Abstract

The effect of PGE2 EP3 receptors on injury size was investigated following cerebral ischemia and induced excitotoxicity in mice. Treatment with the selective EP3 agonist ONO-AE-248 significantly and dose-dependently increased infarct size in the middle cerebral artery occlusion model. In a separate experiment, pretreatment with ONO-AE-248 exacerbated the lesion caused by N-methyl-D-aspartic acid-induced acute excitotoxicity. Conversely, genetic deletion of EP3 provided protection against N-methyl-D-aspartic acid-induced toxicity. The results suggest that PGE2, by stimulating EP3 receptors, can contribute to the toxicity associated with cyclooxygenase and that antagonizing this receptor could be used therapeutically to protect against stroke- and excitotoxicity-induced brain damage.

Keywords: Cerebral ischemia, EP3 receptor agonist, G-protein-coupled receptors, neurotoxicity, NMDA

1. Introduction

Inflammation has been shown to play a major role in the pathological response and outcome of stroke and other central nervous system disorders (Huang et al., 2006; Lucas et al., 2006). Inflammation is mediated at least in part by prostaglandins (PGs), which are produced through the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway. PGs are secreted from a variety of cells in response to physiological or pathological insults (Doré et al., 2003; Minghetti, 2004) and mediate a variety of actions via specific membrane-bound receptors to maintain local homeostasis. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) mainly binds to a family of G-protein-coupled receptors known as EP receptors (Narumiya et al., 1999). The members of the EP receptor family, EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4, elicit their actions by altering cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) or intracellular calcium concentrations. EP1 activates phospholipase C and phosphatidylinositol turnover and stimulates the release of intracellular calcium via a Gi-coupled mechanism. EP2 and EP4 both signal through a Gs-coupled mechanism that stimulates adenylyl cyclase and increases intracellular levels of cAMP (Narumiya et al., 1999). The EP3 receptor, which has several isoforms (Bilson et al., 2004), mediates the activation of several signaling pathways, leading to changes in cAMP levels, calcium mobilization, and activation of phospholipase C (Namba et al., 1993; Narumiya et al., 1999). Of the isoforms identified in mouse, EP3α and EP3β are reported to be coupled to Gi protein, which leads to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, whereas EP3γ has both inhibitory and stimulatory effects on adenylyl cyclase and cAMP accumulation (Irie et al., 1994; Sugimoto et al., 1993).

It has been reported that EP3 receptors are expressed in glial cells after intrastriatal injection of quinolic acid in rats (Slawik et al., 2004). This finding implies a direct role for EP3 receptors in various neurodegenerative disorders, such as stroke and Alzheimer disease. In addition, Zacharowski and colleagues (Zacharowski et al., 1999) reported that ONO-AE-248, a selective EP3 agonist, prevented the forskolin-induced increase in cAMP in CHO cell lines. Recently, Yamazaki et al. (2005) showed that EP3 receptor protein expression was significantly elevated in placenta 24 h after ischemia-reperfusion injury. EP3 receptors also have been shown to participate in inflammatory reactions in a mouse model of pleurisy, a model of acute inflammation (Yuhki et al., 2004), and have been reported to trigger pulmonary edema induced by platelet-activating factor in rats (Goggel et al., 2002). In addition, activation of EP3 receptor by PGE2 in mice inhibits cAMP production in platelets and promotes platelet aggregation (Fabre et al., 2001).

We previously reported that in mice, the EP1 receptor plays a toxic role in transient cerebral ischemia and excitotoxicity models (Ahmad et al., 2006a), a finding further substantiated by Kawano et al. (2006), and that EP2 and EP4 receptor activation is protective in N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA)-induced excitotoxic lesions (Ahmad et al., 2005; Ahmad et al., 2006b). We also have evaluated the effects of the drug 1-OH-PGE1, which stimulates EP4 and to a lesser extent EP3, and found it to be neuroprotective in transient ischemia (Ahmad et al., 2006c) and oxidative stress after β-amyloid exposure in mouse primary cultured neurons (Echeverria et al., 2005).

Because previous studies have shown that the EP3 receptor significantly affects outcomes after ischemia-reperfusion injury in peripheral organs (Martin et al., 2005; Yamazaki et al., 2005; Zacharowski et al., 1999), our goal in this study was to determine the role of EP3 in brain injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury. Therefore, we investigated the effects of the EP3 agonist ONO-AE-248 [Ki estimated at 10000, 3700, 7.5, and 4200 for EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4, respectively (Kiriyama et al., 1997; Narumiya and FitzGerald, 2001; Suzawa et al., 2000)] on middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO)-induced infarct volume, relative cerebral blood flow (CBF), mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and other physiological parameters. Furthermore, since excitotoxicity is involved in the resulting injury caused by ischemia/reperfusion, we went on to determine the effect of ONO-AE-248 on lesion size after NMDA-induced toxicity. To confirm our results, we compared the NMDA-induced lesion volume in wildtype (WT) mice and in mice with a genetic deletion of the EP3 receptor.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and drugs

Studies were carried out on 8- to 10-week-old male C57BL/6 mice weighing 25 to 30 g obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Inc (Wilmington, MA). EP3 receptor knockout (EP3−/−) mice were provided by Shuh Narumiya, University of Kyoto, Japan, and genotypes were confirmed by PCR. All animal protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals were allowed free access to water and food before and after surgery. ONO-AE-248 was kindly donated by ONO Pharmaceuticals (Osaka, Japan).

