Abstract

Background

In fair-skinned Caucasian populations both the incidence and mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma have been increasing over the past decades. With adjuvant therapies still being under investigation, early detection is the only way to improve melanoma patient survival. The influence of incisional biopsies on melanoma patient survival has been discussed for many years. This study investigates both the influence of diagnostic biopsy type and the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen on disease free and overall survival.

Methods

After (partial) removal of a pigmented skin lesion 471 patients were diagnosed with stage I/II melanoma and underwent re-excision and a sentinel node biopsy. All patients were followed prospectively, mean follow up >5 years. Patients were divided according to their diagnostic biopsy type (wide excision biopsy, narrow excision biopsy, excision biopsy with positive margins and incisional biopsy) and the presence of residual tumor cells in their re-excision specimen. Survival analysis was done using Cox’s proportional hazard model adjusted for eight important confounders of melanoma patient survival.

Results

The diagnostic biopsy was wide in 279 patients, narrow in 109 patients, 52 patients underwent an excision biopsy with positive margins and 31 patients an incisional biopsy. In 41 patients residual tumor cells were present in the re-excision specimen. Both the diagnostic biopsy type and the presence of tumor cells in the re-excision specimen did not influence disease free and overall survival of melanoma patients.

Conclusions

Non-radical diagnostic biopsies do not negatively influence melanoma patient survival.

Keywords: Melanoma, Survival, Diagnostic, Initial, Re-excision and Biopsy

In fair-skinned Caucasian populations cutaneous melanoma is an important growing public health problem, causing a heavy burden on healthcare services. Both its incidence and mortality rates have been increasing in Europe over the past decades.1 The absolute total number of new cases of melanoma in the Netherlands is expected to be more than 4800 in 2015, compared with around 2400 in 2000.2 The Netherlands, as many other countries, has a two-tiered medical care system in which patients need to seek a medical opinion initially from a general practitioner (GP) before referral if necessary, to a specialist.

The mean number needed to treat (NNT), defined as the mean number of pigmented lesions needed to be excised to identify one melanoma, among 468 GPs in Perth, Australia, was 29 and ranged from 83 in the youngest patients (≤19 years) to 11 in the oldest patients (≥70 years).3 Assuming that for each new case of melanoma another 20–50 patients with pigmented skin lesions will visit the GP, the demand for detection will increase quite markedly. With adjuvant therapies still being under investigation, early detection is the only way to improve melanoma patient survival.4 Dutch guidelines recommend pigmented skin lesions suspect for melanoma to be removed through a diagnostic excision biopsy with a minimal lateral clearance of 2 mm.5 This recommendation is inline with the advice of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to remove any suspicious lesion through excisional biopsy with a narrow margin of normal-appearing skin.6 The influence of an incisional biopsy on melanoma patient survival has been discussed for many years and different investigators have found contradicting results.7–15 Two recent publications concluding incisional biopsies not to interfere with melanoma patient survival were not able to end this discussion since patient groups were not fully comparable16 or follow up (FU) was short.17

This study investigated both the influence of diagnostic biopsy type and the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen on melanoma patient disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), in 471 patients with a mean FU of more than 5 years. Survival analysis was done using Cox’s proportional hazard model adjusted for; gender, age, site of primary melanoma, Breslow thickness, type of melanoma, ulceration, lymphatic invasion and sentinel node (SN) status. Both the diagnostic biopsy type and the presence of tumor cells in the re-excision specimen were found not to influence melanoma patient survival.

METHODS

Patients

Between August 1993 and September 2004, 551 patients were diagnosed with clinical stage I/II cutaneous melanoma according to criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and underwent re-excision of the primary melanoma site and a SN biopsy. If patients were referred to us from another institution the pathologic characteristics of the primary melanoma were reviewed in our hospital before the SN procedure. All patients were treated according to the same protocol; re-excision margins were 1 cm for melanomas with a Breslow thickness of ≤ 2 mm and 2 cm for melanomas with a Breslow thickness of >2 mm. To identify and retrieve the SN, the triple technique was used as described previously.18–20 In short, the day before surgery patients underwent a dynamic and static lymphoscintigraphy to determine the lymphatic drainage pattern. Just prior to surgery, Patent Blue V (Laboratoire Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) was injected intradermally next to the initial site of the melanoma. During surgery, guided by a hand held gamma probe and the blue staining of the draining tissues, the SN was removed.

