Abstract

Cuticular waxes play a pivotal role in limiting transpirational water loss across the primary plant surface. The astomatous fruits of the tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) ‘MicroTom’ and its lecer6 mutant, defective in a β-ketoacyl-coenzyme A synthase, which is involved in very-long-chain fatty acid elongation, were analyzed with respect to cuticular wax load and composition. The developmental course of fruit ripening was followed. Both the ‘MicroTom’ wild type and lecer6 mutant showed similar patterns of quantitative wax accumulation, although exhibiting considerably different water permeances. With the exception of immature green fruits, the lecer6 mutant exhibited about 3- to 8-fold increased water loss per unit time and fruit surface area when compared to the wild type. This was not the case with immature green fruits. The differences in final cuticular barrier properties of tomato fruits in both lines were fully developed already in the mature green to early breaker stage of fruit development. When the qualitative chemical composition of fruit cuticular waxes during fruit ripening was investigated, the deficiency in a β-ketoacyl-coenzyme A synthase in the lecer6 mutant became discernible in the stage of mature green fruits mainly by a distinct decrease in the proportion of n-alkanes of chain lengths > C28 and a concomitant increase in cyclic triterpenoids. This shift in cuticular wax biosynthesis of the lecer6 mutant appears to be responsible for the simultaneously occurring increase of water permeance. Changes in cutin composition were also investigated as a function of developmental stage. This integrative functional approach demonstrates a direct relationship between cuticular transpiration barrier properties and distinct chemical modifications in cuticular wax composition during the course of tomato fruit development.

One of the major functions of the plant cuticle is to limit transpirational water loss from the primary plant surface (Riederer and Schreiber, 2001; Burghardt and Riederer, 2006). Other functions include protection against pathogens, herbivores, UV radiation, and mechanical damage (Gniwotta et al., 2005; Kerstiens, 1996a, 1996b; Heredia, 2003). The cuticular membrane is composed of a polymer matrix (cutin) and associated solvent-soluble lipids (cuticular waxes), which can be divided into two spatially distinct layers: epicuticular waxes coating the surface and intracuticular waxes embedded in the cutin matrix. It is known from Prunus laurocerasus (Jetter et al., 2000) and tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum; Vogg et al., 2004) fruit that epi- and intracuticular wax layers exhibit significant qualitative differences. Wax composition varies in a species-, organ-, and tissue-specific manner and commonly consists of homologous series of very-long-chain aliphatic molecules (e.g. alkanoic acids, alkanols, aldehydes, alkanes, esters) and of cyclic compounds (e.g. triterpenoids and phenylpropanoids; for review, see von Wettstein-Knowles, 1993; Post-Beittenmiller, 1996; Kunst and Samuels, 2003; Jetter et al., 2006).

Because the permeability of the cuticle is not necessarily correlated with its thickness or wax coverage, its interfacial properties more likely are determined by the chemical composition and/or the spatial arrangement/assembly of its components (Riederer and Schreiber, 1995, 2001; Kerstiens, 2006). Although cuticular membranes are mainly considered as a lipid barrier, hydrophilic structures like nonesterified hydroxyl and carboxyl groups within the cutin polymer (Schönherr and Huber, 1977) and polysaccharides like pectin and cellulose (Jeffree, 1996) are also present. Currently, two parallel and independent pathways for diffusion across the plant cuticle are discussed: (1) a lipophilic pathway accessible for nonionic lipophilic molecules composed of lipophilic cutin and wax domains; and (2) a polar pathway open to inorganic ions and small uncharged and charged organic molecules, which is postulated to consist of a continuum of polar materials across the cuticle (Popp et al., 2005; Schönherr, 2006; Schreiber, 2006). There is evidence that water as a small uncharged polar molecule may have access to both pathways of transport (Schönherr and Merida, 1981; Niederl et al., 1998; Riederer and Schreiber, 2001; Schlegel et al., 2005; Riederer, 2006).

Several wax mutants are known from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and other plants. They have been analyzed for modifications in cuticular wax composition. Until recently, the differences in wax composition that could be traced down to the molecular level were discernible for only for a limited number of mutants (Chen et al., 2003; Kunst and Samuels, 2003; Pighin et al., 2004; Goodwin et al., 2005; Sturaro et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2006; Nawrath, 2006; Rowland et al., 2006). Hence, our knowledge on the components of wax biosynthesis is still fairly restricted, most notably because the precise functions of many of the as yet identified genes involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis still remain to be determined.

Another obstacle that has to be overcome is the difficulty in correlating the mutant phenotypes with functional aspects (Kerstiens et al., 2006). Particularly with regard to water loss, Arabidopsis, with its comparably small and delicate organs, is not suitable for the functional analysis of the intact plant cuticle. As described by Kerstiens (1996b), residual stomatal transpiration even under conditions of minimal stomatal conductance cannot be excluded. Therefore, analysis of astomatous plant surfaces is favorable. Fruits of the dwarf tomato ‘MicroTom’, a recognized model cultivar for tomato functional genomics (Meissner et al., 1997, 2000; Emmanuel and Levy, 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2005), turned out to ideally serve this purpose (Vogg et al., 2004). A recent series of publications underlined the essential requirement for a suitable model system to relate wax composition to cuticular permeability (Kerstiens, 2006; Kerstiens et al., 2006).

The chemical composition of tomato fruit cuticular wax, which predominantly consists of very-long-chain alkanes and triterpenoids, has been the topic of previous investigations (Hunt and Baker, 1980; Baker et al., 1982; Bauer et al., 2004a, 2004b). Lecer6, a defined Activation (Ac)/Dissociation (Ds) transposon-tagged tomato wax mutant deficient in a β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase, an essential element of a very-long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA) elongase complex, was shown to be impaired in fruit cuticular water barrier properties as described in a previous publication. In contrast to the wild type, cuticles of fully ripened lecer6 fruits were devoid of n-alkanes with chain lengths beyond C31, whereas shorter chains and branched hydrocarbons remained unaffected. Mutant fruit wax showed a distinctly increased portion of intracuticular triterpenoids, a reduction of intracuticular aliphatics, and significantly elevated water permeability (Vogg et al., 2004).

Quantitative composition of a cuticle depends on several factors, like genetics, climate, type of tissue, and developmental stage (Dixon et al., 1997; Gordon et al., 1998; Jetter and Schäffer, 2001; Hooker et al., 2002; Cameron et al., 2006; Shepherd and Griffiths, 2006). The data on tomato fruit wax development presently available (Haas, 1974; Baker et al., 1982; Bauer et al., 2004b) are restricted to mature fruits or reflect developmental changes in reference to fruit size only. By analyzing seven different stages of fruit ripening according to fruit size and color (categories I–VII; Fig. 1) under optimized extraction conditions and in more detail, this study aims at broadening our knowledge of the developmental pattern of tomato fruit wax component accumulation in combination with functional analyses of cuticular water permeance properties, while focusing on the effects caused by the specific β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase deficiency in the lecer6 mutant.

Figure 1.

Assignment of representative ‘MicroTom’ wild-type (A) and ‘MicroTom’ LeCER6-deficient (B) fruits to the ripening categories. Fruits were arranged into seven groups according to size and color: I, immature green; II, mature green; III, early breaker; IV, breaker; V, orange; VI, red ripe; and VII, red overripe. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

RESULTS

Cuticular Water Permeability during Maturation of Tomato Wild-Type and LeCER6-Deficient Fruits

‘MicroTom’ wild-type fruits assigned to fruit-ripening category I (immature green) exhibited virtually the same cuticular water permeance as the LeCER6-deficient fruits of the same developmental stage (Table I). In category II, representing mature green fruits, lecer6 fruits had significantly higher permeance values (2.8-fold) when compared to the wild type. Following the transition from category I to category II, wild-type fruits showed a decrease in cuticular water permeance of about 96%, whereas mutant fruits exhibited a reduction of permeance values by about 89%. In categories III and IV, covering early breaker and breaker fruit developmental stages, water permeance was further reduced by another 2% of the initial value for ‘MicroTom’ wild-type fruits, but no more for the lecer6 mutant. Orange to red overripe fruits, assigned to categories V to VII, exhibited only minor changes concerning cuticular water permeance in the further course of fruit maturation. The water permeance of wild-type fruits finally decreased to 2% of the category I value, whereas the permeance of lecer6 fruits was reduced to only 16% of the initial value in category I. Hence, in categories III to VII, lecer6 mutant fruits exhibited an 8-fold increased water loss per unit time and fruit surface area when compared to the wild type.

