver. The 4-HNE levels were highest in the Eth/Jo2 group (+++) (Fig.3D3); smaller increases were also found in the Jo2 (++) (Fig.3D1) and Eth group (+) (Fig.3D2). Total GSH levels decreased in the Jo2 (−29%), Eth (−39%) and Eth/Jo2 (−48%) groups compared to the Sal group. GSH levels were lowest in the Eth/Jo2 group, but there were no significant differences in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Eth group (Fig.3E). Catalase activity did not change in the Jo2, Eth or Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Sal group (data not shown).

Fig.3.

Protein carbonyl, 3-NT protein adducts, lipid peroxidation and GSH levels. (A) The protein carbonyl level was assayed in liver homogenates using 20 μg of protein samples, and the OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit as described in Materials and Methods. * significantly different from the Sal, Jo2 or Eth group, p<0.05. (B) The levels of 3-NT protein adducts in 50 μg of protein samples from freshly prepared homogenate fractions were determined by Western blot analysis. * significantly different from the Sal group, p<0.05. (C) The production of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), expressed as malondialdehyde (MDA) equivalents, was assayed in liver mitochondria by the spectrophotometric analysis at 535 nm of the formation of thiobarbituric acid-reactive components. * significantly different from the Jo2 or the Eth group, p<0.05. (D) Immunohistochemical staining was performed by using the immunoCruz ABC Kit in paraffin section for 4-HNE with rabbit-anti-4-HNE antibody. Slides were visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and positive staining was reflected by the brownish yellow color in the centrilobular area. In each case, a negative control (non-immune serum) was used. (arrows, IHC×300). (E) Reduced glutathione (GSH) was analyzed in liver tissue homogenates by measuring fluorescence (λex=350, λem=420) as described in Materials and Methods. The concentration of GSH in the samples was calculated from a GSH standard curve. The results are expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein and are from 6–8 mice in each group. * significantly different from the Sal or the Jo2 group, p<0.05; # significantly different from the Sal group, p<0.05.

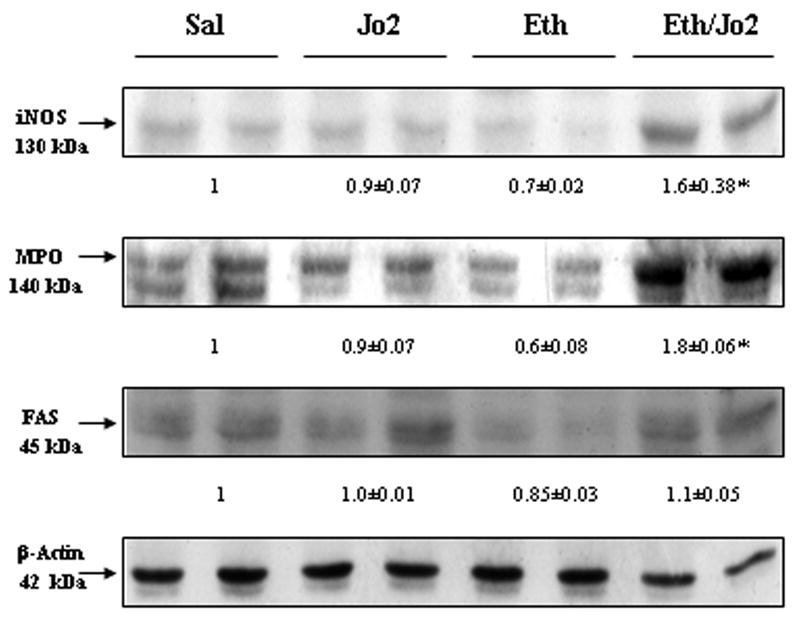

Protein Level of iNOS, MPO and FAS

Immunoblot analysis showed that there was an approximately 1.6-fold increase in the protein level of iNOS in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Sal control, while there were no changes in the Jo2 group or in the Eth group (Fig.4). Increases of 1.8-fold of MPO protein level were detected in the Eth/Jo2 group (Fig.4). The increase in MPO may result from infiltrating neutrophils in the damaged liver tissue as small increase in inflammatory cells were observed in liver of the Eth/Jo2 treated mice. We also observed an increase in iNOS by immunohistochemistry in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the other 3 groups (data not shown). The increased expression of iNOS was localized in the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes surrounding the central veins, the area where liver injury is observed (Fig.1C4) and in the infiltrating inflammatory cells, also localized in the necrotic, injury zone of the liver (data not shown). Protein levels of Fas receptor were the same in the Eth/Jo2 and Jo2 groups (Fig.4). Thus, the enhanced hepatotoxicity found in the Eth/Jo2 group is not due to altered levels of Fas.

Fig.4.

Levels of iNOS, MPO and FAS. The levels of iNOS, MPO and FAS receptor in 50 μg of protein samples from freshly prepared cytosol or homogenate fractions were determined by Western blot analysis. * significantly different from the Sal, Jo2 or Eth group, p<0.05. Typical blots are shown and arbitrary densitometric units of samples/β-actin ratio from four Sal, four Jo2 treated, four Eth treated and four Eth/Jo2 treated mice are shown below the blots.