2.2. Assessment of EP3 receptor protein expression in mouse brain

To address whether EP3 is present in mouse cortex and striatum, homogenates of the corticostriatal region of mouse brains were analyzed by Western blot, as described previously (Ahmad et al., 2006c). Protein concentrations were quantified by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Electrophoresis was performed on 12% polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). Blots were stained with Ponceau S Solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to verify that equal amounts of protein were loaded into each lane. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 before being incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit EP3 polyclonal antibody (1:500; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI). Blots were washed and incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and then developed with ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

2.3. Stereotactic injection

Mice were anesthetized with 3.0% halothane and maintained with 1.0–1.5% continuous flow of halothane in oxygen-enriched air. Then the mice were mounted on a stereotactic frame and injected with 0.2 μl of different doses of ONO-AE-248 (0.5 nmol, 2.5 nmol, or 5.0 nmol) or vehicle (DMSO) via a 1-μl Hamilton syringe (Reno, NV) into the right lateral ventricle as described previously (Ahmad et al., 2006a). After the injection, the needle was retracted slowly, the hole was plugged with bone wax, and the wound was sutured. Mice were then either transferred to another setup for the MCAO procedure or left in place for NMDA injection (see below).

2.4. MCAO and reperfusion

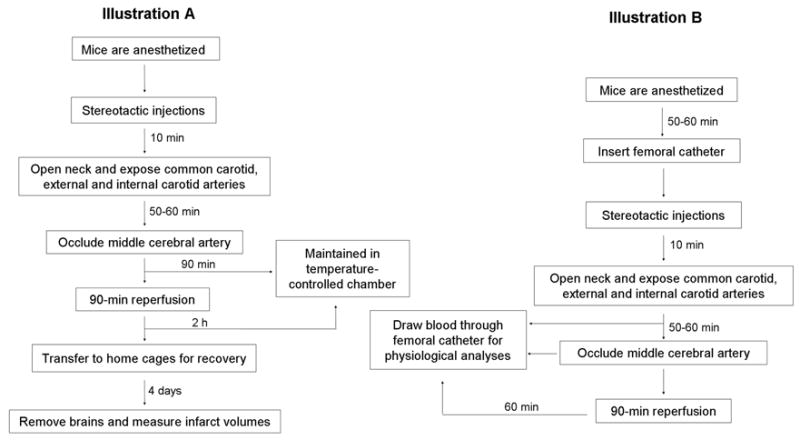

During the MCAO procedure (Fig. 1, Illustration A), mouse rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5°C by a heating pad, and anesthesia was maintained with continuous flow of halothane in oxygen-enriched air via a nose cone. Relative CBF was monitored with laser-Doppler flowmetry (Moor Instruments, Devon, England) by a flexible fiber optic probe affixed to the skull over the parietal cortex supplied by the MCA (2 mm posterior and 6 mm lateral to the bregma). MCAO was carried out under aseptic conditions with a silicone-coated nylon monofilament as described previously (Shah et al., 2006). The filament was left in position for 90 min, during which the incision was closed with sutures, anesthesia was discontinued, and the animals were transferred to a temperature-controlled chamber that maintains the body temperature of mice at 37.0 ± 0.5°C. At 90 min of occlusion, the mice were briefly reanesthetized with halothane, and reperfusion was achieved by withdrawing the filament and reopening the MCA. After the incisions were sutured, the mice were returned to the temperature-controlled chamber for 2 h before being transferred to their home cages for 4 days.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the protocol for middle cerebral artery occlusion surgery (Illustration A) and analysis of physiological parameters (Illustration B).

2.5. Quantification of infarct volume

Four days after MCAO surgery, mice (n = 9/dose) were deeply anesthetized, and their brains were harvested and sliced coronally into five 2-mm-thick sections. The sections were incubated with 1% 2,3,5-triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride (TTC) in saline for 20 min at 37°C. The area of infarcted brain, identified by the lack of TTC staining, was measured on the rostral and caudal surfaces of each slice and numerically integrated across the thickness of the slice to obtain an estimate of infarct volume in each slice (SigmaScan Pro, SPSS, Port Richmond, CA, USA). Volumes from all five slices were summed to calculate total infarct volume over the entire hemisphere and expressed as a percentage of the volume of the contralateral structure. Infarct volume was corrected for swelling by comparing the volumes in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. The corrected infarct volume was calculated as: volume of contralateral hemisphere − (volume of ipsilateral hemisphere − volume of infarct).

2.6. Analysis of physiological parameters

Measurement of physiological parameters was carried out in a group of mice separate from that used to assess infarct volume (Fig 1, Illustration B). Arterial blood samples collected via femoral catheter were analyzed for pH, PaO2, and PaCO2 before the occlusion, during occlusion, and 1 h after the occlusion. MABP was measured at the same time points by a pressure transducer connected to the femoral catheter.