To investigate the influence on survival, patients were divided both according to their diagnostic biopsy type; wide excisional biopsy (lateral clearance ≥ 2 mm), narrow excisional biopsy (lateral clearance < 2 mm), excisional biopsy with positive margins and incisional biopsy (includes punch) and the presence of residual tumor cells in their re-excision specimen.

Statistical Analysis

Data were processed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software for Windows 2000 (SPSS 11.5, Chicago, IL). Cox’s proportional hazard model was used for survival analysis. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Population

Between August 1993 and September 2004, 551 patients were diagnosed with clinical stage I/II cutaneous melanoma, 257 male (46.6%) and 294 female (53.4%) with a mean age of 49.9 years (Table 1). Most primary melanomas were located on the trunk (43.7%) or on the lower extremities (36.7%). Breslow thickness was categorized into four groups ( ≤ 1.00 mm; 1.01–2.00 mm; 2.01–4.00 mm; >4.01 mm), but due to spontaneous regression of the primary lesion remained unknown in 38 patients. The majority of patients had a superficial spreading melanoma (65.0%) or a nodular melanoma (26.7%). In 46 patients the type of melanoma was different or remained unknown (8.3%). Ulceration, defined as the absence of intact epidermis overlying the major portion of primary melanoma, was diagnosed in 80 patients (14.5%), unknown in 1 patient (0.2%) and absent in 470 patients (85.3%). Lymphatic invasion was present in 25 patients (4.5%), absent in 521 patients (94.6%) and remained unknown in 5 patients (0.9%). The SN was negative in 446 patients (80.9%) and positive in 94 patients (17.1%). In 11 patients the SN was not removed and the SN status remained unknown (2.0%). In total, there were 101 missing variables in 80 patients; all were excluded from the study.

SN Identification

In 11 of the 551 patients the SN status remained unknown (2.0%), in 5 of these patients the SN was located in the deep lobe of the parotid gland and in one patient the SN was located high in the left axilla, in all cases the decision was made not to remove the SN to avoid potential morbidity associated with the intervention. The SN was not identified in 3 cases due to non-visualization by preoperative lymphoscintigraphy. In one patient the SN was located in the right axilla and could not be removed because the patient was suffering from frozen shoulder syndrome, the physical condition of another patient did not allow further treatment. Therefore, the success rate of SN identification was 98% (540 of 551 patients). Two of the patients with the SN located in the deep lobe of the parotid gland experienced metastasis of the parotid gland, one patient is still alive with disease and one patient is dead of disease. The patient whose physical condition did not allow further treatment, passed away soon after re-excision of the primary melanoma site, from massive hematogenic and lymphogenic metastasis. The 8 remaining patients have shown no evidence of disease.

Diagnostic Biopsy Type and Survival

The influence of diagnostic biopsy type on DFS and OS was tested in 471 patients with a mean FU of more than 5 years; 279 patients (59.3%) underwent a wide excision biopsy, 109 patients (23.1%) a narrow excision biopsy, 52 patients (11.0%) an excision biopsy with positive margins and 31 patients (6.6%) an incision biopsy (Table 2A).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 551) |

|---|---|

| Follow up (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 257 (46.6%) |

| Female | 294 (53.4%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.9 (15.3) |

| Site of primary melanoma | |

| Lower extremity | 202 (36.7%) |

| Upper extremity | 63 (11.4%) |

| Head/Neck | 45 (8.2%) |

| Trunk | 241 (43.7%) |

| Breslow thickness (mm) | |

| 0 < x ≤ 1 | 153 (27.8%) |

| 1 < x ≤ 2 | 207 (37.6%) |

| 2 < x ≤ 4 | 114 (20.7%) |

| > 4 | 39 (7.1%) |

| Unknown (regression) | 38 (6.9%) |

| Type of melanoma | |

| Superficial spreading | 358 (65.0%) |

| Nodular | 147 (26.7%) |

| Other/Unknown | 46 (8.3%) |

| Ulceration | |

| No | 470 (85.3%) |

| Yes | 80 (14.5%) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2%) |

| Lymphatic invasion | |

| No | 521 (94.6%) |

| Yes | 25 (4.5%) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.9%) |

| Sentinel node status | |

| Negative | 446 (80.9%) |

| Positive | 94 (17.1%) |

| Unknown | 11 (2.0%) |

TABLE 2.

Patient distribution according to (A) diagnostic biopsy type and (B) the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen

| A | Patients (n = 471) | Follow up (years; mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic biopsy type | ||

| Wide excision biopsy ( ≥ 2 mm) | 279 (59.3%) | 5.0 ± 3.0 |

| Narrow excision biopsy (0<x<2 mm) | 109 (23.1%) | 6.0 ± 2.7 |

| Excision biopsy with positive margins | 52 (11.0%) | 5.8 ± 2.9 |

| Incision biopsy | 31 (6.6%) | 5.4 ± 2.4 |

| B | Patients (n = 441) | Follow up (years; mean ± SD) |

| Re excision specimen | ||

| No residual tumor cells | 400 (90.7%) | 5.1 ± 2.9 |

| Residual tumor cells | 41 (9.3%) | 5.8 ± 2.6 |

In 91/471 patients (19.3%) the SN was positive, 58/279 patients (20.8%) after a wide excision biopsy, 14/109 patients (12.8%) after a narrow excision biopsy, 15/52 patients (28.8%) after an excision biopsy with positive margins and 4/31 patients (12.9%) after an incisional biopsy.

In 79/471 patients (16.8%) a recurrence was found during FU, 45/279 patients (16.1%) after a wide excision biopsy (21 locoregional skin, 8 SN basin and 16 systemic), 17/109 patients (15.5%) after a narrow excision biopsy (7 locoregional skin, 2 SN basin and 8 systemic), 10/52 patients (19.2%) after an excision biopsy with positive margins (5 locoregional skin, 2 SN basin and 3 systemic) and 7/31 patients (22.6%) after an incision biopsy (5 locoregional skin, and 2 systemic). But confounding factors were not equally distributed between the diagnostic biopsy groups. Therefore, survival analysis was done using Cox’s proportional hazard model adjusted for; gender, age, site of primary melanoma, Breslow thickness, type of melanoma, ulceration, lymphatic invasion and sentinel node (SN) status.

In univariate analysis; gender, age, Breslow thickness, type of melanoma, ulceration, lymphatic invasion and SN status were all significantly related to both DFS and OS (Table 3). Site of primary melanoma on the head/neck was in univariate analysis only significantly related to DFS (Table 3). Diagnostic biopsy type did not have a significant relation with either DFS or OS (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of disease-free survival and overall survival according to diagnostic biopsy type

| Disease Free Survival | Overall Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Tested variables | P | HR | 95% CI | P | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| Diagnostic biopsy type | ||||||||

| Wide excision biopsy | 0.691 | 1.00 | – | 0.204 | 0.500 | 1.00 | – | 0.765 |

| Narrow excision biopsy | 0.360 | 0.71 | 0.39–1.28 | 0.255 | 0.315 | 0.74 | 0.37–1.51 | 0.411 |

| Excision biopsy with positive margins | 0.870 | 0.59 | 0.29–1.18 | 0.132 | 0.748 | 0.75 | 0.34–1.65 | 0.476 |

| Incision biopsy | 0.581 | 0.47 | 0.19–1.16 | 0.101 | 0.387 | 0.74 | 0.29–1.89 | 0.530 |

| Gender | 0.018 | 1.15 | 0.70–1.89 | 0.573 | 0.004 | 1.44 | 0.81–2.57 | 0.215 |

| Age (years) | 0.004 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.018 | 0.002 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.007 |

| Site of primary melanoma | ||||||||

| Lower extremity | 0.091 | 1.00 | – | 0.023 | 0.153 | |||

| Upper extremity | 0.825 | 0.91 | 0.41–2.01 | 0.809 | 0.071 | |||

| Head/Neck | 0.014 | 3.40 | 1.45–7.97 | 0.005 | 0.095 | |||

| Trunk | 0.731 | 0.93 | 0.54–1.61 | 0.790 | 0.063 | |||

| Breslow thickness (mm) | ||||||||

| 0 < x ≤ 1 | <0.001 | 1.00 | – | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.00 | – | 0.001 |

| 1 < x ≤ 2 | 0.003 | 13.19 | 1.77–98.41 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 8.15 | 1.07–62.19 | 0.043 |

| 2 < x ≤ 4 | <0.001 | 34.11 | 4.50–258.60 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 21.43 | 2.79–164.84 | 0.003 |

| > 4 | <0.001 | 15.73 | 1.86–132.81 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 11.85 | 1.35–103.70 | 0.025 |

| Type of melanoma | <0.001 | 1.58 | 0.95–2.62 | 0.078 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 0.88–2.79 | 0.128 |

| Ulceration | <0.001 | 1.83 | 1.09–3.07 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 0.89–3.04 | 0.116 |

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | 3.98 | 2.05–7.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2.19 | 1.07–4.48 | 0.032 |

| Sentinel node status | <0.001 | 3.87 | 2.23–6.70 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.19 | 1.75–5.81 | <0.001 |

Even though, diagnostic biopsy type did not have a significant relation with either DFS or OS in univariate Cox regression analysis it was also tested in multivariate Cox regression analysis together with all significant variables from univariate analysis, to investigate its influence on DFS and OS after correction for the confounding factors. In multivariate analysis, the only significant and independent predictors of both DFS and OS were; age, Breslow thickness, lymphatic invasion and SN status (Table 3). Site of primary melanoma on the lower extremities or head/neck and ulceration were in multivariate analysis only significant and independent predictors of DFS (Table 3). Also in multivariate analysis, diagnostic biopsy type did not have a significant relation with either DFS or OS (Fig. 1A, B).

FIG. 1.

A Disease free survival rates and B overall survival rates according to the initial biopsy type.

The same analysis was done after combining the groups; the wide excision biopsy group was joined with the narrow excision biopsy group and compared to the excision biopsy group with positive margins joined with the incision biopsy group. Still, diagnostic biopsy type did not have a significant influence on either DFS or OS (data not shown).

Residual Tumor Cells in the Re-Excision Specimen and Survival

441/471 Patients (93.6%) underwent re-excision of the primary melanoma site and in 30 patients (6.4%) the diagnostic biopsy was found to be sufficient. In 41/441 patients (9.3%) residual tumor cells were found in the re-excision specimen (Table 2B). All 41 patients with residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen underwent either an excision biopsy with positive margins or an incision biopsy. In none of the patients with a wide or narrow excision biopsy residual tumor cells were found.

In univariate analysis; gender, age, Breslow thickness, type of melanoma, ulceration, lymphatic invasion and SN status were all significantly related to both DFS and OS (Table 4). Site of primary melanoma on the lower extremity or head/neck was in univariate analysis significantly related to DFS and site of primary melanoma on the head/neck or trunk was significantly related to OS (Table 4). Residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen did not have a significant relation with either DFS or OS (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of disease-free survival and overall survival according to the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen

| Disease Free Survival | Overall Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Tested variables | P | HR | 95% CI | P | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| Residual tumor cells | 0.094 | 0.79 | 0.38–1.64 | 0.532 | 0.230 | 0.83 | 0.36–1.92 | 0.668 |

| Gender | 0.025 | 1.14 | 0.68–1.92 | 0.611 | 0.009 | 1.22 | 0.65–2.28 | 0.531 |

| Age (years) | 0.007 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.038 | 0.007 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.040 |

