Abstract

This case report presents an incidental finding of a rectal GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) presenting as a submucosal calculus, not previously reported. A 53-year-old man without a significant medical history presented with abdominal pain in the left lower quadrant, and with constipation. Upon rectal examination, a hard submucosal swelling was palpated 4 cm from the anus, at 3 o’clock, in the left rectum wall. X-ray photos, computerized tomography (CT)-scan and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan clearly showed a calculus. Excision revealed a turnip-like lesion, 3.1×2.3×1.8 cm. Analysis showed it was a rectal GIST, a rare mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract, which expressed CD117 (or c-kit, a marker of kit-receptor tyrosine kinase) and CD34. Calcification is not a usual clinicopathological feature of GISTs [1–3], and although a number of rectal GISTs have been reported [4–9], we have found no cases so far of rectal GIST presenting as a submucosal calculus.

In general, GISTs are rare mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract (nerve tissue, smooth muscle). Histology and immunohistochemistry discriminate gastrointestinal stromal tumors from leiomyomas and neurinomas. The most important location is the stomach; the rectal location is rare. Usually, the classic signs of malignancy such as cellular invasion and metastasis are missing. A set of histologic criteria stratifies GIST for risk of malignant behavior such as mitotic activity and tumor size, cellular pleomorphism, developmental stage of the cell and quantity of cytoplasma [7,13]. Tumors with a high mitotic activity and size above 5 cm are considered malignant. Recent pharmacological advances such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors have determined c-kit (i.e., CD117) as the most important marker, amongst others. C-kit positive tumors respond extremely well to chemotherapy with Imatinib (Glivec®, Gleevec®) [10–12].

Keywords: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, Rectal tumor, Calculus

Case Report

A 53-year-old man without significant medical history presented with abdominal pain in the left lower quadrant and constipation. He got up that morning with a cramping abdominal ache that lasted over the day. He was nauseous, had vomited once, and ructus was present. There had been a small amount of hard stool and discomfort during defecation initially, but after the general practitioner had administered laxatives, he had liquid diarrhea. There was no complaint of constipation on a regular basis; this was a new finding. Tenesmus was absent. There was no bleeding or mucous discharge. He was feverish, with a temperature of 38.2°C. On examination, the abdomen was slightly distended. Auscultation showed diminished intestinal peristalsis, without borborygmi, and percussion was tympanic. Upon palpation, the abdomen was supple: there was no reflex rigidity nor guarding, and no rebound tenderness. Upon rectal examination, a hard submucosal swelling was palpated 4 cm from the anus, at 3 o’clock, in the left rectum wall. At the time, this was considered an accidental finding that was to be investigated later.

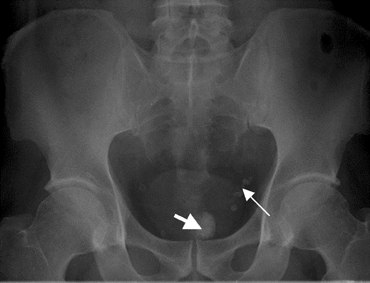

There were no specific deviations in the lab results. Ultrasound investigation displayed some hydronephrosis of the left kidney and a stone (size: 0.13×0.7 cm) of the left ureter. X-ray photos displayed a spherical lesion, projecting in the pelvis and situated in the rectum, and some phleboliths projecting on the left colon, but not the ureter stone (Fig. 1). Proctoscopy was not conclusive, so further investigation was performed. A computerized tomography (CT) scan and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan also clearly showed the submucosal calculus (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

X-ray photo showing the rectal calculus projecting in the pelvis (thick arrow) above the pubic symphysis and the phleboliths projecting on the left colon (thin arrow)

Fig. 2.

Computerized tomography (CT) scan showing the rectal calculus in the center (arrow)

Fig. 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The arrow shows the rectal calculus in the rectum wall

Our patient was diagnosed with abdominal pain and constipation based on a ureter stone and slight hydronephrosis of the left kidney, with coincidental finding of a rectal tumor. He was sent home with adequate analgesia and spontaneously released the ureter stone. An appointment was made for elective excision of the rectal calculus. Transanal excision was performed in the operating room (Fig. 4) and revealed a turnip-like lesion, dimensions 3.1×2.3×1.8 cm (Fig. 5). No normal tissue margins were excised because the tumor was not connected to the surrounding tissues. After surgery, the patient went home and recovered well, without any further complaints or complications.