2.7. Temperature regulation

A third cohort of mice was implanted with intra-abdominal radiofrequency probes [IPTT-200, Bio. Medic. Data System (BMDS), Seaford, DE] 7 days before injection of ONO-AE-248 (n = 5) or vehicle (n = 5). Core temperature was sampled every 10 min for the first 90 min after injection, and then once daily for 4 days at room temperature via receivers (The DAS-5002 Notebook System™; BMDS). This telemetry system minimizes stress and allows temperature control and monitoring in freely moving animals.

2.8. NMDA injection

To investigate the effect of NMDA toxicity in mice lacking the EP3 receptor, WT (n = 7) and EP3−/− (n = 8) mice were injected in the right striatum with 15 nmol NMDA or vehicle in a volume of 0.3 μl 20 min after being injected with ONO-AE-248, as reported earlier (Ahmad et al., 2006a). After injection, the hole was blocked and the wound sutured, as described above. After the surgical procedures, the animals were transferred to a temperature-regulated chamber to recover from anesthesia. Throughout the stereotactic procedures the rectal temperature of mice was monitored and maintained at 37.0±0.5°C.

2.9 Quantification of NMDA-induced lesion volume

At 48 h after NMDA injection, weight and rectal temperature of each mouse was recorded. Then, mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.2), under deep anesthesia. Brains were immediately removed, post-fixed in paraformaldehyde overnight, cryoprotected in sucrose (30%) for 3 days, and frozen in 2-methyl butane (pre-cooled over dry ice). Brain sections cut on a cryostat were collected on microscope slides and stained with Cresyl Violet to estimate lesion volume. Images of the brain sections were taken and analyzed with SigmaScan Pro 5.0 software (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA) as described previously (Ahmad et al., 2006b).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SigmaStat 2.0 (Systat Software Inc.). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used to calculate the difference between the groups. Core body temperature was analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by the Neuman-Keuls test. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Presence of EP3 receptor immunoreactivity in C57Bl6 mouse brain homogenates

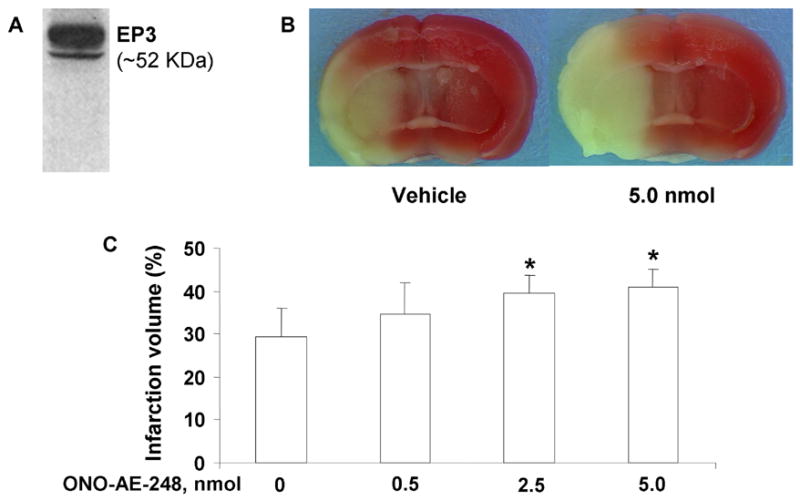

Western blot analysis of mouse brain homogenates revealed an immunoreactive band at the expected molecular weight for the mouse EP3 receptors (Fig. 2). The presence of EP3 receptors in the cerebrum is also supported by immunohistological and in situ hybridization studies in both rats and mice (Allen Brain Atlas, 2004; Engblom et al., 2004; Nakamura et al., 2000).

Fig. 2.

Effect of the EP3 receptor agonist ONO-AE-248 on percent corrected hemispheric infarct volumes in a mouse model of middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion. A: Western blot showing the presence of an immunoreactive profile corresponding to the estimated molecular weight of the mouse EP3 receptors in corticostriatal mouse brain homogenate. Mice were given ONO-AE-248 or vehicle in the lateral ventricle before being subjected to 90 min of occlusion and 4 days of reperfusion. B: Representative photographs of TTC-stained sections of mouse brain that were injected either with vehicle (left panel) or 5 nmol ONO-AE-248 (right panel) followed by MCAO and reperfusion. The unstained areas indicate the area of infarction. C: Hemispheric infarct volumes were significantly larger in mice treated with 2.5 and 5.0 nmol ONO-AE-248 than in vehicle-treated mice. The results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of 9 animals per group. *p < 0.05 compared with the vehicle-treated group.

3.2. Effect of ONO-AE-248 on infarct volume

Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of ONO-AE-248 before MCAO significantly enhanced hemispheric infarct volumes. Infarct volume increased by 17%, 34%, and 38% in mice treated with 0.5-, 2.5-, and 5.0-nmol doses, respectively, as compared with the vehicle-treated group (n = 9/dose). The increase was statistically significant only in the 2.5- and 5.0-nmol-treated groups (Fig. 2).

3.3. Cerebral blood flow

As estimated by laser-Doppler flowmetry, relative CBF decreased significantly in each group of mice after insertion of the nylon monofilament. Percent of baseline CBF was 18.0 ± 3.3 for the vehicle-treated group and 18.0 ± 3.7, 17.5 ± 2.0, and 17.0 ± 2.7 for the 0.5, 2.5, and 5.0 nmol-treated groups, respectively. The differences in CBF reduction were not significantly different.

3.4. Physiological parameters

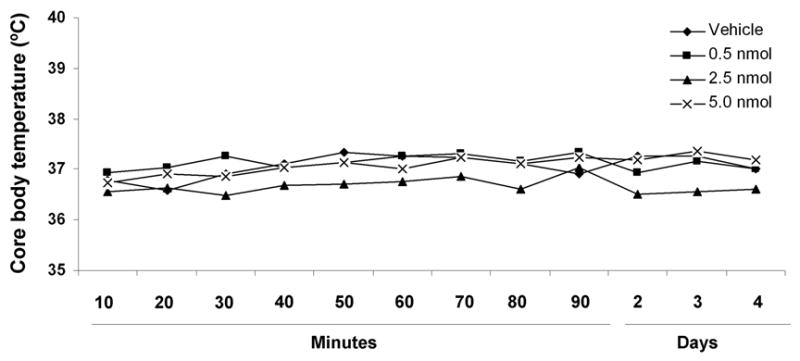

No statistically significant differences in pH, PaCO2, PaO2, or MABP were detected before ischemia, during ischemia, or during reperfusion among the groups of mice (Table 1). In a separate cohort of mice that did not undergo MCAO, we found that ONO-AE-248 did not affect core body temperature at any time during the 4-day experiment (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Effect of ONO-AE-248 on physiological parameters

| Parameter | Vehicle | 0.5 nmol | 2.5 nmol | 5.0 nmol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ischemia | ||||

| MABP | 76 ± 2 | 73 ± 2 | 81 ± 3 | 79 ± 2 |

| pH | 7.28 ± 0.39 | 7.29 ± 0.64 | 7.33 ± 0.93 | 7.19 ± 0.62 |

| PaCO2 | 46.6 ± 2.2 | 44.6 ± 6.3 | 45.6 ± 5.2 | 44.6 ± 3.8 |

| PaO2 | 138 ± 29 | 154 ± 10 | 142 ± 6 | 145 ± 9 |

| Ischemia | ||||

| MABP | 75 ± 2 | 73 ± 5 | 74 ± 7 | 74 ± 5 |

| pH | 7.25 ± 0.86 | 7.32 ± 0.64 | 7.25 ± 0.38 | 7.30 ± 0.54 |

| PaCO2 | 47.8 ± 6.1 | 41.8 ± 4.3 | 42.2 ± 2.2 | 43.4 ± 2.0 |

| PaO2 | 142 ± 14 | 135 ± 6 | 126 ± 5 | 127 ± 4 |

| Post-ischemia | ||||

| MABP | 74 ± 6 | 73 ± 4 | 78 ± 6 | 74 ± 6 |

| pH | 7.28 ± 0.83 | 7.23 ± 0.58 | 7.30 ± 0.51 | 7.30 ± 0.51 |

| PaCO2 | 46.6 ± 2.2 | 47.8 ± 3.2 | 44.2 ± 3.8 | 50.4 ± 4.7 |

| PaO2 | 139 ± 18 | 130 ± 13 | 134 ± 16 | 137 ± 26 |

MABP, mean arterial blood pressure

Fig. 3.

Core body temperature was recorded with an intra-abdominal radiofrequency probe every 10 min during the first 90 min after ONO-AE-248 injection and then once daily for 4 days while the mice were housed at room temperature. No significant differences in core body temperature were observed at any dose of ONO-AE-248 as compared with those of the vehicle-treated group. The results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of 5 animals per group.