Table I.

Permeance for water (×10−5 m s−1) of ‘MicroTom’ wild-type and ‘MicroTom’ LeCER6-deficient fruits of seven developmental categories of untreated, gum arabic-stripped, chloroform-extracted, and peeled tomato fruits

Within each line, treatments were compared with a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and subsequent multiple comparison of ranks; significant differences are marked with different letters (P < 0.05). The ratio between ‘MicroTom’ lecer6 and ‘MicroTom’ wild type was tested with the Mann-Whitney U-test. n.s., Not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are shown as means ± sd (n = 10).

| Category | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | Wild type | 46.0 ± 15.7A | 1.8 ± 0.3B | 0.9 ± 0.2B | 1.1 ± 0.2B | 1.1 ± 0.3B | 0.9 ± 0.2B | 0.9 ± 0.2B |

| lecer6 | 47.5 ± 25.4a | 5.1 ± 1.6a | 7.9 ± 2.3a | 9.0 ± 2.8a | 9.0 ± 4.4a | 7.2 ± 1.6a | 7.8 ± 1.6a | |

| Ratio | 1.0n.s. | 2.8*** | 8.4*** | 8.1*** | 8.2*** | 8.2*** | 8.5*** | |

| Gum arabic | Wild type | 96.5 ± 26.4A | 6.7 ± 2.7B | 2.2 ± 0.6B | 3.3 ± 1.1B | 2.5 ± 0.5B | 3.0 ± 0.9B | 3.5 ± 0.8B |

| lecer6 | 76.9 ± 28.9a | 21.6 ± 8.5a | 19.1 ± 4.6a | 17.4 ± 5.8a | 16.2 ± 5.7a | 13.5 ± 4.5a | 11.7 ± 2.9a | |

| Ratio | 0.8n.s. | 3.2*** | 8.5*** | 5.2*** | 6.6*** | 4.5*** | 3.4*** | |

| Chloroform | Wild type | 232.2 ± 93.8A | 79.3 ± 8.3AB | 65.0 ± 6.4ABC | 51.2 ± 6.7BC | 45.3 ± 13.6BC | 27.6 ± 7.0C | 24.4 ± 3.9C |

| lecer6 | 224.2 ± 77.2a | 111.4 ± 10.1a | 90.8 ± 12.3ab | 75.9 ± 8.0abc | 68.6 ± 11.2abc | 48.6 ± 7.9bc | 53.8 ± 9.0b | |

| Ratio | 1.0n.s. | 1.4*** | 1.4*** | 1.5*** | 1.5*** | 1.8*** | 2.2*** | |

| Peeled | Wild type | – | 133.8 ± 17.0A | 141.3 ± 22.3A | 138.8 ± 37.9A | 129.5 ± 17.4A | 132.3 ± 14.5A | 159.2 ± 47.5A |

| lecer6 | – | 173.9 ± 15.5a | 217.4 ± 17.0a | 213.8 ± 38.1a | 182.7 ± 33.1a | 184.9 ± 16.2a | 203.6 ± 34.2a | |

| Ratio | – | 1.3*** | 1.5*** | 1.5*** | 1.4*** | 1.4** | 1.3*** |

Data on permeance for water within categories II to VII differed significantly between both lines.

Effects of Wax Extraction and Different Removal Techniques

To analyze the individual effects of epi- and intracuticular wax on water permeance, chloroform extraction of total cuticular waxes and mechanical fractionation of epi- and intracuticular waxes was applied using ‘MicroTom’ wild-type and ‘MicroTom’ lecer6 fruits of all selected developmental categories I to VII (Table I). The relevance of the outermost epicuticular waxes on cuticular water permeance was analyzed after selective removal of this wax layer with gum arabic, a solvent-free water-based polar organic adhesive. Gum arabic treatment resulted in a 2- to 4-fold increase of water permeance for both wild-type and lecer6 mutant fruits. As with untreated fruits, significant differences between wild type and lecer6 became discernible in category II. Hence, mechanical removal of the epicuticular waxes with gum arabic did not abolish initially measured differences in permeance between wild type and lecer6. In later stages of fruit development (categories IV–VII) the differences between wild-type and lecer6 permeances were slightly decreased. In category II, gum arabic treatment of lecer6 fruits resulted in a 4-fold increase of permeance values, whereas fruits of category VII showed only 1.5-fold elevated permeances in comparison to untreated mutant fruits. In line with this, lecer6 fruits exhibited slightly decreasing permeance values during the course of fruit ripening (categories III–VII), whereas wild-type values remained more or less constant in the respective developmental stages.

Chloroform dipping, however, increased permeances in fruits of category I by a factor of 5. This effect was distinctly enhanced with fruits of category II showing a 44-fold increase of permeance for the wild type and a 22-fold increase for lecer6 compared to the respective values of untreated fruits. After chloroform dipping, both wild-type and lecer6 fruits exhibited a distinct decrease of permeance values during the course of fruit ripening. However, this decrease was more pronounced with wild-type than with lecer6 fruits.

Even the complete removal of the fruit cuticle resulted in distinct permeance values of wild-type and lecer6 fruits. Peeled lecer6 fruits continuously exhibited 1.3- to 1.5-fold elevated permeance values when compared to wild-type fruits of the respective developmental categories II to VII. Nevertheless, a distinct decrease of permeance values in the course of fruit development was no longer observed with fruits fully devoid of their cuticular transpiration barrier.

According to a simplifying model proposed by Schönherr (1976), epicuticular waxes (ECW) and intracuticular waxes (ICW) and the dewaxed cutin matrix (DCM) can be considered to act, in analogy to electrical circuits, as diffusion resistances in series. Resistances are the reciprocal of water permeances. Therefore, the relative contribution of wax layers to total resistance may be estimated from the equation rCM = rWAX + rDCM = rECW + rICW + rDCM, where rCM, rWAX, and rDCM correspond to the resistances of the cuticular membrane (CM), the wax layers (ECW, ICW), and DCM, respectively (Knoche et al., 2000). By applying this model to our data (Fig. 2), the distinctly increasing diffusion resistances during the first three categories of fruit ripening became evident in untreated wild-type fruits (rCM), whereas lecer6 fruits exhibited a significant increase only during the transition from category I to II. For wild-type fruits, gum arabic stripping exerted a particularly pronounced effect on cuticular resistance, resulting in a significant decrease. Resistances largely followed the pattern observed for untreated fruits in the time course of ripening. Chloroform dipping further reduced cuticular resistance paralleled by a continuous increase of resistance over the seven categories of fruit ripening in wild type and lecer6 mutant.

Figure 2.

Cuticular resistances of tomato wild-type (A) and LeCER6-deficient (B) ‘MicroTom’ fruit cuticles of different developmental categories against water loss. Resistances were calculated as the reciprocals of water permeances of untreated, gum arabic-stripped, and chloroform-extracted tomato fruits. Data are shown as means ± sd (n = 10).