Effect of Protectants

In view of the increases in iNOS and indices of oxidative and nitrosative stress, the effect of potential inhibitors of TNF-α production (GdCl3, pentoxyfylline), iNOS (1400W) or an antioxidant (NAC), in the Eth/Jo2 hepatotoxicity was evaluated. Levels of ALT and AST were significantly lower in the Eth/Jo2/GdCl3 group and the Eth/Jo2/NAC group compared to the Eth/Jo2 group (Fig.5A). 1400W also significantly protected against the Eth/Jo2 toxicity (Fig.5A). However, although a tendency for some protection, there were no significant differences in ALT and AST levels in the Eth/Jo2/PTX group compared to the Eth/Jo2 group (p>0.05) (Fig.5A). Serum TNF-α levels were elevated two-fold in the mice treated with Eth/Jo2 compared to the saline controls (Fig.5B). TNF-α was significantly lower in the Eth/Jo2/GdCl3, the Eth/Jo2/1400W and the Eth/Jo2/NAC group compared to the Eth/Jo2 group. Although lower, there was no significant difference in TNF-α levels in the Eth/Jo2/PTX group compared to the Eth/Jo2 group (Fig.5B). TNF-α levels in the Eth/Jo2/PTX group were not significantly different from the saline control values suggesting that the PTX treatment did lower the elevated TNF-α induced by Eth/Jo2, but because of considerable variability, this lowering was not significantly different from the Eth/Jo2 group. Pathological observation showed that a partial amelioration could be observed in liver of mice after pretreatment with GdCl3, 1400W or NAC followed by addition of Eth/Jo2, as the histopathology manifested as mainly mild or moderate apoptosis or necrosis, with moderate hepatocyte degeneration, limited hemorrhage and focal hepatocyte apoptotic necrosis (Fig.5C3,5C5,5C6) compared to the more severe pathological changes in the Eth/Jo2 group (Fig.5C2). There was no significant morphological amelioration in liver of mice treated with PTX (Fig.5C4).

Fig.5.

Protective role of various additives in Eth/Jo2-induced liver damage in mice. Male C57BL/6 mice received either saline, or Jo2 following ethanol pretreatment, or Jo2 following ethanol pretreatment plus either gadolinium chloride, pentoxifylline, N-[(3-aminomethyl) benzyl] acetamidine (1400W) or N-acetyl-L-cysteine as described in Materials and Methods. Serum was collected for transaminases assay and liver tissue for histopathological observation. (A) Serum ALT and AST activities. (B) Serum TNF-α contents. *, # compared to the Eth/Jo2 group, p<0.05. **, ## compared to the Eth/Jo2 group, p<0.01. ### compared to the Eth/Jo2 group, p<0.001. (C) Histopathological changes of liver with microscopic observation after HE staining. (arrows, HE×200).

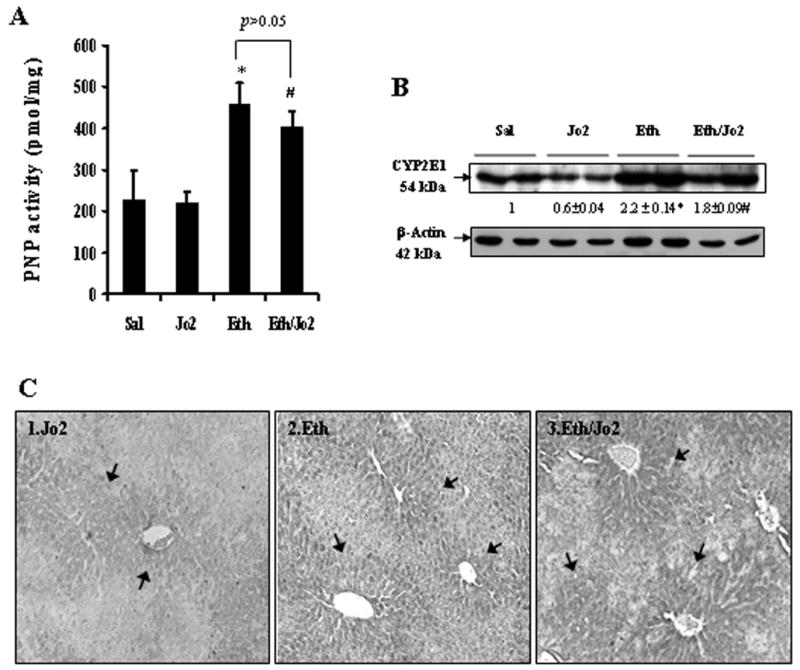

CYP2E1 Activity and Protein Level

An increase in the levels of CYP2E1 may play a role in the potentiated toxicity found in the Eth/Jo2 group. There was a 2-fold increase in PNP activity in the Eth group compared to the Sal control and in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Jo2 group (Fig.6A). Increases of 2.2-fold of CYP2E1 protein expression were detected by western blot analysis in the Eth group compared to the Sal control, while the level in the Eth/Jo2 group was 3-fold higher than the CYP2E1 level in the Jo2 alone group (Fig.6B). Jo2 treatment alone lowered CYP2E1 protein, as did the ethanol/Jo2 compared to ethanol alone. Reasons for this are not understood, however, PNP oxidation was not altered by Jo2 alone compared saline or ethanol/Jo2 compared to ethanol alone. Immunohistochemistry confirmed that expression of CYP2E1 in situ was higher in the Eth or Eth/Jo2 group (++−+++)(Fig.6C2,6C3) compared to the Jo2 group (+) (Fig.6C1). The positive expression of CYP2E1 was mainly localized in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes in the central zone of the hepatic lobule, the area showing the highest liver toxicity by Jo2 plus ethanol treatment (Fig.1C).

Fig.6.

PNP oxidation and protein expression of CYP2E1 (A) CYP2E1 catalytic activity was measured in liver microsome fractions by evaluating the oxidation of p-nitrophenol to p-nitrocatechol in the presence of NADPH and oxygen. Results are from 6–8 mice in each group. * significantly different from the Sal group, p<0.05. # significantly different from the Jo2 group, p<0.05. (B) The levels of CYP2E1 in 20 μg of protein samples from freshly prepared microsome fractions were determined by Western blot analysis with anti-CYP2E1 polyclonal antibody. The number below the blots refer to the CYP2E1/β-actin ratio. * significantly different from the Sal or the Jo2 group, p<0.05. # significantly different from the Jo2 group, p<0.05. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for CYP2E1 was performed by using the immunoCruz ABC Kit in paraffin section with rabbit-anti-CYP2E1 antibody. Slides were visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and positive staining was reflected by the brownish yellow color in the centrilobular area. In each case, a negative control (non-immune serum) was used. (arrows, IHC×300).