Fig. 4.

Excision of the rectal calculus in the operating room

Fig. 5.

Excision revealed a turnip-like lesion, dimensions 3.1× 2.3×1.8 cm

The calculus was analyzed and consisted of fibroid and bony tissue, together with bundles of spindle-shaped cells with cigar-like nuclei. A partially calcified leiomyoma was considered at first, but supplementary immunoperoxidase analysis showed that the spindle-shaped cells were positive for CD117 (c-kit) and CD34. Unfortunately, histopathologic slides showing CD117 staining are not available to us. There was some focally positive smooth muscle actin, and MIB1 expression appeared negative. The mitotic count was low: fewer than five mitoses per 50 HPF. Only then did this analysis lead to the conclusion of rectal GIST, with extended calcification and ossification. It was classified as low-risk GIST because of the size (between 2 and 5 cm) and low mitotic count (Table 1).

Table I.

Prognosis of primary GIST

| Risk | Size (cm) | Mitotic count (per 50 HPF) |

|---|---|---|

| Very low risk | <2 | <5 |

| Low risk | 2–5 | <5 |

| Intermediate risk | <5 | 6–10 |

| 5–10 | <5 | |

| High risk | >5 | >5 |

| >10 | >Any mitotic rate | |

| Any tumor | >10 |

Note. from Fletcher et al (13). Abbreviations: HPF, high-power field.

Conclusion

Calcification is not a usual clinicopathologic feature of GISTs [1–3], and although a number of rectal GISTs have been reported, we have found no cases so far of rectal GIST presenting as a submucosal calculus. Furthermore, in the literature we found no cases of calcified GIST in other sites of the body. Expression of CD117 (c-kit) and CD34 proved that our calculus was in fact a rectal GIST. Calcification might be explained by internal bleeding of the tumor. The abdominal pain of our patient could be explained entirely by the ureteral stone. The rectal tumor might only explain the constipation. Because of the unpredictable biological behavior of gastrointestinal stromal tumors, the prognosis for our patient is uncertain, in spite of the low-risk character. For this reason, at multidisciplinary oncological deliberation, an expectant policy with regular follow-up was arranged.

References

- 1.Kim C, Day S, Yeh K (2001) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: analysis of clinical and pathologic factors. Am Surg 67(2):135–137 [PubMed]

- 2.Corless C, Fletcher J, Heinrich M (2004) Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol 22(18):3813–3825 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lau S, Tam K, Kam C, Lui C, Siu C, Lam H, Mak K (2004) Imaging of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Clin Radiol 59(6):487–498 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Yamaguchi M, Miyaki M, Iijima T, Matsumoto T, Kuzume M, Matsumiya A, Endo Y, Sanada Y, Kumada K (2000) Specific mutation in exon 11 of c-kit proto-oncogene in a malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum. J Gastroenterol xx(10):779–783 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hama Y, Okizuka H, Odajima K, Hayakawa M, Kusano S (2001) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum. Eur Radiol 2 2(2):216–219 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Shibata Y, Ueda T, Seki H, Yagihashi N (2001) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum. Eur J Gastrointest Hepatol 13(3):283–286 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Miettinen M, Furlong M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Burke A, Sobin L, Lasota J (2001) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas in the rectum and anus: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 144 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 25(9):1121–1133 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Nakayama T, Hirose H, Isobe K, Shiraishi K, Nishiumi T, Mori S, Furuta Y, Kasahara M (2003) Gastrointestinal tumor of the rectal mesentery. J Gastroenterol 38(2):186–189 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nasu K, Ueda T, Kai S, Anai H, Kimura Y, Yokoyama S, Miyakawa I (2004) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the rectovaginal septum. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 14(2):373–377 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn P, van der Graaf W, Verweij J (2003) Imatinib, a specific tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with a gastrointestinal stroma cell tumor. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 147(42):2051–2055 [PubMed]

- 11.de Silva C, Reid R (2003) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): C-kit mutations, CD117 expression, differential diagnosis and targeted cancer therapy with Imatinib. Pathol Oncol Res 9(1):13–19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Verweij J, Casali P, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay J, Issels R, van Oosterom A, Hogendoorn P, Van Glabbeke M, Bertulli R, Judson I (2004) Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumors with high-dose imatinib: randomized trial. Lancet 364(9440):1127–1134 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Fletcher C, Berman J, Corless C, et al. (2002) Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Reprinted from Human, Pathology, Vol. 33, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed]