Abstract

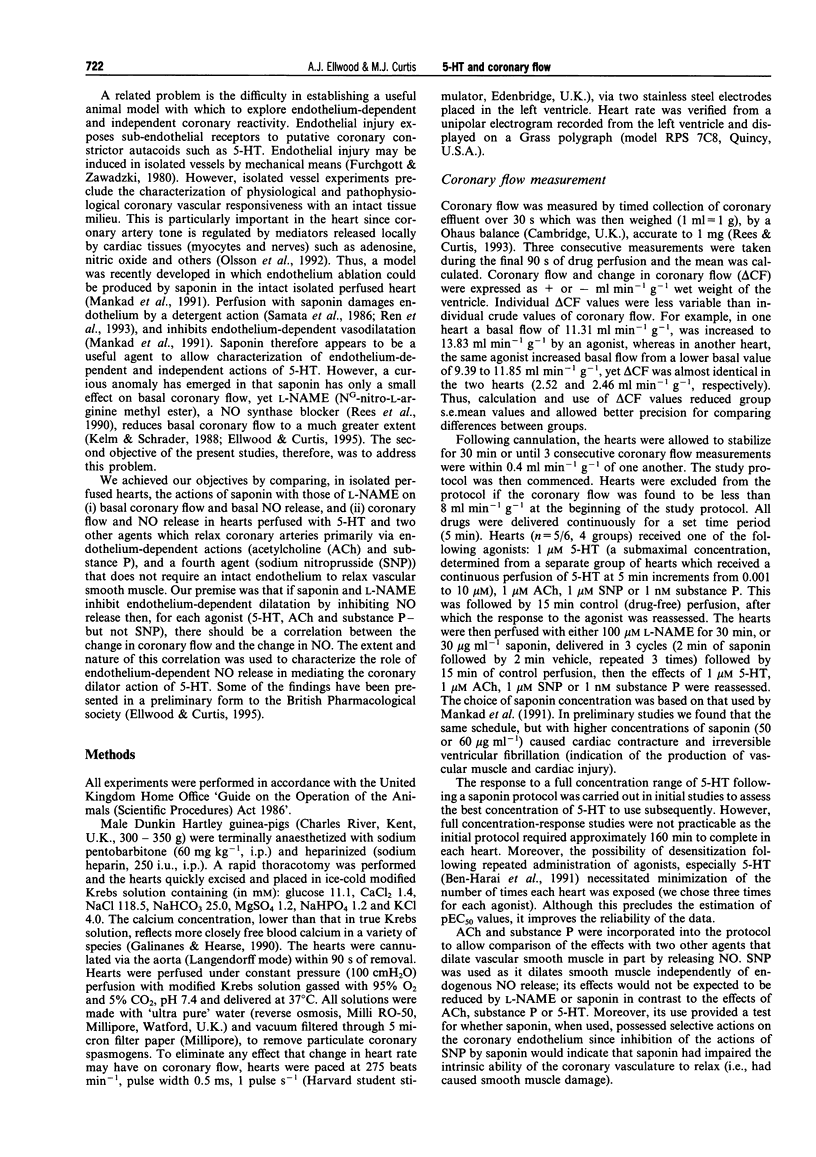

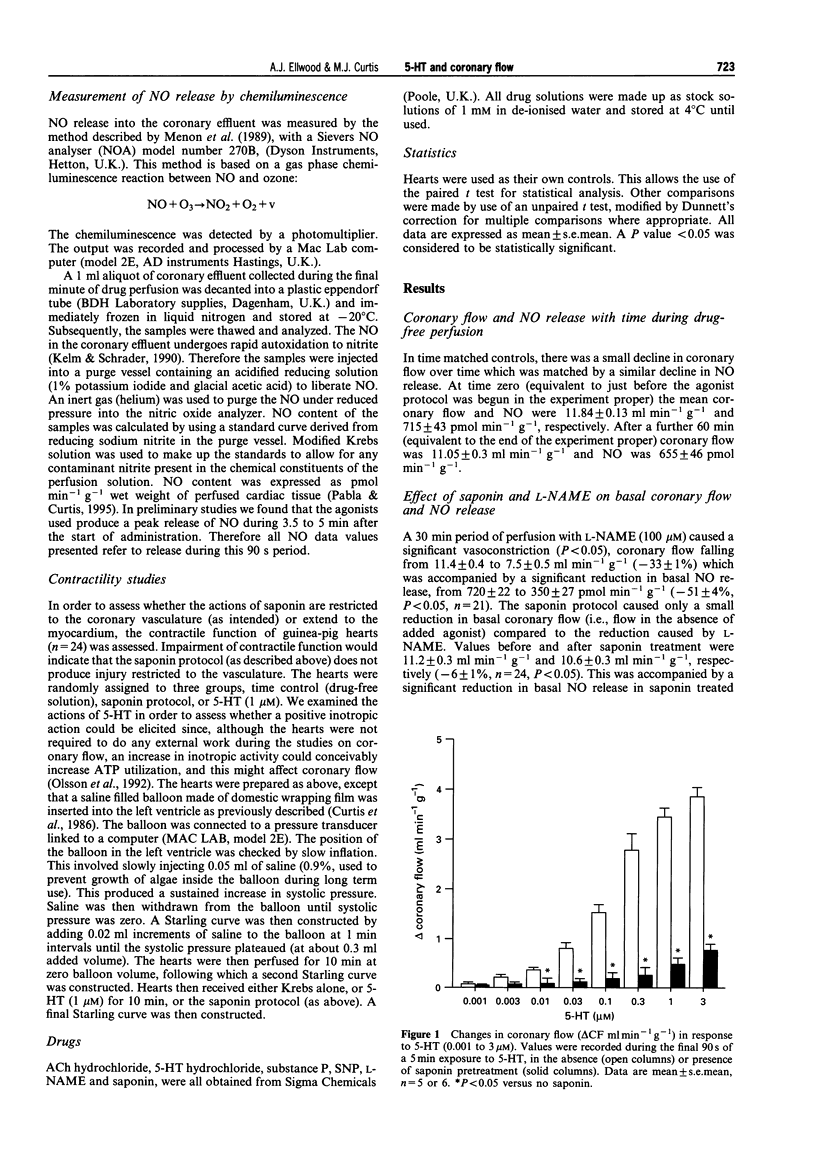

1. We assessed whether a submaximal concentration (1 microM) of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) releases nitric oxide (NO) from the coronary endothelium in guinea-pig perfused heart (n = 5 or 6/group) by direct detection of NO in coronary effluent, and determined whether this accounts for the associated coronary dilation. We also tested whether saponin is a selective and specific tool for examining the role of this mechanism in mediating agonist-induced coronary dilatation. 2. Continuous 5 min perfusion with 5-HT, or acetylcholine (ACh; 1 microM), substance P (1 nM) or sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 1 microM) increased coronary flow from baseline by 3.6 +/- 0.2, 3.4 +/- 0.2, 1.8 +/- 0.1 and 4.1 +/- 0.2 ml min-1 g-1, respectively (all P < 0.05). Coronary effluent NO content, detected by chemiluminescence, was correspondingly increased from baseline by 715 +/- 85, 920 +/- 136, 1019 +/- 58 and 2333 +/- 114 pmol min-1 g-1, respectively (all P < 0.05). 3. Continuous perfusion for 30 min with NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) 100 microM reduced basal coronary effluent NO content by 370 +/- 32 pmol min-1 g-1 and coronary flow by 7.5 +/- 0.5 ml min-1 g-1 (both P < 0.05). Saponin (three cycles of 2 min of 30 micrograms ml-1 saponin perfusion interrupted by 2 min control perfusion) reduced basal coronary NO content by a similar amount (307 +/- 22 pmol min-1 g-1) but reduced basal coronary flow by only 0.6 +/- 0.2 ml min-1 g-1 (P < 0.05 versus the effect of L-NAME). 4. The increases in coronary flow in response to (5-HT), ACh and substance P were reduced (all P < 0.05) by 100 microM L-NAME to 1.2 +/- 0.3, 1.2 +/- 0.4 and 0.3 +/- 0.3 ml min-1 g-1, respectively. However, the flow increase in response to SNP was not reduced; it was in fact increased slightly to 4.8 +/- 0.4 ml min-1 g-1 (P < 0.05). 