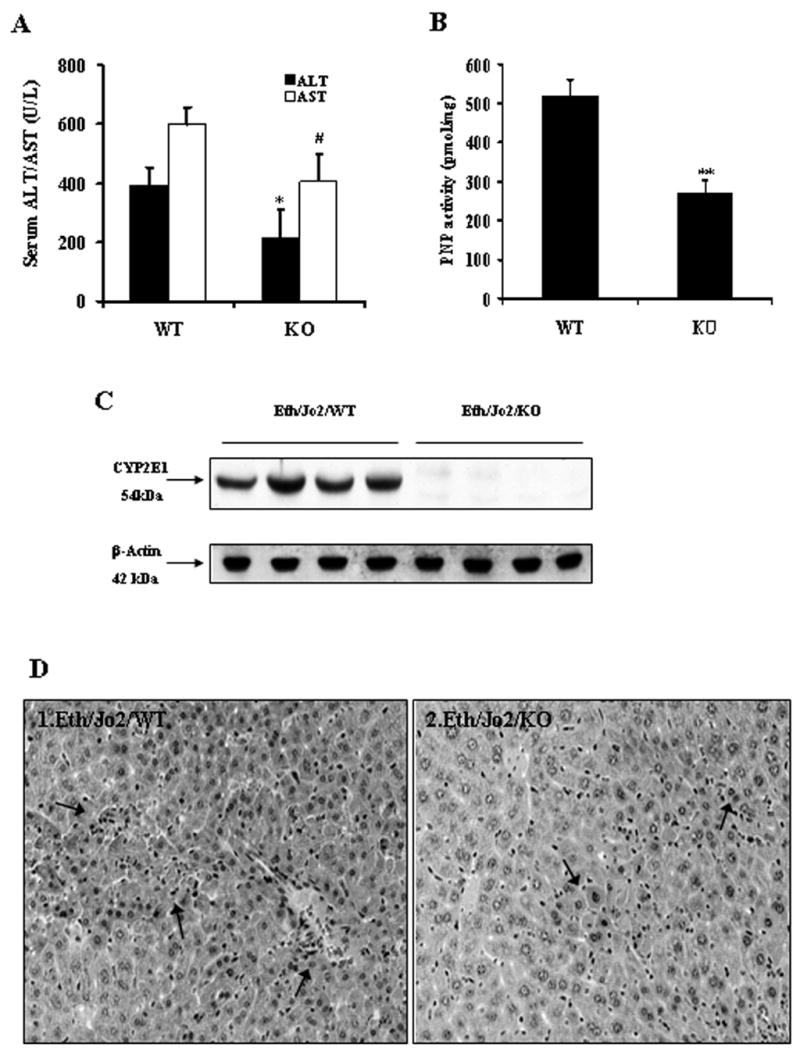

Evaluation of Hepatotoxicity in CYP2E1-Null Mice

Since CYP2E1 is elevated by the acute ethanol treatment, the potential role of CYP2E1 in the Eth/Jo2 hepatotoxicity was evaluated by using CYP2E1 KO mice. In the CYP2E1 KO mice treated with Eth/Jo2, serum ALT and AST activities were significantly lower than levels found in the 129/SV WT mice treated with Eth/Jo2 (Fig.7A). However, levels were still elevated over saline controls (ALT: 89 U/L; AST: 191 U/L). Severe pathological changes were detected in the WT treated with Eth/Jo2 in which many hepatocytes displayed extensive acidophilic necrosis in the hepatic lobule (Fig.7D1), however, there was only moderate or mild pathological changes including limited focal necrosis, acidophilic degeneration and vacuolar degeneration in the CYP2E1 KO mice treated with Eth/Jo2 (Fig.7D2). PNP hydroxylase activity was significantly lower in the KO mice treated with Eth/Jo2 compared to the WT group (Fig.7B). While CYP2E1 protein was detected in the WT mice treated with Eth/Jo2, no CYP2E1 was detected in the KO mice treated with Eth/Jo2 (Fig.7C). The lack of CYP2E1 protein in the KO suggests that the residual PNP hydroxylase activity in the KO likely is derived from other CYPS as PNP can be oxidized by several cytochrome P450s.

Fig.7.

Evaluation of CYP2E1-null mice in Eth/Jo2-induced liver damage. The CYP2E1 −/− (KO, n=10) and +/+ (WT, n=10) mice received Jo2 plus ethanol intraperitoneally as described in Materials and Methods. Serum, microsomes and liver slices were assayed for evaluation of transaminase level, CYP2E1 activity and protein level, and histopathological changes. (A) Serum ALT and AST activities in mice treated with Eth/Jo2. (B) PNP oxidation. (C) CYP2E1 protein levels. (D) Histopathological changes of liver (arrows, HE×300). * and # significantly different from the WT, p<0.05. ** significantly different from the WT, p<0.01.

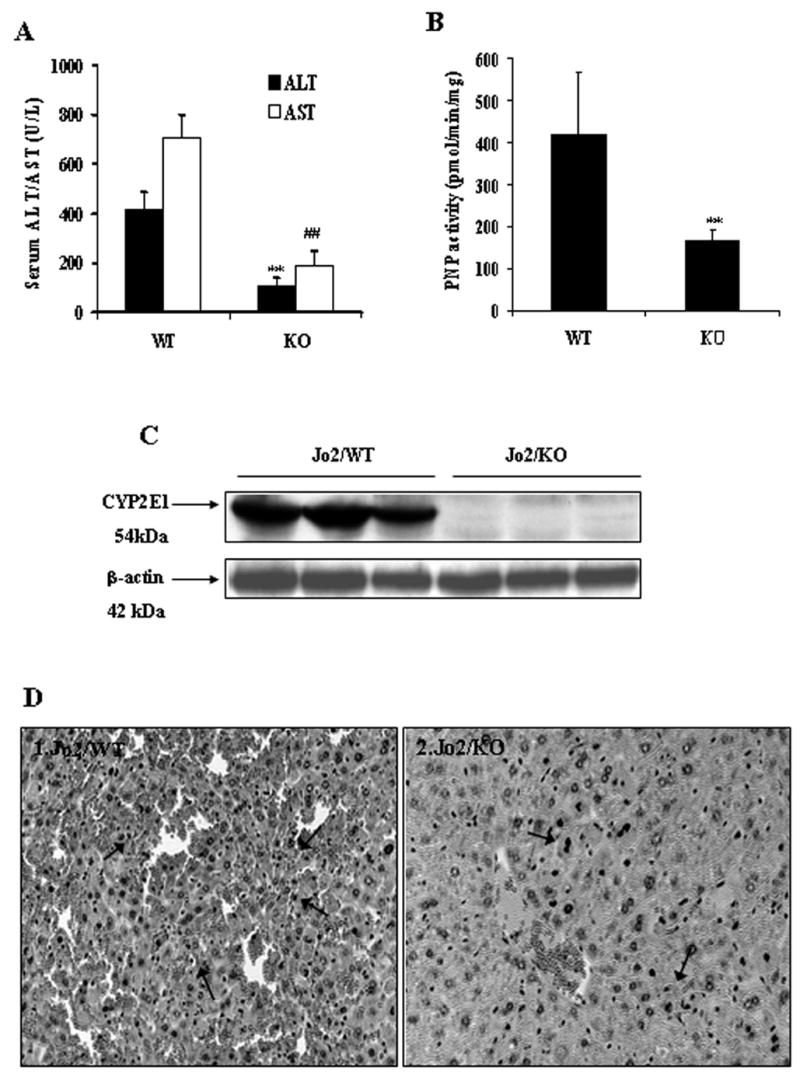

A higher concentration of Jo2 produced hepatotoxicity in the absence of ethanol pretreatment (Fig.8A). Serum ALT and AST activities were significantly lower in the CYP2E1 KO mice treated with Jo2 alone than levels found in the WT mice treated with Jo2 alone (Fig.8A). The liver was dramatically swollen and its envelop was hyperemic or hemorrhagic with dark-red color in the WT treated with Jo2 alone group, while in the KO treated with Jo2 alone, only moderate liver swelling and no abvious hemorrhage in the liver envelop was observed (data not shown). Microscopic observation showed that there were severe pathological changes in the WT treated with Jo2 alone, including extensive acidophilic necrosis in the hepatic lobule (Fig.8D1), however, there were only moderate or mild pathological changes including limited focal necrosis, acidophilic degeneration and vacuolar degeneration in the KO treated with Jo2 alone (Fig.8D2). As expected, CYP2E1 activity was significantly lower (Fig.8B) and no CYP2E1 protein was detected in the KO treated with Jo2 alone (Fig.8C).

Fig.8.

Evaluation of CYP2E1-null mice in Jo2 alone-induced liver damage. The CYP2E1 −/− (KO, n=6) and +/+ (WT, n=6) mice were treated intraperitoneally with Jo2 alone (no ethanol pretreatment), 0.5 μg/g body weight for 4 hours. Serum, microsomes and liver slices were assayed for evaluation of transaminase level, CYP2E1 activity and protein level, and histopathological changes. (A) Serum ALT and AST activities. (B) PNP oxidation . (C) CYP2E1 protein levels. (D) Histopathological changes of liver (arrows, HE×300). ** and ## significantly different from the WT plus Jo2 alone group, p<0.01.

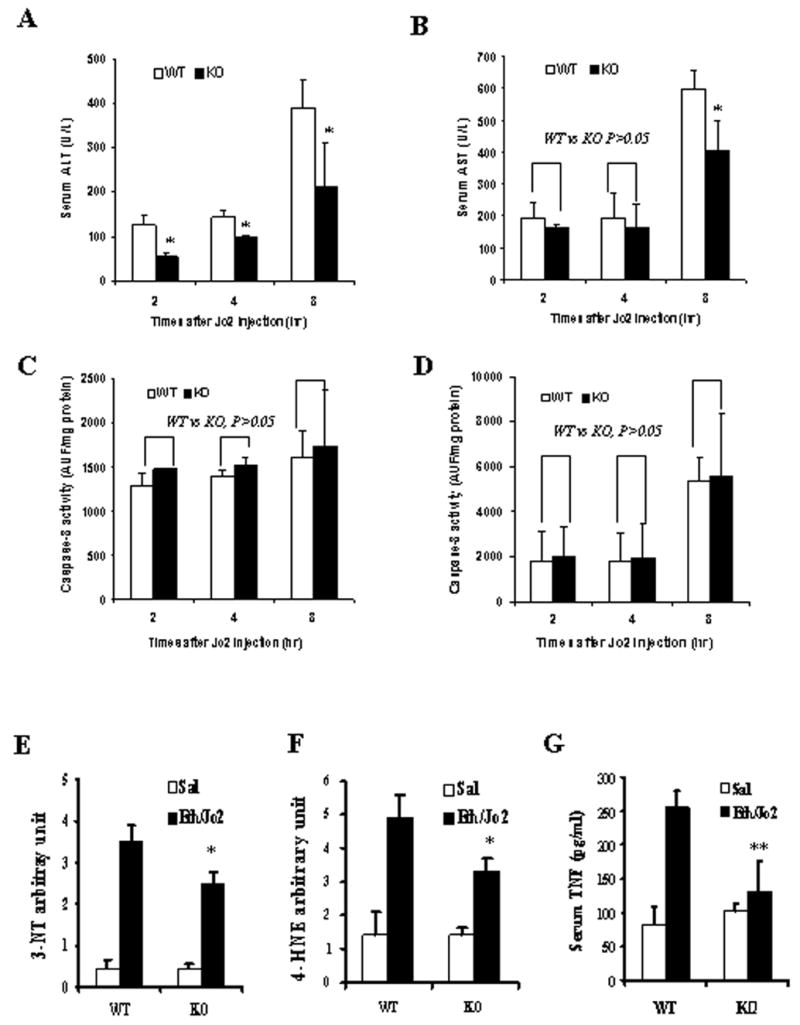

The preceding experiments were carried out on mice sacrificed 8hr after the administration of Jo2 to either saline-treated or acute ethanol-treated mice. A time course experiment with mice killed 2, 4 and 8 hr after Jo2 administration to the wild type or CYP2E1 knockout mice was carried out. In the wild type mice, ALT and AST levels were not dramatically elevated by Jo2 plus ethanol treatment (Fig.9A,9B) over saline control values (not shown) at 2 or 4 hours, but were elevated at 8 hr, the time point of the preceding experiments. Similar results were found with the CYP2E1 knockout mice as injury developed 8 hr after the administration of Jo2; the increase in ALT and AST was less than the increase found with the wild type mice (Fig.9A,9B). Caspase 8 activity was elevated 2 hr after Jo2 administration to either the wild type or the CYP2E1 knockout mice, whereas caspase 3 activity was not elevated until 8 hr after Jo2 administration with both mice models (Fig.9C,9D). However, unlike the results with respect to injury, there was no significant difference between the WT and the KO (Fig.9C,9D) with respect to increases in caspase activities. This suggests that the increase in caspase activities, unlike the increase in toxicity, is independent of CYP2E1. 3-NT and 4-HNE protein adducts were lower in the Eth/Jo2/KO group than that in the Eth/Jo2/WT group (Fig.9E,9F), but still higher than the saline controls for either group. This suggests that the increase in oxidative stress produced by the Eth/Jo2 treatment involves, in part, the induction of CYP2E1, but part of the increase is CYP2E1-independent. In the CYP2E1 KO mice treated with Eth/Jo2, serum TNF-α levels were significantly lower than that in the 129/SV WT treated with Eth/Jo2 (Fig.9G).

Fig.9.

ALT, AST, caspases activities, 3-NT and 4-HNE protein adduct levels and TNF-α content in CYP2E1-null mice following Eth/Jo2 treatment. In panels A to D, acute ethanol pretreated wild type or CYP2E1 knockout mice were killed 2, 4 or 8 hr after administration of Jo2. (A) serum ALT. (B) serum AST. (C) Caspase-8 activity in liver. (D) Caspase-3 activity in liver. In panels E to G, acute ethanol pretreated wild type or CYP2E1 knockout mice were killed 8 hr after administration of saline or Jo2. (E) 3-NT arbitrary units in liver. (F) 4-HNE arbitrary units in liver. (G) Serum TNF-α content. Assay methods of transaminase and caspase activities are as described in Materials and Methods. TNF-α content and 3-NT or 4-HNE arbitary units were assayed as below: 50 μl of liver homogenate was precoated in 96-well plates at 4°C overnight. The plates were incubated with anti-3-NT or 4-HNE antibody (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA), for 2 hrs followed by incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody and streptavidin-HRP reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) for 1 hr, respectively. The blank and BSA control were similarly assayed and the results were determined by measuring absorbance at 450 nm and 550 nm. The arbitrary units were calculated by subtracting the control values. Results are from 6–8 mice in each group. * significantly different from the WT plus Eth/Jo2 group, p<0.05. ** significantly different from the WT plus Eth/Jo2 group, p<0.01.

Disccusion

Acute ethanol can potentiate the hepatic apoptosis and necrosis by Jo2 Fas antibody treatment as shown by three fold increases of ALT or AST and more extensive degeneration, apoptotic necrosis of hepatocytes, and focal hemorrhages of the hepatic lobule in the Fas Jo2 plus acute ethanol treatment group compared to the Jo2 alone group or ethanol alone group. Only small increases of transaminases and mild changes of morphology were observed in either the Jo2 alone or ethanol alone group. Thus, the enhanced toxicity found in the Eth/Jo2 group is not merely the addition of toxicity produced by Jo2 plus the toxicity produced by ethanol. A low concentration of Jo2 was used in order to minimize toxicity and thus allow evaluation of potentiation of injury by acute ethanol pretreatment. These findings suggest that ethanol pretreatment sensitizes the liver to toxic challenge by Jo2 so as to potentiate liver damage.

The Fas/Fas-L system plays a central role in ethanol-induced hepatic apoptosis [21,23–25]. Binding of Fas to its ligand (FasL) or Fas antibody results in receptor cross-linking and apoptosis of Fas positive cells via cellular pathways including receptor oligomerization and recruitment of the Fas-associated protein with death domain, which eventually leads to the activation of caspase-8 and downstream caspases such as caspase-3 [33–38]. Liver is particularly sensitive to Fas-induced apoptosis and hepatotoxicity and the injection of Fas antibody in mice results in extensive hepatocyte necrosis and even fulminant liver failure [39]. In the current study, Fas Jo2 induced-liver injury was potentiated by acute ethanol pretreatment as development of apoptotic acidophilic necrosis in hepatocytes including focal hemorrhages and small amounts of inflammatory cell infiltration in damaged areas were observed. Injury appeared to be largely necrotic. Results from caspase activities and DNA fragmentation indicated that there were increases of caspase-8, and caspase-3 activities, and TUNEL positive cells, in the Eth/Jo2 group compared to the Jo2 alone group, suggesting apoptosis is also occurring in the Jo2 plus ethanol group. It is possible that an initial apoptotic mode of cell death may switch to a necrotic mode (or oncotic cell death) under conditions of massive toxicity or oxidative stress, as ATP which is necessary for apoptosis to proceed becomes depleted. The results from CYP2E1 knockout mice indicated that the enhanced hepatotoxicity was significantly decreased compared to the WT mice but the caspase activities were not different compared to the WT mice. This suggests that the decreased hepatotoxicity of Jo2 plus ethanol in the CYP2E1 KO mice did not involve the down-regulation of apoptotic pathways in the liver. The results also suggest that CYP2E1, unlike the liver necrosis toxicity, does not play a major role in the apoptotic toxicity induced by the Jo2 plus ethanol treatment.