Cuticular Wax Coverage and Compound Classes

‘MicroTom’ fruit cuticular waxes, derived from chloroform extracts, mainly consisted of n-alkanes, pentacyclic triterpenoids, sterol derivatives, primary alkanols, and alkanoic acids. This composition was analyzed over categories I to VII during fruit development both in the wild type and lecer6 mutant. Immature green fruits (category I) of the wild type and lecer6 mutant did not exhibit major differences regarding total cuticular wax compound class composition (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, in category I, wild-type fruits (3.98 ± 0.88 μg cm−2) possessed an almost 2-fold higher overall wax load as compared to lecer6 mutant fruits (2.33 ± 0.37 μg cm−2; Student's t test P = 0.01, t = 3.8). In category II, both lines had accumulated a similar amount of cuticular waxes (wild type, 8.06 ± 1.36 μg cm−2; lecer6, 10.02 ± 1.66 μg cm−2; P = 0.03, t = 2.6). Therefore, the increase of wax accumulation between categories I and II was most striking for lecer6 mutant fruits. Moreover, in category II, significant differences in wax composition between mutant and wild type became apparent, which, in particular, concerned the deposition of aliphatics, especially n-alkanes (P < 0.001, t = 15.3) and cyclic compounds, like triterpenoids and sterol derivatives (P < 0.001, t = 5.6). When compared to wild-type fruit wax composition, LeCER6-deficient fruits exhibited a sharp decrease in the proportion of aliphatic compounds, which was paralleled by distinct accumulation of triterpenoids. Peaking in category II, the proportion of triterpenoids in wild-type wax (approximately 53% of total wax) exhibited a continuous relative decline following the time course of further fruit ripening (category VII, approximately 21% of total wax), whereas it remained more or less constant in lecer6 mutant fruits grouped into categories II to VII (approximately 80% of total wax). The relative proportion of the n-alkanes, another major component class present in wild-type wax, was 45% in the total cuticular wax of category I fruits, decreased in category II to approximately 33%, and finally contributed 55% to the total wax composition in category VII.

Figure 3.

Total cuticular wax quantities and relative wax compositions of wild-type (A) and LeCER6-deficient (B) tomato fruits of seven different developmental categories. Wax quantities of different categories within each line were compared by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference mean-separation test for unequal n; significant differences are marked with different letters (P < 0.05). Data are shown as means ± sd (n = 3–6).

Branched alkanes (iso- and anteiso-alkanes) accumulated to comparable relative amounts in category I fruit cuticles (wild type, 32%; lecer6, 42% of total wax), followed by a sharp decrease in category II (wild type, 6%; lecer6, 3% of total wax). The deposition of long-chain aldehydes (C24, C26, C32) was exclusively seen with the wild-type wax, starting in category II and reaching its maximum in category VII. Total wax load, which peaked for both lecer6 and wild-type fruits in category V, slightly declined in categories VI and VII. However, the strongest augmentation of wax accumulation was marked by the transition from category I to category II. During fruit ripening, the total soluble fruit wax of both lines increased by a factor of up to 6, whereas the final cuticular wax load of the lecer6 fruits was only slightly, although significantly, decreased in comparison to wild-type fruits (wild type, 13.75 ± 1.14 μg cm−2; lecer6, 10.89 ± 1.53 μg cm−2; P = 0.01, t = 3.5).

Compositional Changes of Specific Wax Constituents during Fruit Development

A closer, more detailed look at the specific composition of the different compound classes allowed distinct evaluation of differences between the wild type and lecer6 mutant, as well as among the seven fruit developmental categories (Fig. 4). In the wild type and lecer6 mutant, the most striking change in wax composition occurred between category I and category II, where cyclic triterpenoids and sterol derivatives accumulated. The amyrins (α-, β-, and δ-amyrin; Fig. 4, composition nos. 1–4) accounted for about 76% to 91% of the cyclic wax constituents in all categories. In both lines, β-amyrin and δ-amyrin occurred in category II as the most prominent triterpenoids. During transition from category II to III, only wild-type fruits exhibited a 2-fold reduction of the α- and δ-amyrin coverage from 0.82 μg cm−2 to 0.42 μg cm−2 and from 1.40 μg cm−2 to 0.77 μg cm−2, respectively. Only β-amyrin accumulated to about 2.68 μg cm−2. In category II fruits of the lecer6 mutant, α- and β-amyrin reached values of 1.53 μg cm−2 and 2.17 μg cm−2, respectively, whereas δ-amyrin accumulated to 2.92 μg cm−2.

Figure 4.

Cuticular wax constituents of ‘MicroTom’ wild-type (A) and LeCER6-deficient (B) fruits assigned to seven developmental categories extracted by chloroform dipping. Triterpenoids and sterol derivatives are numbered as follows: 1, α-amyrin; 2, β-amyrin; 3, β-amyrin derivative; 4, δ-amyrin; 5, cholesterol; 6, lanosterol; 7, multiflorenol; 8, β-sitosterol; 9, stigmasterol; 10, taraxasterol and ψ-taraxasterol; 11, taraxerol; 12, lupeol; 13, lupeol derivative I; 14, lupeol derivative II; 15, unknown triterpenoid. Carbon chain lengths are shown for n-alkanes, iso- and anteiso-alkanes, alkenes, aldehydes, primary alkanols, primary alkenols, primary alkadienols, alkanoic acids, and dihydroxyalkanoic acids. Data represent means ± sd (n = 3–6).

The sterols cholesterol (Fig. 4; composition no. 5), lanosterol (6), multiflorenol (7), stigmasterol (9), taraxasterol, ψ-taraxasterol (10), and lupeol derivative I (13) were identified as common constituents of wild-type and lecer6 wax. Exclusively in the wild-type fruit, β-sitosterol (8) and taraxerol (11) were detected, whereas the occurrence of lupeol (12), lupeol derivative II (14), and an unidentified triterpenoid compound (15) was restricted to the cuticular wax of lecer6 fruits. The amounts of lanosterol, multiflorenol, taraxasterol, ψ-taraxasterol, and lupeol derivative I were distinctly increased in the lecer6 mutant fruit cuticular wax in categories II to VII.

During the early stages of fruit development (categories I–III), n-alkanes with chain lengths of C29 to C31 accumulated in the wild type, whereas this was not the case in the lecer6 mutant. On the contrary, total quantities of n-alkanes in the lecer6 wax were strikingly reduced during the transition from category I (29% of total wax) to category II (2% of total wax), which was in parallel with the sharp decline of iso- and anteiso-alkanes in both the ‘MicroTom’ wild type and lecer6 mutant.

In category III, a qualitative change was mirrored by the increase of n-alkanes in wild-type wax with chain lengths of C32 and C33, whereas the n-alkane composition of the lecer6 mutant remained unaffected. In parallel, alkenes (C33 and C35), which were not detected in the wax of lecer6, were present in wild-type wax. Likewise, primary alkanols started to accumulate in the wild type in category III, whereas the cuticular deposition of their mutant wax counterparts remained unchanged. Unlike the wild type, lecer6 fruit cuticles accumulated dihydroxyalkanoic acids (C22 and C24) in categories II to III.

Long-chain alkanoic acids (C20–C30) were apparent in the fruit cuticular wax of both lines in categories II to VII. Throughout categories I to VI, the overall amount of alkanoic acids was increased in the lecer6 cuticular wax when compared to the wild type. Most strikingly, the spectrum of alkanoic acids occurring was narrowed to mainly C24 and C26 in the wild type, whereas the lecer6 mutant cuticle contained alkanoic acids with chain lengths from C20 to C27 in different amounts. In the wild type, alkanoic acids started to accumulate in category IV, peaking in category VII, whereas the lecer6 mutant exhibited elevated levels already in category II, peaking in category V.

Spearman's correlation of ranks resulted in significant negative correlation between permeance for water and the cuticular accumulation of n-alkanes (R2 = −0.58; P < 0.05) throughout all ripening categories of ‘MicroTom’ wild-type and ‘MicroTom’ lecer6 fruits. A nonsignificant correlation coefficient was obtained for the correlation between water permeance and amounts of triterpenoid and sterol derivatives (R2 = 0.23).