| Site of primary melanoma | ||||||||

| Lower extremity | 0.032 | 1.00 | – | 0.033 | 0.105 | 1.00 | – | 0.123 |

| Upper extremity | 0.830 | 0.95 | 0.41–2.20 | 0.910 | 0.069 | 2.21 | 0.85–5.71 | 0.102 |

| Head/Neck | 0.004 | 3.22 | 1.35–7.66 | 0.008 | 0.040 | 3.22 | 1.03–10.09 | 0.045 |

| Trunk | 0.647 | 0.96 | 0.54–1.74 | 0.903 | 0.049 | 2.02 | 0.98–4.20 | 0.059 |

| Breslow thickness (mm) | ||||||||

| 0 < x ≤ 1 | <0.001 | 1.00 | – | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.00 | – | 0.004 |

| 1 < x ≤ 2 | 0.005 | 12.82 | 1.71–96.07 | 0.013 | 0.020 | 7.99 | 1.04–61.49 | 0.046 |

| 2 < x ≤ 4 | <0.001 | 30.16 | 3.97–229.22 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 20.13 | 2.59–156.25 | 0.004 |

| > 4 | <0.001 | 15.91 | 1.86–136.25 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 11.84 | 1.32–106.54 | 0.028 |

| Type of melanoma | <0.001 | 1.61 | 0.95–2.73 | 0.076 | <0.001 | 1.63 | 0.87–3.04 | 0.128 |

| Ulceration | <0.001 | 1.55 | 0.90–2.67 | 0.119 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 0.85–3.05 | 0.141 |

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | 4.16 | 2.13–8.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2.24 | 1.04–4.80 | 0.038 |

| Sentinel node status | <0.001 | 3.30 | 1.87–5.83 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.05 | 1.56–5.96 | 0.001 |

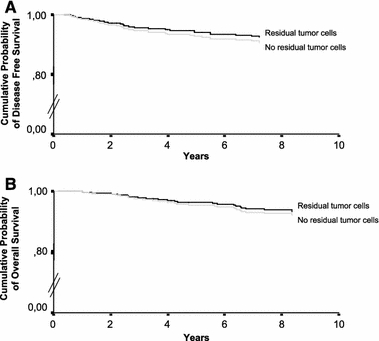

Even though, residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen did not have a significant relation with either DFS or OS in univariate Cox regression analysis it was also tested in multivariate Cox regression analysis together with all significant variables from univariate analysis, to investigate its influence on DFS and OS after correction for the confounding factors. In multivariate analysis, the only significant and independent predictors of both DFS and OS were; age, site of primary melanoma on the head/neck, Breslow thickness, lymphatic invasion and SN status (Table 4). Also in multivariate analysis, residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen did not have a significant relation with either DFS or OS (Fig. 2A, B).

FIG. 2.

A Disease free survival rates and B overall survival rates according to the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen.

Consistent Confounders of Melanoma Patient Survival

Age, Breslow thickness, lymphatic invasion and SN status were the most consistent, independent and significant confounders of melanoma patient DFS and OS (Table 3, 4). Site of the primary melanoma was not always an independent and significant confounder of melanoma patient survival, but location on the head/neck region consistently carried the highest hazard ratio (HR) (Table 3, 4). Surprisingly, ulceration was not an independent and significant confounder of OS (Table 3, 4).

DISCUSSION

Numerous investigators have studied the influence of incisional biopsy on melanoma patient survival and found contradicting results. Fitzpatrick et al. found a five-year OS rate of 30% in the incisional biopsy group as compared to 48% in the excisional biopsy group but the different biopsy groups were not matched for important prognostic factors.8 Epstein et al. found a more favorable ten-year OS in the biopsy group (65%) as compared to the primary wide excision group (56%) but biopsy was loosely defined as less than optimal or complete surgical excision.9 Ironside et al. found a five-year OS rate of 66% in the excision- and 43% in the incision biopsy group but failed to describe the distribution of prognostic factors between both groups.10 Rampen et al. also found a worse prognosis for patients after an incision biopsy (14 patients) but the study was small and retrospective.11 Griffiths et al. found no difference in survival but 7/19 incisional biopsy patients were excluded because of missing histopathological data.12 Survival rates were not significantly different between the incision- and excision biopsy groups of Lederman et al., but patient groups were matched for Breslow thickness only.13 Lees et al. also indicated no significant averse effect of incisional biopsy in 96 patients, but 40% of the histopathological data was not assessable.14 Austin et al did find a significantly reduced survival in the incisional biopsy group, but patients in the incisional biopsy group were also significantly older.15 The two most recent publications found no negative influence of incisional biopsies on melanoma patient survival but in Bong et al. patients groups were not fully matched and in Martin et al. median FU was only 28 months.16,17

This study not only investigated the influence of diagnostic biopsy type but also the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen on melanoma patient survival in patient groups adjusted for 8 important confounders of survival with a mean FU > 5 years. Excision biopsies with positive margins and incisional biopsies were found not to influence melanoma patient survival. Interestingly, DFS and OS even seemed slightly better in the non-radical biopsy groups (Fig. 1A, B). In line with this, patients with residual tumor cells in their re-excision specimen also had a slightly better survival as compared to patients without residual tumor cells in their re-excision specimen (Fig. 2A, B). Melanoma is the most immunogenic tumor identified to date; melanoma specific T cells are detectable both in the blood and in tumor draining lymph nodes from melanoma patients and their frequency can be increased by specific vaccination.21–23 This intrinsic immunogenicity makes melanoma lesions particularly amenable to therapeutic approaches aimed at strengthening tumor immune surveillance. Did residual tumor cells combined with biopsy induced wound healing trigger the melanoma patient’s immunesystem? In non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) biopsy induced tumor regression has previously been described, Swetter et al reported that 24% of NMSCs transected on the initial biopsy showed no residual tumor in the excision specimens and suggested biopsy induced wound healing to play an important role.24

Even though non-radical diagnostic biopsies and residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen do not have a negative influence on melanoma patient survival, the routine use of incision biopsies is not recommended. Incisional biopsies often consist only of a small percentage of the surface area of the pigmented skin lesion making it difficult to sample a representative area within the tumor. Somach et al found that 40% of the histopathological features were more pronounced in the re-excision specimen as compared to the incision biopsy and in 20% areas of invasive melanoma not detected in the incisional biopsy were observed in the re-excision specimen.25 Further more when melanoma is diagnosed, attempting to evaluate the depth of invasion in an incisional biopsy is treacherous and may lead to over- or underestimation of the invasion.26,27 Of course these problems are less prominent in excision biopsies with positive margins, here the majority of the lesion has been removed and only the outer borders are compromised making a sampling error highly unlikely.

In conclusion; age, Breslow thickness, lymphatic invasion and SN status were the most consistent, independent and significant confounders of melanoma patient DFS and OS. The site of primary melanoma and ulceration were also important confounders of survival. Both the diagnostic biopsy type and the presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen did not have a negative influence on melanoma patient DFS and OS. With melanoma incidence rates rising1 and early detection of melanoma still being the only way to improve melanoma patient survival,4 it is important for all physicians to feel confident about removing a pigmented skin lesion suspect for melanoma. Incisional biopsies are not recommended but there is no cause for concern when an excision biopsy turns out to have positive margins.

Footnotes

Barbara G. Molenkamp and Berbel J. R. Sluijter contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.de Vries E, Coebergh JW. Cutaneous malignant melanoma in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40:2355–66 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.de Vries E, van de Poll-Franse LV, Louwman WJ, de Gruijl FR, Coebergh JW. Predictions of skin cancer incidence in the Netherlands up to 2015. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152:481–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.English DR, Del Mar C, Burton RC. Factors influencing the number needed to excise: excision rates of pigmented lesions by general practitioners. Med J Aust 2004; 180:16–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.MacKie RM, Bray CA, Hole DJ, et al. Incidence of and survival from malignant melanoma in Scotland: an epidemiological study. Lancet 2002; 360:587–91 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Nederlandse Melanoom werkgroep. Richtlijn Melanoom van de huid, versie: 1.1. Alphen aan de Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications B.V., 2005