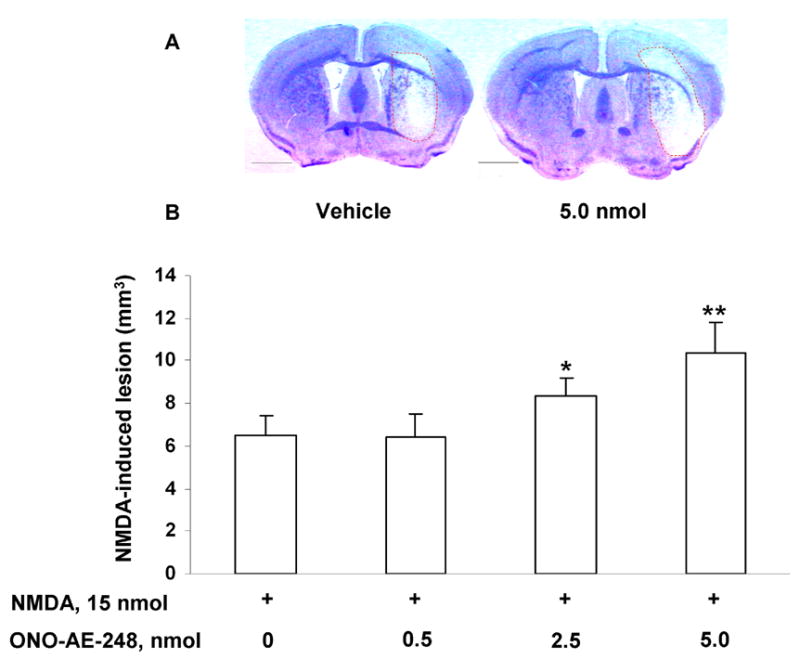

3.5. EP3 receptor agonist ONO-AE-248 exacerbates NMDA-induced brain lesion

Pretreatment of mice with ONO-AE-248 aggravated the brain injury caused by NMDA injection. ONO-AE-248 significantly and dose-dependently increased the NMDA-induced lesion size in groups treated with 2.5 (p < 0.02) and 5 nmol (p < 0.001), whereas the lowest dose of ONO-AE-248 (0.5 nmol) did not affect NMDA-induced toxicity (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Effect of EP3 receptor selective agonist ONO-AE-248 on NMDA-induced brain lesion in C57Bl/6 WT mice. A: Representative photographs of sections of mouse brain that were injected with either vehicle (left panel) or 5 nmol ONO-AE-248 (right panel) followed by NMDA, and stained with Cresyl Violet. B: Histograms representing volume of NMDA-induced brain injury. ONO-AE-248 significantly increased the injury volume observed in the groups pretreated with 2.5 nmol and 5.0 nmol ONO-AE-248 (n = 7/dose); however, no difference in brain lesion was observed at the lowest dose of 0.5 nmol as compared with NMDA alone (15 nmol, n =7). Values are reported as means ± S.D. *p < 0.02, **p < 0.001 when compared with the group given NMDA alone. Scale bar = 1000 μm.

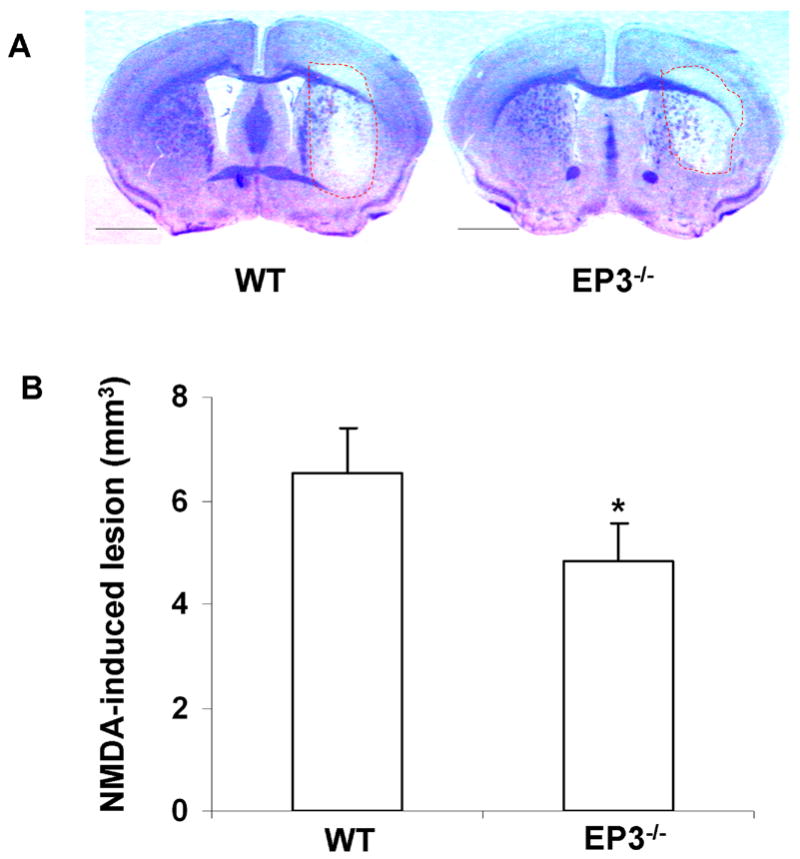

3.5. Genetic deletion of EP3 receptor protects brain from acute excitotoxicity

EP3−/− mice were found to be less susceptible to NMDA-induced toxicity, than the WT mice (Fig. 5). The mean lesion volume in the NMDA-treated EP3−/− mice was 26% smaller (p < 0.01) than that of the NMDA-treated WT mice.

Fig 5.

NMDA-induced toxicity in the brains of C57Bl/6 WT and EP3−/− mice. A single dose of NMDA (15 nmol) was injected into the right striatum of C57Bl/6 WT (n = 7) and EP3−/− mice (n = 8). A: Representative photographs of mouse brain sections injected with NMDA and stained with Cresyl Violet. B: Quantitative analysis showed that the lesion volume in EP3−/− mice was significantly smaller than that in WT mice. The lesion volume was attenuated by 26 ± 10% as compared with the WT mice. Values are reported as means ± S.D. *p < 0.01. Scale bar = 1000 μm.

4. Discussion

There have been some conflicting reports in the literature in regard to the role of EP3 receptors in health and disease; some investigators have reported that EP3 affords protection whereas others state that it aggravates toxicity. Considering that PGE2 is often called the “pro-inflammatory” prostaglandin, we have used the mouse models of cerebral ischemia and induced excitotoxicity to elucidate a better understanding of the function of the EP receptors and help resolve some of the contradictory findings. Our current study was designed to determine the role of EP3 in acute excitotoxicity and stroke. We found that 2.5- and 5.0-nmol doses of the selective EP3 receptor agonist ONO-AE-248 significantly exacerbated the lesion volume following NMDA injection and the infarct volume following transient ischemia, while none of the physiological parameters studied were significantly affected. We also found that genetic deletion of the EP3 receptor reduced the resulting lesion size after NMDA injection as compared to that observed in WT littermates. To our knowledge this is the first report to show that stimulation of the EP3 receptors in the brain exacerbates brain damage.

COX-2 is constitutively present at low levels but is highly inducible and suggested to be responsible for inflammatory reactions (Morham et al., 1995). Several groups have documented the induction of COX-2 after cerebral ischemia (Collaco-Moraes et al., 1996; Planas et al., 1995; Tomimoto et al., 2002). It is well established that pharmacologic inhibition of COX-2 activity and genetic deletion of COX-2 (Iadecola et al., 2001) are protective in cerebral ischemia, whereas COX-2 overexpression in a transgenic model is detrimental (Doré et al., 2003). However, when COX-2 was overexpressed in neurons of mice, we found that COX-2 inhibitors could not decrease the size of infarcts caused by cerebral ischemia (Doré et al., 2003). Moreover, recent clinical reports of the side effects associated with the COX-2 inhibitors led us to consider that a better strategy for treating ischemic injury might lay in modulating the PGs and PG receptors downstream of the COX pathway.

PGE2 has been reported to execute its toxic actions mainly via the EP3 receptor in a rat model of passive Heymann nephritis (Waldner et al., 2003). Furthermore, EP3 receptor and COX-2 immunoreactivity have been reported to colocalize and increase in rat placenta after ischemia-reperfusion of the uterine artery (Yamazaki et al., 2005). Therefore, it seems very likely that the EP3 receptor would be involved in ischemia-reperfusion injury in the brain.

We found that ICV injection of ONO-AE-248 did not produce detectable changes in the various physiological parameters monitored. In earlier studies, stimulation of the EP3 receptor with 17-phenyl trinor PGE2, sulprostone (EP1/EP3 agonists) (Jadhav et al., 2004) or ONO-AE-248 (Norel et al., 2004) was reported to cause vasoconstriction, but we did not observe significant changes in MABP at any dose of ONO-AE-248 tested under our experimental conditions. One possibility for this finding is that the effects might have been too short-lived or not large enough to be measured. Alternatively, the dissimilar results could stem from the use of different models; the latter studies were carried out in vitro in arteries dissected from either pig cerebral arteries (Jadhav et al., 2004) or human pulmonary arteries (Norel et al., 2004), whereas our experiments were conducted in vivo. Furthermore, 17-phenyl trinor PGE2 and sulprostone have high affinities for the EP1 receptor (14 and 4 nM, respectively) in addition to the EP3 receptor (21 and 0.6 nM, respectively), whereas ONO-AE-248 is highly selective toward EP3 receptor. In fact, ONO-AE-248 is estimated to be 1333 times more specific for EP3 than for EP1 (Kiriyama et al., 1997; Narumiya and FitzGerald, 2001; Suzawa et al., 2000).

Assessment of CBF by laser-Doppler flowmetry indicated that MCAO resulted in similar decreases in cortical perfusion throughout the ischemic period in vehicle-treated and drug-treated mice, suggesting that the mechanism by which EP3 affects the severity of the ischemic insult was not by altering blood flow with its stimulation by ONO-AE-248. These results predict a toxic role for EP3 by mechanisms other than increasing the ischemic insult.

The core body temperature was not significantly affected by ONO-AE-248 at any time during our experimental protocol. Although this result might appear to be in conflict with that of a previous study that showed that mild hyperthermia was induced after a single ICV injection of ONO-AE-248 in rats (Oka, 2004), in our experimental design, the temperature of the animals was strictly maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5°C. To further address the potential effect of ONO-AE-248 alone on temperature, we treated a separate cohort of animals that were allowed free movement at room temperature. Like the mice that underwent the MCAO, these mice showed no changes in temperature. Accordingly, we believe that our results are accurate, but may differ from the previous study, which used rats and a higher dose (20 nmol ICV) of ONO-AE-248.

Stimulation of EP3 receptors is known to affect the release of intracellular calcium reserves. The increase in intracellular calcium can activate many enzymes, such as phospholipase C, phospholipase A2, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Each of these enzymes can increase stroke injury, and their inhibition has been shown to confer protection (Lipton, 1999). Abnormal calcium accumulation is also reported to cause mitochondrial dysfunction (Atlante et al., 2001) by depolarizing mitochondrial membrane potential (Akerman, 1978; Loew et al., 1994) and reducing ATP synthesis, which is thought to be a primary cause of cell death (Schinder et al., 1996). Reduction in ATP synthesis caused by increases in calcium concentration can lead to enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species and eventually to neurotoxicity (Antonsson et al., 1997; Bauer et al., 1998; Green and Reed, 1998; Zamzami et al., 1995).

Cyclic AMP elicits a wide range of cellular functions; it is reported to be involved in neuronal survival, axonal regeneration, and enhancement of neurite outgrowth (Hansen et al., 2001; Kao et al., 2002; Rydel and Greene, 1988). Activation of the EP3 receptor has been shown to inhibit cAMP synthesis in murine platelets (Fabre et al., 2001). In our study, activation of EP3 receptor by ONO-AE-248 might have inhibited cAMP synthesis and subsequently might have blocked the related downstream signaling pathways, such as protein kinase A and extracellular signal-regulated kinase, which are involved in cell survival. It is likely that the inhibition of these pathways enhanced cerebral injury, though further work in warranted to better address the exact signaling pathway involved in the toxicity mediated through EP3 receptors.

It is of interest that pharmaceutical companies are also considering the use of EP3 antagonists for clinical use. For example, a selective and potent EP3 receptor antagonist, DG041 (deCode genetics, 2006), is undergoing Phase-IIa clinical trials for peripheral arterial disease, which is characterized early by symptoms of pain or fatigue in the legs and buttocks during activity. People suffering with this disease have a higher than normal risk of death from heart attack and stroke. Clinical trials showed that oral administration of DG041 was well-tolerated, with no serious drug-related adverse events noted. Such results provide promise that EP3 mimetic drugs could be developed for use in other disorders, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury and tested in pre-clinical models and clinical settings.

In conclusion, since activation of EP3 receptors in brain worsened stroke outcome and excitotoxic brain lesion, and deletion of the receptor improved the outcome after NMDA-induced excitotoxicity, we propose that deletion or pharmacologic blockade of this receptor might limit brain damage induced by pro-inflammatory COX metabolites and that these receptors could be used as therapeutic targets for the prevention or reduction of ischemia-reperfusion-associated brain injury.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants (NS046400, AG022971) and a postdoctoral fellowship (ASA) from the Mid-Atlantic American Heart and Stroke Association. We thank all members of the Doré lab for helpful discussions and Claire Levine for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CBF

cerebral blood flow, PG, prostaglandin

- MABP

mean arterial blood pressure

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- TTC

2,3,5-triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride

- ICV

intracerebroventricular

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad AS, Ahmad M, de Brum-Fernandes AJ, Doré S. Prostaglandin EP4 receptor agonist protects against acute neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 2005;1066:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad AS, Saleem S, Ahmad M, Doré S. Prostaglandin EP1 receptor contributes to excitotoxicity and focal ischemic brain damage. Toxicol Sci. 2006a;89:265–270. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad AS, Zhuang H, Echeverria V, Doré S. Stimulation of prostaglandin EP2 receptors prevents NMDA-induced excitotoxicity. J Neurotrauma. 2006b;23:1895–1903. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Saleem S, Zhuang H, Ahmad AS, Echeverria V, Sapirstein A, Doré S. 1-HydroxyPGE1 reduces infarction volume in mouse transient cerebral ischemia. Eur J Neurosci. 2006c;23:35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman KE. Changes in membrane potential during calcium ion influx and efflux across the mitochondrial membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;502:359–366. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(78)90056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Brain Atlas [Internet] Allen Institute for Brain Science; Seattle (WA): 2004. –cited November 16, 2006. Available from: http://www.brain-map.org. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta A, Montessuit S, Lewis S, Martinou I, Bernasconi L, Bernard A, Mermod JJ, Mazzei G, Maundrell K, Gambale F, Sadoul R, Martinou JC. Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science. 1997;277:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlante A, Calissano P, Bobba A, Giannattasio S, Marra E, Passarella S. Glutamate neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MK, Vogt M, Los M, Siegel J, Wesselborg S, Schulze-Osthoff K. Role of reactive oxygen intermediates in activation-induced CD95 (APO-1/Fas) ligand expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8048–8055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilson HA, Mitchell DL, Ashby B. Human prostaglandin EP3 receptor isoforms show different agonist-induced internalization patterns. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaco-Moraes Y, Aspey B, Harrison M, de Belleroche J. Cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA induction in focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:1366–1372. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCode genetics, I. DG041 for Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) deCODE genetics, Inc.; Reykjavik, Iceland: 2006. http://www.decode.com/Pipeline/Index.php#pad. [Google Scholar]