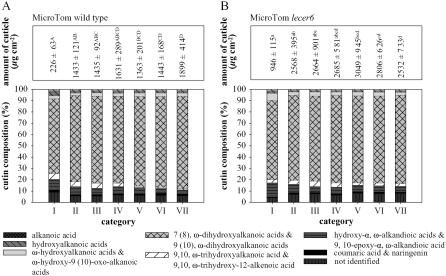

Chemical Composition of the Cutin Polymer Matrix during Fruit Development

The chemical composition of the cutin polymer was followed over the selected developmental stages of ‘MicroTom’ wild-type and lecer6 mutant fruits (Fig. 5). The relative proportions of different cutin monomers from lecer6 and wild-type cuticles were largely comparable. The dominating cutin monomers in both lines were ω-dihydroxyalkanoic acids. In category VII, they comprised 82% of wild-type and 78% of lecer6 cutin. For both, the major compound was 9 (10), ω-dihydroxyhexadecanoic acid contributing 61% to 80% to the wild-type and 67% to 76% to lecer6 cutin. During the course of fruit ripening, the proportion of ω-dihydroxyalkanoic acids increased by 16% in wild type and 8% in lecer6. Likewise, the proportion of α, ω-alkandioic acids decreased from category I to VII by about 50% in wild type and lecer6. The overall proportion of phenolic compounds, like coumaric acid and naringenin, did not exhibit vast changes during fruit ripening in both lines. Whereas coumaric acid decreased during fruit ripening, naringenin started to accumulate in early breaker fruits (category III). Between wild-type and lecer6 cuticles, a striking difference became discernible regarding the total weight of enzymatically isolated fruit cuticles. Throughout all developmental stages, lecer6 cuticles exhibited higher weights per fruit surface area (up to 4-fold in category I) than wild-type cuticles. Nevertheless, for both lines, cuticle weights increased to the same extent from category I to II and remained more or less constant during fruit maturation.

Figure 5.

Total amount of cuticle and relative cutin compositions of ‘MicroTom’ wild-type (A) and LeCER6-deficient (B) fruits of seven different ripening categories. Cuticle amounts of different categories within each line were compared with a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and subsequent multiple comparison of ranks; significant differences are marked with different letters (P < 0.05). Data are shown as means ± sd (n = 6).

DISCUSSION

A number of previous studies have focused on the relationship between wax characteristics and transpirational barrier properties of the cuticle. Geyer and Schönherr (1990), as well as Riederer and Schneider (1990), analyzed the effects of various growth conditions on the composition of Citrus aurantium leaf cuticles and their water permeability. Hauke and Schreiber (1998) demonstrated ontogenetic and seasonal modifications of wax composition and cuticular transpiration properties in ivy (Hedera helix) leaves. Jetter and Schäffer (2001) studied ontogenetic changes in the composition of P. laurocerasus adaxial leaf epicuticular waxes. Whereas the overall amounts of Prunus leaf waxes increased steadily, several distinct shifts in wax composition occurred in the course of leaf growth and maturation. The authors concluded from their data that such dynamic changes apparently reflect a defined developmental program that regulates biosynthesis and accumulation of cuticular wax constituents. Jenks et al. (1996) analyzed leaf and stem epicuticular wax composition of Arabidopsis wild type and of different wax mutants during development. Because a reliable astomatous plant model system was lacking, which would allow the functional analysis of cuticles from plants with defined genetic modifications, all attempts to correlate water permeance with the qualitative or quantitative composition of plant cuticular waxes have failed so far (Riederer and Schreiber, 1995, 2001).

In a recent study, Bauer et al. (2004b) demonstrated that the quantitative composition of tomato fruit waxes considerably depends on the cultivar assayed and the stage of ripening. To elucidate the quantitative and qualitative modifications of cuticular wax composition during fruit maturation and its functional impact on the fruit cuticular water barrier properties, the composition of fruit waxes of the dwarf tomato ‘MicroTom’ and its lecer6 mutant (Vogg et al., 2004) was followed over seven distinct stages of fruit development. The ripening categories employed corresponded to stages of the ripening process that could easily be differentiated visually according to fruit size and color.

Cuticular Water Permeability and Wax Component Accumulation during Tomato Fruit Development

In this study, the cuticles of ‘MicroTom’ fruits were found to have cuticular water permeances between 47.5 ± 25.4 × 10−5 m s−1 in immature green fruits of category I and 0.9 ± 0.2 × 10−5 m s−1 (vapor based) in red overripe fruits of category VII. Values obtained for wild-type and lecer6 fruits of categories II to VII were in a similar range as those for isolated mature tomato fruit cuticles from previous investigations, ranging from 2 × 10−5 m s−1 to 14 × 10−5 m s−1 (Schönherr and Lendzian, 1981; Becker et al., 1986; Lendzian and Kerstiens, 1991; Schreiber and Riederer, 1996; Vogg et al., 2004). Generally, category I fruits exhibited clearly higher values. The overall cuticular water permeance of ‘MicroTom’ wild-type fruit cuticles decreased during fruit development, reaching minimal values in early breaker to red overripe fruits (categories III–VII; Table I). Similar developmental patterns concerning cuticular transpiration were described for the tomato cultivars ‘Bonset’ and ‘Hellfrucht 1280’ (Haas, 1974). Likewise, permeances for lecer6 fruits remained more or less constant in categories III to VII. In wild-type and lecer6 fruits, the decrease of permeance in categories I to III was paralleled by an increase of total extractable waxes. Considering wax amounts and water permeances, our results suggest the existence of a negative correlation between water permeance and wax coverage in ‘MicroTom’ fruits. Nonetheless, wax extractions of red ripe (category VI) wild-type and lecer6 fruits yielded comparable amounts of total extractable waxes, although the water permeance of lecer6 cuticles was increased 8-fold when compared to the wild type. Hence, like in other systems (Riederer and Schreiber, 2001), our data indicate that cuticular wax quality rather than its quantity predominantly affects the barrier properties of ‘MicroTom’ fruit cuticles.

In accordance with our results, Bauer et al. (2004b) demonstrated a continuous increase in wax coverage in the developmental course from mature green to red ripe fruits in the tomato ‘RZ 72-00’. In an earlier publication, Baker et al. (1982) had sampled tomato fruits (‘Michigan Ohio’) of distinct sizes, ranging from immature green to firm red. Their data indicate a continuous increase in total waxes, except in the mature green stage in which a transient decrease was observed. However, this decrease could not be corroborated with ‘MicroTom’ fruits used in this study. Surprisingly, the amounts of extractable total cuticular waxes in the late ripening categories VI and VII were slightly diminished in wild-type and mutant fruits and did not result in any increase of water permeance values. This further supports the suggested predominant significance of wax composition rather than amount for cuticular barrier properties of ‘ MicroTom’ fruits. In addition, almost identical permeance levels of lecer6 were paralleled by approximately 2-fold higher wax amounts present in the wild-type cuticle of category I fruits. Thus, more wax does not necessarily result in reduced permeance levels. The relation of wild-type to lecer6 fruit water permeance values changed dramatically in ripening category II, accompanied by a significant increase in total wax coverage of both lines. In wild-type fruits, this increase was largely caused by increasing amounts of n-alkanes and pentacyclic triterpenoids, whereas the lecer6 mutant, although accumulating cyclic triterpenoids in even higher quantities, exhibited a distinct reduction in n-alkanes and a slight increase in primary alkanols, alkanoic acids, and dihydroxyalkanoic acids. This emerging reduction of n-alkanes per fruit surface area in lecer6 fruits during transition from category I to II, possibly caused by the considerable surface expansion of the tomato fruits between these particular categories (Fig. 1), might be responsible for the observed switch in water permeance characteristics, resulting in elevated permeance values for the lecer6 mutant. Regardless of wax composition, decrease of cuticular water permeance may nonetheless be negatively correlated with the overall cuticular wax amount.