5. Similarly, after treatment with saponin, the increases in coronary flow in response to 5-HT, ACh and substance P were reduced to 2.1 +/- 0.3, 1.3 +/- 0.3 and 0.4 +/- 0.2 ml min-1 g-1, respectively (all P < 0.05). Again, the response to SNP was increased slightly to 4.6 +/- 0.5 ml min-1 g-1 (P < 0.05). 6. L-NAME and saponin also inhibited 5-HT, ACh and substance P-induced NO release (P < 0.05), without affecting equivalent responses to SNP. 7. For substance P, the change in coronary flow (delta CF) correlated with log10 delta NO in the presence and absence of saponin and L-NAME; delta CF = 1.2(log delta NO) 1.9; r = 0.92; P < 0.05. For 5-HT the relationship was delta CF = 2.2(log delta NO-2.7; r = 0.79; P < 0.05, indicating that 5-HT causes a disproportionately greater increase in coronary flow per release of NO. This was taken to indicate that 5-HT relaxes coronary vasculature in part by releasing NO, but in part by additional mechanisms. ACh resembled 5-HT in this respect. 8. Saponin had no effect on cardiac systolic or diastolic contractile function assessed by the construction of Starling curves with an isochoric intraventricular balloon. 9. In conclusion, despite its minimal effect on basal coronary flow, saponin is an effective tool for revealing endothelium-dependent actions of coronary vasodilator substances and has selectivity in that it does not impair endothelium-independent vasodilatation or cardiac contractile function. 5-HT dilates guinea-pig coronary arteries largely by the release of NO from the coronary endothelium.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ben-Harari R. R., Dalton B. A., Osman R., Maayani S. Kinetic characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor desensitization in isolated guinea-pig trachea and rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991 Apr;257(1):416–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

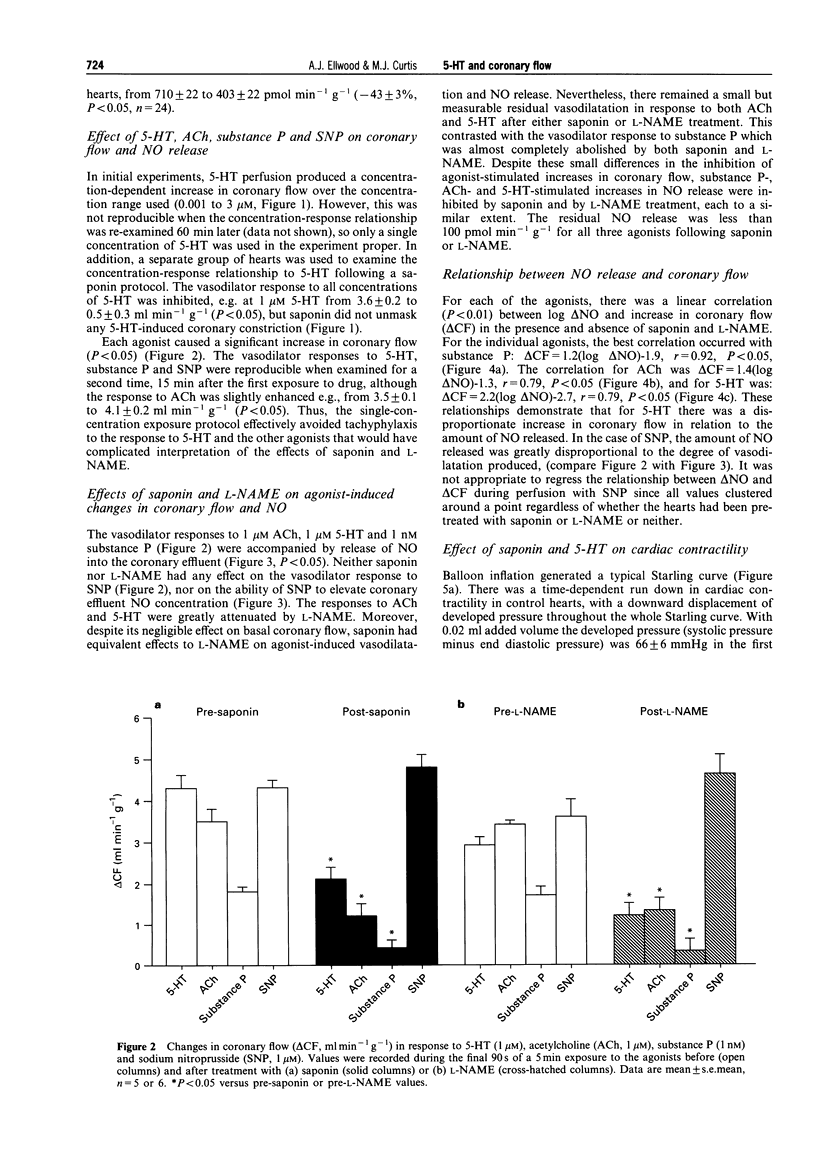

- Benyó Z., Kiss G., Szabó C., Csáki C., Kovách A. G. Importance of basal nitric oxide synthesis in regulation of myocardial blood flow. Cardiovasc Res. 1991 Aug;25(8):700–703. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

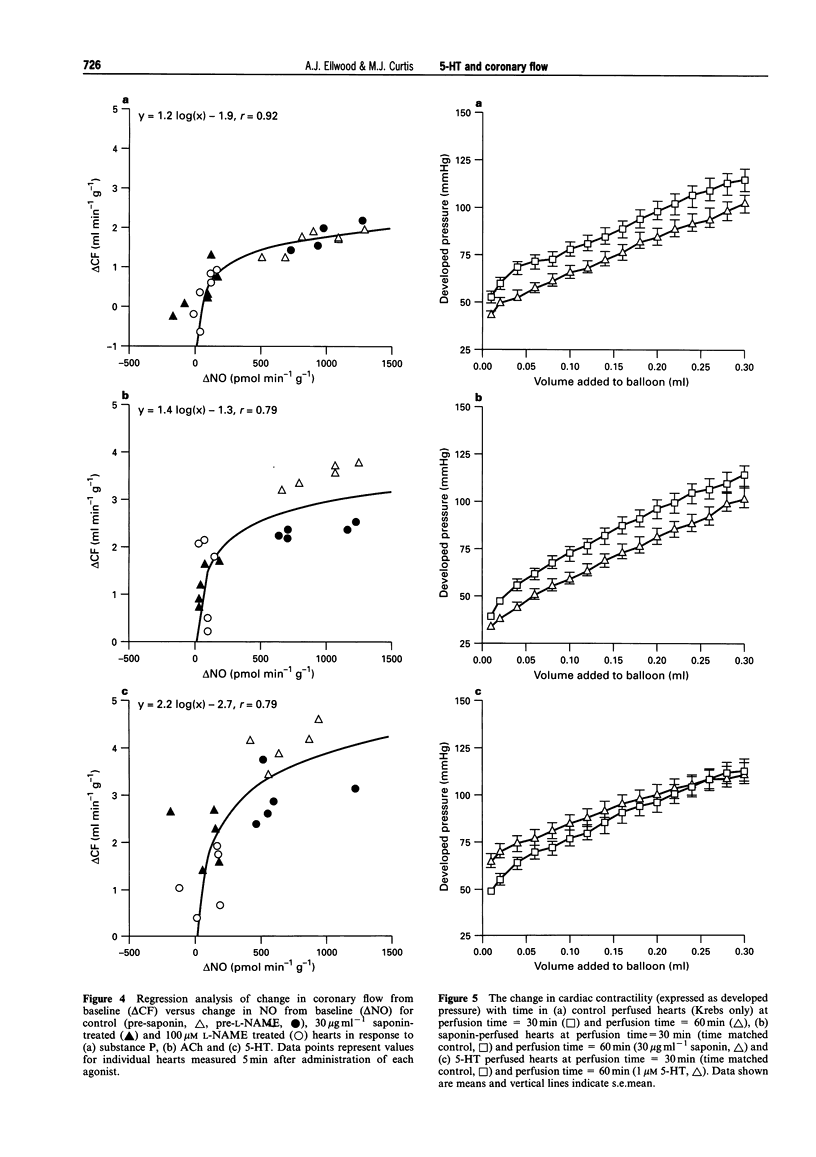

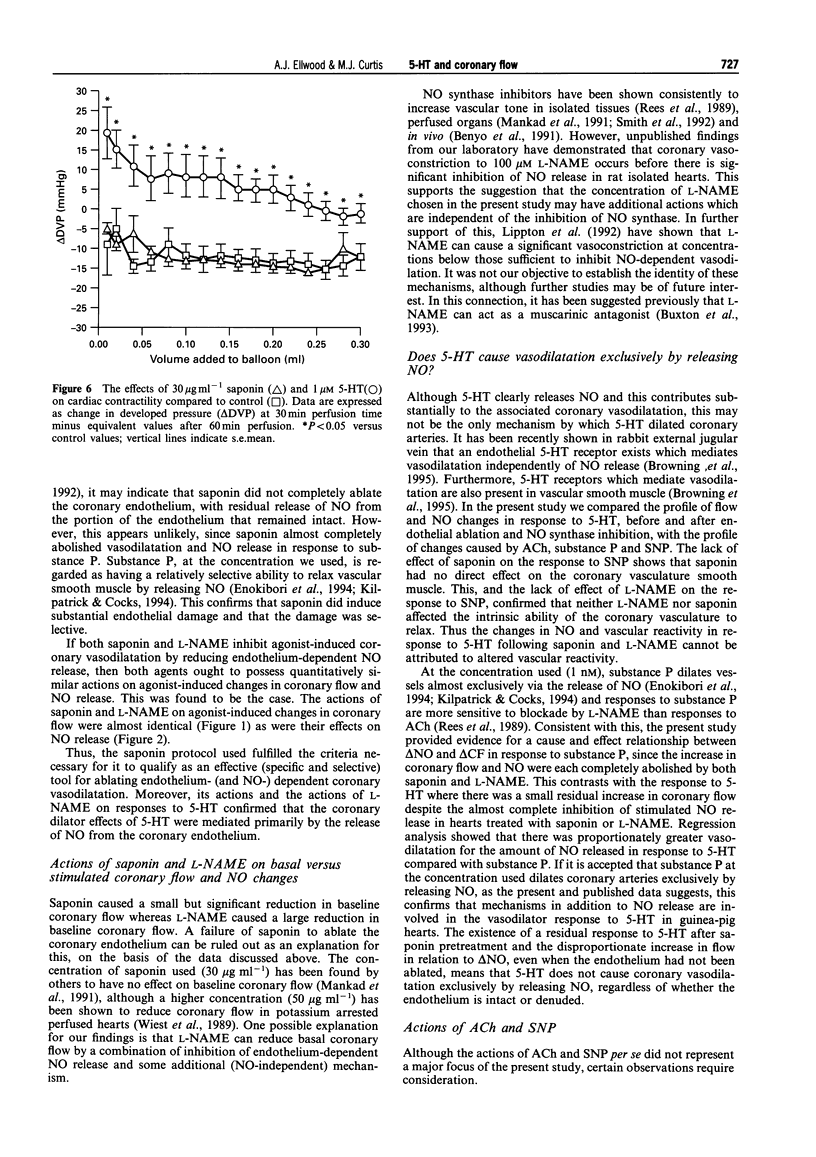

- Buxton I. L., Cheek D. J., Eckman D., Westfall D. P., Sanders K. M., Keef K. D. NG-nitro L-arginine methyl ester and other alkyl esters of arginine are muscarinic receptor antagonists. Circ Res. 1993 Feb;72(2):387–395. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. F., Cheung D. W. Characterization of acetylcholine-induced membrane hyperpolarization in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1992 Feb;70(2):257–263. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester A. H., Allen S. P., Tadjkarimi S., Yacoub M. H. Interaction between thromboxane A2 and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor subtypes in human coronary arteries. Circulation. 1993 Mar;87(3):874–880. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks T. M., Angus J. A. Endothelium-dependent relaxation of coronary arteries by noradrenaline and serotonin. Nature. 1983 Oct 13;305(5935):627–630. doi: 10.1038/305627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor H. E., Feniuk W., Humphrey P. P. 5-Hydroxytryptamine contracts human coronary arteries predominantly via 5-HT2 receptor activation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989 Feb 14;161(1):91–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M. J., Macleod B. A., Tabrizchi R., Walker M. J. An improved perfusion apparatus for small animal hearts. J Pharmacol Methods. 1986 Feb;15(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(86)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enokibori M., Okamura T., Toda N. Mechanism underlying substance P-induced relaxation in dog isolated superficial temporal arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 1994 Jan;111(1):77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott R. F. Role of endothelium in responses of vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 1983 Nov;53(5):557–573. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott R. F., Zawadzki J. V. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980 Nov 27;288(5789):373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiñanes M., Hearse D. J. Species differences in susceptibility to ischemic injury and responsiveness to myocardial protection. Cardioscience. 1990 Jun;1(2):127–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland C. J., McPherson G. A. Evidence that nitric oxide does not mediate the hyperpolarization and relaxation to acetylcholine in the rat small mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1992 Feb;105(2):429–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith T. M., Henderson A. H., Edwards D. H., Lewis M. J. Isolated perfused rabbit coronary artery and aortic strip preparations: the role of endothelium-derived relaxant factor. J Physiol. 1984 Jun;351:13–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro L. J., Byrns R. E., Buga G. M., Wood K. S. Mechanisms of endothelium-dependent vascular smooth muscle relaxation elicited by bradykinin and VIP. Am J Physiol. 1987 Nov;253(5 Pt 2):H1074–H1082. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann A. J., Parsons A. A., Brown A. M. Human arterial constrictor serotonin receptors. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Dec;27(12):2094–2103. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.12.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm M., Schrader J. Control of coronary vascular tone by nitric oxide. Circ Res. 1990 Jun;66(6):1561–1575. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm M., Schrader J. Nitric oxide release from the isolated guinea pig heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988 Oct 18;155(3):317–321. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90522-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick E. V., Cocks T. M. Evidence for differential roles of nitric oxide (NO) and hyperpolarization in endothelium-dependent relaxation of pig isolated coronary artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1994 Jun;112(2):557–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimaschewski L., Kummer W., Mayer B., Couraud J. Y., Preissler U., Philippin B., Heym C. Nitric oxide synthase in cardiac nerve fibers and neurons of rat and guinea pig heart. Circ Res. 1992 Dec;71(6):1533–1537. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.6.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaru T., Lamping K. G., Eastham C. L., Harrison D. G., Marcus M. L., Dellsperger K. C. Effect of an arginine analogue on acetylcholine-induced coronary microvascular dilatation in dogs. Am J Physiol. 1991 Dec;261(6 Pt 2):H2001–H2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefroy D. C., Crake T., Uren N. G., Davies G. J., Maseri A. Effect of inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis on epicardial coronary artery caliber and coronary blood flow in humans. Circulation. 1993 Jul;88(1):43–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippton H. L., Hao Q., Hyman A. L-NAME enhances pulmonary vasoconstriction without inhibiting EDRF-dependent vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1992 Dec;73(6):2432–2439. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.6.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankad P. S., Chester A. H., Yacoub M. H. 5-Hydroxytryptamine mediates endothelium dependent coronary vasodilatation in the isolated rat heart by the release of nitric oxide. Cardiovasc Res. 1991 Mar;25(3):244–248. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden E. P., Clarke J. G., Davies G. J., Kaski J. C., Haider A. W., Maseri A. Effect of intracoronary serotonin on coronary vessels in patients with stable angina and patients with variant angina. N Engl J Med. 1991 Mar 7;324(10):648–654. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103073241002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon N. K., Wolf A., Zehetgruber M., Bing R. J. An improved chemiluminescence assay suggests non nitric oxide-mediated action of lysophosphatidylcholine and acetylcholine. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1989 Jul;191(3):316–319. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-rc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S., Rees D. D., Schulz R., Palmer R. M. Development and mechanism of a specific supersensitivity to nitrovasodilators after inhibition of vascular nitric oxide synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Mar 15;88(6):2166–2170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabla R., Curtis M. J. Effects of NO modulation on cardiac arrhythmias in the rat isolated heart. Circ Res. 1995 Nov;77(5):984–992. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane F., Pearson T., Garland C. J. Multiple pathways underlying endothelium-dependent relaxation in the rabbit isolated femoral artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1995 May;115(1):31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D. D., Palmer R. M., Hodson H. F., Moncada S. A specific inhibitor of nitric oxide formation from L-arginine attenuates endothelium-dependent relaxation. Br J Pharmacol. 1989 Feb;96(2):418–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D. D., Palmer R. M., Schulz R., Hodson H. F., Moncada S. Characterization of three inhibitors of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1990 Nov;101(3):746–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S. A., Curtis M. J. Selective IK blockade as an antiarrhythmic mechanism: effects of UK66,914 on ischaemia and reperfusion arrhythmias in rat and rabbit hearts. Br J Pharmacol. 1993 Jan;108(1):139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L. M., Nakane T., Chiba S. Muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating vasodilation and vasoconstriction in isolated, perfused simian coronary arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993 Dec;22(6):841–846. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199312000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samata K., Kimura T., Satoh S., Watanabe H. Chemical removal of the endothelium by saponin in the isolated dog femoral artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986 Aug 22;128(1-2):85–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki Y., Su C. Endothelium removal augments vasodilation by sodium nitroprusside and sodium nitrite. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985 Aug 7;114(1):93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. E., Palmer R. M., Bucknall C. A., Moncada S. Role of nitric oxide synthesis in the regulation of coronary vascular tone in the isolated perfused rabbit heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1992 May;26(5):508–512. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tare M., Parkington H. C., Coleman H. A., Neild T. O., Dusting G. J. Hyperpolarization and relaxation of arterial smooth muscle caused by nitric oxide derived from the endothelium. Nature. 1990 Jul 5;346(6279):69–71. doi: 10.1038/346069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte P. M. Platelet-derived serotonin, the endothelium, and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991;17 (Suppl 5):S6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron G. J., Garland C. J. Contribution of both nitric oxide and a change in membrane potential to acetylcholine-induced relaxation in the rat small mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1994 Jul;112(3):831–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. E., Angus J. A. Acute and chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthase in conscious rabbits: role of nitric oxide in the control of vascular tone. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993 May;21(5):804–814. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199305000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiest E., Trach V., Dämmgen J. Removal of endothelial function in coronary resistance vessels by saponin. Basic Res Cardiol. 1989 Sep-Oct;84(5):469–478. doi: 10.1007/BF01908199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., Triggle C. R. Endothelium-independent relaxations to acetylcholine and A23187 in the human umbilical artery. J Vasc Res. 1994 Mar-Apr;31(2):92–105. doi: 10.1159/000159035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]