- Doré S, Otsuka T, Mito T, Sugo N, Hand T, Wu L, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Andreasson K. Neuronal overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 increases cerebral infarction. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:155–162. doi: 10.1002/ana.10612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria V, Clerman A, Doré S. Stimulation of PGE2 receptors EP2 and EP4 protects cultured neurons against oxidative stress and cell death following β-amyloid exposure. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2199–2206. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engblom D, Ek M, Ericsson-Dahlstrand A, Blomqvist A. EP3 and EP4 receptor mRNA expression in peptidergic cell groups of the rat parabrachial nucleus. Neuroscience. 2004;126:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre JE, Nguyen M, Athirakul K, Coggins K, McNeish JD, Austin S, Parise LK, FitzGerald GA, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Activation of the murine EP3 receptor for PGE2 inhibits cAMP production and promotes platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:603–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggel R, Hoffman S, Nusing R, Narumiya S, Uhlig S. Platelet-activating factor-induced pulmonary edema is partly mediated by prostaglandin E(2), E-prostanoid 3-receptors, and potassium channels. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:657–662. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200111-071OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MR, Zha XM, Bok J, Green SH. Multiple distinct signal pathways, including an autocrine neurotrophic mechanism, contribute to the survival-promoting effect of depolarization on spiral ganglion neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2256–2267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02256.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Upadhyay UM, Tamargo RJ. Inflammation in stroke and focal cerebral ischemia. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Niwa K, Nogawa S, Zhao X, Nagayama M, Araki E, Morham S, Ross ME. Reduced susceptibility to ischemic brain injury and N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated neurotoxicity in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1294–1299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie A, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Negishi M. Mouse prostaglandin E receptor EP3 subtype mediates calcium signals via Gi in cDNA-transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:303–309. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav V, Jabre A, Lin SZ, Lee TJ. EP1- and EP3-receptors mediate prostaglandin E2-induced constriction of porcine large cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1305–1316. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000139446.61789.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao HT, Song HJ, Porton B, Ming GL, Hoh J, Abraham M, Czernik AJ, Pieribone VA, Poo MM, Greengard P. A protein kinase A-dependent molecular switch in synapsins regulates neurite outgrowth. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nn840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Anrather J, Zhou P, Park L, Wang G, Frys KA, Kunz A, Cho S, Orio M, Iadecola C. Prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptors: downstream effectors of COX-2 neurotoxicity. Nat Med. 2006;12:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nm1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiriyama M, Ushikubi F, Kobayashi T, Hirata M, Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Ligand binding specificities of the eight types and subtypes of the mouse prostanoid receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:217–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew LM, Carrington W, Tuft RA, Fay FS. Physiological cytosolic Ca2+ transients evoke concurrent mitochondrial depolarizations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12579–12583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas SM, Rothwell NJ, Gibson RM. The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S232–240. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Meyer-Kirchrath J, Kaber G, Jacoby C, Flogel U, Schrader J, Ruther U, Schror K, Hohlfeld T. Cardiospecific overexpression of the prostaglandin EP3 receptor attenuates ischemia-induced myocardial injury. Circulation. 2005;112:400–406. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in inflammatory and degenerative brain diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:901–910. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morham SG, Langenbach R, Loftin CD, Tiano HF, Vouloumanos N, Jennette JC, Mahler JF, Kluckman KD, Ledford A, Lee CA, Smithies O. Prostaglandin synthase 2 gene disruption causes severe renal pathology in the mouse. Cell. 1995;83:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kaneko T, Yamashita Y, Hasegawa H, Katoh H, Negishi M. Immunohistochemical localization of prostaglandin EP3 receptor in the rat nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:543–569. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000612)421:4<543::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba T, Sugimoto Y, Negishi M, Irie A, Ushikubi F, Kakizuka A, Ito S, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S. Alternative splicing of C-terminal tail of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3 determines G-protein specificity. Nature. 1993;365:166–170. doi: 10.1038/365166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumiya S, FitzGerald GA. Genetic and pharmacological analysis of prostanoid receptor function. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:25–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI13455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norel X, de Montpreville V, Brink C. Vasoconstriction induced by activation of EP1 and EP3 receptors in human lung: effects of ONO-AE-248, ONO-DI-004, ONO-8711 or ONO-8713. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2004;74:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T. Prostaglandin E2 as a mediator of fever: the role of prostaglandin E (EP) receptors. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3046–3057. doi: 10.2741/1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas AM, Soriano MA, Rodriguez-Farre E, Ferrer I. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA and protein following transient focal ischemia in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1995;200:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12108-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydel RE, Greene LA. cAMP analogs promote survival and neurite outgrowth in cultures of rat sympathetic and sensory neurons independently of nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1257–1261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinder AF, Olson EC, Spitzer NC, Montal M. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in glutamate neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6125–6133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah ZA, Namiranian K, Klaus J, Kibler K, Doré S. Use of an optimized transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery protocol for the mouse stroke model. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;15:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawik H, Volk B, Fiebich B, Hull M. Microglial expression of prostaglandin EP3 receptor in excitotoxic lesions in the rat striatum. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Negishi M, Hayashi Y, Namba T, Honda A, Watabe A, Hirata M, Narumiya S, Ichikawa A. Two isoforms of the EP3 receptor with different carboxyl-terminal domains. Identical ligand binding properties and different coupling properties with Gi proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2712–2718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzawa T, Miyaura C, Inada M, Maruyama T, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S, Suda T. The role of prostaglandin E receptor subtypes (EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4) in bone resorption: an analysis using specific agonists for the respective EPs. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1554–1559. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomimoto H, Shibata M, Ihara M, Akiguchi I, Ohtani R, Budka H. A comparative study on the expression of cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase during cerebral ischemia in humans. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2002;104:601–607. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldner C, Heise G, Schror K, Heering P. COX-2 inhibition and prostaglandin receptors in experimental nephritis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:969–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Endo T, Kitajima Y, Manase K, Nagasawa K, Honnma H, Hayashi T, Kudo R, Saito T. Elevation of both cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E(2) receptor EP3 expressions in rat placenta after uterine artery ischemia-reperfusion. Placenta. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhki K, Ueno A, Naraba H, Kojima F, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S, Oh-ishi S. Prostaglandin receptors EP2, EP3, and IP mediate exudate formation in carrageenin-induced mouse pleurisy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1218–1224. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharowski K, Olbrich A, Piper J, Hafner G, Kondo K, Thiemermann C. Selective activation of the prostanoid EP(3) receptor reduces myocardial infarct size in rodents. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2141–2147. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami N, Marchetti P, Castedo M, Decaudin D, Macho A, Hirsch T, Susin SA, Petit PX, Mignotte B, Kroemer G. Sequential reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and generation of reactive oxygen species in early programmed cell death. J Exp Med. 1995;182:367–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]