In category III, wild-type fruit wax exhibited continuous accumulation of n-alkanes (now mainly C31 and C33) and a distinct reduction of water permeance. Commencing with category IV, the amounts and specific compositions of n-alkanes in the wild-type wax, as well as the respective water permeance characteristics, remain more or less stable. According to this dataset, the barrier properties of the tomato fruit cuticle appear to be already largely determined in early breaker fruits (fruit ripening category III in this study), although overall fruit wax coverage has not yet reached its maximal values in both wild-type and lecer6 plants. Considering the chemical and functional differences between the wild type and lecer6 mutant, it can be inferred that, in ‘MicroTom’ fruits, the developmentally regulated distinct rise of cuticular n-alkane constituents is one of the major determinants of cuticular water permeance properties.

Impact of LeCER6 Deficiency on Cuticular Wax Component Accumulation

Biosynthesis of aliphatic wax constituents, starting with C18 fatty acid precursors, proceeds via sequential elongation steps followed by modification of functional groups (von Wettstein-Knowles, 1993; Hamilton, 1995; Kolattukudy, 1996; Post-Beittenmiller, 1996; Kunst and Samuels, 2003; Kunst et al., 2006). The ‘MicroTom’ lecer6 mutant is defective in a β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (LeCER6) activity, responsible for the elongation of VLCFAs. In lecer6 fruit wax of category II, the largely missing increase of n-alkanes with chain lengths beyond C28 indicates that the range of substrate specificity of LeCER6 could in fact encompass molecules with chain lengths beyond C28 and therefore might have been underestimated analyzing mature red fruits only (Vogg et al., 2004). The Arabidopsis AtCER6 β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase, encoded by a gene highly homologous to Lecer6, is responsible for the elongation of VLCFAs larger than 26 carbons (Millar et al., 1999; Fiebig et al., 2000; Hooker et al., 2002). The occurrence of branched iso- and anteiso-alkanes and n-alkanes with chain lengths of C25 to C33 in lecer6 mutant cuticles of category I suggests that, in early stages of fruit ontogeny, a β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase different from LeCER6 must have been involved in the biosynthesis of these particular constituents. In later developmental stages, the loss of LeCER6-function is obviously not complemented by functionally redundant enzymes. In the case of lecer6 fruit wax, cuticular accumulation of triterpenoids and sterol compounds, as well as the increased weight of the cuticular membrane, may serve as compensation for reduced amounts of n-alkanes. The biosynthetic apparatus of lecer6 fruits may not be flexible enough to respond to the loss of LeCER6 function in a way different from increasing the amounts of pentacyclic triterpenoids and sterol derivatives in categories II to V. Nevertheless, this increase mainly of amyrins is obviously not fully sufficient to functionally complement the lack of n-alkanes, finally resulting in an up to 8-fold increased cuticular water permeance.

Besides the dramatic differences concerning the accumulation of n-alkanes, the specific knockout of LeCER6 function appears to completely prevent the formation of alkenes (C33, C35), aldehydes (C24, C26, C32), alkenols (C24, C26), and alkadienols (C22, C24, C26) in lecer6 wax, most probably due to missing common precursor molecules. The differential accumulation of alkanoic acids with chain lengths of up to 27 carbons in the lecer6 mutant might reflect the accumulation of molecules that otherwise might have served as potential substrates for the missing LeCER6. As already deduced from the water permeance analyses, our data on the developmental sequence of cuticular wax composition indicate that major effects caused by the deficiency in the LeCER6 β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase are apparently not displayed until the fruit has entered the transition from fruit ripening category I to II.

Contribution of Different Cuticular Layers and Wax Constituents to the Transpiration Barrier

Most wax analyses and functional studies in the past did not differentiate between cuticular substructures. Recently, methods have been developed that allow the selective sampling of exterior (epicuticular) and internal (intracuticular) wax layers for chemical analyses (Jetter et al., 2000; Jetter and Schäffer, 2001). The permeability properties of epi- and intracuticular waxes might differ in relation to the strong chemical distinctions between these layers. Moreover, the cutin polymer not only serves as a matrix, but also may contribute to the transport characteristics of the cuticle. Therefore, it is desirable to assess to what extent the different cuticular compartments contribute to the overall transpiration barrier. Gum arabic treatment of fruit surfaces allows selective removal of the outermost epicuticular wax layer and assessment of its relevance for the permeance properties of tomato fruit cuticles in vivo (Vogg et al., 2004).

The composition of tomato fruit epicuticular waxes distinctly differs from intracuticular waxes as exclusively aliphatic components were detected in gum arabic samples obtained from wild-type and lecer6 fruits (Vogg et al., 2004). Because the increase of permeance following chloroform wax extraction was much greater than after gum arabic stripping of epicuticular waxes (Table I), it may be concluded that tomato fruit epicuticular waxes might play a smaller role in determining the cuticular barrier properties in comparison to the intracuticular wax fraction. However, the contribution of the epicuticular wax layer to the permeance properties of tomato fruit cuticles for water becomes more conspicuous when the cuticular resistance model is applied (Schönherr, 1976; Kerstiens, 2006). The resistance of the epicuticular wax layer (rECW) of ‘MicroTom’ red ripe wild-type fruits (category VI) contributes roughly 70% to total cuticular resistance (rCM), whereas the epicuticular waxes of lecer6 fruits of the same developmental stage account only for 44%. In line with this finding, the epicuticular waxes of sweet cherry fruit contribute to a similar extent (72%) to the total cuticular resistance (Knoche et al., 2000). According to this model, the striking difference in epicuticular resistance between wild-type and lecer6 fruits of category VI cannot simply be explained by the 2.5-fold reduced epicuticular wax coverage of lecer6. Hence, factors other than wax amount must be responsible for the decreased contribution of lecer6 epicuticular waxes to total cuticular resistance. In category I, the major portion of cuticular wax constituents found with ripe tomato fruits is not yet present. This might explain the almost identical permeance values for wild-type and lecer6 fruits of category I, not only after gum arabic stripping. The elevated permeances after chloroform dipping underline the significance of the intracuticular waxes of ‘MicroTom’ fruit cuticles as important factors determining fruit water retention capacities (Fig. 3).

The Cutin Matrix

Gum arabic treatment and chloroform dipping resulted in converging permeance values, distinctly reducing the ratio between permeances of wild-type and lecer6 fruits. In accordance with Vogg et al. (2004), this clearly reflects the functional significance of cuticular wax quality for the transpirational barrier properties of tomato fruit cuticles. The remaining differences between wild-type and lecer6 fruits after chloroform extraction are only in part attributable to the remaining 20% of the fruit surface area not subjected to chloroform extraction. Therefore, other additional factors must be involved in determining the transpiration barrier properties of the tomato fruit cuticle. This view is supported by the decreasing permeance values of wild-type and lecer6 fruits after chloroform dipping in the course of fruit maturation.

Assuming that the extraction efficiency of chloroform remains constant throughout the selected categories of fruit ripening, this effect might be explained with distinct modifications of cutin polymer composition and/or polymer cross-linking during fruit growth and maturation. However, the compositional analysis of ‘MicroTom’ cutin monomers revealed that both wild-type and lecer6 cuticles exhibited a similar compositional pattern of cutin polymer constituents, when fruit cuticles of the same developmental category were compared. This was not surprising because the loss of LeCER6 activity was not expected to exert direct effects on cutin matrix composition.

During fruit development, similar compositional changes were detected for wild-type and lecer6 cuticles. Our results are largely in accordance with data obtained from cuticles of ‘Michigan Ohio’ (Baker et al., 1982). By contrast, Haas (1974) reported that the cutin monomer composition of two different tomato cultivars remained virtually constant during fruit development. Nevertheless, maturation of tomato fruit cutin may entail structural changes resulting in lowered polarity and/or higher cross-linking and, therefore, reduced permeability to water (Schmidt et al., 1981). Although this decrease in categories III to VII becomes evident exclusively after chloroform extraction, the distinct compositional changes of the cutin polymer during fruit maturation might play a role as well. Thus, in intact wild-type and lecer6 fruits, modifications of the cutin polymer appear to be largely masked by the more effective barrier properties of epi- and intracuticular waxes. Even the distinctly higher weights of lecer6 fruit cuticles, most probably reflecting an increased amount of cutin, are apparently not sufficient to largely affect transpiration barrier properties of the mutant cuticle. After complete removal of the cuticle, wild-type and lecer6 fruits still exhibited significantly distinct permeance values. The dimension of these differences was largely comparable to those observed after chloroform dipping. This suggests that the distinct cuticular permeance of wild-type and lecer6 fruits after removal of the cuticular waxes by chloroform treatment might be largely cuticle independent.

Wax Composition and Cuticular Barrier Properties

Geyer and Schönherr (1990) suggested that the molecular structure of cuticular waxes might be a much more important determinant of permeability than either wax amount or wax composition. Therefore, a model for the molecular structure of plant cuticular waxes was developed (Riederer and Schneider, 1990; Reynhardt and Riederer, 1994; Riederer and Schreiber, 1995). According to this model, the wax barrier consists of impermeable platelets of crystalline zones embedded in a matrix of amorphous material. Water diffusion occurs only in the amorphous volume fractions, whereas crystallites, increasing the tortuosity of the diffusion path (Buchholz, 2006), are inaccessible. Based on x-ray diffraction studies, it was postulated that triterpenoids are localized exclusively in the amorphous zones (Casado and Heredia, 1999). Hence, for lecer6 fruits, a reduction in n-alkanes, together with the increase in triterpenoids, should create amorphous zones at the expense of crystalline domains. This shift in overall crystallinity might be the actual reason for the increase in cuticular transpiration. Nevertheless, this model exclusively considers the lipophilic path of transport and does not integrate compositional changes either of the cutin matrix or of other constituents of the cuticle. In a previous study, Haas (1974) suggested that cuticular transpiration of tomato fruits might be strongly promoted by hydrophilic constituents of the cuticle, like cellulose or other polysaccharides. Such compounds might be involved in the formation of polar pores and therefore enhance cuticular transpiration. Previous studies have predicted that, in general, more polar constituents embedded in the cuticle could increase its permeability (Goodwin and Jenks, 2005). In fact, several cuticular constituents could provide polar functional groups, which may form the basis of polar aqueous pores. However, the nature of such pores remains to be elucidated (Schreiber, 2006). Nevertheless, the overriding role of cuticular waxes for the transport-limiting barrier of the tomato cuticular membrane is evident because the cuticular water permeability was increased by one order of magnitude after chloroform dipping of intact fruits. This role holds true for lecer6, although the contribution of the largely modified cuticular waxes was significantly reduced. Even Haas (1974) argued that predominantly epi- and intracuticular waxes are responsible for the observed reduction of cuticular water permeability during the course of fruit growth and ripening. With regard to the hydrophilic pathway, cuticular waxes might block potential polar paths and the removal of waxes might increase the pore area or decrease the tortuosity of the hydrophilic pathway, thereby increasing water permeability (Popp et al., 2005). Chloroform extraction of astomatous pear leaf cuticular membranes, however, resulted in only 2- to 3-fold increased rates of penetration for calcium chloride, being restricted to the polar pathway. This showed clearly that the aqueous pores present in extracted cuticles were not covered or plugged up by cuticular waxes (Schönherr, 2000). As yet, we can only speculate that individual, eventually more polar, constituents of cuticular waxes might interact with polar pores and, in turn, affect the transpiration characteristics of the cuticle.

CONCLUSION

The results presented here suggest an important role for cuticular wax constituents, like long-chain n-alkanes, in the determination of cuticular water permeance characteristics over the developmental course of tomato fruit ripening. We demonstrate a developmental and functional relationship between water permeance of intact tomato fruit cuticles and a qualitative trait of their cuticular waxes. Nevertheless, the respective roles of the hydrophilic and polar pathways in determining tomato fruit cuticular water barrier properties remain to be elucidated. Future experimental approaches have to address the molecular dissection of the developmental processes of tomato fruit ripening, with particular emphasis on genes and proteins involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis. The contribution of the numerous cuticular wax components to cuticular water permeability should be elucidated. Microarray studies are under way in the author's laboratory to identify genes that are part of the developmental program controlling tomato fruit wax accumulation. These, in combination with localization studies (e.g. RNA in situ hybridizations), might help to further substantiate the chemical and structural basis of the water barrier properties of primary plant surfaces.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Fruits from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) ‘MicroTom’ were used. Both wild-type and Ac/Ds transposon-tagged plants with a deficiency in a fatty acid β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (LeCER6) were used. Identification and characterization of this knockout insertional mutant has been reported previously (Vogg et al., 2004). Plants were cultivated in a growth chamber with 75% relative humidity, a 14-h photoperiod at 450 μmol m−2 s−1, and a temperature of 22°C/18°C. Plants were watered daily and fertilized with 1‰ (w/v) Hakaphos Blau nutrient solution (Compo) once a week.

Categorization of Tomato Fruits According to Their Developmental Stage

Tomato fruits were categorized on the basis of their size and pigmentation. Wild-type and LeCER6-deficient fruits were classified into comparable categories (Fig. 1). Immature green fruits of category I, collected between 7 and 10 d after flowering (DAF), had a fruit surface area not exceeding 0.54 ± 0.14 cm2 for the wild type and 0.51 ± 0.11 cm2 for the lecer6 mutant. This particular developmental stage was selected because it was the earliest suitable for determination of fruit permeance for water and chloroform wax extraction. Category II fruits, representing mature green fruits, were harvested between 25 to 30 DAF, exhibiting fruit surface areas of 8.61 ± 1.24 cm2 and 5.67 ± 1.04 cm2, respectively. For categories III to VI, early breaker, breaker, orange, and red ripe pigmentation rather than fruit size was the major criterion of categorization. At about 40 DAF, all fruits had entered into category VII (red overripe). On the average, fruits of the lecer6 mutant remained slightly smaller than their wild-type counterparts of comparable age and pigmentation.

Characterization of Cuticular Water Transport

Cuticular water permeance was determined for intact ‘MicroTom’ fruits of different developmental stages. The attachment site of the pedicel was sealed with paraffin (Merck). The amount of water transpired versus time (five to eight data points per individual fruit) was measured using a balance with a precision of 0.1 mg (Sartorius AC210S). Cuticular water flow rates (F; in g s−1) of individual fruits were determined from the slope of a linear regression line fitted through the gravimetric data. Coefficients of determination (r2) averaged 0.999. Fluxes (J; in g m−2 s−1) were calculated by dividing F by total fruit surface area as determined from the average of vertical and horizontal diameters by assuming a spherical shape of the fruit. Between measurements, the fruits were stored at 25°C over dry silica gel (Applichem). Under these conditions, the external water vapor concentration was essentially zero. The vapor phase-based driving force (Δc) for transpiration is, therefore, 23.07 g m−3. For calculating water permeance (P, in m s−1) based on water vapor concentration, J was divided by Δc.

In addition, cuticular water permeance of ‘MicroTom’ fruits after different modifications of the cuticular membrane was analyzed: For quantitative removal of the epicuticular wax layer, a thin film of aqueous gum arabic (Roth) was applied to the fruit surface. After 1 h, the dried polymer, including the outermost epicuticular waxes, was mechanically removed. To extract the solvent-soluble epi- and intracuticular waxes, fruits were dipped in chloroform (Roth) at room temperature for 1 (category I) or 2 (categories II–VII) min. To avoid solvent penetration at the stem scar, only about 80% of each fruit surface was dipped. Alternatively, the tomato fruit was peeled off completely.

Fruit Wax Extraction for Gas Chromatographic Analysis

To extract total wax mixtures, intact tomato fruits of category I were immersed for 1 min and fruits of categories II to VII for 2 min in chloroform (Roth) at room temperature. Approximately 80% of the fruit surfaces were dipped to avoid solvent penetration at the stem scar. As an internal standard, n-tetracosane (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to all extracts and the solvent was evaporated under a continuous flow of nitrogen. Lipids from internal tissues with chain lengths of C16 and C18 could not be detected in these extracts. Dipping efficiency was tested in a series of experiments with extraction times ranging from 5 s to 10 min.