Ethanol-induced oxidative stress appears to play an important role in mechanisms by which ethanol causes liver injury [40]. Induction of CYP2E1 contributes to the ethanol-induced oxidant stress. CYP2E1 levels were elevated after acute ethanol treatment as there was an increase of enzyme catalytic activity and an increase of CYP2E1 protein expression. The increase and location of the liver histopathology i.e., centrilobular zone of the liver acinus, is associated with the elevation and location of CYP2E1 in this zone. In CYP2E1 knockout mice, the enhanced hepatotoxicity by Jo2 plus ethanol was partially (but not completely) decreased compared to the CYP2E1 wild-type mice. These results suggest that one mechanism by which acute ethanol administration increases the susceptibility of the liver to hepatotoxicity by Fas Jo2 antibody is due to increases in the expression of CYP2E1 by the ethanol pretreatment. CYP2E1 may promote Jo2 toxicity even in the absence of acute ethanol pretreatment. When higher concentrations of Jo2 alone were administered, hepatic toxicity was produced in the WT mice, however, injury was considerably reduced in the Jo2-treated CYP2E1 KO mice. Thus, even basal non-induced levels of CYP2E1 appear to play a role in potentiating Jo2 toxicity. Formation of peroxynitrite anion and nitrotyrosine adducts would result from interaction between superoxide anion and NO. Increases in superoxide production would occur as a result of induction of CYP2E1 while increases in NO occur when iNOS is induced.

Alcohol-induced liver injury is associated with enhanced lipid peroxidation, protein carbonyl formation, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and decreases in hepatic antioxidant defense especially GSH [41–43]. Mitochondrial MDA, protein carbonyl formation, 3-NT adducts, iNOS and 4-HNE adducts were higher in the Jo2 plus ethanol group compared to the Jo2 alone or ethanol alone group. GSH was lower in all the treated groups and lowest levels were in the the Jo2 plus ethanol group. These results suggest that the enhanced hepatotoxicity might come from an increase of oxidative and nitrosative stress and perhaps decrease of antioxidant defense in the liver of mice treated with Jo2 plus ethanol. TNF-α levels were also elevated in the Jo2 plus ethanol treated group compared to the saline controls, which may also contribute to an increase in oxidative stress. TNF-α levels were decreased in the CYP2E1 KO mice treated with Eth/Jo2 compared to the WT, which may play a role in the lowering of the hepatic injury. Future experiments with TNF-α receptor knockout mice and neutralizing TNF-α antibodies are planned to further evaluate a role for TNF-α in the potentiation of Jo2 toxicity by acute ethanol pretreatment. In order to evaluate whether oxidative or nitrosative stress contribute to or are merely associated with the enhanced hepatotoxicity by Jo2 plus ethanol pretreatment, an antioxidant (NAC) or an inhibitor of iNOS or cytokine (TNF-α) production (GdCl3, PTX) were administrated prior to the Jo2 treatment. There was at least a partial decrease of hepatotoxicity after using GdCl3, 1400W and NAC, respectively, consistent with the idea that the increase of Jo2 plus ethanol hepatotoxicity involves oxidative stress (protection by NAC), nitrosative stress (protection by 1400W) and TNF-α/inflammatory reactions (protection by GdCl3). PTX was recently shown to prevent the increase in plasma TNF-α, triglycerides and caspase-3 activity when alcohol was administrated by gastric intubation to obese mice [44]. PTX was slightly but not significantly protective against the Jo2 plus ethanol toxicity. GdCl3 pretreatment in mice to inactivate Kupffer cells resulted in a significantly decrease of plasma ALT after endotoxin administration [45]. GdCl3 also blocked alcohol toxicity in rats treated chronically with intragastric alcohol [46]. 1400W, a selective iNOS inhibitor, markedly reduced the increased plasma NO levels after administration in endotoxin-injected mice [47] and decreased alcohol liver toxicity in mice fed ethanol intragastrically by inhibiting iNOS in the Kupffer cells [48]. NAC was shown to decrease ethanol hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats fed ethanol via total enteral nutrition [49].

As mentioned above, the Jo2 plus ethanol toxicity was lower in CYP2E1 knockout mice as compared to WT-treated mice. However, significant toxicity by Jo2 plus ethanol persisted in the CYP2E1 null mice. This decrease of hepatotoxicity is associated with a decrease of oxidation protein adducts such as 3-NT and 4-HNE as well as TNF-α levels in the CYP2E1 knockout mice, but again significant increases in 3-NT and 4-HNE protein adducts persisted in the Jo2 plus ethanol CYP2E1 knockout mice compared to saline-treated wild type or CYP2E1 knockout mice. This suggests that the enhanced oxidative and nitrosative stress is derived, in part, from CYP2E1-derived ROS and lipid peroxidation, but also by CYP2E1-independent pathways. The latter may reflect Jo2-derived ROS and NO, or cytokine-derived ROS. Alternatively, other CYPs may be induced in the CYP2E1 knockout mice e.g. CYP4A10 and CYP4A14 were elevated in CYP2E1 knockout mice fed a methionine choline deficient diet [50]. To evaluate a potential role for other CYPS, we treated the CYP2E1-knockouts with aminobenzotriazole (ABT), which is known to decrease total P450 levels [51,52,53]. Total P450 levels were lowered about 62% after treatment of CYP2E1 knockout mice with 100 mg/kg ABT (once a day for 3 days). The residual liver injury in the CYP2E1 knockout mice was lowered about 32% by the ABT treatment, indeed suggesting a role for other CYPS in the Jo2 plus ethanol toxicity. Some injury still remained compared to the saline controls which suggests non-P450 dependent mechanisms. Further studies are needed to define these non-P450 dependent pathways. We believe that ethanol pretreatment potentiates Jo2-induced hepatic toxicity by elevating CYP2E1-dependent and CYP2E1-independent pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS Grant AA-03312 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. We thank Dr. Frank J. Gonzalez for providing CYP2E1 Knockout mice to this study.

Abbreviations

- ABT

aminobenzotriazole

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CYP2E1

cytochrome P450 2e1

- DNPH

2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GdCl3

gadolinium chloride

- HE

hematoxylin-eosin

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrosine

- PNP

p-nitrophenol

- PTX

pentoxifylline

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

- 1400W

N-[(3-aminomethyl) benzyl] acetamidine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tsukamoto H, Lu SC. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver injury. FASEB J. 2001;15:1335–1349. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0650rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoek JB, Pastorino JG. Cellular signaling mechanisms in alcohol-induced liver damage. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2004;24:257–272. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouach H, Fataccioli V, Gentil M, French SW, Morimoto M, Nordmann R. Effect of chronic ethanol feeding on lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in relation to liver pathology. Hepatology. 1997;25:351–355. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French SW, Wong K, Jui L, Albano E, Hagbjork AL, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Effect of ethanol on cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), lipid peroxidation, and serum protein adduct formation in relation to liver pathology pathogenesis. Exp Mol Pathol. 1993;58:61–75. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polavarapu R, Spitz DR, Sim JE, Follansbee MH, Oberley LW, Rahemtulla A, Nanji AA. Increased lipid peroxidation and impaired antioxidant enzyme function is associated with pathological liver injury in experimental alcoholic liver disease in rats fed diets high in corn oil and fish oil. Hepatology. 1998;27:1317–1323. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guengerich FP, Kim DH, Iwasaki M. Role of human cytochrome P-450 IIE1 in the oxidation of many low molecular weight cancer suspects. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;4:168–179. doi: 10.1021/tx00020a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang CS, Yoo JS, Ishizaki H, Hong JY. Cytochrome P450IIE1: roles in nitrosamine metabolism and mechanisms of regulation. Drug Metab Rev. 1990;22:147–159. doi: 10.3109/03602539009041082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koop DR. Oxidative and reductive metabolism by cytochrome P450 2E1. FASEB J. 1992;6:724–730. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1537462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dianzani MU. Lipid peroxidation in ethanol poisoning: a critical reconsideration. Alcohol Alcohol. 1985;20:161–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cederbaum AI. Microsomal generation of reactive oxygen species and their possible role in alcohol hepatotoxicity. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1991;1:291–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bondy SC. Ethanol toxicity and oxidative stress. Toxicol Lett. 1992;63:231–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(92)90086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsukamoto H, Horne W, Kamimura S, Niemela O, Parkkila S, Yla-Herttuala SBrittenham GM. Experimental liver cirrhosis induced by alcohol and iron. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:620–630. doi: 10.1172/JCI118077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morimoto M, Zern MA, Hagbjork AL, Ingelman-Sundberg M, French SW. Fish oil, alcohol, and liver pathology: role of cytochrome P450 2E1. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;207:197–205. doi: 10.3181/00379727-207-43807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nanji AA, Zhao S, Sadrzadeh SM, Dannenberg AJ, Tahan SR, Waxman DJ. Markedly enhanced cytochrome P450 2E1 induction and lipid peroxidation is associated with severe liver injury in fish oil-ethanol-fed rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1280–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castillo T, Koop DR, Kamimura S, Triadafilopoulos G, Tsukamoto H. Role of cytochrome P-450 2E1 in ethanol-, carbon tetrachloride- and iron-dependent microsomal lipid peroxidation. Hepatology. 1992;16:992–996. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French SW, Morimoto M, Reitz RC, Koop D, Klopfenstein B, Estes K, Clot P, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Albano E. Lipid peroxidation, CYP2E1 and arachidonic acid metabolism in alcoholic liver disease in rats. J Nutr. 1997;127:907S–911S. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.907S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gouillon Z, Lucas D, Li J, Hagbjork AL, French BA, Fu P, Fang C, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Donohue TM, Jr, French SW. Inhibition of ethanol-induced liver disease in the intragastric feeding rat model by chlormethiazole. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;224:302–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benedetti A, Brunelli E, Risicato R, Cilluffo T, Jezequel AM, Orlandi F. Subcellular changes and apoptosis induced by ethanol in rat liver. J Hepatol. 1988;6:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(88)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldin RD, Hunt NC, Clark J, Wickramasinghe SN. Apoptotic bodies in a murine model of alcoholic liver disease: reversibility of ethanol-induced changes. J Pathol. 1993;171:73–76. doi: 10.1002/path.1711710115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neuman MG, Brenner DA, Rehermann B, Taieb J, Chollet-Martin S, Cohard M, Garaud JJ, Poynard T, Katz GG, Cameron RG, Shear NH, Gao B, Takamatsu M, Yamauchi M, Ohata M, Saito S, Maeyama S, Uchikoshi T, Toda G, Kumagi T, Akbar SM, Abe M, Michitaka K, Horiike N, Onji M. Mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease: cytokines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:251S–253S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galle PR, Hofmann WJ, Walczak H, Schaller H, Otto G, Stremmel W, Krammer PH, Runkel L. Involvement of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor and ligand in liver damage. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1223–1230. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurose I, Higuchi H, Miura S, Saito H, Watanabe N, Hokari R, Hirokawa M, Takaishi M, Zeki S, Nakamura T, Ebinuma H, Kato S, Ishii H. Oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis of hepatocytes exposed to acute ethanol intoxication. Hepatology. 1997;25:368–378. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v25.pm0009021949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z, Sun X, Kang YJ. Ethanol-induced apoptosis in mouse liver: Fas- and cytochrome c-mediated caspase-3 activation pathway. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:329–338. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61699-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minana JB, Gomez-Cambronero L, Lloret A, Pallardo FV, Del Olmo J, Escudero A, Rodrigo JM, Pellíin A, Viña JR, Viña J, Sastre J. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and CD95 ligand: a dual mechanism for hepatocyte apoptosis in chronic alcoholism. Hepatology. 2002;35:1205–1214. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sosa L, Vidlak D, Strachota JM, Pavlik J, Jerrells TR. Rescue of in vivo FAS-induced apoptosis of hepatocytes by corticosteroids either associated with alcohol consumption by mice or provided exogenously. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaciuc IV, Fortunato F, D'Souza NB, Hill DB, Schmidt J, Lee EY, McClain CJ. Modulation of caspase-3 activity and Fas ligand mRNA expression in rat liver cells in vivo by alcohol and lipopolysaccharide. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castaneda F, Kinne RK. Apoptosis induced in HepG2 cells by short exposure to millimolar concentrations of ethanol involves the Fas-receptor pathway. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2001;127:418–424. doi: 10.1007/s004320000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama N, Eichhorst ST, Muller M, Krammer PH. Ethanol-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells proceeds via intracellular Ca(2+) elevation, activation of TLCK-sensitive proteases, and cytochrome c release. Exp Cell Res. 2001;269:202–213. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guy CS, Wang J, Michalak TI. Hepatocytes as cytotoxic effector cells can induce cell death by CD95 ligand-mediated pathway. Hepatology. 2006;43:1231–1240. doi: 10.1002/hep.21201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Lu Y, Cederbaum AI. Induction of cytochrome P450 2E1 increases hepatotoxicity caused by Fas agonistic Jo2 antibody in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:400–410. doi: 10.1002/hep.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinke LA, Moyer MJ. P-Nitrophenol hydroxylation. A microsomal oxidation which is highly inducible by ethanol. Drug Metab Dispos. 1985;13:548–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esterbauer H, Cheeseman KH. Determination of aldehydic lipid peroxidation products: malonaldehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:407–421. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86134-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Claiborne A, Fridovich I. Purification of the o-dianisidine peroxidase from Escherichia coli B. Physicochemical characterization and analysis of its dual catalatic and peroxidatic activities. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4245–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okamoto S, Yokohama S, Yoneda M, Haneda M, Nakamura K. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha plays a crucial role in concanavalin A-induced liver injury through induction of proinflammatory cytokines in mice. Hepatol Res. 2005;32:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy JA, Lewis H, Clements WD, Kirk SJ, Campbell G, Halliday MI, Rowlands BJ. Kupffer cell blockade, tumour necrosis factor secretion and survival following endotoxin challenge in experimental biliary obstruction. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1410–1414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen D, McKallip RJ, Zeytun A, Do Y, Lombard C, Robertson JL, Mak TW, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. CD44-deficient mice exhibit enhanced hepatitis after concanavalin A injection: evidence for involvement of CD44 in activation-induced cell death. J Immunol. 2001;166:5889–5897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.5889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tagawa Y, Kakuta S, Iwakura Y. Involvement of Fas/Fas ligand system-mediated apoptosis in the development of concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4105–4113. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4105::AID-IMMU4105>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Higuchi H, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Diet associated hepatic steatosis sensitizes to Fas mediated liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2003;39:978–983. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, Matsuzawa A, Kasugai T, Kitamura Y, Itoh N, Suda T. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364:806–809. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dey A, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol and oxidative liver injury. Hepatology. 2006;43:S63–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knecht KT, Adachi Y, Bradford BU, Iimuro Y, Kadiiska M, Xuang QH, Thurman RG. Free radical adducts in the bile of rats treated chronically with intragastric alcohol: inhibition by destruction of Kupffer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arteel GE. Oxidants and antioxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:778–790. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iimuro Y, Bradford BU, Yamashina S, Rusyn I, Nakagami M, Enomoto N, Kono H, Frey W, Forman D, Brenner D, Thurman RG. The glutathione precursor L-2-oxothiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid protects against liver injury due to chronic enteral ethanol exposure in the rat. Hepatology. 2000;31:391–398. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robin MA, Demeilliers C, Sutton A, Paradis V, Maisonneuve C, Dubois S, Poirel O, Letteron P, Pessayre D, Fromenty B. Alcohol increases tumor necrosis factor alpha and decreases nuclear factor-kappa to activate hepatic apoptosis in genetically obese mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:1280–1290. doi: 10.1002/hep.20949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Q, Kim J, Sharma RP. Fumonisin B1 hepatotoxicity in mice is attenuated by depletion of Kupffer cells by gadolinium chloride. Toxicology. 2005;207:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koop DR, Klopfenstein B, Iimuro Y, Thurman RG. Gadolinium chloride blocks alcohol-dependent liver toxicity in rats treated chronically with intragastric alcohol despite the induction of CYP2E1. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:944–950. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.6.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakaguchi Y, Shirahase H, Ichikawa A, Kanda M, Nozaki Y, Uehara Y. Effects of selective iNOS inhibition on type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Life Sci. 2004;75:2257–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKim SE, Gabele E, Isayama F, Lambert JC, Tucker LM, Wheeler MD, Connor HD, Mason RP, Doll MA, Hein DW, Arteel GE. Inducible nitric oxide synthase is required in alcohol-induced liver injury: studies with knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1834–1844. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ronis MJ, Butura A, Sampey BP, Shankar K, Prior RL, Korourian S, Albano E, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Petersen DR, Badger TM. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats fed via total enteral nutrition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leclercq IA, Farrell GC, Field J, Bell DR, Gonzalez FJ, Robertson GR. CYP2E1 and CYP4A as microsomal catalysts of lipid peroxides in murine nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1067–1075. doi: 10.1172/JCI8814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isayama F, Froh M, Bradford BU, McKim SE, Kadiiska MB, Connor HD, Mason RP, Koop DR, Wheeler MD, Arteel GE. The CYP inhibitor 1-aminobenzotriazole does not prevent oxidative stress associated with alcohol-induced liver injury in rats and mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:1568–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradford BU, Kono H, Isayama F, Kosyk O, Wheeler MD, Akiyama TE, Bleye L, Krausz KW, Gonzalez FJ, Koop DR, Rusyn I. Cytochrome P450 CYP2E1, but not nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, is required for ethanol-induced oxidative DNA damage in rodent liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:336–344. doi: 10.1002/hep.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adler ID, Baumgartner A, Gonda H, Friedman MA, Skerhut M. 1-Aminobenzotriazole inhibits acrylamide-induced dominant lethal effects in spermatids of male mice. Mutagenesis. 2000;15:133–136. doi: 10.1093/mutage/15.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]