- 6.Diagnosis and treatment of early melanoma. NIH Consensus Development Conference. January 27–29, 1992. Consens Statement 1992; 10:1–25 [PubMed]

- 7.CADE S. Malignant melanoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1961; 28:331–66 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fitzpatrick PJ, Brown TC, Reid J. Malignant melanoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathological study. Can J Surg 1972; 15:90–101 [PubMed]

- 9.Epstein E, Bragg K, Linden G. Biopsy and prognosis of malignant melanoma. JAMA 1969; 208:1369–71 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ironside P, Pitt TT, Rank BK. Malignant melanoma: some aspects of pathology and prognosis. Aust N Z J Surg 1977; 47:70–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rampen FH, van Houten WA, Jop WC. Incisional procedures and prognosis in malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 1980; 5:313–20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Griffiths RW, Briggs JC. Biopsy procedures, primary wide excisional surgery and long term prognosis in primary clinical stage I invasive cutaneous malignant melanoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1985; 67:75–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Lederman JS, Sober AJ. Does biopsy type influence survival in clinical stage I cutaneous melanoma? J Am Acad Dermatol 1985; 13:983–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Lees VC, Briggs JC. Effect of initial biopsy procedure on prognosis in Stage 1 invasive cutaneous malignant melanoma: review of 1086 patients. Br J Surg 1991; 78:1108–10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Austin JR, Byers RM, Brown WD, Wolf P. Influence of biopsy on the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 1996; 18:107–17 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bong JL, Herd RM, Hunter JA. Incisional biopsy and melanoma prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:690–4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ross MI, Reintgen DS, Noyes RD, Edwards MJ, McMasters KM. Is incisional biopsy of melanoma harmful? Am J Surg 2005; 190:913–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Statius Muller MG, Borgstein PJ, Pijpers R, van Leeuwen PAM, van Diest PJ, Gupta A, Meijer S. Reliability of the sentinel node procedure in melanoma patients: analysis of failures after long-term follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol 2000; 7:461–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Statius Muller MG, van Leeuwen PAM, de Lange-De Klerk E.S., et al. The sentinel lymph node status is an important factor for predicting clinical outcome in patients with Stage I or II cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 2001; 91:2401–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Veen Hvd, Hoekstra OS, Paul MA, Cuesta MA, Meijer S. Gamma probe-guided sentinel node biopsy to select patients with melanoma for lymphadenectomy. Br J Surg 1994; 81:1769–70 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Banchereau J, Palucka AK, Dhodapkar M, et al. Immune and clinical responses in patients with metastatic melanoma to CD34(+) progenitor-derived dendritic cell vaccine. Cancer Res 2001; 61:6451–8 [PubMed]

- 22.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, et al. Determinant spreading associated with clinical response in dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9:998–1008 [PubMed]

- 23.Romero P, Dunbar PR, Valmori D, et al. Ex vivo staining of metastatic lymph nodes by class I major histocompatibility complex tetramers reveals high numbers of antigen- experienced tumor-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 1998; 188:1641–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Swetter SM, Boldrick JC, Pierre P, Wong P, Egbert BM. Effects of biopsy-induced wound healing on residual basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas: rate of tumor regression in excisional specimens. J Cutan Pathol 2003; 30:139–46 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Somach SC, Taira JW, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Pigmented lesions in actinically damaged skin. Histopathologic comparison of biopsy and excisional specimens. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132:1297–302 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Lorusso GD, Sarma DP, Sarwar SF. Punch biopsies of melanoma: A diagnostic peril. Dermatol Online J 2005; 11:7 [PubMed]

- 27.Karimipour DJ, Schwartz JL, Wang TS, et al. Microstaging accuracy after subtotal incisional biopsy of cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:798–802 [DOI] [PubMed]