Fruit Cutin Extraction for Gas Chromatographic Analysis

The cuticular membranes of tomato fruits were isolated enzymatically with pectinase (Trenolin Super DF; Erbslöh) and cellulase (Celluclast; Novo Nordisk AIS) in 20 mm citrate buffer, pH 3.0, supplemented with 1 mm sodium azide (Schönherr and Riederer, 1986), initially washed with 10 mm borax buffer (disodium tetraborate decahydrate; Roth) at pH 9.18 and then with deionized water. Total wax was removed by immersing the air-dried membranes in chloroform (Roth) at room temperature. The isolated, wax-free cuticles were transesterified with BF3-methanol (approximately 1.3 m boron trifluoride in methanol; Fluka) at 70°C overnight to release methyl esters of cutin acid monomers and phenolics. Sodium chloride-saturated aqueous solution (Applichem), chloroform, and, as an internal standard, n-dotriacontane (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to all reaction mixtures. From this two-phase system, the depolymerized transmethylated cutin components were extracted three times with chloroform. The combined organic phases were dried over sodium sulfate (anhydrous; Applichem). All extracts were filtered and the organic solvent was evaporated under a continuous flow of nitrogen.

Analysis of Fruit Wax and Fruit Cutin by Gas Chromatography

Prior to gas chromatographic analysis, hydroxyl-containing wax and cutin compounds were transformed into the corresponding trimethylsilyl derivatives using N,O-bis-trimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide (Macherey-Nagel) in pyridine (Merck). The qualitative composition was identified with temperature-controlled capillary gas chromatography (6890N; Agilent Technologies) and on-column injection (30 m DB-1, 320 μm i.d., df = 1 μm; J&W Scientific) with helium carrier gas inlet pressure programmed at 50 kPa for 5 min, 3.0 kPa min−1 to 150 kPa, and at 150 kPa for 30 min using a mass spectrometric detector (70 eV; m/z 50–750; 5973N; Agilent Technologies). Separation of the wax and cutin mixtures was achieved using an initial temperature of 50°C for 2 min, raised by 40°C min−1 to 200°C, held at 200°C for 2 min, and then raised by 3°C min−1 to 320°C and held at 320°C for 30 min. Quantitative composition of the mixtures was studied using capillary gas chromatography (5890 II; Hewlett-Packard) and flame ionization detection under the same gas chromatographic conditions as above, but with hydrogen as carrier gas. Single compounds were quantified against the internal standard.

Statistical Analyses

Data on permeance for water, cuticle, and wax quantities within ‘MicroTom’ wild type and within ‘MicroTom’ lecer6 were tested by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference mean-separation test for unequal n or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and subsequent multiple comparisons of ranks. One-way ANOVA was only used when homogeneity of variances was given. Accordingly, comparisons between both lines within each fruit-ripening category were tested with Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney U-test. Statistical analyses were performed with STATISTICA 7.1 (StatSoft).

Spearman's correlation of ranks was used to estimate the correlation coefficient between permeance for water (m s−1), amount of n-alkanes and triterpenoids, and sterol derivatives (μg cm−2) of ‘MicroTom’ fruits of all ripening categories (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Lena Reinhardt for excellent technical assistance, Jutta Winkler-Steinbeck for plant care, and Avraham A. Levy (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) for providing us with the lecer6 mutant.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. VO 934–1–3) and by the Sonderforschungsbereich 567.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Ulrich Hildebrandt (ulrich.hildebrandt@botanik.uni-wuerzburg.de).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

References

- Baker EA, Bukovac J, Hunt GM (1982) Composition of tomato fruit cuticle as related to fruit growth and development. In DF Cutler, KL Alvin, CE Price, eds, The Plant Cuticle. Academic Press, London, pp 33–44

- Bauer S, Schulte E, Thier HP (2004. a) Composition of the surface wax from tomatoes. I. Identification of the components by GC/MS. Eur Food Res Technol 219 223–228 [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Schulte E, Thier HP (2004. b) Composition of the surface wax from tomatoes. II. Quantification of the components at the red ripe stage and during ripening. Eur Food Res Technol 219 487–491 [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Kerstiens G, Schönherr J (1986) Water permeability of plant cuticles: permeance, diffusion and partition coefficients. Trees (Berl) 1 54–60 [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz A (2006) Characterisation of the diffusion of nonelectrolytes across plant cuticles—properties of the lipophilic pathway. J Exp Bot 57 2501–2513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt M, Riederer M (2006) Cuticular transpiration. In M Riederer, C Mueller, eds, Biology of the Plant Cuticle. Annual Plant Reviews 23. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 292–311

- Cameron KD, Teece MA, Smart LB (2006) Increased accumulation of cuticular wax and expression of lipid transfer protein in response to periodic drying events in leaves of tree tobacco. Plant Physiol 140 176–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado CG, Heredia A (1999) Structure and dynamics of reconstituted cuticular waxes of grape berry cuticle (Vitis vinifera L.). J Exp Bot 50 175–182 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Goodwin SM, Boroff VL, Liu X, Jenks MA (2003) Cloning and characterization of the wax2 gene of Arabidopsis involved in cuticle membrane and wax production. Plant Cell 15 1170–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M, LeThiec D, Garrec JP (1997) An investigation into the effects of ozone and drought, applied singly and in combination, on the quantity and quality of the epicuticular wax of Norway spruce. Plant Physiol Biochem 35 447–454 [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel E, Levy AA (2002) Tomato mutants as tools for functional genomics. Curr Opin Plant Biol 5 112–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig A, Mayfield JA, Miley NL, Chau S, Fischer RL, Preuss D (2000) Alterations in CER6, a gene identical to CUT1, differentially affect long-chain lipid content on the surface of pollen and stems. Plant Cell 12 2001–2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer U, Schönherr J (1990) The effect of the environment on the permeability and composition of Citrus leaf cuticles. I. Water permeability of isolated cuticular membranes. Planta 180 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gniwotta F, Vogg G, Gartmann V, Carver TLW, Riederer M, Jetter R (2005) What do microbes encounter at the plant surface? Chemical composition of pea leaf cuticular waxes. Plant Physiol 139 519–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SM, Jenks MA (2005) The plant cuticle involvement in drought tolerance. In MA Jenks, PM Hasegawa, eds, Plant Abiotic Stress. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 14–36

- Goodwin SM, Rashotte AM, Rahman M, Feldmann KA, Jenks MA (2005) Wax constituents on the inflorescence stems of double eceriferum mutants in Arabidopsis reveal complex gene interactions. Phytochemistry 66 771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DC, Percy KE, Riding RT (1998) Effect of enhanced UV-B radiation on adaxial leaf surface micromorphology and epicuticular wax biosynthesis of sugar maple. Chemosphere 36 853–858 [Google Scholar]

- Haas K (1974) Untersuchungen zum chemischen Aufbau der Cuticula während der Organogenese von Blättern und Früchten sowie zur Cuticular transpiration. PhD thesis. University of Hohenheim, Hohenheim, Germany

- Hamilton RJ (1995) Analysis of waxes. In RJ Hamilton, ed, Waxes: Chemistry, Molecular Biology and Functions, Vol. 8. The Oily Press, Dundee, Scotland, pp 311–342

- Hauke V, Schreiber L (1998) Ontogenetic and seasonal development of wax composition and cuticular transpiration of ivy (Hedera helix L.) sun and shade leaves. Planta 207 67–75 [Google Scholar]

- Heredia A (2003) Biophysical and biochemical characteristics of cutin, a plant barrier biopolymer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1620 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker TS, Millar AA, Kunst L (2002) Significance of the expression of the CER6 condensing enzyme for cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129 1568–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GM, Baker EA (1980) Phenolic constituents of tomato fruit cuticles. Phytochemistry 19 1415–1419 [Google Scholar]

- Jeffree CE (1996) Structure and ontogeny of plant cuticles. In G Kerstiens, ed, Plant Cuticles: An Integrated Functional Approach. BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd., Oxford, pp 33–82

- Jenks MA, Tuttle HA, Feldmann KA (1996) Changes in epicuticular waxes on wild type and eceriferum mutants in Arabidopsis during development. Phytochemistry 42 29–34 [Google Scholar]

- Jetter R, Kunst L, Samuels AL (2006) Composition of plant cuticular waxes. In M Riederer, C Mueller, eds, Biology of the Plant Cuticle. Annual Plant Reviews 23. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 145–181

- Jetter R, Schäffer S (2001) Chemical composition of the Prunus laurocerasus leaf surface. Dynamic changes of the epicuticular wax film during leaf development. Plant Physiol 126 1725–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetter R, Schäffer S, Riederer M (2000) Leaf cuticular waxes are arranged in chemically and mechanically distinct layers: evidence from Prunus laurocerasus L. Plant Cell Environ 23 619–628 [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Han MJ, Lee DY, Lee YS, Schreiber L, Franke R, Faust A, Yephremov A, Saedler H, Kim YW, et al (2006) Wax-deficient anther1 is involved in cuticle and wax production in rice anther walls and is required for pollen development. Plant Cell 18 3015–3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstiens G (1996. a) Plant Cuticles—An Integrated Functional Approach. BIOS Scientific Publishers, Oxford

- Kerstiens G (1996. b) Cuticular water permeability and its physiological significance. J Exp Bot 47 1813–1832 [Google Scholar]

- Kerstiens G (2006) Water transport in plant cuticles: an update. J Exp Bot 57 2493–2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstiens G, Schreiber L, Lendzian J (2006) Quantification of cuticular permeability in genetically modified plants. J Exp Bot 57 2547–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoche M, Peschel S, Hinz M, Bukovac MJ (2000) Studies on water transport through the sweet cherry fruit surface: characterizing conductance of the cuticular membrane using pericarp segments. Planta 212 127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolattukudy PE (1996) Biosynthetic pathways of cutin and waxes and their sensitivity to environmental stresses. In G Kerstiens, ed, Plant Cuticles—An Integrated Functional Approach. BIOS Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 83–108

- Kunst L, Jetter R, Samuels AL (2006) Biosynthesis and transport of plant cuticular waxes. In M Riederer, C Mueller, eds, Biology of the Plant Cuticle. Annual Plant Reviews 23. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 182–215

- Kunst L, Samuels AL (2003) Biosynthesis and secretion of plant cuticular wax. Prog Lipid Res 42 51–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendzian K, Kerstiens G (1991) Sorption and transport of gases and vapours in plant cuticles. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 121 65–128 [Google Scholar]

- Meissner R, Chaque V, Zhu Q, Emmanuel E, Elkind Y, Levy AA (2000) A high throughput system for transposon tagging and promoter trapping in tomato. Plant J 22 265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner R, Jacobson Y, Melamed S, Levyatuv S, Shalev G, Ashri A, Elkind Y, Levy AA (1997) A new model system for tomato genetics. Plant J 12 1465–1472 [Google Scholar]

- Millar AA, Clemens S, Zachgo S, Giblin EM, Taylor DC, Kunst L (1999) CUT1, an Arabidopsis gene required for cuticular wax biosynthesis and pollen fertility, encodes a very-long-chain fatty acid condensing enzyme. Plant Cell 11 825–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C (2006) Unraveling the complex network of cuticular structure and function. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederl S, Kirsch T, Riederer M, Schreiber L (1998) Co-permeability of 3H-labeled water and 14C-labeled organic acids across isolated plant cuticles. Plant Physiol 116 117–123 [Google Scholar]

- Pighin JA, Zheng H, Balakshin LJ, Goodman IP, Western TL, Jetter R, Kunst L, Samuels AL (2004) Plant cuticular lipid export requires an ABC transporter. Science 306 702–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp C, Burghardt M, Friedmann A, Riederer M (2005) Characterization of hydrophilic and lipophilic pathways of Hedera helix L. cuticular membranes: permeation of water and uncharged organic compounds. J Exp Bot 56 2797–2806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-Beittenmiller D (1996) Biochemistry and molecular biology of wax production in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 47 405–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynhardt EC, Riederer M (1994) Structures and molecular dynamics of plant waxes II. Cuticular waxes from leaves of Fagus sylvatica L. and Hordeum vulgare L. Eur Biophys J 23 59–70 [Google Scholar]

- Riederer M, Schneider G (1990) The effect of the environment on the permeability and composition of Citrus leaf cuticles. II. Composition of soluble cuticular lipids and correlation with transport properties. Planta 180 154–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riederer M, Schreiber L (1995) Waxes—the transport barriers of plant cuticles. In RJ Hamilton, ed, Waxes: Chemistry, Molecular Biology and Functions. The Oily Press, Dundee, Scotland, pp 130–156

- Riederer M, Schreiber L (2001) Protecting against water loss: analysis of the barrier properties of plant cuticles. J Exp Bot 52 2023–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riederer M (2006) Thermodynamics of the water permeability of plant cuticles: characterization of the polar pathway. J Exp Bot 57 2937–2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland O, Zheng H, Hepworth SR, Lam P, Jetter R, Kunst L (2006) CER4 encodes an alcohol-forming fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductase involved in cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 142 866–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel TK, Schönherr J, Schreiber L (2005) Size selectivity of aqueous pores in stomatous cuticles of Vicia faba leaves. Planta 221 648–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HW, Merida T, Schönherr J (1981) Water permeability and fine structure of cuticular membranes isolated enzymatically from leaves of Clivia miniata Reg. Z Pflanzenphysiol 105 41–51 [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J (1976) Water permeability of isolated cuticular membranes: the effect of cuticular waxes on diffusion of water. Planta 131 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J, Huber R (1977) Plant cuticles are polyelectrolytes with isoelectric points around three. Plant Physiol 59 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J, Lendzian K (1981) A simple and inexpensive method of measuring water permeability of isolated plant cuticular membranes. Z Pflanzenphysiol 102 321–327 [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J, Merida T (1981) Water permeability of plant cuticular membranes: the effects of humidity and temperature on the permeability of non-isolated cuticles of onion bulb scales. Plant Cell Environ 4 349–354 [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J, Riederer M (1986) Plant cuticles sorb lipophilic compounds during enzymatic isolation. Plant Cell Environ 9 459–466 [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J (2000) Calcium chloride penetrates plant cuticles via aqueous pores. Planta 212 112–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J (2006) Characterization of aqueous pores in plant cuticles and permeation of ionic solutes. J Exp Bot 57 2471–2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L, Riederer M (1996) Ecophysiology of cuticular transpiration: comparative investigation of cuticular water permeability of plant species from different habitats. Oecologia 107 426–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L (2006) Characterisation of polar paths of transport in plant cuticles. In M Riederer, C Mueller, eds, Biology of the Plant Cuticle. Annual Plant Reviews, Vol 23. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, pp 280–291

- Shepherd T, Griffiths DW (2006) The effects of stress on plant cuticular waxes. New Phytol 171 469–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturaro M, Hartings H, Schmelzer E, Velasco R, Salamini F, Motto M (2005) Cloning and characterization of GLOSSY1, a maize gene involved in cuticle membrane and wax production. Plant Physiol 138 478–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogg G, Fischer S, Leide J, Emmanuel E, Jetter R, Levy AA, Riederer M (2004) Tomato fruit cuticular waxes and their effects on transpiration barrier properties: functional characterization of a mutant deficient in a very-long-chain fatty acid β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase. J Exp Bot 55 1401–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wettstein-Knowles PM (1993) Waxes, cutin and suberin. In TS Moore, ed, Lipid Metabolism in Plants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 127–166

- Yamamoto N, Tsugane T, Watanabe M (2005) Expressed sequence tags from the laboratory-grown miniature tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) cultivar MicroTom and mining for single nucleotide polymorphisms and insertions/deletions in tomato cultivars. Gene 356 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]